wire rope failure osha in stock

Scope. This section applies to slings used in conjunction with other material handling equipment for the movement of material by hoisting, in employments covered by this part. The types of slings covered are those made from alloy steel chain, wire rope, metal mesh, natural or synthetic fiber rope (conventional three strand construction), and synthetic web (nylon, polyester, and polypropylene).

Cable laid endless sling-mechanical joint is a wire rope sling made endless by joining the ends of a single length of cable laid rope with one or more metallic fittings.

Cable laid grommet-hand tucked is an endless wire rope sling made from one length of rope wrapped six times around a core formed by hand tucking the ends of the rope inside the six wraps.

Cable laid rope sling-mechanical joint is a wire rope sling made from a cable laid rope with eyes fabricated by pressing or swaging one or more metal sleeves over the rope junction.

Master link or gathering ring is a forged or welded steel link used to support all members (legs) of an alloy steel chain sling or wire rope sling. (See Fig. N-184-3.)

Diagram indicates Forms of Hitch and Kind of Sling. Eye&Eye Vertical Hitch. Eye&Eye Choker Hitch. Eye&Eye Basket Hitch (Alterates have identical load rations). Endless Vertical Hitch. Endless Choker Hitch. Endless Basket Hitch (Alternateve have identical load ratings). Notes: Angles 5 deg or less from the veritcal may be considered vertical angles. For slings with legs more than 5 deg off vertical, the actual angle as shown in Figure N-184-5 must be considered. Explanation of Symbols: Minimum Diameter of Curvature. Represents a contact surface which shall have a diameter of curvature at least double the diameter of the rope from which the sling is made. Represents a contact surface which shall have a diameter of curvature at least 8 times the diameter of the rope. Represents a load in a choker hitch and illustrates the rotary force on the load and/or the slippage of the rope in contact with the load. Diameter of curvature of load surface shall be at least double the diameter of the rope.

Strand laid endless sling-mechanical joint is a wire rope sling made endless from one length of rope with the ends joined by one or more metallic fittings.

Strand laid grommet-hand tucked is an endless wire rope sling made from one length of strand wrapped six times around a core formed by hand tucking the ends of the strand inside the six wraps.

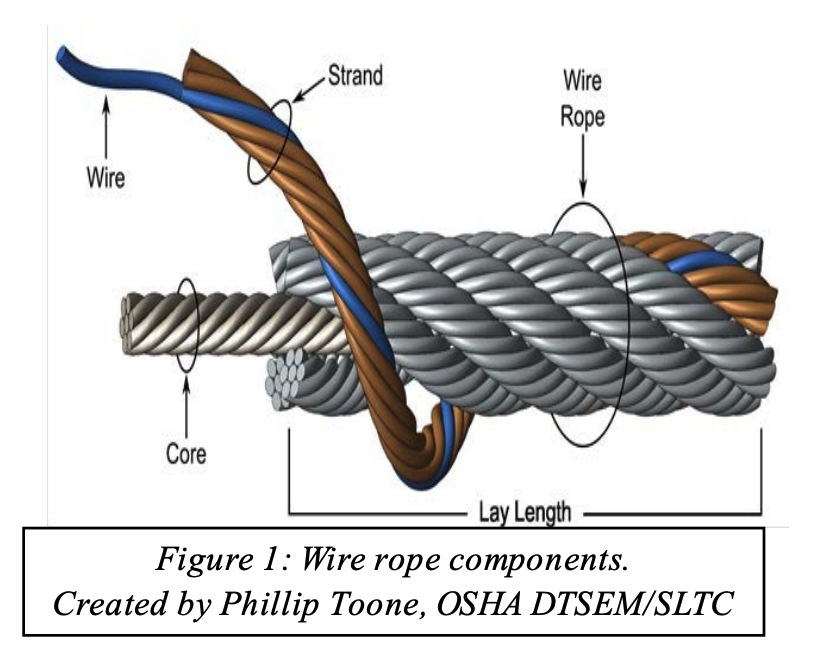

Strand laid rope is a wire rope made with strands (usually six or eight) wrapped around a fiber core, wire strand core, or independent wire rope core (IWRC).

Sling use. Employers must use only wire-rope slings that have permanently affixed and legible identification markings as prescribed by the manufacturer, and that indicate the recommended safe working load for the type(s) of hitch(es) used, the angle upon which it is based, and the number of legs if more than one.

Cable laid and 6 × 19 and 6 × 37 slings shall have a minimum clear length of wire rope 10 times the component rope diameter between splices, sleeves or end fittings.

Safe operating temperatures. Fiber core wire rope slings of all grades shall be permanently removed from service if they are exposed to temperatures in excess of 200 °F. When nonfiber core wire rope slings of any grade are used at temperatures above 400 °F or below minus 60 °F, recommendations of the sling manufacturer regarding use at that temperature shall be followed.

Sling use. Employers must use natural and synthetic fiber-rope slings that have permanently affixed and legible identification markings stating the rated capacity for the type(s) of hitch(es) used and the angle upon which it is based, type of fiber material, and the number of legs if more than one.

Safe operating temperatures. Natural and synthetic fiber rope slings, except for wet frozen slings, may be used in a temperature range from minus 20 °F to plus 180 °F without decreasing the working load limit. For operations outside this temperature range and for wet frozen slings, the sling manufacturer"s recommendations shall be followed.

Splicing. Spliced fiber rope slings shall not be used unless they have been spliced in accordance with the following minimum requirements and in accordance with any additional recommendations of the manufacturer:

In manila rope, eye splices shall consist of at least three full tucks, and short splices shall consist of at least six full tucks, three on each side of the splice center line.

In synthetic fiber rope, eye splices shall consist of at least four full tucks, and short splices shall consist of at least eight full tucks, four on each side of the center line.

