tripping pipe on a workover rig price

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

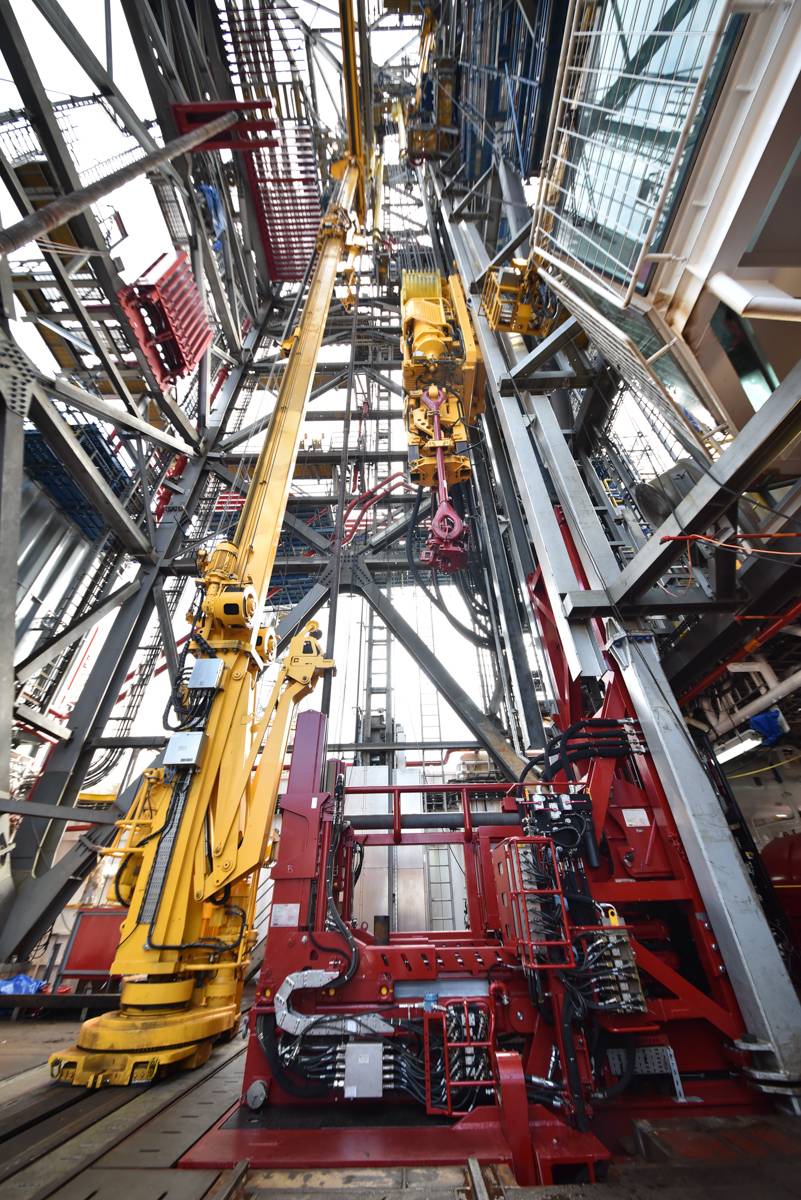

Offshore drilling services provider Ensco has rolled out a new proprietary solution engineered to provide greater pipe tripping safety and efficiency.

When used in concert with other key equipment, sensors and process controls, Ensco’s patented Continuous Tripping Technology (CTT) can fully automate the movement of the drill string into or out of the well at a constant controlled speed.

Ensco president and CEO, Carl Trowell calls the new technology “a step-change efficiency improvement that uses automation and innovative technology to address a repetitive, time-consuming process that is ubiquitous in offshore projects today.”

According to Trowell, “Tripping pipe is on the critical path for all drilling and workover activities and, as a result, meaningful time is spent performing this process over the life cycle of every offshore well.

“Continuous Tripping Technology significantly reduces the amount of time spent tripping pipe, and the faster tripping time that this technology offers is expected to lead to cost savings for customers regardless of water depth or well type,” he said.

Ensco claims CTT enables pipe-accelerated tripping speeds of up to 9,000 feet per hour when deployed during offshore activities. The constant tripping speed minimizes surge and swab pressure on the wellbore by eliminating intermittent stopping and starting as well as excessive peak speeds.

The system, which can be retrofitted to both floaters and jackups, and is particularly well-suited for ultra-deepwater drillships and larger modern jackups, uses automation to eliminate human error and personnel exposure associated with the conventional stand-by-stand method, according to its developer.

“Continuous Tripping Technology is another example of our ongoing investments in innovation that are focused on developing systems, processes and technologies to make the drilling process more efficient and lower offshore project costs for customers,” Trowell said.

“We continue to see better utilization for rigs that deliver the greatest efficiencies for customers’ offshore well programs and, given the proprietary nature of Continuous Tripping Technology, we expect that it will help to further differentiate Ensco’s assets from the competition and position us well for future contracting opportunities.”

Ensco said the CTT system was recently installed and is being commissioned on the 2016-built jack-up ENSCO 123. The rig is expected for delivery in March 2019 following system commissioning and rig acceptance trials.

Tripping pipe (or "Making a round trip" or simply "Making a trip") is the physical act of pulling the drill string out of the wellbore and then running it back in. This is done by physically breaking out or disconnecting (when pulling out of the hole) every other 2 or 3 joints of drill pipe at a time (called a stand) and racking them vertically in the derrick. When feasible the driller will start each successive trip on a different "break" so that after several trips fresh pipe dope will have been applied (when running back in the hole) to every segment of the drill string.

The most typical reason for tripping pipe is to replace a worn-out drill bit. Though there are many problems that occur to warrant the tripping of pipe. Downhole tools such as MWD (measurement while drilling), LWD (logging while drilling) or mud motors break down quite often. Another common reason for tripping is to replace damaged drill pipe. It is important to get the pipe out of the wellbore quickly and safely before it can snap.

Drill bits wear and tear like most any other piece of equipment. Once a bit becomes too worn to drill at an adequate rate or make a full-gauge hole, or if the bearings are thought to be near failure, a trip is undertaken to replace the bit. A trip is not considered a bit trip when the purpose of replacing the bit is to change sizes. This is only done when the crew "sets surface, intermediate or longstring" as appropriate.

A fishing trip is when a crew is forced to trip pipe to retrieve loose items in the wellbore. This can result from something being dropped in the hole, i.e. a tool, that would cause damage to the bit if the crew attempted to drill with it on bottom.

Another major cause is known as a "twist off". Twisting off is when the drill string parts by failing catastrophically under the torsional stress. This may happen if the drill string below is pinched in the wellbore, or as the result of a structural weakening of the pipe caused by a washout or a crack in a threaded connection member.

