apollo 11 mission parts in stock

Apollo 11 is a 2019 American documentary film edited, produced and directed by Todd Douglas Miller.Apollo 11 mission, the first spaceflight from which men walked on the Moon. The film consists solely of archival footage, including 70 mm film previously unreleased to the public, and does not feature narration, interviews or modern recreations.Saturn V rocket, Apollo crew consisting of Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong, and Michael Collins, and Apollo program Earth-based mission operations engineers are prominently featured in the film.

The film premiered at the Sundance Film Festival on January 24, 2019, and was released theatrically in the United States by Neon on March 1, 2019. Apollo 11 received acclaim from critics and grossed $15 million. The film won a leading five awards at the 4th Critics" Choice Documentary Awards, including Best Documentary Feature. It also received five nominations at the 72nd Primetime Creative Arts Emmy Awards, including Outstanding Cinematography for a Nonfiction Program for Aldrin and Collins, winning three for its editing and sound.

In late 2016, Todd Douglas Miller had recently completed work on The Last Steps, a documentary about Apollo 17,50th anniversary of Apollo 11.CNN Films subsequently became a partner in the film.direct cinema approach. The final film contains no voice-over narration or interviews beyond what was available in the contemporary source material. Portions of the mission are illustrated by animated graphics depicting the parts of the Apollo spacecraft as line drawings, the designs of which are based on the cel-animated graphics in Theo Kamecke"s 1971 documentary Edwin Aldrin, Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins up to 1969 by means of family photographs and archive footage.

In May 2017, cooperation between Miller"s production team, NASA, and the National Archives and Records Administration resulted in the discovery of unreleased 70 mm footage from the preparation, launch, mission control operations, recovery and post flight activities of Apollo 11.Launch Complex 39, spectators present for the launch, the launch of the Saturn V rocket, the recovery of astronauts Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong, and Michael Collins and the Apollo 11 command module USS Hornet. The documentary included this footage alongside conventional footage from 35 and 16 mm film, still photography, and closed-circuit television footage.

Miller"s team used the facilities of Final Frame, a post-production firm in New York City, to make high-resolution digital scans of all reels depicting ground based activities that were available in the National Archives. Specialized climate-controlled vans were used to safely transport the archival material to and from College Park, Maryland. The production team sourced over 11,000 hours of audio recordings and hundreds of hours of video.Mother Country", a song by folk musician John Stewart, in Lunar Module voice recordings. The song was subsequently featured in the film.

A 47-minute edit for exhibition in museum IMAX theaters Apollo 11: First Steps Edition includes extended large-format scenes that differ from the full-length documentary.

A soundtrack album Apollo 11 (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) composed by Matt Morton was released worldwide by Milan Records on digital download on March 8, 2019. Played entirely on electronic instruments actually available in 1969, the seventeen-track album was also released on CD on June 28 and vinyl on July 19, 2019.

The film took some liberties with the timeline of the mission. For example, an incident occurred during the return voyage, on day 8 of the mission, involving the disconnection of Michael Collins"s biomedical sensor (his impedance pneumograph), which led him to wisecrack, "I promise to let you know if I stop breathing,"command module Columbia and Lunar Module Eagle.

The world premiere of Apollo 11 took place in Salt Lake City at the Sundance Film Festival on January 24, 2019.limited release in the United States on March 1, 2019 in IMAX through Neon and was released in the United Kingdom on June 28, 2019 through Universal Pictures and Dogwoof.

Universal Pictures released Apollo 11 in the U.S. on digital download, DVD and Blu-ray on May 14, 2019. The discs have two extra features; a 3-minute featurette titled Apollo 11: Discovering the 65mm and a theatrical trailer.4K Ultra HD two-disc set in the United Kingdom on November 4, 2019 by Dogwoof.

