overshot bite in dogs factory

An overbite might not seem like a serious condition for your dog, but severely misaligned teeth can lead to difficulty eating, gum injuries and bruising, bad breath and different types of dental problems, including tooth decay and gingivitis. Fortunately, there are ways to help fix the problem before it becomes irreversible.

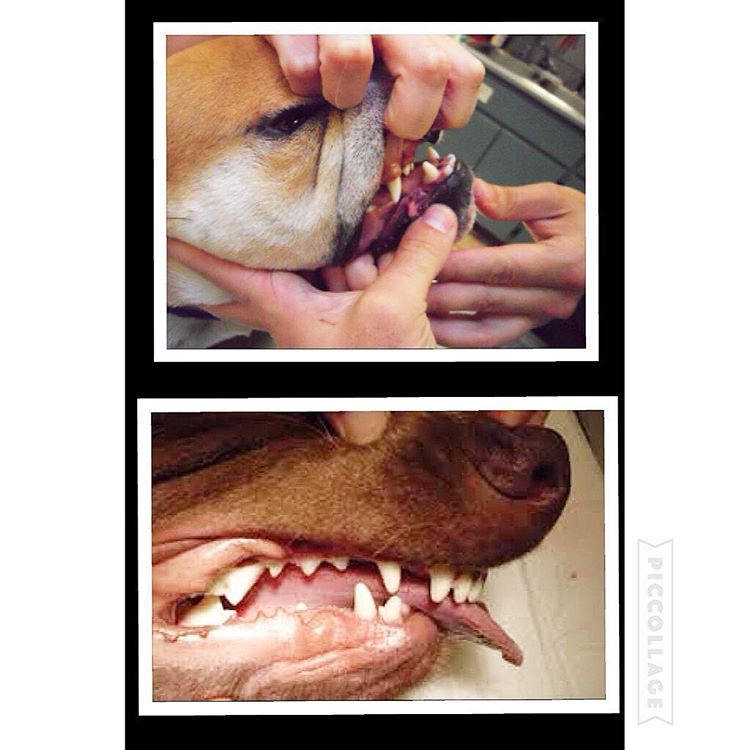

An overbite is a genetic, hereditary condition where a dog"s lower jaw is significantly shorter than its upper jaw. This can also be called an overshot jaw, overjet, parrot mouth, class 2 malocclusion or mandibular brachynathism, but the result is the same – the dog"s teeth aren"t aligning properly. In time, the teeth can become improperly locked together as the dog bites, creating even more severe crookedness as the jaw cannot grow appropriately.

This problem is especially common in breeds with narrow, pointed muzzles, such as collies, shelties, dachshunds, German shepherds, Russian wolfhounds and any crossbred dogs that include these ancestries.

Dental examinations for puppies are the first step toward minimizing the discomfort and effects of an overbite. Puppies can begin to show signs of an overbite as early as 8-12 weeks old, and by the time a puppy is 10 months old, its jaw alignment will be permanently set and any overbite treatment will be much more challenging. This is a relatively narrow window to detect and correct overbites, but it is not impossible.

Small overbites often correct themselves as the puppy matures, and brushing the dog"s teeth regularly to prevent buildup can help keep the overbite from becoming more severe. If the dog is showing signs of an overbite, it is best to avoid any tug-of-war games that can put additional strain and stress on the jaw and could exacerbate the deformation.

If an overbite is more severe, dental intervention may be necessary to correct the misalignment. While this is not necessary for cosmetic reasons – a small overbite may look unsightly, but does not affect the dog and invasive corrective procedures would be more stressful than beneficial – in severe cases, a veterinarian may recommend intervention. There are spacers, braces and other orthodontic accessories that can be applied to a dog"s teeth to help correct an overbite. Because dogs" mouths grow more quickly than humans, these accessories may only be needed for a few weeks or months, though in extreme cases they may be necessary for up to two years.

If the dog is young enough, however, tooth extraction is generally preferred to correct an overbite. Puppies have baby teeth, and if those teeth are misaligned, removing them can loosen the jaw and provide space for it to grow properly and realign itself before the adult teeth come in. Proper extraction will not harm those adult teeth, but the puppy"s mouth will be tender after the procedure and because they will have fewer teeth for several weeks or months until their adult teeth have emerged, some dietary changes and softer foods may be necessary.

An overbite might be disconcerting for both you and your dog, but with proper care and treatment, it can be minimized or completely corrected and your dog"s dental health will be preserved.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Occlusion is defined as the relationship between the teeth of the maxilla (upper jaw) and mandibles (lower jaw). When this relationship is abnormal a malocclusion results and is also called an abnormal bite or an overbite in dogs and cats.

The mouth is split into quadrants: left maxilla, right maxilla, left mandible and right mandible. Each quadrant of the mouth in both dogs and cats contains incisors (I), canines (C), premolars (PM) and molars (M).

In the normal, aligned mouth, the left and right side mirror each other. Dogs have a total of 42 adult teeth and cats have 30 adult teeth. The normal occlusion of a dog and cat mouth are similar. Below we"ll share how malocclusions can affect both canines and felines.

A malocclusion in that case, is either a tooth in an abnormal position and/or the misalignment of the maxilla and mandible with respect to one another."

A Class I malocclusion takes place when one or more teeth are in an abnormal position, but the maxilla and mandibles are in a normal relationship with each other. A Class I tooth may be pointing in the wrong direction or rotated.

Class III malocclusions are considered underbites in dogs and cats; the mandibles are longer in respect to their normal relationship to the maxilla. Class III malocclusions are commonly seen in brachycephalic dogs (boxers, pugs, boston terriers, etc).

Class IV malocclusions result from asymmetrical development of the maxilla or mandibles. The asymmetry of this malocclusion results in skeletal malformations leading to a side to side malalignment.

While cats do not get malocclusions nearly as frequently as dogs, they are not free from this problem. When present, felines malocclusions tend to be more severe and can cause more problems. There is a definitely a breed predisposition for cats with malocclusions. Persians and Himalayan cats tend to have a higher incidence of malocclusions, most frequently underbites.

Just as with dogs, cats with malocclusions should always be evaluated by a veterinarian and treated if their bite is traumatic and causing them pain. Malocclusions are frequently diagnosed in kittens. These abnormal bites are often painful and the sooner they are treated, the better the prognosis for gaining a pain-free and functional bite.

Malocclusions can result in an abnormal bite which can affect function and result in pain. Malocclusions predispose the patient to periodontal disease, endodontic (pulp) disease and oral trauma.

