apollo 11 mission parts free sample

Left: Apollo 11 basalt 10049. This sample has a mass of 193 grams. The ruler scale is in centimeters. Right: Apollo 11 breccia 10018. This sample has a mass of 213 grams and is up to 8 centimeters across.

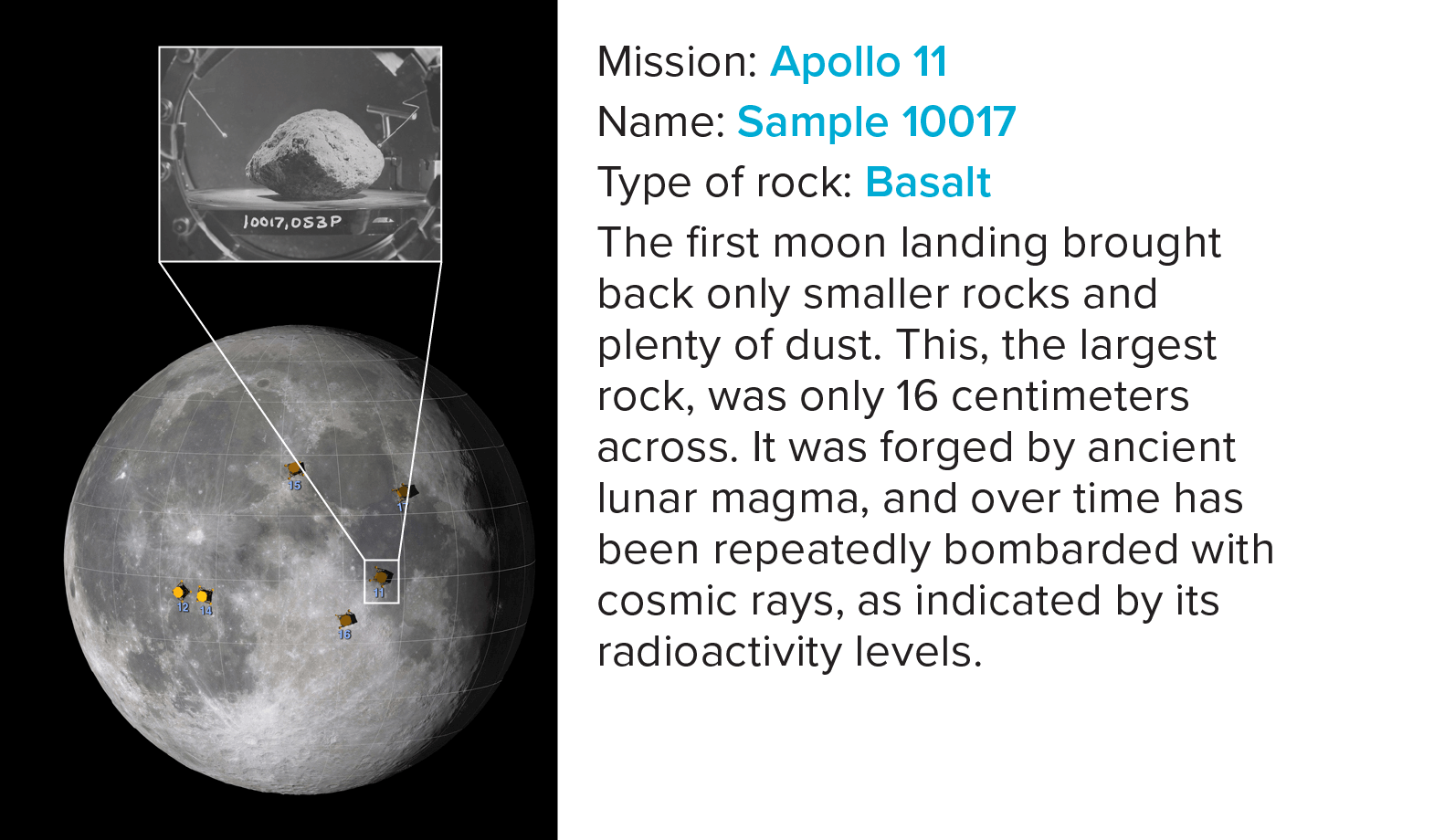

Apollo 11 carried the first geologic samples from the Moon back to Earth. In all, astronauts collected 21.6 kilograms of material, including 50 rocks, samples of the fine-grained lunar regolith (or "soil"), and two core tubes that included material from up to 13 centimeters below the Moon"s surface. These samples contain no water and provide no evidence for living organisms at any time in the Moon"s history.

The overall set of lunar samples collected during the Apollo program can be classified into three major rock types, basalts, breccias, and lunar highland rocks. Apollo 11 mainly collected basalts and breccias. However, small but important fragments of the Moon’s highland crust were found in some Apollo 11 breccias and were interpreted as evidence for an early “magma ocean” on the Moon. This was one of the major scientific findings of the Apollo 11 mission.

Basalts are rocks solidified from molten lava. On Earth, basalts are a common type of volcanic rock and are found in places such as Hawaii. Basalts are generally dark gray in color; when one looks at the Moon in the night sky, the dark areas are basalt. The basalts found at the Apollo 11 landing site are generally similar to basalts on Earth and are composed primarily of the minerals pyroxene and plagioclase. One difference is that the Apollo 11 basalts contain much more of the element titanium than is usually found in basalts on Earth. As a result, the mineral ilmenite is abundant in Apollo 11 basalts. Another titanium-bearing mineral, armalcolite, was first discovered in the Apollo 11 samples and was named for the first syllables of the last names of the three Apollo 11 astronauts. The basalts found at the Apollo 11 landing site range in age from 3.6 to 3.9 billion years and were formed from at least two chemically distinct magma sources. Prior to the lunar landings, some scientists thought that the Moon might have always been a cold, undifferentiated body. The discovery of basalt, which was once molten magma, disproved this hypothesis.

Breccias are rocks that are composed of fragments of older rocks. Over its long history, the Moon has been bombarded by countless meteorites. These impacts have broken many rocks up into small fragments. The heat and pressure of such impacts sometimes fuses small rock fragments into new rocks, called breccias. The Apollo 11 samples are referred to as regolith breccias because they formed by fusing material from the lunar regolith at the landing site. Many fragments can be seen in the breccia photograph shown above. The rock fragments in these breccias can include both mare basalts as well as material from the lunar highlands.

The lunar highlands are primarily a light-colored rock known as anorthosite, which consists primarily of the mineral plagioclase. It is very rare to find rocks on Earth that are virtually pure plagioclase. On Apollo 11, small fragments of anorthosite were found in some of the breccias. On later missions, the crews were specifically trained to look for large samples of anorthosite, with important samples being returned by Apollos 15 and 16.

On the Moon, it is believed that the anorthosite layer in the highland crust formed very early in the Moon"s history when much of the Moon"s outer layers were molten. This stage in lunar history is now known as the magma ocean. The plagioclase-rich anorthosite floated on the magma ocean like icebergs in the Earth"s oceans. The magma ocean hypothesis of an early, molten Moon was first developed from studies of the chemistry of Apollo 11 samples, although the term “magma ocean” was not actually used until a few years later. The magma ocean stage occurred 4.3 to 4.5 billion years ago, during the Moon’s initial formation. After the Moon cooled and solidified, small portions of the Moon remelted to form the basalts found at the Apollo 11 landing site and other parts of the Moon, in some cases more than a billion years after the Moon formed.

Scientific Discoveries from the Apollo 11 Mission – This article from Planetary Science Research Discoveries provides more details about the discoveries made with the Apollo 11 samples.

Commentary: Thirty seconds and counting. Astronauts report it feels good. T-25 seconds. Twenty seconds and counting. T-15 seconds, guidance is internal. 12, 11, 10, 9 ... ignition sequence start ... 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0 ... All engines running. Liftoff! We have a liftoff ... 32 minutes past the hour, liftoff on Apollo 11. Tower clear.

On July 20, 1969, Man took their first steps on the moon. This was an enormous triumph for NASA, but also the United States as a whole. It is a day in history that paved the way for many future space missions and discoveries, and it is one that will most definitely not be forgotten. In my essay, I will highlight the details and speculations of Apollo 11, the first manned moon landing.

