overshot bite in dogs supplier

An overbite might not seem like a serious condition for your dog, but severely misaligned teeth can lead to difficulty eating, gum injuries and bruising, bad breath and different types of dental problems, including tooth decay and gingivitis. Fortunately, there are ways to help fix the problem before it becomes irreversible.

An overbite is a genetic, hereditary condition where a dog"s lower jaw is significantly shorter than its upper jaw. This can also be called an overshot jaw, overjet, parrot mouth, class 2 malocclusion or mandibular brachynathism, but the result is the same – the dog"s teeth aren"t aligning properly. In time, the teeth can become improperly locked together as the dog bites, creating even more severe crookedness as the jaw cannot grow appropriately.

This problem is especially common in breeds with narrow, pointed muzzles, such as collies, shelties, dachshunds, German shepherds, Russian wolfhounds and any crossbred dogs that include these ancestries.

Dental examinations for puppies are the first step toward minimizing the discomfort and effects of an overbite. Puppies can begin to show signs of an overbite as early as 8-12 weeks old, and by the time a puppy is 10 months old, its jaw alignment will be permanently set and any overbite treatment will be much more challenging. This is a relatively narrow window to detect and correct overbites, but it is not impossible.

Small overbites often correct themselves as the puppy matures, and brushing the dog"s teeth regularly to prevent buildup can help keep the overbite from becoming more severe. If the dog is showing signs of an overbite, it is best to avoid any tug-of-war games that can put additional strain and stress on the jaw and could exacerbate the deformation.

If an overbite is more severe, dental intervention may be necessary to correct the misalignment. While this is not necessary for cosmetic reasons – a small overbite may look unsightly, but does not affect the dog and invasive corrective procedures would be more stressful than beneficial – in severe cases, a veterinarian may recommend intervention. There are spacers, braces and other orthodontic accessories that can be applied to a dog"s teeth to help correct an overbite. Because dogs" mouths grow more quickly than humans, these accessories may only be needed for a few weeks or months, though in extreme cases they may be necessary for up to two years.

If the dog is young enough, however, tooth extraction is generally preferred to correct an overbite. Puppies have baby teeth, and if those teeth are misaligned, removing them can loosen the jaw and provide space for it to grow properly and realign itself before the adult teeth come in. Proper extraction will not harm those adult teeth, but the puppy"s mouth will be tender after the procedure and because they will have fewer teeth for several weeks or months until their adult teeth have emerged, some dietary changes and softer foods may be necessary.

An overbite might be disconcerting for both you and your dog, but with proper care and treatment, it can be minimized or completely corrected and your dog"s dental health will be preserved.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Photos of “dogs with underbites” have been the focus of many an adorable Internet slideshow. But while misaligned teeth in dogs, or canine malocclusion, may make our pets seem more endearing or “ugly-cute,” it can be a serious health issue.

To learn more about this condition, we spoke with two board-certified veterinary dentists from the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine (CUCVM). Here is everything you need to know about canine malocclusion, including symptoms and causes, and when to seek treatment.

Canine malocclusion simply refers to when a dog’s teeth don’t fit together properly, whether it’s his baby teeth or adult teeth. Determining whether a dog suffers from malocclusion can be tricky because, unlike with humans, there’s no standard way a dog’s bite should look. “The dimensions and bite configuration of every dog are so different,” says Dr. Santiago Peralta, assistant professor of veterinary dentistry and oral surgery at CUCVM. “The big question is not whether it’s ‘normal,’ but more so: is it functionally comfortable for the animal?”

So, what makes for a comfortable bite? In general, “The lower canines should be sitting on the outside of the gum line and in front of the upper canines,” explains Dr. Nadine Fiani, assistant clinical professor of dentistry and oral surgery at CUCVM. “One of the most common abnormalities that we see is where the lower canine is so upright that it actually barges up into the hard palate.” Basically, if your dog has tooth-to-tooth contact or tooth-to-soft tissue contact that shouldn’t be there, that’s clinically relevant malocclusion, she says, and it is sometimes accompanied by erosion or trauma to teeth or tissue.

While clients and breeders may use descriptors like “underbite” or “overbite,” Peralta and Fiani don’t use these terms in their practice. “The meaning of each of those terms may vary depending on who you ask. And because it’s subjective lay-terminology, it potentially can be very confusing,” Peralta says. Veterinary dentists rely instead on technical nomenclature, like that preferred by the American Dental Veterinary College (ADVC), in making their diagnoses and considering treatment.

The big question on a dog owner’s mind when it comes to any health issue is, of course, how can I tell ifmydog is suffering? In the case of canine malocclusion, it won’t be obvious—just because your dog appears to have an underbite doesn’t mean he is experiencing pain or discomfort. Sometimes, a veterinarian may note a malocclusion in a puppy at the time of vaccination, Fiani says. But otherwise, you’ll need to observe your dog’s behavior and bite, and bring any issues to your vet’s attention. “The reality is, most dogs that have some kind of malocclusion will have had it for the vast majority of their life,” she says, “and so often, they will be in pain, but they may not necessarily overtly show that.”

If your dog is indeed in pain, he or she might engage in subtle behavior changes such as acting “head-shy” (recoiling when you pet her on the head or face), rubbing her head against the wall or with her paws, or demonstrating difficulty picking up or chewing food, Peralta explains. Physical symptoms of malocclusion may include unusually bad breath or bloody drool.

Any changes in behavior or physical health—even subtle ones—are worth checking out, since untreated malocclusion can have very painful consequences. Fiani cites oronasal fistula as one of the most severe side effects, which is when an abnormal communication (or hole) forms between mouth and nose as a result of a lower canine that is too vertically positioned. This can lead to not only great pain and discomfort, but also possible nasal disease. And if a malocclusion involves teeth that are crowded together, Fiani says, this can cause a buildup of plaque and, eventually, gingivitis or gum disease.

In broad terms, malocclusions are either skeletal or dental in origin, Fiani explains. A dental origin is when a dog may have “one or a couple of teeth that are abnormally positioned within a normal facial skeletal structure,” and are causing pain or discomfort.

The skeletal type of malocclusion, Fiani notes, is where the facial skeleton is abnormal, causing the teeth not to fit together properly. For example, the “underbite” affects short-faced breeds like Bulldogs and Boxers, which have malformed skulls because of breeding. (Long-faced breeds like Sighthounds are prone to similar issues.)

