first step act safety valve price

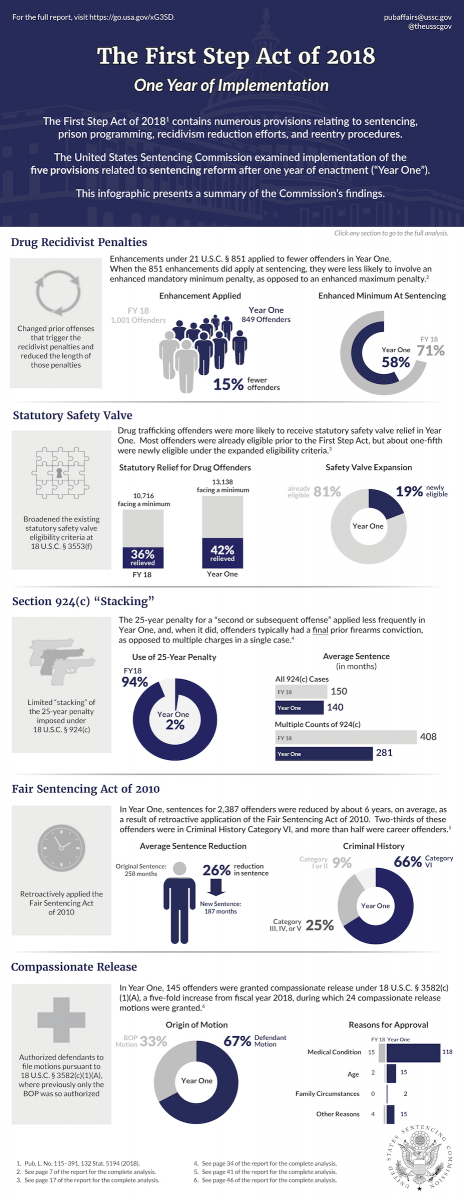

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

For reference, these refer to the statutory language of 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A) and 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B), which instruct the federal judge on how he or she shall sentence anyone convicted of the manufacture, distribution, or dispensing of a controlled substance (i.e., an illegal drug) or possession with intent to either of these things.

How do you know if you are charged with one of these federal drug crimes that come with a mandatory minimum sentence of either 5-to-40 years (a “b1B” case) or 10-to-life (a “b1A” case)? Read the language of your Indictment. It will specify the statute’s citation. If you do not have a copy of your Indictment, please feel free to contact my office and we can provide you a copy.

Can’t there be any way to get around that set-in-stone bottom line? Yes. There is also a statutory exception which allows the federal judge to dip below that mandatory minimum number of years in some situations. It is called the “Safety Valve” defense.

The law, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), provides for an exception that allows the federal judge some leeway in drug crime convictions where he or she would otherwise be required to follow the mandatory minimum sentencing statute. This is the Safety Value statute. It states as follows:

(f)Limitation on Applicability of Statutory Minimums in Certain Cases.—Notwithstanding anyother provision of law, in the case of an offense under section 401, 404, or 406 of theControlled Substances Act(21 U.S.C. 841, 844, 846), section 1010 or 1013 of theControlled Substances Import and Export Act(21 U.S.C. 960, 963), or section 70503 or 70506 of title 46, the court shall impose a sentence pursuant to guidelines promulgated by the United States Sentencing Commission undersection 994 of title 28without regard to any statutory minimum sentence, if the court finds at sentencing, after the Government has been afforded the opportunity to make a recommendation, that—

(4)the defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor of others in the offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in section 408 of theControlled Substances Act; and

(5)not later than the time of the sentencing hearing, the defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

The only way to allow for this exception to be applied in a federal sentencing hearing is for the defense to argue its application and to provide authenticated and admissible support for use of the Safety Valve.

How does the defense do this? It takes much more than referencing the exception to the general rule itself. The defense will have to demonstrate the convicted defendant meets the Safety Valve’s five (5) requirements.

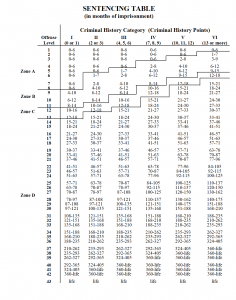

For a successful safety valve defense, the defense has to show that the total Criminal History Points are four (4) or less. If you have a maximum of four Criminal History points, you have met the first criteria for the safety valve.

Note: prior to the passage of the First Step Act, things were much harsher. If the defense had even two Criminal History Points, then the accused was ineligible for the safety valve. The First Step Act increased the number of points, or score, from one to four as the maximum allowed for application of the safety valve. For more on the First Step Act, see The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 1 of 2 and The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 2 of 2.

Looking at the Safety Valve statute ( 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)), the second step in achieving application of the safety valve defense involves the circumstances of the underlying criminal activity and whether or not it involved violence of threats or violence, or if the defendant possessed a firearm at the time.

It has been my experience that it is pretty common for there to be a firearm of some sort involved in a federal drug crime prosecution. Here, the impact of Texas being a part of the Fifth Judicial District for the United States Court of Appeals (“Fifth Circuit”) is important.

In the USSG, two points are given (“enhanced”) for possessing a firearm in furtherance of a federal drug trafficking offense. See, USSG §2D1.10, entitled Endangering Human Life While Illegally Manufacturing a Controlled Substance; Attempt or Conspiracy.

