valley breaks wire rope in stock

Example: Severe crown wire breaks on a 10-strand overhead crane wire rope. Crown breaks originate at the OUTSIDE of the rope at the contact point between rope and sheave/drum.

Remove the rope from service even if you find a SINGLE individual wire break which originates from inside of the rope. These so called VALLEY breaks have shown to be the cause for unexpected complete rope failures.

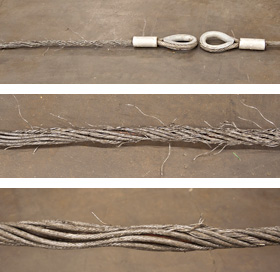

These 3 picture show what happens when you connect a left-lay rope to a right-lay rope, as done with this boom pendant extension. Both ropes are opening up to the point where the strands are nearly parallel to each other; they completely untwisted themselves and developed excessive wire breaks.

The result of such non-tensioning of the layers are looping of individual wires, completely crushed strands, total deterioration of a non-rotating rope due to gross neglect of inspection procedure.

NOTE: For a more indepth discussion on wire rope discard and inspection we suggest to attend our “Wire Rope” and “SlingMax® Rigger’s Mortis Seminar”. Call 1.800.457.9997 for details and dates.

Like all industrial equipment, aircraft cables and wire ropes wear while in service, and will require replacement. Though the cycle life of each cable varies based on construction and application, factors such as load and pulley condition can actually reduce this lifespan by triggering wire breaks. Not all wire breaks look the same, and understanding these differences can help detect issues in your system before they damage additional cables, or put human lives in danger. Here is a quick guide to help you understand where wire breaks occur (crowns vs. valleys), and three common examples of wire breaks (tension, fatigue, and abrasion).

Wire breaks typically occur in two different locations on the outside of wire rope or aircraft cable. The first location is on the crowns of the strands, which are the highest points with the most surface area exposure. The second location is the valleys, or the spaces between the strands. Though crown breaks typically result from normal wear and tear, valley breaks are more suspicious and may indicate issues with the pulley system or wire rope itself.

Wires that have been worn to a knife-edge thinness are characteristic of abrasion breaks. Abrasion can occur from a number of different sources, but sheaves are the most common. Remember to check sheaves for signs of wear, damage, or deformity and replace as necessary.

If you notice one end of a broken wire is cupped, and the other end resembles a cone, your wire rope likely experienced a tension break. Tension breaks result from excessive loading, causing the wires to stretch beyond their limits until they snap. Once one wire break appears, others will continue to occur if the cable is not addressed.

Fatigue damage is usually represented by zig-zag breaks with square ends. Like abrasion breaks, fatigue breaks can be triggered by a broad range of factors, including incorrect pulley size and excessive vibration. Check for worn pulleys and slack in the system to prevent issues from exacerbating.

Once you have replaced your damaged pulleys, or removed sharp obstructions in your system, begin your quote for brand new wire rope at https://strandcore.com/contact/. Our wire rope craftsmen can help you select the ideal wire rope for your application, and oftentimes provide a better solution for your existing setup. Browse our selection ofwire rope and aircraft cableonline, and do not hesitate to contact our sales team at sales@sanlo.com if you have any questions.

The following is a fairly comprehensive listing of critical inspection factors. It is not, however, presented as a substitute for an experienced inspector. It is rather a user’s guide to the accepted standards by which wire ropes must be judged. Use the outline to skip to specific sections:

Rope abrades when it moves through an abrasive medium or over drums and sheaves. Most standards require that rope is to be removed if the outer wire wear exceeds 1/3 of the original outer wire diameter. This is not easy to determine, and discovery relies upon the experience gained by the inspector in measuring wire diameters of discarded ropes.

All ropes will stretch when loads are initially applied. As a rope degrades from wear, fatigue, etc. (excluding accidental damage), continued application of a load of constant magnitude will produce incorrect varying amounts of rope stretch.

Initial stretch, during the early (beginning) period of rope service, caused by the rope adjustments to operating conditions (constructional stretch).

Following break-in, there is a long period—the greatest part of the rope’s service life—during which a slight increase in stretch takes place over an extended time. This results from normal wear, fatigue, etc.

Thereafter, the stretch occurs at a quicker rate. This means that the rope has reached the point of rapid degradation: a result of prolonged subjection to abrasive wear, fatigue, etc. This second upturn of the curve is a warning indicating that the rope should soon be removed.

In the past, whether or not a rope was allowed to remain in service depended to a great extent on the rope’s diameter at the time of inspection. Currently, this practice has undergone significant modification.

Previously, a decrease in the rope’s diameter was compared with published standards of minimum diameters. The amount of change in diameter is, of course, useful in assessing a rope’s condition. But, comparing this figure with a fixed set of values can be misleading.

As a matter of fact, all ropes will show a significant reduction in diameter when a load is applied. Therefore, a rope manufactured close to its nominal size may, when it is subjected to loading, be reduced to a smaller diameter than that stipulated in the minimum diameter table. Yet under these circumstances, the rope would be declared unsafe although it may, in actuality, be safe.

As an example of the possible error at the other extreme, we can take the case of a rope manufactured near the upper limits of allowable size. If the diameter has reached a reduction to nominal or slightly below that, the tables would show this rope to be safe. But it should, perhaps, be removed.

Today, evaluations of the rope diameter are first predicated on a comparison of the original diameter—when new and subjected to a known load—with the current reading under like circumstances. Periodically, throughout the life of the rope, the actual diameter should be recorded when the rope is under equivalent loading and in the same operating section. This procedure, if followed carefully, reveals a common rope characteristic: after an initial reduction, the diameter soon stabilizes. Later, there will be a continuous, albeit small, decrease in diameter throughout its life.

Deciding whether or not a rope is safe is not always a simple matter. A number of different but interrelated conditions must be evaluated. It would be dangerously unwise for an inspector to declare a rope safe for continued service simply because its diameter had not reached the minimum arbitrarily established in a table if, at the same time, other observations lead to an opposite conclusion.

Corrosion, while difficult to evaluate, is a more serious cause of degradation than abrasion. Usually, it signifies a lack of lubrication. Corrosion will often occur internally before there is any visible external evidence on the rope surface.