While breeding can have an impact, there is a range of potential causes for either type of malocclusion. “Malocclusions can have a genetic basis that will be likely transmitted from generation to generation,” Peralta says, “and some of them will be acquired, whether because something happened during gestation or something happened during growth and development, either an infection or trauma or any other event that may alter maxillofacial [face and jaw] growth.” He explains that trauma to the face and jaw can stem from events like being bitten by another animal or getting hit by a car. Fiani adds that jaw fractures that don’t heal properly can also result in malocclusion.

“It doesn’t always exactly matter why there’s a malocclusion, the question is: do you need to treat it?” Fiani says. “The bottom line is, if you have abnormal tooth-to-tooth contact or if you have abnormal tooth-to-soft tissue contact, then something has to be done about it.” If you notice any of the previously mentioned signs, it’s time to consult with your veterinarian, who will typically determine whether a referral to a dental specialist is warranted for further assessment. If you’ve got an image-obsessed hound, let’s be clear: veterinary dentists treat medical issues, not cosmetic ones. “We will not perform any sort of orthodontic treatment on an animal for aesthetic purposes,” Fiani emphasizes. “There has to be a clear-cut medical reason for preventing disease or prevention of discomfort or pain.”

Treatment options will vary depending on the specific issue facing your dog, his age, and other factors, but typically will fall into one of two categories: extraction or orthodontic treatment. Tooth extractions can be performed by your general practitioner or a dental specialist, depending, Fiani says, but orthodontics is always the purview of specialists. “That’s really when we’re using appliances to try and shift the teeth around so that they fit together in a way that no longer hurts the dog,” she explains.

So, if your dog is known for his quirky underbite, it’s probably a good idea to seek medical advice. It can be difficult to tell if malocclusion is causing issues, so don’t be afraid to ask your veterinarian questions, and pay close attention to your dog’s health and behavior. The bottom line is that, left untreated, malocclusion can lead to more than just an off-kilter smile—it can result in a painful life for your pooch.

Normally, a puppy will have 28 baby teeth once it is six months old. By the time it reaches adulthood, most dog breeds will have 42 teeth. A misalignment of a dog"s teeth, or malocclusion, occurs when their bite does not fit accordingly. This may begin as the puppy"s baby teeth come in and usually worsens as their adult teeth follow.

The smaller front teeth between the canines on the upper and lower jaws are called incisors. These are used to grasp food and to keep the tongue inside the mouth. Canines (also known as cuspids or fangs) are found behind the front teeth, which are also used to grasp. Behind the canines are the premolars (or bicuspids) and their function is to shear or cut food. Molars are the last teeth found at the back of the mouth and they are used for chewing.

If problems with the palate persist, a fistula may result and become infected. In cases of misaligned teeth (or malocclusion), the dog may have difficulty chewing, picking up food, and may be inclined to eat only larger pieces. They are also prone to tartar and plaque build-up.

The tips of the premolars (the teeth right behind the canines) should touch the spaces between the upper premolars, which is called the scissor bite. However, it is normal for flat-faced breeds (brachycephalic) such as Boxers, Shih Tzus, and Lhasa Apsos not to have scissor bites.

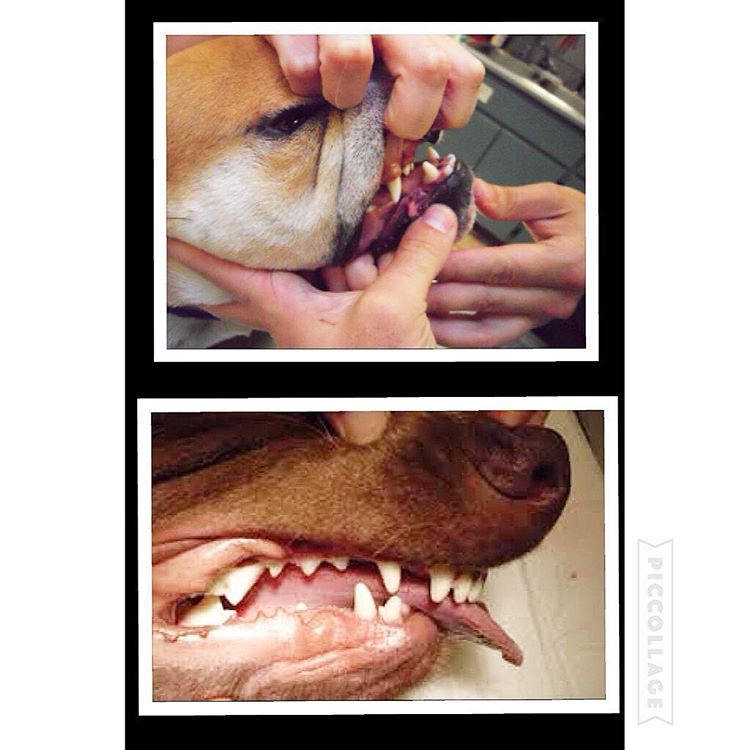

With an overbite, the upper jaw is longer than the lower one. When the mouth is closed, a gap between the upper and lower incisors occurs. Puppies born with an overbite will sometimes have the problem correct itself if the gap is not too large. However, a dog"s bite will usually set at ten months old. At this time improvement will not happen on its own. Your pet"s overbite may worsen as the permanent teeth come in because they are larger and can damage the soft parts of the mouth. Teeth extractions are sometimes necessary.

The way the upper teeth align with the lower teeth is called occlusion. It is normal for most breeds to have a slight overlap of the upper front teeth. When the jaw is closed, the lower canine (fang) should fit in front of the upper canine. Most cases of malocclusion have a hereditary link.

Most bite malocclusions do not require treatment. In some cases, extractions may be necessary. It’s a good idea to brush the teeth regularly to prevent abnormal build-up of tartar and plaque. Your veterinarian will sometimes recommend a dental specialist if you want to correct the teeth misalignment. In recent years, “braces” have been made for puppies to realign the teeth.

This condition is most often spotted at either the first or second puppy checks or between 6 and 8 months of age as the permanent (adult) teeth erupt. Either the deciduous or permanent lower canines occlude into the soft tissues of the roof or the mouth causing severe discomfort and, possibly, oral nasal fistulae.

The fact sheet answers many questions you may have about the cause of this problem and the various treatments available. It is important not to delay treatment of deciduous lower canines as the window of opportunity is only a matter of a few weeks until the permanent canines erupt at 22 to 26 weeks of age. A new problem can then present with bigger teeth causing more damage.