The three astronauts on the Apollo 11 mission were Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins. Neil Armstrong was born in Wapakoneta, Ohio, on August 5, 1930. Armstrong went to college for aerospace and aeronautical engineering at Purdue University and the University of Cincinnati, and he served in the Korean War. He married his first wife, Janet Shearon on January 28, 1956. They were married until their divorce in 1994, and had three children; Karen, Eric, and Mark Armstrong. He was remarried to his second wife, Carol Held Knight, on June 12, 1994, and they were married until Armstrong’s death. In 1962, he joined NASA’s astronaut program. His first mission was Gemini Vlll, which launched in 1966, and he served as its command pilot. Of the three astronauts, he was the first man ever to walk on the moon. Neil Armstrong passed on August 25, 2012, at the age of 82 due to complications from an operation he had on his heart.

Buzz Aldrin was born on January 20, 1930, in Montclair, New Jersey. Before being recruited to fly with NASA, he served as a fighter pilot in the Korean War. Although not currently married, he has had three wives. The first was Joan Archer, who he was married to from 1954 to 1974. The second was Beverly Van Zile, and they were married from 1975 to 1978. His third wife was Lois Driggs Cannon, and he was married to her from 1988 to 2012. His first space mission was Gemini 12, which NASA chose him for in 1963. He also served as the lunar module pilot on the Apollo 11 mission, and was the second man to walk on the moon. Aldrin is currently 89 years old.

Michael Collins was born on October 30, 1930, in Rome, Italy. Collins married Patricia Finnegan in 1957, and they were married until her death in 2014. Together they had three children, Kate, Michael, and Ann Collins. He received his Bachelor of Science degree from Westpoint in 1952, and in 1966 he partook in his first space mission, Gemini 10. On this mission he performed a spacewalk. On the Apollo 11 mission, he never actually walked on the moon, but instead was assigned to remain in the command module. He is now 88 years old. All three astronauts were given the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Despite the award, Collins is often forgotten in the mission, and people give the credit to Armstrong and Aldrin.