Pitting of wires is a cause for immediate rope removal. Not only does it attack the metal wires, but it also prevents the rope’s component parts from moving smoothly as it is flexed. Usually, a slight discoloration because of rusting merely indicates a need for lubrication.

Severe rusting, on the other hand, leads to premature fatigue failures in the wires necessitating the rope’s immediate removal from service. When a rope shows more than one wire failure adjacent to a terminal fitting, it should be removed immediately. To retard corrosive deterioration, the rope should be kept well lubricated with a clear wire rope lube that can penetrate between strands. In situations where extreme corrosive action can occur, it may be necessary to use galvanized wire rope.

Kinks are tightened loops with permanent strand distortion that result from improper handling when a rope is being installed or while in service. A kink happens when a loop is permitted to form and then is pulled down tight, causing permanent distortion of the strands. The damage is irreparable and the sling must be taken out of service.

Doglegs are permanent bends caused by improper use or handling. If the dogleg is severe, the sling must be removed from service. If the dogleg is minor, exhibiting no strand distortion and cannot be observed when the sling is under tension, the area of the minor dogleg should be marked for observation and the sling can remain in service.

Bird caging results from torsional imbalance that comes about because of mistreatment, such as sudden stops, the rope being pulled through tight sheaves, or wound on too small a drum. This is cause for rope replacement unless the affected section can be removed.

Particular attention must be paid to wear at the equalizing sheaves. During normal operations, this wear is not visible. Excessive vibration or whip can cause abrasion and/or fatigue. Drum cross-over and flange point areas must be carefully evaluated. All end fittings, including splices, should be examined for worn or broken wires, loose or damaged strands, cracked fittings, worn or distorted thimbles and tucks of strands.

After a fire or the presence of elevated temperatures, there may be metal discoloration or an apparent loss of internal lubrication. Fiber core ropes are particularly vulnerable. Under these circumstances the rope should be replaced.

Continuous pounding is one of the causes of peening. This can happen when the rope strikes against an object, such as some structural part of the machine, or it beats against a roller or it hits itself. Often, this can be avoided by placing protectors between the rope and the object it is striking.

Another common cause of peening is continuous working-under high loads—over a sheave or drum. Where peening action cannot be controlled, it is necessary to have more frequent inspections and to be ready for earlier rope replacement.

Below are plain views and cross-sections show effects of abrasion and peening on wire rope. Note that a crack has formed as a result of heavy peening.

Scrubbing refers to the displacement of wires and strands as a result of rubbing against itself or another object. This, in turn, causes wear and displacement of wires and strands along one side of the rope. Corrective measures should be taken as soon as this condition is observed.

Wires that break with square ends and show little surface wear have usually failed as a result of fatigue. Such fractures can occur on the crown of the strands or in the valleys between the strands where adjacent strand contact exists. In almost all cases, these failures are related to bending stresses or vibration.

If diameter of the sheaves, rollers or drum cannot be increased, a more flexible rope should be used. But, if the rope in use is already of maximum flexibility, the only remaining course that will help prolong its service life is to move the rope through the system by cutting off the dead end. By moving the rope through the system, the fatigued sections are moved to less fatiguing areas of the reeving.

The number of broken wires on the outside of a wire rope are an index of its general condition, and whether or not it must be considered for replacement. Frequent inspection will help determine the elapsed time between breaks. Ropes should be replaced as soon as the wire breakage reaches the numbers given in the chart below. Such action must be taken without regard to the type of fracture.

* All ropes in the above applications—one outer wire broken at the point of contact with the core that has worked its way out of the rope structure and protrudes or loops out of the rope structure. Additional inspection of this section is required.

Rope that has either been in contact with a live power line or been used as “ground” in an electric welding circuit, will have wires that are fused, discolored and/or annealed and must be removed.

On occasion, a single wire will break shortly after installation. However, if no other wires break at that time, there is no need for concern. On the other hand, should more wires break, the cause should be carefully investigated.

On any application, valley breaks—where the wire fractures between strands—should be given serious attention. When two or more such fractures are found, the rope should be replaced immediately. (Note, however, that no valley breaks are permitted in elevator ropes.)

It is good to remember that once broken wires appear—in a rope operating under normal conditions—a good many more will show up within a relatively short period. Attempting to squeeze the last measure of service from a rope beyond the allowable number of broken wires (refer to table on the next page) will create an intolerably hazardous situation.

Recommended retirement criteria for all Rotation Resistant Ropes are 2 broken wires in 6 rope diameters or 4 broken wires in 30 rope diameters (i.e. 6 rope diameters for a 1″ diameter rope = 6″).

Distortion of Rotation Resistant Ropes, as shown below, can be caused by shock load / sudden load release and/or induced torque, and is the reason for immediate removal from service.

Wire Rope is an item often found on Wire Rope Cranes. Unfortunately, though these wires are not unbreakable and can/will succumb to the pressure of constant use and may potentially snap when in use. Which is why it is important to know what to look out for in an unsafe wire rope, the Government of Canada recommends a visual inspection of the wire before each use, but full inspections should be undertaken by a trained professional periodically. This article will cover what causes wire ropes to break, what your professional inspector will do to ensure your rope is safe and what you can look out for when completing your frequent inspection to ensure the rope is safe to work with.

When you hear the term wire rope you may picture in your mind a metal and seemingly unbreakable rope, and through wire ropes, can and will stand up better than many other rope types it is unfortunately not unbreakable. Some things that can cause a wire rope to break include:

Kinks caused by improper installation of a rope, sudden release of a load or knots that were made to shorten a rope can cause the rope to become compromised

Many of these causes can be minimized by the use of proper crane design and rope maintenance procedures, most of these causes though are unavoidable and are considered to be part of a normal rope life. The two main causes that are considered unavoidable are crushing and internal and external fatigue.

Many wire ropes are subject to a lot of repetitive bending over a sheave, which causes the wire to develop cracks in its individual wires. These broken wires often develop in the sections that move over sheaves. This process will become escalated if a rope travels on and off of a grooved single layer drum, which causes this to go through a bending cycle. Tests in the past have shown that winding on a single layer drum is equal to bending over a sheave because it causes similar damage.