We advise you email us images of the teeth (mouth closed, lips up and side on for both left and right) just a few days before you travel. Things change quickly in growing dogs and it might save you a wasted journey.

This is an inherited condition - an autosomal recessive mutation. Both parents may look normal but carry recessive genes for the condition. When this genetic information is passed onto the litter, approximately one pup in four will be affected, appear abnormal and can pass the genetic information on if bred from. In addtion, two pups in four will carry an abnormal gene from one parent and a normal gene from the other. This pups will look normal but can pass the problem on if bred. Finally one pup in four will not be a carrier of abnormal genes, will be unaffected and cannot pass the trait on to future generations.

If this condition appears in the litter, the most responsible course of action is not to breed from the parents again - either as a pair or individually with others. As there is currently no test to identify this gene, selecting another mate may mean they too are recessive carriers. All the normal looking sibling pups are likely to also carry the recessive genes. It is wise that they too do not contribute to passing the problem back into the breed"s gene pool. In many affected breeds, the gene pool of breeding individuals to select from is very small. If recessive carriers are routinely mating then it is not long before increasing numbers of pups appear with this condition. Over four decades we have monitored the breeds treated here and it is disappointing to note that many previously unaffected breeds are now being seen on a regular basis.

When a pup is treated for this condition we routinely supply the Kennel Club with a Change of Conformation form so they can track the parental origin. We also ask for permssion to send a DNA swab to the Animal Health Trust. This is anonymously evaluated as part of a research programme to identify the exact genetic origin of the condition with the aim of a simple test becoming available to identify recessive carriers. In time this will allow owners of known recessive carriers to select a mate unaffected by the condition.

Owners with young puppies identified with this problem at first presentation are advised to have the deciduous lower canines removed as soon as possible. There are three reasons for this:

Firstly, and most importantly, these teeth are sharp and hitting the soft tissues of the palate. These pups cannot close their mouth without pain and often hold the mouth slightly open to avoid contact. This is not pleasant. See above for an example of the damage caused to the hard palate by this problem.

Secondly, the growth of the mandible is rostral from the junction of the vertical and horizontal ramus. If the lower canines are embedded in pits in the hard palate, the normal rostral growth of the mandible(s) cannot take place normally due to the dental interlock caused by the lower canines being embedded in hard palate pits. This can cause deviation of the skull laterally or ventral bowing of the mandibles (lower jaws).

Thirdly, the permanent lower canine is located lingual to the deciduous canine. This means that if the deciduous lower canines are in a poor position it is a certainty the permanent teeth will be worse. See the radiograph below. The deciduous canines are on the outside of the jaws and the developing permanent canines are seen in the jaw as small "hats". It is clear that the eruption path of the permanent canines will be directly dorsal and not buccally inclined as is normal.

For these three reasons it is advisable to surgically remove the lower canine teeth as soon as possible to allow maximum time between the surgery and the time the permanent teeth erupt at between 22 and 24 weeks of age. See our file for illustration of removal of deciduous canines.

The deciduous tooth root is three to four times longer than the visible crown and curved - often 2.5cm in length and curved. The root apex is often located below the third lower premolar. See middle and right images below with extracted deciduous tooth laid over extraction site.

The roots are very fragile and will break easily if unduly stressed during removal. A broken root needs to be identified and removed otherwise it continues to form a barrier to the eruption path of the permanent canine and can cause local infection.

The permanent successor tooth is located lingual to the deciduous tooth and wholly within the jaw at this stage. Any use of luxators or elevators on the lingual half of the deciduous tooth will cause permanent damage to the developing enamel of the permanent tooth. See the images below showing canines (and also the third incisor) with extensive damage to the enamel. The radiograph also shows how much damage can occur to the teeth - see the top canine and adjacent incisor. Some severely damaged teeth need to be extracted while other can be repaired with a bonded composite. This damage is avoidable with careful technique using an open surgical approach.

Surgery to remove the deciduous canines may not prevent to need for surgery on the permanent canines but, without it, few cases will resolve if left to nature. Many owners are reluctant to have young pups undergo surgery. Our view is that surgical removal of the lower deciduous canines will not guarantee the problem does not happen again when the permanent teeth erupt but without surgery the chances are very slim.

In a few selected cases - usually only very mild lingual displacement - we can consider placing crown extensions on the lower canines to help guide them into a more natural position. It carries some uncertainly and will not be suited or work in all cases. The images below show crown extensions on a young Springer Spaniel.

Please note that the use of a rubber ball to assist tipping of the deciduous lower canines buccally is not appropriate at this age and will not work - see below.

If the permanent teeth are lingually displaced the pup is usually older than 24 weeks. The trauma caused by the teeth on the soft tissues can be considerable with pain as a consequence.

Do not try ball therapy with deciduous (puppy) teeth. There are two main reasons for this. Puppy teeth are fragile and can easily break. More importantly, the adult canine tooth bud is developing in the jaw medial to the deciduous canine tooth (see radiograph above in the puppy section). If the deciduous crown tips outwards the root will tip inwards. This will push the permanent tooth bud further medial than it already is.

Ball therapy will only work with adult teeth and only in some cases where the lower canines have a clear path to be tipped sideways - laterally - through the space between the upper third incisor and canine. The window of opportunity can be quite short, around 6 weeks, and starts when the lower canine teeth are almost making contact with the hard palate.

If you are considering ball therapy ask your vet their opinion and get them to send us images of each side of the closed mouth from the side with mouth closed and lips up.

The size and type of the ball or Kong is critical. The ball diameter should be the distance between the tips of the two lower canine teeth plus 50%. Therefore if this distance is 30mm the ball diameter is 45mm. If the ball is too small it will sit between the lower canines and produce no tipping force when the pup bites down. Too large a ball can intrude the lower canines back into their sockets.

The ball should "give" when the pup bites down. The smooth semi-hollow rubber is best. Tennis balls are abrasive and can damage the tooth surface but for a short time may do the job we require.

The owner needs to encourage play with the ball several times a day (6 - 8) or as often as they will tolerate with a short attention span. The ball should be only at the front of the mouth to go any good. If there are no positive results in six weeks a further veterinary evaluation is advised.

These permanent teeth can theoretically be treated by three options. Not all options are available to all cases. These options are described below and are either surgical removal of the lower canines teeth (and possibly incisors also), crown amputation and partial pulpectomy or orthodontics via an inclined bite plane bonded to the upper canines and incisors. The latter option may not be available to all dogs if the diastema (space) between the upper third incisor and canine is too small for the lower canines to move into or if the lower canines are located behind (palatal) to the upper canines.

