asme safety valve testing requirements made in china

Many processes involve the use of high pressure steam, water or air. Piping systems carrying these fluids must be protected from over-pressures that could cause damage or injury. A pressure relief valve is a device that opens to vent any pressure higher than the relief valve’s operating set point. The water heater in your house, for example, has a pressure relief valve set to open at a pressure that is lower than the burst pressure of the heater tank. That way if pressure inside the tank exceeds the relief valve’s set point pressure, the valve will open and vent the pressure before the tank is damaged – you get a wet floor but you don’t have to replace the heater tank.

Pressure relief valves come in all sizes and pressures and these are critical parts of a high pressure piping system carrying steam in an industrial plants, refineries, power plants, etc. The ASME has established criteria for the size and set point pressures for relief valves operating in industrial systems. Additionally, these valve are tested on a regular basis to insure that they open at the correct pressure and do not impede the flow of fluid as the pressure is vented. The vales are tested at their operating pressures and temperatures, and the opening pressure and pressure drop through the valve as it vents must be measured.

There are testing laboratories that are used to test industrial pressure relief valves by simulating the operating conditions for water, air and steam. One customer of Validyne has a test lab capable of generating up to 10,000 lbs. per hour of steam at 300 psig, air flows to 3500 SCFM at 500 psig and water flow rates of 500 gpm at 300 psig. Pressure relief valves are tested depending on their operating conditions, and the valves are instrumented to verify correct operation at their set point pressure.

The Validyne product used to make relief valve measurements is the DP15 pressure transducers. One transducer is used to measure the pressure upstream of the relief valve, a second DP15 measures the downstream pressure. These transducers are 300 or 500 psi, depending on the test. A third DP15 measures the pressure drop across the relief valve when it is flowing and this transducer is typically 100 In H2O full scale. The DP15s are used because they can be mounted remotely from the control station. A large steam relief valve, for example, is connected to piping with runs of 25 and 30 feet. The DP15 can be mounted at the measurement point and the cable to the demodulator can be up to 50 feet with no compromise in calibration.

The pressure transducers are connected to Validyne CD23 demodulator with digital display. The CD23 features large LED displays that are helpful for the operator to see while opening and closing large control valves during the test. The display can be given directly in PSIG and the CD23 provides an analog output proportional to pressure that can be connected to a LabVIEW computer to record the pressures during the test. Alternatively the pressure sensors can also be connected to the USB2250 DAQ.

The Validyne CD23s and DP15s have given many years of service in this difficult environment and this reliability, plus the ability to interface to a data acquisition system make it a great solution for relief valve testing.

On 16.01.2019, the Chinese market supervisory authority SAMR (State Administration for Market Regulation of the Peoples Republic of China) published that “Pipes for Pressure Lines” and “Pressure Valves” are to be included in the catalogue for goods subject to licensing under the Chinese Manufacturer License (CML in short; similar to AD 2000 and ASME; also know as China SQL – China Safety Quality License).

Pressure relief valves (PRVs) are a critical line of defense for pressure vessel protection in the power industry. Generating facilities worldwide depend upon these devices to sense and quickly relieve overpressure conditions to avoid catastrophic damage during process upsets. To ensure these valves will perform as expected, mechanical engineering regulatory bodies mandate the valves be tested on a routine basis.

Some installations make the option of pulling the valve for servicing and testing very difficult. This is particularly true for large size valves, and in the nuclear power industry where valves may be located inside containment areas, making valve access particularly problematic. Fortunately, there is another approved method of testing relief valves for this situation, and this alternative solution is the subject of this article.

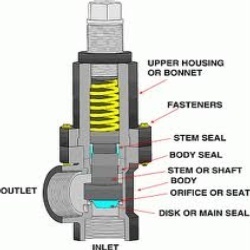

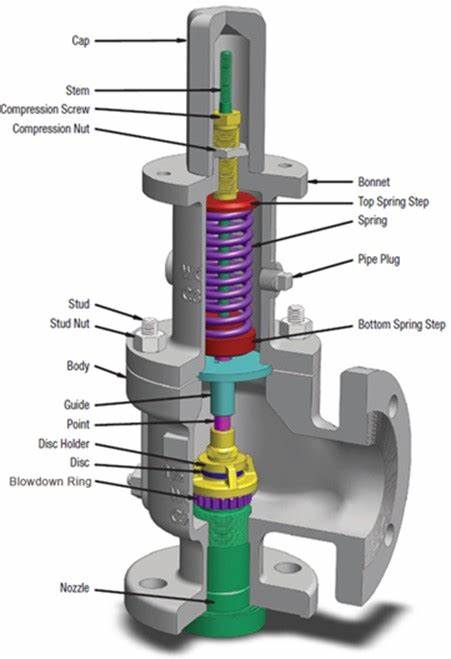

PRVs are relatively, but deceptively, simple devices. They consist of an inlet nozzle attached to the process, which is blocked by a disc held tightly on the nozzle seat (Figure 1). The disc is kept closed by a spring, with adjustments carefully made to dial in the setpoint of the valve.