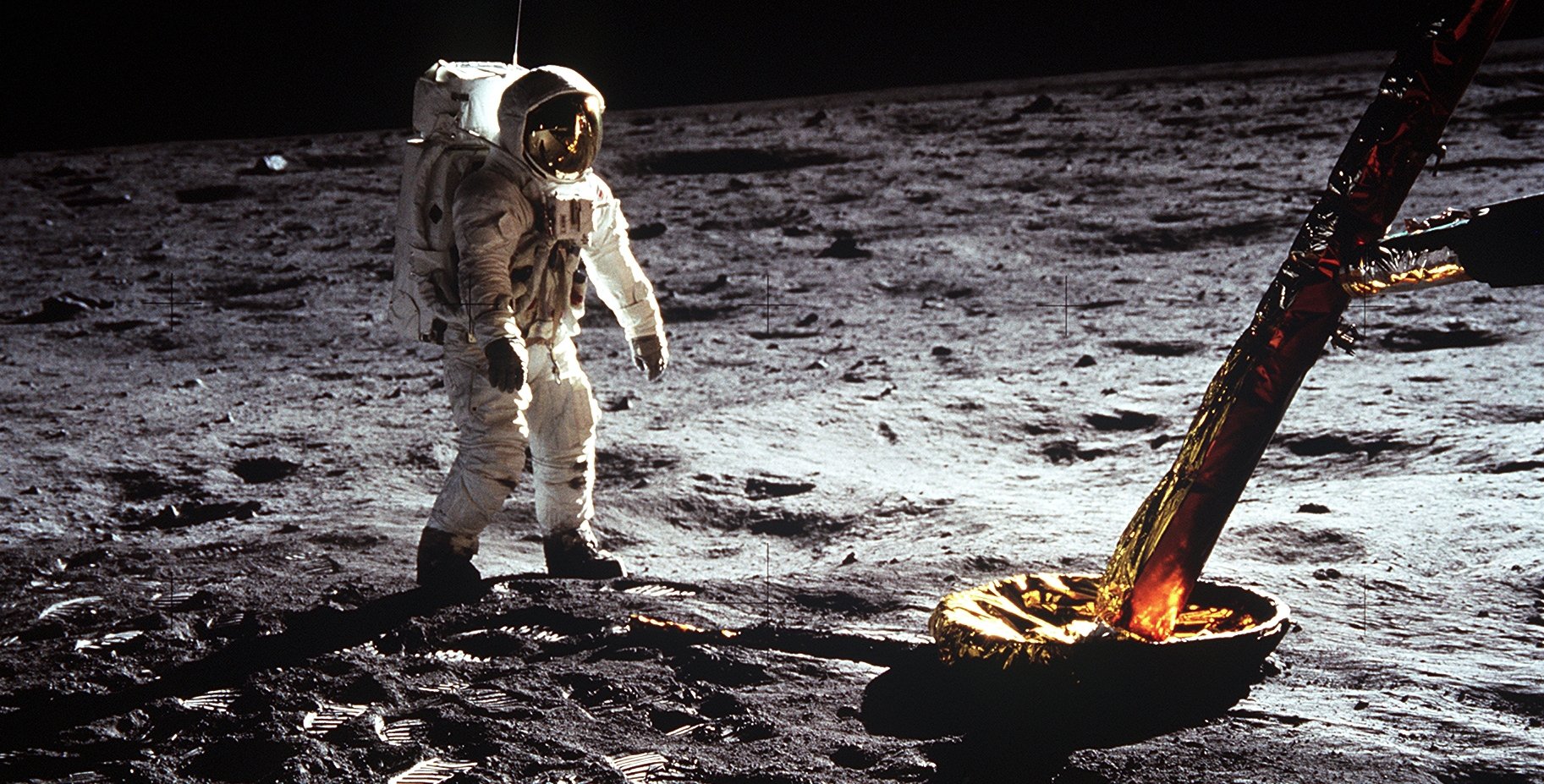

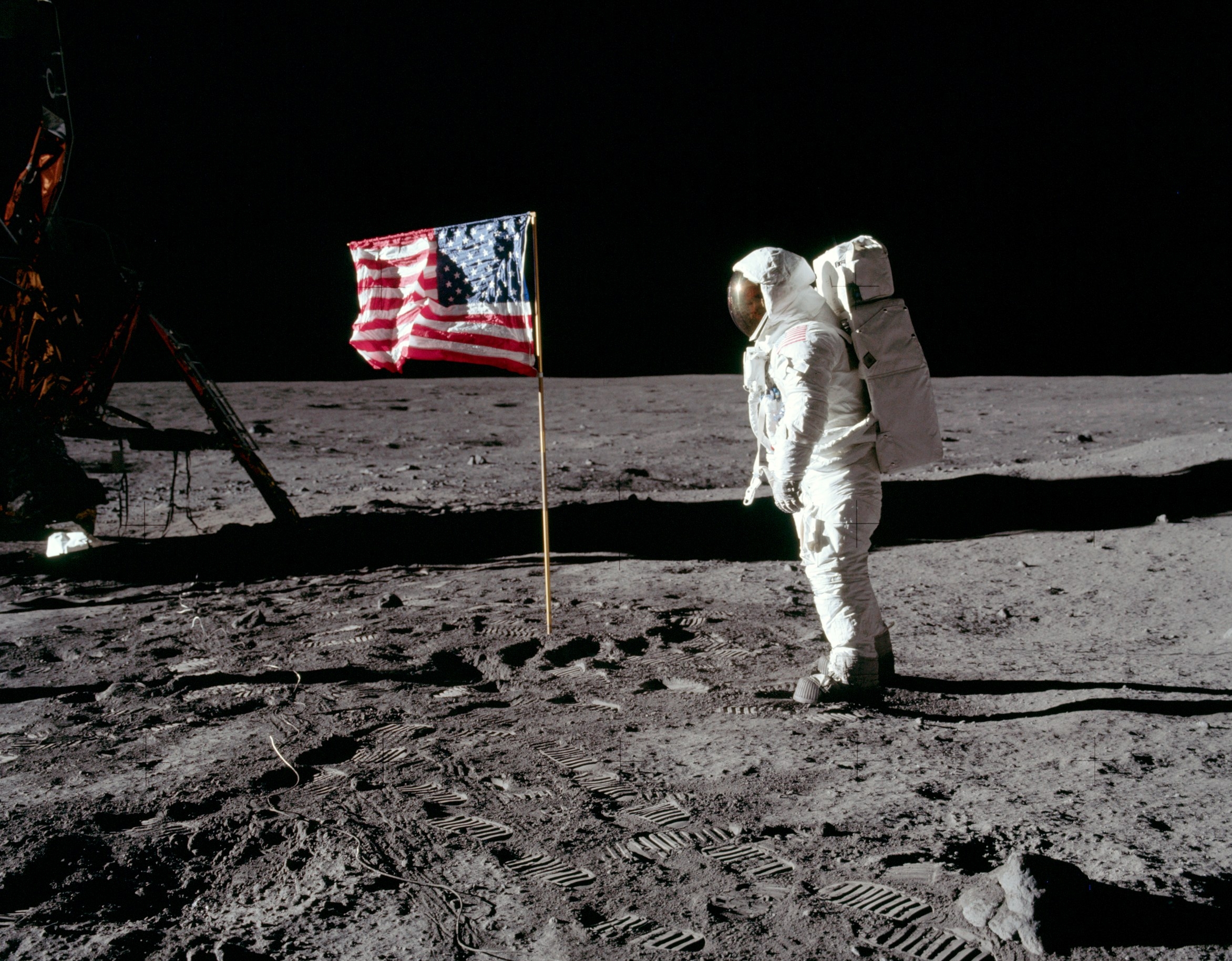

They make a landing on the moon at 4:18 PM on July 20, 1969. Upon landing, Armstrong famously reports back to mission control, saying, “Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed”. After hearing this, everyone watching from Kennedy Space Center begins to cheer and rejoice in this momentous time. After their successful landing, they prepare to make the first human steps on the moon. At this point, more than half a billion people are watching the live recording on television, waiting to see an astronaut emerge from the Eagle. At 10:56 PM, Neil Armstrong becomes the first man ever to step foot on the moon. With the world watching, he says, “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind’ (Dunbar 1). Moments later, Buzz Aldrin joins Armstrong on the moon’s surface, making him the second person ever to step foot on the moon. They take photographs and collect samples for the next two and a half hours, which they will bring back to Earth to help NASA make new discoveries. In addition to taking, they leave behind as well. Armstrong and Aldrin plant an American flag on the moon, and patch that was in remembrance of the fatal Apollo 1 disaster. It claimed the lives of all three astronauts on board. The also leave behind a plaque on on of the Eagles legs reading, ‘Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon. July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind’. After all of this, the men blast off of the moon’s surface and join Collins in the command module. On July 24, 1969, all three men splash down in the Columbia off the coast of Hawaii, into the Pacific Ocean. This means that Kennedy’s wish before his death is completed. America is the first country to put a man on the moon and bring him home to his family.

The Apollo 11 mission helped further many scientific experiments as well. The samples the astronauts brought home with them taught scientists many new things that have tremendously helped us, and will most definitely continue to help us as well. Apollo 11 gave us the very first geological samples from the moon. 22 kilograms of materials were carried back to Earth by Armstrong and Aldrin. This total includes over 50 rocks, soil from the surface of the moon, and material that they took from around 13 centimeters under the ground. However, none of the samples they brought back showed any signs of life, whether simple or not simple, and no water was found in the samples either. These specific samples were unable to prove that life has ever existed on the moon. At their landing site, two main types of rocks were found; basalt and breccia.

One reason people discredit Apollo 11 is because of the Van Allen belts. This is the most popular conspiracy. These Van Allen belts are simply two very large belts of radiation. They extend around the Earth, being compressed by high energy particles that they are hit with by wind from the sun, and are shaped by our Earth’s atmospheric magnetic field. Theorists believe that a human being would not be able to travel through these high energy bands without dying from extreme amounts of constant radiation. Before the Apollo 11 mission, NASA had already been accustomed to the Van Allen belts. In the 1950’s, mission like the Luna, Explorer, and pioneer taught us all we needed to know about them. One thing to note is that the intensity of radiation from these belts is constantly changing with the Sun’s activity. During the launch of Apollo 11, the radiation intensity was the lowest of the year, making it safe for the astronauts to pass through. If the astronauts did not experience safe conditions in the Van Allen belts, they would have gotten radiation sickness. Radiation is measured in the unit ‘rads’, and getting radiation sickness means that you have been exposed to anywhere from 200 to 1,000 rads in a span of around three hours. On the astronauts’ journey through the Van Allen belts, they were subjected to an estimated 18 rads over a 2 hour traveling time, meaning they were completely unaffected by the radiation. Those who the spaceship that touched the moon worked hard to make sure it was well insulated, allowing minimal amounts of radiation to pass through. In fact, it was determined that during their mission, Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins only received about as much radiation as they would have in a standard X-ray machine. This theory is easily disproved by statistics and scientific evidence harvested from NASA.

This year, on July 20, we will celebrate the 50 years since astronauts from the United States became the first people ever to step foot on the moon. Since then, countless more have had their chance to see the moon as well. The Apollo 11 mission paved the way for NASA to become stronger and better, and the world will never forget the incredible impact it had.

:focal(3360x2240:3361x2241)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b4/7f/b47f6e6f-2612-495e-8801-63d58f757b1d/lunar_dust_-_close_up.jpg)

Getting to space, and landing, traveling, and researching on the Moon posed a unique challenge to humankind. With such an unparalleled mission at hand, astronauts had to use specialized tools and technology made for space. Find a sample of some of these items below.

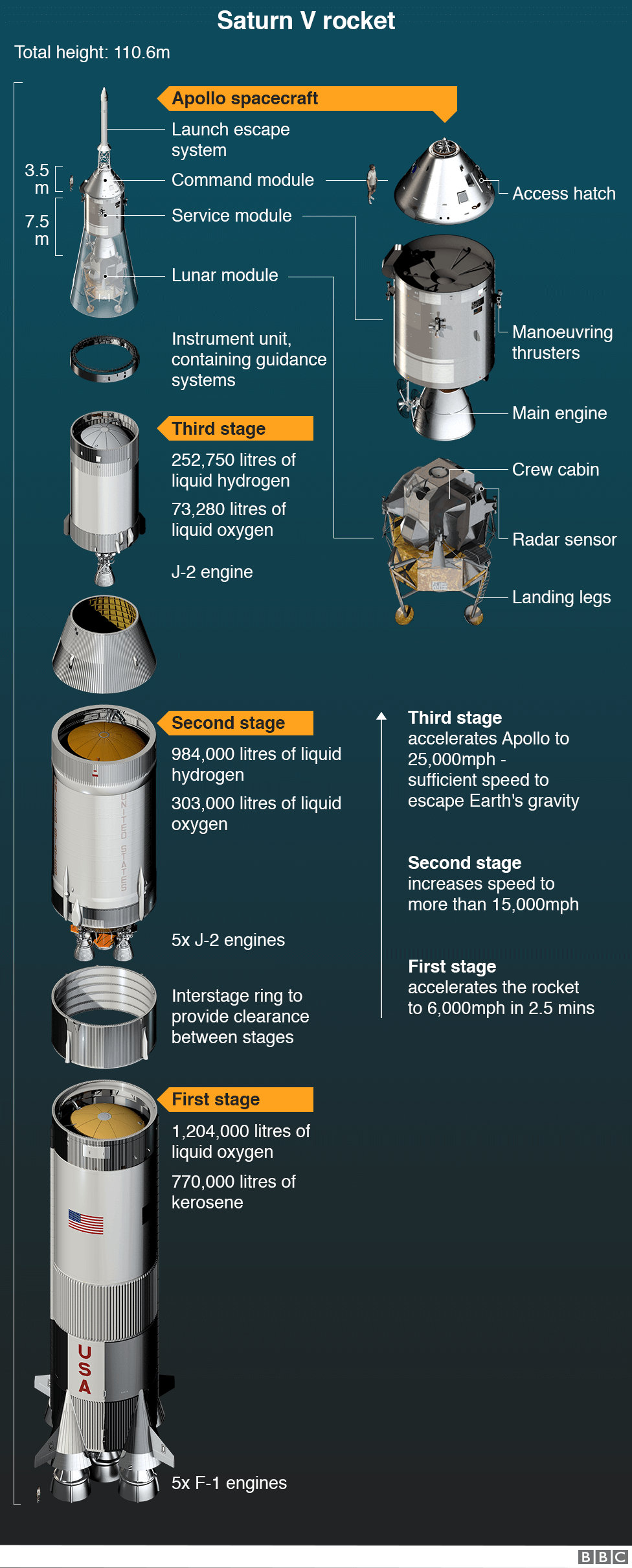

Spacecraft and rockets were essential tools in getting Apollo astronauts to the Moon. The manned Apollo missions were each launched aboard a Saturn V rocket and remains the United States largest and most powerful launch vehicle ever built. The Apollo spacecraft consisted of three components: a command module, a service module, and a lunar module. Together, this technology got Apollo astronauts to the Moon and returned them home safely.

