apollo 11 mission parts brands

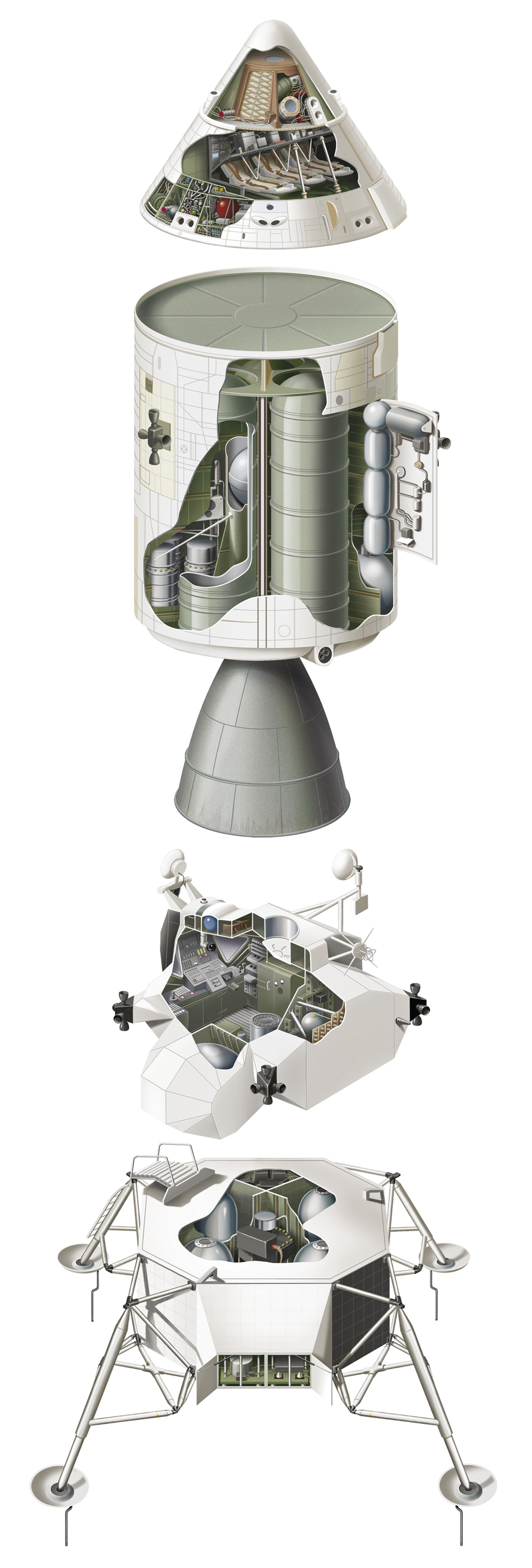

The Apollo Lunar Module, or "LEM" for short, was a highly specialized spacecraft built by Grumman Aircraft Engineering which was designed to land on the lunar surface and return the astronauts to the Command Module in lunar orbit for their trip back to Earth.

At the time, very little about the actual moon spacecraft itself was baked. When compared to the Saturn V rocket itself, it was the least developed part of the entire Apollo system in terms of concept and planning. Additionally, at the time, very few aeronautics contractors knew anything about building actual spacecraft, let alone something that could land on the moon and bring the astronauts home.

Nobody at Grumman had any experience with spacecraft, so this was entirely new territory for the company. However, the Grumman engineers working on the Apollo proposal response had read some early papers by NASA engineers Tom Dolan and John Houbolt who had proposed what is now known as a Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR) mission profile.

LOR was one of three mission profiles considered for the moon landing and was not the front runner for consideration. The others were Earth Orbit Rendezvous and Direct Ascent, the latter of which was the initial candidate.

A "Buck Rogers" style for Direct Ascent as shown in many early Science Fiction movies of the period would have been too expensive and very difficult to engineer within the schedule-driven constraints of the Apollo Program. The EOR profile had its merits, but once LOR had been proven as viable, it was chosen as the mission profile for the landing.

The final design iteration, integrating hundreds of significant design alterations went into production in April of 1963. The first LM was flight tested in Earth orbit on January 22, 1968, aboard the Apollo 5 mission, and the first actual lunar descent test occurred during Apollo 10 in May of 1969, only two months before Apollo 11.

After the Apollo program, Grumman resumed its work on fighter aircraft for the Navy, such as the F-14 Tomcat multi-role interceptor and the E-2 Hawkeye all-weather Airborne Early Warning aircraft which continues to be refined and used by the Navy to this very day.

Reading about NASA rockets, lunar modules, and space shuttles is cool, but there’s nothing like seeing all that stuff with your own eyes in a museum. But what if you didn’t have to go to a museum to see incredible specimens from the space program? What if you could actually own a tiny piece of it, all for yourself? Well, thanks to the folks at Mini Museum, you don’t have to be rich to have your own personal collection of rare historical artifacts. Ever wanted to own a piece of NASA"s Apollo 11 spacecraft, or maybe the Space Shuttle Columbia? Well, now you can, and for less than the cost of a decent pair of sneakers.Mini Museum