1. A pressure relief valve (PRV) protects equipment by automatically opening to vent process media when the pressure in the inlet nozzle overcomes the downward force of the spring. Courtesy: Emerson

When the process reaches set pressure, the upward force of the process media offsets the downward force of the spring and the disc lifts off the seat. The process media is relieved through the valve outlet until pressure falls below the setpoint. At this point, the downward force of the spring overcomes the upward force of the process media, and the valve closes.

To ensure the PRV will function when called into action, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) mandates relief valves be functionally checked on a routine basis. Typically, a plant will pull smaller valves from their installed position during process outages, and then inspect and test them in a shop environment to confirm they will function as desired and open at the proper pressure setpoint. However, this method of testing is not so easily achieved in certain cases.

Some relief valves are very large and/or located in difficult to reach areas. Others are welded into place and not easily removed from the process. Valves inside nuclear containment areas are particularly troublesome since access to these areas is usually restricted, with strict adherence to extensive protocols required for entry.

To handle these challenging situations, ASME provides alternate means of testing relief valves, as documented in ASME Performance Test Code (PTC) 25 Pressure Relief Devices. These test methods include in-service testing, which allows the plant to functionally test the relief valve without removing it from the process. This in-situ test method can be quite accurate and effective, but only if it is performed correctly with the right equipment.

Service and testing of PRVs is typically performed during regular maintenance outages as defined by ASME guidelines. Operating pressures and temperatures are brought down to levels conducive for servicing, and the PRVs are tested by maintenance technicians. For this type of in-service, or in-situ testing, lift assist devices are used in conjunction with these lower system pressures to verify the PRV will operate at the setpoint, within allowable tolerances.

ASME-approved, in-service testing allows the use of lift assist devices attached to the spindle of the valve with adapters, along with other test apparatus to perform set pressure verification testing. The equipment shown in Figure 2 allows a carefully monitored lift force to be applied to the spindle of a PRV until the disc lifts off the seat. The process pressure and the lift force are known, enabling this type of a computer-driven system to determine the setpoint of the PRV, and confirm that it falls within tolerance. This specific type of lift assist equipment is known as a set pressure verification device (SPVD).

2. A portable lift assist, or auxiliary lift device, allows a PRV to be functionally tested without removing the valve from the process. Courtesy: Emerson

There are several other types of lift assist devices available to perform in-service set pressure verification testing, with varying degrees of effectiveness. For most applications, an SPVD is the preferred method of in-service testing.

A linear variable differential transformer (LVDT) is used to detect the earliest sign of valve stem movement, in the range of 0.020 inch, well below the point where the valve will go into full lift. At this time, force and pressure values are obtained, and the test is concluded to avoid wasteful discharge of the process media and minimize seat damage.

Perhaps the most important feature of an SPVD is a fully automated test execution system (Figure 3). This system incorporates an industrially hardened portable laptop computer running automated test protocols, including calibration and diagnostics. The computer can print out certified test results and be connected to up to five relief valves, simplifying and speeding test execution.

Some other types of lift devices are more manual and can only be operated by trained personnel, typically provided by the lift device vendor at considerable expense. However, a fully automated SPVD allows most plant technicians to perform PRV set pressure verification tests as needed. The most useful lift assist devices can be installed on a wide variety of PRVs, rather than just on those from specific manufacturers. Ideally, the lift device should be lightweight and easily adaptable to fit a wide range of relief valves.

Cost and scheduling benefits can be realized from self-test execution, and fully automated PRV set pressure testing also helps ensure consistent and accurate test results, regardless of personnel experience. SPVDs typically provide ASME-certified test results with a proven test accuracy of less than +/–1% error, significantly below the typical ASME test accuracy threshold of +/–3%.

SPVD is often the preferred choice to address a number of challenging PRV test issues. Some valves are very large or not easily removed, so an in-service test is clearly the least costly option (Figure 4). This can especially be true for large relief valves that are welded into the process piping.

4. Emerson’s Crosby SPVD is being used to perform an in-service test on this American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) Section III Class 2 safety valve. Installation and testing of the SPVD does not restrict the PRV from operating should process conditions require the valve to open in service. Courtesy: Emerson

Inside nuclear power plants, many large PRVs are located within containment buildings, where access is extremely limited. For critical PRVs in these areas, SPVD lift assist heads and adapters can be permanently installed on the valves, with test cables routed outside the restricted zone and connected to a computer controller.

