seizing wire rope ends price

Proper seizing and cutting operations are not difficult to perform, and they ensure that the wire rope will meet the user’s performance expectations. Proper seizings must be applied on both sides of the place where the cut is to be made. In a wire rope, carelessly or inadequately seized ends may become distorted and flattened, and the strands may loosen. Subsequently, when the rope is operated, there may be an uneven distribution of loads to the strands; a condition that will significantly shorten the life of the rope.

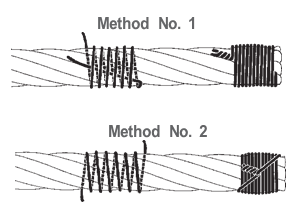

Either of the following seizing methods is acceptable. Method No. 1 is usually used on wire ropes over one inch in diameter. Method No. 2 applies to ropes one inch and under.

Method No. 1: Place one end of the seizing wire in the valley between two strands. Then turn its long end at right angles to the rope and closely and tightly wind the wire back over itself and the rope until the proper length of seizing has been applied. Twist the two ends of the wire together, and by alternately pulling and twisting, draw the seizing tight.

The Seizing Wire. The seizing wire should be soft or annealed wire or strand. Seizing wire diameter and the length of the seize will depend on the diameter of the wire rope. The length of the seizing should never be less than the diameter of the rope being seized.

Proper end seizing while cutting and installing, particularly on rotation-resistant ropes, is critical. Failure to adhere to simple precautionary measures may cause core slippage and loose strands, resulting in serious rope damage. Refer to the table below ("Suggested Seizing Wire Diameters") for established guidelines. If core protrusion occurs beyond the outer strands, or core retraction within the outer strands, cut the rope flush to allow for proper seizing of both the core and outer strands.

(a) The seizing shall be done with annealed iron wire, provided that other methods of seizing that give the same protection from loss of rope lay are permitted. Where iron wire is used for seizing, the length of each seizing shall be not less than the diameter of the rope.

(b) For nonpreformed rope, three seizings shall be made at each side of the cut in the rope. The first seizing shall be close to the cut end of the rope, and the second seizing shall be spaced back from the first the length of the end of the rope to be turned in. The third seizing shall be at a distance from the second equal to the length of the tapered portion of the socket.

(c) For preformed rope, one seizing shall be made at each side of the cut in the rope. The seizing shall be at a distance from the end of the rope equal to the length of the tapered portion of the socket plus the length of the portion of the rope to be turned in.

THERE are four varieties of rope in the United States naval service: that made of the fibres of the hemp plant; the Manilla rope, made of the fibres of a species of the wild banana; hide rope, made of strips of green hide, and wire rope.

In some countries, ropes made of horse hair, of the fibrous husk of the cocoanut, called coir-rope, and of tough grasses, are quite common. In our own country, rope has been made from the flax and cotton plants. The metals have also been put in requisition, copper-wire rope being used for particular purposes, principally for lightning conductors, and iron and steel wire are in general use for standing rigging; steel wire being some fifty per cent. stronger than iron wire of the same size.

Of the many vegetable substances that are adapted to rope-making, the best is hemp-hemp-rope possessing in a remarkable degree the essential qualities of flexibility and tenacity.

Hemp in its transit from its native fields to the ropewalk passes through the operations of dew-rotting, scotching and hackling. In the first process water dissolves the glutinous matter that binds the fibrous portion to the woody core, thus partly setting the fibres free; scotching breaks the stalk and separates it still further from the fibre, and hackling consists in combing out the hemp to separate the long and superior fibres from the short and indifferent ones or tow.

The hemp of commerce is put up in bundles of about 200 lbs. each. If good, it will be found to possess a long, thin fibre, smooth and glossy on the surface, and of a yellowish green color; free from "spills" or small pieces of the woody substance; possessing the requisite properties of strength and toughness, and inodorous.

Russian and Italian hemp are considered the best, for the generality of purposes. Rope made from the best quality of Russian hemp, is more extensively used in the navy than any other kind.

The size of Rope is denoted by its circumference, and the length is measured by the fathom. The cordage allowed in the equipment of a man-of-war ranges from 1 1/4 (15-thread) to 10 inches inclusive.

Varieties of Rope. In rope-making the general rule is to spin the yarn from right over to left. All rope yarns are therefore right-handed. The strand, or ready, formed by a combination of such yarns, becomes left-handed. Three of these strands being twisted together form a right-handed rope, known as plain-laid rope. Fig. 14, Plate 7.

White Rope. Hemp rope, when plain-laid and not tarred in laying-up, is called white rope, and is the strongest hemp cordage. It should not be confounded with Manilla. It is used for log-lines and signal halliards. The latter are also made of yarns of untarred hemp, plaited by machinery to avoid the kinking common to new rope of the ordinary make. This is called "plaited stuff," or "signal halliard stuff."

The tarred plain-laid ranks next in point of strength, and is in more general use than any other. The lighter kinds of standing rigging, much of the running rigging, and many purchase falls are made of this kind of rope.

Cable-laid or Hawser-laid Rope, Fig. 15, is left-handed rope of nine strands, and is so made to render it impervious to water, but the additional twist necessary to lay it up seems to detract from the strength of the fibre, the strength of plain-laid being to that of cable-laid as 8.7 to 6; besides this, it stretches considerably under strain.

Shroud-laid. Rope, Fig. 16, Plate 7, is formed by adding another strand to the plain-laid rope. But the four spirals of strands leave a hollow in the centre, which, if unfilled, would, on the application of strain, permit the strands to sink in, and detract greatly from the rope"s strength, by an unequal distribution of strain. The four strands are, therefore, laid up around a heart, a small rope, made soft and elastic, and about one-third the size of the strands.

Experiments show that four-stranded rope, when under 5 inches, is weaker than three-stranded of the same size; but from 5 to 8 inches, the difference in strength of the two kinds is trifling, while all above 8 inches is considered to be equal to plain-laid when the rope is well made.

Tapered Rope is used where much strain is brought on only one end. That part which bears the strain is full-sized, tapering off to the hauling part, which is light and pliable. Fore and main tacks and sheets are made of tapered rope.

Twice-laid Rope is made from second-hand yarns. This rope may be readily known by the different shades of color of the yarns, but it is often difficult to determine, by mere inspection, whether it is relaid from what was good rope, and, consequently, still good, or made up from junk or condemned rigging, and worthless. Twice-laid rope is only met with on board ship when necessity has compelled its purchase on foreign stations.

Manilla Rope seems to be better adapted to certain purposes on board ship than hemp, being more pliable, buoyant, causing less friction, and not so easily affected by moisture. It is used for hawsers, tow-lines, and for light-running rigging and gun-tackle falls. Manilla is now less used in the navy than formerly. The Book of Allowances states that the cheap first cost of Manilla as compared with hemp is more than compensated by the greater market value of the hemp when worn-out. This statement is not correct if applied to the current relative values of hemp and Manilla junk in this country.