Upon its premiere at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, the film was acclaimed by critics, who mostly praised the quality of the film"s footage. On Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 99% based on 186 reviews, with an average rating of 8.9/10. The website"s critical consensus reads, "Edifying and inspiring in equal measure, Apollo 11 uses artfully repurposed archival footage to send audiences soaring back to a pivotal time in American history."Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 88 out of 100, based on 34 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".

In a positive review for Moon landing sequence feel unique and thrilling, and stated that the clarity of the footage "takes your breath away".Damien Chazelle"s 2018 Neil Armstrong biopic Matt Zoller Seitz of RogerEbert.com gave the film four-out-of-four stars, calling the film "an adrenaline shot of wonder and skill.... Films this completely imagined and ecstatically realized are so rare that when one comes along, it makes most other movies, even the good ones, seem underachieving. Any information that you happen to absorb while viewing Apollo 11 is secondary to the visceral experience of looking at it and listening to it."

Independent researcher James Meador at the California Institute of Technology had an idea: using new gravitational data of the Moon, maybe he could track where the Apollo 11 ascent stage crashed after it returned astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the command module following the first lunar landing in 1969. He was thrilled to pursue the chance to locate the impact site on the moon for history’s sake.

In doing his research, Meador used data from the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory mission by NASA, which used two spacecraft to detect gravitational fluctuations of the moon. When he entered those numbers into the General Mission Analysis Tool simulator, an open-source space navigation calculator, he expected to find the place where the Eagle had crashed into the moon. Instead, the trajectories were showing the vehicle was still in orbit at roughly the same distance from the surface as when it was released five decades ago, reports David Szondy of New Atlas.

The exact fate of the Eagle is still unknown, mainly because NASA does not track its spacecraft after a mission is over. It could still be in lunar orbit, according to Meador’s calculations, or it could have exploded. The United States space agency speculates that leaking fuel and corrosive batteries may have caused the module to succumb to aging hardware instead of gravity, reports Discovermagazine.

What would it be like if we could recreate a single day in our past? Not just the parts we remember, the events to which we attribute great significance, but the whole day filled with all its interacting parts. This is the premise behind one of the new exhibits under development for the National Archives Experience, "20 July 1969." Millions of Americans—and millions of others around the globe—remember the summer of 1969 as the time humans first landed on the Moon. Culminating with Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong"s first step onto the Moon on July 20, 1969, the space flight, the lunar landing, and the crew"s safe return to earth were seen as epochal events, worthy of intense media coverage, international celebration, and careful social analysis. The events surrounding the Moon mission were recorded and noted in great detail. Nowhere was this truer than in the many agencies that make up the federal government of the United States. "20 July 1969" will show how this momentous episode in American history affected the work of the entire government and how the world reacted to Armstrong"s "giant leap for all mankind." Using original documents, photographs, and video clips set in an environment reminiscent of a NASA "mission control" station, the exhibit will recreate this one historic day in the nation"s history.