Since this type of lift device does not impact valve performance during normal operation or overpressure conditions, the PRV can still operate as necessary. Tests can be remotely performed from outside the containment building by simply plugging the cables into a test system and executing the test. Such an installation allows a plant to safely operate under normal conditions and test their critical PRVs on an as-needed basis, while avoiding any potential radiation exposure.

A well-designed lift assist device is a valuable addition to a plant’s PRV maintenance toolset. Every PRV is required to undergo regular in-service testing requirements as defined by the ASME Operation and Maintenance of Nuclear Power Plants code. The code permits use of lift assist devices to perform set pressure verification testing, which is particularly useful in situations where removing the valve from its installed position is not practical. The right lift assist device allows plant personnel to safely execute scheduled maintenance during outage events, or during operation in other cases, ensuring that critical PRVs are functioning per design with correctly adjusted setpoints.

A fully automated SPVD allows plant personnel to perform these tests consistently and accurately, freeing users to schedule and execute PRV tests, without the need for outside vendor involvement. This saves time and cost, and it removes dependence on a single vendor as a service provider. SPVD also provides a means for nuclear power plants to remotely test their critical relief valves, while avoiding exposure in containment areas.

If faced with a PRV testing challenge, plant personnel should consider lift-assist devices, such as an SPVD, as a potential solution. They meet ASME requirements for set pressure verification testing, and the fully automated operation of SPVD guarantees reliable test results, while providing many other benefits noted in this article.

—June DelGrossois the sales director for North America Nuclear and Navy at Emerson for its flow control products. She has worked for a variety of companies, filling roles such as Valve and Instrument Design Engineer, Product Engineering Manager, and Global Product Technical Leader.

**Update to this article, June 7, 2022 : If you found this article helpful, here is a link to another article I recently found that does a nice job explaining the topic: ENGINEERS BEWARE: API vs ASME Relief Valve Orifice Size – Petro Chem Engineering (petrochemengg.com)

NOTE: this article is written to an audience that is familiar with PSVs, PSV sizing, and API and ASME standards at a basic level. I initially wrote this article in early 2017, and due to some great input and questions made significant revisions to increase clarity in mid-2018. I hope it is helpful to you, please send me a message with any comments/questions!

If you"ve ever sized/selected a Pressure Safety-Relief Valve (PSV) using vendor sizing programs or good-old hand calculations, you"ve probably run into a very strange anomaly: Why does a PSV orifice size change between American Petroleum Institute (API) and American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) data sets? What is an "effective" orifice area? How do I know which standard to use when selecting a PSV?

Usually, this issue is one of curiosity and doesn"t affect the end result of what valve is chosen. Common practice is to default to API sizing equations and parameters, and only use ASME data sets for situations outside of the API letter-designations. But what if I told you that approach is likely causing you to oversize about 10% of your PSVs and their respective piping systems?

Most of the time simply using API data sets is fine. And I should note that this is a conservative approach, so you won’t make a mistake doing this. But did you know that PSVs are certified to ASME capacities, not API? And did you know those ASME capacities are nearly always higher than the API ones? I’m guessing you don’t, because there are very few resources available that speak to this topic. I’ve found it common for engineers to understand API 520 quite well, but have a very limited working knowledge of how the ASME BPVC comes into play.

Too often, we leave that third part out of the process, and simply calculate relief loads and select valves using API techniques, without ever checking our selection against certified ASME data. Proper application of these standards is the first key point of this article:

Initial sizing and valve selection is done using API equations, and final valve selection and certification is done using ASME-certified coefficients and capacities.

When sizing a PSV, the sizing equations are always API 520. When a PSV is certified, it is always certified to ASME BPVC (whether one “selects” ASME certification or not!) It"s important to remember that the ASME BPVC is the "code", the standard to which we must design. API 520/526 are "recommended practices" which were developed to give engineers a tool to meet the ASME requirements. Another way to look at it: ASME BPVC sets the goal, API 520/526 provide the instructions, and ASME has the final say.

The BPVC is an enormous code, and not reviewed in detail here. On the subject of PSVs, it basically says that a PSV must be capable of relieving the required load, and it must be tested in a specific manner to be certified to do so. If a valve is tested per the specific directions in the BPVC, it will be ASME certified and receive an ASME UV stamp.

The first thing API does is attempt to standardize physical PSV sizes and design, and it does so in API RP 526, which is targeted at PSV manufacturers. API provides pre-defined valve sizes, with letter designations D through T (API 526). It also defines other details directed toward valve manufacturers (such as temperature ratings). All of this is intended as minimum design standards, and manufacturers are free to exceed these parameters as they wish.

The second thing API does is provide standardized equations and parameters to use when trying to figure out just what size of a PSV one needs for a particular scenario. The equations account for design parameters that ASME doesn"t speak to, such as specific fluid properties, backpressures, critical flow, two-phase flow, and many other aspects of fluid dynamics that will affect the ability of a particular valve to relieve a required load.