Meanwhile, the Fifth Circuit has ruled that under the Safety Valve Statute, the standard for the government is much higher. According to their ruling, in order to be disqualified from application of the safety valve because of possession of a firearm, the defendant has to have been actually in possession of the firearm or in construction possession of it. See, US v. Wilson, 105 F.3d 219 (5th Cir. 1997).

This is the example of the importance of effective criminal defense representation, where research reveals that it is easier to achieve a safety valve defense with a reference to case law. The Fifth Circuit allows a situation where someone can get two (2) points under the USSG (“enhancement”) and still be eligible for the safety valve defense.

The commentary to § 5C1.2(2) provides that “[c]onsistent with [U.S.S.G.] § 1B1.3 (Relevant Conduct),” the use of the term “defendant” in § 5C1.2(2) “limits the accountability of the defendant to his own conduct and conduct that he aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused.” See U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, comment. (n.4). This language mirrors § 1B1.3(a)(1)(A). Of import is the fact that this language omits the text of § 1B1.3(a)(1)(B) which provides that “relevant conduct” encompasses acts and omissions undertaken in a “jointly undertaken criminal activity,” e.g. a conspiracy.

Being bound by this commentary, we conclude that in determining a defendant’s eligibility for the safety valve, § 5C1.2(2) allows for consideration of only the defendant’s conduct, not the conduct of his co-conspirators. As it was Wilson’s co-conspirator, and not Wilson himself, who possessed the gun in the conspiracy,the district court erred in concluding that Wilson was ineligible to receive the benefit of § 5C1.2. Because application of § 5C1.2 is mandatory, see U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2 (providing that the court “shall” impose a sentencing without regard to the statutory minimum sentence if the defendant satisfies the provision’s criteria), we vacate Wilson’s sentence and remand for resentencing.

The defense must also be able to prove that the defendant’s role in the underlying criminal offense did not result in the death or bodily injury of someone else to achieve the safety valve defense under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In drug cases, this can mean more than some type of violent scenario. The mere type of drug or controlled substance involved can impact the success of this defense. Sometimes, the drugs themselves are the type that can cause severe harm or death. Several controlled substances can be lethal. In a federal drug case, there is a special definition for death resulting from the distribution of a controlled substance.

If the defense can prove with authenticated and admissible evidence that the defendant did not distribute a drug or controlled substance that ended up with someone’s death, or severe bodily injury, then the safety valve defense will be available to them.

Role adjustments happen when someone is alleged to be involved in a conspiracy, and they act in some type of position of responsibility. They can be a leader, or organizer, or somebody who supervises other people in the operations, all as defined in the USSG.

If you are to achieve the safety valve defense, you cannot receive any “role adjustment” under the Sentencing Guidelines. This must be established to the court by your defense attorney at the sentencing.

The defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

I realize that for many people, this language brings with it the assumption that the defendant has to be a snitch in order to meet this requirement for the safety valve defense. This is not true.

With an experienced criminal defense lawyer, what it does mean is that the defendant has a meeting with the authorities with the goal of meeting the Safety Valve Statute requirements and no more.

The attorney can limit the scope of the meeting. He or she can make sure that law enforcement follows the rules for the meeting. The meeting is necessary for the defendant to achieve a safety valve defense, so there is no way to avoid a safety valve interview.

I arranged for my client to have his safety valve meeting as well as establishing the other criteria needed for application of the Safety Valve statute. I was present at the meeting. There was no cooperation regarding the other defendants, and he did nothing more than the minimum to qualify for the defense. He was no snitch.

As a result, the safety valve was applied by the federal judge and my client achieved a safety valve application where he was sentenced to 8 years for distribution of meth: well below the 10 years of the mandatory minimums and the USSG calculation in his case of around 14 years.

Sadly, the same day that my client was sentenced, so were several of the co-conspirator defendants. I was aware that they were also eligible for the safety valve defense. However, the federal agent at the sentencing hearings that day told me that their lawyers never contact the government for a safety valve meeting.

They were never debriefed, so they could not meet the requirements for application of the safety value statute. The judge had no choice –they each had to be sentenced to the mandatory minimum sentences under the law.

More than a year after it was enacted in 2018, key parts of the law are working as promised, restoring a modicum of fairness to federal sentencing and helping to reduce the country’s unconscionably large federal prison population. But other parts are not, demonstrating the need for continued advocacy and more congressional oversight. The way the Justice Department has been handling prisoner releases during the coronavirus pandemic gives some insight into what’s going wrong.

President Trump has bragged about signing the law, which was the first criminal justice reform bill passed in nearly a decade. But simply signing it is not enough. He needs to see it through.

The First Step Act is the product of years of advocacy by people across the political spectrum. Indeed, a very similar bipartisan bill nearly passed in 2015, but was dragged down by election-year politics. The Trump administration began working on its own criminal justice bill in early 2018, and an initial deal was catalyzed by a core group of bipartisan legislators. It was then refined through a series of compromises and, once the Senate decided to pick up the bill, sailed through both houses of Congress with supermajority support.

The law we now know as the First Step Act accomplishes two discrete things, both aimed at making the federal justice system fairer and more focused on rehabilitation.

