first step act safety valve pricelist

“Mandatory minimum sentences are also unlikely to reduce crime by incapacitation, at least given the overbreadth of such laws and their failure to focus on those most likely to recidivate. Among other things, offenders typically age out of the criminal lifestyle, usually in their 30s, meaning that long mandatory sentences may require the continued incarceration of individuals who would not be engaged in crime. In such cases, the extra years of imprisonment will not incapacitate otherwise active criminals and thus will not result in reduced crime. … Moreover, certain offenses subject to mandatory minimums can draw upon a large supply of potential participants. With drug organizations, for instance, an arrested dealer or courier may be quickly replaced by another, eliminating any crime-reduction benefit. More generally, any incapacitation-based effect from mandatory minimums was likely achieved years ago, due to the diminishing marginal returns of locking more people up in an age of mass incarceration. Based on the foregoing arguments and others, most scholars have rejected crime-control arguments for mandatory sentencing laws. By virtually all measures, there is no reason to believe that mandatory minimums have any meaningful impact on crime rates.”

“The conclusion that increasing already long sentences has no material deterrent effect also has implications for mandatory minimum sentencing. Mandatory minimum sentence statutes have two distinct properties. One is that they typically increase already long sentences, which we have concluded is not an effective deterrent. Second, by mandating incarceration, they also increase the certainty of imprisonment given conviction. Because, as discussed earlier, the certainty of conviction even following commission of a felony is typically small, the effect of mandatory minimum sentencing on certainty of punishment is greatly diminished. Furthermore, as discussed at length by Nagin (2013a, 2013b), all of the evidence on the deterrent effect of certainty of punishment pertains to the deterrent effect of the certainty of apprehension, not to the certainty of postarrest outcomes (including certainty of imprisonment given conviction). Thus, there is no evidence one way or the other on the deterrent effect of the second distinguishing characteristic of mandatory minimum sentencing (Nagin, 2013a, 2013b).”

Tonry, Michael. “Fifty Years of American Sentencing Reform — Nine Lessons.” 7 Dec. 2018, Crime and Justice—A Review of Research. Forthcoming. Available at SSRN:https://ssrn.com/abstract=3297777

“Mandatory Sentences. Mandatory sentencing laws should be repealed, and no new ones enacted; they produce countless injustices, encourage cynical circumventions, and seldom achieve demonstrable reductions in crime.

“Mandatory sentencing laws are a fundamentally bad idea. From eighteenth century England, when pickpockets worked the crowds at hangings of pickpockets and juries refused to convict people of offenses subject to severe punishments, to twenty-first century America, the evidence has been clear. Mandatory minimum sentences have few if any discernible deterrent effects and, because of their rigidity, result in unjustly harsh punishments in many cases and willful circumvention by prosecutors, judges, and juries in others. In our time, when plea bargaining is ubiquitous, mandatories are routinely used to coerce guilty pleas, sometimes from innocent people (Johnson 2019).

‘Knowledge about mandatory minimum sentences has changed remarkably little in the past 30 years. Their ostensible primary rationale is deterrence. The overwhelming weight of the evidence, however, shows that they have few if any deterrent effects … Existing knowledge is too fragmentary [and] estimated effects are so small or contingent on particular circumstances as to have no practical relevance for policy making. (Travis, Western, and Redburn 2014, p. 83)’

“Contemporary research thus confirms longstanding cautions against enactment of mandatory sentencing laws. Their use to coerce guilty pleas is new and distinctive to our times. Even innocent defendants are sorely tempted to plead guilty and accept probation or a short prison term rather than risk a mandatory 10- or 20-year sentence. The late Harvard Law School professor William Stuntz observed that ‘outside the plea-bargaining process’ prosecutors’ threats to file charges subject to mandatories ‘would be deemed extortionate’ (2011, p. 260). Federal Court of Appeals judge Gerald Lynch similarly observed that prosecutors’ power to threaten mandatories has enabled them to displace judges from their traditional role: It is ‘the prosecutor who decides what sentence the defendant should be given in exchange for his plea’ (2003, p. 1404). American sentencing has become more severe in recent decades; prosecutors bear much of the responsibility (Johnson 2019).

“Every authoritative law reform organization that has examined American sentencing in the last 50 years has proposed elimination of mandatory minimum sentence laws. These included, in earlier times, the 1967 President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, the 1971 National Commission on Reform of Federal Laws, the 1973 National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals, the 1979 Model Sentencing and Corrections Act proposed by the Uniform Law Commissioners, and the American Bar Association’s 1994 Sentencing Standards. The American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code—Sentencing offered the same recommendation in 2017 (Reitz and Klingele 2019).”