API sizing equations are by nature theoretical, standardized, and use default or "dummy" values for several sizing parameters that may or may not reflect the actual values for any specific valve.

API RP 520 very clearly talks about this, and emphasizes that the intended use of its equations is to determine a preliminary valve size, which should be verified with actual data. API intends PSV sizing to be a two-step process, but we are often unaware of this because we (gasp) don’t read the full standard, and/or rely solely on vendor sizing software that hides the iteration from us. See API 520, part 1, section 5.2 for further explanation.

When valves are built, they are built to the API RP 526 standard, however, as one might imagine, when valves are actually tested and certified, the results don’t match up identically to the theoretical values that were calculated. This is where API and ASME intersect; we switch from calculations (API) which were used as a basis to design the valve, to actual empirical data (ASME) to certify the valve. When a valve manufacturer gets the UV code stamp that certifies the valve orifice size and capacity, it is based on actual test results, not API sizing standards. And ASME (which came first) does not have tiered letter designations. The typical D, E, F, etc. sizes we refer to are strictly an API tool, and ASME’s capacity certifications are completely independent of them!

2. They test the final product according to ASME BPVC, and get a result that equates to an effective orifice area of 4.90in2. This is its ASME effective area.

3. A third-party Engineer (you), trying to select a PSV, runs a sizing calculation using API 520 equations on ABC Valve Company"s sizing software, gets a result that requires 4.66in2 to relieve the load, and is now thoroughly confused on what size valve to select.

If one selects the API data set on the sizing software in this example, it will automatically eliminate N-orifice valves as an option, and bump the user up to a P-orifice. However, if one simply selects the ASME data set, the N-orifice valve magically reappears as an option. How can this be? Will the N-orifice work or not?

The short answer is yes, it is certified to an actual area of 4.90in2. So the “N” orifice for this specific PSV will work, and is certified to do so, in this application. Remember: use API to get you close, and ASME to confirm the final answer.

Digest that for a moment. If you’ve sized and purchased more than a dozen PSVs, chances are you have inadvertently selected a PSV a full size larger than you needed to, in a situation much like our example, simply because you chose a PSV based on its API “rating” rather than its real, certified, stamped ASME rating. If that was a small valve, impact was probably nil. But what if this happened on a valve that resulted in selecting a 8x10 PSV when you could have used a 6x8?

If you’re like me, that answer isn’t very satisfying. Why on earth is this so confusing? How can you simply hit a button on the sizing program and a different size of valve is suddenly acceptable? The key lies how the main coefficient of discharge, Kd, is handled, and how capacities are determined.

There are several K values used in API calculations, all of which have generic values defined in API 520 that can be used for preliminary sizing. These are the numbers used in initial sizing calculations to get us close, then (if we do this correctly) replaced with the actual/tested/empirical/ASME values when we get a certified valve. Remember, anytime you hear “certified” or “stamped”, think ASME.

Let’s take the numbers from the example above, which came from an attempt to size a valve for liquid relief. API says to use a value of Kd=0.65 for liquid relief. If one uses the API data set on the vendor software, then the calculation stops here, and you get a required area of 4.66in2. When you select a valve, you’re comparing that to the API effective (actual) area of an N orifice, which is 4.34 in2, which is obviously too small and you’d logically step up to a P orifice. However….

Remember that the API N-orifice area is just the benchmark, a minimum requirement, and may or may not (most likely not) reflect the actual area of a real-life PSV. Once a valve is selected, all of those K values and capacities should be replaced with actual ASME-certified K values, also determined by testing, that are specific to each valve model, and the calculations performed again.

Normally, ASME-certified K-values are smaller than the API dummy values, driving up the required orifice area. So valve manufacturers have to over-design their valves to make up for it, resulting in ASME-certified areas and capacities that typically exceed the benchmark API ones. The end result of all this?

It (almost) all boils down to one sneaky little sentence in the ASME BPVC which mandates a 10% safety factor on the empirically-determined Kd that “de-rates” the valve (see ASME BPVC Section VIII, UG-131.e.2). This tidbit seems to be a little-known fact that is key to proper PSV sizing and selection, because as engineers we often pile safety factors upon each other and oversize our equipment. I cannot highlight this enough:

I mentioned above that ASME K values are nearly always lower than API values, due to this 10% de-rating. The PSV in our example scenario has a determined Kd of 0.73, which is adjusted down by 10% for a final AMSE Kd of 0.66, slightly higher than the dummy API value (that just means that this particular valve proved it could do about 11% better than the minimum theoretical flow calculated by API when it was tested). So, for our valve in question, the Required ASME area is slightly less than the API area. This is atypical, but not unheard of, and again points to the importance of checking the ASME ratings of any valve you select, and comparing against the API benchmarks.