Its sentencing reformcomponents shorten federal prison sentences and give people additional chances to avoid mandatory minimum penalties by expanding a “safety valve” that allows a judge to impose a sentence lower than the statutory minimum in some cases. These parts of the First Step Act are almost automatic: once the act was signed, judges immediately began sentencing people to shorter prison terms in cases came before them. Similarly, people in federal prison for pre-2010 crack cocaine offenses immediately became eligible to apply for resentencing to a shorter prison term.

The law’s prison reformelements are designed to improve conditions in federal prison in two ways. One is by curbing inhumane practices, such as eliminating the use of restraints on pregnant women and encouraging placing people in prisons that are closer to their families. The other is by reorienting prisons around rehabilitation rather than punishment. That is no small task. Successfully expanding rehabilitative programming in federal prison will require significant follow-through from Congress and the Department of Justice. It’s no surprise, then, that these distinct parts of the act are functioning differently.

Before 2010, an offense involving 5 grams of crack cocaine, a form of the drug more common in the Black community, was punished as severely as one involving 500grams of powder. The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 changed that, reducing this 100:1 disparity to 18:1 — but only on a forward-going basis. People convicted under the now-outdated crack laws were stuck serving the very sentences that Congress had just repudiated.

The First Step Act fixed that by making the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive. According to the Justice Department, as of May, roughly 3,000 people serving outdated sentences for crack cocaine crimes had already been resentenced to shorter prison terms. Shortened or bypassed mandatory minimums mean that every year another estimated 2,000 people will receive prison sentences 20 percent shorter than they would have.

Another 3,100 people were released in July 2019, anywhere from a few days to a few months early, when the First Step Act’s “good time credit fix” went into effect. This simple change allowed people in federal prison to earn approximately an extra week off their sentence per year — and it applied retroactively, too. For some people it meant seeing their friends and family months earlier than expected.

Taken together, these changes represent an important decrease in incarceration. One year after the First Step Act was signed, the federal prison population was around 5,000 people smaller, continuing several years of declines. It has continued to shrink amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

To be sure, there’s still a long way to go: the federal prison population remains sky-high. And the Department of Justice does not appear to be in complete lockstep with the White House’s celebration of the law. In some old crack cocaine cases, federal prosecutors are opposing resentencing motions or seeking to reincarcerate people who have just been released. Prosecutors in these cases argue that any motions for resentencing must also consider the (often higher) amount of the drug the applicant possessed according to presentence reports. Other technical disputes are also cropping up, with the Department of Justice often arguing for a narrow interpretation of the First Step Act.

The First Step Act calls for the Bureau of Prisons to significantly expand these opportunities. Within a few years, the BOP must have “evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities” available for allpeople in prison. That means vocational training, educational classes, and behavioral therapy (to name a few options recommended in the act) should be staffed and broadly available. Participating in these programs will in turn enable imprisoned people to earn “time credits” that they can put toward a transfer to prerelease custody — that is, a halfway house or even home confinement — theoretically allowing them to finish their sentence outside of a prison.

Rolling out this system as intended will be a challenge, however, in part because BOP programs are already understaffed and underfunded. Around 25 percent of people spending more than a year in federal prison have completed zeroprograms. A recent BOP budget document described a lengthy waiting list for basic literacy programs. And according to the Federal Defenders of New York, the true extent of the BOP’s programming shortfall isn’t even known, because the BOP won’t share information on programming availability or capacity. The bureau offered little insight into its existing capacity and needs at a pair of congressional oversight hearings last fall. Worse, a recent report from the First Step Act’s Independent Review Committee, made up of outside experts to advise and assist the government with implementing the law, casts doubt on the quality of the BOP’s existing programming.

The BOP’s lack of transparency also makes it hard to know how “time credits” are being awarded — and thus, whether the BOP is permitting people to make progress toward prerelease custody as Congress intended. The First Step Act provides that most imprisoned people may earn 10 to 15 days of “time credits” for every 30 days of “successful participation” in recidivism-reduction programming. But a recent report suggests the BOP will award a specific number of “hours” for each program. How many “hours” make up a “day,” for the purpose of awarding credits? This highly technical issue may appear trivial, but could significantly affect the reach of the First Step Act.

People with inside knowledge of the system point to other concerns, too. The law excludes some imprisoned people from earning credits based on the crime that led to their incarceration or their role in the offense, and some advocates report that the BOP has applied those exclusions broadly, disqualifying a much larger part of the imprisoned population than Congress intended. Advocates also have heard that program availability in prisons is much spottier than the BOP has suggested, rendering illusory the DOJ’s claim that people are already being assigned to programs and “productive activities” tailored to their needs.

Any expansion of programming also won’t be free. Knowing that, the First Step Act authorized $75 million per year for five years for implementation. But authorization is only the beginning of the budgeting process. Congress must also formally appropriate money to the BOP to fund the First Step Act for each year that it is authorized.

Thankfully, in December 2019, Congress passed and the president signed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, which included full funding for the First Step Act through the end of the current fiscal year. That makes up for a bumpy start: last year, Congress failed to appropriate anything at all, forcing the DOJ to use $75 million from elsewhere in its budget to cover the temporary shortfall.

While this new funding is good news, it still might not be enough. According to a member of the Independent Review Committee, full implementation may cost closer to $300 million. After factoring in “training, staffing, [and] building things like classrooms,” he says, $75 million simply may not be enough. But any more substantial funding seems unlikely to materialize: in a recent budget, the White House sought nearly $300 million to fund improvements related to the law, of which only $23 million was earmarked for programming.