Our belief at Animal Dental Care and Oral Surgery is that all pets deserve a pain-free and functional bite. In most situations, the earlier a malocclusion is diagnosed the better the prognosis.

Class II and class III malocclusions are skeletal abnormalities resulting from abnormal development of the maxilla and mandible. It is rarely possible to restore the maxilla and mandibles to a normal relationship with each other, but it is always possible to permanently relieve pain that these malocclusions cause.

Although complete correction of certain teeth misalignments may not be possible, there is always something we can do to improve the functionality of the bite and make the patient comfortable. For best results, it is important to recognize a malocclusion as early as possible.

The upper incisor teeth slightly overlap the lower incisors. The lower canine tooth (fang) sits between the upper canine tooth and 3rd incisor. The premolar teeth do not touch each other and form zigzag-like pattern between the upper and lower premolars. The large upper 4th premolar tooth rests on the cheek side of the lower first molar. This tooth is also known as the upper carnassial tooth. The molars are not visible in this image.

Known as a canine overbite, the upper canine tooth is sitting in front of the lower canine tooth and is pointed forward. This is referred to as a mesioverted or “lance” canine tooth. Compare this image to the normal occlusion in figure 2.

Known as a canine underbite, the lower incisors are in front of the upper incisors and the lower canine tooth is resting against the back of the upper 3rd incisor. This bite is common in brachycephalic breeds, such as boxers and pugs.

Each side of the mandible developed at different rates resulting in a deviation to the left side. Note how the right lower canine is poking into the palate (roof) of the mouth. This is a significant source of pain for this patient.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Orthodontics and bite defects are a common reason for referral. The most common condition we see is lingual displacement of the lower canine teeth with consequent hard palate trauma with an inability to close the mouth. We have a separate page devoted this problem. Use this link - Lingually Displaced Lower Canines.

The dog above was referred because of the abnormal position of the lower incisors. Differential diagnoses included trauma with a blunt object or high speed collision with another dog. How wrong we were!

Our radiographs showed no actual trauma but complete avulsion of the teeth out of the sockets. The reason was the use of a powerful elastic band placed to straighten the teeth. The elastic band had slipped down the teeth and below the gum line. Once down there it pulled all five teeth out of their sockets and caused local bone damage by cutting off blood circulation. Apart from removal of the teeth extensive bone recontouring was required to remove dead bone and allow recovery.

Most cases are referred simply for a bite appraisal. Genetic counseling is an integral part of this consultation with written reports are provided for the owner and referring veterinary surgeon. These specialist reports often help clients in disputes with the breeder and, for breeders, in the future selection of stud animals. These are "expert reports" and can be used in legal disputes. An article written by us was published in Veterinary Times in December 2006. A PDF is available to download here.

A common condition in Shetland sheepdogs. Upper canines are in rostroversion and point forward like a lance. The teeth are often semi-erupted and located across the face with the root apex in the nasal cavity. Usually surgical extraction is the most reliable course of action. Any oral nasal fistula can be corrected at the time of surgery.

We do not perform orthodontics in these cases as the condition is most often due to a combination of long lower jaws (relative to the upper jaw) plus excessive crowding of the incisors. The correct term is mandibular mesioclusion or class 3 bite but undershot is the term in common use.

Since the origin is inherited, and does not cause pain or discomfort to the pet, long, involved and expensive treatment cannot be considered to be in the pets" best interest in our opinion.

There are several ethical concerns that have to be satisfied before undertaking any orthodontic treatment that may change the appearance of an animal with a bite defect. We are obliged to inform the Kennel Club of actions we take to alter the natural conformation of a dog. Potential clients are requested to download the form, complete it and bring it with you on the day. We also need your microchip number.

In the past we have had some clients who have refused to sign this form and have effectively wasted a long journey. It may be worth pre-warning potential referral clients before they travel.

It is very important for the welfare of the breed in general that an individual with a bite defect is not allowed to breed. To that end, major orthodontic work cannot be performed unless the animal has been neutered.

Many of these conditions are autosomal recessive mutations. This means that normal looking individuals can carry hidden recessive genes. If they mate with another recessive carrier there will be both normal and abnormal pups in the litter. Currently there are no tests available to identify a recessive carrier other than test mating.

This condition is most often spotted at either the first or second puppy checks or between 6 and 8 months of age as the permanent (adult) teeth erupt. Either the deciduous or permanent lower canines occlude into the soft tissues of the roof or the mouth causing severe discomfort and, possibly, oral nasal fistulae.

The fact sheet answers many questions you may have about the cause of this problem and the various treatments available. It is important not to delay treatment of deciduous lower canines as the window of opportunity is only a matter of a few weeks until the permanent canines erupt at 22 to 26 weeks of age. A new problem can then present with bigger teeth causing more damage.

We advise you email us images of the teeth (mouth closed, lips up and side on for both left and right) just a few days before you travel. Things change quickly in growing dogs and it might save you a wasted journey.

This is an inherited condition - an autosomal recessive mutation. Both parents may look normal but carry recessive genes for the condition. When this genetic information is passed onto the litter, approximately one pup in four will be affected, appear abnormal and can pass the genetic information on if bred from. In addtion, two pups in four will carry an abnormal gene from one parent and a normal gene from the other. This pups will look normal but can pass the problem on if bred. Finally one pup in four will not be a carrier of abnormal genes, will be unaffected and cannot pass the trait on to future generations.

If this condition appears in the litter, the most responsible course of action is not to breed from the parents again - either as a pair or individually with others. As there is currently no test to identify this gene, selecting another mate may mean they too are recessive carriers. All the normal looking sibling pups are likely to also carry the recessive genes. It is wise that they too do not contribute to passing the problem back into the breed"s gene pool. In many affected breeds, the gene pool of breeding individuals to select from is very small. If recessive carriers are routinely mating then it is not long before increasing numbers of pups appear with this condition. Over four decades we have monitored the breeds treated here and it is disappointing to note that many previously unaffected breeds are now being seen on a regular basis.

When a pup is treated for this condition we routinely supply the Kennel Club with a Change of Conformation form so they can track the parental origin. We also ask for permssion to send a DNA swab to the Animal Health Trust. This is anonymously evaluated as part of a research programme to identify the exact genetic origin of the condition with the aim of a simple test becoming available to identify recessive carriers. In time this will allow owners of known recessive carriers to select a mate unaffected by the condition.