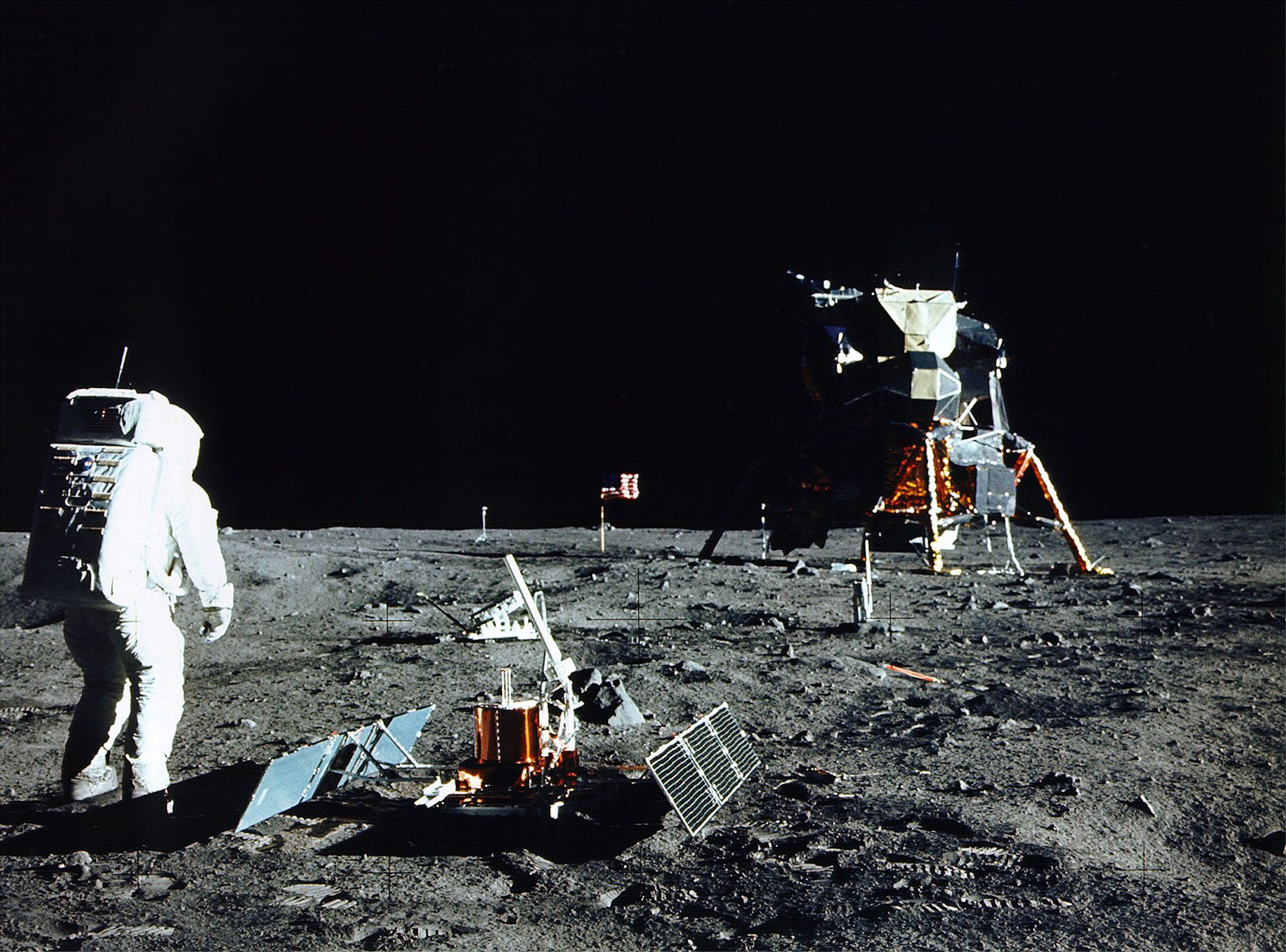

Without a doubt, the crown jewel of Mini Museum’s space collection is the fragment of mission-flown kapton foil from Apollo 11. The section of kapton foil from which these specimens were obtained provided thermal insulation for NASA"s Apollo 11 Command Module, which orbited the Moon on July 20, 1969, as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans ever to land on the surface. This same Command Module then safely transported Armstrong, Aldrin, and pilot Michael Collins back to Earth, where it splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969.

The kapton foil specimen measures approximately 1mm x 1mm and is enclosed in an acrylic cube with a magnifying lid for easy viewing. It comes with a certificate of authenticity, as well as an information card that features images and details from NASA"s Apollo 11 mission.Mini Museum

The Space Shuttle Columbia may not be as famous as the Apollo 11 Command Module, but space buffs certainly understand its historical significance. It was the world’s first ever reusable orbital spacecraft. Now you can own a fragment of mission-flown High-Temperature Reusable Surface Insulation (HRSI), the black silica tiles that protected 90 percent of the spacecraft from extreme re-entry temperatures in excess of 2300 degrees Fahrenheit. The sample measures 4-5mm and is encased in an acrylic specimen jars. It was removed from Columbia following its 7th mission in 1986.Mini Museum

This specimen comes from a mission-flown Space Shuttle nose landing gear tire that was removed from service after Columbia"s 13th mission in 1992. It’s encased in an acrylic specimen jar and housed in a 4" x 3" x 1" glass-topped riker box, and comes with a small information card.

Futurism fans: To create this content, a non-editorial team worked with an affiliate partner. We may collect a small commission on items purchased through this page. This post does not necessarily reflect the views or the endorsement of the Futurism.com editorial staff.

When the Apollo 11 spaceflight departed the Kennedy Space Center on July 16, 1969, it was carrying three astronauts, mankind’s aspirations to finally land on the Moon, and sophisticated equipment that made it all possible. Prior to the historic spaceflight, NASA contracted several companies to build the Saturn V launch vehicle, the Apollo spacecraft that landed on the Moon on July 20, and the Apollo ground control center in Houston. The Dallas based Texas Instruments was one of the subcontractors that supplied parts for all three components of the Apollo 11 mission.

performance of the equipment in Apollo 11,” while holding one of the switches on the control panel of the command module -the capsule that brought the astronauts back to Earth. The switch, TI World proudly pointed out, had been produced by TI’s Control Products division in Attleboro, MA, one of a total of approximately 800 switches required by the space mission. Hundreds of TI’s small signal transistors, silicon and germanium power transistors, computer diodes,, miniature thermostats worked without a hitch to ensure the success of the spaceflight and Moon landing. While it didn’t actually go to the Moon or even outside of Dallas, the data signal conditioner in the image is an example of an integrated circuit similar to the luckier ones that were selected for space travel.