The DOJ prioritized transfers for people deemed to pose a “minimum” risk of recidivism under a new system developed for the First Step Act. But that system, called “PATTERN,” has never been perfect, and appears to have been quietly revised to make it more difficult to reach a “minimum” score — and by extension, that much harder to win a transfer to home confinement. This revelation offers the latest example of how the First Step Act’s implementation has proceeded in fits and starts.

Before imprisoned people can use “time credits” they’ve earned from prison programming, two conditions must be met. First, if they’re seeking a transfer to a halfway house, there must be a bed available. That’s not a sure thing, especially after a round of budget cuts by the Trump administration. Second, an incarcerated person must demonstrate that their risk of committing a new crime is low, as calculated by PATTERN.

The process of developing that tool has not gone smoothly. The first version unveiled by the DOJ, in July 2019, appeared to use a method for calculating “risk” that overstated the actual risk of re-offending among formerly incarcerated people, exaggerated racial disparities, and gave people only marginal credit for completing education, counseling, and other programs while in prison. Taken together, the tool gave short shrift to the idea that people can change while in prison — the very premise of the First Step Act.

Early this year, the DOJ shared what seemed like good news: PATTERN, it said, had been improved to partially address some of the concerns raised by the Brennan Center and others. But the tool continued to use an overly broad definition of recidivism. And while the DOJ claimed it introduced changes to reduce racial disparities, it did not release data on the revised tool’s actual effect on racial disparities. As a result, imprisoned people, families, lawyers, and advocates were all concerned when the DOJ announced it would use PATTERN to help determine who would be transferred out of federal prison during the pandemic.

Those concerns were justified. It now seems that the BOP changed PATTERN more significantly than they initially disclosed to make it much harder to qualify as a “low” or “minimum” risk. (A DOJ report, released a week after ProPublica’s story, suggests that the impact of these changes was relatively small, but offers limited data, and — still — provides no analysis of racial disparities.) This change will certainly narrow the effect of the First Step Act. But more urgently, it seems likely to keep more people in federal prison, exposed to a heightened risk of catching a deadly disease.

Trump has repeatedly claimed credit for passing the First Step Act. He did the same in a Super Bowl ad. Now his administration needs to do the hard work of ensuring that the law lives up to its promise.

“Mandatory minimum sentences are also unlikely to reduce crime by incapacitation, at least given the overbreadth of such laws and their failure to focus on those most likely to recidivate. Among other things, offenders typically age out of the criminal lifestyle, usually in their 30s, meaning that long mandatory sentences may require the continued incarceration of individuals who would not be engaged in crime. In such cases, the extra years of imprisonment will not incapacitate otherwise active criminals and thus will not result in reduced crime. … Moreover, certain offenses subject to mandatory minimums can draw upon a large supply of potential participants. With drug organizations, for instance, an arrested dealer or courier may be quickly replaced by another, eliminating any crime-reduction benefit. More generally, any incapacitation-based effect from mandatory minimums was likely achieved years ago, due to the diminishing marginal returns of locking more people up in an age of mass incarceration. Based on the foregoing arguments and others, most scholars have rejected crime-control arguments for mandatory sentencing laws. By virtually all measures, there is no reason to believe that mandatory minimums have any meaningful impact on crime rates.”

“The conclusion that increasing already long sentences has no material deterrent effect also has implications for mandatory minimum sentencing. Mandatory minimum sentence statutes have two distinct properties. One is that they typically increase already long sentences, which we have concluded is not an effective deterrent. Second, by mandating incarceration, they also increase the certainty of imprisonment given conviction. Because, as discussed earlier, the certainty of conviction even following commission of a felony is typically small, the effect of mandatory minimum sentencing on certainty of punishment is greatly diminished. Furthermore, as discussed at length by Nagin (2013a, 2013b), all of the evidence on the deterrent effect of certainty of punishment pertains to the deterrent effect of the certainty of apprehension, not to the certainty of postarrest outcomes (including certainty of imprisonment given conviction). Thus, there is no evidence one way or the other on the deterrent effect of the second distinguishing characteristic of mandatory minimum sentencing (Nagin, 2013a, 2013b).”

Tonry, Michael. “Fifty Years of American Sentencing Reform — Nine Lessons.” 7 Dec. 2018, Crime and Justice—A Review of Research. Forthcoming. Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=3297777

“Mandatory Sentences. Mandatory sentencing laws should be repealed, and no new ones enacted; they produce countless injustices, encourage cynical circumventions, and seldom achieve demonstrable reductions in crime.

“Mandatory sentencing laws are a fundamentally bad idea. From eighteenth century England, when pickpockets worked the crowds at hangings of pickpockets and juries refused to convict people of offenses subject to severe punishments, to twenty-first century America, the evidence has been clear. Mandatory minimum sentences have few if any discernible deterrent effects and, because of their rigidity, result in unjustly harsh punishments in many cases and willful circumvention by prosecutors, judges, and juries in others. In our time, when plea bargaining is ubiquitous, mandatories are routinely used to coerce guilty pleas, sometimes from innocent people (Johnson 2019).