Strand end tails shall not be trimmed flush with the surface of the rope immediately adjacent to the full tucks. This applies to all types of fiber rope and both eye and short splices. For fiber rope under one inch in diameter, the tail shall project at least six rope diameters beyond the last full tuck. For fiber rope one inch in diameter and larger, the tail shall project at least six inches beyond the last full tuck. Where a projecting tail interferes with the use of the sling, the tail shall be tapered and spliced into the body of the rope using at least two additional tucks (which will require a tail length of approximately six rope diameters beyond the last full tuck).

Removal from service. Natural and synthetic fiber rope slings shall be immediately removed from service if any of the following conditions are present:

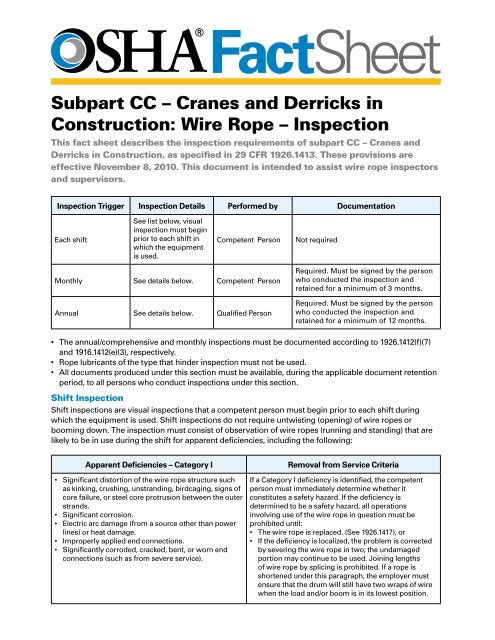

A competent person must begin a visual inspection prior to each shift the equipment is used, which must be completed before or during that shift. The inspection must consist of observation of wire ropes (running and standing) that are likely to be in use during the shift for apparent deficiencies, including those listed in paragraph (a)(2) of this section. Untwisting (opening) of wire rope or booming down is not required as part of this inspection.

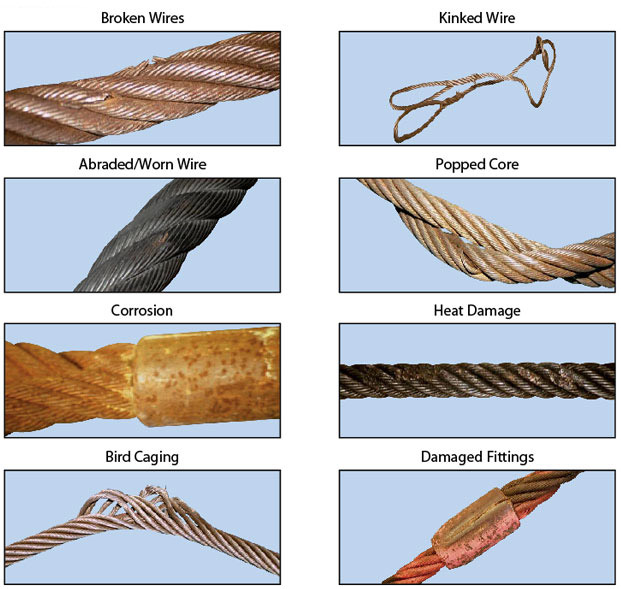

Significant distortion of the wire rope structure such as kinking, crushing, unstranding, birdcaging, signs of core failure or steel core protrusion between the outer strands.

In running wire ropes: Six randomly distributed broken wires in one rope lay or three broken wires in one strand in one rope lay, where a rope lay is the length along the rope in which one strand makes a complete revolution around the rope.

In rotation resistant ropes: Two randomly distributed broken wires in six rope diameters or four randomly distributed broken wires in 30 rope diameters.

In pendants or standing wire ropes: More than two broken wires in one rope lay located in rope beyond end connections and/or more than one broken wire in a rope lay located at an end connection.

If a deficiency in Category I (see paragraph (a)(2)(i) of this section) is identified, an immediate determination must be made by the competent person as to whether the deficiency constitutes a safety hazard. If the deficiency is determined to constitute a safety hazard, operations involving use of the wire rope in question must be prohibited until:

If the deficiency is localized, the problem is corrected by severing the wire rope in two; the undamaged portion may continue to be used. Joining lengths of wire rope by splicing is prohibited. If a rope is shortened under this paragraph, the employer must ensure that the drum will still have two wraps of wire when the load and/or boom is in its lowest position.

If a deficiency in Category II (see paragraph (a)(2)(ii) of this section) is identified, operations involving use of the wire rope in question must be prohibited until:

The employer complies with the wire rope manufacturer"s established criterion for removal from service or a different criterion that the wire rope manufacturer has approved in writing for that specific wire rope (see § 1926.1417),

If the deficiency is localized, the problem is corrected by severing the wire rope in two; the undamaged portion may continue to be used. Joining lengths of wire rope by splicing is prohibited. If a rope is shortened under this paragraph, the employer must ensure that the drum will still have two wraps of wire when the load and/or boom is in its lowest position.

If the deficiency (other than power line contact) is localized, the problem is corrected by severing the wire rope in two; the undamaged portion may continue to be used. Joining lengths of wire rope by splicing is prohibited. Repair of wire rope that contacted an energized power line is also prohibited. If a rope is shortened under this paragraph, the employer must ensure that the drum will still have two wraps of wire when the load and/or boom is in its lowest position.

Where a wire rope is required to be removed from service under this section, either the equipment (as a whole) or the hoist with that wire rope must be tagged-out, in accordance with § 1926.1417(f)(1), until the wire rope is repaired or replaced.

Wire ropes on equipment must not be used until an inspection under this paragraph demonstrates that no corrective action under paragraph (a)(4) of this section is required.

At least every 12 months, wire ropes in use on equipment must be inspected by a qualified person in accordance with paragraph (a) of this section (shift inspection).