Data and image recording devices built using TI components are essential in the recording and transmission of information taken by the space probes Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, which were launched in 1977, and have since traveled beyond the known planets and into the interstellar space. The Hubble Space Telescope pictured here uses TI built imaging chips.

Falling back from the moon at almost seven miles a second, the crew of Apollo 11 took it in turns to broadcast their thoughts about what their mission meant. Buzz Aldrin spoke not just of it being three men on a mission to the moon, but of their flight symbolising the insatiable curiosity of mankind to explore the unknown. Mike Collins talked about the complexity of the Saturn V and the blood, sweat and tears it had taken to build. And Neil Armstrong thanked the Americans who had put their hearts and all their abilities into building the equipment and machinery that had made the journey possible.

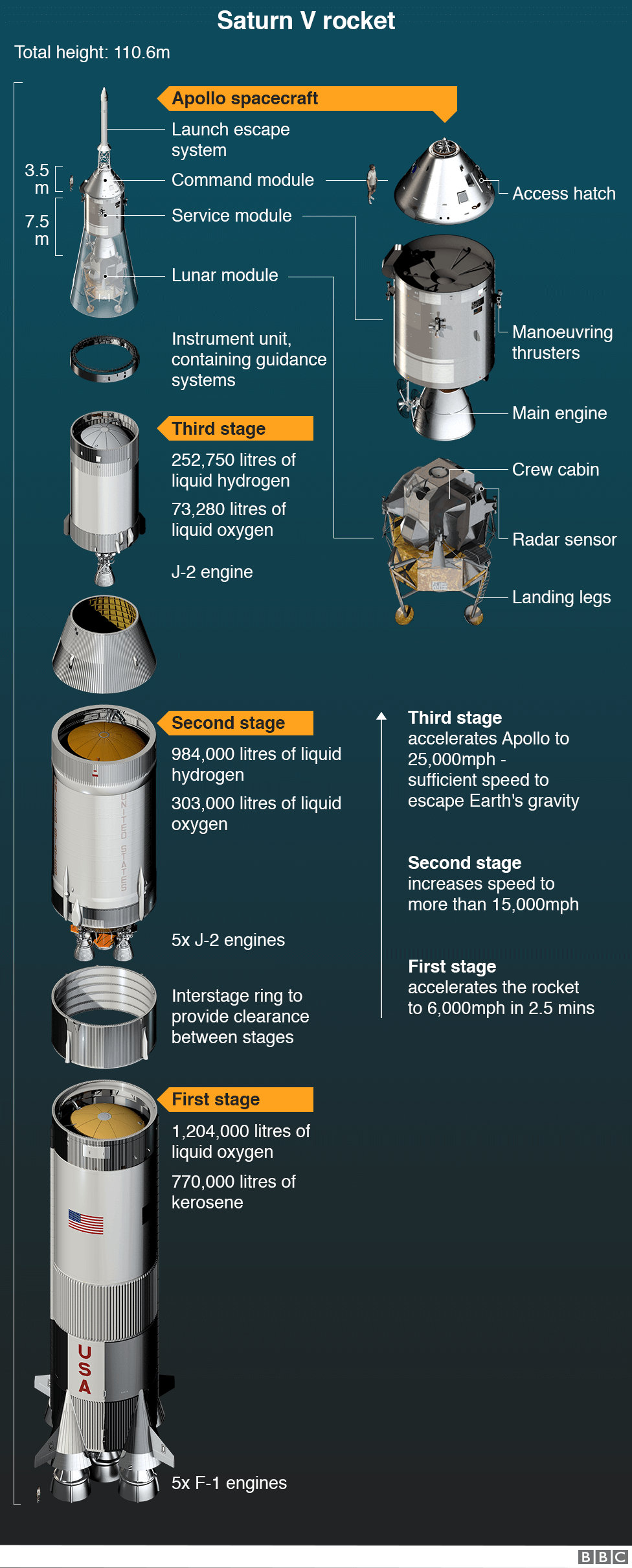

Many of these people had never worked in the aerospace industry, and none had worked before on machines designed to transport humans to another world. Overnight, as their companies won Apollo contracts, their vocations suddenly took on a greater purpose. Achieving technical miracles and overcoming bureaucratic battles, daunting setbacks and tragedies, the single "moonship" they built for the Apollo missions was effectively six individual spacecraft designed and built by five different companies. From the three separate rocket stages built by Boeing, North American Aviation and McDonnell Douglas, to the command, service and lunar modules, built by the Grumman Corporation and North American Aviation again, around five-and-a-half million parts were manufactured for each mission; often by a host of sub-contractors working for these main Apollo companies.

The near impossible task of managing this vast pyramid of people across America fell to the Apollo programme manager George Müller and, in a stroke of genius, he called upon the astronauts themselves for help; each national hero would make personal visits to the factories making all these parts. It was a crucial reminder to the workers that a single technical glitch could kill a man they had personally met. And it compelled each of them to devote their lives to Apollo for the best part of a decade.

During each flight, the colossal workforce would be on call - connected through their line managers - to a series of system support rooms in Houston which in turn fed their advice to one of 20 men in the main mission operations control room known to everyone as MOCR. Right at the top of the pyramid, inside this nerve centre, was one man in charge of each mission and his code name was Flight. For Apollo 11"s landing it was the turn of 36-year-old former fighter pilot, Gene Kranz.

An accomplishment of this immensity had transcended nationhood. Such global unity was something that no peacemaker, politician or prophet had ever quite achieved. But 400,000 engineers with a promise to keep to a president had done it and Nasa knew it. On the plaque fixed to the legs of their machine they had written the words: "We came in peace, for all mankind."Christopher Riley is the author of the new Haynes guide: Apollo 11 - an owner"s workshop manual. He curates the online Apollo film archive at Footagevault.com. His video commentaries about the Apollo mission are at theguardian.com/apollo11

As the astronauts of the Apollo 11 mission prepared to board their spacecraft, the support crew that aided their final preparations wore suits with "ILC Industries" stitched in large block lettering across the back.