‘Knowledge about mandatory minimum sentences has changed remarkably little in the past 30 years. Their ostensible primary rationale is deterrence. The overwhelming weight of the evidence, however, shows that they have few if any deterrent effects … Existing knowledge is too fragmentary [and] estimated effects are so small or contingent on particular circumstances as to have no practical relevance for policy making. (Travis, Western, and Redburn 2014, p. 83)’

“Contemporary research thus confirms longstanding cautions against enactment of mandatory sentencing laws. Their use to coerce guilty pleas is new and distinctive to our times. Even innocent defendants are sorely tempted to plead guilty and accept probation or a short prison term rather than risk a mandatory 10- or 20-year sentence. The late Harvard Law School professor William Stuntz observed that ‘outside the plea-bargaining process’ prosecutors’ threats to file charges subject to mandatories ‘would be deemed extortionate’ (2011, p. 260). Federal Court of Appeals judge Gerald Lynch similarly observed that prosecutors’ power to threaten mandatories has enabled them to displace judges from their traditional role: It is ‘the prosecutor who decides what sentence the defendant should be given in exchange for his plea’ (2003, p. 1404). American sentencing has become more severe in recent decades; prosecutors bear much of the responsibility (Johnson 2019).

“Every authoritative law reform organization that has examined American sentencing in the last 50 years has proposed elimination of mandatory minimum sentence laws. These included, in earlier times, the 1967 President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, the 1971 National Commission on Reform of Federal Laws, the 1973 National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, the 1979 Model Sentencing and Corrections Act proposed by the Uniform Law Commissioners, and the American Bar Association’s 1994 Sentencing Standards. The American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code—Sentencing offered the same recommendation in 2017 (Reitz and Klingele 2019).”

Considerable empirical research has shown that racial disparities in sentencing are pervasive: “one of every nine black men between the ages of twenty and thirty-four is behind bars.” In United States v. Booker, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered the mandatory guidelines merely advisory. This study, looking not just at judicial opinions but also at plea agreements, charging decisions, and other factors contributing to sentencing, shows that this racial disparity has actually not increased since more judicial discretion was permitted. Instead, the black-white gap in sentencing “appears to stem largely from prosecutors’ charging choices, especially to charge defendants with ‘mandatory minimum’ offenses.” Removing these minimums as advisory guidelines would help shift toward greater racial equalization in the sentencing arena.

“Despite substantial expenditures on longer prison terms for drug offenders, taxpayers have not realized a strong public safety return. The self-reported use of illegal drugs has increased over the long term as drug prices have fallen and purity has risen. Federal sentencing laws that were designed with serious traffickers in mind have resulted in lengthy imprisonment of offenders who played relatively minor roles. These laws also have failed to reduce recidivism. Nearly a third of the drug offenders who leave federal prison and are placed on community supervision commit new crimes or violate the conditions of their release—a rate that has not changed substantially in decades.”

The government argued that the safety valve criteria under the First Step Act of 2018 was to be read in the disjunctive. The Act was amended in 2018 to change 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)(1) from allowing no more than 1 criminal history point if: (1) the defendant does not have – (A) more than 4 criminal history points . . . ; (B) a prior 3-point offense . . . ; and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense [emphasis added] The district court recognized that the ability to sentence below the guidelines turned on Lopez’s argument that the statute required all three in the conjunctive as opposed to the government’s position. Lopez was eligible for safety-valve relief under the district court’s conjunctive interpretation because, while he had a prior 3-point offense, he did not also have the other two criteria. The court then sentenced him to four years (48 months) of imprisonment. This was one (1) year less than the five-year (60 month) mandatory minimum. The government timely appealed.

The thrust of the argument lay with the fact that the Court determined that Section 3553(f)(1) is “a conjunctive negative proof.” Lopez at 436. To be eligible for the safety valve, a defendant must prove that he or she does not have the following: (A) more than four criminal-history points, (B) a prior three-point offense, and (C) a prior two-point violent offense. See id.

The Court found that this was the opposite of what was intended by Congress with the First Step Act. Congress intended the statute to “allow judges to … use their discretion to craft an appropriate sentence that will fit the crime.” See Lopez at fn. 6.

The government argued that the conjunctive could produce “absurd” results. The government pointed out that a career offender with several drug convictions – but who did not have a violent act conviction – could be eligible for safety-valve relief under a conjunctive interpretation. Id. at 438–39. The Court disagreed that the hypothetical would lead to “absurd” results. The Court found that a conjunctive interpretation results in § 3553(f)(1) not barring non-violent repeat drug offenders from a safety-valve application while violent repeat drug offenders will almost always be barred. Id. at 439. In another footnote, though, the Court dealt with the career hypothetical even more succinctly, noting that if a career drug offender did qualify for safety valve relief, a district court would still retain discretion to sentence the career drug offender above the mandatory-minimum sentence. Id. at fn. 8.

In sum, the majority stated that “courts must presume that a legislature says in a statute what it means and means in a statute what is says there…too many reasons – plain meaning, structure, the Senate’s own legislative drafting manual, and consistent interpretations” support its conclusion that § 3553(f)(1)’s “and” is unambiguously conjunctive. See Lopez at 441. Further, they noted that § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language could possibly result in more defendants receiving safety-valve relief than some in Congress anticipated…but sometimes Congress uses words that reach further than some members of Congress may have expected and Congress has “the authority to amend the statue accordingly” if “and” was supposed to be “or.” Id. at 444.