Considerable empirical research has shown that racial disparities in sentencing are pervasive: “one of every nine black men between the ages of twenty and thirty-four is behind bars.” In United States v. Booker, the U.S. Supreme Court rendered the mandatory guidelines merely advisory. This study, looking not just at judicial opinions but also at plea agreements, charging decisions, and other factors contributing to sentencing, shows that this racial disparity has actually not increased since more judicial discretion was permitted. Instead, the black-white gap in sentencing “appears to stem largely from prosecutors’ charging choices, especially to charge defendants with ‘mandatory minimum’ offenses.” Removing these minimums as advisory guidelines would help shift toward greater racial equalization in the sentencing arena.

“Despite substantial expenditures on longer prison terms for drug offenders, taxpayers have not realized a strong public safety return. The self-reported use of illegal drugs has increased over the long term as drug prices have fallen and purity has risen. Federal sentencing laws that were designed with serious traffickers in mind have resulted in lengthy imprisonment of offenders who played relatively minor roles. These laws also have failed to reduce recidivism. Nearly a third of the drug offenders who leave federal prison and are placed on community supervision commit new crimes or violate the conditions of their release—a rate that has not changed substantially in decades.”

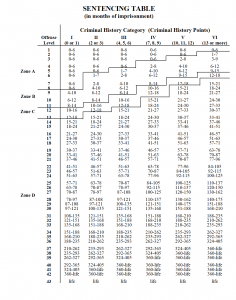

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

Although the First Step Act has been stalled in the Senate for more than five months since passing the House earlier this year by a vote of 360 to 59, the bill is very much alive, as the lame duck session of the 115th Congress gets underway. News broke this week that a final deal that incorporates the input of key Senate and House players, outside stakeholders, and the White House has been put on the table.

{mosads}The First Step Act that passed the House focused on only prison reform, a priority outlined by President Trump in his State of the Union Address this year and that has continued to press on since. The majority of the 57 Democrats who voted against the House bill did so because they did not think prison reform was enough. They want sentencing reforms as well.

Many in the Senate shared that perspective, so this dream has finally become a reality. The package proposed includes the bill passed by the House with a few important revisions as well as four sentencing provisions the Senate knows well. These are the 924(c) stacking reform, 841/851 sentencing enhancement modifications, expansion of the 3553(f) federal safety valve, and retroactive application of the Fair Sentencing Act.

Leading on the issue in the White House is Jared Kushner and his team at the Office of American Innovation. For their tireless work to deliver relief to thousands of Americans affected by the inefficient federal justice system and continue to keep our communities safe, they deserve endless credit. McConnell now has a bill to do a vote check on, which he has promised to do, that has the backing of Senators Mike Lee (R-Utah), Tim Scott (R-S.C.), and Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) and everywhere around and in between, and that has wide support from faith based leaders and law enforcement alike. This new bill is dubbed the First Step Act.

For lawmakers, passing the First Step Act in the lame duck session this year is the smartest move imaginable. In a time when the American people feel that bipartisanship is a thing of the past and all that occurs in Washington anymore is gridlock and partisan vitriol, nothing could be better for all members of Congress than to prove that they can reach across the aisle in good faith for the betterment of the country.

The merits of the First Step Act compromise package in the Senate stand on their own legs. Carefully crafted criminal justice reforms that provide modest but meaningful incentives to prisoners to participate in evidence based programming individually designed to reduce their risk of reoffense upon release from prison is all but entirely noncontroversial legislation. In the House, only two Republicans voted against the original bill.

On the sentencing side of the equation, the proposed reforms in the First Step Act apply the law as it was intended, refocus lengthy sentences on serious offenders, allow judges to exercise some discretion in sentencing offenders with limited and lower level criminal history, and offer relief to thousands of inmates at no cost to public safety. Although the lowest hanging fruit of sentencing changes included in bills that have been discussed for years, including the Smarter Sentencing Act and the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, these reforms effectively tackle some of the most egregious and obvious wrongs of our sentencing laws.

Senators should look to their backyards at home for proof that these reforms work. States, both traditionally conservative and traditionally liberal alike, have implemented criminal justice reforms over the past decade that serve as the model for the reforms in the First Step Act. An impressive 35 states have successfully cut crime and imprisonment simultaneously, and 22 of those states did so by double digits for both.