But that’s not the whole picture. For our example, the net effect of the ASME Kd is basically nothing. So how is it the ASME capacity is higher? This brings us to the last key concept:

When you choose to use the ASME data on a specific valve, it’s not just the Kd sizing factor that changes; the actual orifice area and therefore the capacity of the valve also adjusts to empirical, certified values. You can generally expect both values to increase over the API values.

Why is this? Simply that any given real-world valve is usually over-designed so that it will meet and exceed the required minimum capacity of its corresponding API size. What a simple concept, but so often overlooked by engineers!

Back to our example scenario: even though the ASME Kd, and hence required area, adjustment had a negligible effect, the actual ASME orifice area, and hence capacity, is significantly higher than the listed API area and capacity for an N-orifice. Below is a summary:API N Orifice: 4.340 in2

*Note: this is data from a real case; the specific PSV make/model is omitted. Did you catch the result? The actual, certified capacity of this valve is nearly 13% higher than the generic N-orifice valve, and that includes its 10% safety factor!

With this adjusted orifice area, we can compare to the ASME certified area (which is always going to be larger than the API area), and we have our final answer for the valve size. Often this will not result in a different choice of valve, but sometimes, as in the example case, it will allow us to use a valve with an API letter designation that did not appear large enough based on its API effective area. This can save time and money for our plants by preventing over-sizing valves, leading to smaller piping systems to support them. And remember, the ASME values are empirical and have a 10% safety factor built in, so we don’t need to worry about cutting the design too close; the conservatism is already built in to the method. We can choose the Brand X N-orifice valve and sleep well at night!

Avoid simply defaulting to the API data set for the final “rating” or data sheet when selecting a PSV. Use API sizing calculations as they are intended: for preliminary valve selection. Then switch to the ASME data set. This will often (but not always, remember, it"s valve-specific) result in two differences:

2. A required orifice area that is greater than the one calculated by API. This is also ok, and is usually due to the 10% de-rating on Kd that ASME requires.

There are various safety valves available to meet various applications and performance criteria demanded by various industries. Furthermore, national standards determine many types of varied safety valves.

Standard ASME I and ASME VIII standards for boiler applications and vessels and ASME / ANSI PTC 25.3 standards for safety valves and relief valves provide the following definition. These standards set performance characteristics and define various types of safety valves used:

ASME I valve - A safety relief valve conforming to the requirements of Section I of the ASME pressure vessel code for boiler applications which will open within 3% overpressure and close within 4%. It will usually feature two blowdown rings and is identified by a National Board ‘V’ stamp.

ASME VIII valve - A safety relief valve conforming to the requirements of Section VIII of the ASME pressure vessel code for pressure vessel applications which will open within 10% overpressure and close within 7%. Identified by a National Board ‘UV’ stamp.

Full bore safety valve - A safety valve having no protrusions in the bore, and wherein the valve lifts to an extent sufficient for the minimum area at any section, at or below the seat, to become the controlling orifice.

Conventional safety relief valve - The spring housing is vented to the discharge side, hence operational characteristics are directly affected by changes in the backpressure to the valve.

Balanced safety relief valve - A balanced valve incorporates a means of minimizing the effect of backpressure on the operational characteristics of the valve.

Pilot operated pressure relief valve - The major relieving device is combined with, and is controlled by, a self-actuated auxiliary pressure relief device.

Power-actuated safety relief valve - A pressure relief valve in which the major pressure-relieving device is combined with, and controlled by, a device requiring an external source of energy.

Standard safety valve - A valve which, following the opening, reaches the degree of lift necessary for the mass flowrate to be discharged within a pressure rise of not more than 10%. (The valve is characterized by a pop-type action and is sometimes known as high lift).

Full lift (Vollhub) safety valve - A safety valve which, after commencement of lift, opens rapidly within a 5% pressure rise up to the full lift as limited by the design. The amount of lift up to the rapid opening (proportional range) shall not be more than 20%.

Directly loaded safety valve - A safety valve in which the opening force underneath the valve disc is opposed by a closing force such as a spring or a weight.

Proportional safety valve - A safety valve that opens more or less steadily in relation to the increase in pressure. Sudden opening within a 10% lift range will not occur without a pressure increase. Following opening within a pressure of not more than 10%, these safety valves achieve the lift necessary for the mass flow to be discharged.

Diaphragm safety valve - A directly loaded safety valve wherein linear moving and rotating elements and springs are protected against the effects of the fluid by a diaphragm

Bellows safety valve - A directly loaded safety valve wherein sliding and (partially or fully) rotating elements and springs are protected against the effects of the fluids by a bellows. The bellows may be of such a design that it compensates for influences of backpressure.