Hide Rope is made of strips cut by machinery from green hides. Formerly used for topsail tyes, and for tailing on to such ropes as are exposed to much chafe in some particular part, as topsail sheets, etc., it is now allowed only for wheel ropes. Its strength is about one-third that of hemp.

Hide rope requires care to keep it in good order, and should not be exposed to the weather unnecessarily. It should be given a lick of thin tar (Swedish preferred)

Avoid serving the splices of hide rope. When spare wheel ropes are stowed away they should be well oiled and headed up in a barrel to preserve them from rats and mice.

Wire Rope for general use in the navy is made from one quarter to seven inches, inclusive, in circumference, those being the maximum and minimum sizes likely to be needed.

When first introduced, it was thought that great difficulty would be found in manipulating wire rigging, but our best riggers cut, fit and splice it as readily as they do hemp rigging.

In its less bulk and cost, wire rope has decided advantages over hemp for the standing rigging. of ships, and now all vessels of the navy are provided with standing rigging of wire.

Besides the great advantage that wire rigging possesses of not being affected by the heat and sparks from the smokestack, its durability is at least three or four times that of common rope, and, when once completely set, does not require further pulling up.

In Appendix A will be found a table of comparative dimensions of chain cables, hemp, iron and steel rope, with breaking strains and weights per fathom.

Small Stuff is the general term applied to small rope. It is particularized by the number of threads or yarns which it contains, and is further known either as ratline stuff or seizing stuff.

Seizing Stuff, Is of 9, 6, 4 or 2 threads, and is measured by the pound. While all varieties of small stuff may be spoken of as "24, 18, 9, &c., thread stuff," the smaller varieties have also special names, according to their number of threads and the manner of laying up. We have:

Spun-Yarn is also left-handed, and of two, three or four strands. Spun-yarn is always in great demand aboard ship, being used for seizings, service, and a great variety of purposes. In its manufacture, "long tow," as it is termed, or the tow of the first hackling, is hackled again, and laid up loosely, left-handed, and to keep it from opening is well tarred and rubbed down.

For fine seizings and service, hambroline and roundline (right-handed), or marline and housline (left-handed) are the kinds of small stuff selected. For ordinary purposes, spun-yarn is used.

Foxes, used for temporary seizings, making mats, sennit, gaskets, reefing beckets, boat gripes, bending studding sails, &c., are made of two or more yarns, as required, laid up by twisting by hand, and then well rubbed down with a piece of tarred parcelling.

A Spanish Fox is a single yarn twisted up tightly in a direction contrary to its natural lay-that is, left-handed, and rubbed smooth. It makes a neat seizing, and is used for the end seizings of light standing rigging, and for small seizings generally.

Rogue"s Yarn is a single untarred thread, sometimes placed in the centre of the rope, or in the centre of each strand, denoting government manufacture.

Junk is supplied for the purpose of working up into various uses-such as for swabs, spun-yarn, nettle-stuff, lacings, seizings, earings, gaskets, &c.-of all of which the supply, in proper kind, is generally inadequate. Good junk is got out of such material as condemned hawsers-they having been necessarily made of the best stuff, and condemned before being much injured. Old rigging makes bad junk, not being condemned generally until much worn.

Shakings are odds and ends of yarns and small ropes, such as are found in the sweepings of the deck after work. They are collected, put in a bag kept for the purpose, and at certain times served out to the watch to be picked into Oakum, a good supply of which should always be on hand for any calking that may be required, for stuffing jackasses, boat"s fenders, &c.

Use of the Ropermaker"s Winch, Fig. 18, Plate 7. A ship"s winch, which will make very fair 2-inch rope, is about 15 inches in diameter. In the frame, which is double, are placed five hooks-the three upper ones for general use, the fourth for four-stranded rope, and the centre one for hardening up large rope after it has been laid up by the upper ones (the latter not being sufficiently strong for the purpose). The shanks of the hooks, between the two parts of the frame, are inserted in cogged barrels, which are turned by the wheel, one revolution of which gives nine to the hooks-any one of which can be thrown out of gear by hauling it back close to the after part of the frame.

The top, Fig. 17 (b), is a conical piece of wood, scored on the outside for the reception of the strands. Its use is to keep the strands separate between it and the winch, and to regulate the amount of twist in the rope behind it, by being moved along either slowly or rapidly. When four-stranded rope is required, a hole is bored through the centre, as a lead for the heart.

A length of junk being brought on deck, you proceed to unlay it by attaching the strands to separate hooks, and the loper to the other end-one hand holding back on it, and then heaving back-two hands following the rope down to separate the ends.

Spun-Yarn is made by hooking all the yarns that compose it (according to the size required) upon one hook. You then heave round, the reverse way to the lay of the yarns (which in ordinary rope are all right-handed) until there is plenty of back turn in them, holding on the ends by hand; then rub down and make it up.

reverse way; the yarns are thus hove up the contrary way to what they were originally, to soften them; for when drawn out of rope, they are usually hard and angular; and would not lie square, or bear an equal strain, if laid up in that condition. When thus relaid, the ends are knotted together, the loper hooked on-one hand holding on to it, the top put in, the winch hove round the same way as at first, and the top moved along towards the winch. When up to it, the top is taken out, the yarns unhooked, and hitched to a single hook, then the winch hove round the opposite way to what you have just been heaving it, to harden the stuff up; rub down and make up.

Six (or nine) Thread Stuff: Put two (or three) yarns on three separate hooks; hold on the end by hand, keeping each of the three lengths separate, and heave round a reverse turn, as with spun-yarn. When sufficiently hove up, knot the ends together, hook on the loper, put in the top, and proceed as with nettle-stuff.

General Remarks on Rope. The strength of a rope-yarn of medium size is equal to 100 lbs., but the measure of strength of a given rope is not, as might naturally be supposed, 100 lbs. multiplied by the number of yarns contained in the rope. The twist given to the yarn, after certain limits, diminishes its strength, as already stated, and with the best machinery it is scarcely possible that each yarn of the tope should bear its proper proportion of strain. The difference in the average strength of a yarn differs with the size of the rope. Thus, in a 12-inch rope, the average strength of each yarn is equal to 76 lbs., whereas, in a rope of half an inch, it is 104 lbs.

Experiment has shown that by applying a constant, or even frequent, strain equal to half its strength, the rope will eventually break. This seems to be particularly the case with cable-laid rope, which is the weakest of all.

It has been ascertained that a good selvagee, carefully made with the same number and description of yarns, as the common three-stranded plain-laid rope, possesses about the same degree of strength.