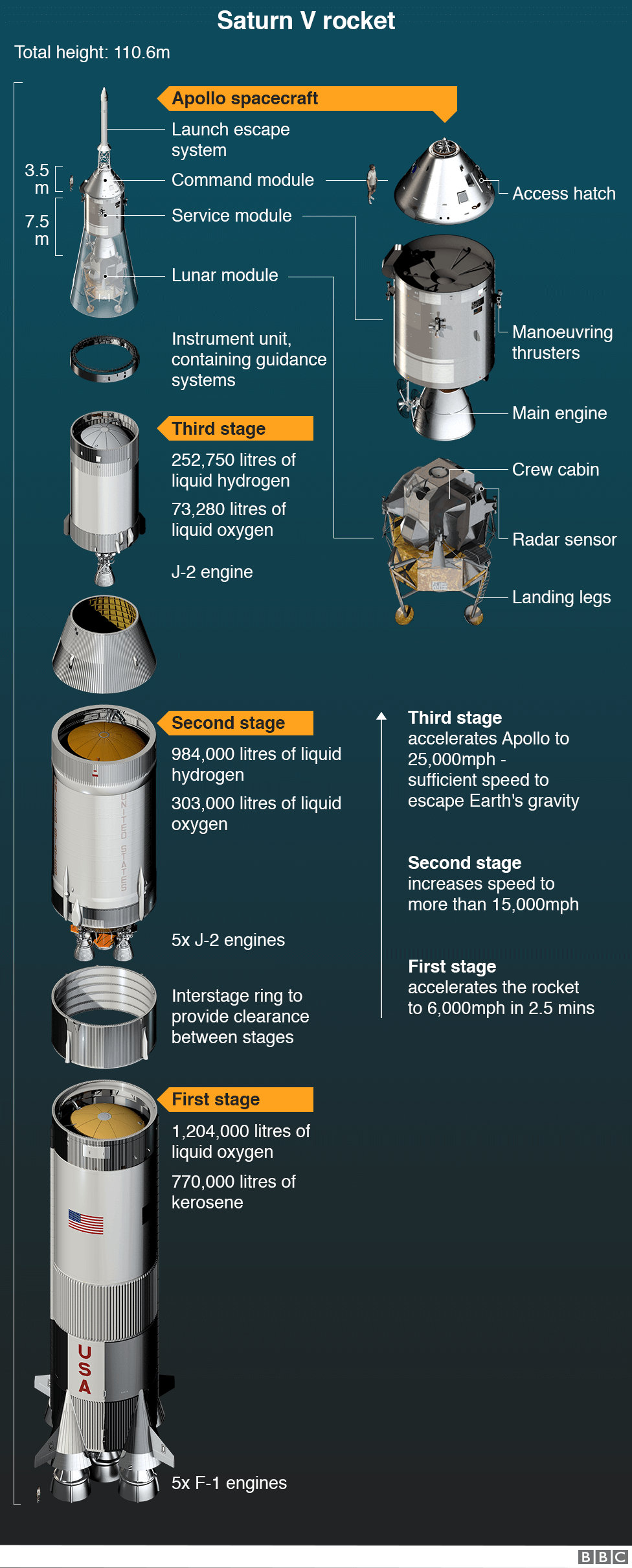

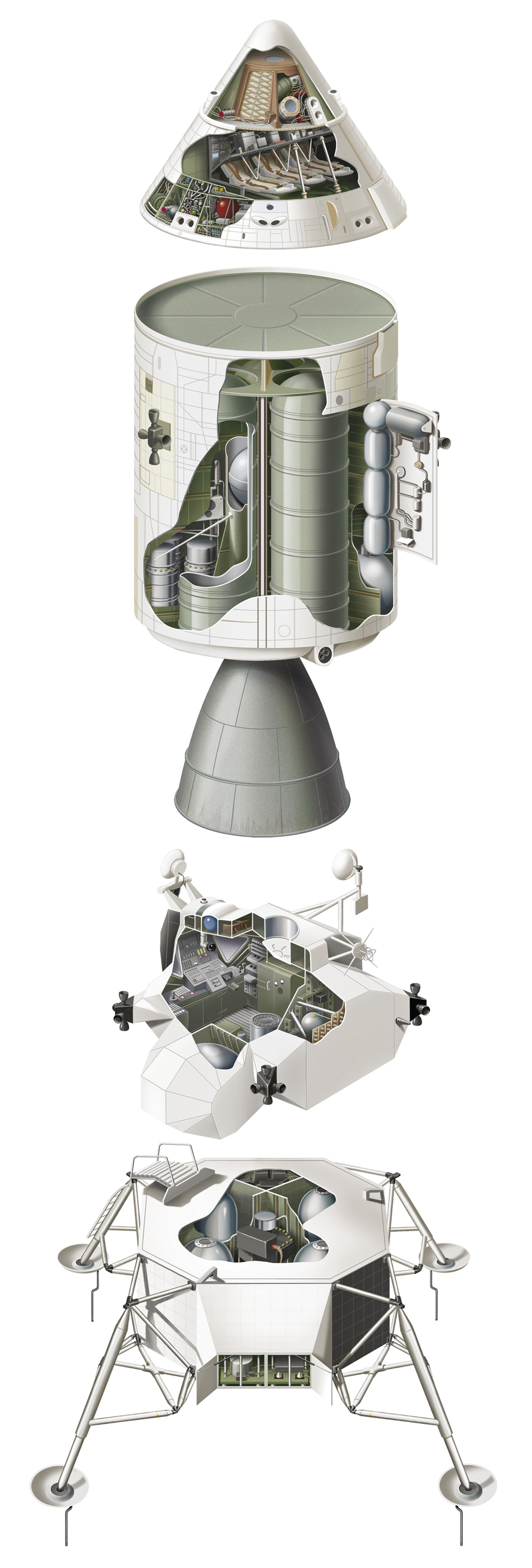

On the morning of July 16, 1969, an enormous three-stage Saturn V rocket—the largest rocket ever built—stood on launch pad 39A at Cape Kennedy, Florida. The Saturn V stood 281 feet high and weighed 6.2 million pounds. Its first-stage liquid fuel engines produced 7.5 millions pounds of thrust—enough power to light up all of New York City for an hour and a half. On top of the Saturn V, three Apollo 11 astronauts—Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin— waited in their tiny "Command Module," over three hundred feet above the ground. Attached below them were a "Service Module," whose engine would be used to take them out of Earth orbit, and a "Lunar Module," named Eagle, which would be used to take Armstrong and Aldrin to the surface of the Moon and back to Collins, who would orbit the Moon in the Command Module, for the trip home. At just after 9:30 A.M., the long countdown ended, and the Saturn rocket"s engines ignited. The huge rocket rose off the ground. In minutes, the crew was in Earth orbit. Shortly afterward, the single booster in the Service Module launched them out of orbit and toward the Moon. For the next eight days, the world watched as Apollo 11 flew to the Moon, Armstrong and Aldrin landed and explored its surface, linked up with Collins, and returned to Earth. While they were away, much of the federal government focused on their voyage.

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which ran the mission, was of course fully devoted to Apollo 11. But other agencies integrated the Moon landings into their work as well. The White House planned for "Presidential Activities" related to the mission. The State Department accepted the best wishes and congratulations of foreign governments. The United States Information Agency, which was responsible for keeping foreign populations informed of the progress of the flight, sponsored public television viewings of mission events for citizens of other countries at American cultural centers. The U.S. Navy rehearsed its role in the successful recovery of the spacecraft at sea. Congress considered how to honor the nation"s newest heroes.