Controlled safety valve- Consists of the main valve and a control device. It also includes direct acting safety valves with supplementary loading in which, until the set pressure is reached, an additional force increases the closing force.

Safety valve - A safety valve which automatically, without the assistance of any energy other than that of the fluid concerned, discharges a quantity of the fluid so as to prevent a predetermined safe pressure from being exceeded, and which is designed to re-close and prevent further flow of fluid after normal pressure conditions of service have been restored. Note; the valve can be characterized either by pop action (rapid opening) or by opening in proportion (not necessarily linear) to the increase in pressure over the set pressure.

Directly loaded safety valve - A safety valve in which the loading due to the fluid pressure underneath the valve disc is opposed only by a direct mechanical loading device such as weight, lever, and weight, or a spring.

Assisted safety valve - A safety valve which by means of a powered assistance mechanism, may additionally be lifted at a pressure lower than the set pressure and will, even in the event of a failure of the assistance mechanism, comply with all the requirements for safety valves given in the standard.

Supplementary loaded safety valve - A safety valve that has, until the pressure at the inlet to the safety valve reaches the set pressure, an additional force, which increases the sealing force.

Notes; This additional strength (additional burden), which can be provided through foreign resources, is reliably released when the pressure on the safety valve inlet reaches the specified pressure. The amount of additional loading is very regulated that if the additional loading is not released, the safety valve will reach its certified discharge capacity at a pressure which is no greater than 1.1 times the maximum pressure that is permitted to be protected.

Pilot operated safety valve - A safety valve, the operation of which is initiated and controlled by the fluid discharged from a pilot valve, which is itself, a directly loaded safety valve subject to the requirement of the standard.

The common characteristic shared between the definitions of conventional safety valves in the different standards, is that their operational characteristics are affected by any backpressure in the discharge system. It is important to note that the total backpressure is generated from two components; superimposed backpressure and the built-up backpressure:

Subsequently, in a conventional safety valve, only the superimposed backpressure will affect the opening characteristic and set value, but the combined backpressure will alter the blowdown characteristic and re-seat value.

Once the valve starts to open, the effects of built-up backpressure also have to be taken into account. For a conventional safety valve with the spring housing vented to the discharge side of the valve.

Therefore, if the back pressure is greater than the overpressure, the valve will tend to close, reducing the flow. This can lead to instability within the system and can result in flutter or chatter of the valve.

In general, if conventional safety valves are used in applications, where there is excessive built-up backpressure, they will not perform as expected. According to the API 520 Recommended Practice Guidelines:

A conventional pressure relief valve should typically not be used when the built-up backpressure is greater than 10% of the set pressure at 10% overpressure. A higher maximum allowable built-up backpressure may be used for overpressure greater than 10%.

The European Standard EN ISO 4126, however, states that the built-up backpressure should be limited to 10% of the set pressure when the valve is discharging at the certified capacity.

For the majority of steam applications, the back pressure can be maintained within these limits by carefully sizing any discharge pipes. This will be discussed in Module 9.4. If, however, it is not feasible to reduce the backpressure, then it may be necessary to use a balanced safety valve.

Balanced safety valves are those that incorporate a means of eliminating the effects of backpressure. There are two basic designs that can be used to achieve this:

The bellows arrangement prevents back pressure acting on the upper side of the disc within the area of the bellows. The disc area extending beyond the bellows and the opposing disc area are equal, and so the forces acting on the disc are balanced, and the backpressure has little effect on the valve opening pressure.

Bellows failure is an important concern when using a bellows balanced safety valve, as this may affect the set pressure and capacity of the valve. It is important, therefore, that there is some mechanism for detecting any uncharacteristic fluid flow through the bellows vents. In addition, some bellows balanced safety valves include an auxiliary piston that is used to overcome the effects of backpressure in the case of bellows failure. This type of safety valve is usually only used on critical applications in the oil and petrochemical industries.

Since balanced pressure relief valves are typically more expensive than their unbalanced counterparts, they are commonly only used where high-pressure manifolds are unavoidable, or in critical applications where a very precise set pressure or blowdown is required.

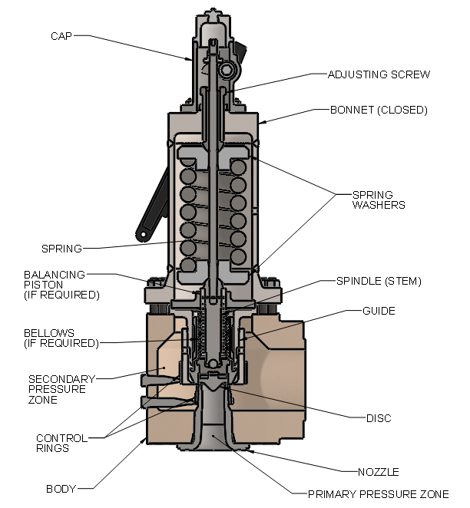

This type of safety valve uses the flowing medium itself, through a pilot valve, to apply the closing force on the safety valve disc. The pilot valve is itself a small safety valve.