It has been shown by experiment, that where a span is so placed as to form an angle less than 30 degrees, the strength of the two parts of the rope or chain of which it is composed, is less than the strength which one such part would have if placed in a direct line with the strain.

the direction pursued by the hands of a watch; the left-handed ropes, against the sun. An exception to this rule is in the hemp cables and hawsers, which are left-handed and are coiled away with the sun.

Rope contracts very considerably by wetting it. Advantage may be, and often is, taken of this, by wetting lashings, which are required to be very taut and solid, and are not permanent, as the lashing of a garland on a lower mast for taking it in or getting it out. For the same reason in rainy weather, braces, halliards, sheets, clew-lines, and other rigging requiring it, should be slacked up to save an unnecessary strain on the rope, and avoid the risk of springing a yard or carrying something away.

Running rigging has nothing to protect it from the effects of the weather, excepting, in hemp, the tar taken up in the process of manufacture, and after being wet the air should be allowed to circulate through it freely. Rope should never be stowed away until thoroughly dry.

Running rigging, when not in actual use, should be kept neatly coiled down near the pin to which it belays, taking care always to capsize the coil that the running part may be on top, so that it may run clear. In port, during good weather, the rigging may be coiled down in flemish coils, that is, perfectly flat, as soon as the decks are dry enough in the morning, and left so until the decks are cleared up at seven bells in the afternoon, when the ends should be run out, the rope coiled down snugly and triced up in readiness for washing decks in the morning.

One rope may be rove by another by putting the two ends together, and worming three yarns or pieces of spun-yarn in the lay for three or four inches on each side, and clove-hitching the ends around the rope, or opening the strands and laying them in. This is always done when reeving new braces by old ones, and with running rigging generally.

Practical Rule for ascertaining the Strength of Rope. The square of half the circumference gives the breaking strain of the weakest plain-laid rope in tons, and is therefore a safe rule.

For ascertaining the Weight of Rope. Three-strand, plain-laid, 25-thread yarn, tarred. Multiply the square of the circumference by the length in fathoms, and divide by 4.24 for the weight in lbs.

A Practical Rule for determining the relative Strength of Chain and Rope. Consider the proportionate strength of chain and rope to be ten to one-using the diameter of the chain and the circumference of the rope. Half-inch chain may, therefore, replace five-inch rope.

To find the size of Rope when rove as a Tackle to Lift a given Weight: Divide the weight to be raised by the number of parts at the movable block to get the strain on a single part, add one-third of this for the increased strain due to friction, and reeve the rope of the corresponding strength.

To find what Number of parts of a parts of a small Rope are equal to a large Rope: Divide the square of the circumference of the larger rope by the square of the circumference of the smaller, and the result will be the number of parts of the smaller equal to one part of the larger.

To Knot a Rope Yarn, Fig 19, Plate 8. Split in halves the two ends of a rope-yarn, scrape them down with a knife, crotch and tie the two opposite ends; jam the tie and trim off the ends.

A Bow-Line Knot, Fig. 26, Plate 8. Take the end of the rope (a), Fig. 24, in the right hand, and the standing part (b) in the left, laying the end over the standing part; with the left hand turn a bight of the standing part over it, Fig. 25; lead the end round the standing part, through the bight again, and it will appear like Fig. 26. The bight turned in the standing part is often called a Cuckold"s Neck.

A Running Bow-Line Knot, Fig. 28, Plate 8. Take the end of a rope, Fig. 27, round the standing part (b) and through the bight (c); make the single bow-line knot upon the part (d), and it is done.

A Bow-Line Knot upon the Bight of a Rope, Fig. 30, Plate 9. Take the bight (a) in one hand, Fig. 29, and the standing parts (b) in the other; throw a kink or Cuckold"s Neck over the bight (a) with the standing parts, the same as for the single knot; take the bight (a) over the large bights (c, c), bringing it up again: it will then be complete, Fig. 30. The best way to sling a man by a bow-line is to shorten up one of the lower bights, using the lower part as a seat and putting the arms through the part next above.

into, as in Fig. 218, Plate 29, is used for heavy pulls, on the ends of rigging luffs, by riggers. Fig. 79, Plate 14, shows an ordinary bow-line knot formed over a ring-bolt to make a temporary stopper. Shove the bight through the ring-bolt, take a half hitch with the short end over the bight, then pass the short end through the bight. A handy knot when you wish to use a short end of a long coil.

A Wall Knot. Unlay the end of a rope, Fig. 32, Plate 9, and with the strand (1) form a bight, holding it down on the side of the rope at (2); pass the end of the next (3) round the strand (1); the end of the strand (4) round the strand (3) and through the bight which was made at first by the strand (1); haul them rather taut, and the knot will then appear like Fig. 33.

To Crown this knot, Fig. 35, Plate 9. Lay one of the ends over the top of the knot, Fig. 34, which call the first (a); lay the second (b) over it, and the third (c) over (b), and through the bight of (a); haul them taut, and the knot with the crown will appear like Fig. 35, which is drawn open, in order to render it more clear. This is called a Single Wall, and Single Crown.

To Double-Wall this knot, Fig. 36, Plate 10. Take one of the ends of the single crown, suppose the end (b), bring it underneath the part of the first walling next to it, and push it up through the same bight (d); perform this operation with the other strands, pushing them up through two bights, and the knot will appear like Fig. 36, having a Double Wall and Single Crown.

To Double-Crown the same knot, Fig. 37, Plate 10. Lay the strands by the sides of those in the single crown, pushing them through the same bights in the single crown, and down through the double walling; it will then be like Fig. 37, viz. single walled, single crowned, double walled, and double crowned. The first walling must always be made against the lay of the rope: the parts will then lie fair for the double crown. The ends are scraped down, tapered, marled, and served with spun yarn. This knot is often used for the ends of man-ropes, and hence frequently called a Man-rope Knot.

Matthew Walker"s Knot, Fig. 39, Plate 10. This knot is made by separating the strands of a rope, Fig. 38, taking the end (1) round the rope, and through its own bight, the end (2) underneath through the bight of the first, and through its own bight, and the end (3) underneath, through the bights of the strands (1 and 2), and through its own bight. Haul them taut, and they form the knot, Fig. 39. The ends are cut off. This is a handsome knot for the end of a laniard, and is generally used for that purpose.

own part, Fig. 40. Render the parts through, jam taut, lay up and whip the end, Fig. 41. This knot is used for bucket ropes, &c. It should have a leather washer around its neck when exposed to chafe.

A Single Diamond Knot, Fig. 43, Plate 11. Unlay the end of a plain-laid rope for a considerable length, Fig. 42, and with the strands form three bights down its side, holding them fast. Put the end of strand (1) over strand (2), and through the bight of strand (3), as in the figure; then put the strand (2) over strand (3), and through the bight formed by the strand (1), and the end of (3) over (1), and through the bight of (2). Haul these taut, lay the rope up again, and the knot will appear like Fig. 43. This knot is used for the side ropes, jib guys, bell ropes, &c.