When pipe snaps or a part of the bit breaks off, the crew has to recover all of the separated items from the wellbore. Recovering snapped pipe usually involves placing a specialized tool (an "overshot") with grips set inside of it over the broken pipe in an attempt to capture it. The grip works in a manner similar to Chinese fingercuffs. Sometimes the jagged top of the fish must be milled back to a round outside shape before the overshot can slip over it. The overshot contains a packoff device to make a pressure seal so circulation can be reestablished through the bit to facilitate recovery of the fish. For a broken bit, a magnet is commonly used to remove all of the broken parts.

A cracked pipe can lead to a broken string. Extra care is taken when tripping for one so that too much pull does not cause the cracked pipe to snap. Cracked pipes (i.e., washouts) are usually noticed by a sudden drop in pressure. The crew will usually pump "fastline" (small lengths of manila rope taken from unraveled catline) down the drill string to make a temporary plug and time the pressure to see when it rises back to normal. This enables the crew to know how far down to expect the cracked pipe to be within a few stands; also strands of these rope segments may be seen at the point of washout. Most trips for a cracked pipe are not complete trips like a fishing trip or a bit trip. These can be as simple as only going a few stands down, to pulling the drill collars.

Logging of the open hole may take place at various depths while drilling, and almost always at the end of the drilling operation. The drill string will be removed from the wellbore to allow a logging crew to conduct a survey of the well. After the logging is completed at total depth, the crew will run the drill string back into the well and then proceed to lay it down when coming out of the hole prior to installing the final set of casing (the "production casing").

These trips are routinely expected by the crew. Setting surface occurs after the wellbore is drilled to the predetermined surface depth (e.g., after drilling below fresh water strata). The crew will remove the entire drill string to allow surface casing to be emplaced. The procedure is similar for setting intermediate, only that it typically involves a much longer drill string to be removed. Setting longstring is usually a one time operation combining both surface and intermediate casing. This saves the time of only having to undertake one pipe trip as opposed to two pipe trips.

Jereh truck/trailer mounted workover rig is mechanically and hydraulically driven. The power system, drawworks, mast, travelling system and transmission mechanism of the workover rig are mounted on the self-propelled chassis, which improves the moving efficiency greatly. Now, Jereh truck mounted workover rig series cover the workover depth from 2500m to 7000m and drawworks power from 250HP to 1000HP, featuring high operation load, reliable performance, excellent off-road performance, convenient movement and low operation/moving cost. Besides, workover rigs for arctic, desert and highland applications are available.

In oil and gas recovery operations, tubular members are usually run or pulled using a workover rig or a snubbing unit. Workover rigs are basically small drilling rigs having a derrick and drawworks, and although they are less expensive to employ than full-sized rigs, their use can still be quite costly.

Snubbing units are smaller, easier to transport and less expensive to operate than workover rigs and are often employed when working a pressurized well that requires tubular members to be forced into the wellbore.

A viable alternative that improves safety and efficiency during snubbing operations consists of a power tong set, with lead and back-up tongs that are mounted on the slip bowl of the traveling jack head of a snubbing unit and rotates with the slip bowl. Service lines for the tong set are not connected during string rotation.

In another version of this type of device, a fluid feed-through swivel is mounted on the tong set, secured to the necessary tong operating and control service fluid lines, such that the tong set can rotate with tong service lines between the tong set and the snubbing unit attached during rotation.

In an alternate form, the tong set is mounted on the jack head, independent of the rotary table, and the tong set does not rotate when the rotary table rotates.

Snubbing is an old technique dating back to the late 1920s in the United States that was primarily used in emergency situations, such as blowouts or uncontrolled wells.

Like coiled tubing techniques, snubbing allows a tubular to be run with a check valve on the end into a live well by means of specialized handling and sealing systems. However, instead of pipe coiled up on a reel, it uses tubing-type pipe lengths run in hole and made up to each other by conventional threaded connections. This means that larger-diameter pipe can be used than in the coiled tubing method.

The snubbing unit therefore offers better flow capacity, breaking load and rotation capacity and is able to put weight on the downhole tool. In contrast, tripping takes longer because the lengths of pipe have to be screwed together and the procedure for running the connections through the safety stack on the wellhead may be slow and represents a high risk for personnel if not done properly.

A snubbing unit consists basically of a pipe-handling system, a wellhead safety system, a hydraulic power unit and the downhole accessories incorporated into the snubbing string.

The pipe-handling system must be able to push the pipe into the well during the snubbing phase (also called light pipe phase), which occurs every time the pipe weight is lower than the wellbore pressure force against it.

The mobile system usually consists of only one set of single acting slips while the stationary system consists of two sets of opposing slips that keep the pipe in place, whatever the phase of the operation, and it is located below the low position of the traveling slips.

With the traveling slips closed and the stationary ones open, the pipe can be tripped over a length corresponding to the stroke of the jacks. Then, all that is required to bring the jack back to its original position is to close the stationary slips and open the traveling slips. After the traveling slips have been closed again and the stationary slips have been opened, the operation can continue.

The pipe is brought up from the pipe rack by a set of elevators, sheaves and a handling cable attached to the gin pole, and the connections are made by using a set of power tongs that remain hanging by cable at the height of the work area. The tong may also be attached to a tong arm fixed to the basket.

Operating in this manner requires specialized people, usually consisting of a foreman and three or four people per shift. The space in the snubbing basket is usually very limited and unstable, which magnifies the hazards associated with the manipulation of pipe, elevators and power tongs.

ODS International and Rogers Oil Tools (ROT) have developed a patented power tong built specifically for snubbing and well control applications (Figure 1). It is the only tong designed to ride the jack incorporated with a swinging basket.

No tong pole and no pushing or pulling of the tong on and off the pipe is necessary, which eliminates nagging injuries (broken or mashed fingers, twisted or strained backs, shoulder damage) and significantly improves the efficiency of the operation.

ODS-ROT can provide different models, either slip or jack-mounted (Figure 2), providing the choice of eliminating personnel in the snubbing basket by utilizing the remote operation option.

The jack head tong carries the provision of having a three-section cage plate system that can be removed to allow the jack head tong to be open for full wellbore capabilities, matching the BOP’s bore. This is the fastest and safest way to trip pipe with a snubbing unit.

Snubbing is an old technique with relatively little innovation over the past several years. The hazards associated with this type of operations still must be considered when seeking to eliminate risks.

The snubbing power tong introduced in this article is a viable alternative, making operations safer by eliminating movement of the tong on and off the pipe. This eliminates nagging injuries and increases the operational efficiency, which ultimately impacts the overall costs of well servicing programs in benefit of operator and drilling contractors.

If I’m working day shift, I usually get up around 5.15am and head down to the camp kitchen. It’s always a rush in the mornings, so I have about 15 minutes to get as much food into me as possible. Eggs and bacon, lumberjack type stuff.

At 6am the crew truck shows up at camp, and we pile in and head off for our 6.30am safety meeting. Once that’s done we head out onto the rig to find our cross-shifts, get a brief run down on whatever they’re working on and pick up where they left off.