Documents from the National Archives record the history of Apollo 11 and the world"s reaction to it. A NASA "Data Card Kit," for example, provides a record of the astronauts" activities on the lunar surface. These cards detailed the procedures followed during Armstrong and Aldrin"s "extra vehicular activity" (EVA) on the Moon such as photography, inspecting equipment, and collecting samples of lunar soil. A similar checklist describes the countdown for the crucial "TLI" (Translunar Injection), which would fire the rocket on the third stage of the Saturn and accelerate the astronauts out of Earth orbit. The backside of a photography checklist, labeled "Ye Ole Lunar Scratch Pad," strikes a more whimsical note. These pads gave the astronauts space to write notes with grease pencils that had been sewn onto their uniforms. All the checklists have small squares of Velcro that could be attached to other Velcro squares on space suits or in the crew compartments.

Among military records in the National Archives, the log book for the aircraft carrier USS Hornet chronicles the ship"s preparation for Apollo 11"s Pacific Ocean landing and its role in recovering the astronauts and their spacecraft. On July 20 the Hornet"s officer of the deck, Lt. (jg) J. S. Lauck, noted only briefly that the "Apollo Eleven Lunar Module has landed safely on the Moon." Four days later, Lt. W. M. Wasson"s more detailed entry describes the launch of aircraft used in the recovery operations, the landing of "R. M. Nixon, President of the United States," the "splash-down" of the Command Module, and the safe recovery of "N. A. Armstrong, LCOL M. Collins, USAF, and Col. E. E. Aldrin, Jr., USAF."