A Double Diamond Knot, for the same purpose, Fig. 44, Plate 11. With the strands opened out again, follow the lead of the single knot through two single bights, the ends coming out at the top of the knot, and lead the last strand through two double bights. Lay the rope up again as before, to where the next knot is to be made, and it will appear like Fig. 44.

A Sprit-Sail Sheet Knot, Fig. 47, Plate 11. Unlay two ends of a rope, and place the two parts which are unlaid, together, Fig. 45. Make a bight with the strand (1). Wall the six strands together, against the lay of the rope (which being plain-laid must be done from the right hand to the left), exactly in the same manner that the single walling was made with three; putting the second over the first, the third over the second, the fourth over the third, the fifth over the fourth, the sixth over the fifth, and through the bight which was made by the first; haul them rather taut, and the single walling will appear like Fig. 46; then haul taut. It must be then crowned, Fig. 47, by taking the two strands which lie most conveniently (5 and 2) across the top of the walling, passing the other strands (1, 3, 4, 6) alternately over, and under those two, hauling them taut; the crown will be exactly similar to the figure. It may be then double walled, by passing the strands (2, 1, 6, &c.) under the wallings on the left of them and through the same bights, when the ends will come up for the second crowning, which is done by following the lead of the single crown, and pushing the ends down through the walling, as before, with three strands. This knot, when double-walled, and crowned, is often used as a stopper knot, in the Merchant Service.

A Stopper for a Stranded Foot or a Leech Rope, Fig. 48, Plate 12. This is made by double walling, without crowning, a three-stranded rope, against the lay, and stopping the ends together, as in the figure. The ends, if very short, are whipped without being stopped.

A stopper knot on the end of a deck stopper is made as in Fig. 49, by a single crown and single wall. The ends are whipped singly and cut off. A deck stopper has a laniard spliced around the neck of the knot, and a hook and thimble spliced in the other. When made of wire rope, a deck stopper is fitted as in Fig. 50, where an iron toggle is spliced. into the end of the stopper in place of the knot.

A Shroud Knot. Unlay the ends of two ropes, Fig. 51, placing them one within the other, drawing them close as for splicing; then single-wall each set of ends-those of one rope, against the lay (i.e. from left to right if the rope be cable-laid, as in the figure), round the standing part of the other. The ends are then opened out, tapered, marled down, and served with spun-yarn. This knot is used when a shroud is either shot or carried away. Fig. 54 and Fig. 55.

A French Shroud Knot. Place the ends of two ropes as before, Fig. 51, drawing them close. Laying the ends on one side back upon their own part, single-wall the remaining ends around the bights of the other three and the standing part, and it will appear as in Fig. 52. When hauled taut, it appears as in Fig. 53. The ends are tapered, &c., as before. This knot is as secure as the other, and much neater.

Hitching a Rope, Fig. 56, Plate 12, is performed. thus: Pass the end of a rope (b) round the standing part; bring it up through the bight, and seize it to the standing part at (d). This is called a Half-hitch. Two of these, one above the other, Fig. 57, are called Two Half-hitches or a Clove-hitch. Fig. 58 represents a half-hitch around a spar; Fig. 59, Plate 13, a clove-hitch, with a ratline around a shroud.

A Timber-Hitch, Fig. 61, Plate 13. Take the end part of a rope (a) round a spar or timber-head, lead it under and over the standing part (b), pass several turns round its own part (c), and it is done, Fig. 60; when taut it appears as Fig. 61.

A Cat"s Paw, for the same purpose, Fig. 70, Plate 13. Lay the end of a rope (a), Fig. 68, over the standing part (b), forming the bight (e), take the side of the bight (c) in the right hand, and the side (d) in the left, turn them over from you three times, and there will be a bight in each hand (c d), Fig. 69. Through these put the hook of a tackle, Fig. 70.

A Rolling Hitch, Fig. 73, Plate 14. With the end of a rope (a), Fig. 72, take a half-hitch round the standing part (b), take another turn through the same bight, jamming it between the parts of the hitch; when hauled taut, it will appear like Fig. 73. The end may be taken round the standing part, or stopped to it. It is thus a tail-jigger is clapped on a rope, or fall, to augment the purchase. This is a good hitch for a stopper, as it will not slip, and is in very general use. Fig. 74, Plate 13, shows how a stopper is passed, one of the hitches being omitted.

Hitching the End of a Rope. Trim the end off with a knife to the shape of a cone then, with a sail-needle and twine, stitch it around with a loop-stitch, first taking a few round turns with the twine. When finished it will resemble Fig. 80, Plate 14. All running rigging have the ends hitched to prevent unlaying, as in the figure, instead of the ordinary whipping. All the gun-tackle falls should have their ends hitched, as it is neater and better than the ordinary whipping.

three ends. With two ends,-after seizing or hitching the ends you are not working on to the ring-bolt, you commence by taking a left-handed hitch, Fig. 82, with one of the tails, keeping the cross on the centre of the bolt, which brings the end out to the right; you then double this end back over its own part to the left, bring up the other tail over this, take a hitch as with the first, double it back, bring up the first end, and so go on, taking alternate hitches with each, and bringing the end out to the right with each hitch.

With three ends, you begin by taking a left-handed hitch with the first leg, a right-handed hitch with the second, Fig. 83, then a left-handed with third, right-handed with first,-left, second,-right, third,-and so on, each hitch being passed in the opposite way to the preceding one-two ends and one end alternately lying on each side. The ends are finished off by scraping them down and either passing a whipping or working a Turk"s head round them. When finished: it has the appearance shown in Fig. 81.

A Sheet Bend or Single Bend, Fig. 85, Plate 15. Pass the end of a rope (a) through the bight of another rope (b), then round both parts of the rope (c d), and down through its own bight. It is sometimes called also a Becket-bend, sometimes a Weaver"s Hitch.

A Fisherman"s Bend, Fig. 88, Plate 15. With the end part of a rope take two turns (c) round a spar; a half-hitch round the standing part (b), and under the turns (c); then another half-hitch round the standing part (b). This is sometimes used for bending the studding-sail halliards to the yard, but more frequently for bending a hawser to the ring of an anchor, in which case the end should be stopped down with spun-yarn, Fig. 89.

Hawsers are sometimes bent together thus, Fig. 93, Plate 15; the hawser has a half-hitch cast on it, a throat seizing clapped on the standing part (b) and a round one at (a). Another hawser is rove through the bight of this, hitched in the same manner, and seized to the standing part (d, e).