Fatigue breaks often develop in segments as stated before these segments are usually the part of the rope surface that comes into direct contact with a sheave or drum. Because this is caused by external elements rubbing, oftentimes these breakages are external and visible for the eye to see. Once broken wires start to appear, it creates a domino effect and quickly much more will appear. Square ends of wires are common for fatigue breaks. These breaks are considered a long-term condition and are to be considered part of the normal to the operating process.

Internal Breaks,these breaks can develop over time-based upon the loading of the hoist. Many ropes are made of a torque-balanced multi-strand design, which comprises of two or more layers of strands. A torque balance is created in multi-strand ropes, by layering the outside and inside ropes in opposite directions. Multi-strand ropes offer much more flexibility and have a more wear-resistant profile. Though the wires in these ropes touch locally and at an angle, which causes them to be subject to both the effect of radial load, relative motion between wires and bending stresses when bent on sheaves or drums.

Nicking and fatigue patterns such as the ones discussed before occur in Independent Wire Rope Cores or IWRC ropes. IWRC ropes have outer wires of the outer strands, which have a larger diameter than the outer core strands. This helps to minimize inner strand nicking between the outer strands of the IWRC. The outer strands and the IWRC strands are approximately parallel. Often their neighbouring strands support these outer strands while the outer IWRC wires are relatively unsupported.

With these geometrical features it allows for the wire to fluctuate under tensile loads, the outer IWRC wires are continuously forced into valleys in between the outer strand wires and then released. This system results in secondary bending stresses which leads to a large number of core wires with fatigue breaks. These breaks are often close together and form in groups. This eventually leads to the IWRC breaking or completely disintegrating into short pieces of wire that lay, half a length long. This condition is often called complete rope core failure.

It is as the IWRC fails, and the outer strands lose their radial support then valley breaksform. Valley breaks occur when the outer strand wires bear against each other tangentially. This results in interstrand nicking, which restricts the movement of strands within the rope; without the freedom to move, secondary fatigue breaks occur in the outer strands, which will develop a stand tangent points. These breaks occur in the valleys between the outer strands hence why they are called valley breaks.

So to go over what we just learned, internal broken wires occur often in ropes that are operated with large diameter sheaves and high factors of safety. These breakages can occur when a reeving system incorporates sheaves lined with plastic or all plastic sheaves; these sheave units offer more elastic support than their steel counterparts. Which causes the pressure between outer wires and sheave grooves to be reduced to the point where the first wire breaks will occur internally.

If a section of a rope travels on and off of a grooved multi-layer drum, then it goes through what is called a bending cycle. The bending cycle occurs by a section of rope spooling in the first layer and is bent around the smooth drum surface, but when the second layer rolls around the rope section in the first layer will be spooled over. This causes the first layer to become compressed and damaged on the upper side by the second rope layer. With continued spooling the rope layers in the second and higher layers will, in turn, be damaged on both sides during contact with their neighbouring rope layers. This damage is caused both by the compression of the rope and by the rope laying on a rough surface.

Accelerated wear occurs where the point of the rope is squeezed between the drum flange and the previous layer. Often times the slap of rope at the crossover points causes peening, martensitic embrittlement and/or wire plucking, further associated rope damage is caused when the rope crosses over from layer to layer on a drum.

Also, if the lower wire rope areas where not spooled under sufficiently high tension the lower wraps can become displaced by the additional rope sections which would allow for these new rope sections to slide down in between them, which will lead to severe rope damage.

Many regulators have decided that the Statutory Life Policy be overly wasteful and they tend to use the Retirement for Clause Policy. A wire rope deteriorates slowly over its entire service, but to be aware of the state of deterioration, a wire rope must be periodically inspected. Moderate deterioration is normally present, and low levels of deterioration do not justify retirement. Which is why you have wire rope inspections to monitor the normal process of deterioration. This ensures that the rope can be retired before it can become dangerous. Besides, these inspections can detect unexpected damage or corrosion on the wire rope which will allow you to take corrective actions to ensure the longevity of the wire rope.

This system is useful for detecting external rope deterioration. To use this approach, the inspector will lightly grab the rope with a rag. The inspector then glides the cloth over the rope. Often times external broken wires will porcupine (stick up). When the rope moves along the wire it will be snagged on the broken wire. The inspectorwill then stops dragging the cloth along the wire and visually inspects the condition of the wire.

Frequently broken wires often do no porcupine, which is why a different test procedure must be utilized. This test involves moving along the rope two or three feet at a time and visually examining the rope. This method though can become tiresome because oftentimes the rope is covered in grease and many internal and external defects will avoid detection through this method.

Another method involves measuring the wire ropes diameter. This involves comparing the diameter of the current rope to the original rope’s diameter. Changes in the diameter of the rope indicate external and/or internal rope damage. This method is not perfect because many different wire breakages damages do not change the diameter of the rope.

You can also check for several visible signs of distributed losses of the metallic cross-sectional area. This is often caused by corrosion, abrasion and wear. To internally check for damage, you can insert a marlinspike under two strands and rotate it to lift the strands and open the rope.

Visual inspections are often not well suited for the detection of internal rope damage. This means that they have limited value as the only means of wire rope inspection. Though visual inspections do not require special machines. When completed by a knowledgeable and experienced rope examiner through visual inspections can be valuable tools for evaluating rope degeneration.

Electromagnetic Inspections or EM gives a detailed insight into the exact condition of a rope. EM is a very reliable inspection method and is a universally accepted method for inspecting wire ropes for mining, ski lifts and other similar industries. There are two distinct EM inspection methods, which have been developed to classify defects called Localized-Flaw (LF Inspection) and Loss-of-Metallic-Area Inspection (LMA Inspection type)

LF Inspection is similar to the rag-and-visual method. This inspection method is suited primarily for finding localized flaws, such as broken wires. Which is why small hand-held LF instruments are called electronic rags.

Electromagnetic and visual wire rope inspection methods are like peanut butter and jelly or cookies and milk they are the perfect combination, and both are essential for safe rope operation. Which is why both methods are often used to ensure maximum safety.

A program that involves periodic inspections is extremely effective. To establish baseline data for future inspections, a wire rope inspection program should begin with an initial inspection after a break-in period. Then the inspections should follow at scheduled intervals, with documentation of the ropes deterioration over its entire service life.