The diaphragm type is typically only available for low-pressure applications and it produces a proportional type action, characteristic of relief valves used in liquid systems. They are therefore of little use in steam systems, consequently, they will not be considered in this text.

The piston-type valve consists of the main valve, which uses a piston-shaped closing device (or obturator), and an external pilot valve. Below photo shows a diagram of a typical piston type, pilot-operated safety valve.

The piston and seating arrangement incorporated in the main valve is designed so that the bottom area of the piston, exposed to the inlet fluid, is less than the area of the top of the piston. As both ends of the piston are exposed to the fluid at the same pressure, this means that under normal system operating conditions, the closing force, resulting from the larger top area, is greater than the inlet force. The resultant downward force therefore holds the piston firmly on its seat.

If the inlet pressure were to rise, the net closing force on the piston also increases, ensuring that a tight shut-off is continually maintained. However, when the inlet pressure reaches the set pressure, the pilot valve will pop open to release the fluid pressure above the piston. With much less fluid pressure acting on the upper surface of the piston, the inlet pressure generates a net upwards force and the piston will leave its seat. This causes the main valve to pop open, allowing the process fluid to be discharged.

When the inlet pressure has been sufficiently reduced, the pilot valve will reclose, preventing the further release of fluid from the top of the piston, thereby re-establishing the net downward force, and causing the piston to reseat.

Pilot operated safety valves offer good overpressure and blowdown performance (a blowdown of 2% is attainable). For this reason, they are used where a narrow margin is required between the set pressure and the system operating pressure. Pilot operated valves are also available in much larger sizes, making them the preferred type of safety valve for larger capacities.

One of the main concerns with pilot operated safety valves is that the small bore, pilot connecting pipes are susceptible to blockage by foreign matter, or due to the collection of condensate in these pipes. This can lead to the failure of the valve, either in the open or closed position, depending on where the blockage occurs.

The terms full lift, high lift and low lift refer to the amount of travel the disc undergoes as it moves from its closed position to the position required to produce the certified discharge capacity, and how this affects the discharge capacity of the valve.

A full lift safety valve is one in which the disc lifts sufficiently, so that the curtain area no longer influences the discharge area. The discharge area, and therefore the capacity of the valve are subsequently determined by the bore area. This occurs when the disc lifts a distance of at least a quarter of the bore diameter. A full lift conventional safety valve is often the best choice for general steam applications.

The disc of a high lift safety valve lifts a distance of at least 1/12th of the bore diameter. This means that the curtain area, and ultimately the position of the disc, determines the discharge area. The discharge capacities of high lift valves tend to be significantly lower than those of full lift valves, and for a given discharge capacity, it is usually possible to select a full lift valve that has a nominal size several times smaller than a corresponding high lift valve, which usually incurs cost advantages.Furthermore, high lift valves tend to be used on compressible fluids where their action is more proportional.

In low lift valves, the disc only lifts a distance of 1/24th of the bore diameter. The discharge area is determined entirely by the position of the disc, and since the disc only lifts a small amount, the capacities tend to be much lower than those of full or high lift valves.

Except when safety valves are discharging, the only parts that are wetted by the process fluid are the inlet tract (nozzle) and the disc. Since safety valves operate infrequently under normal conditions, all other components can be manufactured from standard materials for most applications. There are however several exceptions, in which case, special materials have to be used, these include:

Cast steel - Commonly used on higher pressure valves (up to 40 bar g). Process type valves are usually made from a cast steel body with an austenitic full nozzle type construction.

For all safety valves, it is important that moving parts, particularly the spindle and guides are made from materials that will not easily degrade or corrode. As seats and discs are constantly in contact with the process fluid, they must be able to resist the effects of erosion and corrosion.

The spring is a critical element of the safety valve and must provide reliable performance within the required parameters. Standard safety valves will typically use carbon steel for moderate temperatures. Tungsten steel is used for higher temperature, non-corrosive applications, and stainless steel is used for corrosive or clean steam duty. For sour gas and high temperature applications, often special materials such as monel, hastelloy and ‘inconel’ are used.

Standard safety valves are generally fitted with an easing lever, which enables the valve to be lifted manually in order to ensure that it is operational at pressures in excess of 75% of set pressure. This is usually done as part of routine safety checks, or during maintenance to prevent seizing. The fitting of a lever is usually a requirement of national standards and insurance companies for steam and hot water applications. For example, the ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code states that pressure relief valves must be fitted with a lever if they are to be used on air, water over 60°C, and steam.