The inspection must be complete and thorough, covering the surface of the entire length of the wire ropes, with particular attention given to all of the following:

Exception: In the event an inspection under paragraph (c)(2) of this section is not feasible due to existing set-up and configuration of the equipment (such as where an assist crane is needed) or due to site conditions (such as a dense urban setting), such inspections must be conducted as soon as it becomes feasible, but no longer than an additional 6 months for running ropes and, for standing ropes, at the time of disassembly.

If the deficiency is localized, the problem is corrected by severing the wire rope in two; the undamaged portion may continue to be used. Joining lengths of wire rope by splicing is prohibited. If a rope is shortened under this paragraph, the employer must ensure that the drum will still have two wraps of wire when the load and/or boom is in its lowest position.

Wire rope is often used in slings because of its strength, durability, abrasion resistance and ability to conform to the shape of the loads on which it is used. In addition, wire rope slings are able to lift hot materials.

Wire rope used in slings can be made of ropes with either Independent Wire Rope Core (IWRC) or a fiber-core. It should be noted that a sling manufactured with a fiber-core is usually more flexible but is less resistant to environmental damage. Conversely, a core that is made of a wire rope strand tends to have greater strength and is more resistant to heat damage.

Wire rope may be manufactured using different rope lays. The lay of a wire rope describes the direction the wires and strands are twisted during the construction of the rope. Most wire rope is right lay, regular lay. This type of rope has the widest range of applications. Wire rope slings may be made of other wire rope lays at the recommendation of the sling manufacturer or a qualified person.

Wire rope slings are made from various grades of wire rope, but the most common grades in use are Extra Improved Plow Steel (EIPS) and Extra Extra Improved Plow Steel (EEIPS). These wire ropes are manufactured and tested in accordance with ASTM guidelines. If other grades of wire rope are used, use them in accordance with the manufacturer"s recommendations and guidance.

When selecting a wire rope sling to give the best service, consider four characteristics: strength, ability to bend without distortion, ability to withstand abrasive wear, and ability to withstand abuse.

Rated loads (capacities) for single-leg vertical, choker, basket hitches, and two-, three-, and four-leg bridle slings for specific grades of wire rope slings are as shown in Tables 7 through 15.

Ensure that slings made of rope with 6×19 and 6x37 classifications and cable slings have a minimum clear length of rope 10 times the component rope diameter between splices, sleeves, or end fittings unless approved by a qualified person,

Ensure that braided slings have a minimum clear length of rope 40 times the component rope diameter between the loops or end fittings unless approved by a qualified person,

Do not use wire rope clips to fabricate wire rope slings, except where the application precludes the use of prefabricated slings and where the sling is designed for the specific application by a qualified person,

Although OSHA"s sling standard does not require you to make and maintain records of inspections, the ASME standard contains provisions on inspection records.[3]

Ensure that wire rope slings have suitable characteristics for the type of load, hitch, and environment in which they will be used and that they are not used with loads in excess of the rated load capacities described in the appropriate tables. When D/d ratios (Fig. 4) are smaller than those listed in the tables, consult the sling manufacturer. Follow other safe operating practices, including:

When D/d ratios (see Fig. 6) smaller than those cited in the tables are necessary, ensure that the rated load of the sling is decreased. Consult the sling manufacturer for specific data or refer to the WRTB (Wire Rope Technical Board) Wire Rope Sling Users Manual, and

Before initial use, ensure that all new swaged-socket, poured-socket, turnback-eye, mechanical joint grommets, and endless wire rope slings are proof tested by the sling manufacturer or a qualified person.

Permanently remove from service fiber-core wire rope slings of any grade if they are exposed to temperatures in excess of 180 degrees F (82 degrees C).

Follow the recommendations of the sling manufacturer when you use metallic-core wire rope slings of any grade at temperatures above 400 degrees F (204 degrees C) or below minus 40 degrees F (minus 40 degrees C).

Mishandling of workplace materials is the single largest cause of accidents in the workplace. Fortunately, most of these accidents are avoidable. With wire rope slings playing an important role with cranes, derricks, and hoists, it’s important to understand how to make a proper selection.

A wire rope sling is made of wire rope. It is composed of single wires that have been twisted into strands. These strands are then twisted to form a wire rope.

The strength of a wire rope sling is a function of size, grade, and construction. It needs to accommodate the applied maximum load. The more a sling is used, both the design and the sling’s strength are reduced. A sling loaded beyond it strength will fail. For older slings it’s important to inspect often.

Wire rope slings must be able to take repeated bending without wires failing due to fatigue, sometimes called bending without failure. The best way to preventing fatigue failure is to use blocking or padding to increase the radius of bend.

The ability of wire rope to withstand abrasion. It’s determined by size, number of wires, and construction of the rope. Remember that smaller wires bend easier and offer greater flexibility, which also means they are more susceptible to abrasion.

The misuse of a wire rope will cause the sling to be unsafe well before any other reason. Kinking or bird caging will reduce the strength of a wire rope. Bird caging is forcibly untwisting the wire rope strands and they become spread outward. Be sure to keep up proper use per the manufacturer specifications.

These are just four factors to consider when determining the best wire rope slings for your application. Keep in mind that weight, size, flexibility, and shape of the loads being handled will also affect the life of a wire rope sling.

Maintain a record for each rope that includes the date of inspection, type of inspection, the name of the person who performed the inspection, and inspection results.

Use the "rag-and-visual" method to check for external damage. Grab the rope lightly and with a rag or cotton cloth, move the rag slowly along the wire. Broken wires will often "porcupine" (stick out) and these broken wires will snag on the rag. If the cloth catches, stop and visually assess the rope. It is also important to visually inspect the wire (without a rag). Some wire breaks will not porcupine.

Measure the rope diameter. Compare the rope diameter measurements with the original diameter. If the measurements are different, this change indicates external and/or internal rope damage.

Visually check for abrasions, corrosion, pitting, and lubrication inside the rope. Insert a marlin spike beneath two strands and rotate to lift strands and open rope.