Thousands of miles away, near Hue, South Vietnam—where July 20 was already July 21—the men of another military unit, the Second Brigade of the U.S. Army"s 101st Airborne Division, were equally busy. The brigade"s Daily Staff Journal describes spotting North Vietnamese soldiers, destroying unexploded rockets, and blowing up enemy bunkers. Nevertheless, despite the pressures of war, Capt. David T. Gibson still found time to note in the diary, "At 1103 hrs the first man walked on the moon."

When Armstrong took those first few steps away from Eagle, nearly 600 million people watched. The Moon landing was the most watched event in television history; such an unprecedented audience provided unprecedented media opportunities. At the Nixon White House, presidential advisers had been planning for weeks how the chief executive and first lady would respond to Apollo 11. The President would call the astronauts the day before their liftoff, while the first lady would call the astronauts" wives. After a successful Translunar Injection, Nixon would proclaim July 20 a holiday—Moon Day—"allowing all Americans to watch the Astronauts" activity." Once Armstrong and Aldrin were safely on the surface, the President would make the world"s first "interplanetary" congratulatory telephone call from the Oval Office, during which he would express his pride in the American space program"s achievement. He would also state his belief that the Moon landing had given the world "one priceless moment, in the whole history of man [in which] all the people on this earth are truly one."

Documents from the Nixon presidential materials in the National Archives capture the painstaking preparation and planning for these events. A commemorative "first-day issue" stamp, made from a die carried to and from the Moon by Apollo 11 and held among the Nixon presidential materials, preserves the words of that telephone conversation.

WRIGHT-PATTERSON AIR FORCE BASE, Ohio – The United States recently celebrated the 50th anniversary of Neil Armstrong’s historic walk on the moon. Project Apollo, led by NASA in the 1960s and 70s, achieved this feat following years of research, development and precursor missions. While countless individuals and organizations enabled the space program, the Air Force Research Laboratory played a supporting role by making the historic moon landing possible through the marvels of science and engineering.

Kevin Rusnak, AFRL senior historian, explains that, “Apollo built on the tremendous technological organizational base that had been set through the Gemini program, the Mercury program and then going back to the Air Force and other parts of the military.” He asserts that the military’s contributions were instrumental to the success of the U.S. Space Program.

In a recent Lab Life Podcast, Rusnak explains how AFRL technology supported the famed Apollo 11 mission in 1969. As far back as 1920, McCook Field scientists developed systems and pioneered equipment that eventually supported U.S. astronauts.

From the pressurized spacesuits and helmets to the rocket engine that powered the launch and the algorithm that guided the lunar module to the moon"s surface, Air Force inventions accompanied astronauts on their journey to space. AFRL and its predecessors also supported NASA missions by developing fuel cell technology, specialized composites and high-speed/heavy-load parachutes. Rusnak says that these contributions ultimately helped the U.S. achieve its goal of putting a man on the moon.

In the 1940s, scientists from the Aero Medical Laboratory at Wright Field (now the 711th Human Performance Wing) developed pressure suits that enabled pilots to survive at high altitudes. When NASA formed in 1958, it relied on the Air Force’s expertise to evaluate its first generation of space suits based on mobility, comfort and inflation.

While the Apollo program required an entirely new type of suit, Rusnak explains that NASA continued to rely on the principles and techniques established by the Aero Medical Laboratory, as well as its experts and industrial partners. Ultimately, NASA incorporated several Air Force principles, including material choice, into the design for the Apollo multi-layered lunar spacesuit.

According to the National Air and Space Museum, the Apollo pressure helmet featured a transparent bubble made from polycarbonate. The helmet attached to the spacesuit via an aluminum neck ring. Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin wore visor assemblies, also made of polycarbonate, over their pressure helmets when they were outside of the spacecraft.