The command module served as the living quarters for the crew for most of the mission"s duration. It is also the only part of the spacecraft which returned to Earth, landing in the ocean where the astronauts where then retrieved by a ship. This particular command module, Columbia, is from the Apollo 11 mission, which was the first Apollo mission to land humans on the Moon.

LM 2 was built for a second unmanned Earth-orbit test flight. Because the test flight of LM 1, named Apollo 5, was so successful, a second mission was deemed unnecessary.

The Apollo lunar module was a two-stage vehicle used to ferry two astronauts from lunar orbit to the lunar surface and back. The upper ascent stage consisted of a pressurized crew compartment, equipment areas, and an ascent rocket engine. The lower descent stage had the landing gear and contained the descent rocket engine and lunar surface experiments. This particular lunar module, LM 2, was used during an unmanned test flight during the Apollo program, and therefore returned to Earth, rather than being purposefully destroyed either in the Earth"s atmosphere or by crashing it into the lunar surface. It has been modified to look like the Apollo 11 lunar module, Eagle.

First used during the Apollo 15 mission, the lunar roving vehicle (LRV), allowed astronauts to travel much father from the lunar module than they could previously. It allowed astronauts to carry larger tools during extra-vehicular activities (EVAs), as well as increased carry capacity. Before the LRV, astronauts had to either carry tools on their person, or in the case of Apollo 14, use mobile equipment transporter which resembled a wheel barrow.

Once on the Moon, astronauts carried out various tasks related to research and experimentation. They collected lunar rock and soil samples to be returned to Earth, and conducted experiments on the Moon, such a measuring heat flow, which were carried as part of the Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP).

Despite the creation of tools like specialized tongs for picking up Moon rocks, or a penetrometer used to penetrate the lunar surface, the Apollo astronauts also carried tools which were very similar to the ones we use regularly on Earth.

The Apollo Lunar Surface Experiment Package (ALSEP) was a collection of scientific instruments stowed on a pallet during transport to the lunar surface. During their first moon walk (EVA), the astronauts deployed the instruments on the lunar surface. Each experiment was electrically connected to the Central Station of the ALSEP. An antenna on the Central Station allowed communication with Earth. The ALSEP experiments varied for each Apollo mission. This particular assembly was used for Earth-based training in EVA procedures by Apollo 16 astronauts.

This experiment is identical to one deployed on the lunar surface as part of the Apollo 14 ALSEP. It was designed to measure the numbers, velocities, and the directions of electrons and protons near the surface of the Moon as well as the ways these measurements change in time. Such data are valuable in the study of solar wind, the magnetosphere of the Earth and low-energy solar cosmic rays. Analysis of the Apollo 14 data revealed important information about all of these phenomena.

The Apollo 11 Command Module, "Columbia," was the living quarters for the three-person crew during most of the first crewed lunar landing mission in July 1969. On July 16, 1969, Neil Armstrong, Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin and Michael Collins were launched from Cape Kennedy atop a Saturn V rocket. This Command Module, no. 107, manufactured by North American Rockwell, was one of three parts of the complete Apollo spacecraft. The other two parts were the Service Module and the Lunar Module, nicknamed "Eagle." The Service Module contained the main spacecraft propulsion system and consumables while the Lunar Module was the two-person craft used by Armstrong and Aldrin to descend to the Moon"s surface on July 20. The Command Module is the only portion of the spacecraft to return to Earth.

It was physically transferred to the Smithsonian in 1971 following a NASA-sponsored tour of American cities. The Apollo CM Columbia has been designated a "Milestone of Flight" by the Museum.

Apollo 11 (July 16–24, 1969) was the American spaceflight that first landed humans on the Moon. Commander Neil Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin landed the Apollo Lunar Module Eagle on July 20, 1969, at 20:17 UTC, and Armstrong became the first person to step onto the Moon"s surface six hours and 39 minutes later, on July 21 at 02:56 UTC. Aldrin joined him 19 minutes later, and they spent about two and a quarter hours together exploring the site they had named Tranquility Base upon landing. Armstrong and Aldrin collected 47.5 pounds (21.5 kg) of lunar material to bring back to Earth as pilot Michael Collins flew the Command Module Columbia in lunar orbit, and were on the Moon"s surface for 21 hours, 36 minutes before lifting off to rejoin Columbia.

Apollo 11 was launched by a Saturn V rocket from Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island, Florida, on July 16 at 13:32 UTC, and it was the fifth crewed mission of NASA"s Apollo program. The Apollo spacecraft had three parts: a command module (CM) with a cabin for the three astronauts, the only part that returned to Earth; a service module (SM), which supported the command module with propulsion, electrical power, oxygen, and water; and a lunar module (LM) that had two stages—a descent stage for landing on the Moon and an ascent stage to place the astronauts back into lunar orbit.

Since the Soviet Union had higher lift capacity launch vehicles, Kennedy chose, from among options presented by NASA, a challenge beyond the capacity of the existing generation of rocketry, so that the US and Soviet Union would be starting from a position of equality. A crewed mission to the Moon would serve this purpose.

In spite of that, the proposed program faced the opposition of many Americans and was dubbed a "moondoggle" by Norbert Wiener, a mathematician at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.Project Apollo.Nikita Khrushchev, the Premier of the Soviet Union in June 1961, he proposed making the Moon landing a joint project, but Khrushchev did not take up the offer.United Nations General Assembly on September 20, 1963.

An early and crucial decision was choosing lunar orbit rendezvous over both direct ascent and Earth orbit rendezvous. A space rendezvous is an orbital maneuver in which two spacecraft navigate through space and meet up. In July 1962 NASA head James Webb announced that lunar orbit rendezvous would be usedApollo spacecraft would have three major parts: a command module (CM) with a cabin for the three astronauts, and the only part that returned to Earth; a service module (SM), which supported the command module with propulsion, electrical power, oxygen, and water; and a lunar module (LM) that had two stages—a descent stage for landing on the Moon, and an ascent stage to place the astronauts back into lunar orbit.Saturn V rocket that was then under development.

Project Apollo was abruptly halted by the Apollo 1 fire on January 27, 1967, in which astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger B. Chaffee died, and the subsequent investigation.Apollo 7 evaluated the command module in Earth orbit,Apollo 8 tested it in lunar orbit.Apollo 9 put the lunar module through its paces in Earth orbit,Apollo 10 conducted a "dress rehearsal" in lunar orbit. By July 1969, all was in readiness for Apollo 11 to take the final step onto the Moon.

The Soviet Union appeared to be winning the Space Race by beating the US to firsts, but its early lead was overtaken by the US Gemini program and Soviet failure to develop the N1 launcher, which would have been comparable to the Saturn V.uncrewed probes. On July 13, three days before Apollo 11"s launch, the Soviet Union launched Luna 15, which reached lunar orbit before Apollo 11. During descent, a malfunction caused Luna 15 to crash in Mare Crisium about two hours before Armstrong and Aldrin took off from the Moon"s surface to begin their voyage home. The Nuffield Radio Astronomy Laboratories radio telescope in England recorded transmissions from Luna 15 during its descent, and these were released in July 2009 for the 40th anniversary of Apollo 11.

The initial crew assignment of Commander Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot (CMP) Jim Lovell, and Lunar Module Pilot (LMP) Buzz Aldrin on the backup crew for Apollo 9 was officially announced on November 20, 1967.Gemini 12. Due to design and manufacturing delays in the LM, Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 swapped prime and backup crews, and Armstrong"s crew became the backup for Apollo 8. Based on the normal crew rotation scheme, Armstrong was then expected to command Apollo 11.

There would be one change. Michael Collins, the CMP on the Apollo 8 crew, began experiencing trouble with his legs. Doctors diagnosed the problem as a bony growth between his fifth and sixth vertebrae, requiring surgery.Fred Haise filled in as backup LMP, and Aldrin as backup CMP for Apollo 8.STS-26 in 1988.

Deke Slayton gave Armstrong the option to replace Aldrin with Lovell, since some thought Aldrin was difficult to work with. Armstrong had no issues working with Aldrin but thought it over for a day before declining. He thought Lovell deserved to command his own mission (eventually Apollo 13).