Assess the condition of the rope at the section showing the most wear. Discard a wire rope if you find any of the following conditions:In running ropes (wound on drums or passed over sheaves), 6 or more broken wires in one rope lay length; 3 or more broken wires in one strand in one rope lay. (One rope lay is the distance necessary to complete one turn of the strand around the diameter of the rope.)

Corrosion from lack of lubrication and exposure to heat or moisture (e.g., wire rope shows signs of pitting). A fibre core rope will dry out and break at temperatures above 120°C (250°F).

Kinks from the improper installation of new rope, the sudden release of a load or knots made to shorten a rope. A kink cannot be removed without creating a weak section. Discarding kinked rope is best.

The following is a fairly comprehensive listing of critical inspection factors. It is not, however, presented as a substitute for an experienced inspector. It is rather a user’s guide to the accepted standards by which wire ropes must be judged. Use the outline to skip to specific sections:

Rope abrades when it moves through an abrasive medium or over drums and sheaves. Most standards require that rope is to be removed if the outer wire wear exceeds 1/3 of the original outer wire diameter. This is not easy to determine, and discovery relies upon the experience gained by the inspector in measuring wire diameters of discarded ropes.

All ropes will stretch when loads are initially applied. As a rope degrades from wear, fatigue, etc. (excluding accidental damage), continued application of a load of constant magnitude will produce incorrect varying amounts of rope stretch.

Initial stretch, during the early (beginning) period of rope service, caused by the rope adjustments to operating conditions (constructional stretch).

Following break-in, there is a long period—the greatest part of the rope’s service life—during which a slight increase in stretch takes place over an extended time. This results from normal wear, fatigue, etc.

Thereafter, the stretch occurs at a quicker rate. This means that the rope has reached the point of rapid degradation: a result of prolonged subjection to abrasive wear, fatigue, etc. This second upturn of the curve is a warning indicating that the rope should soon be removed.

In the past, whether or not a rope was allowed to remain in service depended to a great extent on the rope’s diameter at the time of inspection. Currently, this practice has undergone significant modification.

Previously, a decrease in the rope’s diameter was compared with published standards of minimum diameters. The amount of change in diameter is, of course, useful in assessing a rope’s condition. But, comparing this figure with a fixed set of values can be misleading.

As a matter of fact, all ropes will show a significant reduction in diameter when a load is applied. Therefore, a rope manufactured close to its nominal size may, when it is subjected to loading, be reduced to a smaller diameter than that stipulated in the minimum diameter table. Yet under these circumstances, the rope would be declared unsafe although it may, in actuality, be safe.

As an example of the possible error at the other extreme, we can take the case of a rope manufactured near the upper limits of allowable size. If the diameter has reached a reduction to nominal or slightly below that, the tables would show this rope to be safe. But it should, perhaps, be removed.

Today, evaluations of the rope diameter are first predicated on a comparison of the original diameter—when new and subjected to a known load—with the current reading under like circumstances. Periodically, throughout the life of the rope, the actual diameter should be recorded when the rope is under equivalent loading and in the same operating section. This procedure, if followed carefully, reveals a common rope characteristic: after an initial reduction, the diameter soon stabilizes. Later, there will be a continuous, albeit small, decrease in diameter throughout its life.

Deciding whether or not a rope is safe is not always a simple matter. A number of different but interrelated conditions must be evaluated. It would be dangerously unwise for an inspector to declare a rope safe for continued service simply because its diameter had not reached the minimum arbitrarily established in a table if, at the same time, other observations lead to an opposite conclusion.

Corrosion, while difficult to evaluate, is a more serious cause of degradation than abrasion. Usually, it signifies a lack of lubrication. Corrosion will often occur internally before there is any visible external evidence on the rope surface.

Pitting of wires is a cause for immediate rope removal. Not only does it attack the metal wires, but it also prevents the rope’s component parts from moving smoothly as it is flexed. Usually, a slight discoloration because of rusting merely indicates a need for lubrication.

Severe rusting, on the other hand, leads to premature fatigue failures in the wires necessitating the rope’s immediate removal from service. When a rope shows more than one wire failure adjacent to a terminal fitting, it should be removed immediately. To retard corrosive deterioration, the rope should be kept well lubricated with a clear wire rope lube that can penetrate between strands. In situations where extreme corrosive action can occur, it may be necessary to use galvanized wire rope.

Kinks are tightened loops with permanent strand distortion that result from improper handling when a rope is being installed or while in service. A kink happens when a loop is permitted to form and then is pulled down tight, causing permanent distortion of the strands. The damage is irreparable and the sling must be taken out of service.

Doglegs are permanent bends caused by improper use or handling. If the dogleg is severe, the sling must be removed from service. If the dogleg is minor, exhibiting no strand distortion and cannot be observed when the sling is under tension, the area of the minor dogleg should be marked for observation and the sling can remain in service.

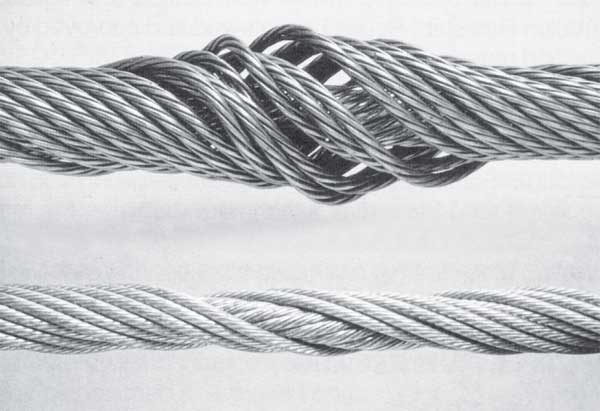

Bird caging results from torsional imbalance that comes about because of mistreatment, such as sudden stops, the rope being pulled through tight sheaves, or wound on too small a drum. This is cause for rope replacement unless the affected section can be removed.