Circuit Judge Smith wrote an opinion concurring in part and dissenting in part. The opinion focuses on the majority’s analysis of parts (B) and (C). Judge Smith focused on the fact that the Guidelines separate those two classes of convictions and the First Step Act included language stating this in § 3553(f)(1)(C)- a prior 2-point violent offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines. He therefore agreed with the government that a conjunctive interpretation of “and” renders subsection (A) surplusage but also agreed with the majority that this superfluity does not change the outcome. Id. at 446.

Judge Smith’s opinion concludes that Congress may very well have intended that the safety valve exclude only a very specific subset of individuals or that there was something particularly disqualifying about having both a prior two-point violent offense and a prior three-point offense. Id. at 447.

In sum, Lopez clarifies and changes the scope of who may qualify for safety valve relief and practically who does not qualify – individuals with 4 total points, a 3-point offense and a 2-point violent offense. It’s time to ensure we evaluate our cases closely. Although, as the majority and dissent pointed out, just because they qualify does not mean that a judge does not retain the discretion to sentence above the mandatory minimum.

Brock Benjamin is the owner of the Benjamin Law Firm in El Paso that focuses on federal criminal defense in New Mexico and Texas and state criminal defense in Texas. He a director for NMCDLA. Prior to opening the firm, Brock was an assistant District Attorney in El Paso, Texas and immediately following law school was an associate doing legal malpractice plaintiff’s representation. His former life consisted of jumping out of planes in the 2d Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment. He’s an active private pilot and enjoys trips with his family. He can be reached at or 915-412-5858.

Proposed in March 2013, the Justice Safety Valve Act would allow federal judges to hand down sentences below current mandatory minimums if: The mandatory minimum sentence would not accomplish the goal that a sentence be sufficient, but not greater than necessary

The factors the judged considered in arriving at the lower sentence are put in writing and must be based on the language is based on the language of 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a)

This proposed updated safety valve would apply to any federal conviction that has been prescribed a mandatory minimum sentence. As written, it would not apply retroactively; inmates already serving a mandatory minimum sentence would not be allowed to request a lesser sentence or re-sentencing based on the Act. It would only apply to federal sentencing; North Carolina would have to enact its own legislation to change state mandatory minimum sentencing.

In addition to these statistics, the application of mandatory minimum sentences leads to absurdly long sentences being imposed, at great taxpayer expense, on non-violent individuals. The organization Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM) details how mandatory minimums have resulted in substantial – and unfair – punishments for low-level crimes, including these two examples: Weldon Angelos: Mr. Angelos was sentenced to 55 years in prison after making several small drug sales to a government informant. Several weapons were found in his home and the informant reported seeing a weapon in Mr. Angelos’ possession during at least two buys. He was charged with several counts of possessing a gun during a drug trafficking offense, leading to the substantial sentence, despite having no major criminal record, dealing only in small amounts of weed, and never using a weapon during the course of a drug transaction.

John Hise: Mr. Hise was sentenced to 10 years on a drug conspiracy charge. He had sold red phosphorous to a friend who was involved in meth manufacturing. Mr. Hise stopped aiding his friend, but not before authorities had caught on. He was convicted and sentenced to 10 years despite police finding no evidence of red phosphorous in his home during a search. Mr. Hise was ineligible for the current safety valve law because of a possession and DUI offense already on his record.

The use of mandatory minimums that allow little discretion for judges to depart to a lower sentence have contributed to the growing prison population and expense of housing those arbitrarily required to spend years in prison. There is certainly room for improvement. Expanding this safety valve to all mandatory minimum sentences would reduce the long-term prison population while still ensuring that the goals of sentencing are met.

The first question a federal judge must consider in deciding whether or not he or she will sentence a person convicted of a federal offense below the mandatory minimum under the proposed Act is whether the mandatory minimum sentence would over punish that person. In other words, would the mandatory minimum put the person in prison for longer than is necessary to meet the goals of sentencing?

The proposed Act would ensure that the goals of sentencing return to the forefront of determining an appropriate prison term rather than substituting the judgment of Congress for that of the presiding judge during the sentencing phase of the federal criminal process.

There are currently just under 200 mandatory minimum sentences for federal crimes on the books, but only federal drug offenses are subject to an existing sentencing safety valve. The actual text of the existing sentencing safety valve can be found at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In order for a federal judge to apply the existing safety valve to sentencing for a federal drug crime, he or she must make the following findings: No one was injured during the commission of the drug offense

These criteria are strict and minimize the number of people who could be saved from lengthy, arbitrary prison sentences. The legal possession of a gun during the commission of a drug crime has been used to deny the application of the safety valve as has prior criminal history that included only misdemeanor or petty offenses. In effect, the current safety valve legislation allows only about one-quarter of those sentenced on federal drug offenses to take advantage of the deviation from mandatory minimums each year.

Another exception to mandatory minimum sentencing, substantial assistance, is often unavailable to low-level drug offenders. Often those who are tasked with transporting or selling drugs, or who are considered mules, have little if any information about the actual drug ring itself. These people are then not eligible for a reduced sentence below a mandatory minimum because they have no information to provide prosecutors; they are incapable of providing substantial assistance.

Identical versions of the Act were introduced in the House and Senate, H.R. 1695 and S. 619. Both have been referred to the committee for review. The proposed Safety Valve Act would expand the application of the safety valve beyond drug crimes and would allow judges to ensure that sentencing goals are met while not over-punishing individuals and overcrowding the nation’s prison system.