The Apollo 11 prime crew had none of the close cheerful camaraderie characterized by that of Apollo 12. Instead, they forged an amiable working relationship. Armstrong in particular was notoriously aloof, but Collins, who considered himself a loner, confessed to rebuffing Aldrin"s attempts to create a more personal relationship.

The backup crew consisted of Lovell as Commander, William Anders as CMP, and Haise as LMP. Anders had flown with Lovell on Apollo 8.National Aeronautics and Space Council effective August 1969, and announced he would retire as an astronaut at that time. Ken Mattingly was moved from the support crew into parallel training with Anders as backup CMP in case Apollo 11 was delayed past its intended July launch date, at which point Anders would be unavailable.

By the normal crew rotation in place during Apollo, Lovell, Mattingly, and Haise were scheduled to fly on Apollo 14, but the three of them were bumped to Apollo 13: there was a crew issue for Apollo 13 as none of them except Edgar Mitchell flew in space again. George Mueller rejected the crew and this was the first time an Apollo crew was rejected. To give Shepard more training time, Lovell"s crew were bumped to Apollo 13. Mattingly would later be replaced by Jack Swigert as CMP on Apollo 13.

During Projects Mercury and Gemini, each mission had a prime and a backup crew. For Apollo, a third crew of astronauts was added, known as the support crew. The support crew maintained the flight plan, checklists and mission ground rules, and ensured the prime and backup crews were apprised of changes. They developed procedures, especially those for emergency situations, so these were ready for when the prime and backup crews came to train in the simulators, allowing them to concentrate on practicing and mastering them.Ronald Evans and Bill Pogue.

The capsule communicator (CAPCOM) was an astronaut at the Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas, who was the only person who communicated directly with the flight crew.Charles Duke, Ronald Evans, Bruce McCandless II, James Lovell, William Anders, Ken Mattingly, Fred Haise, Don L. Lind, Owen K. Garriott and Harrison Schmitt.

The Apollo 11 mission emblem was designed by Collins, who wanted a symbol for "peaceful lunar landing by the United States". At Lovell"s suggestion, he chose the bald eagle, the national bird of the United States, as the symbol. Tom Wilson, a simulator instructor, suggested an olive branch in its beak to represent their peaceful mission. Collins added a lunar background with the Earth in the distance. The sunlight in the image was coming from the wrong direction; the shadow should have been in the lower part of the Earth instead of the left. Aldrin, Armstrong and Collins decided the Eagle and the Moon would be in their natural colors, and decided on a blue and gold border. Armstrong was concerned that "eleven" would not be understood by non-English speakers, so they went with "Apollo 11",everyone who had worked toward a lunar landing".

After the crew of Apollo 10 named their spacecraft Charlie Brown and Snoopy, assistant manager for public affairs Julian Scheer wrote to George Low, the Manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office at the MSC, to suggest the Apollo 11 crew be less flippant in naming their craft. The name Snowcone was used for the CM and Haystack was used for the LM in both internal and external communications during early mission planning.

The astronauts had personal preference kits (PPKs), small bags containing personal items of significance they wanted to take with them on the mission.Columbia before launch, and two on Eagle.

Neil Armstrong"s LM PPK contained a piece of wood from the Wright brothers" 1903 "s left propeller and a piece of fabric from its wing,astronaut pin originally given to Slayton by the widows of the Apollo 1 crew. This pin had been intended to be flown on that mission and given to Slayton afterwards, but following the disastrous launch pad fire and subsequent funerals, the widows gave the pin to Slayton. Armstrong took it with him on Apollo 11.

NASA"s Apollo Site Selection Board announced five potential landing sites on February 8, 1968. These were the result of two years" worth of studies based on high-resolution photography of the lunar surface by the five uncrewed probes of the Lunar Orbiter program and information about surface conditions provided by the Surveyor program.

providing the Apollo spacecraft with a free-return trajectory, one that would allow it to coast around the Moon and safely return to Earth without requiring any engine firings should a problem arise on the way to the Moon;

During the first press conference after the Apollo 11 crew was announced, the first question was, "Which one of you gentlemen will be the first man to step onto the lunar surface?"

One of the first versions of the egress checklist had the lunar module pilot exit the spacecraft before the commander, which matched what had been done on Gemini missions,George Mueller told reporters he would be first as well. Aldrin heard that Armstrong would be the first because Armstrong was a civilian, which made Aldrin livid. Aldrin attempted to persuade other lunar module pilots he should be first, but they responded cynically about what they perceived as a lobbying campaign. Attempting to stem interdepartmental conflict, Slayton told Aldrin that Armstrong would be first since he was the commander. The decision was announced in a press conference on April 14, 1969.

For decades, Aldrin believed the final decision was largely driven by the lunar module"s hatch location. Because the astronauts had their spacesuits on and the spacecraft was so small, maneuvering to exit the spacecraft was difficult. The crew tried a simulation in which Aldrin left the spacecraft first, but he damaged the simulator while attempting to egress. While this was enough for mission planners to make their decision, Aldrin and Armstrong were left in the dark on the decision until late spring.

The ascent stage of LM-5 Eagle arrived at the Kennedy Space Center on January 8, 1969, followed by the descent stage four days later, and CSM-107 Columbia on January 23.Eagle and Apollo 10"s LM-4 Snoopy; Eagle had a VHF radio antenna to facilitate communication with the astronauts during their EVA on the lunar surface; a lighter ascent engine; more thermal protection on the landing gear; and a package of scientific experiments known as the Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package (EASEP). The only change in the configuration of the command module was the removal of some insulation from the forward hatch.Operations and Checkout Building to the Vehicle Assembly Building on April 14.

The S-IVB third stage of Saturn V AS-506 had arrived on January 18, followed by the S-II second stage on February 6, S-IC first stage on February 20, and the Saturn V Instrument Unit on February 27. At 12:30 on May 20, the 5,443-tonne (5,357-long-ton; 6,000-short-ton) assembly departed the Vehicle Assembly Building atop the crawler-transporter, bound for Launch Pad 39A, part of Launch Complex 39, while Apollo 10 was still on its way to the Moon. A countdown test commenced on June 26, and concluded on July 2. The launch complex was floodlit on the night of July 15, when the crawler-transporter carried the mobile service structure back to its parking area.liquid hydrogen.ATOLL programming language.

The Apollo 11 Saturn V space vehicle lifts off with Astronauts Neil A. Armstrong, Michael Collins and Edwin E. Aldrin Jr. at 9:32 a.m. EDT July 16, 1969, from Kennedy Space Center"s Launch Complex 39A.

An estimated one million spectators watched the launch of Apollo 11 from the highways and beaches in the vicinity of the launch site. Dignitaries included the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General William Westmoreland, four cabinet members, 19 state governors, 40 mayors, 60 ambassadors and 200 congressmen. Vice President Spiro Agnew viewed the launch with former president Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife Lady Bird Johnson.Richard Nixon viewed the launch from his office in the White House with his NASA liaison officer, Apollo astronaut Frank Borman.

Saturn V AS-506 launched Apollo 11 on July 16, 1969, at 13:32:00 UTC (9:32:00 EDT).roll into its flight azimuth of 72.058°. Full shutdown of the first-stage engines occurred about 2 minutes and 42 seconds into the mission, followed by separation of the S-IC and ignition of the S-II engines. The second stage engines then cut off and separated at about 9 minutes and 8 seconds, allowing the first ignition of the S-IVB engine a few seconds later.

Apollo 11 entered a near-circular Earth orbit at an altitude of 100.4 nautical miles (185.9 km) by 98.9 nautical miles (183.2 km), twelve minutes into its flight. After one and a half orbits, a second ignition of the S-IVB engine pushed the spacecraft onto its trajectory toward the Moon with the trans-lunar injection (TLI) burn at 16:22:13 UTC. About 30 minutes later, with Collins in the left seat and at the controls, the transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver was performed. This involved separating Columbia from the spent S-IVB stage, turning around, and docking with Eagle still attached to the stage. After the LM was extracted, the combined spacecraft headed for the Moon, while the rocket stage flew on a trajectory past the Moon.slingshot effect from passing around the Moon threw it into an orbit around the Sun.