Daily duties depend entirely on what the rig is doing. If we’re drilling, the days tend to be a bit more relaxed – keep an eye on the motors, the gens, the pumps, and head up to the drill floor whenever another pipe has to be connected to the drill string.

If there’s problems down hole, it means we might have to trip – pull all the pipe out of the hole and fix the problem. A drill bit might need to be changed, or we may need to adjust the setting on the tool that steers the drill bit. Tripping can take a lot out of you. It’s a routine of extreme physical exertion followed by brief periods of rest, doing the same thing over and over until all the pipe is out of the hole and the problem can be fixed. When it is, it’s the same thing again in reverse order until the bit is back on bottom and we can drill again.

At 6.30pm, the other crew shows up for their safety meeting, and by 7.15pm we’re usually headed back to camp. A quick shower and a shave, dinner in the kitchen, and then the gym or a book until bed time. There’s all sorts of operations that might be happening on any given day, so it’s pretty difficult to describe a ‘typical’ day.There"s been a lot of talk lately about people wanting work/life balance. Does your job provide that?

Yikes – this is a question I don’t like thinking about. We work out of town on a two-and-one rotation – that is, 14 days on followed by seven days off. That means if I were to work a full year, I’d spend eight months away at work, and four at home. It’s tough. Because this line of work requires a lot of traveling, I often go months on end without seeing certain friends or family members, it makes it hard to have a normal social life. It’s strange, a rig hand spends all his time at work wanting his hitch to end so he can get home, but when he does it seems like your week off goes by twice as fast. I"ve managed to alienate a lot of friends and girlfriends working where I work.

So no, oil rigs don’t provide what you’d call a healthy balance of work and life. I had a cousin tell me once that you sell your soul to make money in the oil field, and sometimes it seems like he was right.What"s the craziest/most unexpected thing that"s ever happened to you while working?

This is a hard one to pin down. Take a handful of strange people, put them in the middle of nowhere and have them operate a giant machine, and weird things happen. We’ve had bears chase workers across the lease, planes skidding sideways down snow-packed airstrips, helicopters losing altitude, and too many cases of people coming very close to getting seriously hurt or killed. But it’s not all bad – the northern lights can be spectacular if you’re working in the arctic, and Alberta sunrises are always nice at the end of a long shift.What makes for a really good day at work?

The weather, the work and the people. You spend just about all of your time working closely with your crewmates, so if you’re lucky, it gets to be like a family after a while. If the temperature is just cool enough so you don’t sweat, tripping pipe out of the hole all day with your brothers is just about as good as working on an oil rig can get. If everyone knows what they’re doing and gets into a groove, the whole thing clicks and the crew operates like a well-oiled machine. After a good trip you can leave the rig with a sense of accomplishment, puff your chest out a bit when the other crew comes and sees how fast you were. On days like that, it’s always nice to head down to a river after work, get a bon fire going and have a beer or two with the guys. But depending on which oil company you’re working for, alcohol of any type might be contraband, so beer is out of the question. Which can kind of put a damper on things when you’ve worked all day in the heat.What"s your annual salary? Do you get benefits?

Most rig hands are paid hourly, only the brass gets salary. We’re paid quite well though, and working 84 hours a week makes for some nice overtime. A derrick hand gets a base wage of $37/hour. We also get a living allowance, $50 a day if we’re living in camp, $140 a day if we have to find our own accommodations.

Depending on how much of the year a rig spends working (or how much a rig hand wants to work, if the industry is busy), a guy can make anywhere from $70,000 a year up to a couple hundred thousand. I’m still relatively low on the food chain in the grand scheme of things, but I’m fortunate enough to work steady. A derrick hand working year round typically makes over six figures.

The benefits vary from company to company, but they tend to be quite good. It’s a rough line of work, and companies need to treat their guys pretty well or the guys will jump ship to another company. I’m lucky – the company I work for treats us right.What"s the biggest mistake you"ve ever made on the job?

1 Do not, ever, under any circumstances, drop an object down the hole. Hammers, wrenches, chains, and pretty much anything made of hardened metal can destroy a drill bit, and drill bits can be quite pricy. The wells we drill cost millions of dollars, and pulling the pipe and going fishing for a tool down hole can cost into the hundreds of thousands, and take days to do.

2 Do not, ever, under any circumstances, hurt someone. This one should need no explaining, but it’s surprisingly easy to do something that could put someone else in danger without even realizing it.

3 Don’t get hurt. This is a touchy one, but unfortunately it’s still true. Getting hurt doesn’t just ruin your week/year/life, it costs a lot of people a lot of money. Settlements might have to be paid, bonuses are lost, investigations have to happen, and someone must be held accountable.. Sometimes entire rig crews will get drug tested after an accident. They test us to ensure drugs or alcohol didn’t contribute to the cause of the accident, but it comes across like a punishment: “If you get hurt, you might cost someone else their job.” Unfortunately, it causes a lot of guys to sweep injuries under the rug. It doesn’t happen so much at my company, but it’s depressingly common in the industry.

Doing any one of the three things above is liable to give a guy a reputation, and a reputation can follow a guy from rig to rig, company to company. It’s a relatively tight knit industry and word travels fast. It’s not uncommon to find yourself working beside someone you heard about years ago on a different rig, if he’s got that reputation following him … I’ve managed to stay rep-free to date, and hopefully I can keep it that way.Here are some highlights from Tyson"s Q&A session in the comments below:Would you consider flying into space to blow up an asteroid if you had Liv Tyler to sweeten the deal?This is a no-brainer: Yes, definitely.

We actually use Armageddon as a safety training video.Does the environmental threat posed by our dependence on oil as an energy source worry you?To be honest, it"s something I don"t put too much thought into anymore. Obviously oil dependency is not a good thing for this planet, but me putting my foot down and quitting my job would do about as much good as yelling at an asteroid about to destroy the planet. If I were to go, there"d be someone there to take my place within the hour.

That"s not to say that I don"t try and live responsibly at home though.. I take transit and recycle as much as the next person, if not more.Harsh conditions, a nice salary, a real man"s mans job.

Oh, and thanks for the fuel that we all use in our day to day lives.Hey! No problem. I can"t quite take all the credit for the gas in your tank, but I"ll be selfish this one time.

To be honest, most riggers don"t join the profession as much as they do, just... end up there. It"s hard work, but it"s fast money, and a lot of guys that only intended to do it temporarily end up sticking around once they get used to the pay cheques. That"s what happened to me anyways...

For qualifications, you must have your First Aid and WHMIS tickets, and a course in Hydrogen Sulfide safety. It"s deadly stuff, poisonous and explosive, and odorless in higher concentrations.I"ve heard that drugs like methamphetamine are a problem among oil workers, especially those that work overnight.