For multi-strand ropes often times visual inspections are ineffective which is why statutory life policy for a ropes retirement is often adopted. This means that these ropes are often discarded long before they should be meaning millions of dollars’ worth of perfectly good wire ropes are being thrown away annually.

Some people have suggested that non-rotating ropes should not be used if cranes use a single layer winding on a drum. Following this line of thought, this would mean multi-strand ropes should be used only when winding on multi-layer drums. This would cause wires to break the surface faster than internal wire damage can occur, these non-rotating wire ropes will be replaced long before internal fatigue can set in.

When internal broken wires are the problem electromagnetic rope testing can be the solution. Though there are some factors one needs to take into account such as certain regulations require rope retirement when a certain number of broken wires per unit of rope length exceed a set limit. This discard number that is specified in retirement standards refers solely to external wire breaks. This means the condition of a wire rope with internal breaks is therefore left up to the inspector.

Though you also need to take into account detailed detection and quantitative characterization of internal broken wires in ropes with many breaks and cluster breaks could be a problem. These difficulties are caused by the fact that electromagnetic wire rope can be influenced by several parameters such as:

Clusters of broken wires can cause an additional problem because the relative position of broken wires concerning each other within the rope is not known

Broken wires with zero or tight gap widths are not detectable by electromagnetic inspection because they do not have a sufficient magnetic leakage flux.

When you consider all of this you can quickly realize that you can only estimate the number of broken wires that have formed on a wire rope. You can use the LF trace for the detection of broken wires, though unfortunately it is not quantitative so it cannot be used to estimate the number of broken wires. Though it is good to note that if any internal broken wires are present an LMA trace will show rapid relatively small variations of a cross-section.

An electromagnetic inspection will help to enhance the accuracy and reliability of the inspection, by combining visual and EM methods they will be able to detect deterioration at the earliest stages. The inspections can be then used as an effective preventive maintenance tool. For example, the inspector early on detects corrosion, and you immediately apply the corrective action of improving the lubrication of the wire rope.

Wire ropes should be inspected by a certified inspector when installing it, and periodically throughout its life cycle. A wire rope should go through a quick, but thorough inspection every day that you use it at the beginning and end of each shift and you should keep records of all inspections. Ensure that your certified wire rope inspector uses a combination of visual inspection methods and electromagnetic inspection methods because this will ensure the optimum safety and longevity of the rope. This is especially true for ropes that are more likely to develop internal broken wires, and inspections completed by a certified inspector is the best way of having a preventive maintenance program and extending the life of your wire rope.

Queensland Division of Workplace Health and Safety, “Non-rotating hoist wire ropes, multi fall configurations, Health and Safety Alert,” http://www.whs.qld.gov.au/alerts/97-i-5.pdf

Verreet, R. “Wire rope damage due to bending fatigue and drum crushing,” O.I.P.E.E.C.(International Organization for the Study of the Endurance of Wire Rope) Bulletin 85, June 2003, Reading (UK), ODN 0738, pp. 27-46.

Any wire rope in use should be inspected on a regular basis. You have too much at stake in lives and equipment to ignore thorough examination of the rope at prescribed intervals.

The purpose of inspection is to accurately estimate the service life and strength remaining in a rope so that maximum service can be had within the limits of safety. Results of the inspection should be recorded to provide a history of rope performance on a particular job.

On most jobs wire rope must be replaced before there is any risk of failure. A rope broken in service can destroy machinery and curtail production. It can also kill.

Because of the great responsibility involved in ensuring safe rigging on equipment, the person assigned to inspect should know wire rope and its operation thoroughly. Inspections should be made periodically and before each use, and the results recorded.

When inspecting the rope, the condition of the drum, sheaves, guards, cable clamps and other end fittings should be noted. The condition of these parts affects rope wear: any defects detected should be repaired.

To ensure rope soundness between inspections, all workers should participate. The operator can be most helpful by watching the ropes under his control. If any accident involving the ropes occurs, the operator should immediately shut down his equipment and report the accident to his supervisor. The equipment should be inspected before resuming operation.

The Occupational Safety and Health Act has made periodic inspection mandatory for most wire rope applications. If you need help locating the regulations that apply to your application, please give our rigging experts a call.

Information about wire rope unloading, storage, handling, installation, operation, lubrication, inspection, maintenance and possible causes for rope faults is given in this article to get best service from it.

Whenever handling wire rope, take care not to drop reels or coils. This can damage wire rope and collapse the reel, making removal of the wire rope extremely difficult. Rope in a coil is unprotected and may be seriously damaged by dropping.

Wire ropes should be stored in a well ventilated, dry building or shed and shall not be in contact with the floor. If it is necessary to store them outside, cover them so that moisture cannot induce corrosion. The place should be free from dust, moisture and chemical fumes. To protect the wooden reels from the attack of termites, the floor should be cemented. Turning the reel occasionally, about half a turn, helps prevent migration of the rope lubricant. If ropes are to be stored for long time, it is advisable to examine them periodically and to apply dressing of lubricant to the top layer of rope on the drum.

Care must be taken when removing wire rope from reels or coils. When removing the rope from the reel or coil, the reel or coil MUST rotate as the rope unwinds. The Following illustrations demonstrate the right and wrong way of unreeling a rope.

For unreeling a reel, a spindle should be put through the reel and its ends jacked up to allow free rotation of the reel when the rope end is pulled. Rope in coil should be paid out from a turntable. Alternatively, where a coil is of short length, the outer end of the coil may be made free and the remainder rolled along the ground. Any attempt to unwind a rope from stationary reel or coil WILL result in a kinked rope. Looping the rope over the flange of the reel or pulling the rope off a coil while it is lying on the ground will create loops in the rope. If these loops are pulled tight, kinks will result.

A kink is a permanent deformation or reshaping of rope. Kink leads to imbalance of lay length which will cause excessive wear. In severe cases, the rope will be so distorted that it will have only a small proportion of its strength. Thus a kink in wire rope results into premature wire rope failure. One of the most common causes for its formation is improper uncoiling and unrelling. If for any reason, a loop does form, ensure that it does not tighten to cause a kink which may lead to distortion of the rope.

When reeling wire rope from one reel to another or during installation on a drum it shall always bend in the same direction: i.e. pay out from the top of the reel to the top of the other reel, or from the bottom of the reel to the bottom of the other reel as illustrated below.