As the 50th anniversary nears, NASA"s most recent efforts to bring man back to the moon are in question but the two Delaware companies that made the Apollo 11 mission possible are still making history.

Prior to the mission, Armstrong, Aldrin and Michael Collins, the third member of the Apollo 11 crew, made trips to ILC Dover"s Frederica headquarters to be fit for and test the suits. The suits were fully custom-built for each astronaut.

Two years into ILC"s tenure as NASA"s space suit provider, three astronauts died in a fire during a training exercise for the first Apollo mission. The deaths prompted ILC to completely reconfigure its spacesuit design.

"Each layer of material contributed something different for the overall performance and it was really the total suit coming together that made the mission possible," Norton said.

Since 2017, the agency has been working on the Artemis program — named after the twin sister of the Greek mythological figure Apollo. The effort requires a custom-built Space Launch System rocket, a platform orbiting the moon known as "Gateway" and a lunar lander system to take people to the surface.

The company has varied in size throughout its existence — peaking around 1,000 employees during the lead-up to Apollo 11 and dipping near 25 employees after the Apollo missions — but has long been at the forefront of innovation.

In 1977, ILC Dover won the contract to build suits for the space shuttle, which revived the company. Instead of being individually tailored, the new suits were made of interchangeable parts. The technology is the basis for the suits used today.

The spacesuit business, however, will forever be ILC Dover"s calling card. The company has produced more than 300 space suits. Each Apollo mission alone required 15 suits, three for each member of the first-string crew and two for each of their backups.

"They were and are nowhere near the size of DuPont, but they end up becoming the private contractor for the Apollo," said Clawson, the Hagley historian. "It’s fascinating to me how such a small company like that can have such a large affect."

Like Armstrong, Apollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objectsrecognizes the significance and power of artifacts. Tangible, real objects can connect the past to our present. Fifty years from the first lunar landing, the 50 objects in this book let us revisit a remarkable moment in American history, when grand ambitions overcame grand obstacles, and allow us to not only understand the moment anew but to make it part of our lives. They help tell the full story of spaceflight by revealing the tangle of technological, political, cultural, and social dimensions of the Apollo missions.

The material legacy of Apollo is immense. From capsules to space suits to the ephemera of life aboard a spacecraft, the Smithsonian Institution national collection comprises thousands of artifacts. This excerpt is from a carefully curated selection of 50 of these objects, which reveal how Project Apollo touched people’s lives, both within the space program and around the world.

American spacecraft were designed to land in the ocean. But slowing the capsule down proved challenging, even with highly engineered parachutes. The gaps in the ribbon, ring-sail main parachutes used by Apollo 16, offered greater stability at high speeds.

Published in time for the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing, this 104-page volume packed with photos includes the 25 most dramatic moments of the Apollo program, the extraordinary people who made it possible, and how a new generation of explorers plans to return to the moon.

In the cramped confines of the command module, Apollo 11’s astronauts frequently found it necessary to use whatever writing surface was available to take notes. Often, this meant they would turn to the walls of the craft itself. Command module pilot Michael Collins penned notes representing coordinates on a lunar surface map, relayed to him from Mission Control, as he attempted to locate his crewmates’ landing site from orbit. One later note was a tribute: Collins crawled back into Columbia while aboard the USS Hornet to inscribe a message (above) on the navigational system reading “Spacecraft 107—alias Apollo 11—alias Columbia. The best ship to come down the line. God Bless Her. Michael Collins, CMP.”

Boeing Aerospace designed the lunar roving vehicle (LRV) to extend the astronauts’ range; with the vehicle, crews could drive for 40 miles at a speed of up to 11 mph. Deployment of the vehicle took roughly 11 minutes, with an additional six minutes for navigational alignment and other checks. Apollo 15 astronaut Dave Scott compared it to deploying an “elaborate drawbridge.” Engineers constructed the LRV wheels from a hand-woven mesh made of zinc-coated piano wire, which is lighter and more durable than inflated rubber tires. Scott would later describe the LRV ride as “a cross between a bucking bronco and a small boat in a heavy swell.” The wheel pictured here is a spare from an LRV.

In July 1969, 94 percent of American households tuned their television sets to coverage of Apollo 11. Of these 53 million homes, the vast majority—including the sets at the White House—set their dials to watch news anchor Walter Cronkite on CBS. As the Saturn V rocket lifted off from Cape Canaveral, the usually composed Cronkite spontaneously exclaimed, “Go, baby, go!” Cronkite stayed on air for 27 of the 32 hours of continuous CBS coverage, detailing each stage of the Apollo 11 mission. Because much of the flight was out of sight of film cameras, Cronkite used a small-scale model to explain various stages of the mission.

When the Eagle lunar module touched down in the lunar soil, Cronkite could only cry, “Oh, boy!” before asking retired Apollo 7 astronaut Walter Schirra to say something because he could not. He quickly recovered, however, grasping the moment’s extraordinary significance: “Isn’t this something! 240,000 miles out there on the moon and we’re seeing this [on television].”

“Things which were fun a couple days ago, like shaving in weightlessness, now seem to be a nuisance,” lamented Michael Collins. Nine days into Apollo 11’s flight, inside a spacecraft that had become increasingly smelly and messy, lunar exploration had lost some of its luster.