This is a sterile procedure to reduce the height of the lower canine crown that exposes the pulp. It requires a removal of some pulp (partial coronal pulpectomy) and placement of a direct pulp capping.

This is a very delicate procedure and carries very high success rate (in our hands) since the availability of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate (MTA). We have used it as the material of choice since 2005. The previous agent (calcium hydroxide) was much more caustic and tended to "burn" the pulp. The success rate of MTA treated cases is quoted as 92% in a seminal ten year study based in vet dental clinics in Finland. This compares with 67% when caclium hydroxide was previously the agent. Luotonen N et al, JAVMA, Vol 244, No. 4, February 15, 2014 Vital pulp therapy in dogs: 190 cases (2001–2011).

The intention of the procedure is to keep the pulp alive and allow the shortened lower canines to develop normally and contribute to the strength of the lower jaws.

Radiograph left lower canine before (left) and immediately after (right) surgery. Note the immature morphology of the canine teeth - thin walls and open root apices.

In order to monitor this process of maturation we need to radiograph these teeth twice at 4-6 months post-op and again at 12 -16 weeks post-op. This is a mandatory check. The quoted success reate of 92% implies 8% failure. Half of those to fail in the Luotonen study happened over a year post-op. To ensure any failure of maturity is identified we will not perform this surgery unless the owner agrees to this.

The left radiograph shows the left lower canine immediately after crown amputation and partial pulpectomy. The right radiograph is same tooth 18 weeks post-op. Note the thicker dentine walls, development of an internal dentine bridge between pulp and direct pulp cap and the closed and matured root apex. These three criteria indicate a successful procedure at this stage.

The advantage of this procedure is that the whole of the root and the majority of the crown remain. The strength and integrity of the lower jaw is not weakened by the procedure and long term results are very good due to the use of Mineral Trioxide Aggregate as a direct pulp dressing.

Surgical extraction of the lower canine may seem attractive to clients as the problem is immediately dealt with without the uncertainties of orthodontics and the post-op check that is part of any crown amputation procedure.

However, many owners are concerned (rightly) about the loss of the tooth and the weakness it may cause to the lower jaw(s). It is not our preferred option. This is not an easy surgical extraction and the resulting loss of the root causes a weakness in the lower jaws. This is compounded if both lower canines are removed.

As this is an elective procedure (e.g. sterile) it is possible to use a bone allograft to fill the void created by the loss of the large canine tooth. The graft will promote new bone growth within a few weeks. Grafts can be very expensive as the void to be filled is large. This can increase the cost of the procedure markedly.

In some mild cases of lingual displacement we may be able to use crown extensions for a few weeks. For this treatment we bond composite resin extensions on the lower canines to increase the crown length by around 30%. This allows the lower canines to occupy the correct position and also provides more leverage to tip the crown tips buccally. The crown extensions remain in place for around 2 months and are then removed and the tooth surface smoothed and treated. The major downside is that if the dog damages or breaks them off, you need to return here for repairs. Sticks and other hard objects can easily cause damage and some toys also have to be withdrawn for the treatment period.

Orthodontic tipping as a treatment has the least certain outcome of all three option. It might seem less invasive than surgery but does require very careful case selection and management.

Normally a composite resin bite plane is bonded onto the upper teeth (see below) with an incline cut into the sides. The lower canine makes contact with the incline when the mouth closes and, over time, the force tips the tooth buccally. This takes around four to eight weeks. The lower canine will often migrate back into a lingually displaced position when the bite plane is removed. This can occur if the tooth height of the lower canine is too short (stunted). If the lower canine is not self-retained by the upper jaw when the mouth is shut further surgery may be required.

Orthodontic treatment will also conceal a defect and will not be performed unless the patient is neutered. In addition we have an ethical obligation to inform the Kennel Club of a change in conformation.

The images below show a lingually displaced left lower canine before treatment and after application of a bite plane. The bite plane remains in the mouth as long as it takes for the power of the bite to tip the lower canine into the normal position by pushing it up the incline.

Not all dogs or owners are suited to this. Bite planes can become dislodged if the dog bites a stick or other hard object. Bite planes also need cleaned and adjusted from time to time under sedation or anaesthesia. All of this means more travel and expense for you and more anaesthesia for your pet. It is our view that if a treatment has uncertain outcomes built in it should probably not be used.

Does your dog have a toothy grin that pops out when they are relaxed? This could be an "underbite" which is fairly common among dogs. However, depending on the severity of the "grin" could have underlying health problems.

The way a dog"s teeth should line up together is called a "scissor bite".A dog who"s teeth don"t quite fit straightly together, and the bottom jaw"s teeth protrude further than the upper jaw has what is called an underbite, also known as Canine Malocclusion.

This is a feature most often seen in short muzzled dogs like pugs, terriers, cavaliers, shih-tzu, boxers and bulldogs, however any mix breed dog with a parent from a breed that is known to develop an underbite has a greater likelihood of inheriting an underbite.

In humans it is easy to see if we have developed an underbite. In dogs however it is a little harder to see from what is "normal" as a dogs jaw is different to our own. The way you can tell if your dog has an underbite is when they are most at rest and relaxed as their bottom teeth will poke out from under their lips.

If your dog has no issues with chewing solid foods, and they can move their jaw comfortably and bite well enough, then there is nothing to worry about. As noted earlier this is a fairly common trait in dog breeds with short muzzles and "flat faces".

Skeletal Malocclusion - this is seen in pedigrees usually in a short muzzled breed (but can also occur in long snouted breeds like sight hounds), where the lower jaw is longer than the upper jaw due to a skull abnormality resulting in the two jaws not lining up properly.

However, any breed of dog can develop an underbite. This can occur when a pups baby teeth have fallen out and a new set start to develop at an angle. This is typically around the 10 month marker. For a dog who has breeds that typically develop an underbite, this should not affect the dog.

If a dog develops Dental Malocclusion there could be a few problems for the pup. Such as tooth-to-tooth-contact or tooth-to-gum-contact where there shouldn"t be. This is due to bad teeth alignment and can affect a dog"s normal mouth functions such as eating, chewing, cleaning and biting as this unwanted contact can cause a dog much distress.

This unusual teeth placement can cause unseen issues such as cuts to the dog"s lips, cheek tissues and may cause mouth ulcers, infections and tooth decay. A vet should notice any problems in a check up. They will then determine if further action is required.