(p.s. thank you for the gas in my tank! i know it"s a tough job, and we all appreciate the work you do!)Yikes. Stimulants yes, but methamphetamine, not so much. Oil companies and drilling contractors are becoming more and more strict in their drug testing practices, and a slowdown in the industry (like we"re having now) is a great time for companies to weed out the riff raff. That being said, every oil worker knows that cocaine is out of your system in 2 days, whereas weed can stick around for up to a month and a half. A lot of guys have to get wise for a couple days before a drug test.

I stick to coffee. Night shift tonight, and I"m posting comments on the Guardian when I should be sleeping...Nightshift in the winter. Do you get to see the sun?What is the town of Ft. McMurray like?Fort Mcmurray is a town I"ve managed to steer clear of for several years now. And Mike is right: the majority of the bitumen around Fort Mac is mined rather than drilled.

The project I"m on right now is about an hour and a half south of there, near Conklin AB. We"re accessing the same bitumen, but using a less invasive technique. Rather than mine the bitumen, pairs of wells are drilled into the formation -- one to inject steam and make the oil easier to pump, and one to suck up the now much-less-viscous oil.

If it answers your question at all, the camp where we"re currently living holds about 2000 people, has 2 enormous cafeterias, 5 gyms, pool tables, 1 theatre, and apparently there"s a racquetball court here somewhere too. In terms of work camps, this one"s the creme de la creme.Have you ever worked on a drilling rig where it was necessary to throw the blowout preventors (BOPs)?I have. Actually, just last month we were working in Saskatchewan and had to shut the well in when we drilled into a pressurized water formation. An "Artesian Well," is what they"re called if I"m not mistaken. Luckily there was no sour gas in the area, so there was no chance of burning the rig down if it blew out.

Mike: The old timers still talk about that blowout in Drayton Valley, 80 meters from surface with no BOP"s? I remember hearing about a derrick hand getting killed during that blowout, the escape pods we have hanging from the monkey board now all have D.V Safety stamped across the side as a reminder...How many guys on a team? Do you get lunch?Anywhere from 5 to 9 people on a crew, and usually 3 crews per rig. The pecking order on my rig is as follows:

Usually we"ll cycle out for lunch. One person eats at a time so the work doesn"t have to stop.It seems to me that we"re increasingly polarised between those who want no development at all, and those who want to go full steam ahead, whatever the cost and impact.

Do you think the "average" Canadian is well-informed enough to form a credible opinion about our extractive industries?This is a tough one. It"s surprisingly difficult to get a balanced viewpoint on Canadian oil and gas by reading any one paper, so I would have to say no, an average Canadian most likely does not see both sides of the story.

Depending on what province you"re in and what paper you"re reading, you could see two diametrically opposed viewpoints on the same issue. Case and point: I read the news in both Vancouver (where I live), and Edmonton (where I spend a lot of time for work). The Northern Gateway pipeline is pretty big news right now, but judging by how it"s painted by the news in BC and Alberta, it sounds like two different pipelines on two completely different planets.One of my female friends used to be a engineer of some description (it involved gas, but I cannot remember the details). Are there many females involved in the profession today?I apologize, I"m kind of picking them off in no particular order. Women are becoming more and more prevalent in the industry, though it"s still far from what you"d call a "normal" work place. It"s rare to see one working on the rig itself, but not unheard of.

On-site medic (EMT or EMR) is a fairly common job for women to hold, and more and more often you"ll see female petroleum engineers.How do people react when they find out what you do for a living? With the energy debate so heated and polarized, do you ever experience any negative reactions?

What is the biggest misconception about people in your line of work? What"s the actual truth?Again, the answer to this one varies depending on where I am at the time. A lot of people look down their noses at oil workers, the whole white-collar vs. blue collar thing. Where I"m from, a lot of people see The Rigs as a copout, a place where drop outs and ex-cons can go to afford payments on a jacked up truck. "Rig Pig" is a fairly common term... Of course some of the guys out here are pretty rough around the edges, but those are the only ones people notice in the city. I work with plenty of people that are completely normal, functioning human beings. Wife and kids, mini-van... Not the type you would see in the street and label a Rig Pig.

Occasionally you"ll meet a militant environmentalist who will waste no time in insulting you for your work. Which is fine -- everyone is passionate about something. But until those people are prepared to give up living with petroleum products, they should think twice about ridiculing someone for trying to make a living. Oil rigs exist because people drive cars, not the other way around. If people stopped driving, the rigs would cease to exist. But they"re a very hate-able face to the problem of oil dependancy.

The Attorneys at Spurgeon Law Firm know what it’s like to spend countless hours tripping pipe on a drilling rig. Stephen and Sam both have experience working on drilling rigs where they have roughnecked on Kelly and rotary drilling rigs.

Running in the hole or pulling out of the hole (aka tripping pipe) is one of the most labor intensive job tasks a worker will engage in while on a drilling rig. Long hours of throwing the slips in, breaking or making connections, and racking back stands of pipe in the derrick is mentally and physically exhausting whereby your brain will start to populate abnormal thoughts. Your mind will start to drift due to fatigue and exhaustion and thus cause you to lose focus on the job at hand. Because of this, people are more susceptible of making mistakes, which in turn will cause injury to themselves or someone else. This is why it is imperative that companies have adequate personnel on the job and to allow that personnel to take breaks as needed. Your safety should be priority and always put your health first and the company’s profit second.

All oilfield workers have the right to work in a safe environment. The oilfield is governed by rules, laws, and guidelines to keep workers safe. However, these rules and laws are not always followed and often lead to serious injury. If you have sustained injuries in the oilfield contact our experienced oilfield lawyers at 318-224-2222. Attorneys, Stephen and Sam, have both worked in the oilfield and know the ins and outs. Prior to becoming an attorney, Stephen worked offshore as a Petroleum Engineer gaining valuable experience which he uses to get his clients maximum compensation. Their experience can make the difference when it comes to getting the payment you deserve. Contact Spurgeon Law Firm today for a free consultation.

Canadian drilling rigs meet some of the highest regulatory and safety standards in the world. It"s a dynamic and exciting community to build a career in.

Canada’s drilling fleet is always changing to incorporate new technology and meet market demand. Most noticeably, the Canadian drilling fleet is growing in numbers. The fleet has 40% more rigs than it did 15 years ago. Today, the rig fleet offers just over 600 rigs.