The first human spaceflight missions were brief, lasting for hours instead of days. On these short flights, concerns about personal hygiene—such as brushing teeth and shaving—were irrelevant. But as NASA started planning for longer durations, the agency faced questions about how to maintain the astronauts’ health in space. Though shaving and other small rituals helped the astronauts maintain a sense of comfort and cleanliness en route to and from the moon, they also drew a sharp contrast with the counterculture movement of late 1960s America. This small razor and its accompanying shaving cream remind us how grooming sometimes represents more than just a style preference.

Michael Collins described simulation as the “heart and soul of NASA.” Simulator supervisors (affectionately known as “Sim Sups”) and their teams of instructors developed a clever series of challenging yet believable malfunctions to challenge Apollo flight crews to respond correctly in real-time situations. This highly realistic training was aimed at both the astronauts who would fly the missions and the flight controllers who would monitor spacecraft telemetry and assure that mission operations were conducted safely. Above is the control panel of the Apollo Mission Simulator, used to test the astronauts’ response to both routine and extreme events.

Apollo astronauts spent hundreds of hours training in these simulators in the months leading up to their missions. During each of the lunar missions, the astronauts inevitably compared the real experience of flying to the moon to the virtual experience that they had encountered during training. The phrase “just like the simulator” can be found in the transcripts from every Apollo mission.

The mission simulators helped save the flight crew of Apollo 13 after an explosion disabled all major spacecraft functions. On the ground, as teams of astronauts, simulator instructors, and flight controllers developed the intricate procedures to operate the crippled spacecraft, the Apollo Mission Simulators worked around the clock to validate each corrective action. These included the complex procedures to power up the dormant Apollo command module just prior to reentry into Earth’s atmosphere, a scenario that had never been contemplated by even the most devious simulation supervisors. The result was the safe return of Apollo 13 back to Earth, what some have called NASA’s “finest hour.”

Largely prepared by the astronauts themselves, checklists provided necessary step-by-step and switch-by-switch procedures. Detailed instructions also included reminders like when to wash their hands or that they should remove watches from pressure suits before they were stowed. Astronaut Michael Collins used the checklist above on board Apollo 11 in July 1969. Its 216 pages are divided into 15 “chapters” or sections: reference data, guidance and navigation computer, navigation, pre-thrust, thrusting, alignments, targeting, extending verbs (for display and keyboard), stabilization and control system general actions, systems management, lunar module interface, contingency extravehicular activity, lunar-orbit insertion aborts, flight emergency, and crew logs. A Velcro lining allowed it to be stuck in a number of locations around the spacecraft. The paper is fireproof, a provision put into place after the Apollo 1 tragedy.

Apollo 16 was the first to carry a small astronomical telescope. Called the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph, it was the creation of George R. Carruthers and his team at the Naval Research Laboratory. Carruthers’ main goal was to get a first glimpse of what the universe looked like in the high-energy far ultraviolet region of the spectrum, which astronomers suspected held many answers to how stars and galaxies form. Astronauts on the moon could not see anything fainter than Earth in the sky because their eyes had to be protected by dense visors. So Carruthers designed the instrument to be easily handled. During three extravehicular activities, the astronauts photographed some 11 regions of the sky, including Earth. They captured over 500 stars, some nebulae and galaxies. The telescope still sits on the moon; only the film was returned to Earth. In 1981, two engineering models were transferred to the Museum; the one shown here was restored in 1992.

Adapted fromApollo to the Moon: A History in 50 Objects, by Teasel Muir-Harmony (Smithsonian Institution and National Geographic, 2018). Printed with permission of the publisher.

As satellites keep advancing, they change the technology landscape on Earth, from improving the GPS in your phone to providing first-time broadband to parts of the developing world. When the James Webb Space Telescope launches in 2021, it will allow us to study every phase of cosmic history. We may not be the scientists who will be studying the telescope’s findings, but we’re the scientists who have researched and developed materials enabling them to do so. In the James Webb there are two key materials that DuPont invented and manufactures: DuPont™ Kapton® and Kevlar® fiber.

As we remember Apollo 11, we salute the pioneers of space, along with the thousands of people and hundreds of companies and organizations who have and continue to work to advance innovation and protect those who journey there.

To do that, several companies either opened or expanded operations in Central Florida. So the moon mission brought companies such as Martin Marietta, Grumman and Lockheed into the forefront of the region’s economy.

“It improved transportation,” Handberg said. “A lot of people decided to live in Central Florida and commute to the Cape during Apollo and later the shuttle.”

That growth was only natural in an area watching a new industry develop, said Charlie Mars, who was NASA’s program chief for the Apollo’s lunar module.

As the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission to the moon approaches, here is a look back at some of the companies that came here to support the iconic program.

Martin Co. merged with American Marietta Corp. in 1961 to become Martin Marietta, which built the Viking Mars Lander. That vehicle became the first to touch down on the Red Planet and successfully executed its mission in 1976. With its Central Florida location, Marietta competed - and ultimately lost out to Grumman - for the lunar lander.

Boeing, along with firms like McDonnell Douglas and Rockwell International that it eventually merged with, built most of the major components of the Apollo spacecraft, including all three stages of its Saturn V rocket.

Boeing sent a lunar orbiter to take pictures of the moon’s surface ahead of the first landing mission. Boeing last month announced that it would relocate its space and launch headquarters to the Space Coast.

Harris Corp.’s presence in Melbourne predates the Apollo program. However, it landed several contracts for the mission, primarily for communications gear that allowed astronauts to contact ground control from the moon.

The propulsion, escape and pitch control systems for the Apollo spacecraft were built and designed by Lockheed Propulsion Co., shortly before the company built Walt Disney World’s first monorail system in 1970. Today, Lockheed Martin employs 8,000 workers in Central Florida and expanded its workforce at its Cape Canaveral site in 2015 to support a missile contract with the U.S. Navy.

Aerojet was a predecessor of what is now Aerojet Rocketdyne and created the solid fuel technology used in Apollo’s Saturn V first stages. In 1963, the company landed $3 million from the U.S. Air Force to build a manufacturing and testing site in Homestead. When the company designed a rocket motor, it was transported by barge to Cape Canaveral.