If wire rope is required to be cut, it shall be seized before cutting. Seizing is warping of soft iron wire around a wire rope to prevent its wires from “flying apart” when the wire rope is cut between two adjacent seizing. Proper seizings must be applied on both sides of the place where the cut is to be made. Two or more seizing are required on each side. Either of the following seizing methods is acceptable. Method No. 1 is usually used on wire ropes over one inch in diameter. Method No. 2 is applied to ropes one inch and under.

For Method No. 1, place one end of the seizing wire in the valley between two strands. Then turn its long end at right angles to the rope and closely and tightly wind the wire back over itself and the rope until the proper length of seizing has been applied. Twist the two ends of the wire together to complete seizing. For Method No. 2, wind the wire on the rope until the proper length of seizing has been applied. Twist the two ends of the seizing wire together to complete seizing.

The length of seizing and the diameters of the wires used for seizing depend on the wire rope diameter. Length of seizing shall be greater than two times the rope diameter. Suggested seizing wire diameters are as under.

After cutting the rope it is a good practice to braze rope ends to ensure that they don"t unravel. Leave the seizings on the rope for added holding strength. As cutting a rope with a torch may result in uneven ends, it may be cut by wire rope cutter (in case of small size ropes) or by grinding. Sometime rope ends are seized with hose clamps.

It is important to maintain the manufactured condition of the rope. Take care to prevent turn being put in or taken out of the rope. If turn is put in, core protusion is likely whereas if turns are taken out, bird caging of outer wires may occur.

Installation of wire rope on a plain or grooved drum requires a great deal of care. Whenever practicable, not more than one layer of rope should be wound on a drum. Be sure to use the correct rope lay direction for the drum. This applies to smooth, as well as grooved drums. The easiest way to identify correct match between rope and drum is to look alongside the drum axis and the rope axis. The direction of rope lay and drum groove must be opposite to each other.

Make certain that wire rope is properly attached to the drum. The lay of the rope shall not be disturbed during installation, i.e. turn should not be put in nor taken out of the rope. Start winding the rope in a straight helix angle. To assist with this, some drums have a tapered steel part attached to one flange which "fills" the gap between the first turn and the flange as shown below.

The first layer must be wound tight and under tension. Take a mallet or a piece of wood and tap the wraps tightly against each other such that the rope can"t be shifted on the drum. They should not be so tight that the rope strands interlock. A too tightly wrapped first layer will not allow the next layers to have enough space between wraps. In such cases rope strands in second layer will also get interlocked as shown below.

In any case, the first layer, as well as all of the layers, must be wound on to the drum with sufficient pre-tension (about 5-10% of the rope"s WLL). If wound with no tension at all, the rope is subjected to premature crushing and flattening caused by the "under load" top layers as shown below.

After installing a new rope, it is necessary to run it through its operating cycle several times (known as break in period) under light load (approximately 10 % of the Working Load Limit) and at reduced speed. Start with light loads and increase it gradually to full capacity. This allows the rope to adjust itself to the working conditions and enable all strands and wires to become seated. Depending on rope type and construction some rope stretch and a slight reduction in rope diameter will occur as the strands and core are compacted. The initial stretch (constructional stretch) is a permanent elongation that takes place due to slight lengthening of the rope lay and associated slight decrease in rope diameter. Constructional stretch generally takes place during the first 10-20 lifts, and increases the rope length by approximately ½ % for fiber core rope, ¼ % for 6-strand steel core rope, and approaches zero % for compacted ropes.

Wire Ropes are usually made slightly larger than nominal diameter to allow for reduction in size which takes place due to the compacting of the structure under load (break in period). Keep a record of the new rope diameter after break in period for future reference.

In many cases the equipment has to be tested prior to use. Proof testing requires to purposely overloading the equipment to varying degrees. The magnitude of overloading depends on specification and which governing authority certifies the equipment. The test may impose an overload of between 10% and 100% of the equipment"s rated capacity. Under NO circumstances must the equipment be tested prior to the break in procedure of the wire rope. If you overload a rope which has not yet been broken in, you may inflict permanent damage to the rope.

Equipment consisting of wire ropes shall be operated a by well-trained operator only. A well-trained operator can prolong the service life of equipment and reduce costs by avoiding the potentially hazardous effects of overloading equipment, operating it at excessive speeds, taking up slack with a sudden jerk, and suddenly accelerating or decelerating equipment. The operator can look for causes and seek corrections whenever a danger exists. He or she can become a leader in carrying out safety measures – not merely for the good of the equipment and the production schedule, but, more importantly, for the safety of everyone concerned.

It is a common practice to leave a crane idle from one day to another or over a week end, with the rope at one position. This practice should be varied; otherwise the same part of the rope is constantly left on a bend leading to faster deterioration of that part of the rope.

Although every rope is lubricated during manufacture, to lengthen its useful service life it must also be lubricated "in the field." A rope dressing of grease or oil shall be applied during installation. Subsequently the wire rope shall be cleaned and relubricated at regular intervals before the rope shows signs of dryness or corrosion. Wire rope may be cleaned by a wire brush, waste or by compressed air to remove all the foreign material and the old lubricant from the valleys between strands and wires. After cleaning the rope, it should never be cleaned using thin oils like kerosene or gasoline as it may penetrate into the core and do away with the internal lubrication. The use of relatively fluid dressings is sometimes preferred, which can easily penetrate between the outer wires of the rope, and displace any water, which may have entered. New lubricant may be applied by a brush or may be dripped on to the rope preferably at a point where the rope opens because of bending as shown below.

When ropes are to be stored for prolonged periods or used for special operating conditions, the heavier bituminastic type of dressing is preferable to low viscosity dressings, which tend to drain off the rope, thus exposing it to corrosion.

The lubricant used must be free from acids and alkalies and should have good adhesive strength (should be such that it cannot be easily wiped off or flung off by centrifugal force). It should be able to penetrate between the wires and strands. It should not decompose, have high film strength and resist oxidation.

Frequency of lubrication depends on operating conditions. The heavier the loads, the greater the number of bends, or the more adverse the conditions under which the rope operates, the more frequently lubrication will be required.