However, the Safety Valve Act is no substitute for an experienced federal defense lawyer on the side of anyone facing federal charges; it is not a get out of jail card. If a judge deviates below mandatory minimums in sentencing, he or she would still be required to apply the federal sentencing guidelines in determining an appropriate sentence.

This informational article about the proposed Justice Safety Valve Act is provided by the attorneys of Roberts Law Group, PLLC, a criminal defense law firm dedicated to the rights of those accused of a crime throughout North Carolina. To learn more about the firm, please like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter or Google+ to get the latest updates on safety and criminal defense matters in North Carolina. For a free consultation with a Charlotte defense lawyer from Roberts Law Group, please call contact our law firm online.

In this case, our client was charged with First Degree Murder in connection with a “drive-by” shooting that occurred in Charlotte, NC. The State’s evidence included GPS ankle monitoring data linking our client was at the scene of the crime and evidence that our client confessed to an inmate while in jail. Nonetheless, we convinced a jury to unanimously find our client Not Guilty. He was released from jail the same day.

Our client was charged with First Degree for the shooting death related to alleged breaking and entering. The State’s evidence included a co-defendant alleging that our client was the shooter. After conducting a thorough investigation with the use of a private investigator, we persuaded the State to dismiss entirely the case against our client.

After conducting an investigation and communicating with the prosecutor about the facts and circumstances indicating that our client acted in self-defense, the case was dismissed and deemed a justifiable homicide.

Our client was charged with the First Degree Murder of a young lady by drug overdose. After investigating the decedent’s background and hiring a preeminent expert toxicologist to fight the State’s theory of death, we were able to negotiate this case down from Life in prison to 5 years in prison, with credit for time served.

Our client was charged with First Degree Murder related to a “drug deal gone bad.” After engaging the services of a private investigator and noting issues with the State’s case, we were able to negotiate a plea for our client that avoided a Life sentence and required him to serve only 12 years.

On behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, we write to urge you to vote YES on S. 756, the FIRST STEP Act. This legislation is a next step towards desperately needed federal criminal justice reform, but for all its benefits, much more needs to be done. The inclusion of concrete sentencing reforms in the new and improved Senate version of the FIRST STEP Act is a modest improvement, but many people will be left in prison to serve long draconian sentences because some provisions of the legislation are not retroactive. The revised FIRST STEP Act, however, is not without problems. The bill continues to exclude individuals from benefiting from some provisions based solely on their prior offenses, namely citizenship and immigration status, as well as certain prior drug convictions and their “risk score” as determined by a discriminatory risk assessment system. While these concerns remain a priority for our organizations and we will advocate for improvements in the future, ultimately the improvements to the federal sentencing scheme will have a net positive impact on the lives of some of the people harmed by our broken justice system and we urge you to vote YES on S. 756. The ACLU and The Leadership Conference will include your votes on our updated voting scorecards for the 115th Congress.

While the dollar amounts are astounding, the toll that our U.S. criminal justice policies have taken on black and brown communities across the nation goes far beyond the enormous amount of money that is spent. This country’s extraordinary incarceration rates impose much greater costs than simply the fiscal expenditures necessary to incarcerate over 20 percent of the world’s prisoners. The true costs of this country’s addiction to incarceration must be measured in human lives and particularly the generations of young black and Latino men who serve long prison sentences and are lost to their families and communities. The Senate version of the FIRST STEP Act makes some modest improvements to the current federal system.

I. Sentencing Reform Changes to House-passed FIRST STEP Act–Sentencing reform is the key to slowing down the flow of people going into our prisons. This makes sentencing reform pivotal to addressing mass incarceration, prison overcrowding, and the exorbitant costs of incarceration. As a result of our coalition’s advocacy, the new FIRST STEP Act added some important sentencing reform provisions from SRCA, which will aid us in tackling these issues on the federal level.[x] These important changes in federal law will result in fewer people being subjected to harsh mandatory minimums.

Expands the Existing Safety Valve. The revised bill expands eligibility for the existing safety valve under 18 U.S.C 3553(f)[xi] from one to four criminal history points if a person does not have prior 2-point convictions for crimes of violence or drug trafficking offenses and prior 3-point convictions. Under the expanded safety valve, judges will have discretion to make a person eligible for the safety valve in cases where the seriousness of his or her criminal history is over-represented, or it is unlikely he or she would commit other crimes. This crucial expansion of the safety valve will reduce sentences for an estimated 2,100 people per year.[xii]

Retroactive Application of Fair Sentencing Act (FSA). The new version of FIRST STEP Act would retroactively apply the statutory changes of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (FSA), which reduced the disparity in sentence lengths between crack and powder cocaine. This change in the law will allow people who were sentenced under the harsh and discriminatory 100 to 1 crack to powder cocaine ratio to be resentenced under the 2010 law.[xiii] This long overdue improvement would allow over 2,600 people the chance to be resentenced.[xiv]

Reforms the Unfair Two-Strikes and Three-Strikes Laws. The new version of FIRST STEP would reduce the impact of certain mandatory minimums. It would reduce the mandatory life sentence for a third drug felony to a mandatory minimum sentence of 25 years and reduce the 20-year mandatory minimum for a second drug felony to 15 years.