Grumman Corp. first arrived in Central Florida to support Apollo in the 1960s. The company, now known as Northrop Grumman, built the lunar lander that ferried astronauts to the moon’s surface 50 years ago. That deal was valued at $350 million when it was first awarded.

The lander became what some experts have called the most reliable component of the Apollo missions. About three years ago, Grumman announced it would expand its Space Coast facilities to accommodate nearly 2,000 new employees at Orlando Melbourne International Airport after landing a contract to build the U.S. Air Force’s next-generation bomber.

This story is part of the Orlando Sentinel’s “Countdown to Apollo 11: The First Moon Landing” – 30 days of stories leading up to 50th anniversary of the historic first steps on moon on July 20, 1969. More stories, photos and videos atOrlandoSentinel.com/Apollo11.

Velcro Companies, which made the hook and loop fasteners that astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins used on their 1969 Apollo 11 mission, commissioned a new cover of the rock song "Walking on the Moon" to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the historic moonwalk.

In the video, Nicassio and three other band members wear Apollo Mission Control-inspired outfits — white button-down shirts and skinny ties — while Sarah Blackwood dons a costume spacesuit. Velcro Brand One-Wrap straps, Industrial Strength tapes and Easy Hang straps are used to attach and detach a ukulele, fill the sky with glowing stars and enable Blackwood to perform a spacewalk, of sorts.

On July 16, 1969, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins lifted off inside an Apollo spacecraft outfitted with Velcro hook and loop fasteners to keep their checklists in place, their stowage bags closed and their freeze-dried food packs from floating away. They even launched with extra Velcro pieces to use as needed.

"So we obviously have to hold these in place in zero g, so we make use of the Velcro patches on the back and on the table so we can attach these down here," explained Aldrin, describing the data cue cards used on board the lunar module "Eagle," during a TV broadcast on the third day of the mission.

Velcro Companies worked with NASA to develop a range of hook and loop fasteners that met the needs of the Apollo moon missions. Velcro Brand products are still used on NASA spaceflights today aboard the International Space Station.

Velcro fasteners that were flown to the moon can be seen among the Apollo 11 artifacts displayed by the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, including Armstrong"s spacesuit, which is returning to exhibit after 13 years off display on Tuesday (July 16).

"Walking on the Moon" was originally recorded by the band The Police in 1979. The music video for that version was filmed at NASA"s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, with band members Sting, Andy Summers and Stewart Copeland performing next to the display of a retired Saturn V rocket. The video also features archival film clips from the Apollo 11 mission.

"There are other brands that are celebrating the 50th anniversary, but I think few have the legacy and deep connection we do to the space program, to Apollo 11 and to NASA," said Woodruff.

A Lockheed Martin heritage company—the Lockheed Propulsion Company in Mentone, California—designed and built the solid propellant launch escape system (LES) and the pitch control motor for Apollo 11. The LES was designed to carry the crew safely away from the launch vehicle if an emergency occurred. When activated, the command module would separate from the service module and the LES would fire a solid fuel rocket connected to the top of the command module. A canard system would direct the command module away from the launch vehicle.

There were dozens of other Apollo program subcontractors in the state. Many were small machine shops that turned out thousands of small parts ---- a few of which are still on the Moon.

The vast majority of the gear built for the Apollo mission never made it to the moon, according to Leighton Lee III, whose company, The Lee Co., of Westbrook, built thousands of tiny fluid flow management devices such as plugs and nozzles for the space program.

"The little subcontractors that built these parts always had the best, most-experienced machinist on the shop floor do the work," Lee said. "This was not easy. High-temperature metals are not easy to machine, and this was the age before there was such a thing as CAD/CAM."

He said much of Apollo was "first-of-a-kind" technology. A nautical engineer, for example, has some 8,000 years of shipbuilding tradition from which to draw.

The contracts for the parts were accompanied by the motivational statement: "For use in manned space flight. Materials, manufacturing and workmanship of highest quality standards are essential to astronaut safety."

"There were, perhaps, 100,000 contractors and subcontractors across the U.S. involved in the project," said Deborah Douglas, curator of the MIT Museum in Cambridge, Mass., which has an extensive collection of gear involved with the Apollo guidance systems.

"The parts needed to work not just because the astronauts" lives were at stake, but also because they were also demonstrating the nation"s technological prowess during the Cold War," she said.

Begin with the fact that over the course of NASA’s entire 61-year history, it has never not been part of a public-private partnership. The only branding on the side of the space agency’s rockets and spacecraft may have been an American flag and the words “United States of America,” but if all of the companies that actually built the machines had been able to slap their decals on the ships too, there would have been no room for windows. The Apollo program alone had up to a dozen prime contractors, including North American Aviation, Grumman Corp., Rocketdyne, General Motors, IBM, Douglas Aircraft and even General Motors. Those contractors portioned out the work to so many sub-contractors in so many states around the country that, in the end, an estimated 400,000 people—more than the modern-day population of Cleveland—could say they had a hand in putting Americans on the moon.

The only thing that distinguishes the way the business was conducted then from the way it’s done now is that back in the Apollo era, it was essentially work for hire. NASA would tell the companies exactly what it wanted and the companies would deliver—a little like sketching your own house and then hiring an architect and construction company to build it to your plans.

In case the private-public model behind all of these partnerships was missed, the NASA announcement even adopted the sometimes-tortured language of business: “NASA’s proven experience and unique facilities are helping commercial companies mature their technologies at a competitive pace,” said Jim Reuter, associate administrator of NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate, in a July 30 statement.

None of that is necessarily bad. One of the reasons the lunar program stopped with Apollo is that the old model—a money spigot turned on full as the government paid the entire $24 billion tab ($168 billion in 2019 dollars)—was not sustainable. Better to spread the cost — and the for-profit rewards — among a lot of players.