The vast majority of skeletal malocclusion requires no treatment. This is also the same for dental malocclusion, it is only if it causes a sever risk to the dog - such as bad teeth formation or an underlying dental issues that cause the dog pain that further action should be taken. Your vet will be able to advise you if this is the case when your dog has a check up.

It has also been noted that some puppies that developed an underbite in their early years "grow" out of it as their face and jaw begin to take form as they develop into dogs. Although it varies from breed to breed, a dog"s facial alinement is often determined around 10 months of age.

You can download this article on puppy teeth problems as an ebook free of charge (and no email required) through the link below. This comprehensive article covers such topics as malocclusions, overbites, underbites and base narrow canines in dogs. Special emphasis is placed on early intervention – a simple procedure such as removing retained puppy teeth can save many problems later on.

One of the biggest misconceptions is that dental problems don’t need the same treatment in animals as they do in humans. Nothing could be further from the truth! Dogs’ teeth have the same type of nerve supply in their teeth as we do, so anything that hurts us will hurt them as well.

All dogs, whether they are performance dogs or pets, deserve to have a healthy, pain-free mouth. Oral and dental issues frequently go undiagnosed in dogs, partly because the disease is hidden deep inside the mouth, and partly because dogs are so adept at hiding any signs of pain. As a pack animal, they don’t want to let the rest of the pack (including us!) know they have a problem, as anything that limits their usefulness to the pack may be grounds for exclusion. This is a survival instinct. Dogs will suffer in silence for as long as they can, and they only stop eating when they cannot bear the pain any longer.

This article has been written to help you understand how oral and dental problems develop in puppies, what the implications of these issues are, and what options are available to you and your pup to achieve the best outcomes in terms of overall health, comfort and performance. You don’t need to read it from top to bottom, as your dog would need to be pretty unlucky to need all the advice included here!

However, I do recommend that you look through the information on what a ‘normal’ mouth is, as this will help you to understand how each problem can arise.

baby) teeth which erupt between 3-8 weeks of age. These are replaced by the adult (permanent) teeth between 4-7 months of age. Adult dogs should have a total of 42 teeth. The difference in the number of deciduous and adult teeth arises because some adult teeth (the molars and first premolars) don’t have a deciduous version.

The way the teeth align with each other is referred to as the ‘occlusion’. Normally the upper incisors sit just in front of the lower incisors, this is called a ‘scissor bite’. The lower canines sit in the gap between the upper canines and corner (third) incisors, without rubbing against either of these teeth.

Although a scissor bite is standard for most breeds, in some breeds with a short, wide muzzle (brachycephalic skull type), a reverse scissor bite is accepted as the breed standard, where the upper incisors are behind the lower ones, and the lower canines are shifted forward. A level bite (where the upper and lower incisors are in line with each other) is also acceptable in some breeds.

The points of the smaller lower premolars should point to the spaces between the upper premolars, with the lower first premolar being the first from the front. The upper carnassial tooth should sit outside the lower carnassial tooth.

The bulk of the tooth is made up of dentine (or dentin), a hard bony-like material with tiny dentinal tubules (pores) running from the inside to the outside. In puppies, the dentine is relatively thin, making the tooth more fragile than in an older dog. The dentine thickens as the tooth matures throughout life.

The crown is covered in enamel, which is the hardest material in the body (even harder than bone!). This is only made prior to eruption, and cannot be regenerated if damaged.

Inside the tooth is the pulp, which is living tissue containing blood vessels, nerves and immune cells. The nerves have processes which extend through the dentinal tubules, and if these are exposed or stimulated they can cause sensitivity or intense pain.

Malocclusion is the termed used for an abnormal bite. This can arise when there are abnormalities in tooth position, jaw length, or both. The simplest form of malocclusion is when there are rotated or crowded teeth. These are most frequently seen in breeds with shortened muzzles, where 42 teeth need to be squeezed into their relatively smaller jaws. Affected teeth are prone to periodontal disease (inflammation of the tissues supporting the teeth, including the gums and jawbone), and early tooth loss.

Crowded upper incisor teeth in an English Bulldog, with trapping of food and debris. There is an extra incisor present which is exacerbating the problem.

Anterior (rostral) crossbite occurs when one or more upper incisors are positioned behind their lower counterparts. Constant striking of the lower incisors and oral tissues by the upper teeth may result in periodontal disease, pulpitis (inflammation of there sensitive living pulp tissue inside the teeth) and early tooth loss

‘Base narrow’ canines (Linguoverted or ‘inverted’ canines) are a relatively common and painful problem in Australian dogs. The lower canines erupt more vertically or ‘straight’ than normal (instead of being tilted outwards), and strike the roof of the mouth. This causes pain whenever the dog chews or closes its mouth, and can result in deep punctures through the palatal tissues (sometimes the teeth even penetrate into the nasal cavity!). In our practice in Sydney, we see this most commonly in Staffordshire Bull Terriers and Labrador Retrievers.

Lance’ canines (Mesioverted, hard or ‘spear’ canines) occur when an upper canine erupts so it is pointing forward, like a tusk. This is seen most commonly in Shetland Sheepdogs, and can lead to lip trauma and displacement of the lower canine tooth (which cannot erupt to sit in its normal position in front of the upper canine).

Class II malocclusions (‘overshot’) arise when the lower jaw is relatively short compared with the upper jaw. This type of occlusion is NEVER considered normal and can result in significant and painful trauma to the upper gums, hard palate and teeth from the lower canines and incisors.

Class III malocclusions (‘undershot’, ‘prognathism’) occur when the lower jaw is relatively long compared with the upper jaw. The upper incisors may either meet the lower ones (level bite) or sit behind them (reverse scissor bite). While this is very common, and considered normal for some breeds, it can cause problems if the upper incisors are hitting the floor of the mouth or the lower teeth (similar problems to rostral crossbite). If the lower canines are striking the upper incisors, the accelerated dental wear often results in dead or broken teeth.

Class IV malocclusions (‘wry bite’) occur when there is a deviation of one or both jaws in any direction (up and down, side to side or front to back). These may be associated with mild to severe problems with chewing, damage to teeth and oral tissues, and chronic pain.

Normal development of the teeth and jaws is largely under genetic control, however environmental forces such as nutrition, trauma, dental interlock and other mechanical forces can also affect the final outcome.

As the interaction between these factors can be quite complex, it is recommended that you have your pup individually assessed – feel welcome to call me for advice.