Particular attention must be paid to wear at the equalizing sheaves. During normal operations, this wear is not visible. Excessive vibration or whip can cause abrasion and/or fatigue. Drum cross-over and flange point areas must be carefully evaluated. All end fittings, including splices, should be examined for worn or broken wires, loose or damaged strands, cracked fittings, worn or distorted thimbles and tucks of strands.

After a fire or the presence of elevated temperatures, there may be metal discoloration or an apparent loss of internal lubrication. Fiber core ropes are particularly vulnerable. Under these circumstances the rope should be replaced.

Continuous pounding is one of the causes of peening. This can happen when the rope strikes against an object, such as some structural part of the machine, or it beats against a roller or it hits itself. Often, this can be avoided by placing protectors between the rope and the object it is striking.

Another common cause of peening is continuous working-under high loads—over a sheave or drum. Where peening action cannot be controlled, it is necessary to have more frequent inspections and to be ready for earlier rope replacement.

Below are plain views and cross-sections show effects of abrasion and peening on wire rope. Note that a crack has formed as a result of heavy peening.

Scrubbing refers to the displacement of wires and strands as a result of rubbing against itself or another object. This, in turn, causes wear and displacement of wires and strands along one side of the rope. Corrective measures should be taken as soon as this condition is observed.

Wires that break with square ends and show little surface wear have usually failed as a result of fatigue. Such fractures can occur on the crown of the strands or in the valleys between the strands where adjacent strand contact exists. In almost all cases, these failures are related to bending stresses or vibration.

If diameter of the sheaves, rollers or drum cannot be increased, a more flexible rope should be used. But, if the rope in use is already of maximum flexibility, the only remaining course that will help prolong its service life is to move the rope through the system by cutting off the dead end. By moving the rope through the system, the fatigued sections are moved to less fatiguing areas of the reeving.

The number of broken wires on the outside of a wire rope are an index of its general condition, and whether or not it must be considered for replacement. Frequent inspection will help determine the elapsed time between breaks. Ropes should be replaced as soon as the wire breakage reaches the numbers given in the chart below. Such action must be taken without regard to the type of fracture.

* All ropes in the above applications—one outer wire broken at the point of contact with the core that has worked its way out of the rope structure and protrudes or loops out of the rope structure. Additional inspection of this section is required.

Rope that has either been in contact with a live power line or been used as “ground” in an electric welding circuit, will have wires that are fused, discolored and/or annealed and must be removed.

On occasion, a single wire will break shortly after installation. However, if no other wires break at that time, there is no need for concern. On the other hand, should more wires break, the cause should be carefully investigated.

On any application, valley breaks—where the wire fractures between strands—should be given serious attention. When two or more such fractures are found, the rope should be replaced immediately. (Note, however, that no valley breaks are permitted in elevator ropes.)

It is good to remember that once broken wires appear—in a rope operating under normal conditions—a good many more will show up within a relatively short period. Attempting to squeeze the last measure of service from a rope beyond the allowable number of broken wires (refer to table on the next page) will create an intolerably hazardous situation.

Recommended retirement criteria for all Rotation Resistant Ropes are 2 broken wires in 6 rope diameters or 4 broken wires in 30 rope diameters (i.e. 6 rope diameters for a 1″ diameter rope = 6″).

Distortion of Rotation Resistant Ropes, as shown below, can be caused by shock load / sudden load release and/or induced torque, and is the reason for immediate removal from service.

Installing wire rope on the drum: If a reel stand is used, take care that the drum is spooled from the top and that the reel feeds from the top. This avoids causing a reverse bend in the wire. A reverse bend will cause spooling problems and damage the wire rope.

When spooling from a reel, make sure a tension device is used so the reel will not overrun the rope. If using a mallet to align rope as it feeds onto the drum, use one with a plastic or rubber-coated face. Do not strike wire rope with a metal-faced hammer or mallet.

Avoid spooling more wire rope onto a drum than is needed. The last layer must be at least two rope diameters below the drum flange top. Spooling more wire rope than is necessary will increase crushing and may cause the rope to jump the flange.

Prevent kinks in the wire: If a loop forms during unreeling STOP! Pulling on a loop will produce a kink that will not work itself out. A kink is a permanent defect and will cause increased wear on the drum, sheaves and the wire rope itself. If kinks must be cut out of the rope, make sure enough rope remains on the drum to provide 2 or 3 wraps (manufacture’s recommendation) on the drum when the crane is extended full range.

Keep the wire rope lubricated: Rust and dirt can deteriorate and weaken a wire rope. In addition, rust and dirt act as an abrasive on the rope as it spools through the sheaves and drums. Lubrication of the rope allows individual wires to move and work together so that all the wires carry the load instead of just a few. Weather and other exposures can also remove the lubricant and allow rust to form.

When inspecting wire rope, first clean the rope using a wire brush, solvent or steam cleaner. Next, inspect the entire rope for damage in accordance with OSHA 1926.550. Once the rope has passed inspection, lubricate it well. Good lubricants are thin enough to penetrate all the way to the core but thick enough to coat each wire individually.

The best method for assuring proper cleaning and lubrication is to use a manufactured lubrication system. These systems work in the following steps: (1) all corrosion and rust is removed; (2) pressure forces out all moisture; and (3) a high-pressure pump forces lubricant throughout the entire rope.

Take rigging for granted and it could be your downfall! Cranes are only as reliable as each of their rigging components. The capacity of wire rope is based on new or well-maintained rope. Its strength can dramatically decrease if it’s poorly cared for. The rope may look strong, but is it safe? Human life and valuable property may depend upon your answer!

Do you know who is supposed to be inspecting your lifting slings? More importantly, do you know how often they’re inspecting them? OSHA and ASME have different inspection requirements, frequencies, and removal criteria for each type of sling—including alloy chain slings, synthetic slings, metal mesh slings, and wire rope slings.

In this article, our goal is to help you understand what is required to inspect wire rope slings to meet ASME standards, which in turn, will help to ensure the safety of the users,help extend the service life of the slings, and help reduce unnecessary equipment repair costs and loss of production due to equipment downtime.