It is essential to inspect all running ropes at regular intervals so that the rope is discarded before deterioration becomes dangerous. In most cases there are statutory and/or regulatory agencies whose requirements must be adhered to. As life of wire rope is affected by condition of drum and sheaves, their inspection and maintenance also shall be carried out.

Regular external and internal inspection of a rope shall be carried out to check for its deterioration due to fatigue, wear and corrosion. It should be checked for the following criteria. The individual degrees of deterioration should be assessed, and expressed as a percentage of the particular discard criteria. The cumulative degree of deterioration at any given position is determined by adding together the individual values that are recorded at that position in the rope. When the cumulative value at any position reaches 100 %, the rope should be discarded.

The occasional premature failure of a single wire shortly after installation may be found in the rope life and in most cases it should not constitute a basis for rope removal. Note the area and watch carefully for any further wire breaks. Remove the broken ends by bending the wire backwards and forwards. In this way the wire is more likely to break inside the rope where the ends are left tucked away between the strands. These infrequent premature wire breaks are not caused by fatigue of the wire material

The rope must be replaced if a certain number of broken wires are found which indicate that the rope has reached its finite fatigue life span. Wire rope removal/retirement criteria based on number of broken wires are given in ASME B30 and ISO 4309 specifications.

Tensile wire breaks are characterized by their typical "cup and cone" appearance as shown below. The necking down of the wire at the point of failure to form the cup and cone indicates that the failure has occurred while the wire retained its ductility.

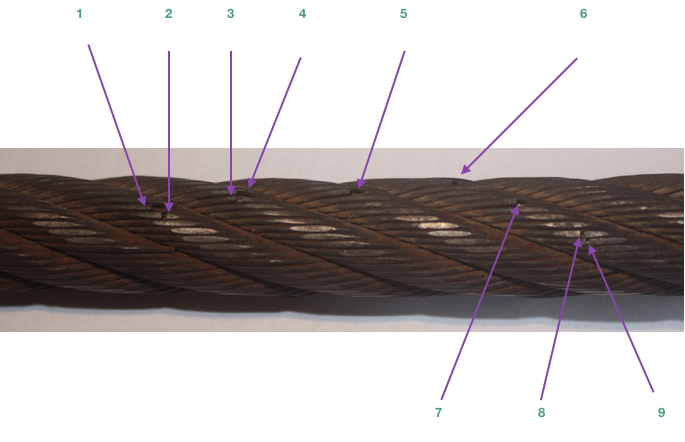

Under normal operating conditions single wires will break due to material fatigue on the crown of a strand. Crown breaks originate at the outside of the rope at the contact point between rope and sheave/drum as shown below.

Valley breaks originate inside the rope and are seen in the valley between two strands. Valley breaks hide internal wire failures at the core or at the contact between strand and core. Valley break may indicate internal rope deterioration, requiring closer inspection of this section of rope. Picture of a rope with valley brake wires is given below.

Crown breaks are signs of normal deterioration, but valley breaks indicate an abnormal condition. Generally extreme notching and countless wire breaks is found in core (complete core failure) when valley breaks are noticed. Such condition will result in catastrophic rope failure and hence it is recommended to remove wire rope from service even if a single valley wire break is detected.

All wire rope removal/retirement criteria are based on fatigue wire breaks located at the crown of a strand. Table as per ASME specification showing maximum number of broken crown wires is as under. The removal criteria are based on the use of steel sheaves.

Broken wires at or near the termination indicates high stresses at that position. It can be due to incorrect fitting of the termination. The cause of this deterioration shall be investigated and the termination remade by shortening the rope if sufficient length remains for further use. If this is not possible, the rope shall be discarded.

In applications where major cause of rope deterioration is fatigue, broken wires will appear after a certain period of use and the number of breaks will progressively increase with usage time. In such cases it is recommended that careful periodic examination and recording of the number of broken wires is carried out with a view to establish the rate of increase in the number of broken wires. The trend can be used to plan wire rope replacement.

The round outer wires of standard wire rope will become flat on the outside due to friction when they come in contact with drums, sheaves, or other abrasive matter like sand or gravel. This is part of normal service deterioration. As shown below, when the surface wires are worn by 1/3 or more of their diameter, the rope must be replaced.

There will be always a normal continuous small decrease in diameter throughout the rope"s service life. Diameter reduction after the break in period is often due to excessive abrasion of the outside wires, internal or external corrosion, inner wire failures and/or inner wire abrasion and deterioration of a fibre core / fracture of a steel core. When core deterioration occurs, it is revealed by a more rapid reduction in diameter. Rope shall be replaced when core deterioration is observed.

Corrosion, while difficult to evaluate, is a more serious cause of degradation than abrasion. It reduces the breaking strength of the rope by reducing the metallic cross-sectional area, and also accelerates fatigue by causing surface irregularities which lead to stress cracking. Usually, it signifies a lack of lubrication. Corrosion often occurs internally before there is any visible external evidence on the rope surface. Corrosion also prevents the rope"s component parts from moving smoothly.

Visible distortion of the rope from its normal shape is termed “deformation” or damage. It is not repairable. It leads to uneven stress distribution in the rope. The magnitude of the deformation may vary from a slight cosmetic damage to total destruction of the wire rope. Kink, crushing, birdcage (also know as basket or lantern formation), core or strand protrusion and wire protrusion are various types of deformations.

Crushing or flattening of the strands can be caused by a number of different factors. These problems usually occur on multilayer spooling applications. Generally crushing conditions occur because of improper installation of the wire rope.

Birdcage is a result of a difference in length between the rope core and the outer layer of strands. Different mechanisms can produce this deformation. For example, when a rope is running over a sheave or onto the drum under a large fleet angle, it will touch the flange of the sheave or the drum groove first and then roll down into the bottom of the groove. This characteristic will unlay the outer layer of strands to a greater extent than the rope core, producing a difference in length between these rope elements. Shock loading also leads to birdcage formation. A birdcage looks as shown below.

Core or strand protrusion is a special type of birdcage in which the rope imbalance is indicated by protrusion of the core between the outer strands, or protrusion of an outer strand of the rope or strand from the core. A photograph of core protrusion is shown below.

As wire rope performance depends upon the condition of the equipment on which it operates, to increase life of a wire rope, corrective actions shall be taken after checking of wire rope at cross points, wedge sockets and other components of a machine like sheave and drums as under.