And frequently the ends of two ropes (a, c), Fig. 94, Plate. 15, are laid together; a throat seizing is clapped on at (e), the end (a) is turned back upon the standing part (b), and the standing part (d) brought back to (c); another throat seizing is put on each, as at (1), Fig. 95, and a round seizing near the end at (g); the same security is placed on the other side.

The clinch is made like Fig. 97, Plate 16; the end of a bridle or leech line, for example, is rove through the cringle (f), taken round the standing part (e), forming a circle; two round seizings (d) are then clapped on. The clinch on any rope is always made less than the cringle, &c., through which the rope is rove.

To Bend a Hemp Cable, use an inside clinch. The end of the cable (a), Fig. 100, Plate 16, is taken over and under the bight (b), forming the shape of the clinch, which must not be larger than the ring of the anchor (d). The seizings (c), which are called the BENDS, are then clapped on and crossed.

Ropes are joined together, for different purposes, by uniting their strands in particular forms, which is termed Splicing. A splice is made by opening, and separating the strands of a rope"s end, and thrusting them through the others which are not unlaid. The instruments used for this

are Fids, Marling-Spikes, and Prickers. Ropes reeving through blocks are joined by a long splice, otherwise a short splice is used. The splice is weaker than the main part of the rope by about one-eighth.

A Fid is made according to the size of the rope it is meant to open and is tapered gradually from one end to the other, Fig. 103, Plate 16. It is commonly made of hard wood, such as Brazil, Lignum-vitae, &c., and sometimes of iron when of the latter, it has an eye in the upper end, like Fig. 104.

An Eye-Splice, Fig. 106, Plate 16, is made by opening the end of a rope, and laying the strands (e, f, g) at any distance upon the standing part forming the Collar or Eye (a). The end (h), Fig. 107, is pushed through the strand next to it (having previously opened it with a marling-spike); the end (i) is taken over the same strand, and through the second, Fig. 108; and the end (k) through the third, on the other side, Fig. 110. After sticking the ends once, one-half of the yarns may be cut away from the under part of the strands, and the remainder stuck again, in order to taper the splice and make it neater. In a four-stranded rope, the left-hand end lies under two strands, Fig. 111.

An Eye-Splice in a Wire Rope. Wire requires more end for splicing than hemp. Stick the whole strand once, once two-thirds, and once one-third of a strand, which will make a good taper; then set it up and stretch it well, break off the yarns close to the rope by working them backwards and forwards quickly, two or three times; then parcel and serve over with spun yarn. After sticking the ends once, clap on a good stop around all to keep the parts close together while sticking the second time, and so on.

with the other ends, by leading them over the first and next to them, and through under the second, on both sides; the splice will then appear like Fig. 113; but in order to render it more secure, the work must be repeated; leading the ends over the third and through the fourth; or the ends may be untwisted, scraped down with a knife, tapered, marled, and served over with spun-yarn.

When there is to be no service used, the ends should be stuck twice each way, otherwise once and a half is sufficient. In anchor straps, and heavy straps generally, the ends are stuck twice and not trimmed off but whipped.

In whipping the strands they should be split and one part of each whipped, or seized, with one part of another so as to enclose a strand of the rope on each side of which they appear.

The Long Splice, Fig. 115, Plate 17. To make this splice, unlay the ends of two ropes to a convenient distance, and place them one within the other, as for the short splice; unlay one strand for a considerable length, and fill up the intervals which it leaves with the opposite strand next to it. For example, the strand (1) being unlaid for a particular length, is followed in the space which it leaves by the strand (2). The strand (3) being untwisted to the left hand, is followed by the strand. (4) in the same manner. The two middle strands, (5 and 6), Fig. C, are split; an over-hand knot is cast on the two opposite halves, and the ends led over the next strand and through the second, as the whole strands were in the short splice; the other two halves are cut off. When the strand (2) is laid up to the strand (1), they are divided, knotted, and the ends cut off in the same manner; and so with 3 and 4. This splice is used for lengthening a rope which reeves through a block, or sheave-hole, the shape of it being scarcely altered. After splicing, the ends should not be trimmed off until after the splice has been subjected to a good strain.

The following is somewhat neater. Fig. 117, Plate 18. Unlay the ends alike, and marry them together; unlay a strand on each side, and lay the strand of the Other end, that is opposite to it, up in the lay that it comes out of, making both equidistant from the centre pair of strands, which you do not touch. Twist each pair up as you have done with them, to keep them in their places, and grease the strands. For a large rope, such as the fore brace, instead of knotting the strands, merely lay them alongside each other in the score of the rope, then put the ends in once, a half, and a quarter, and back it with the remaining quarter of a strand to taper it off. In splicing, instead of laying a strand over one, and under the next, you back it by putting the strand in left-handed, under the strand you

A Cut or Bight Splice, Fig. 120, Plate 18. Cut a rope in two, and, according to the size of the collar or eye you mean to form, lay the end of one rope upon the standing part of the other, and push the ends through, between the strands, in the same manner as for the eye-splice, shown in Fig. 106, Plate 16. This forms a collar or eye (u) in the bight of the rope. The yarns left out from the strands should be scraped, marled down and served over, when neatness is required.

A Horse-Shoe Splice, or span-splice, Fig. 121, is formed by splicing the two ends of a piece of rope into each side of the bight of another rope, where an eye is to be formed. The length of rope used is one-third the length of the eye required, with twice the round of the rope on each end, in addition, for splicing.

To Long-Splice a Three and a Four-Stranded Rope Together. Unlay the ends of the two ropes to a sufficient length and crotch them; unlay one strand of the three-s branded, and fill the space with a strand of the four-stranded rope; then unlay a strand of the four and fill up from the three-stranded rope; there remains two strands of the four, and one of the three; divide the single strand by taking out one-third, with which knot to one of the remaining pair, then unlay the other one, and fill up with the remaining two-thirds; knot and stick once, stretch well, and trim off.

Lengthening a Rope with an Additional Strand, Fig. 122, Plate 18. Cut a strand at 1, unlay until you come to 2, and cut another strand; unlay both to 3 (equal to the distance from 1 to 2, or thereabouts), and there cut the last strand separate the parts, and they will appear as in Fig. 122, B. Measure off the increased length required from 1, mark it (a), and bring the end of the left-hand piece (b) down to (a), and lay it in. The second strand, at 2, must have been cut sufficiently far from (a) to allow end enough for knotting and laying in. Twist the ends (c and b) up together ready for knotting, on finishing the splice, and (d and e) in the same manner for the present; the splice will then have the appearance represented in Fig. 122, c. Cut a piece of rope, and unlay a strand sufficiently long to fill in the vacant lay between (f and g), and to knot with the ends (f, g); lay the strand

in, and finish off as with an ordinary long-splice, from which it will only differ in appearance by its having four breaks in the rope instead of three. In putting in the long strand, care must be taken to follow the lay along correctly, or it will not tally with the ends (f, g), with which it knots.