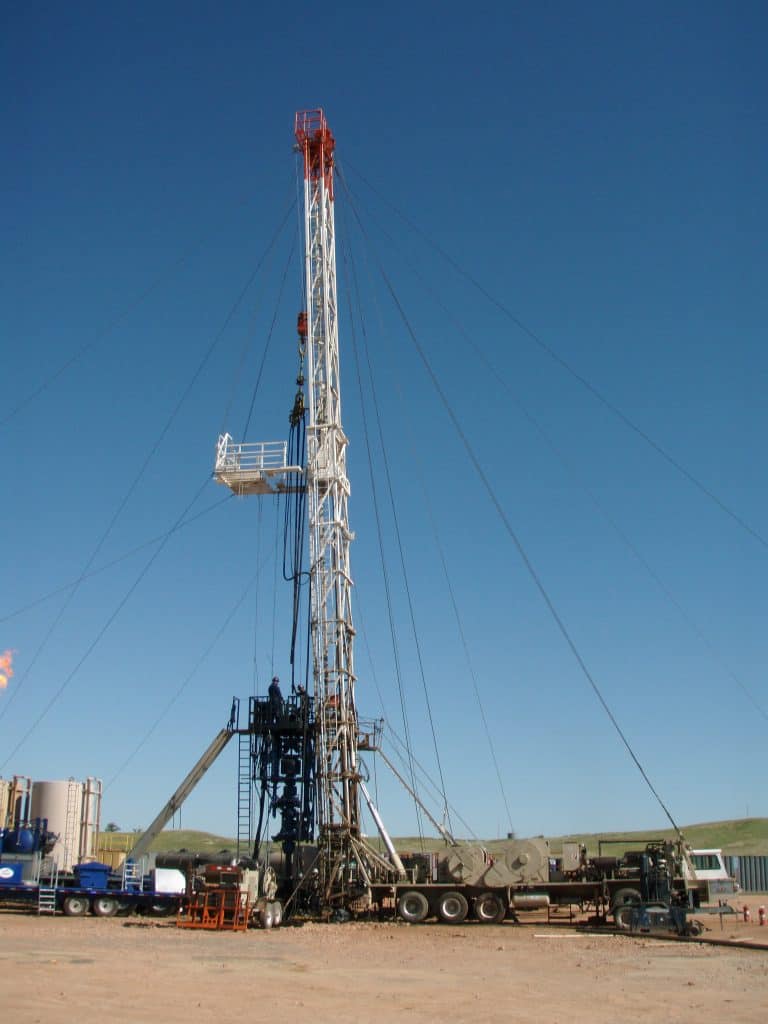

For the most part, a rig is a rig is a rig. For example, all rigs have a derrick (the mast-like structure that holds the pipe to be lowered into the well bore) a catwalk that holds the drill pipe, a rig floor where floorhands handle the drill pipe, a drawworks which is the machinery that hoists and lowers pipe and a blowout preventor that enables a driller to control well pressure.

But different size rigs are used depending on the drilling target formation. Oil formations tend to be deeper than gas formations. When investors are most interested in producing oil, large rigs are in high demand. When the market prefers gas production, small rigs are in demand. Western Canada has plenty of both gas and oil, and activity cycles back and forth between preferences of one over the other.

Drilling rigs come in three sizes: singles, doubles and triples. These categories refer to how many lengths of pipe can stand in the rig’s derrick. On a single, the derrick holds one length of pipe. A double holds two, and a triple holds three.

A tall derrick isn’t necessary to drill deeper. If more pipe is needed to drill deeper, a single section of pipe is hoisted to the rig floor and added to the drill string. But sometimes the entire drill string needs to be pulled out of the hole (to change the drill bit, for instance). A derrick that holds multiple lengths of pipe comes in handy and helps the crew to complete this evolution quickly.

A crew working on a triple is able to pull three lengths of pipe out of the hole before unscrewing the pipe. The Derrickman, working from the monkeyboard, sets the ‘stand’ of pipe in the derrick. Then the crew pulls up the next three joints of pipe. This evolution is called ‘tripping’.

The larger derrick is efficient to drill deep wells but isn’t necessary for shallow wells. Single rigs drill wells that are around 1 to 2 kilometres deep. These wells usually access gas basins. Single rigs and their crews change drilling locations often, sometimes every day or every other day.

Doubles and triples are larger rigs with bigger substructures and taller derricks. These rigs drill between 3 and 6 kilometres into the earth and might be at the same location for several months to complete deep drilling operations.

Singles, doubles and triples refer to conventional rig categories. Additional new categories of rigs have introduced different ways of handling pipe. For instance, some companies run coil-tubing rigs that stream tubing from a large reel instead of using drill pipe, or automated drilling rigs that are outfitted with a pipe-handling arm that raises the pipe into the derrick, eliminating the need for a derrickhand to work from the monkeyboard.

Through the 1990s, rig activity focused evenly on the two commodities. Then in 1998, there was a shift: gas wells began to make up the bulk of drilling activity. Through the early 2000s, rig activity increased year over year, but gas wells—which are shallower and can be drilled faster—far outstripped the increase in oil wells. Between 2001 and 2006, oil wells made up about 25% of rig activity, and gas wells 75%.

The drilling industry reacted to this demand by expanding the fleet. In 2007, the rig fleet grew faster than it ever it had before: 49 rigs were added. Most of these new rigs were the smaller ones best suited for gas drilling. Then in 2008, natural gas was on the market in abundance, and the stock market price of natural gas started to fall. Investors pulled back on gas drilling. In 2010, industry was back to an even split between gas wells and oil wells.

And then the turn-around happened: oil drilling overtook gas drilling in western Canada. In 2011, 61% of the wells drilled were seeking an oil formation, versus the 39% seeking gas. Today’s market continues to favour large rigs that can reach deep oil formations. There also is increased interest in accessing these formations at an angle: rig crews drill a well bore that curves toward a drilling target. Drilling rig contractors have been adding equipment in 2013. Unlike 2007"s fleet expansion, these rigs will be the larger, heavier rigs, primed for oil drilling.

Independent producers and operators ramping up shale exploration and development programs are pushing the limits of conventional drilling equipment. Whether they are drilling multiple long-lateral horizontal wells from single pads, testing new bits and mud motors to boost penetration rates, or deploying next-generation rig floor and automation systems to slash “spud to sales” times, independents and their service company partners continue to find ways to improve resource play economics and crack the unconventional drilling frontier wide open.

Goodrich Petroleum is a case in point. Over the past two years, the company has transitioned from vertical Cotton Valley wells to horizontal wells in the Cotton Valley and the underlying Haynesville Shale. To unlock the shale’s vast potential, the company worked with its partners and service providers to discover the right casing points and to choose bottom hole assemblies that could build at sufficient rates to maximize lateral lengths, reports Clarke Denney, the company’s vice president of drilling. He notes that in the Haynesville Shale, Goodrich is utilizing robust directional equipment and mud cooling units to drill laterals at vertical depths of 15,000 feet, where circulating temperatures can reach upward of 340 degrees Fahrenheit.

The company’s efforts have paid off. By shifting focus from vertical Cotton Valley wells to the Haynesville, Goodrich reduced its overall proved developed finding and development costs from $3.21 an Mcf of gas equivalent to $2.38 an Mcfe from 2009 to 2010.

With oil prices trading much higher than natural gas on a Btu equivalent basis, Goodrich also is targeting the oil window of the Eagle Ford Shale. In South Texas, the company is drilling wells with vertical depths between 6,500 and 8,500 feet and lateral lengths from 4,500 to 6,000 feet. Although these wells take skill, time, and money to plan and construct, company officials say they believe they can achieve 50 plus percent returns on investment.