The problem is that the risks are spread too. The old NASA could withstand setbacks and even disasters like the Apollo 1 fire that killed three astronauts in 1967 because it had no shareholders or investors to keep happy. Businesses are different—sensitive to markets, wary of loss. Those x-factors may make the 2024 deadline harder to meet than the space agency realizes. Either way, it’s likely that whenever America gets back to the moon, a lot of the commercial partners along for the ride now will eventually be left behind.

Inside the Mission Operations Control Room — a freezing-cold space in Houston that smelled like coffee and so much tobacco that a cloud of smoke would draft out when the door opened — that dust meant the landing was no longer theoretical. It was going to happen.

Fifty years later, Duke says he found it “easier” to be the one actually landing a spacecraft on the moon — which he did during Apollo 16 in 1972 — than to monitor this one from Mission Control down on Earth. “I was much more confident and relaxed” in space. “You’re looking out, seeing it, feeling the spacecraft as it maneuvers, [rather] than looking at charts and lines on a computer screen.”

As people around the world began to celebrate, the men in Mission Control knew their work wasn’t yet done. The 35-year-old flight director Gene Kranz, whom TIME described as “a crew-cut and clip-voiced former test pilot,” started to get annoyed by the whooping and hollering of the VIPs in the viewing room behind him. “They start cheering and stomping their feet, and that sound seeps into the room at a time when we have to concentrate,” he says. “I get sort of angry. I sort of yelled at everybody to settle down.” He even broke his pencil and it flew up in the air. The crew still had to do the post-landing checklist.

After getting the clear that it was safe to stay, Neil Armstrong climbed down the ladder of the lunar module and spoke his famous words. Pete Conrad, who would become the third man to walk on the moon during Apollo 12, had come to watch and remarked that it was “just like Armstrong to say something profound like that,” remembers Jerry Bostick, who back then was the 30-year-old leader of a team of flight controllers in “the trench,” the nickname for the first row of consoles.

Griffin served in the U.S. Air Force but had set his eyes on NASA when he saw Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin become the first man in space on April 12, 1961. Flight dynamics officer Dave Reed built model airplanes growing up, but switched to rockets when he was 15 after watching the Soviet Union become the first country to successfully launch a satellite on Oct. 4, 1957. And watching the Saturn V rocket launch the Apollo astronauts into space was like coming full circle for flight controller Charles “Chuck” Deiterich, the son of an airport mechanic who drew pictures of rockets in junior high school; he ended up computing the throttle-down time for the lunar module’s descent to the moon’s surface and the maneuvers for the astronauts’ return to Earth.

“I’m like an orchestra conductor,” Christopher Columbus Kraft, Jr., flight operations director for the Apollo missions told TIME back then. “I don’t write the music, I just make sure it comes out right.” The “windowless” Mission Operations Control Room was his “unlikely podium” on the third floor of Building 30 at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center, TIME reported. The flight controllers wee “his musicians,” sitting in “four rows of gray computer consoles, monitoring some 1,500 constantly changing items of information registered on gauges, dials and meters.”

The Mission Control staffers had gotten to know the astronauts well too, working closely with them during simulations and in mission-planning meetings. In fact, Armstrong went to visit Bostick when he got back from the post-moon world tour. (Armstrong arrived when Bostick was napping, and the flight controller’s son closed the door on the astronaut, who later told Bostick that he got a good laugh out of it.) But as these work relationships became tighter, some staffers grew farther apart from the other people in their lives. Aaron jokes that he and his wife technically had two kids at the time, “but she raised three,” because he had so little time to do anything for himself. Apollo meant many nights eating dinner at work and sleeping in the Mission Control Center’s sleeping quarters. Reed’s marriage ended after the moon landing, and so did Bostick’s.

Overall view of the Mission Operations Control Room in the Mission Control Center, Building 30, Manned Spacecraft Center, showing the flight controllers celebrating the successful conclusion of the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission.

The flood of nostalgia and commemoration that has accompanied the 50th anniversary of the landing has prompted those who saw it up-close to reflect on how it happened — and what’s changed since then. Many of the men who were behind the scenes are now front in center in interviews and archival footage re-released, such as the 2017 documentary Mission Control: The Unsung Heroes of Apollo, and the 2019 documentaries Apollo: Missions to the Moonand Apollo 11.

During the final Apollo mission, Apollo 17, in December 1972, Griffin remembers shooting the breeze with a bunch of guys huddled around his desk, disappointed about the program ending, and telling them to cheer up by saying that by the early 1990s they’d be on Mars, so not to worry about the lack of future missions to the moon. “So don’t ask me to predict the future of spaceflight,” he says, “because I was not accurate at all.”

The aptly named Bill Moon, who sat in a staff support room that assisted the Mission Operations Control Room, laments the irony of working so hard to beat the Russians and now relying on them to get American astronauts to space. “I’ll be glad when we start having our own ride and not having to depend on the Russians,” he says. “It’s a matter of pride.”

Three months after John F. Kennedy"s 1961 speech committing the country to "landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth," NASA awarded its first contract for the fledgling Apollo program.

It wasn"t for a spacecraft or launch facilities, but for a box - a computer that would guide the astronauts across the 250,000 miles to their objective. The Apollo guidance computer was designed at Charles Stark Draper"s Instrumentation Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It was built at Raytheon facilities in Sudbury and Waltham.

MetroWest companies and organizations played key roles in the Apollo program, from making sure spacecraft made it to the moon to feeding the astronauts and helping them communicate with Houston"s Mission Control.

"But nobody really knew what they were doing, because no one had ever done anything like it before," said David Mindell, an MIT professor and author of "Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Space Flight."