Most malocclusions involving jaw length (skeletal) abnormalities are genetic in origin. We need to recognise this as it has enormous implications if you are planning to breed, as once a malocclusion is established in a line, it can be heartbreaking work to try and breed it back out.

The exact genes involved in jaw development are not yet well understood. We do know that the upper and lower jaws grow at different rates, at different times, and are under separate genetic control. In fact, the growth of one only affects the growth of the other if there is physical contact between them via the teeth. This contact is called ‘dental interlock’.

When the upper and lower teeth are locked against each other, the independent growth of either jaw is severely limited. This can occasionally work in the dog’s favour, for example if the lower jaw is slightly long compared with the upper jaw, the corner incisors may lock the lower canines in position behind them, limiting any further growth spurts of the lower jaw.

However, in many cases, dental interlock interferes with jaw development in a negative way. A classic example we see regularly in our practice is when a young puppy has a class II malocclusion (relatively short lower jaw) and the lower deciduous canines are locked behind the upper deciduous canines, or trapped in the tissues of the hard palate. In these cases, even if the lower jaw was genetically programmed to catch up to the upper jaw, it cannot physically do so.

Early removal of the lower canines (and often the lower incisors as well) to relieve this problem is strongly recommended. This procedure is called ‘interceptive orthodontics’ as we are ‘intercepting’ the developing problem before growth is completed and it is too late.

Extraction of these teeth will not stimulate jaw growth, but will allow it to occur if nature (ie genetic potential) permits. It also relieves the painful trauma caused by the teeth to the hard palate whenever the pup closes its mouth (and we all know how sharp those baby teeth are!!). More information on interceptive orthodontics can be found later in this book.

In some breeds, a genetic tendency for retained deciduous teeth can also contribute to the development of problems, such as anterior crossbite seen in several of the toy breeds.

It is crucial to remember that genetic malocclusions are not usually seen in all puppies in an affected litter as they are not dominant traits. Puppies can carry the genes contributing to genetic faults without showing any physical signs at all. If an affected puppy is noted, extreme caution should be exerted when planning future breeding from the parents and siblings, and neutering of the affected puppy is strongly recommended.

Although diet often gets the blame for development of malocclusions, the role of nutrition is actually much less significant than is often believed. Obviously gross dietary deficiencies will affect bone and tooth development, for example severe calcium deficiency can lead to ‘rubber jaw’. However, the vast majority of puppies are on balanced, complete diets and have adequate nutrient intake for normal bone and tooth development.

One myth I have heard repeated by several owners is that strict limitation of a puppy’s dietary intake can be used to correct an undershot jaw. This is simply NOT true. Limiting calories will NOT slow the growth of the lower jaw relative to the upper jaw (both jaws receive the same nutrient supply). Such a practice is not only ineffective, it can be detrimental for the puppy’s overall growth and development.

Trauma, infection and other mechanical forces may affect growth and development of the jaws and teeth. Developing tooth buds are highly sensitive to inflammation and infection, and malformed teeth may erupt into abnormal positions (or not erupt at all!). Damage to developing teeth can also occur if the jaw is fractured.

Retained or persistent deciduous (puppy) teeth can also cause malocclusions by forcing the erupting adult teeth into an abnormal position. As previously mentioned, this may be a genetic trait, but can also occur sporadically in any breed of dog.

A full bite assessment can help differentiate between malocclusions which are due to shifting of teeth alone, and those which have an underlying genetic basis. Contact me if you would like to arrange a bite assessment for your puppy

The basic rule is that every dog deserves a pain-free, functional mouth. If there is damage occurring to teeth, or oral tissues, we need to alleviate this, to allow the dog to live happily and healthily. If there is no functional problem and no trauma occurring, then treatment is simply not required.

Sometimes the hardest part is determining whether the problem is in fact causing pain. As we know, dogs are very adept at masking signs of oral pain, and will and will continue to eat despite real pain. Puppies, in particular, don’t know any better if they have had pain since their teeth first erupted very early in life.

Early assessment to determine whether intervention is required is critical in puppies with any signs of occlusal problems. Not only does this allow us to relieve their pain promptly, it can allow for easier correction of problems than if we wait until the permanent teeth have fully erupted and settled into place.

The overriding aim is always to give the dog a healthy, pain-free and functional mouth. Sometimes this will result in a ‘normal’ mouth, whereas in other cases, this might not be realistically achievable.

While some basic advantages and disadvantages of the different treatment options are outlined here, it is very important to seek specific advice for your individual dog, as no two mouths are exactly the same, and an individual bite assessment will help us determine the best course of action together. You can contact us anytime.

Malpositioned teeth may be moved into a more appropriate position using orthodontic appliances such as braces (yes, braces), wires, elastic (masel) chains or plates (similar to those used in humans!). In some cases, this may be a multi-step procedure which means repeated general anaesthetics.

Extraction of lower canine teeth – the roots of these teeth make up about 70% of the front of the jaw, and so there is a potential risk of jaw fracture associated with their removal. Some dogs also use these teeth to keep the tongue in position, so the tongue may hang out after extraction.

Extraction of teeth may severely limit an animal’s success in the show ring, especially in breeds where the correct number of teeth is emphasised in the breed standard.

Orthodontic movement of teeth is a complicated science, and, while some procedures appear quite straightforward, permanent damage to teeth and the surrounding structures can result from inappropriate procedures, poorly fitted appliances, or excessive pressures.

The outdated practice of using rubber bands to move the teeth is not recommended, as they slip down between the tooth and the gum, causing damage to the sensitive tissue here. The forces applied are also difficult to regulate, which can cause damage to the ligaments around the teeth, as well as the tooth roots. Much safer and more effective methods are now available.

Procedures to alter the shape of the teeth and make them fit better in the mouth can also be performed. This may vary from removal of small amounts of enamel (odontoplasty) to create space between teeth, right through to shortening the crown of a tooth to prevent it from causing trauma (crown reduction).

Crown reduction is commonly performed to treat base narrow canines, or class II malocclusions, where the lower canines are puncturing the hard palate. Part of the tooth is surgically amputated, a dressing inside the tooth to promote healing and the tooth is sealed with a white filling (just like the ones human dentists use). This procedure MUST be performed under controlled conditions as it exposes the highly sensitive pulp tissue. If performed incorrectly, the pulp will become infected and extremely painful for the rest of the dog’s life.