As a starting point, the same work practices which apply to all “working” wire rope apply to wire rope which has been fabricated into a sling. Therefore, a good working knowledge of wire rope design and construction will not only be useful, but essential in conducting a wire rope sling inspection.

There are two industry standards that exist to provide the end-user with guidelines for inspection and criteria that warrants removal from service: OSHA 1910.184 and ASME B30.9.

Initial Inspection (prior to initial use): Best practice is to inspect the wire rope sling upon receiving it from the manufacturer. Double-check the sling tag to make sure it’s what you ordered and that the rated capacity meets all of your project specifications and lifting requirements.

Frequent (daily or prior to use): Designate a Competent Person to perform a daily visual inspection of slings and all fastenings and attachments for damage, defects, or deformities. The inspector should also make sure that the wire rope sling that was selected meets the specific job requirements it’s being used for.

Users can’t rely on a once-a-day inspection if the wire rope sling is used multiple times throughout the day. Damage to wire rope can occur on one lift and best practice is to perform a visual inspection before any shift change or changes in lifting application. Because shock loads, severe angles, sharp edges, and excessive heat can quickly cause damage to a lifting sling, the user should inspect the sling prior to each lift.

Depending on the severity of the operating environment and frequency of use, your business may decide to inspect wire rope slings more often than the minimum yearly requirement.

Per ASME B30.9, the wire rope sling tag on all new slings shall be marked by the manufacturer to include:Rated load for the types of hitches (single-leg vertical, choker, and basket) and the angle upon which they are based

The goal of a sling inspection is to evaluate remaining strength in a sling which has been used previously to determine if it is suitable for continued use. When inspecting wire rope slings, daily visual inspections are intended to detect serious damage or deterioration which would weaken the sling.

This inspection is usually performed by the person using the sling in a day-to-day job. The user should look for obvious things, such as broken wires, kinks, crushing, broken attachments, severe corrosion, etc. Any deterioration of the sling which could result in appreciable loss of original strength should be carefully noted and determination made on whether further use would constitute a safety hazard.

2. Broken Wires: For strand-laid grommets and single-part slings, ten randomly distributed broken wires in one rope lay, or five broken wires in one strand in one rope lay. For cable laid, cable laid grommets and multi-part slings, use the following:

3. Distortion: Kinking, crushing, birdcaging or other damage which distorts the rope structure. The main thing to look for is wires or strands that are pushed out of their original positions in the rope.

7. Corrosion: Severe corrosion of the rope or end attachments which has caused pitting or binding of wires should be cause for replacing the sling. Light surface rust does not substantially affect strength of a sling.

9. Unbalance:A very common cause of damage is the kink which results from pulling through a loop while using a sling, thus causing wires and strands to be deformed and pushed out of their original position. This unbalances the sling, reducing its strength.

10. Kinks: Are tightened loops with permanent strand distortion that result from improper handling when a rope is being installed or while in service. A kink happens when a loop is permitted to form and then is pulled down tight, causing permanent distortion of the strands. The damage is irreparable and the sling must be taken out of service.

11. Doglegs: Are permanent bends caused by improper use or handling. If the dogleg is severe, the sling must be removed from service. If the dogleg is minor, (exhibiting no strand distortion) and cannot be observed when the sling is under tension, the area of the minor dogleg should be marked for observation and the sling can remain in service.

The best lifting and rigging inspection program is of no value if slings, which are worn out and have been retired, are not properly disposed of. When it is determined by the inspector that a sling is worn out or damaged beyond use, it should be tagged immediately DO NOT USE.

If it’s determined that the wire rope will be removed from service, we suggest cutting it down into more manageable sizes before discarding. This extra effort will help to accommodate the needs of most recycling facilities that will accept the damaged wire rope and also help to make sure that it cannot be used any further. Keep the following in mind when disposing of wire rope slings and wire rope cable:Cut into approximately 3’ to 4’ sections

OSHA does not provide clear guidelines on how to properly and adequately inspect wire rope slings. It is up to the designated inspection personnel to know the requirements of the sling inspection standards, and to develop a comprehensive inspection protocol. Wire rope inspection should follow a systematic procedure:First, it is necessary that all parts of the sling are readily visible. The sling should be laid out so every part is accessible.

Next, the sling should be sufficiently cleaned of dirt and grease so wires and fittings are easily seen. This can usually be accomplished with a wire brush or rags.

The best way to help extend the life of a wire rope sling, and help to ensure that it stays in service, is to properly maintain it during and in-between each use. Inspections are easier to perform—and probably more thorough—when slings are easily accessible and organized, kept off of the ground, and stored in a cool and dry environment.Hang slings in a designated area where they are off of the ground and will not be subjected to mechanical damage, corrosive action, moisture, extreme temperatures, or to kinking.

Like any other machine, wire rope is thoroughly lubricated at time of manufacture. Normally, for sling use under ordinary conditions, no additional lubrication is required. However, if a sling is stored outside or in an environment which would cause corrosion, lubrication should be applied during the service life to prevent rusting or corroding.

If lubrication is indicated, the same type of lubrication applied during the manufacturing process should be used. Your sling manufacturer can provide information on the type of lubricant to be used and provide the best method of application. We recommend a wire rope lubricant that is designed to penetrate and adhere to the wire rope core.

Proper inspection of your wire rope slings for damage or irregularities, prior to each use, is the best way to help keep everybody on the job site safe. Keep in mind that you’re planning to lift valuable and expensive equipment, and if a failure were to occur, it would not only cause unnecessary equipment repair costs and costly downtime, but also potentially jeopardize the lives of workers on site.

At Mazzella, we offer a variety of services including site assessments, rigging and crane operator training, sling inspection and repairs, overhead crane inspections and so much more. Our rigging inspection program is its own dedicated business unit with a team of inspectors that are certified through Industrial Training International to meet OSHA 1910.184 and ASME B30.9 requirements for sling inspection.