A test gag (Figure 9.2.7) may be used to prevent the valve from opening at the set pressure during hydraulic testing when commissioning a system. Once tested, the gag screw is removed and replaced with a short blanking plug before the valve is placed in service.

The amount of fluid depends on the particular design of the safety valve. If the emission of this fluid into the atmosphere is acceptable, the spring housing may be vented to the atmosphere – an open bonnet. This is usually advantageous when the safety valve is used on high-temperature fluids or for boiler applications as, otherwise, high temperatures can relax the spring, altering the set pressure of the valve. However, using an open bonnet exposes the valve spring and internals to environmental conditions, which can lead to damage and corrosion of the spring.

When the fluid must be completely contained by the safety valve (and the discharge system), it is necessary to use a closed bonnet, which is not vented to the atmosphere. This type of spring enclosure is almost universally used for small screwed valves and, it is becoming increasingly common on many valve ranges since, particularly on steam, discharge of the fluid could be hazardous to personnel.

Some safety valves, most commonly those used for water applications, incorporate a flexible diaphragm or bellows to isolate the safety valve spring and upper chamber from the process fluid, (see Figure 9.2.9).

As soon as mankind was able to boil water to create steam, the necessity of the safety device became evident. As long as 2000 years ago, the Chinese were using cauldrons with hinged lids to allow (relatively) safer production of steam. At the beginning of the 14th century, chemists used conical plugs and later, compressed springs to act as safety devices on pressurised vessels.

Early in the 19th century, boiler explosions on ships and locomotives frequently resulted from faulty safety devices, which led to the development of the first safety relief valves.

In 1848, Charles Retchie invented the accumulation chamber, which increases the compression surface within the safety valve allowing it to open rapidly within a narrow overpressure margin.

Today, most steam users are compelled by local health and safety regulations to ensure that their plant and processes incorporate safety devices and precautions, which ensure that dangerous conditions are prevented.

The principle type of device used to prevent overpressure in plant is the safety or safety relief valve. The safety valve operates by releasing a volume of fluid from within the plant when a predetermined maximum pressure is reached, thereby reducing the excess pressure in a safe manner. As the safety valve may be the only remaining device to prevent catastrophic failure under overpressure conditions, it is important that any such device is capable of operating at all times and under all possible conditions.

Safety valves should be installed wherever the maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP) of a system or pressure-containing vessel is likely to be exceeded. In steam systems, safety valves are typically used for boiler overpressure protection and other applications such as downstream of pressure reducing controls. Although their primary role is for safety, safety valves are also used in process operations to prevent product damage due to excess pressure. Pressure excess can be generated in a number of different situations, including:

The terms ‘safety valve’ and ‘safety relief valve’ are generic terms to describe many varieties of pressure relief devices that are designed to prevent excessive internal fluid pressure build-up. A wide range of different valves is available for many different applications and performance criteria.

In most national standards, specific definitions are given for the terms associated with safety and safety relief valves. There are several notable differences between the terminology used in the USA and Europe. One of the most important differences is that a valve referred to as a ‘safety valve’ in Europe is referred to as a ‘safety relief valve’ or ‘pressure relief valve’ in the USA. In addition, the term ‘safety valve’ in the USA generally refers specifically to the full-lift type of safety valve used in Europe.

Pressure relief valve- A spring-loaded pressure relief valve which is designed to open to relieve excess pressure and to reclose and prevent the further flow of fluid after normal conditions have been restored. It is characterised by a rapid-opening ‘pop’ action or by opening in a manner generally proportional to the increase in pressure over the opening pressure. It may be used for either compressible or incompressible fluids, depending on design, adjustment, or application.

Safety valves are primarily used with compressible gases and in particular for steam and air services. However, they can also be used for process type applications where they may be needed to protect the plant or to prevent spoilage of the product being processed.

Relief valve - A pressure relief device actuated by inlet static pressure having a gradual lift generally proportional to the increase in pressure over opening pressure.

Relief valves are commonly used in liquid systems, especially for lower capacities and thermal expansion duty. They can also be used on pumped systems as pressure overspill devices.

Safety relief valve - A pressure relief valve characterised by rapid opening or pop action, or by opening in proportion to the increase in pressure over the opening pressure, depending on the application, and which may be used either for liquid or compressible fluid.

In general, the safety relief valve will perform as a safety valve when used in a compressible gas system, but it will open in proportion to the overpressure when used in liquid systems, as would a relief valve.

Safety valve- A valve which automatically, without the assistance of any energy other than that of the fluid concerned, discharges a quantity of the fluid so as to prevent a predetermined safe pressure being exceeded, and which is designed to re-close and prevent further flow of fluid after normal pressure conditions of service have been restored.

8613371530291

8613371530291