II. Prison Reform Changes to House-passed FIRST STEP Act, H.R. 3356–The revised bill also made some strides in improving some of the problematic prison reform provisions. The new bill strengthened oversight over the new risk assessment system, limited the discretion of the attorney general, and increased funding for prison programming, among other things. The bill now does the following:

Permits Early Community Release and Loosens Restrictions on Home Confinement.The House-passed FIRST STEP Act limited the use of earned credits to time in prerelease custody (halfway house or home confinement). The revised bill would expand the use of earned credits to supervised release in the community. The bill also would permit individuals in home confinement to participate in family-related activities that facilitate the prisoner’s successful reentry.

Reauthorizes Second Chance Act. The revised bill reauthorizes the Second Chance Act, which provides federal funding for drug treatment, vocational training, and other reentry and recidivism programming.

While these revisions to the bill were critical to garnering our support, we must acknowledge that some of the more concerning aspects of the House-passed version of the FIRST STEP Act remain.

III. Outstanding Concerns Regarding the FIRST STEP Act–The bill continues to exclude too many people from earning time credits, including those convicted of immigration-related offenses. It does not retroactively apply its sentencing reform provisions to people convicted of anything other than crack convictions, continues to allow for-profit companies to benefit off of incarceration, fails to address parole for juveniles serving life sentences in federal prison, and expands electronic monitoring.

Fails to Include Retroactivity for Enhanced Mandatory Minimum Sentences for Prior Drug Offenses &. 924(c) “stacking.”The bill does not include retroactivity for its sentencing reforms besides the long-awaited retroactivity for the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010. This minimizes the overall impact substantially. Retroactivity is a vital part of any meaningful sentencing reform. Not only does it ensure that the changes we make to our criminal justice system benefit the people most impacted by it, but it’s also one of the essential policy changes to reduce mass incarceration. The federal prison population has fallen by over 38,000[xvi] since 2013 thanks in large part to retroactive application of sentencing guidelines approved by the U.S. Sentencing Commission.[xvii] More than 3,000 people will be left in prison without retroactive application of the “three strikes” law and the change to the 924 (c) provisions in the FIRST STEP Act.[xviii]

Excludes Too Many Federal Prisoners from New Earned Time Credits. The bill continues to exclude many federal prisoners from earning time credits and excludes many federal prisoners from being able to “cash in” the credits they earn. The long list of exclusions in the bill sweep in, for example, those convicted of certain immigration offenses and drug offenses.[xix] Because immigration and drug offenses account for 53.3 percent of the total federal prison population, many people could be excluded from utilizing the time credits they earned after completing programming.[xx] The continued exclusion of immigrants from the many benefits of the bill simply based on immigration status is deeply troubling. The Senate version of FIRST STEP maintains a categorical exclusion of people convicted of certain immigration offenses from earning time credits under the bill. The new version of the bill also bars individuals from using the time credits they have earned if they have a final order of removal. More than 12,000 people are currently in federal prison for immigration offenses and are disproportionately people of color.[xxi] Thus, a very large number of people in federal prison would not reap the benefits proposed in this bill and a disproportionate number of those excluded would be people of color. Denying early-release credits to certain people also reduces their incentive to complete the rehabilitative programs and contradicts the goal of increasing public safety. Any reforms enacted by Congress should impact a significant number of people in federal prison and reduce racial disparities or they will have little effect on the fiscal and human costs of incarceration.

Allows Private Prison Companies to Profit. The bill also maintains concerning provisions that could privatize government functions and allow the Attorney General excessive discretion. FIRST STEP provides that in order to expand programming, BOP shall enter into partnerships with private organizations and companies under policies developed by the Attorney General, “subject to appropriations.” This could result in the further privatization of what should be public functions and would allow private entities to unduly profit from incarceration.

Fails to Include Parole for Juveniles, Sealing and Expungement. Under SRCA, judges would have discretion to reduce juvenile life without parole sentences after 20 years. It would also permit some juveniles to seal or expunge non-violent convictions from their record. The FIRST STEP Act does not address these important bipartisan provisions.

Bringing fairness and dignity to our justice system is one of the most important civil and human rights issues of our time. The revised version of the FIRST STEP Act is a modest, but important move towards achieving some meaningful reform to the criminal legal system. While the bill continues to have its problems, and we will fight to address those in the future, it does include concrete sentencing reforms that would impact people’s lives. For these reasons, we urge you to vote YES on S. 756.

Ultimately, the First Step Act is not the end– it is just the next in a series of efforts over the past 10 years to achieve important federal criminal justice reform. Congress must take many more steps to undo the harms of the tough on crime policies of the 80’s and 90’s – to create a system that is just and equitable, significantly reduces the number of people unnecessarily entering the system, eliminates racial disparities, and creates opportunities for second chances.

If you have any additional questions, please feel free to contact Jesselyn McCurdy, Deputy Director, ACLU Washington Legislative Office, at [email protected] or (202) 675-2307 or Sakira Cook, Director, Justice Program, The Leadership Conference, at [email protected] or (202) 263-2894.

[vii] See Tracy Kyckelhahn, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Justice Expenditure and Employment Extracts, 2012,Preliminary Tbl. 1 (2015), https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5239 (showing FY 2012 state and federal corrections expenditure was $80,791,046,000).

[xi] A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). See 18 U.S.C. 3553(f) (2010)

[xii] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

[xiii] Although the ACLU supported the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, we would ultimate support a change in law that would treat crack and powder cocaine equally; 1 to 1 ratio.

[xiv] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

[xviii] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

8613371530291

8613371530291