Clearly, this is a winning issue for conservatives, liberals, and Americans across the country. The Senate has a historic chance to break from its usual pattern on legislation and do its part in passing meaningful reform of our criminal justice system. With a House willing to support such significant reforms and a president who understands what this means not only to those in direct contact with the criminal justice system but also to average Americans, the time is now to pass the First Step Act.

The Eleventh Circuit has again landed on the wrong side of a circuit split. In the First Step Act, Congress expanded the pool of people eligible for the safety valve, which allows a judge to dive below the mandatory minimum in a drug case. In the past, a person was eligible only if he had zero or one criminal history points under the sentencing guidelines. But now, the fresh version of 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)(1) says a person is eligible so long as:

Does “and” really mean “and”? Must the government prove all three disqualifiers? In So if you fit into any one of the subsections, you must be denied safety-valve treatment. The holding has provoked a circuit split with United States v. Lopez, 2021 WL 2024540 (9th Cir. May 21, 2021). One side note: Judge Branch, in her Garconconcurrence, and the Lopezpanel both cited the very same pages of Scalia and Garner’s Reading Law, but read the same words to have opposite meanings.

Solutions: Shift funding from local or state public safety budgets into a local grant program to support community-led safety strategies in communities most impacted by mass incarceration, over-policing, and crime. States can use Colorado’s “Community Reinvestment” model. In fiscal year 2021-22 alone, four Community Reinvestment Initiatives will provide $12.8 million to community-based services in reentry, harm reduction, crime prevention, and crime survivors.

More information: See details about the CAHOOTS program. For a review of other strategies ranging from police-based responses to community-based responses, see the Vera Institute of Justice’s Behavioral Health Crisis Alternatives, the Brookings Institute’s Innovative solutions to address the mental health crisis, and The Council of State Governments’ Expanding First Response: A Toolkit for Community Responder Programs.

Reclassify criminal offenses and turn misdemeanor charges that don’t threaten public safety into non-jailable infractions, or decriminalize them entirely.

More information:For information on the youth justice reforms discussed, see The National Conference of State Legislatures Juvenile Age of Jurisdiction and Transfer to Adult Court Laws; the recently-closed Campaign for Youth Justice resources summarizing legislative reforms to Raise the Age, limit youth transfers, and remove youth from adult jails (available here and here); Youth First Initiative’s No Kids in Prison campaign; and The Vera Institute of Justice’s Status Offense Toolkit.

Legislation: Tennessee SB 0985/ HB 1449 (2019) and Massachusetts S 2371 (2018) permit or require primary caregiver status and available alternatives to incarceration to be considered for certain defendants prior to sentencing. New Jersey A 3979 (2018) requires incarcerated parents be placed as close to their minor child’s place of residence as possible, allows contact visits, prohibits restrictions on the number of minor children allowed to visit an incarcerated parent, and also requires visitation be available at least 6 days a week.

More information:See Families for Justice as Healing, Free Hearts, Operation Restoration, and Human Impact Partners’ Keeping Kids and Parents Together: A Healthier Approach to Sentencing in MA, TN, LA and the Illinois Task Force on Children of Incarcerated Parents’ Final Report and Recommendations.

Legislation: Illinois Pretrial Fairness Act, HB 3653 (2019), passed in 2021, abolishes money bail, limits pretrial detention, regulates the use of risk assessment tools in pretrial decisions, and requires reconsideration of pretrial conditions or detention at each court date. When this legislation takes effect in 2023, roughly 80% of people arrested in Cook County (Chicago) will be ineligible for pretrial detention.

More information: See The Bail Project’s After Cash Bail, the Pretrial Justice Institute’s website, the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School’s Moving Beyond Money, and Critical Resistance & Community Justice Exchange’s On the Road to Freedom. For information on how the bail industry — which often actively opposes efforts to reform the money bail system — profits off the current system, see our report All profit, no risk: How the bail industry exploits the legal system.

Solutions: States should pass legislation establishing moratoriums on jail and prison construction. Moratoriums on building new, or expanding existing, facilities allow reforms to reduce incarceration to be prioritized over proposals that would worsen our nation’s mass incarceration epidemic. Moratoriums also allow for the impact of reforms enacted to be fully realized and push states to identify effective alternatives to incarceration.