Owners with young puppies identified with this problem at first presentation are advised to have the deciduous lower canines removed as soon as possible. There are three reasons for this:

Firstly, and most importantly, these teeth are sharp and hitting the soft tissues of the palate. These pups cannot close their mouth without pain and often hold the mouth slightly open to avoid contact. This is not pleasant. See above for an example of the damage caused to the hard palate by this problem.

Secondly, the growth of the mandible is rostral from the junction of the vertical and horizontal ramus. If the lower canines are embedded in pits in the hard palate, the normal rostral growth of the mandible(s) cannot take place normally due to the dental interlock caused by the lower canines being embedded in hard palate pits. This can cause deviation of the skull laterally or ventral bowing of the mandibles (lower jaws).

Thirdly, the permanent lower canine is located lingual to the deciduous canine. This means that if the deciduous lower canines are in a poor position it is a certainty the permanent teeth will be worse. See the radiograph below. The deciduous canines are on the outside of the jaws and the developing permanent canines are seen in the jaw as small "hats". It is clear that the eruption path of the permanent canines will be directly dorsal and not buccally inclined as is normal.

For these three reasons it is advisable to surgically remove the lower canine teeth as soon as possible to allow maximum time between the surgery and the time the permanent teeth erupt at between 22 and 24 weeks of age. See our file for illustration of removal of deciduous canines.

The deciduous tooth root is three to four times longer than the visible crown and curved - often 2.5cm in length and curved. The root apex is often located below the third lower premolar. See middle and right images below with extracted deciduous tooth laid over extraction site.

The roots are very fragile and will break easily if unduly stressed during removal. A broken root needs to be identified and removed otherwise it continues to form a barrier to the eruption path of the permanent canine and can cause local infection.

The permanent successor tooth is located lingual to the deciduous tooth and wholly within the jaw at this stage. Any use of luxators or elevators on the lingual half of the deciduous tooth will cause permanent damage to the developing enamel of the permanent tooth. See the images below showing canines (and also the third incisor) with extensive damage to the enamel. The radiograph also shows how much damage can occur to the teeth - see the top canine and adjacent incisor. Some severely damaged teeth need to be extracted while other can be repaired with a bonded composite. This damage is avoidable with careful technique using an open surgical approach.

Surgery to remove the deciduous canines may not prevent to need for surgery on the permanent canines but, without it, few cases will resolve if left to nature. Many owners are reluctant to have young pups undergo surgery. Our view is that surgical removal of the lower deciduous canines will not guarantee the problem does not happen again when the permanent teeth erupt but without surgery the chances are very slim.

In a few selected cases - usually only very mild lingual displacement - we can consider placing crown extensions on the lower canines to help guide them into a more natural position. It carries some uncertainly and will not be suited or work in all cases. The images below show crown extensions on a young Springer Spaniel.

Please note that the use of a rubber ball to assist tipping of the deciduous lower canines buccally is not appropriate at this age and will not work - see below.

If the permanent teeth are lingually displaced the pup is usually older than 24 weeks. The trauma caused by the teeth on the soft tissues can be considerable with pain as a consequence.

Do not try ball therapy with deciduous (puppy) teeth. There are two main reasons for this. Puppy teeth are fragile and can easily break. More importantly, the adult canine tooth bud is developing in the jaw medial to the deciduous canine tooth (see radiograph above in the puppy section). If the deciduous crown tips outwards the root will tip inwards. This will push the permanent tooth bud further medial than it already is.

Ball therapy will only work with adult teeth and only in some cases where the lower canines have a clear path to be tipped sideways - laterally - through the space between the upper third incisor and canine. The window of opportunity can be quite short, around 6 weeks, and starts when the lower canine teeth are almost making contact with the hard palate.

If you are considering ball therapy ask your vet their opinion and get them to send us images of each side of the closed mouth from the side with mouth closed and lips up.

The size and type of the ball or Kong is critical. The ball diameter should be the distance between the tips of the two lower canine teeth plus 50%. Therefore if this distance is 30mm the ball diameter is 45mm. If the ball is too small it will sit between the lower canines and produce no tipping force when the pup bites down. Too large a ball can intrude the lower canines back into their sockets.

The ball should "give" when the pup bites down. The smooth semi-hollow rubber is best. Tennis balls are abrasive and can damage the tooth surface but for a short time may do the job we require.

The owner needs to encourage play with the ball several times a day (6 - 8) or as often as they will tolerate with a short attention span. The ball should be only at the front of the mouth to go any good. If there are no positive results in six weeks a further veterinary evaluation is advised.

These permanent teeth can theoretically be treated by three options. Not all options are available to all cases. These options are described below and are either surgical removal of the lower canines teeth (and possibly incisors also), crown amputation and partial pulpectomy or orthodontics via an inclined bite plane bonded to the upper canines and incisors. The latter option may not be available to all dogs if the diastema (space) between the upper third incisor and canine is too small for the lower canines to move into or if the lower canines are located behind (palatal) to the upper canines.

This is a sterile procedure to reduce the height of the lower canine crown that exposes the pulp. It requires a removal of some pulp (partial coronal pulpectomy) and placement of a direct pulp capping.

This is a very delicate procedure and carries very high success rate (in our hands) since the availability of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA). We have used it as the material of choice since 2005. The previous agent (calcium hydroxide) was much more caustic and tended to "burn" the pulp. The success rate of MTA treated cases is quoted as 92% in a seminal ten year study based in vet dental clinics in Finland. This compares with 67% when caclium hydroxide was previously the agent. Luotonen N et al, JAVMA, Vol 244, No. 4, February 15, 2014 Vital pulp therapy in dogs: 190 cases (2001–2011).

The intention of the procedure is to keep the pulp alive and allow the shortened lower canines to develop normally and contribute to the strength of the lower jaws.

Radiograph left lower canine before (left) and immediately after (right) surgery. Note the immature morphology of the canine teeth - thin walls and open root apices.

In order to monitor this process of maturation we need to radiograph these teeth twice at 4-6 months post-op and again at 12 -16 weeks post-op. This is a mandatory check. The quoted success reate of 92% implies 8% failure. Half of those to fail in the Luotonen study happened over a year post-op. To ensure any failure of maturity is identified we will not perform this surgery unless the owner agrees to this.

The left radiograph shows the left lower canine immediately after crown amputation and partial pulpectomy. The right radiograph is same tooth 18 weeks post-op. Note the thicker dentine walls, development of an internal dentine bridge between pulp and direct pulp cap and the closed and matured root apex. These three criteria indicate a successful procedure at this stage.