If it is required to give a sail more spread by inserting a cloth, the head and foot rope must be lengthened in this way. For all sizes of rope, take eight times the round for splicing, in addition to what is wanted to lengthen the rope. To lengthen two feet, cut the strands three feet apart; and the additional strand must be over nine feet long.

To Shorten a Rope in the Centre. Proceed precisely as in the previous case but, instead of separating strand (b) from 1, bringing it down to (a), take it up on 1 as far as you require to reduce the rope. No additional strand is used, so knot (b, f), (d, g), and (e, c); finish off the ends, and in appearance it differs in no way from the common long-splice.

To Splice a Rope around a Thimble. Whip the rope at twice and a half its circumference from the end. The length to go round the thimble should be once the round of the thimble, and once the round of the rope, from the whipping to where the first strand is to be struck. If the splice is not to be served, whip the ends of the strands, to prevent them from opening out into yarns, and stick them twice, whole strand. If to be served, after one half of each strand is put through, it is cut off, and the other half is opened out, wormed along the lay, and marled down. Parcel the thimble.

A Sailmaker"s Splice is used when ropes of different sizes are to be joined neatly, and they require tapering, that the change may be gradual; as in splicing the leech and head rope of a topsail.

Unlay enough of the small rope to stick the ends once and a half, but of the larger one, unlay for a considerable distance, according to the relative disproportion of the ropes, and the degree of tapering required; crotch, as for a common splice. Take a strand of the large rope, cut away about one-fourth from the under part, and put it, left-handed, through the corresponding strands of the small rope; cut away a few more yarns, and pass it again, back-handed, round the same strand of the small rope; and so proceed, working with the same strand of the large rope round and round the same strand of the small one, cutting away gradually till it is reduced to nothing. Then, one at a time, put the other large strands through in a similar manner, cutting away more or less of the third strand, as may be necessary to give roundness to the splice. Finally, slue round and splice the small strands into the large rope, as in a common short splice, tapering the ends.

A Mariner"s Splice is a long splice in a cable-laid rope. Proceed as in a long splice, when, instead of sticking the strands, they in turn are long-spliced; get it on a stretch with luffs, and trim off the ends. This splice is not very often used, for it can be done only with old soft hawsers, which should rather be shroud-knotted, the ends marled down and served over.

Splicing a Hawser, Work a long splice, as with a plain-laid rope, but, instead of knotting the strands, unlay them, marry them together, and tuck them in under the strand that you would reeve them through if you had knotted them in the usual manner; under this first strand of the hawser put all three parts of the strand; under the next, two only; then one, and, lastly, back this one.

To Splice a Small Rope to a Chain, Fig. 123, Plate 18. Unlay the end and reeve two of the strands through the end link; unlay the third strand (3) some distance back, following it up as in a long splice with one of the other strands (2); half-knot and stick as in a splice; the remaining end. (1), one of the two rove through the link, is stuck where it is, near the link, as in an eye-splice. This is a very neat and strong splice, and is used for tailing rope to chain topsail sheets; for the standing part of a fall where neatness is required, &c.

A Ropemaker"s Eye is used for forming the collars of stays. A four-stranded stay is unlaid, two strands each way; then each half is doubled back, and laid up with its own part. At the fork, four strands are worked in as in splicing, tapering off by thinning the strands each time they are stuck. The eyes and fork are then wormed and served over. If, instead of laying back both strands to the crotch, but one is so treated, while the other is opened out and used for worming, then each lay will be three-stranded, and look much neater.

If the rope is three-stranded, the eye may be formed in the same way. Unlay the rope, say seven times its own circumference, marl two strands together, tar, parcel and form the eye, putting in a thimble or not, as required; unlay the third strand, following it up by one of the strands that formed the eye, to a distance of about eighteen inches; cross the ends and stick, as in a long splice. The other strand that formed the eye is divided into three equal parts, a portion of each is put in the lays of the rope for worming, and the remainder is tapered, marled down and served over with spun-yarn. This, too, may be termed a ropemaker"s eye. It is strong enough to break the rope.

An Artificial or Spindle Eye, Fig. 126, Plate 19, sometimes, though improperly, called a Flemish eye. Put a whipping on the rope at three and a half times its circumference from the end, which unlay. Take a piece of round wood twice the size of your rope, and lash it to a convenient place, having yarn stops on it to stop the eye after it is formed. With a four-stranded rope, unlay the heart and divide it in two; bring the rope under the spar with two strands, and half the heart on each side; pass the heart over and half knot it on top, heaving the rope close up to the spar with a bolt on each side. The width of the eye should be one-third the round of the rope; take from each strand two yarns for every inch of circumference of rope; if a 10-inch rope take twenty yarns, twist them up, and half-knot them on top of the spar, heave taut and pass them down the lay of the rope for wormings; put a spun-yarn seizing on close to the eye, and another about nine inches below, and put a yarn stop around the ends to keep them in the lay of the rope. Take two-thirds as many yarns from each strand as were used for worming, haul them taut, half-knot them on top, hauling them well taut, and so continue until the yarns are all expended. The yarns must be set well taut alike, or they will not bear an equal strain. Smooth the yarns down and put a stop round all, close underneath the toggle. Half-knot the stops laid lengthwise on the spar, heave them taut with a marling-spike on each side of the eye; form the other half-knot and heave it taut. Marl the eye with two or three yarn spun-yarn; the hitches to be about an inch apart, commencing at the centre of the eye and working both ways; cut the stops as you come to them. Pass a strand round all, close to the spar underneath, and heave taut with marling-spikes, to work the worming taut along the lay; then put on a good spun-yarn seizing. Now tar and parcel the eye and serve it with spun-yarn, fid out, and it is finished, Fig. 127.

Also, the Drawing Splice, Fig. 129, Plate 19, used that the splice might be drawn and the lengths of cable separated. After making a short splice, the ends,

A Grommet, Fig. 131, Plate 19, is made by unlaying a strand of a rope, Fig. 130, placing one part over the other, and with the long end (f) following the lay till it forms the ring, Fig. 131, casting an over-hand knot on the two ends, and, if necessary, splitting and pushing them between the strands, as in the long splice. The test of a well-made grommet is, to throw it on the deck when it should lie perfectly flat. Worn or four-stranded rope makes the best. For grommet straps for yard or block, take three times the round of yard or block and three times the round of the thimble, allowing six times the round of the rope for splicing. The length to marry the strands is, once the round of the block and thimble.