Problem: With approximately 80 percent of criminal defendants unable afford to an attorney, public defenders play an essential role in the fight against mass incarceration. Public defenders fight to keep low-income individuals from entering the revolving door of criminal legal system involvement, reduce excessive sentences, and prevent wrongful convictions. When people are provided with a public defender earlier, such as prior to their first appearance, they typically spend less time in custody. However, public defense systems are not adequately resourced; rather, prosecutors and courts hold a disproportionate amount of resources. The U.S. Constitution guarantees legal counsel to individuals who are charged with a crime, but many states delegate this constitutional obligation to local governments, and then completely fail to hold local governments accountable when defendants are not provided competent defense counsel.

Problem: Nationally, one of every six people in state prisons has been incarcerated for a decade or more. While many states have taken laudable steps to reduce the number of people serving time for low-level offenses, little has been done to bring relief to people needlessly serving decades in prison.

Solutions: State legislative strategies include: enacting presumptive parole, second-look sentencing, and other common-sense reforms, such as expanding “good time” credit policies. All of these changes should be made retroactive, and should not categorically exclude any groups based on offense type, sentence length, age, or any other factor.

Legislation: Federally, S 2146 (2019), the Second Look Act of 2019, proposed to allow people to petition a federal court for a sentence reduction after serving at least 10 years. California AB 2942 (2018) removed the Parole Board’s exclusive authority to revisit excessive sentences and established a process for people serving a sentence of 15 years-to-life to ask the district attorney to make a recommendation to the court for a new sentence after completing half of their sentence or 15 years, whichever comes first. California AB 1245 (2021) proposed to amend this process by allowing a person who has served at least 15 years of their sentence to directly petition the court for resentencing. The National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers has created model legislation that would allow a lengthy sentence to be revisited after 10 years.

Problem: Automatic sentencing structures have fueled the country’s skyrocketing incarceration rates. For example, mandatory minimum sentences, which by the 1980s had been enacted in all 50 states, reallocate power from judges to prosecutors and force defendants into plea bargains, exacerbate racial disparities in the criminal legal system, and prevent judges from taking into account the circumstances surrounding a criminal charge. In addition, “sentencing enhancements,” like those enhanced penalties that are automatically applied in most states when drug crimes are committed within a certain distance of schools, have been shown to exacerbate racial disparities in the criminal legal system. Both mandatory minimums and sentencing enhancements harm individuals and undermine our communities and national well-being, all without significant increases to public safety.

Solutions: The best course is to repeal automatic sentencing structures so that judges can craft sentences to fit the unique circumstances of each crime and individual. Where that option is not possible, states should: adopt sentencing “safety valve” laws, which give judges the ability to deviate from the mandatory minimum under specified circumstances; make enhancement penalties subject to judicial discretion, rather than mandatory; and reduce the size of sentencing enhancement zones.

Legislation: Several examples of state and federal statutes are included in Families Against Mandatory Minimums’ (FAMM) Turning Off the Spigot. The American Legislative Exchange Council has produced model legislation, the Justice Safety Valve Act.

Problem: The release of individuals who have been granted parole is often delayed for months because the parole board requires them to complete a class or program (often a drug or alcohol treatment program) that is not readily available before they can go home. As of 2015, at least 40 states used institutional program participation as a factor in parole determinations. In some states — notably Tennessee and Texas — thousands of people whom the parole board deemed “safe” to return to the community remain incarcerated simply because the state has imposed this bureaucratic hurdle.

Solutions: States should increase the dollar amount of a theft to qualify for felony punishment, and require that the threshold be adjusted regularly to account for inflation. This change should also be made retroactive for all people currently in prison, on parole, or on probation for felony theft.

Problem: Probation and parole are supposed to provide alternatives to incarceration. However, the conditions of probation and parole are often unrelated to the individual’s crime of conviction or their specific needs, and instead set them up to fail. For example, restrictions on associating with others and requirements to notify probation or parole officers before a change in address or employment have little to do with either public safety or “rehabilitation.” Additionally, some states allow community supervision to be revoked when a person is “alleged” to have violated — or believed to be “about to” violate — these or other terms of their supervision. Adding to the problem are excessively long supervision sentences, which spread resources thin and put defendants at risk of lengthy incarceration for subsequent minor offenses or violations of supervision rules. Because probation is billed as an alternative to incarceration and is often imposed through plea bargains, the lengths of probation sentences do not receive as much scrutiny as they should.