The advantage of this procedure is that the whole of the root and the majority of the crown remain. The strength and integrity of the lower jaw is not weakened by the procedure and long term results are very good due to the use of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate as a direct pulp dressing.

Surgical extraction of the lower canine may seem attractive to clients as the problem is immediately dealt with without the uncertainties of orthodontics and the post-op check that is part of any crown amputation procedure.

However, many owners are concerned (rightly) about the loss of the tooth and the weakness it may cause to the lower jaw(s). It is not our preferred option. This is not an easy surgical extraction and the resulting loss of the root causes a weakness in the lower jaws. This is compounded if both lower canines are removed.

As this is an elective procedure (e.g. sterile) it is possible to use a bone allograft to fill the void created by the loss of the large canine tooth. The graft will promote new bone growth within a few weeks. Grafts can be very expensive as the void to be filled is large. This can increase the cost of the procedure markedly.

In some mild cases of lingual displacement we may be able to use crown extensions for a few weeks. For this treatment we bond composite resin extensions on the lower canines to increase the crown length by around 30%. This allows the lower canines to occupy the correct position and also provides more leverage to tip the crown tips buccally. The crown extensions remain in place for around 2 months and are then removed and the tooth surface smoothed and treated. The major downside is that if the dog damages or breaks them off, you need to return here for repairs. Sticks and other hard objects can easily cause damage and some toys also have to be withdrawn for the treatment period.

Orthodontic tipping as a treatment has the least certain outcome of all three option. It might seem less invasive than surgery but does require very careful case selection and management.

Normally a composite resin bite plane is bonded onto the upper teeth (see below) with an incline cut into the sides. The lower canine makes contact with the incline when the mouth closes and, over time, the force tips the tooth buccally. This takes around four to eight weeks. The lower canine will often migrate back into a lingually displaced position when the bite plane is removed. This can occur if the tooth height of the lower canine is too short (stunted). If the lower canine is not self-retained by the upper jaw when the mouth is shut further surgery may be required.

Orthodontic treatment will also conceal a defect and will not be performed unless the patient is neutered. In addition we have an ethical obligation to inform the Kennel Club of a change in conformation.

The images below show a lingually displaced left lower canine before treatment and after application of a bite plane. The bite plane remains in the mouth as long as it takes for the power of the bite to tip the lower canine into the normal position by pushing it up the incline.

Not all dogs or owners are suited to this. Bite planes can become dislodged if the dog bites a stick or other hard object. Bite planes also need cleaned and adjusted from time to time under sedation or anaesthesia. All of this means more travel and expense for you and more anaesthesia for your pet. It is our view that if a treatment has uncertain outcomes built in it should probably not be used.

Bite faults are one of the first hereditary defects a fledgling dog breeder learns to recognize. Teeth are right out there where everybody can take a look at them. Once you learn what is right for your breed, it isn’t difficult to recognize what is wrong. Though a dedicated cheat may “improve” a dog’s bite through orthodonture, there are limits to what can be done. For the most part, what you see is what you’ve got.

In order to fully understand bite faults, you must also understand what is correct and why. This goes beyond having the right number of the right teeth in the right places. A dog’s dental equipment is a direct inheritance from his wild carnivorous ancestor, the wolf. Dog dentition is also very similar to the wolf’s smaller cousin, the coyote. Figure 1 is a coyote skull, exhibiting a normal canine complement of teeth. Each jaw has six incisors at the front, followed by two canines, then eight premolars (four to a side). When we come to the molars, the top and bottom jaws differ. The lower jaw has six and the upper only four. A normal dog will have a total of 42 teeth.

Have you ever wondered how paleontologists know what a particular dinosaur did for a living? They look at the teeth. The number, shape, size and position of teeth will tell a lot about what that dinosaur’s diet was. If you know what it ate, you can draw some good conclusions about how it might have behaved.

We know what wolves and coyotes eat. The toolbox for delivering their self-serve meals is carried in their mouths. They don’t have a cat’s sharp, retractable claws and inward-turning wrists for grasping prey. Feet and legs get the wolf or coyote to the table, but they don’t serve the bacon. That must be done with the teeth and each type has a specific purpose.

The canines are most critical to catching and holding prey. Readers familiar with police K9s or Schutzhund will know that the preferred grip is a “full mouth bite:” The dog grasps the suspect’s arm or leg well into its mouth, between its molars and premolars and behind the canines. This is not the way a wolf does it.A wolf grips with the front of his mouth. The four canine teeth puncture the prey. Their overlapping structure (see Fig. 2)combined with jaw strength prevents the prey animal from pulling free. When catching bad guys, the idea isn’t to poke them full of holes and have them for dinner, but to hang on until the guy with the gun and the handcuffs arrives.

Once the prey is down, the premolars are used for biting off chunks of meat that are swallowed hole. The 4th upper premolar and the first lower molar on each side, the carnasals, are especially developed for this task. (Fig. 3) These are the most massive teeth in the canine jaw. They are very sharp and their location mid-way down the length of the jaw puts them at the point where jaw pressure is greatest.

The incisors, located at the front of the mouth, are for delicate work. They nibble the last bits of meat off bones and are also handy for scratching an itch or pulling something bothersome out of the coat or from between the pads.

, other than the lower carnasals, are flat for grinding plant matter. Wolves and coyotes will eat some amount of fruits, grasses and other plant matter. This food needs to be chewed a little to start the digestive process. Cats, by contrast, are strict carnivores. The only plant matter they eat is whatever happens to be inside the animal they are eating. Cats have no molars.

All these specialized teeth are not independent entities. Their position in the jaw is determined by their function and they require a properly formed skull and lower jaw to function efficiently. The muzzle must be long enough and broad enough to accommodate the teeth in their proper locations. The animal must have sufficient bite strength to hold onto whatever it has grabbed, be it prey or perpetrator. Jaw strength comes not only from the muscles, but the shape of the skull.

Figure 4shows the skulls of a coyote and an Australian Shepherd. Aussies have normally-shaped heads, so the shape of its skull is very similar to that of the coyote. The jaw muscles attach to the lower jaw and along the sagittal crest, the ridge of bone along the top and back of the skull. In between it passes over the zygomatic arch, or cheekbone. Wrapping around the cheekbone gives the bite much more strength than would a straight attachment from topskull to jaw. This attachment also serves to cushion the brain case from the flailing hooves of critters that don’t want to become dinner or get put in a pen.