Early versions of the guidance computer were built at Raytheon"s Boston Post Road facility in Sudbury. Later, production moved to Seyon Street in Waltham, where all of the computers that flew in Apollo spacecraft were built.

"It"s mentioned to me frequently nowadays about how the (Apollo) computer doesn"t have as much memory or capability as a watch does nowadays," he said, "but we never thought of it that way. We thought of it as the best that was available at the time. And so we were glad to have these computers."

The Apollo guidance computer"s software was actually hardware. Every time a wire went through one of the magnetic cores, it represented a "1" in binary code - the building block of computer language - and if it was guided around the core it was a "0."

The core rope accounted for 74 kilobytes of read-only memory that was programmed before each Apollo flight. The computer also had 4 KB of rewritable memory used for temporary programs and data.

"When the programmers finally figured out what they wanted to do for the mission, they would release a deck of (computer punch) cards that went to the machine in Waltham," Poundstone said. The women "had to work very fast. They would have to get this thing built in time to get it shipped down to (Cape Canaveral) and installed, checked out and be ready for the launch. Every mission went through this same kind of a crisis to get these core ropes built in time."

Each memory module was tested extensively by Raytheon before being delivered to NASA. Mary Lou Rogers, of Waltham, worked on a different part of the Apollo production line, but in a recent BBC interview, she recalled the testing process.

The Apollo guidance computer proved itself to be reliable and accurate. It never failed in flight and, during Apollo 11, only two small mid-course corrections were required on the three-day coast to the moon.

"The computers were wonderful," Bean said. "They worked perfectly on all the missions. We, every once in a while, would put in a wrong number or read it wrong or do something like that, but it didn"t have any effect on any of the missions."

During the launch of Bean"s Apollo 12 mission, the Saturn V rocket that propelled the spacecraft to the moon was struck twice by lightning, disrupting power to the computer.

When the astronauts reached Earth orbit they realigned their guidance platform and were able to continue with the mission, all thanks to the computer"s core rope memory made by the little old ladies of Waltham.

On Apollo 13, when an oxygen tank exploded in the service module mid-flight, the command module had to be shut down. When the computer was restarted in preparation for re-entry, it had survived three days of extreme cold and condensation with no ill effect.

As the moon landings ended in 1972, the computers continued to be used in the three Apollo spacecraft that visited the Skylab space station and one that took part in the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project.

Bob Zagrodnick, a former Apollo program manager who works at Raytheon in Sudbury, said the Apollo guidance computer changed the way people thought about computers.

"The technology was so new 40 years ago," he said, "it was at the forefront of everything. Graduate computer architecture classes were just beginning to be offered at universities. But the success of the Apollo 11 mission and of the AGC sparked a new movement in computer architecture."

After Apollo, Raytheon went back to making Navy missiles, building guidance computers for the Poseidon and Trident. Said Poundstone, "basically, it was the same team of people who had worked the Navy programs that also worked the Apollo program."

"(Apollo) was probably one of the best programs the government"s ever had," he said. "The people involved had an awful lot of enthusiasm and dedication. Everybody, all the contractors, government people, MIT Instrumentation Lab people all worked very, very hard and long, long hours to make (the moon landings) a success."

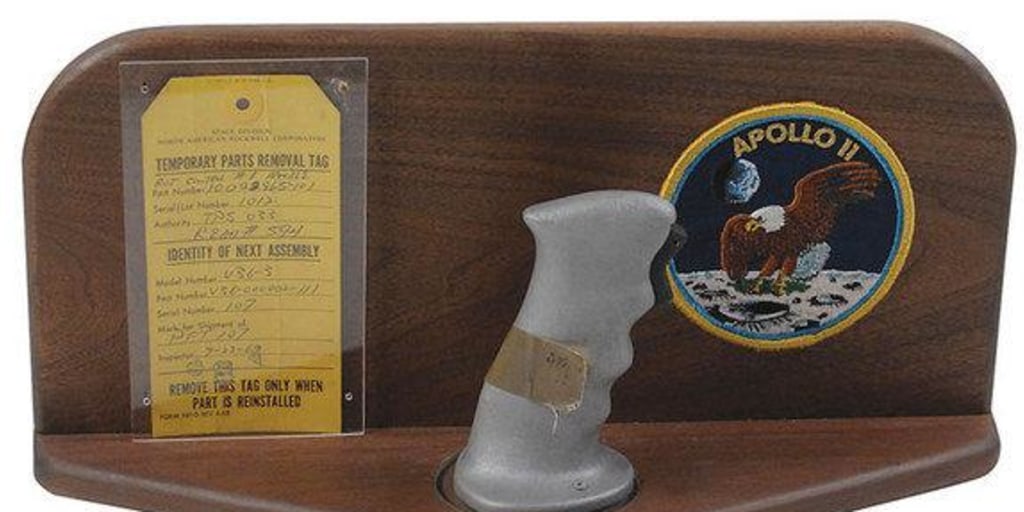

If it weren’t for a small felt-tipped pen and the quick thinking of the astronauts, the outcome of the Apollo 11 mission could have ended in disaster.

Designed by Duro Marker, the pen used to fix the broken switch and bring the Apollo 11 astronauts back to Earth is on display at The Museum of Flight in Seattle, Washington, accompanied by the original broken circuit breaker switch.

All three astronauts had previously completed NASA space missions as part of the Gemini space programme. None of them went into space again following Apollo 11.

After landing back on Earth, the Apollo 11 crew had to go through customs - as though they were returning from another country rather than from space. The items they declared included Moon dust and Moon rocks.

Neil Armstrong couldn’t afford to take out life insurance in case anything went wrong on the mission. As an alternative, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins signed hundreds of photographs so that Armstrong’s family could sell them in a worst case scenario.

The Apollo 11 mission launched on July 16 1969 13:32. The rocket was Saturn V which had launched 13 times from the Kennedy Space Center over six years.

8613371530291

8613371530291