On multiple layer drums, wire rope will wear out at the crossover points from one wrap to the next. At these crossover points, the rope is subjected to severe abrasion and crushing as it is pushed over the rope "grooves" and rides across the crown of the layer beneath as shown below.

In order to extend the rope"s working life, shortening of the rope at the drum anchoring point of approx. 1/3 of the drum circumference, moves the crossover point to a different section of the rope. Now, a rope section previously not subjected to scrubbing and crushing will take the workload

Replace the sheaves with broken flanges as it enables wire rope to jump the sheave and become badly cut or sheared. If sheaves are wearing on one side, correct the alignment.

Check the sheave / bearings for ease of rotation and wear. Worn bearings cause vibration in the rope, increasing wire fatigue. Repair the bearings or replace the sheave.

Last article, we talked about what to look for during a wire rope inspection. This month, we will talk about where and how to look for damage on a wire rope.

Much of a wire rope can be in good working order, while some sections may still be at the point of replacement or failure. This premature wear occurs at points where the rope bends over a sheave or, during drill operations, winds onto a drum during initial loading. On a drill rig, most of the time we apply a load to a winch, we either pick up a rod or piece of casing at the table, or at a rod box or rack. This means the same length of rope moves over the sheaves and enters the drum each time the operator applies a load. Wire rope wears much more quickly if subjected to bending because the outer wires and inner wires travel at differing speeds when going around a bend. Loading a rope while it bends increases these stresses.

The first method involves a rag or glove. With a rag or glove fully covering your hand, lightly grasp the rope as it moves at slow speed. External broken wires often stick up and, as the rope moves, snag the rag. The rope is then stopped, and the inspector assesses the condition by a visual examination. If he finds a problem, he marks the rope at the location of the broken wire. The inspector then checks the rope for broken-wire removal criteria and, if none are found, continues the inspection.

As a safety professional and a driller who has had steel splinters from a wire rope, I do not like this method. Inspections done this way run a high risk of hand injury for the inspector. Worst of all he may not even find all the deficiencies, because not all broken wires stick up and catch the rag.

Instead, I recommend a thorough, visual-only inspection. The method I prefer is to move the rope 2 or 3 feet at a time, and stop and visually inspect the rope looking at all sides. In cases where grease or grime cover the rope, clean with a wire brush or many defects may elude detection.

While inspecting, bend the rope to look for “valley breaks.” These breaks happen down where the strands contact each other and can be difficult to see unless the rope is bent. Valley breaks occur in wire rope applications involving small-diameter sheaves, sheave grooves that are too small and heavy loads. During inspection, pay close attention to areas of the rope that come in contact with sheaves and drums when picking up loads.

Make a habit of lubricating wire rope as part of any regular inspection. Wire rope is lubricated during manufacturing, but initial lubrication is not enough to last the life of the rope.

Lubrication of wire rope is as important as lubricating any other component or piece of machinery. Clean and dry wire rope before applying lubricant. Remember, actual lubrication occurs only when lubricant can encounter bare wires. For wire ropes used under working conditions, choose a lubricant that specifically says cable oil. Do not use WD-40, PB blaster or crankcase oil to lubricate wire rope.

The next thing we must look for during inspection is a reduction in diameter. This is the only approved way to determine the stability of the core of the rope. For this type of inspection, we need two numbers that we should have gotten upon installation of the wire rope: the diameter and the overall length.

Place a caliper on the widest point of the rope to get the correct diameter reading. Generally, ropes are manufactured larger than nominal diameter. When placed in service for the first time, diameter can reduce slightly. Therefore, make the initial measurement of a rope diameter after the rope’s initial loading or break-in period. Record this measurement as initial diameter on the inspection log. Remove a rope from service when its actual diameter falls to 95 percent of its nominal diameter.

The overall length of the rope to the inch acts as a good tool in determining core health. When a core fails, the length of a rope increases. Any increase in rope length is grounds for replacement.

Reeving failures have been a leading cause of accidents in our trade. They were thirty years ago when Wilbert A Lucht wrote his article, “Sheave Design vs Wire Rope Life” (reprinted in the June issue ofWire Rope News, page 26), and are still today.

A Crane is a combination of two simple machines. One is a lever, and the other is a block and tackle. Both increase the machinal advantage of a crane’s lifting capability. However, the block and tackle (sheaves and wire rope, referred to as reeving) are “used-up” as the crane works.

The sheave differs from a “pulley” or roller importantly. Both change the direction of the rope and increase the mechanical advantage — pulling power. However, the sophisticated sheave does the same but also maintains the cross-section shape of the rope, critical to reducing wear, and the rope strength — if properly sized.

A Sheave gauge is being used to check the groove size by a crane inspector in Fig. 1. These gauges have the maximum size of the groove recommended for the rope that is installed on the crane.

An oversize or worn-out sheave acts just like a pulley, not preserving the rope’s shape, Fig. 2. Instead of the load being supported by at least three strands at the bottom of the groove, all the load is concentrated on one. With less support, increased pressure equals more significant sheave wear. There is another terrible consequence of improper groove support — premature wire breaks and internal wire wear. When the unsupported rope is bent over a sheave and loaded, the strands must adjust by sliding along each other. Sliding causes strand to strand nicking and “valley” wire breaks, a severe reduction in the rope’s life, Fig. 3.

The consequence of sheaves not correctly sized to the wire rope installed on them is accelerated wear and broken wires. How important is this to the crane owner depends on how many hours of operation per inspection interval. Some cranes aren’t used much, and owners aren’t too concerned with groove size, just so the grooves are “kind of” smooth — wrong. Current standards allow only one valley break, as shown in Fig.3.

The point is, to achieve a predictable rope life — the sheave must support about 150 degrees of the rope at the bottom of the groove, or the rope will flatten when loaded and be weaken — got that!

Fiber rope and wire rope are widely used across the groundwater industry. Fiber rope is more commonly used in manual hoisting, such as raising up or lowering down tools. Wire rope is commonly used for mechanical hoisting operations.

The improper use of fiber rope or wire rope can result in serious incidents involving property damage, injuries, and death. Using the ropes as intended within their safe working load and maintaining them in good condition are critical in preventing rope failures.

Both types of rope include a combination of characteristics that give them certain performance traits depending on design, materials, and composition.