You will note that the crest on the coyote is more pronounced than on the Aussie and its teeth are proportionally larger. This is a typical difference between domestic dogs and their wild kin. Wild canids need top efficiency from their dental equipment to survive. We have been providing food for our dogs for so long that the need for teeth as large and jaws as strong as their wolf ancestors has long passed.

Jaw strength is reduced in the dog by a less acute angle around the zygomatic arch. Note the more pronounced angle in the coyote (Fig. 5a) as compared to the Aussie (Fig. 5b).This is another typical difference between wolf or coyote and dog skulls. The larger sagital crest allows for a larger, and therefore stronger, muscle. The only breed with an angulation around the zygomatic arch that approaches that of the wolf is the American Pit Bull Terrier/American Staffordshire Terrier. Pit/AmStaffs also have a relatively short jaw, giving their heads a more cat-like structure: Broad + Short + Strong Muscles = Lots of Bite Strength.

Breeds with long, narrow heads have even straighter angulation around the cheekbone, and therefore an even weaker jaw. The narrow jaw may also cause crowding of the incisors. Toy breeds with round heads often have little or no sagittal crest and very weak jaws. Short-muzzled breeds may not have room for all their teeth resulting in malocclusion, meaning they don’t come together properly. The jaws of short-muzzled breeds may also be of unequal lengths.

The more we have altered skull and jaw shape from the norm, the less efficient the mouth has become. In some cases, this isn’t particularly important. There is no reason for a Collie or a Chihuahua to bite with the strength of a wolf. However, jaws that are so short it is impossible for all the teeth to assume normal positions and undershot bites that prevent proper occlusion of the canines and incisors are neither efficient nor functional, despite volumes of breed lore justifying those abnormalities in breeds where they are considered desirable.

For most breeds, like the Australian Shepherd, the skull shape has remained relatively normal. The short muzzle of the Pug and the undershot bite of a Bullmastiff, while quite acceptable in those breeds, would be deemed severe faults in Aussies and other normal-skulled breeds.

Now that we know what is “right,” for most breeds, anyway, and why it is right, let’s look at what can be wrong, why it is wrong and what, from a breeding standpoint, can be done about it. Most breeds with normal skull structure were originally developed to perform a function (herding, hunting, guarding, etc.) Since that structure is the most efficient it was maintained, with minor variations, in most functional breeds. Typical dental faults in these breeds are missing teeth and malocclusions. It is evident that these faults are inherited, but not a great deal is known about the specifics of that inheritance. In some breeds, some defects appear to have a simple mode of inheritance, but this is not the case across all breeds. That, plus the complex nature of dental, jaw and skull structure, indicates that in most cases the faults are likely to be polygenic, involving a group of genes.

Missing teeth obviously are not there to do the work they are intended for. They should be considered a fault. The degree of the fault can vary, depending on which teeth and how many are missing. The teeth most likely to be absent are premolars, though molars and sometimes incisors may occasionally fail to develop. Missing a first premolar, one of the smallest teeth, is much less a problem than missing an upper 4th premolar, a carnasial. The more teeth that are missing, the more faulty and less functional the bite becomes. If you have a dog with missing teeth, it should not be bred to other dogs with missing teeth or to the near relatives of such dogs. Though multiple missing teeth are not specifically faulted in either Australian Shepherd standard, you should think long and hard before using a dog that is missing more than a couple of premolars.

Malocclusions most frequently result from undershot and overshot bites, anterior crossbite and wry mouth. An undershot bite occurs when the lower jaw extends beyond the upper. This may happen because the lower jaw has grown too long or the upper jaw is too short. Selecting for shorter muzzles can lead to underbites. An overshot bite is the opposite, with the upper jaw longer than the lower. In either case, the teeth will not mesh properly. With slight over or undershot bites, the incisors may be the only teeth affected, but sometimes the difference in jaw length is extreme (Fig. 6)

leaving most or all of the teeth improperly aligned against those in the opposite jaw. A bite that is this far off will result in teeth that cannot be used at all, teeth that interfere with each other, improper wear and, in some cases, damage to the soft tissues of the opposite jaw by the canines.

In wry mouth, one side of the lower jaw has grown longer than the other, skewing the end of the jaw to one side. The incisors and canines will not align properly and may interfere. It is sometimes confused with anterior crossbite, in which some, but not all, of the lower incisors will extend beyond the upper incisors but all other teeth mesh properly.

Minor malocclusions, including “dropped” incisors and crooked teeth, also occur in some dogs. Dropped incisors are center lower incisors that are shorter than normal. Sometimes they will tip slightly outward and, when viewed in profile, may give the appearance of a bite that is slightly undershot. Dropped incisors tend to run in families and are therefore hereditary. Crooked teeth may be due to crowding in a too-small or too-narrow jaw or the result of damage to the mouth, though the former is more likely.

Some consider an even, or level, bite to be a type of malocclusion. Breed standards vary on whether they do or do not fault it. In the Australian Shepherd, the ASCA standard faults it while the AKC standard does not. There is clearly no consensus among dog people. Those who fault the even bite claim that it causes increased wear of the incisors, but there is little evidence to support this. A number of years ago the author, upon coming across a wolf with an even bite (Fig. 7), undertook a survey of wolf dentition. Teeth and jaws were inspected on 39 wolves, 9 of which were captive and the balance skulls of wild wolves trapped over a wide span of time and geography. Of the 39, 16 had even bites. This included five of the captive group, all of whom were related. Even discounting those, fully a third of the wild wolves had even bites. No structural fault is tolerated to this degree in a natural species, particularly in a feature so critical to the survival of that species.

As stated previously, bite faults and missing teeth are likely to be polygenic in inheritance. Each is also variable in the degree of fault between individuals. Dogs that have dental faults bad enough to be considered disqualifications under the breed standard ought not to be bred. Minor bite faults have only minimal impact on the dog’s ability to function. Before it is bred, the degree of a dog’s dental faults will have to be weighed along with all the other virtues and faults the dog has. If the dog is then considered worthy for breeding, it should not put to mates of similar pedigree (where genes for the fault clearly lurk,) or to mates from families where the its dental fault is known to occur. If, when being so bred, the faulty dog throws multiple offspring with the same dental fault, or produces affected pups with different mates, then it should probably be withheld from any further breeding.

The normal relatives of dogs with dental faults can be bred, but since they may carry some genes for the fault. If you own such a dog, you will want to select mates from families where this is not known to be a problem in order to reduce risk of perpetuating the fault.