Solutions: States should limit incarceration as a response to supervision violations to when the violation has resulted in a new criminal conviction and poses a direct threat to public safety. If incarceration is used to respond to technical violations, the length of time served should be limited and proportionate to the harm caused by the non-criminal rule violation.

More information: Challenging E-Carceration, provides details about the encroachment of electronic monitoring into community supervision, and Cages Without Bars provides details about electronic monitoring practices across a number of U.S. jurisdictions and recommendations for reform. Fact sheets, case studies, and guidelines for respecting the rights of people on electronic monitors are available from the Center for Media Justice.

Solutions: Stop suspending, revoking, and prohibiting the renewal of driver’s licenses for nonpayment of fines and fees. Since 2017, fifteen states (Calif., Colo., Hawaii, Idaho, Ill., Ky., Minn., Miss., Mont., Nev., Ore., Utah, Va., W.Va., and Wyo.) and the District of Columbia have eliminated all of these practices.

More information: See our briefing with national data and state-specific data for 15 states (Colo., Idaho, Ill., La., Maine, Mass., Mich., Miss., Mont., N.M., N.D., Ohio, Okla., S.C., and Wash.) that charge monthly fees even though half (or more) of their probation populations earn less than $20,000 per year. States with privatized misdemeanor probation systems will find helpful the six recommendations on pages 7-10 of the Human Rights Watch report Set up to Fail: The Impact of Offender-Funded Private Probation on the Poor.

Problem: Calls home from prisons and jails cost too much because the prison and jail telephone industry offers correctional facilities hefty kickbacks in exchange for exclusive contracts. While most state prison phone systems have lowered their rates, and the Federal Communications Commission has capped the interstate calling rate for small jails at 21c per minute, many jails are charging higher prices for in-state calls to landlines.

Legislation and regulations: Legislation like Connecticut’s S.B. 972 (2021) ensured that the state — not incarcerated people — pay for the cost of calls. Short of that, the best model is New York Corrections Law S 623 which requires that contracts be negotiated on the basis of the lowest possible cost to consumers and bars the state from receiving any portion of the revenue. (While this law only applied to contracts with state prisons, an ideal solution would also include local jail contracts.) States can also increase the authority of public utilities commissions to regulate the industry (as Colorado did) and California Public Utilities Commission has produced the strongest and most up-to-date state regulations of the industry.

Solutions: States have the power to decisively end this pernicious practice by prohibiting facilities from using release cards that charge fees, and requiring fee-free alternative payment methods.

Problem: Despite a growing body of evidence that medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is effective at treating opioid use disorders, most prisons are refusing to offer those treatments to incarcerated people, exacerbating the overdose and recidivism rate among people released from custody. In fact, studies have stated that drug overdose is the leading cause of death after release from prison, and the risk of death is significantly higher for women.

Legislation and model program: New York SB 1795 (2021) establishes MAT for people incarcerated in state correctional facilities and local jails. In addition, Rhode Island launched a successful program to provide MAT to some of the people incarcerated in their facilities. The early results are very encouraging: In the first year, Rhode Island reported a 60.5% reduction in opioid-related mortality among recently incarcerated people.

Solutions: Change state laws and/or state constitutions to remove disenfranchising provisions. Additionally, governors should immediately restore voting rights to disenfranchised people via executive action when they have the power to do so.

Legislation: D.C. B 23-0324 (2019) ended the practice of felony disenfranchisement for Washington D.C. residents; Hawai’i SB 1503/HB 1506 (2019) would have allowed people who were Hawai’i residents prior to incarceration to vote absentee in Hawai’i elections; New Jersey A 3456/S 2100 (2018) would have ended the practice of denying New Jersey residents incarcerated for a felony conviction of their right to vote.

Problem: Many people who are detained pretrial or jailed on misdemeanor convictions maintain their right to vote, but many eligible, incarcerated people are unaware that they can vote from jail. In addition, state laws and practices can make it impossible for eligible voters who are incarcerated to exercise their right to vote, by limiting access to absentee ballots, when requests for ballots can be submitted, how requests for ballots and ballots themselves must be submitted, and how errors on an absentee ballot envelope can be fixed.

Problem: The Census Bureau’s practice of tabulating incarcerated people at correctional facility locations (rather than at their home addresses) leads state and local governments to draw skewed electoral districts that grant undue political clout to people who live near large prisons and dilute the representation of people everywhere else.