The F-1 engine, the first stage of the Saturn V rocket, lifted the astronauts off the ground during the Apollo 11 launch and placed a 50-ton spacecraft in a lunar trajectory. Rusnak explains that the Saturn V incorporates five massive F-1 engines, which equates to 7.5 million pounds of thrust.

Along with the astronaut equipment and rocket engines, AFRL supported the descent stage of the moon landing. According to AFRL’s History Office, an algorithm known as the Kalman filter guided the Apollo 11 lunar module to the moon"s surface.

Rusnak explains that, “long-duration space flights required electrical production over a period of two weeks and in the several kilowatt range, clearly outside the realm of battery power.” First, “Gemini proved the technology was viable, and then every Apollo lunar mission used fuel cells derived from the technology developed by AFRL’s predecessors.”

AFRL also worked on products that helped the Apollo 11 astronauts return safely to Earth. In 1963, the Air Force Materials Lab (now the Materials & Manufacturing Directorate) scaled up silicon carbide coated carbon-carbon composites, later used on the command module’s nose cone.

Finally, to land safely, the Apollo 11 crew used a multi-parachute system to slow their rate of descent and reduce the force of impact. McCook Field engineers had perfected the design of free-fall parachutes in the 1920s, while their successors at Wright Field developed high-speed, high-strength parachute systems that fit tightly into small packages. These technologies transferred directly to the Apollo landing system

Ultimately, the Apollo 11 crew successfully traveled to space, walked on the moon and returned to Earth, thanks in part to technologies developed by AFRL and its predecessors.

Sean Solomon has served as the director of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory since 2012. Much of his recent research has focused on the geology and geophysics of the solar system’s inner planets. He was the principal investigator for NASA’s MESSENGER mission, which sent the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury and study the planet’s composition, geology, topography, gravity and magnetic fields, exosphere, magnetosphere, and heliospheric environment.

The beginning of Solomon’s research career coincided with the birth of a new field — planetary science. Below, he explains how Apollo 11 affected the scientific community at that time, how Lamont was involved, and what comes next for lunar exploration.

Solomon discussed these topics and more during a panel discussion entitled “Small Steps and Giant Leaps: How Apollo 11 Shaped Our Understanding of Earth and Beyond” on July 17. The event, hosted in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing, was co-sponsored by the American Geophysical Union and the National Archives.

I was a graduate student at MIT, and I was doing a thesis in seismology. However, I had written a paper about the interior structure of the Moon before the Apollo 11 mission. MIT faculty and students were holding discussions about the Moon in advance of the Apollo 11 landing, so we were primed to think about the impact of the mission’s findings.

In terms of my own work, the mission led to an explosion of new data about the Moon. I included lunar work in my research agenda for a number of years thereafter, using data from all of the Apollo missions, from the findings of sample analyses to the observations from the orbital and surface experiments that Apollo carried.

There was really no field of planetary science in 1969, just a handful of people who called themselves planetary astronomers and studied other worlds through telescopes or with theoretical work. NASA had sent spacecraft to Venus and Mars by the time of Apollo 11, so there were a few people who were working on planetary data, but the space age was less than 12 years old at the time of the first Moon landing. Almost everybody who worked on the scientific return from the Apollo program came from other fields — earth science, chemistry, or physics — and they became lunar scientists. NASA’s investments brought in huge numbers of scientific experts and funded new instruments and labs across the county to create a lunar community that hadn’t been there before.

It’s also important to remember that nearly coincident with the Apollo program was an explosion of robotic missions to explore other parts of the solar system. Within a few years of Apollo 11 we had launched spacecraft to fly by Mars, Venus, Mercury, Jupiter, and Saturn. It was an enormous expansion of our presence in space that was enabled by a healthy NASA built up to conduct the Apollo missions but an agency that also had the budget and the engineering expertise to figure out how to explore the rest of the solar system by spacecraft. The field of planetary science came into its own in those few years after Apollo.