So now you know not only whatcan be wrong with a bite, but why.Bite faults are one of the easier hereditary problems to deal with. Even if you are a relative beginner, with an understanding of dental structure and function you can evaluate the quality of not only your own dog’s dentition, but that of any other dogs whose mouths you might gaze into. Check out as many as you can and remember who has (or does not have) what and who they are related to. Armed with this knowledge, you can make informed breeding decisions for your own dogs.

An under bite (under shot, reverse scissors bite, prognathism, class 3) occurs when the lower teeth protrude in front of the upper jaw teeth. Some short muzzled breeds (Boxers, English Bull Dogs, Shih-Tzu’s, and Lhasa Apsos) normally have an under bite, but when it occurs in medium muzzled breeds it is abnormal. When the upper and lower incisor teeth meet each other edge to edge, the occlusion is considered an even or level bite. Constant contact between upper and lower incisors can cause uneven wear, periodontal disease, and early tooth loss. Level bite is considered normal in some breeds, although it is actually an expression of under bite.

Bite faults are one of the first hereditary defects a fledgling dog breeder learns to recognize. Teeth are right out there where everybody can take a look at them. Once you learn what is right for your breed, it isn’t difficult to recognize what is wrong. Though a dedicated cheat may “improve” a dog’s bite through orthodonture, there are limits to what can be done. For the most part, what you see is what you’ve got.

In order to fully understand bite faults, you must also understand what is correct and why. This goes beyond having the right number of the right teeth in the right places. A dog’s dental equipment is a direct inheritance from his wild carnivorous ancestor, the wolf. Dog dentition is also very similar to the wolf’s smaller cousin, the coyote. Figure 1 is a coyote skull, exhibiting a normal canine complement of teeth. Each jaw has six incisors at the front, followed by two canines, then eight premolars (four to a side). When we come to the molars, the top and bottom jaws differ. The lower jaw has six and the upper only four. A normal dog will have a total of 42 teeth.

Have you ever wondered how paleontologists know what a particular dinosaur did for a living? They look at the teeth. The number, shape, size and position of teeth will tell a lot about what that dinosaur’s diet was. If you know what it ate, you can draw some good conclusions about how it might have behaved.

We know what wolves and coyotes eat. The toolbox for delivering their self-serve meals is carried in their mouths. They don’t have a cat’s sharp, retractable claws and inward-turning wrists for grasping prey. Feet and legs get the wolf or coyote to the table, but they don’t serve the bacon. That must be done with the teeth and each type has a specific purpose.

The canines are most critical to catching and holding prey. Readers familiar with police K9s or Schutzhund will know that the preferred grip is a “full mouth bite:” The dog grasps the suspect’s arm or leg well into its mouth, between its molars and premolars and behind the canines. This is not the way a wolf does it, for reasons that will be explained shortly.

Fig 2 Note how the canines overlap and cross in their alignment. Wild canids, like this coyote, use the canines to grip their prey. The interlocking teeth prevent the prey from pulling free.

A wolf grips with the front of his mouth. The four canine teeth puncture the prey. Their overlapping structure (see Fig. 2,combined with jaw strength, prevents the prey animal from pulling free. When catching bad guys, the idea isn’t to poke them full of holes and have them for dinner, but to hang on until the guy with the gun and the handcuffs arrives

Once the prey is down, the premolars are used for biting off chunks of meat that are swallowed hole. The 4th upper premolar and the first lower molar on each side are especially developed for this task. (Fig. 3) The carnasals are the most massive teeth in the canine jaw. They are very sharp and their location mid-way down the length of the jaw puts them at the point where jaw pressure is greatest.

The incisors, located at the front of the mouth, are for delicate work. They nibble the last bits of meat off bones and are also handy for scratching an itch or pulling something bothersome out of the coat or from between the pads. Fig 3 The carnasals (fourth upper premolar and first lower molar) are the largest canine teeth, designed for shearing off chunks of meat. The molars, other than the lower carnasals, are flat for grinding.

Molars (Fig. 3), other than the lower carnasals, are flat for grinding plant matter. Wolves and coyotes will eat some amount of fruits, grasses and other plant matter. This food needs to be chewed a little to start the digestive process. Cats, by contrast, are strict carnivores. The only plant matter they eat is whatever happens to be inside the animal they are eating. Cats have no molars.

All these specialized teeth are not independent entities. Their position in the jaw is determined by their function and they require a properly formed skull and lower jaw to function efficiently. The muzzle must be long enough and broad enough to accommodate the teeth in their proper locations. The animal must have sufficient bite strength to hold onto whatever it has grabbed, be it prey or perpetrator. Jaw strength comes not only from the muscles, but the shape of the skull.

Figure 4 shows the skulls of a coyote and an Australian Shepherd. Aussies have normally-shaped heads, so the shape of its skull is very similar to that of the coyote. The jaw muscles attach to the lower jaw and along the sagittal crest, the ridge of bone along the top and back of the skull. In between it passes over the zygomatic arch, or cheekbone. Wrapping around the cheekbone gives the bite much more strength than would a straight attachment from topskull to jaw. This attachment also serves to cushion the brain case from the flailing hooves of critters that don’t want to become dinner or get put in a pen.

You will note that the crest on the coyote is more pronounced than on the Aussie and its teeth are proportionally larger. This is a typical difference between domestic dogs and their wild kin. Wild canids need top efficiency from their dental equipment to survive. We have been providing food for our dogs for so long that the need for teeth as large and jaws as strong as their wolf ancestors has long passed. Fig 5 Coyote (left) and Aussie (right). Note the straighter angulation around the zygomatic arch (cheekbone) of the Aussie. Jaw strength is reduced in the dog by a less acute angle around the zygomatic arch. Note the more pronounced angle in the coyote as compared to the Aussie. (Fig. 5) This is another typical difference between wolf or coyote and dog skulls. The larger sagital crest allows for a larger, and therefore stronger, muscle. The only breed with an angulation around the zygomatic arch that approaches that of the wolf is the American Pit Bull Terrier/American Staffordshire Terrier. Pit/AmStaffs also have a relatively short jaw, giving their heads a more cat-like structure: Broad + Short + Strong Muscles = Lots of Bite Strength.

Breeds with long, narrow heads have even straighter angulation around the cheekbone, and therefore an even weaker jaw. The narrow jaw may also cause crowding of the incisors. Toy breeds with round heads often have little or no sagittal crest and very weak jaws. Short-muzzled breeds may not have room for all their teeth resulting in malocclusion, meaning they don’t come together properly. The jaws of short-muzzled breeds may also be of unequal lengths.