Solutions: States can pass legislation to count incarcerated people at home for redistricting purposes, as Calif., Colo., Conn., Del., Ill., Md., Nev., N.J., N.Y, Va., and Wash. have done. Ideally, the Census Bureau would implement a national solution by tabulating incarcerated people at home in the 2030 Census, but states must be prepared to fix their own redistricting data should the Census fail to act. Taking action now ensures that your state will have the data it needs to end prison gerrymandering in the 2030 redistricting cycle.

Problem: In courthouses throughout the country, defendants are routinely denied the promise of a “jury of their peers,” thanks to a lack of racial diversity in jury boxes. One major reason for this lack of diversity is the constellation of laws prohibiting people convicted (or sometimes simply accused) of crimes from serving on juries. These laws bar more than twenty million people from jury service, reduce jury diversity by disproportionately excluding Black and Latinx people, and actually cause juries to deliberate less effectively. Such exclusionary practices often ban people from jury service forever.

Problem: The impacts of incarceration extend far beyond the time that a person is released from prison or jail. A conviction history can act as a barrier to employment, education, housing, public benefits, and much more. Additionally, the increasing use of background checks in recent years, as well as the ability to find information about a person’s conviction history from a simple internet search, allows for unchecked discrimination against people who were formerly incarcerated. The stigma of having a conviction history prevents individuals from being able to successfully support themselves, impacts families whose loved ones were incarcerated, and can result in higher recidivism rates.

Ensure that people have access to health care benefits prior to release. Screen and help people enroll in Medicaid benefits upon incarceration and prior to release; if a person’s Medicaid benefits were suspended upon incarceration, ensure that they are active prior to release; and ensure people have their medical cards upon release.

Legislation:Rhode Island S 2694 (2022) proposed to: maintain Medicaid enrollment for the first 30 days of a person’s incarceration; require Medicaid eligibility be determined, and eligible individuals enrolled, upon incarceration; require reinstatement of suspended health benefits and the delivery of medical assistance identify cards prior to release from incarceration.

Problem: Four states have failed to repeal another outdated relic from the war on drugs — automatic driver’s license suspensions for all drug offenses, including those unrelated to driving. Our analysis shows that there are over 49,000 licenses suspended every year for non-driving drug convictions. These suspensions disproportionately impact low-income communities and waste government resources and time.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

If you ask some criminal justice reform activists, the 1994 crime law passed by Congress and signed by President Bill Clinton, which was meant to reverse decades of rising crime, was one of the key contributors to mass incarceration in the 1990s. They say it led to more prison sentences, more prison cells, and more aggressive policing — especially hurting Black and brown Americans, who are disproportionately likely to be incarcerated.

If you ask Biden, that’s not true at all. The law, he’s argued on the campaign trail, had little impact on incarceration, which largely happens at the state level. As recently as 2016, Biden defended the law, arguing it “restored American cities” following an era of high crime and violence.

The 1994 crime law was certainly meant to increase incarceration in an attempt to crack down on crime, but its implementation doesn’t appear to have done much in that area. And while the law had many provisions that are now considered highly controversial, some portions, including the Violence Against Women Act and the assault weapons ban, are fairly popular among Democrats.

But with Biden’s criminal justice record coming under scrutiny as he runs for president, it’s the mass incarceration provisions that are drawing particular attention as a key example of how Biden helped fuel the exact same policies that criminal justice reformers are trying to reverse. And while Biden has released sweeping criminal justice reform plans that aim to, in some sense, undo the damage of policies he previously championed, Biden’s history has led to skepticism among some progressives and reformers.

The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, now known as the 1994 crime law, was the result of years of work by Biden, who oversaw the Senate Judiciary Committee at the time, and other Democrats. It was an attempt to address a big issue in America at the time: Crime, particularly violent crime, had been rising for decades, starting in the 1960s but continuing, on and off, through the 1990s (in part due to the crack cocaine epidemic).

At the same time, the law included several measures that would be far less controversial among Democrats today. The Violence Against Women Act provided more resources to crack down on domestic violence and rape. A provision helped fund background checks for guns. The law encouraged states to back drug courts, which attempt to divert drug offenders from prison into treatment, and also helped fund some addiction treatment.