Wire rope is made of steel wires laid together to form a strand. These strands are laid together to form a rope, usually around a central core of either fiber or wire.

The number of strands, number of wires per strand, type of material, and nature of the core depend on the intended purpose of the wire rope. Wire rope that has many smaller wires and strands is more flexible than rope with larger-diameter wires and fewer strands. Wire rope used with sheaves and drums should have many strands to be flexible enough to bend around the sheaves and drums.

Wire ropes are classified by grouping the strands according to the number of wires per strand. The number of wires and the pattern defines the rope’s characteristics.

For example, a 6 × 7 rope indicates the rope is comprised of six strands and each individual strand is comprised of seven wires. This particular rope has large wires and is not very flexible but has good abrasion-resistant qualities. Whereas, a 6 × 19 rope has 19 wires per strand and thus is more flexible.

The more wires in a strand, the more flexible the wire rope. Likewise, the more strands in the rope, the more flexible the rope. However, the more strands in a rope and more wires in a strand, the less abrasion resistant.

Other important requirements to consider when selecting a wire rope are the breaking strength and “safe working load.” These values can be found with the use of a chart.

Most hoisting jobs use a safe working load based on a 5:1 safety factor of the wire rope’s breaking strength. However, this safety factor should be even higher if there is a possibility of injury or death from the rope breaking. For example, elevators are based on a 20:1 safety factor. Critical lifts with a danger to personnel should be calculated on a 10:1 safety factor.

Wire rope inspections are important checks on any type of rigging equipment. Wear, metal fatigue, abrasion, corrosion, kinks, and improper reeving are more important in dictating the life of a wire rope—more so than its breaking strength when new. Therefore, wire rope should be regularly inspected in accordance with OSHA and industry standards.

The frequency of inspections depends on the service conditions. Slings should be inspected each day before being used. Wire rope in continuous service or severe conditions should be inspected at least weekly and also observed during normal operation. For most other applications, wire rope should be inspected at least monthly.

Broken wires: Removing a wire rope from service due to broken wires depends on how the particular rope is being used. Finding one broken wire (or several widely spread) is usually not a problem. Regular breaks are a cause for concern and require a closer inspection. General guidelines for rope replacement due to broken wires are as follows:

Running wire ropes: Six randomly distributed broken wires in one rope lay or three broken wires in one strand in one rope lay, where a rope lay is the length along the rope in which one strand makes a complete revolution around the rope.

Pendants or standing wire ropes: More than two broken wires in one rope lay located in the rope beyond end connections or more than one broken wire in a rope lay located at an end connection. Slings: Ten randomly distributed broken wires in one rope lay or five broken wires in one strand in one rope lay.

Rotation-resistant ropes: Two randomly distributed broken wires in six rope diameters or four randomly distributed broken wires in 30 rope diameters. Valley breaks:Wire ropes with any wire breaks in between two adjoining strands should be removed from service.

Abrasion:Wire rope winding over drums or through sheaves will wear. The rope should be replaced if the outer wire exceeds one-third of the original diameter.

Crushed strands: This condition is a result of too many layers of rope wrapped around a drum. There should be no more than two layers of wire rope on the drum, especially if the rope is a type with many small wires (such as 6 × 37). Crushing also occurs by cross winding, which is a result of poor winding procedures when the rope is wound in a pile in the middle of a drum.

Corrosion: This problem is difficult to evaluate and is also much more serious than normal wear. Corrosion will often start inside the rope before it shows on the outside. A lack of lubrication is usually the cause. Wire pitting or severe rusting should be cause for immediate replacement.

Kinks: Kinks are permanent distortions. After a wire rope is kinked, it is impossible to straighten the rope enough to return it to its original strength. If a rope cannot be unkinked by hand, it should be removed from service.

Electric arc:Wire rope that has been inadvertently (or purposely) used as a ground in welding or has been in contact with a live power line will have fused or annealed wires, and must be removed from service.

Metal fatigue: This is usually caused by bending stress from repeated passes over sheaves, or from vibration such as crane pendants. Fatigue fractures can be external or internal. A larger sheave or drum size, or using a more flexible rope, may increase the rope life.

Diameter reduction: Any noticeable reduction in diameter is a serious deterioration problem. A wire rope is measured across its diameter at its widest point. Diameter reduction could be caused by one fault or a combination of faults. Wire ropes should be replaced when the reduction in diameter is more than 5% from the nominal diameter.

Wire rope stretch: Any new wire rope will stretch when the initial load is applied. After the initial stretch and a slight stretching over time during normal wear, the rope will begin to stretch at a quicker rate, which means it is approaching time for replacement.

Bird caging: This is a torsional imbalance, which is a result of mistreatment such as pulling rope through tight sheaves, being wound on too small a drum, or sudden stops.

A wire rope is lubricated during the manufacturing process. This provides the rope with protection for a reasonable time if stored under proper conditions. When the wire rope is in service, the initial lubrication will not be enough to last the lifetime of the rope. Therefore, it is usually necessary to apply a lubricant to a wire rope under working conditions. A light mineral oil can be used for lubrication. Never use old crankcase oil.

Fiber ropes are preferred for some rigging applications because they are more pliant. However, they should be used only on light loads and must not be used on objects that have sharp edges capable of cutting the rope. Fiber ropes should also not be used where they will be exposed to high temperatures, severe abrasion, or acids.

The choice of rope depends on its application. Manila is a natural fiber and has relatively high elasticity, strength, and resistance to wear and deterioration. Manila rope is generally the most common natural fiber rope used because of its quality and relative strength.

The principal synthetic fiber used for rope is nylon, which has a tensile strength nearly three times that of manila. The advantages of nylon rope are it is waterproof and has the ability to stretch, absorb shocks, and resume its normal length. Nylon also has better resistance against abrasion, rot, decay, and fungus growth as compared to natural fibers.

Avoid dragging rope through sand or dirt or pulling over sharp edges. Sand or grit between the fibers of the rope cuts the fibers and reduces its strength.

The outside appearance of fiber rope is not a good indication of its internal condition. The rope softens with use. Dampness, heavy strain, fraying and breaking of strands, and chafing on rough edges all weaken the rope considerably.

Overloading a rope may cause it to break. For this reason, fi

8613371530291

8613371530291