The more we have altered skull and jaw shape from the norm, the less efficient the mouth has become. In some cases, this isn’t particularly important. There is no reason for a Collie or a Chihuahua to bite with the strength of a wolf. However, jaws that are so short it is impossible for all the teeth to assume normal positions and undershot bites that prevent proper occlusion of the canines and incisors are neither efficient nor functional, despite volumes of breed lore justifying those abnormalities in breeds where they are considered desirable.

For most breeds, like the Australian Shepherd, the skull shape has remained relatively normal. The short muzzle of the Pug and the undershot bite of a Bullmastiff, while quite acceptable in those breeds, would be deemed severe faults in Aussies and other normal-skulled breeds.

Now that we know what is “right,” for most breeds, anyway, and why it is right, let’s look at what can be wrong, why it is wrong and what, from a breeding standpoint, can be done about it. Most breeds with normal skull structure were originally developed to perform a function (herding, hunting, guarding, etc.) Since that structure is the most efficient it was maintained, with minor variations, in most functional breeds. Typical dental faults in these breeds are missing teeth and malocclusions. It is evident that these faults are inherited, but not a great deal is known about the specifics of that inheritance. In some breeds, some defects appear to have a simple mode of inheritance, but this is not the case across all breeds. That, plus the complex nature of dental, jaw and skull structure, indicates that in most cases the faults are likely to be polygenic, involving a group of genes.

Missing teeth obviously are not there to do the work they are intended for. They should be considered a fault. The degree of the fault can vary, depending on which teeth and how many are missing. The teeth most likely to be absent are premolars, though molars and sometimes incisors may occasionally fail to develop. Missing a first premolar, one of the smallest teeth, is much less a problem than missing an upper 4th premolar, a carnasal. The more teeth that are missing, the more faulty and less functional the bite becomes. If you have a dog with missing teeth, it should not be bred to other dogs with missing teeth or to the near relatives of such dogs. Though multiple missing teeth are not specifically faulted in either Australian Shepherd standard, you should think long and hard before using a dog that is missing more than a couple of premolars. Fig 6 Undershot bite. While the molars and some of the premolars occlude properly, the incisors and canines don"t even meet and are essentially useless. This is a farmed silver fox. Malocclusions this severe are extremely unusual in wild foxes. (photo courtesy Lisa McDonald) Malocclusions most frequently result from undershot and overshot bites, anterior crossbite and wry mouth. An undershot bite occurs when the lower jaw extends beyond the upper. This may happen because the lower jaw has grown too long or the upper jaw is too short. Selecting for shorter muzzles can lead to underbites. An overshot bite is the opposite, with the upper jaw longer than the lower. In either case, the teeth will not mesh properly. With slight over or undershot bites, the incisors may be the only teeth affected, but sometimes the difference in jaw length is extreme (Fig. 6) leaving most or all of the teeth improperly aligned against those in the opposite jaw. A bite that is this far off will result in teeth that cannot be used at all, teeth that interfere with each other, improper wear and, in some cases, damage to the soft tissues of the opposite jaw by the canines.

In wry mouth, one side of the lower jaw has grown longer than the other, skewing the end of the jaw to one side. The incisors and canines will not align properly and may interfere. It is sometimes confused with anterior crossbite, in which some, but not all, of the lower incisors will extend beyond the upper incisors but all other teeth mesh properly.

Minor malocclusions, including “dropped” incisors and crooked teeth, also occur in some dogs. Dropped incisors are center lower incisors that are shorter than normal. Sometimes they will tip slightly outward and, when viewed in profile, may give the appearance of a bite that is slightly undershot. Dropped incisors tend to run in families and are therefore hereditary. Crooked teeth may be due to crowding in a too-small or too-narrow jaw or the result of damage to the mouth, though the former is more likely.. Fig 7 Even (level) bite. This is a wolf. Some consider an even, or level, bite to be a type of malocclusion. Breed standards vary on whether they do or do not fault it. In the Australian Shepherd, the ASCA standard faults it while the AKC standard does not. There is clearly no consensus among dog people. Those who fault the even bite claim that it causes increased wear of the incisors, but there is little evidence to support this. A number of years ago the author, upon coming across a wolf with an even bite (Fig. 7), undertook a survey of wolf dentition. Teeth and jaws were inspected on 39 wolves, 9 of which were captive and the balance skulls of wild wolves trapped over a wide span of time and geography. Of the 39, 16 had even bites. This included five of the captive group, all of whom were related. Even discounting those, fully a third of the wild wolves had even bites. No structural fault is tolerated to this degree in a natural species, particularly in a feature so critical to the survival of that species.

As stated previously, bite faults and missing teeth are likely to be polygenic in inheritance. Each is also variable in the degree of fault between individuals. Dogs that have dental faults bad enough to be considered disqualifications under the breed standard ought not to be bred. Minor bite faults have only minimal impact on the dog’s ability to function. Before it is bred, the degree of a dog’s dental faults will have to be weighed along with all the other virtues and faults the dog has. If the dog is then considered worthy for breeding, it should not put to mates of similar pedigree (where genes for the fault clearly lurk,) or to mates from families where the it’s dental fault is known to occur. If, when being so bred, the faulty dog throws multiple offspring with the same dental fault, or produces affected pups with different mates, then it should probably be withheld from any further breeding.

The normal relatives of dogs with dental faults can be bred, but since they may carry some genes for the fault. If you own such a dog, you will want to select mates from families where this is not known to be a problem in order to reduce risk of perpetuating the fault.

So now you know not only what can be wrong with a bite, but why. Bite faults are one of the easier hereditary problems to deal with. Even if you are a relative beginner, with an understanding of dental structure and function you can evaluate the quality of not only your own dog’s dentition, but that of any other dogs whose mouths you might gaze into. Check out as many as you can and remember who has (or does not have) what and who they are related to. Armed with this knowledge, you can make informed breeding decisions for your own dogs.

I had a heck of a time finding any information on the internet in regards to the mode of inheritance for underbites. I have tried to research this subject given I have produced underbites in one of my lines My one vet seem to understand it say he understands the mode of inheritance very well so here is his explanation.

Just for the sake of those who do not understand how a recessive disorder works...it means that you need 2 copies of the gene instead of just one copy. Diseases or disorders that are dominantly expressed only need one copy. Recessive genes are always represented by "lowercase" letters and dominate genes by "capital" letter. Example would be the color chocolate. It is a "recessive color" which means it is represented by a lowercase "b" and you need 2 copies in order for the color to be expressed "bb". Dominate expression only needs one gene from either parent and are expressed as a "capital" letter. Just like the color Black is a dominate color and only needs one "B" for a pup to be Black.