Several Apollo missions carried a seismic experiment led by Lamont’s Gary Latham (left), shown here monitoring the signal from his experiment. Photo: NASA

Lamont was very heavily involved in the Apollo program and was much more active in planetary research than it is now. There were Lamont scientists who were in line to receive some of the first samples brought back from the Moon. At least equally importantly, Lamont was a leader in the geophysical exploration of the Moon. Over the course of the Apollo missions there were several geophysical experiments, but the one that spanned nearly all of the missions was the passive seismic experiment. And several early Lamont seismologists had teamed together to put that experiment on Apollo, including Maurice Ewing, Frank Press, Gary Latham — the principal investigator — and other team members from Lamont as well.

In later Apollo missions, astronauts measured the heat flowing out from the lunar interior. The Apollo Heat Flow Experiment was led by Marcus Langseth, a Lamont scientist for whom our current research ship is named. Also, during the Apollo 17 mission, there was a gravimeter that was mounted on the astronauts’ rover to measure the variation in lunar gravity over the course of the rover traverse. That experiment was led by Manik Talwani, who by then was the Lamont director.

Apollo also provided our first detailed look at another planetary body. And it showed us how special the Earth-Moon system is. It was the Apollo 11 mission that demonstrated convincingly for the first time how ancient the Moon is — the samples brought back were more than 3 billion years old. We learned that the Moon recorded and illuminated a period of solar system history that we hadn’t begun to appreciate through our study of Earth. There’s no rock record on Earth for the first half billion years, but there is on the Moon. And because the Moon is our satellite, it’s part of our history, too. We learned how violent and chaotic the earliest history of the solar system was. We wouldn’t have gained that perspective without leaving Earth.

As a nation, we put a big priority on meeting the goal that Kennedy set out. And throughout most of the 1960s we had Democratic presidents, Kennedy and Johnson, who were supportive of that program. In the 60s, the funding was there, and America’s reputation was at stake. There were military implications to the control of space. We were in the middle of the Cold War. There were many reasons we put the resources behind the Apollo program. NASA was a pretty daring agency at that time. They were willing to take risks. They didn’t want to risk more human lives than they needed to, but the astronauts were putting their lives on the line. The first astronauts were test pilots, who risked their lives every day over the course of their work; they knew what the risks were. NASA was a different agency back in the 60s than it has been since. Their engineers and managers set their sights high and did what they needed to do to meet schedules. And they had the resources to do it.

When the Apollo program was underway we were sending two missions a year to different parts of the Moon. There was to have been an Apollo 18, an Apollo 19, and an Apollo 20, but these were expensive missions, and in 1972 the U.S. was spending a lot of money fighting the war in Vietnam. Those missions were cancelled, even though all of the hardware had been built and the astronauts that would fly those missions had been selected, and that decision ended the Apollo program. It was a challenge to devise experiments that could build on Apollo’s legacy and yet be done inexpensively with robotic spacecraft, which were being sent to many other targets — Mars, Venus, Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, and, a few years later, Uranus and Neptune.

NASA did not return again to the Moon until the 1990s, with the Clementine orbiter — sponsored jointly with the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization — and the Lunar Prospector orbiter. Ten years ago, NASA launched the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which is still operating at the Moon, and other missions have followed. Space organizations in other countries have also launched lunar missions, including the Soviet Union prior to and even after the Apollo missions, and later Japan, India, China, and Israel. In the U.S. and abroad, there are commercial entities that have their sights set on lunar landing. And earlier this year NASA announced plans to send the first woman and the next man to the Moon by 2024. If that goal is to be met, partnership with the commercial sector will be needed.

I hope for two takeaway messages. First, the Apollo 11 mission was not only a remarkable technological achievement in the history of our species, but it also marked a “giant leap” in our appreciation of Earth’s place in our planetary system. And second, the Moon today still holds answers to important questions about the early history of our planet, and there remain myriad scientific as well as political and commercial reasons to return.

8613371530291

8613371530291