Hoisting loads with a wire rope is a simple operation. Hook it up; lift it. Turns out, it’s more complicated than it appears. The details of setting up, inspecting, and maintaining lifts with wire ropes are not complicated, but are critical. A lift that goes awry is dangerous. A bad lift puts workers at risk. In this article, we discuss the causes of wire rope failure and how to avoid them.

Abrasion breaks are caused by external factors such as coming into contact with improperly grooved sheaves and drums. Or just hitting against some object during operation. Worn, broken wire ends is the result of an abrasion break. Common causes of abrasion breaks include:

Core slippage or protrusion is caused by shock load or improper installation of the wire rope. Excessive torque can cause core slippage that forces the outer strands to shorten. The core will then protrude from the rope. Wire ropes designed to be rotation-resistant should be handled carefully so as not to disturb its lay length.

Corrosion breaks cause pitting on the individual wires that comprise the rope. This type of damage is caused by poor lubrication. However, corrosion breaks are also caused by the wire rope coming into contact with corrosive chemicals, such as acid.

There are many ways the strands of a rope can be crushed or flattened. Improper installation is a common cause. To avoid crushing, you’ll want the first layer of the wire rope to be very tight. You’ll also need to properly break-in a new wire rope. Other causes of crushing include cross winding, using a rope of the wrong diameter, or one that it too long.

Cracks to individual wires are caused by fatigue breaks. Fatigue breaks happen because the wire rope is being bent over the sheave over and over again. In time, the constant rubbing of the wire rope against the sheave or drum causes these breaks. Sheaves that are too small will accelerate fatigue breaks because they require more bending. Worn bearings and misaligned sheaves can also cause fatigue. A certain number of broken wires is acceptable. The worker responsible for equipment inspection prior to use should know the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) standard for wire ropes. The ASME standard determines whether the wire rope must be replaced. (https://www.asme.org/)

Selecting the right wire rope for the job is critical. There is never a perfect rope. For example, you will need to make a tradeoff between fatigue resistance and abrasion resistance. There are several aspects to wire rope design to consider, including:

In general, the proper wire rope will have a strength rating high enough to handle the load. (Strength is rated in tons.) It can handle the stress of repeated bending as it passes over sheaves or around drums. How you attach the rope in preparation for the lift matters and should only be handled by properly trained workers.

The wire rope (and all the equipment involved in a lift) should be fully inspected prior to the lift. The worker performing the inspection should be well-versed in the types of damage that can cause a wire rope to fail. Using a checklist is highly recommended. This will ensure that the inspection is complete. Worker and supervisor signoff will increase accountability. Of course, the wire rope must be maintained according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

How a wire rope is stored, the weather conditions in which it is used, and how they are cleaned all affect its useful life. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) provides these recommendations: (Source: https://www.osha.gov/dsg/guidance/slings/wire.html)

Preventing wire rope failures starts with selecting the right one for the job. When in doubt, talk with your local equipment dealer. Be prepared to discuss your specific job requirements. A thorough inspection of the wire rope prior to using it is critical. Finally, properly store your wire rope. The selection, inspection, and care of wire rope is key to job safety.

Wire rope is extremely sturdy and can be used in many different applications. In order to withstand harsh conditions, wire rope has basic guidelines of inspection it must meet. Continue reading to find out the guidelines of inspection for wire rope.

Abrasion damage is usually caused by the rope making contact with an abrasive surface. It can also be caused by simply passing over the drum and sheaves during regular, continued use. To minimize this risk, all components should be in proper working condition and be of appropriate diameter for the rope. Badly worn sheaves or drums will cause serious damage to a new rope and will greatly diminish the integrity of the rope quickly.

Corrosion is hard to assess but is more problematic than abrasion. Corrosion is usually the result of the lack of lubrication. It will most likely take place internally before there are any apparent signs on the rope’s surface. One telltale sign of corrosion is a slight discoloration, which is generally the result of rusting. This discoloration indicates a need for lubrication which should be dealt with as soon as possible. Failure to attend to this situation will lead to severe corrosion which will cause premature fatigue failures in the wires and strands. If this occurs, the rope will need to be removed immediately.

Diameter reduction is an extremely serious deterioration factor and can occur for several reasons. The most common reasons for diameter reduction are excessive abrasion of the outside wires, loss of core diameter/support, internal or external corrosion damage, or inner wire failure.

Examining and documenting a new rope’s actual diameter when under normal load conditions is critical. During the life of the rope, the actual diameter of the rope should be regularly measured at the same location under similar loading conditions. If this protocol is followed correctly, it should divulge a routine rope characteristic—after an initial reduction, the overall diameter will stabilize, then gradually decrease in diameter during the course of the rope’s life. This occurrence is completely natural, but if diameter reduction is confined to a single area or happens quickly, the inspector must quickly identify the source of the diameter loss and make the necessary changes if possible. Otherwise, the rope should be replaced as soon as possible.

Crushing or flattening of wire rope strands can happen for many reasons. These issues usually arise on multilayer spooling conditions but can also develop just by using the wrong wire rope for the specific application. Incorrect installation is the most common cause of premature crushing/flattening. Quite often, failure to secure a tight first layer, which is known as the foundation, will cause loose or “gappy” conditions in the wire rope which will result in accelerated deterioration. Failure to appropriately break-in the new rope, or even worse, to have no break-in protocol whatsoever, will also result in poor spooling conditions. The inspector must understand how to correctly inspect the wire rope, in addition to knowing how that rope was initially installed.

Another potential cause for the replacement of the rope is shock loading (also known as bird-caging). Shock loading is caused by the abrupt release of tension on the wire rope and its rebound culminating from being overloaded. The damage that ensues can never be amended and the rope needs to be replaced immediately.