This pup has trauma in the roof of her mouth due to her left lower canine. A crown reduction procedure relieves the trauma while maintaining some functionality and avoiding extraction.

Even the less invasive odontoplasty (enamel shaping) can result in exposure of the sensitive dentine or pulp tissue if taken too far, and must be performed with extreme care to avoid permanent problems. Xrays are recommended prior to surgery so we can measure how far we can go before we get into the ‘danger zone’.

Although sometimes practised, clipping the tips of the teeth of puppies is NOT a humane procedure, and not only causes intense pain (imagine how it would feel if your own tooth was cut in half), but the resulting pulp infection can cause irreversible damage to the adult tooth buds which are developing underneath.

Extraction of teeth is sometimes performed, alone or in combination with other orthodontic treatments. This may be the preferred treatment in cases where:

While the dog may lose some function, this is far preferable to doing nothing (this condemns the dog to a life of pain). Indeed, unless released into the wild, dogs do well even if we need to extract major teeth (canines and carnassials), as they have the humans in their pack to do all the hunting and protecting for them.

This is the term we use when we remove deciduous teeth to alter the development of a malocclusion. The most common form of this is when we relieve dental interlock that is restricting normal jaw development. Such intervention does not make the jaw grow faster, but will allow it to develop to its genetic potential by removing the mechanical obstruction.

Extraction of deciduous lower canines and incisors in a puppy with an overbite releases the dental interlock and gives the lower jaw the time to ‘catch up’ (if genetically possible).

As jaw growth is rapid in the first few months of life, it is critical to have any issues assessed and addressed as soon as they are noticed, to give the most time for any potential corrective growth to occur before the adult teeth erupt and dental interlock potentially redevelops. Ideally treatment is performed from eight weeks of age.

Extraction of deciduous teeth is not necessarily as easy as many people imagine. These teeth are very thin-walled and fragile, with long narrow roots extending deep into the jaw. The developing adult tooth bud is sitting right near the root, and can be easily damaged. High detail intraoral (dental) xrays can help us locate these tooth buds, so we can reduce the risk of permanent trauma to them. Under no circumstances should these teeth be snapped or clipped off as this is not only inhumane, but likely to cause serious infection and ongoing problems below the surface.

Permanent enamel damage on adult teeth following extraction od deciduous teeth. The risk of this can be minimised by use of dental x-rays and extremely good surgical technique.

The aim of any veterinary procedure should always be to improve the welfare of the patient, so the invasiveness of any treatment needs to be weighed up against the likely benefits to the dog. Every animal deserves a functional, comfortable bite, but not necessarily a perfect one. Indeed, some malocclusions (particularly those involving skeletal abnormalities) can be difficult to correct entirely.

In addition to the welfare of the individual dog, both veterinarians and breeders need to consider the overall genetic health of the breed. Both the Australian National Kennel Club and (in New South Wales where our practice is situated) the Veterinary Practitioners’ Board stress that alteration of animals to conceal genetic defects for the purpose of improving their value for showing (and breeding) is not ethical.

For animals with malocclusions, very strong consideration needs to be paid to whether or not breeding from the affected animal is in the interests of improving the breed. If there is a genetic component, then neutering or selective breeding is recommended. As the vast majority of orthodontic abnormalities are not dominant in their inheritance (not all pups carrying the ‘bad’ genes will have visible problems), a ‘small’ issue seen sporadically can easily become widespread within a line.

This not only means many pups will have physical problems requiring correction for their own individual welfare, but breeding the problem out again can be extremely difficult.

The bottom line is that, while all dogs will have multiple treatment options available, and in some cases the occlusion can be corrected to the point of being ‘good for show’, advice should definitely be sought about the likelihood of a genetic component prior to embarking upon this, as the consequences for the breed can be devastating if such animals (or their close relatives) become popular sires or dams.

Sometimes a puppy may be missing one or more teeth. In the absence of trauma (which is usually apparent for other reasons!), there are a couple of things that may be going on.

Sometimes a tooth is congenitally missing, that is it has never developed. While dogs can physically cope well with missing teeth, in some breeds this is considered a serious fault, and will severely affect the chances of the dog being successful in the show ring.

Alternatively, a ‘missing’ tooth may be unerupted below the gumline. This can only be diagnosed using xrays. In some cases, the tooth may be trapped under a thickened layer of gum tissue, and surgery to relieve the obstruction (an operculectomy) may allow the tooth to erupt smoothly into the correct position if performed early enough.

Impacted lower canines trapped under thick gum tissue. They are also in a base narrow position. These teeth were able to erupt when tissue was surgically released (operculectomy).

Sometimes, the tooth will be in a favourable position but caught behind a small rim of jawbone – again early surgical intervention may be successful in relieving this obstruction. If the tooth is in an abnormal position or deformed, it may be unable to erupt even with timely surgery.

Impacted or embedded teeth should be removed if they are unable to erupt with assistance. If left in the jaw, a dentigerous cyst may form around the tooth. These can be very destructive as they expand and destroy the jawbone and surrounding teeth. Occasionally these cysts may also undergo malignant transformation (ie develop into cancer).

Firstly, if there are two teeth in one socket (deciduous and adult), the surrounding gum cannot form a proper seal between these teeth, leaving a leaky pathway for oral bacteria to spread straight down the roots of the teeth into the jawbone. Trapping of plaque, food and debris between the teeth also promotes accelerated periodontal disease. This not only causes discomfort and puts the adult tooth at risk of early loss, but allows infection to enter the bloodstream and affect the rest of the body.

If the deciduous tooth is still firmly in position as the adult tooth is erupting, it forces the adult tooth into an abnormal position which can cause a significant malocclusion. For example, the lower adult canines normally erupt on the inside of the deciduous teeth, so if they are forced to erupt alongside them, a painful base narrow malocclusion can result.

The upper adult canines normally erupt in front of the deciduous ones, so forcing them further forward can result in ‘lance’ canines. Finally, the upper adult incisors usually erupt behind their deciduous versions, so if these are retained a rostral crossbite may develop.

Retained upper baby canines force the adult canines to erupt in a more forward position. This can close the gap where the lower canine usually sits, forcing it into a traumatic position.

Puppies play rough, chew whatever they can get hold of, and have tiny teeth with very thin walls. Therefore fractures will sometimes occur. A common misconception is that broken deciduous teeth can be left until they fall out. Unfortunately this is NOT true. From the puppy’s point of view, broken teeth HURT, just as they do in children. Anyone who has had a bad toothache would agree that even a few weeks is a long time to wait for relief!