OK...back to underbites. For the sake of example...let’s say that the 4 genes that control the degree of underbites is genes "w" "x" "y" and "z". The worst underbite like a Bulldog would be carrying "ww" "xx" "yy" "zz" A dog with NO underbite AND not carrying any recessive genes would be "WW" "XX" "YY" "ZZ".

Naturally I am not going to go into all the possible combinations or examples that could produce underbites as it would be too lengthy...but here are a few examples of different scenarios

Scenario 1 Dam has no Underbite but is carrying only one recessive gene ..let’s say she is "Ww" "XX" "YY" "ZZ" Sire has no underbite but is carrying only one recessive gene also..let’s say he is "WW " "XX" "Yy" "ZZ"

Result = NO pups with underbites but some may be carries of "w" and/or "y" Using the same example above lets" say the sire is also carrying "w" like the dam. Results = you COULD have a puppy with a slight underbite IF mom passed her "w" AND the dad passed his "w" also. The pups with the slight underbite would be "ww"

Scenarios 2) Dam HAS an SLIGHT Underbite and is NOT carrying other single recessives ..let’s say she is "ww" "XX" "YY" "ZZ" (she has an UNDEBITE because she is "ww") Sire has no underbite and is NOT carrying ANY recessive gene also..let’s say he is "WW " "XX" "YY" "ZZ"

Scenarios 3) Dam has no Underbite but is carrying several recessive genes ..let’s say she is "Ww" "Xx" "Yy" "ZZ" Sire has no underbite but is carrying several recessive gene also..let’s say he is "Ww " "Xx" "YY" "Zz"

An example of a Grade 2 would be a pup that inherited One "w" from both mom and dad and one "x" from both mom and dad which resulted in the pup being "ww" "xx" "YY" "ZZ" This pup could also be a carrier for "y" if mom passed her "y" instead of her "Y"

If you wanted to find out if your lines are carrying underbites...then perhaps breed to another known carrier. Problem with this type of test breeding is... BOTH dogs would have to be carrying some of the SAME recessives. If one dog is carrying "w" and "x" and the other is carrying "y" and "z"...you still will NOT have pups with underbites!

It"s those DANG recessives that end up being every breeders worst enemy! There is nothing worse than trying to eradicate something you can"t see especially when it involves several possible genes. These scenarios are similar to why 2 Parents with Excellent hips, but are carriers of various HD genes that can line up and can create HD pups.

Anyway...this is how Underbites were explained to me. I can"t prove if this explanation that was given to me is the gospel truth since I can"t find anything in my research. If anyone can come across modes of inheritance for underbites that can prove or disprove what I have shared...I would appreciate it if you can pass your info along .

There was no much attention paid until now to bite and teeth quality of Louisiana Catahoula. The reason is that Catahoula is the American breed and there is generally only a little attention focused on this matter. Both NALC standard, valid since 1977 (last revision in 1994) and UKC standard (2008) say that: „A scissors bite is preferred, but a level bite is acceptable. Full dentition is greatly desired, but dogs are not to be penalized for worn or broken teeth. Overshot or undershot bite are serious faults, but not disqualifying“. Catahoula is working breed and working qualities have been always more demanded than an ideal conformation and a superior bite. This is also the heritage we must deal with now.

Evaluation of European breeds and breeding was always more strict in this point of view and more focused on correct bite and full dentition, namely in breeds that preserve more or less normal skull parameters. Thus, scissor bite and full dentition is what most of breed standards demand and faults are more penalized. There is a good reason for it, because an efficient function needs a proper skull and jaw structure and teeth position. However, some anomalies were found also in wild living wolves and some faults are fairly common among various dog breeds even if not wanted.

Full dentition with all adult teeth fully erupted consist of incisors (Incisives – I), canines (Caninus – C), premolars (Praemolares – P), and molares (Molares – M). Upper and lower jaw differ in a number of molars. The teeth pattern is following:

In order to understand severity of dental faults it is good to know what is correct and why. A way how a wolf uses its teeth would be the best example to explain this matter. Concerning Catahoula, it a good example, too, because this breed has got most probably a red wolf among its ancestors. It could also support one of explanations of Schutzhund as a not very suitable activity for this breed that was mentioned by Anke Boysen elsewhere (https://www.ealc.info/en/working-dog-catahoula/).

In training and performing Schutzhund the preferred grip is a „full mouth bite“. The dog should grasp subject’s arm or leg well into its mouth, between its molars and premolars and behind the canines. This is not the way a wolf does it. A wolf grips with the front of his mouth. The four canine teeth puncture the prey and their overlapping structure combined with jaw strength prevents the prey from pulling free. Once the prey is down, the premolars are used for biting off chunk of meat. The upper P4 and the lower M1 on each side are especially developed for this task. The carnasals are the most massive teeth in the canine jaw. They are very sharp and their location mid-way down the length of the jaw puts them at the point where jaw pressure is greatest. The incisors located at the front of the mouth are specialized for delicate work. They nibble the last bits of meat off bones and are also handy for scratching an itch or pulling something bothersome out of the coat or from between the pads. Molars, other than mentioned, are flat for grinding plant matter. Wolves eat also some fruits, grasses and other plant matter and this type of food must be chewed a little to start digestive process.

All those specialized teeth have their proper position in the jaw, which is determined by their function, and they require a properly formed skull and lower jaw to function efficiently. The muzzle must be long enough and broad enough to accommodate the teeth in their proper locations. Jaw strength comes not only from the muscles, but the shape of the skull (1).

Most working breeds with normal skull mantained generally above mentioned dental structure, because it is the most efficient also for their work such as herding, hunting, etc. Nevertheless, missing teeth and malocclusions are typical dental faults in these breeds.

Research among wild wolves showed that the most frequent anomaly was the absence of the last molar in the lower jaw, M3. As it does not change the function, the absence of M3 should not be considered breeding deficiency also in dogs (2).

Missing teeth(hypodontia) is the fault observed often also in Catahoula breed. This fact and the degree of the fault should be evaluated according to which teeth and how many are missing. Some of premolars (P1, P2 or P3) and some of molars (M2, and most probably also M3) are most frequently among missing teeth. If the first premolar (P1), one of the smallest teeth, is missing, it is much less a problem than missing the upper P4 or M1 which belong to the most important teeth (see above). The more

8613371530291

8613371530291