On July 19 at 17:21:50 UTC, Apollo 11 passed behind the Moon and fired its service propulsion engine to enter lunar orbit.Sabine D. The site was selected in part because it had been characterized as relatively flat and smooth by the automated Ranger 8 and Surveyor 5 landers and the Lunar Orbiter mapping spacecraft, and because it was unlikely to present major landing or EVA challenges.

Five minutes into the descent burn, and 6,000 feet (1,800 m) above the surface of the Moon, the LM guidance computer (LGC) distracted the crew with the first of several unexpected 1201 and 1202 program alarms. Inside Mission Control Center, computer engineer Jack Garman told Guidance Officer Steve Bales it was safe to continue the descent, and this was relayed to the crew. The program alarms indicated "executive overflows", meaning the guidance computer could not complete all its tasks in real-time and had to postpone some of them.Margaret Hamilton, the Director of Apollo Flight Computer Programming at the MIT Charles Stark Draper Laboratory later recalled:

To blame the computer for the Apollo 11 problems is like blaming the person who spots a fire and calls the fire department. Actually, the computer was programmed to do more than recognize error conditions. A complete set of recovery programs was incorporated into the software. The software"s action, in this case, was to eliminate lower priority tasks and re-establish the more important ones. The computer, rather than almost forcing an abort, prevented an abort. If the computer hadn"t recognized this problem and taken recovery action, I doubt if Apollo 11 would have been the successful Moon landing it was.

During the mission, the cause was diagnosed as the rendezvous radar switch being in the wrong position, causing the computer to process data from both the rendezvous and landing radars at the same time.Don Eyles concluded in a 2005 Guidance and Control Conference paper that the problem was due to a hardware design bug previously seen during testing of the first uncrewed LM in Apollo 5. Having the rendezvous radar on (so it was warmed up in case of an emergency landing abort) should have been irrelevant to the computer, but an electrical phasing mismatch between two parts of the rendezvous radar system could cause the stationary antenna to appear to the computer as dithering back and forth between two positions, depending upon how the hardware randomly powered up. The extra spurious cycle stealing, as the rendezvous radar updated an involuntary counter, caused the computer alarms.

Eagle landed at 20:17:40 UTC on Sunday July 20 with 216 pounds (98 kg) of usable fuel remaining. Information available to the crew and mission controllers during the landing showed the LM had enough fuel for another 25 seconds of powered flight before an abort without touchdown would have become unsafe,

He then took communion privately. At this time NASA was still fighting a lawsuit brought by atheist Madalyn Murray O"Hair (who had objected to the Apollo 8 crew reading from the Book of Genesis) demanding that their astronauts refrain from broadcasting religious activities while in space. For this reason, Aldrin chose to refrain from directly mentioning taking communion on the Moon. Aldrin was an elder at the Webster Presbyterian Church, and his communion kit was prepared by the pastor of the church, Dean Woodruff. Webster Presbyterian possesses the chalice used on the Moon and commemorates the event each year on the Sunday closest to July 20.

Apollo 11 used slow-scan television (TV) incompatible with broadcast TV, so it was displayed on a special monitor and a conventional TV camera viewed this monitor (thus, a broadcast of a broadcast), significantly reducing the quality of the picture.Goldstone in the United States, but with better fidelity by Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station near Canberra in Australia. Minutes later the feed was switched to the more sensitive Parkes radio telescope in Australia.recordings of the original slow scan source transmission from the lunar surface were likely destroyed during routine magnetic tape re-use at NASA.

Armstrong intended to say "That"s one small step for a man", but the word "a" is not audible in the transmission, and thus was not initially reported by most observers of the live broadcast. When later asked about his quote, Armstrong said he believed he said "for a man", and subsequent printed versions of the quote included the "a" in square brackets. One explanation for the absence may be that his accent caused him to slur the words "for a" together; another is the intermittent nature of the audio and video links to Earth, partly because of storms near Parkes Observatory. A more recent digital analysis of the tape claims to reveal the "a" may have been spoken but obscured by static. Other analysis points to the claims of static and slurring as "face-saving fabrication", and that Armstrong himself later admitted to misspeaking the line.

About seven minutes after stepping onto the Moon"s surface, Armstrong collected a contingency soil sample using a sample bag on a stick. He then folded the bag and tucked it into a pocket on his right thigh. This was to guarantee there would be some lunar soil brought back in case an emergency required the astronauts to abandon the EVA and return to the LM.Hasselblad camera that could be operated hand held or mounted on Armstrong"s Apollo space suit.

They deployed the EASEP, which included a passive seismic experiment package used to measure moonquakes and a retroreflector array used for the lunar laser ranging experiment.Little West Crater while Aldrin collected two core samples. He used the geologist"s hammer to pound in the tubes—the only time the hammer was used on Apollo 11—but was unable to penetrate more than 6 inches (15 cm) deep. The astronauts then collected rock samples using scoops and tongs on extension handles. Many of the surface activities took longer than expected, so they had to stop documenting sample collection halfway through the allotted 34 minutes. Aldrin shoveled 6 kilograms (13 lb) of soil into the box of rocks in order to pack them in tightly.basalt and breccia.armalcolite, tranquillityite, and pyroxferroite. Armalcolite was named after Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins. All have subsequently been found on Earth.

Mission Control used a coded phrase to warn Armstrong his metabolic rates were high, and that he should slow down. He was moving rapidly from task to task as time ran out. As metabolic rates remained generally lower than expected for both astronauts throughout the walk, Mission Control granted the astronauts a 15-minute extension.

Aldrin entered Eagle first. With some difficulty the astronauts lifted film and two sample boxes containing 21.55 kilograms (47.5 lb) of lunar surface material to the LM hatch using a flat cable pulley device called the Lunar Equipment Conveyor (LEC). This proved to be an inefficient tool, and later missions preferred to carry equipment and samples up to the LM by hand.life support, the explorers lightened the ascent stage for the return to lunar orbit by tossing out their PLSS backpacks, lunar overshoes, an empty Hasselblad camera, and other equipment. The hatch was closed again at 05:11:13. They then pressurized the LM and settled down to sleep.

Presidential speech writer William Safire had prepared an In Event of Moon Disaster announcement for Nixon to read in the event the Apollo 11 astronauts were stranded on the Moon.White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman, in which Safire suggested a protocol the administration might follow in reaction to such a disaster.burial at sea. The last line of the prepared text contained an allusion to Rupert Brooke"s World War I poem "The Soldier".

After more than 21+1⁄2 hours on the lunar surface, in addition to the scientific instruments, the astronauts left behind: an Apollo 1 mission patch in memory of astronauts Roger Chaffee, Gus Grissom, and Edward White, who died when their command module caught fire during a test in January 1967; two memorial medals of Soviet cosmonauts Vladimir Komarov and Yuri Gagarin, who died in 1967 and 1968 respectively; a memorial bag containing a gold replica of an olive branch as a traditional symbol of peace; and a silicon message disk carrying the goodwill statements by Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon along with messages from leaders of 73 countries around the world.

One of Collins" first tasks was to identify the lunar module on the ground. To give Collins an idea where to look, Mission Control radioed that they believed the lunar module landed about 4 miles (6.4 km) off target. Each time he passed over the suspected lunar landing site, he tried in vain to find the module. On his first orbits on the back side of the Moon, Collins performed maintenance activities such as dumping excess water produced by the fuel cells and preparing the cabin for Armstrong and Aldrin to return.

Just before he reached the dark side on the third orbit, Mission Control informed Collins there was a problem with the temperature of the coolant. If it became too cold, parts of Columbia might freeze. Mission Control advised him to assume manual control and implement Environmental Control System Malfunction Procedure 17. Instead, Collins flicked the switch on the system from automatic to manual and back to automatic again, and carried on with normal housekeeping chores, while keeping an eye on the temperature. When Columbia came back around to the near side of the Moon again, he was able to report that the problem had been resolved. For the next couple of orbits, he described his time on the back side of the Moon as "relaxing". After Aldrin and Armstrong completed their EVA, Collins slept so he could be rested for the rendezvous. While the flight plan called for Eagle to meet up with Columbia, Collins was prepared for a contingency in which he would fly Columbia down to meet Eagle.

Eagle rendezvoused with Columbia at 21:24 UTC on July 21, and the two docked at 21:35. Eagle"s ascent stage was jettisoned into lunar orbit at 23:41.Apollo 12 flight, it was noted that Eagle was still likely to be orbiting the Moon. Later NASA reports mentioned that Eagle"s orbit had decayed, resulting in it impacting in an "uncertain location" on the lunar surface.