Working a Cringle in a Rope. Unlay a single strand from a rope of the size that the cringle is required to be; begin on the left, and put this strand under two strands of the rope you are working it on; divide it into thirds and haul two-thirds of it through, so that the long leg is from you; lay the two parts up together so as to form sufficient for the round of the cringle, but always with an odd number of turns, ending with the long leg towards you, Fig. 132, Plate 20; stick it from you under two strands; bring it round and work back to the left; put it under two strands towards you, leaving one strand intervening between the place you entered it, then back over one, and down under two, Fig. 133. Now tuck the short end in under the same two strands in the rope that the cringle is already worked through, then over one, and under two; cut the ends off, and serve the cringle over.

If a cringle is to be worked into the leech of a sail, the strand is taken round the rope and through the eyelet-hole in the sail, Fig. 134, Plate 20, and the ends are finished off by taking a hitch round all, and then passed under two, over one, and under two, as before.

Grommet Muzzle-Lashing for Housing Guns. A grommet made of rope double the size of the gun-tackle falls, with two cringles worked into it for the frapping lashing, which will be of stuff half the size of the tackle-falls.

A Spanish Windlass, Fig. 135 (a), Plate 20, is used for heaving two parts of a shroud, or any rope requiring it, together at the nip, before passing the seizing, and for many similar purposes. A strand is laid on the top; the ends are crossed underneath, and brought up on opposite sides, the bights taken round a bar or heaver, laid on the top, a twist is taken in them, and a marling-spike stuck through the bights, and hove upon. See also Fig. 135b.

A Round Seizing, Fig. 138, Plate 20. Splice an eye in the end of a seizing, Fig. 136, and taking the other end round both parts of the rope, reeve it through the eye, pass a couple of turns, haul them taut by hand; then, with a marling-spike-hitch, heave these two turns well taut, by the heaver or marling-spike; pass the rest, and bind them in the same manner, making six, eight, or ten turns, according to the size of the rope; then push the end through the last turn, Fig. 137. Over these, pass five, seven, or nine more (which are termed Riders), always laying one less above than below. These are not to be hove too taut, that those underneath may not be separated. The end is now pushed up through the seizing, and two cross turns, Fig. 138, are taken betwixt the two parts of the rope and round the seizing (leading the end through the last turn), and hove well taut. If the seizing be small stuff, a Wall Knot is cast on the end; but if spun-yarn, an over-hand knot. When this seizing is clapped on the two ends of a rope, it is called an End Seizing. If upon the bight, as in the

A Throat Seizing, Fig. 140, Plate 21, is put on when ropes cross, and is passed with riding turns, but not crossed. A bight is formed, Fig. 139, by laying the end (a) over the standing part (b). The seizing is then clapped on; the end put through the last turn of the riders, and knotted. The end part of the rope, Fig. 140, is turned up and fastened to the standing part, as in the figure, with a round seizing. This is used for turning in dead-eyes, hearts, blocks, or thimbles.

A Round Seizing, second method. Splice an eye in the seizing, pass it under both parts of the rope, and reeve the end through the eye; slack up, lay hold of the upper turn and end part with your left hand, and under turn with your right, and work the seizing round left-handed until enough turns-six, eight, or ten-are wound round, Fig. 141, then reeve the end back between the upper and under turns, and bring it up through the eye; heave each turn taut separately, keeping the eye on the left-hand side, Fig. 142. When you have hauled the end taut through the eye, pass the riding turns round, in the same direction as at first-one in number less than the under turns, and haul hand-taut, Fig. 143. When all on, pass the end down between the last two parts of the upper side of the inner turns, between both parts of the rope, and pass two round turns, crossing all parts of the seizing, Fig. 144; then slue the rope over, and finish off with a reef-knot, Fig. 146, on the under side, or as in Fig. 145.

Racking Seizing, Fig. 147, Plate 21. This seizing is generally made use of in seizing two parts of rope together temporarily, but very securely. When the seizing stuff is fitted with an eye, as in the figure, it is taken around both parts of the rope-the end rove through the eye, and hauled taut, after which it is passed between the two parts of the rope, around the part opposite the eye (of the seizing), back between the ropes, and so on, each full turn, when passed, resembling a figure 8.

Each turn is drawn taut in succession, and the last one is secured by passing the end between the parts of rope inside the last turn, thus jamming it by the hitch formed.

The two lower turns of a throat seizing should be passed as racking turns; and, thus passed, serve well to fill up the open space between the parts of rope, as they are brought together.

A Flat Seizing is commenced the same as a round seizing, but, on the end being rove through the eye, it is finished off at once with a reef-knot without any riding turns.

A Rose Seizing, or Rose Lashing, Figs. 150 and 151, Plate 22, is used when rigging is lashed to yards, etc., such as foot-ropes, &c. It is passed alternately over and under each part of the eye, and the end passed around the crossings instead of cutting it off.

Worming a Rope is filling up the division between the strands (called the lay of the rope) by passing spun-yarn, &c., along them, Fig. 153. This is done in order to strengthen it, for various purposes, and to render its surface smooth for parcelling. After being passed by hand, worming is hove on by a soft strand knotted and taken round the rope; a bolt is then passed through the bights, and the strap twisted up and hove round the rope, which tautens the worming as it proceeds. With very large rope, the worming requires backing* on each side with smaller stuff, in order to fill it up properly. If the rope is not to be served, a seizing, snaked, should be put round the worming at intervals, to keep it in its place, as it is liable to work slack.

Parcelling a Rope, is wrapping strips of old canvas round it, well tarred, with edge overlapping, which prepares it for serving and secures it from being injured by rain-water lodging between the parts of the service when worn, Fig. 156. Parcel with the lay, if service is to be used, otherwise against it.

Service is put on to protect the rope from chafe and the influence of weather. It is clapped on by a wooden mallet, Fig. 154, made for the purpose. The mallet is round at the top, but has a groove cut in the head of it to receive the rope, that the turns of the spun-yarn may be passed

with ease and dispatch. The rope is first bowsed hand-taut by a tackle, then wormed. The end of the spun-yarn for the service is laid upon the rope, and two or three turns passed round the rope and over it (the end), hauling them very taut. The mallet is laid with its groove upon the rope, Fig. 156; a turn of the spun-yarn is taken round the rope and the head of the mallet, close to the last turn which was laid by hand; another is passed in the same manner, and a third also on the fore part of the mallet, leading up round the handle (i), which the rigger holds in his hand. The service is always passed against the lay of the rope, so that as the latter stretches, the tension of the former is not much decreased. A boy holds the ball of spun-yarn (k), at some distance from the man who is serving, and passes it round, as he turns the mallet, by which he is not retarded in the operation. The end is put through the three or four last turns of the service, and hauled taut.

Spike-serving is used when you have a small eye or similar piece of gear to serve. The turns are passed by hand, and each is hove taut separately by taking a marlingspike-hitch over a marling-spike, and with the point prizing it against the rope until the service is taut.