There are several different instances that might result in high stranding. Some of these instances include the inability to correctly seize the rope prior to installation or the inability to maintain seizing during wedge socket installation. Sometimes wavy rope occurs due to kinks or very tight grooving issues. Another possible problem arises from introducing torque or twist into a new rope during poor installation methods. In this situation, the inspector must assess the continued use of the rope or conduct inspections more often.

There are a lot of guidelines for troubleshooting wire rope. At Silver State Wire Rope and Rigging, Inc., we take these guidelines seriously, and so should you. All of our products are tested and guaranteed to be the best fit for your specific needs. We can also help you with your troubleshooting needs. Contact us today!

Any wire rope in use should be inspected on a regular basis. You have too much at stake in lives and equipment to ignore thorough examination of the rope at prescribed intervals.

The purpose of inspection is to accurately estimate the service life and strength remaining in a rope so that maximum service can be had within the limits of safety. Results of the inspection should be recorded to provide a history of rope performance on a particular job.

On most jobs wire rope must be replaced before there is any risk of failure. A rope broken in service can destroy machinery and curtail production. It can also kill.

Because of the great responsibility involved in ensuring safe rigging on equipment, the person assigned to inspect should know wire rope and its operation thoroughly. Inspections should be made periodically and before each use, and the results recorded.

When inspecting the rope, the condition of the drum, sheaves, guards, cable clamps and other end fittings should be noted. The condition of these parts affects rope wear: any defects detected should be repaired.

To ensure rope soundness between inspections, all workers should participate. The operator can be most helpful by watching the ropes under his control. If any accident involving the ropes occurs, the operator should immediately shut down his equipment and report the accident to his supervisor. The equipment should be inspected before resuming operation.

The Occupational Safety and Health Act has made periodic inspection mandatory for most wire rope applications. If you need help locating the regulations that apply to your application, please give our rigging experts a call.

One piece of equipment most often used in the steel erection industry is the wire rope sling. It is also one of the most abused pieces of equipment. There are many ways wire rope slings are abused, including being laid in the dirt; pulled out from under a load by the crane; used without softeners when lifting heavy loads; or being straightened by an old-school choker straightener. Straightening your slings over and over weakens the wires and you lose the strength of your sling. These are all unacceptable practices. Wire rope slings must be visually inspected before each day’s use. During inspection, you must know and understand what to look for to determine whether you should continue to use or discard the sling.

The ASME volume B30.9-2018: Slings revises the 2014 edition, and contains changes pertaining to wire-rope slings, starting with a new section on “Rigger Responsibilities.” Those changes include: Clarified that a qualified person should, if necessary, determine additional steps that need to be taken after identifying a hazard during inspection.

Early signs of wire rope sling failure can actually provide the user with a margin of safety. A wire sling needs to be discarded when it shows signs of:Severe corrosion,

The goal of a sling inspection is to evaluate remaining strength in a previously used sling to determine its suitability for continued use. Daily visual inspections, designed to detect serious damage or deterioration that would weaken the sling, are usually performed by the person using the sling daily. Obvious issues, such as broken wires, kinks, crushing, broken attachments, and severe corrosion, should be looked for. Any deterioration that could result in appreciable loss of original strength should be noted to determine if further use would result in a safety hazard.

Train all employees in the safe use of rigging and proper rigging gear inspect inspection before each use. No more than three broken wires in a rope lay are allowed. Wire rope slings, like chain slings, must be cleaned prior to each inspection because they are subject to damage hidden by dirt or oil. In addition, they must be lubricated according to manufacturer"s instructions. Lubrication prevents or reduces corrosion and wear due to friction and abrasion. Before applying any lubricant, however, the sling user should make certain that the sling is dry. Applying lubricant to a wet or damp sling traps moisture against the metal and hastens corrosion. Corrosion deteriorates wire rope. It may be indicated by pitting, but it is sometimes hard to detect. If a wire rope sling shows any sign of significant deterioration, that sling must be removed until it can be examined by a person who is qualified to determine the extent of the damage. Using rigging racks or storing slings in a Conex storage container is always a best practice. Using with the correct size of shackle while choking slings will prolong the life of the sling. Finally, a monthly inspection color code program will assure inspections are being performed.

Three industry standards provide the end-user with guidelines for inspection and criteria that warrants removal from service: OSHA 1926.251(c)(4)(iv) for Construction), OSHA 1910.184 for General Industry) and ASME B30.9.

This detailed blog post from Mazzella Companies outlines the specifics on how to inspect wire rope slings, when to discard slings, and how often to inspect them.

On Feb. 25, the Office of Safety and Mission Assurance (OSMA) and Goddard Space Flight Center hosted a wire rope seminar led by expert Roland Verreet of Wire Rope Technology Aachen (Germany). Verreet is a frequent lecturer, author and consultant on wire ropes.

Wire rope, or cable, is a crucial component in lifting devices and equipment (LDE), and regular inspections are a requirement of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), industry standards, and NASA.

“Wire rope has a number of failure modes that those of us who haven’t studied it for a lifetime don’t give a lot of thought,” explained OSMA Pressure and Energetic Systems Safety Manager Owen Greulich.

Verreet showed participants what to look for and where to look in order to avoid wire rope failures. For example, he described a difficult-to-detect failure mode that can occur on the underside of the rope’s strands where the strands contact with the steel core. He explained that these breaks can be revealed by bending the rope, which will cause the breaks to detach from the main bodies of the strands. Verreet also discussed potential failures due to reduction of diameter, corrosion and deformation.

By understanding how wire rope works and how it can wear and fail, safety practitioners can better focus their inspections and better identify compromises in the integrity of the wire rope.

“The audience went away with a better appreciation of the complexity of wire rope,” stated Greulich. “In general, they had a better understanding of [wire rope] usage, failures and inspection, and had a place to go to for more information [Verreet’s online wire rope resource].”

The seminar was very well received, with many of the attendees complimenting Verreet’s informative and engaging presentations. One OSHA representative told Greulich that he wished he had attended this seminar 15 years ago when he was working in the field.

8613371530291

8613371530291