Aldrin added:This has been far more than three men on a mission to the Moon; more, still, than the efforts of a government and industry team; more, even, than the efforts of one nation. We feel that this stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all mankind to explore the unknown ... Personally, in reflecting on the events of the past several days, a verse from Psalms comes to mind. "When I consider the heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the Moon and the stars, which Thou hast ordained; What is man that Thou art mindful of him?"

Armstrong concluded:The responsibility for this flight lies first with history and with the giants of science who have preceded this effort; next with the American people, who have, through their will, indicated their desire; next with four administrations and their Congresses, for implementing that will; and then, with the agency and industry teams that built our spacecraft, the Saturn, the Columbia, the Eagle, and the little EMU, the spacesuit and backpack that was our small spacecraft out on the lunar surface. We would like to give special thanks to all those Americans who built the spacecraft; who did the construction, design, the tests, and put their hearts and all their abilities into those craft. To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all the other people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11.

The aircraft carrier USS Hornet, under the command of Captain Carl J. Seiberlich,LPH USS Princeton, which had recovered Apollo 10 on May 26. Hornet was then at her home port of Long Beach, California.Pearl Harbor on July 5, Hornet embarked the Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King helicopters of HS-4, a unit which specialized in recovery of Apollo spacecraft, specialized divers of UDT Detachment Apollo, a 35-man NASA recovery team, and about 120 media representatives. To make room, most of Hornet"s air wing was left behind in Long Beach. Special recovery equipment was also loaded, including a boilerplate command module used for training.

On July 12, with Apollo 11 still on the launch pad, Hornet departed Pearl Harbor for the recovery area in the central Pacific,Secretary of State William P. Rogers and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger flew to Johnston Atoll on Air Force One, then to the command ship USS Arlington in Marine One. After a night on board, they would fly to Hornet in Marine One for a few hours of ceremonies. On arrival aboard Hornet, the party was greeted by the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Command (CINCPAC), Admiral John S. McCain Jr., and NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine, who flew to Hornet from Pago Pago in one of Hornet"s carrier onboard delivery aircraft.

Weather satellites were not yet common, but US Air Force Captain Hank Brandli had access to top-secret spy satellite images. He realized that a storm front was headed for the Apollo recovery area. Poor visibility which could make locating the capsule difficult, and strong upper-level winds which "would have ripped their parachutes to shreds" according to Brandli, posed a serious threat to the safety of the mission.Fleet Weather Center at Pearl Harbor, who had the required security clearance. On their recommendation, Rear Admiral Donald C. Davis, commander of Manned Spaceflight Recovery Forces, Pacific, advised NASA to change the recovery area, each man risking his career. A new location was selected 215 nautical miles (398 km) northeast.

This altered the flight plan. A different sequence of computer programs was used, one never before attempted. In a conventional entry, trajectory event P64 was followed by P67. For a skip-out re-entry, P65 and P66 were employed to handle the exit and entry parts of the skip. In this case, because they were extending the re-entry but not actually skipping out, P66 was not invoked and instead, P65 led directly to P67. The crew were also warned they would not be in a full-lift (heads-down) attitude when they entered P67.2); the second, to 6.0 standard gravities (59 m/s2).

After touchdown on Hornet at 17:53 UTC, the helicopter was lowered by the elevator into the hangar bay, where the astronauts walked the 30 feet (9.1 m) to the Mobile quarantine facility (MQF), where they would begin the Earth-based portion of their 21 days of quarantine.Apollo 14, before the Moon was proven to be barren of life, and the quarantine process dropped.

The three astronauts spoke before a joint session of Congress on September 16, 1969. They presented two US flags, one to the House of Representatives and the other to the Senate, that they had carried with them to the surface of the Moon.flag of American Samoa on Apollo 11 is on display at the Jean P. Haydon Museum in Pago Pago, the capital of American Samoa.

This celebration began a 38-day world tour that brought the astronauts to 22 foreign countries and included visits with the leaders of many countries.Moon landing with special features in magazines or by issuing Apollo 11 commemorative postage stamps or coins.

Humans walking on the Moon and returning safely to Earth accomplished Kennedy"s goal set eight years earlier. In Mission Control during the Apollo 11 landing, Kennedy"s speech flashed on the screen, followed by the words "TASK ACCOMPLISHED, July 1969".Space Race.

New phrases permeated into the English language. "If they can send a man to the Moon, why can"t they ...?" became a common saying following Apollo 11.

While most people celebrated the accomplishment, disenfranchised Americans saw it as a symbol of the divide in America, evidenced by protesters led by Ralph Abernathy outside of Kennedy Space Center the day before Apollo 11 launched.Thomas Paine met with Abernathy at the occasion, both hoping that the space program can spur progress also in other regards, such as poverty in the US.Gil Scott-Heron called "Whitey on the Moon" (1970) illustrated the racial inequality in the United States that was highlighted by the Space Race.

Twenty percent of the world"s population watched humans walk on the Moon for the first time. While Apollo 11 sparked the interest of the world, the follow-on Apollo missions did not hold the interest of the nation.

After the Apollo 11 mission, officials from the Soviet Union said landing humans on the Moon was dangerous and unnecessary. At the time the Soviet Union was attempting to retrieve lunar samples robotically. The Soviets publicly denied there was a race to the Moon, and indicated they were not making an attempt.Mstislav Keldysh said in July 1969, "We are concentrating wholly on the creation of large satellite systems." It was revealed in 1989 that the Soviets had tried to send people to the Moon, but were unable due to technological difficulties.

Columbia was moved in 2017 to the NASM Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, to be readied for a four-city tour titled Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission. This included Space Center Houston from October 14, 2017, to March 18, 2018, the Saint Louis Science Center from April 14 to September 3, 2018, the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh from September 29, 2018, to February 18, 2019, and its last location at Museum of Flight in Seattle from March 16 to September 2, 2019.Cincinnati Museum Center. The ribbon cutting ceremony was on September 29, 2019.

For 40 years Armstrong"s and Aldrin"s space suits were displayed in the museum"s Apollo to the Moon exhibit,Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center annex near Washington Dulles International Airport in Chantilly, Virginia, where they are on display along with a test lunar module.

The descent stage of the LM Eagle remains on the Moon. In 2009, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) imaged the various Apollo landing sites on the surface of the Moon, for the first time with sufficient resolution to see the descent stages of the lunar modules, scientific instruments, and foot trails made by the astronauts.Eagle ascent stage was not tracked after it was jettisoned, and the lunar gravity field is sufficiently non-uniform to make the orbit of the spacecraft unpredictable after a short time.

In March 2012 a team of specialists financed by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos located the F-1 engines from the S-IC stage that launched Apollo 11 into space. They were found on the Atlantic seabed using advanced sonar scanning.

The main repository for the Apollo Moon rocks is the Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. For safekeeping, there is also a smaller collection stored at White Sands Test Facility near Las Cruces, New Mexico. Most of the rocks are stored in nitrogen to keep them free of moisture. They are handled only indirectly, using special tools. Over 100 research laboratories worldwide conduct studies of the samples; approximately 500 samples are prepared and sent to investigators every year.

In November 1969, Nixon asked NASA to make up about 250 presentation Apollo 11 lunar sample displays for 135 nations, the fifty states of the United States and its possessions, and the United Nations. Each display included Moon dust from Apollo 11 and flags, including the one of the Soviet Union, taken along by Apollo 11. The rice-sized particles were four small pieces of Moon soil weighing about 50 mg and were enveloped in a clear acrylic button about as big as a United States half dollar coin. This acrylic button magnified the grains of lunar dust. Nixon gave the Apollo 11 lunar sample displays as goodwill gifts in 1970.

On July 15, 2009, Life.com released a photo gallery of previously unpublished photos of the astronauts taken by Life photographer Ralph Morse prior to the Apollo 11 launch.John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum set up an Adobe Flash website that rebroadcasts the transmissions of Apollo 11 from launch to landing on the Moon.

It was carried out in a technically brilliant way with risks taken ... that would be inconceivable in the risk-averse world of today ... The Apollo programme is arguably the greatest technical achievement of mankind to date ... nothing since Apollo has come close [to] the excitement that was generated by those astronauts—Armstrong, Aldrin and the 10 others who followed them.