Drilling wells in either play requires rigs with the right equipment, says Denney. He says top drives are important because they allow pumping and rotating the drill string while coming out of the hole, which is necessary at times for hole cleaning. This reduces drag and the chance of getting stuck. Top drives also maximize directional drilling performance.

Drawworks that can deliver at least 1,500 horsepower are also key, Denney adds. “We believe in high horsepower,” he stresses. “A 1,500-horsepower rig carries a premium over a 1,000-horsepower rig, but it speeds trips and puts less strain on the equipment. We get our money’s worth.”

Just as important as the drawworks and top drive is having powerful mud pumps on the rig, Denney says. “In the Eagle Ford, we would prefer to have at least 1,600-horsepower pumps, especially when drilling long laterals,” he relates. “That horsepower is needed for mud hydraulics to keep the hole clean, and to drive the downhole motor and other equipment. We have achieved up to 6,000-foot laterals to date, and we are targeting 9,000-foot long laterals in the near future.”

In many cases, it makes sense for the rig to have the ability to skid, Denney says. He explains that drilling multiple horizontal well bores on one pad reduces construction costs and rig transit times. “In the Eagle Ford, if we can skid, our drilling costs can be reduced as much as $500,000 a well,” he says.

Goodrich Petroleum is far from the only company that needs “high-spec” rigs with powerful top drives, hoisting systems and pumps. According to industry sources, rigs with larger (+1,000) horsepower ratings account for an estimated 60 percent of the active rig fleet. Moreover, rigs with at least 1,000 horsepower account for nine of every 10 rigs that are under construction or planned for the near future.

With its operational focus transitioning from the Cotton Valley trend to the Haynesville Shale, and more recently to the Eagle Ford Shale, Goodrich Petroleum is achieving consistent production and reserve growth through horizontal drilling with high-spec land rigs and advanced downhole tools. Even during the economic recession of 2009, the company increased average net daily production 24 percent and proved reserves 5 percent. Over the past four years, it has more than doubled its daily production while expanding its reserves 30 percent.

Trent Latshaw, the founder and head of Latshaw Drilling in Tulsa, can verify that the demand for 1,000-2,000 horsepower rigs is high. He says the company’s fleet, which includes 15 rigs within that range, has 100 percent utilization. In fact, Latshaw reports that the only unused rig his company has on the books is a new, 1,700-horsepower diesel electric that is still under construction.

Many of today’s high-spec rigs have closed-loop mud systems, Latshaw notes. “Closed-loop mud systems do away with the need for a reserve pit,” he says. “The systems also processes drilling fluid more efficiently. They are able to take more solids from the drilling fluid, which enables more fluid to be reused and makes the solids dryer and easier to dispose of. That becomes very important when dealing with oil-based mud, which often is used in horizontal wells.”

Latshaw encourages operators to consider using high-horsepower rigs when the class they want is difficult to obtain. “We consider our 2,000-horsepower rig to be identical to our 1,500-horsepower rigs, except for the drawworks size and the mast/substructure capacity,” he says. “The 2,000-horsepower rigs have the same footprint and move as fast as the 1,500-horsepower units, and for all practical purposes, the day rates are the same.”

He also says diesel-electric SCR rigs are comparable to AC rigs. “They have the same top drives, the same mud pumps, the same mud systems, the same engines, and the same blowout preventers,” he reports. “From the customers’ perspective, they drill wells as fast as AC rigs.”

In reference to safety, Latshaw says people matter more than technology. “You can try to design a piece of equipment that is accident proof, but safety comes down to the people on the rig floor and what their mindsets are,” he insists. “We are putting more money into training, beefing up our safety department, and having more safety coaches go around the rigs to work with the hands.”

He points out that many rigs, including several of Latshaw Drilling’s units, use automated iron roughnecks to improve safety. “Those are expensive, high-maintenance pieces of equipment,” he says. “We decided to take some of them off our rigs, then track closely to see if we had more finger and hand accidents on the rigs using manual tongs and a drill pipe spinner versus the rigs that had iron roughnecks. We have not seen a difference.”

For Joe Hudson, the president of Nabors Drilling USA, the future looks bright. “We have at least 103 AC rigs deployed at this point,” he reports. “We are in the process of building 25 more, and we always are looking for opportunities to expand further, be it in the Bakken, the Mid-Continent, West Texas, the Eagle Ford, or the Marcellus.”

Hudson says the new rigs include larger pumps, AC top drives, and tubular handling tools such as automatic catwalks and floor wrenches. “With the automatic catwalk, there is no need for a rig hand to pick pipe off the catwalks, pull it up with a hoist, and drag it to the rig floor,” he says. “Instead, the catwalk picks up pipe and elevates it to the rig floor. No one is touching the pipe or rolling pipe onto the catwalk, which keeps people away from tubulars, reducing the risk of pinch-point injuries.”

The floor wrench also improves safety, Hudson says. “Normally, a roughneck would make up pipe with manual tongs,” he notes. “The floor wrench engages the pipe and makes it up with an automatic tool, which keeps his hands safe. It also increases pipe longevity by reducing damage from the manual tongs.”

Hudson says statistics and feedback show the new equipment reduces accidents. “There is an efficiency gain as well,” he adds. “With this equipment, we have improved control and improved well hydraulics, which results in faster well times.”

The rigs also employ advanced software. “With conventional rigs, the driller would drill ahead with a hand on the brake handle. He had only basic drilling information available to him, and his skill and his experience with the area dictated his ability to drill the well,” Hudson recalls. “Today, the software associated with smart drilling systems allows him to drill the well with a better understanding of the factors that influence drilling performance, such as delta P, hydraulic horsepower, weight on bit and rate of penetration. That translates to a faster rate of penetration.”

To ensure that its employees work as safely and efficiently as possible, Nabors has fully functional training rigs in Williston, N.D., Casper, Wy., and Tyler, Tx., where it trains personnel with no previous experience, Hudson reports. He adds that the company carefully defines the training and competency individuals need to be promoted.

The newest generation of high-spec land rigs purpose-built for horizontal drilling in unconventional resource plays features integrated subsystems to automate key processes such as pipe handling. Automated catwalks and floor wrenches not only increase operating efficiency, but also improve rig floor safety and extend pipe longevity by reducing handling damage.

Nabors’ focus on training and its preference for promoting from within help it maintain a skilled workforce, Hudson indicates. “When the market is expanding, we are able to identify promising, trained personnel within the company, give them a career path, and move them through the system. That helps with retention,” he explains.

When downturns do occur, Nabors tries to keep competent people and trainers on staff, Hudson says. By doing so during the last economic downturn, he says the company managed to go from 92 rigs in fall 2009 to 190 rigs today without compromising its personnel or safety standards.