All of this was an old-school attempt to attract votes from lawmakers who otherwise might be skeptical, and it succeeded at winning over some Democrats. Bernie Sanders, for one, criticized an earlier version of the bill, written in 1991 but never passed, for supporting mass incarceration, quipping, “What do we have to do, put half the country behind bars?” But he voted for the 1994 law, explaining at the time, “I have a number of serious problems with the crime bill, but one part of it that I vigorously support is the Violence Against Women Act.”

Asked about Biden’s support for the law, the Biden campaign pointed to provisions like the Violence Against Women Act, the 10-year assault weapons ban, firearm background check funding, money for police, support for addiction treatment, and a “safety valve” that let a limited number of low-level first-time drug offenders avoid mandatory minimum sentences. They also cited some of his past criticisms of punitive sentences, including the three-strikes measure, and pointed out that a Republican-controlled Congress later cut funding drastically for drug courts.

In a 2020 context, the 1994 law has been criticized for contributing to mass incarceration. This goes back to at least 2016, when activists and writers like Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, cited the law to criticize Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.

This is a bit of a dodge as to whether the bill intended to increase incarceration, but Biden is generally correct that the bill, despite its intentions, didn’t actually succeed at expanding incarceration much.

Beyond the changes to hike federal penalties, the 1994 law attempted to encourage states to adopt harsher criminal justice policies. It provided money for states to build prisons and adopt “truth in sentencing” laws that increase prison sentences by requiring inmates to serve out at least 85 percent of their prison sentences without an early release. It’s here where the law could have had most its impact on incarceration — since, as Biden indicated, nearly 88 percent of inmates are held at the state level.

At the time of our review, based upon determinations made by DOJ, 27 states had TIS laws that met the requirements for receiving federal TIS grants. For each of these 27 states, we contacted state officials to determine whether the availability of such grants was a factor in the respective state’s decision to enact a TIS law. Based on the responses to our telephone survey, the states can be grouped into three categories—TIS grants not a factor (12 states), TIS grants a partial factor (11 states), and TIS grants a key factor (4 states).

According to Ohio officials, the state passed its TIS law in 1995, which is later than the enactment date of the 1994 Crime Act. However, the officials told us the state law was based on a July 1993 report by the Ohio Sentencing Commission. Thus, according to the state officials, the availability of federal grants did not influence the state’s decision to pass TIS legislation. Rather, according to Ohio officials, a widespread concern about early release of violent crime offenders was a major factor in the state’s decision to pass TIS legislation.

A more recent report, published by the National Institute of Justice in 2002, produced similar findings: “Overall, Federal TIS grants were associated with relatively few State TIS reforms. There was relatively little reform activity after the 1994 enactment of the Federal TIS grant program, as many States had already adopted some form of TIS by that time.”

That’s reflected in the statistics, which show that incarceration rates were climbing rapidly before the 1994 crime law and actually started leveling off a few years after.

In this way, a clear reading of the 1994 law’s actual effects is very relevant not just to Biden’s politics, but to criminal justice reformers’ efforts to undo mass incarceration.

Comprehensive Control Act: This 1984 law, spearheaded by Biden and Sen. Strom Thurmond (R-SC), expanded federal drug trafficking penalties and civil asset forfeiture, which allows police to seize and absorb someone’s property — whether cash, cars, guns, or something else — without proving the person is guilty of a crime.

Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986: This law, sponsored and partly written by Biden, ratcheted up penalties for drug crimes. It also created a big sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine; even though the drugs are pharmacologically similar, the law made it so someone would need to possess 100 times the amount of powder cocaine to be eligible for the same mandatory minimum sentence for crack. Since crack is more commonly used by Black Americans, this sentencing disparity helped fuel big racial disparities in incarceration.

Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988: This law, co-sponsored by Biden, increased prison sentences for drug possession, enhanced penalties for transporting drugs, and established the Office of National Drug Control Policy, which coordinates and leads federal anti-drug efforts.

Biden is also now running against Trump, who still proudly calls himself “tough on crime” and continues to push for tougher prison sentences, more aggressive police tactics, and wider use of the death penalty. While Trump signed criminal justice reform in the First Step Act, it appeared to be a political favor and a weak attempt to win over minority voters, not a genuine change of heart. And Trump’s administration has undermined the law, with federal prosecutors actively resisting the release of some inmates who qualify under the First Step Act. If the choice is between Biden and Trump, Biden is clearly better for reform.

Given that the central progressive claim is that these policies are racist and, based on the research, ineffective for fighting crime in the first place, any potential for backsliding in this area once it becomes politically convenient is very alarming.

8613371530291

8613371530291