On June 10, 2015, Congressman Bill Posey introduced resolution H.R. 2726 to the 114th session of the United States House of Representatives directing the United States Mint to design and sell commemorative coins in gold, silver and clad for the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. On January 24, 2019, the Mint released the Apollo 11 Fiftieth Anniversary commemorative coins to the public on its website.

The Smithsonian Institute"s National Air and Space Museum and NASA sponsored the "Apollo 50 Festival" on the National Mall in Washington DC. The three day (July 18 to 20, 2019) outdoor festival featured hands-on exhibits and activities, live performances, and speakers such as Adam Savage and NASA scientists.

As part of the festival, a projection of the 363-foot (111 m) tall Saturn V rocket was displayed on the east face of the 555-foot (169 m) tall Washington Monument from July 16 through the 20th from 9:30 pm until 11:30 pm (EDT). The program also included a 17-minute show that combined full-motion video projected on the Washington Monument to recreate the assembly and launch of the Saturn V rocket. The projection was joined by a 40-foot (12 m) wide recreation of the Kennedy Space Center countdown clock and two large video screens showing archival footage to recreate the time leading up to the moon landing. There were three shows per night on July 19–20, with the last show on Saturday, delayed slightly so the portion where Armstrong first set foot on the Moon would happen exactly 50 years to the second after the actual event.

On July 19, 2019, the Google Doodle paid tribute to the Apollo 11 Moon Landing, complete with a link to an animated YouTube video with voiceover by astronaut Michael Collins.

PBS three-night six-hour documentary, directed by Robert Stone, examined the events leading up to the Apollo 11 mission. An accompanying book of the same name was also released.

8 Days: To the Moon and Back, a PBS and BBC Studios 2019 documentary film by Anthony Philipson re-enacting major portions of the Apollo 11 mission using mission audio recordings, new studio footage, NASA and news archives, and computer-generated imagery.

Eric Jones of the Apollo Lunar Surface Journal explains that the indefinite article "a" was intended, whether or not it was said; the intention was to contrast a man (an individual"s action) and mankind (as a species).

In some of the following sources, times are shown in the format hours:minutes:seconds (e.g. 109:24:15), referring to the mission"s Ground Elapsed Time (GET),UTC (000:00:00 GET).

"Apollo 11 Command and Service Module (CSM)". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

"Apollo 11 Lunar Module / EASEP". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Archived from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

Jones, Eric M., ed. (1995). "The First Lunar Landing". Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

Williams, David R. (December 11, 2003). "Apollo Landing Site Coordinates". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. NASA. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

Jones, Eric (April 8, 2018). "One Small Step". Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal. Archived from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

Jones, Eric M., ed. (1995). "One Small Step". Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on August 8, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

Keilen, Eugene (September 19, 1962). ""Visiting Professor" Kennedy Pushes Space Age Spending" (PDF). The Rice Thresher. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

Fishman, Charles. "What You Didn"t Know About the Apollo 11 Mission". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

Madrigal, Alexis C. (September 12, 2012). "Moondoggle: The Forgotten Opposition to the Apollo Program". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

"Address at 18th U.N. General Assembly". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum. September 20, 1963. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

"The Rendezvous That Was Almost Missed: Lunar Orbit Rendezvous and the Apollo Program". NASA Langley Research Center Office of Public Affairs. NASA. December 1992. Archived from the original on December 23, 2020. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

Butler, P. M. (August 29, 1989). Interplanetary Monitoring Platform (PDF). NASA. pp. 1, 11, 134. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2019.

White, H. D.; Lokerson, D. C. (1971). "The Evolution of IMP Spacecraft Mosfet Data Systems". 18 (1): 233–236. Bibcode:1971ITNS...18..233W. doi:10.1109/TNS.1971.4325871. ISSN 0018-9499.

Brown, Jonathan (July 3, 2009). "Recording tracks Russia"s Moon gatecrash attempt". Archived from the original on September 10, 2011. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

Glen E. Swanson, ed. (August 5, 2004). SP-4223: Before This Decade is Out—Personal Reflections on the Apollo Program—Chapter 9—Glynn S. Lunney. NASA. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-16-050139-5. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2019. Apollo 11 flight directors pose for a group photo in the Mission Control Center. Pictured left to right, and the shifts that they served during the mission, are (in front and sitting) Clifford E. Charlesworth (Shift 1), Gerald D. Griffin (Shift 1), Eugene F. Kranz (Shift 2), Milton L. Windler (Shift 4), and Glynn S. Lunney (Shift 3). (NASA Photo S-69-39192.)

Murray, Charles A.; Cox, Catherine Bly (July 1989). Apollo, the race to the moon. Simon & Schuster. pp. 356, 403, 437. ISBN 978-0-671-61101-9. Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

Woods, David; MacTaggart, Ken; O"Brien, Frank (May 18, 2019). "Day 4, part 4: Checking Out Eagle". Apollo Flight Journal. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2019 – via NASA.

Woods, David; MacTaggart, Ken; O"Brien, Frank (May 18, 2019). "Day 3, part 1: Viewing Africa and Breakfast". Apollo Flight Journal. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2019 – via NASA.

Reichhardt, Tony (June 7, 2019). "Twenty People Who Made Apollo Happen". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

"Kit, Pilot"s Personal Preference, Apollo 11". Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

Woods, W. David; MacTaggart, Kenneth D.; O"Brien, Frank (June 6, 2019). "Day 1, Part 1: Launch". Apollo Flight Journal. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved October 11, 2018 – via NASA.

Woods, W. David; MacTaggart, Kenneth D.; O"Brien, Frank (February 10, 2017). "Day 4, part 1: Entering Lunar Orbit". Apollo Flight Journal. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2019 – via NASA.

"Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Mission" (PDF) (Press kit). Washington, D.C.: NASA. July 6, 1969. Release No: 69-83K. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 11, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

Martin, Fred H. (July 1994). "Apollo 11: 25 Years Later". Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on May 27, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

Jones, Eric M., ed. (1995). "Post-landing Activities". Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

Jones, Eric M.; Glover, Ken, eds. (1995). "First Steps". Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on October 9, 2006. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

Canright, Shelley, ed. (July 15, 2004). "Apollo Moon Landing—35th Anniversary". NASA Education. NASA. Archived from the original on July 4, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013. Includes the "a" article as intended.

"Exhibit: Apollo 11 and Nixon". American Originals. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration. March 1996. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2008.

"Richard Nixon: Telephone Conversation With the Apollo 11 Astronauts on the Moon". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2018.

"Apollo 11 Astronauts Talk With Richard Nixon From the Surface of the Moon - AT&T Archives". AT&T Tech Channel. July 20, 2012. Archived from the original on May 22, 2021. Retrieved December 5, 2020 – via YouTube.

Jones, Eric M., ed. (1995). "EASEP Deployment and Closeout". Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on February 25, 2014. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

University of Western Australia (January 17, 2012). "Moon-walk mineral discovered in Western Australia". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on November 11, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

Jones, Eric M., ed. (1995). "Trying to Rest". Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal. NASA. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

"Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages" (PDF) (Press release). Washington, D.C.: NASA. July 13, 1969. Release No: 69-83F. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 3, 2019. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

Rodriguez, Rachel (July 20, 2009). "The 10-year-old who helped Apollo 11, 40 years later". CNN. Archived from the original on January 26, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2011.

"Press Kit—Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Mission" (PDF). NASA. July 6, 1969. p. 57. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 11, 2021. Retrieved October 11, 2018.

Woods, W. David; MacTaggart, Kenneth D.; O"Brien, Frank. "Day 9: Re-entry and Splashdown". Apollo Flight Journal. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2018 – via NASA.

US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "SMG Weather History—Apollo Program". www.weather.gov. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

""They would get killed": The weather forecast that saved Apollo 11". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2019.

"Remarks to Apollo 11 Astronauts Aboard the U.S.S. Hornet Following Completion of Their Lunar Mission". The American Presidency Project. UC Santa Barbara. July 24, 1969. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2018.

Extra-Terrestrial Exposure, 34 Federal Register 11975 (July 16, 1969), codified at Federal Aviation Regulation pt. 1200 Archived May 22, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

"Richard Nixon: Remarks at a Dinner in Los Angeles Honoring the Apollo 11 Astronauts". The American Presidency Project. August 13, 1969. Archived from the original on May 14, 2020. Retrieved October 24, 2017.

"The Apollo 11 Crew Members Appear Before a Joint Meeting of Congress". United States Ho

8613371530291

8613371530291