Regardless of the market condition, Hudson says it is vital to design rigs for specific areas. “Every area is unique,” he says. “Carrying the top drive in the mast is a great way to reduce the number of loads needed, but in areas where road weights are critical, other approaches have to be adopted.”

To illustrate regional developments, Hudson points to Nabors’ B-series rigs, which were designed to accommodate pad drilling in the Bakken Shale. “We built a box-on-box substructure because we can close in that substructure, which makes it easier to winterize,” Hudson says. “Also, the way we can rotate the substructure lets the company conduct completion and production-related operations on one well while we are drilling another on the same location.”

In the Rocky Mountains, mobility is vital, says Patrick Hladky, a principal and contract manager for Rockies-focused Cyclone Drilling. “It is important to optimize mobility because we cover such a large area,” he says.

Dealing with cold weather is also important, he observes. “We protect the rig floor from wind by putting the dog house and wind walls around it, then put heaters on the floor,” he says.

Like other contractors, Cyclone is expanding its fleet. “We built five rigs in 2010 and we are scheduled to build four more in 2011,” Hladky details. “They all have 1,600-horsepower pumps, with 270- and 500-ton AC top drives.”

Hladky says Cyclone tries to keep the rigs’ designs simple. “We engineer all the rigs similarly,” he adds. “Even if they are different sizes or different applications, the basics are all the same. That lets employees move from rig to rig efficiently and safely.”

The company also tries to put equipment in convenient places. “For example, rather than putting the oil storage tanks in a separate building, we put them with the engines,” Hladky says. “That is where our hands will use them.”

In the Bakken Shale, Continental Resources is drilling four-well pads. By drilling and casing all four surface holes, then all four intermediate holes and finally all four laterals, the company reduces the number of times it needs to change the mud type and drill pipe. Continental says this process reduces drilling costs as much as 10 percent.

Like the other drilling contractors, Hladky stresses the importance of good people. “A high-spec rig is nothing without good people,” he declares. “We are drilling with mechanical rigs built in the 1980s and 1990s with good people right next to and as efficiently as high-spec rigs.

“We have a young workforce, especially in the Williston Basin, which has grown so fast a lot of the people are new to their jobs,” Hladky observes. “That means we need to do more training. We have put night supervisors on location so the hands can get help and training at night.”

Cyclone Drilling also trains hands on site through a mobile training center, Hladky reports. He adds that the company hired Afterburner, a leadership consultant, to help its supervisors and managers promote safety and efficiency. “We are seeing results from that already,” he reports, noting that Afterburner emphasizes focusing leaders on teaching, rather than policing.

The combination of experience and training has paid off. “We already have seen efficiency gains from when we were first ramping up a year ago,” Hladky says. “The longer the cycle becomes, the more gains we will see.”

Pad drilling has a long and successful history in the Rockies and has spread to basins across the United States, Hladky points out. “It creates efficiencies for drilling times and costs, as well as environmental benefits. The pad is only disturbing the land in one area, even though it allows several wells to be drilled, completed and produced from that one surface site.”

Cyclone skids its rigs with hydraulic feet rather than rails because rigs can get slightly off target each time they move from one well to the next. “If you are on a rail system, the error is difficult to deal with. A walking rig can move in any direction needed to position exactly over the well bore,” he says.

On pads with several gas wells, Hladky says the operator can do simultaneous operations. “As we are drilling one well, he can set up his frac crews on a different location and pipe fluids to the pad to complete a well or put wells on production. That lets the operator get a return on the investment without waiting for the entire pad to be completed.”

On other pads, Hladky says Cyclone advocates batch drilling. “In this case, we drill all of the well’s surface holes as a batch, then drill all of the intermediate sections, and conclude with drilling all the laterals,” he says. “Instead of swapping mud systems several times for each well, we can use the same mud system and tools over and over.”

In addition to reducing the amount of time directional drilling companies need to be on site, that approach makes life easier for the crew. “They are not changing hole sizes or changing well parameters,” Hladky explains. “The repetition creates efficiencies. More than likely, your last well will be faster than your first one.

Continental Resources has used batch drilling to great effect in the Bakken, reports Glenn Cox, the company’s northern drilling manager. He says the company is using four-well pads, with two wells on each pad targeting the Middle Bakken interval and two targeting the Three Forks formation.

“We started looking at these pads primarily from a surface usage viewpoint,” Cox says. “Since the terrain in North Dakota can be difficult, we wanted to reduce the number of pads, handling facilities, power lines, and pipelines we had to build. As we dug into the process, we began to ask if we would save any money beyond the cost of building the location and moving the rigs. The batch process provided the cost savings that gave us the impetus to keep working on the project.”

To use pad drilling to full effect, Continental had to overcome a hurdle: North Dakota’s setback laws. “Setbacks from the lease line were normally 500 feet,” Cox recalls. “When we drill a well, the curve radius is 450 feet. The drilling location is roughly 150-200 feet from the section line, so once we drill the curve and set the casing, we have achieved the required setback.”

The problem was that the 500-foot setback made it difficult to drill into the adjacent section. “To achieve the setback there, I would have needed to drill 650-700 feet. That means we would have had to drill the curve down, trip out to get a different motor, and go back in to finish the last 200-300 feet before setting casing,” he details.

In response, Continental asked the North Dakota Industrial Commission for a variance to the setback rules that would allow it to drill into the adjacent spacing unit. “The state eventually granted the 200-foot setback to the entire industry,” Cox says. “That probably has resulted in noticeable reserves recoverable for everybody working the Bakken/Three Forks.”

As of mid-March, Continental had drilled seven pads. The batch drilling process and pad construction savings reduce the cost of drilling each well as much as 10 percent, enough to save the company $2.5 million for each pad, Cox says. He adds that the process reduces surface impacts by as much as 75 percent.

To explain the process’s economic and environmental benefits to investors, Continental dubbed it ECO-Pad® and produced a video, which is now available on its website. “It’s been amazing how many people have watched the video and asked to show it to others,” says Brian Engel, Continental’s vice president of public affairs. “The walking rig is something almost no one has seen before, especially in the investor community.”

As drilling contractors build their fleets and train employees, equipment manufacturers are coming up with better ways to design and manufacture components. These include downhole motor manufacturers. “We are dedicating significant resources toward boosting overall motor performance, with specific focus on increased power and equipment reliability,” says Mpact Downhole Motors Vice President David Stuart.

From the field to the office, equipment manufacturers are working with operators and service companies to improve drilling efficiency. For example, they are developing mud motors that can support higher rates of penetration without sacrificing reliability, as well as solids control equipment that offers greater efficiency and flexibility.

To maximize reliability, Stuart says manufacturers are designing downhole motors that can operate under increasingly higher loads. In addition, they must ensure motors are designed to be compatible with ever-changing drilling conditions. “Drilling motors have to be designed and calibrated for each specific application to compensate for changes in temperature and other downhole conditions, which will cause the components to expand and contract during drilling,” Stuart remarks.