Whipping a Rope, Fig. 157, Plate 22, is done to prevent the end from fagging out. Place the end of the whipping stuff in the lay of the rope, pointing up towards the end, and pass a few turns round the rope, binding the end of the whipping; then laying the other end on the turns already passed, pointing downwards, pass the remainder on the bight, hauling through on the end part and cutting off.

A Sailmaker"s Whipping is put on with a needle and twine-a reef point has such a whipping. Pass a stitch through the point, take several turns, stick through again, and pass cross turns from one end of whipping to the other in the direction of the lay of the rope.

Crowning the end of a Rope is a rough substitute for a whipping. With the three strands form a crown, then stick the end once or twice as in splicing.

the crown with the three outside ones, taking them above, and covering the remaining three, which, with the heart strands, should be whipped, and cut off even. Lastly, worm the ends of the crowning strands back into the lay of the hawser, and clap stout smooth seizings close up to the crown, and at the extremity of the worming. Sometimes an artificial eye is formed with the inner strands.

To Point a Rope, Figs. 160 and C, Plate 22. Unlay the end of a rope as for splicing, and stop it. Take out as many yarns as are necessary, and make nettles: (this is done by taking separate parts of the yarns when split, and twisting them.) Comb the rest down with a knife, Fig. 158. Make two nettles out of every yarn which is left; lay half the nettles down upon the scraped part, and the other, back upon the rope, Fig. 159. Take a length of twine, which call the Filling, and pass three turns very taut, jamming them with a hitch at (a). Proceed, laying the nettles backwards and forwards as before, and passing the filling. The ends may be whipped and snaked with twine, or the nettles hitched over the filling, and hauled taut. The upper seizing must also be snaked, Fig. 160. The pointing, will appear like Fig. C: a small becket is often worked at the end, when the rope is large (g). If the tapered part be too weak for pointing, a piece of stick may be put in, proceeding as before.

Snaking is for the better securing of a seizing, which is passed round the single part of a rope, and therefore cannot be crossed. It is done by taken the end part under and over the lower and upper turns of the seizing, Fig. 161, Plate 22.

end, as in the cut, Fig. 164, all the nettles are taken up; if working from the centre towards the ends, the nettles on each side of the filling supply their own end. The turn of filling being passed and hitched as in pointing, commence hitching the nettles round the filling, hauling each taut separately, working to the left, keeping the filling taut, and going round and round. If what you are covering, contracts in circumference, you must leave out a nettle occasionally, and cut it off; and should it increase, lay fresh ones in. It is finished off by keeping the bights of the last round slack until you have passed a couple of turns of the filling and hitched it as in finishing off pointing, when in the same manner haul the bights close down, and cut the ends off.

Grafting, as understood now, is when a strap, ringbolt, or other article, is to be covered over entirely. It is done as in pointing, using instead of the rope-yarn nettles, log-line, or fishing-line, according to the size required.

A piece of rope of the required length is cut, and an eye spliced in each end, by means of which it is set up to small eyebolts under the gunwale; the rope is then marked where the puddings are to be worked. Worm the rope and form the puddings with any old stuff, such as old strands laid lengthwise along the rope, raising the pile in the centre and scraping off the ends to a taper. Or make a tapering pudding by winding spun-yarn around the rope. In forming the pudding, the sides intended to be next to the boat are flat, and the outer sides a half round.

Foxes for gaskets, &c., are made by taking a number of rope-yarns, from three upwards, according to the size intended, and twisting them on the knee, rubbing them well backwards and forwards with a piece of canvas. Spanish foxes are made by twisting single rope-yarns backhanded in the same manner.

over a pin, &c., and plaiting the three or four parts together for the length of the eye, Fig. 166. The plaiting is formed by bringing the outside fox on each side alternately over to the middle. The outside one is laid with the right hand, and the remainder held and steadied with the left. When this is done, take the other parts (b), (having shifted the eye part so that it lies over the bolt, Fig. 167), and work the whole together in the same manner; add another fox at (a), and work it for a convenient length, then diminish it towards the end, taking out a fox at proper intervals. When finished, one end must be laid up, the others plaited, and then the one end hauled through. This is the same work used in making ordinary sennit.

Turk"s Head. Take two round turns round the rope, Fig. 168, Plate 24, pass the upper bight down through the lower, and reeve the upper end down through it, Fig. 168 (a); then pass the bight up again and reeve the end over the lower bight, and up between it and the upper one, Fig. 168 (b); dip the upper down through the lower bight again, reeve the end down over what is now the upper bight, and between it and the lower, Fig. 168 (c); and so proceed, -working round to your right until you meet the other end, when you pass through the same bight, and follow the other end round and round until you have completed a plait of two, three, or more lays, as you wish. Fig. 168 (d), shows a Turk"s head of two lays.

Turk"s head worked into a Rope. This is done when the knot has to resist a strain, as the rung or round of a Jacob"s ladder. You middle the marline or nettle-stuff that you are working with, and splice a second piece into the centre so as to form a third leg; then pass an end through the rope, and haul it through to the junction of the third leg, which reeve through the third strand of the rope, bringing an end out between each strand, Fig. 169 (a), Plate 24. Then crown the ends round the rope, left-handed; slue round, and crown them back, right-handed, and the knot will appear as in the Fig. 169. Follow each part round with its own end, cut the ends off, and it will appear like a Turk"s head. With four-stranded rope use four ends.

Common Sennit is made with an odd number of nettles. If, however, an eye is to be formed, you commence with an even number-one being a short one; and after the eye is formed, the short end is worked in, or, if too long, left out and cut off-leaving an odd number to go on with. We will suppose that a reef-point is to be made of seven parts of spun-yarn:-Cut off four lengths (one being but little more than half the length of the others), middle them, toggle the bights through a becket triced up before you, halve the nettles, lay the right-hand nettle over the next one to it, bringing it over to the left, making three now on your left, and one on your right; Fig. 178, Plate 25, bring the outside nettle on the left over two, which will equalize them again; then the right over one, left over two, and so on alternately till you have worked length enough for the eye; next bring all eight parts together, halve them, and go on as at first-right over three, and left over four. When two or three lays are worked in this way, leave out the short end, and continue with seven parts-right over three, and left over three in succession. Finish off by forming a bight of the left-hand nettle when you bring it over, laying the end up; and as you work the remaining nettles in, point them down through this bight; and, when all are in, secure them in their places by hauling the bight taut through upon them, and cutting the ends off, Figs. 179 and 180.

French Sennit, like common Sennit, is made with an odd number of nettles. If about to make a harbor gasket for a royal yard in this manner, of nine parts of nettle-stuff, cut off five lengths (one being a short

8613371530291

8613371530291