Broken teeth also become infected, with bacteria from the mouth gaining free passage through the exposed pulp chamber inside the tooth, deep into the underlying jawbone. This is not only painful, but can lead to irreversible damage to the developing adult tooth bud, which may range from defects in the enamel (discoloured patches on the tooth) through to arrested development and inability to erupt. The infection can also spread through the bloodstream to the rest of the body. Waiting for the teeth to fall out is NOT a good option!

We cannot rely on dogs to tell us when they have oral pain. It is up to us to be vigilant and watch for signs of developing problems. Train your pup to allow handling and examination of the mouth from an early age. We will be posting some videos of oral examination tips shortly, watch out in your email inbox for this. Things can change quickly – check their teeth and bite formation frequently as they grow.

Seek veterinary care as soon as a potential problem is noticed – you can call me on 1300 838 336 or email me anytime on support@sydneypetdentistry.com.au for advice or assistance.

Remember, early recognition and treatment is crucial if we want to keep your dog happy and healthy in and out of the show ring. The sooner we treat dental problems, the higher the chance of getting the best possible results with the least invasive treatment.

Have you ever wondered what the Bite is? Or have you ever been confused with the proper terminology – don’t worry you are not alone. With permission of Elizabeth Hennessy, DMV. We are sharing Elizabeth’s article with intention to share the knowledge and help to understand the Bite.

The standard reply is "Oh, just fine. He/she bites a lot, no problem with that bite." This is our first hurdle, the distinction between "bite", "does bite", "is biting" and so on.

Our standard says nothing about number of teeth. This puts the judges in the precarious position of having to assume what the bite might be with all teeth present, given no time to count.

Think about this. We have made no effort to breed for 42 teeth. Missing teeth do not appear to be a problem for our dogs. Bull Terriers don"t chew their food anyway! Back to bites.

This means the upper incisors lock over the lower incisors. The normal position of thelower canine tooth isin front of the upper canine, behind the lateral, or #3 incisor. The tip or crown shouldCLEAR the upper gum on the outside. Key word - OUTSIDE.

The Bull Terrier standard calls for a scissor or level bite. Level means the upper and lower incisors meet edge to edge. The canines should be as defined above.

An overshot bite is uncommon in Bull Terriers and has been referred to as “pig jaw”. Minor defects are usually the result of retained baby teeth, minor discrepancies in the rate of jaw growth and trauma.

Retained baby teeth can contribute to these conditions. To date I don’t believe we have studied enough Bull Terrier mouths to say that these malocclusions result from a “narrow under-jaw”.

Perhaps. If the canine in question is making a hole in the hard palate, minor problems for the dog could result. I have yet to see these conditions impact the use of the “bite”, so to speak.

Our Bull Terrier standard says the bite should be scissor or level. It does not disqualify “bad” bites. Our judges are faced with a challenge as the degree of “bad” determines the degree of fault. BAD IS A RELATIVE TERM.

I have heard numerous adjectives used to describe bites; good, ok, a “thumbnail off level’’, bad and (my favorite) “shocking”. How are we to select and breed correct bites if we don’t understand them? Do we want to? Do we care? The Bull Terriers don’t.

As long as we continue to select for a head shape that is a concept NOT found in nature among canines, we will continue to have bite “problems”. The dogs will continue to operate with what they have (or don’t, as the case may be).

Think about the boxer, the pug and the bulldog. The result of selectively shortening the muzzle is not much different than eliminating the “stop” (found in the generic canine) and curving the upper portion of the skull in the opposite direction. If we are looking for a wide, strong under-jaw and effectively shorten the skull, WHERE IS IT TO GO?

Orthodontic movement is achieved by creating a force on the targeted tooth or teeth. The direction and magnitude of the force is controlled and can be either sustained or intermittent. Over time, this force helps move the teeth through the jawbone and into the desired location. This movement, which is influenced by the compressive or tensile forces transferred through the periodontal ligament, is accomplished by the actions of osteoclasts and osteoblasts.

The course of orthodontic treatments in dogs is much shorter than in people, generally one to three months. In general, most dogs tolerate properly installed and managed orthodontic appliances well. Only veterinarians who are trained in the principles and practice of orthodontics should perform orthodontic treatments.

Many problems can arise during the course of an orthodontic treatment. These problems often result from technical errors, such as too much force or improper direction of force applied to the tooth or inadequate anchorage of teeth with subsequent movement of teeth that were not intended to be moved. Other problems can arise as a result of management errors, such as failure to keep the orthodontic appliance in the dog"s mouth or failure to maintain good oral hygiene.

Following is a discussion of common orthodontic problems in dogs and their typical treatment. Other types of malocclusion may also warrant treatment, and other forms of management are available.

As a rule of thumb, an erupted permanent tooth and its deciduous predecessor should never exist together. When persistent (retained) deciduous teeth is diagnosed, the persistent deciduous teeth should be extracted immediately. Persistent deciduous teeth can prevent permanent teeth from occupying a correct position in the mouth (Figures 2A & 2B), which can lead to potentially traumatic malocclusions. Food and bacterial deposits can also accumulate between the retained deciduous tooth and its permanent counterpart and cause periodontitis. When extracting persistent deciduous teeth, be careful to avoid root tip fracture and other complications.

Figure 2A. A persistent deciduous mandibular canine tooth (arrow) is occupying the space where the permanent mandibular canine tooth should be. A persistent deciduous maxillary canine tooth is occupying the space where the permanent maxillary canine tooth should be, resulting in crowding and leaving little space for the mandibular canine tooth. 2B. Lingually displaced mandibular canine teeth (arrows) will often migrate into their normal positions if persistent deciduous canine teeth are extracted in a timely fashion.

Extracting deciduous teeth is also warranted in cases of dental interlock. During growth and development in puppies, the mandible and maxilla grow independently. Sometimes during growth spurts, one jaw grows faster than the other, and the deciduous teeth can become interlocked, interfering with the normal growth of the shorter jaw. Extracting the deciduous teeth will not promote jaw growth in a dog that is genetically destined to have malocclusion. But in cases in which the interlock has resulted from a temporary discrepancy in jaw growth, relieving dental interlock by extracting the interfering deciduous teeth may allow the shorter jaw to lengthen to its genetic potential. Careful case selection, client education, and meticulous extraction technique to avoid iatrogenic damage to the developing permanent tooth are the keys to successfully removing persiste

8613371530291

8613371530291