Premium elastomers are playing a key role in manufacturers’ efforts to improve reliability, Stuart says, explaining that the new-age materials also provide higher differential pressure and torque.

Stronger motor transmissions and bearing assemblies also are on the industry’s drawing boards, Stuart says. “We have worked with key suppliers to develop new thrust bearing designs to increase load capacity,” he says. “The higher capacity improves reliability and offers increased weight-on-bit, which enables higher penetration rates.”

Even with the best motors, Stuart advises operators to stay within the motors’ optimum operating parameters. “The drilling motor is similar to an engine in a car,” Stuart says. “You can run it at the red line on the tachometer and go really, really fast for a short time, but if you run that hard for a long time, the engine is going to have problems.”

The ideal operating range varies with motor sizes and configurations, Stuart says. “Experience goes a long way in determining the right range, and it comes not only from the drilling motor provider, but also from the service companies and operators. Collaboration among the three is important for efficient drilling operations,” he advises.

The combination of technology and experience has paid off, Stuart says. “Our motor run success ratio has improved continuously. It is now above 98 percent,” he reports.

The mean time between failures (MTBF) also has improved, Stuart says. “At our company, the MTBF in 2008 was 3,069 hours,” he recalls. “In 2010, it was 3,509 hours, a 13 percent improvement. We are extremely proud of that, especially given that equipment continues to be pushed harder and harder.”

No matter how hard operators push their equipment, the fundamental goal of fluids handling systems remains the same: keeping the drilling mud in good condition. But with the cost of drilling fluid additives and oil-based mud on the rise, KEM-TRON Technologies President Michael Rai Anderson says it is becoming increasingly beneficial to manage mud through solids control treatment systems. “Fluids handling companies have responded,” Anderson states. “We are finding ways to remove contaminants from the drilling mud while recovering as much usable material as possible.”

Drilling contractors are expanding their fleets to accommodate growing demand for high-horsepower land rigs equipped with powerful mud pumps, heavy-duty drawworks, closed-loop mud systems, automated rig floor equipment and ‘smart’ data management systems. As with this 1,500-horsepower electric rig, these new high-spec units often are fitted with top drives to rotate the drill string to optimize drilling efficiency and reduce the chance of pipe sticking while coming out of long horizontal laterals.

Anderson says several developments will help with that effort, including a new shaker that enables the operator to vary the gravitational force imparted between three and eight gravities. “Being able to fine-tune the shaker to the solids load will help operators get a better cut and reduce screen consumption,” Anderson says. “High G-forces can be used during top-hole drilling, when solids loading is high, and lower G-forces can be used when solids loading drops. This improves residence time and ultimately solids cut.”

To maximize performance and cost effectiveness, the shaker uses a passive-vibrator technology, Anderson says. “The system uses gears instead of rotating unbalanced weights,” he outlines. “The passive vibrator assembly reduces the complexity of electrical systems needed to create the variable frequency, enhancing system control and maintenance.”

Vertical cutting dryer technology also is improving, Anderson indicates. “We are working on new chemical injection techniques to break the surface tension between oil-based drilling fluids and the cuttings. This lowers the energy required to separate the fluid from the cuttings.”

A typical cuttings dryer can reduce the amount of drilling fluid on the cuttings from 15 percent to 5 percent, Anderson says. “With chemical injection enhancement, we may be able to bring that down to 1 percent,” he reports.

According to Anderson, the new chemical injection techniques are part of a growing trend: When it comes to environmental issues, oil and gas companies are going beyond regulatory requirements. Anderson goes on to state, “This means that the technology is evolving and new products will enter the market, making solids control and waste management more efficient and cost effective.”

To help centrifuges separate water and cuttings, operators often add coagulants and flocculants to the drilling fluid before it reaches the centrifuge, Anderson notes. Ideally, the coagulant neutralizes the suspended solids’ electrical charge. Once that happens, the flocculants’ electrical charge will attract the solids and bind them, which will keep them from mixing with the water in the centrifuge. This makes the centrifuge more effective, Anderson explains.

To work well, the coagulants and flocculants need to be conditioned, or “made down.” Conditioning involves mixing a concentrated form of the polymers with water, then waiting for them to uncoil, Anderson says. If this process is done poorly, he says the coagulants and flocculants will go to waste and the centrifuge will fail to separate the water and suspended solids to the degree intended.

“Getting hydration right can be tricky,” Anderson says. “The coagulants and flocculants typically used to dewater drilling fluid have long, fragile chains, so they are sensitive to high mechanical shear forces and temperatures. Low pressure is also a concern; it increases residence times.”

Because hydration is the most important aspect of maximizing polymer effectiveness, Anderson says his company has developed an affordable, modular chemical injection system that uses automation to closely control hydration. “The system controls the polymer’s flow rate, water pressure, polymer mixing, polymer residence time within the manifold, and the temperature at which the polymer is being conditioned,” Anderson reports. He adds that the retrofits needed to install the system on an existing centrifuge are minimal.

In addition to expanding the capabilities of existing technologies, Anderson says manufacturers and end-users are scrutinizing almost every piece of solids control equipment on a quest for stronger, lighter and smaller equipment that can perform heavyweight tasks. This requires more than product engineering, it requires value engineering. “In value engineering, companies critically examine the equipment configuration, operating philosophy, raw material selection and fabrication practices,” Anderson says.

That approach is being applied to centrifuges, Anderson reports. “About 50 percent of a centrifuge’s cost is in the rotating assembly,” he observes. “We are looking at ways to lower that cost and improve the quality by using different materials and improving the geometry of the parts to reduce the need for time-consuming and expensive machining.”

Improved designs likely will reduce large bowl centrifuge costs 10-15 percent, enough to temporarily offset the ever-increasing cost of raw materials such as stainless steel, Anderson says. He adds that streamlined supply chains will reduce costs and improve delivery times and quality.

While they work to reduce costs, Anderson says manufacturers are finding ways to enhance equipment operability. “We are improving the centrifuge’s programming and interface, and adding onboard sensors so the operator can obtain a clear picture what is happening within the centrifuge,” he illustrates.

New centrifuges can include sensors for temperature monitoring, flow sensors, specific gravity sensors, amperage loading on the motors, temperature sensors on the bearings, level sensors within the centrifuge, and wear sensors on the scroll’s flight, Anderson details. These sensors will help the user automate the centrifuge’s operation and facilitate global performance monitoring through Web-based applications, he concludes.

Latshaw Drilling’s Trent Latshaw says improvements in rig designs, downhole motors, and fluids handling equipment are only a small part of a larger effort to improve drilling efficiency. “Polychrystalline diamond compact bits, measurement-while-drilling tools and rotary steerables will continue to be major drivers,” he predicts.

“The world has changed with respect to domestic exploration, drilling, and production,” he says. “Unconventional development has expanded the United States’ oil and gas reserves dramatically, but it also has increased the complexity of the technology needed to drill, log, and complete a well.

“Total well drilling, completion and construction costs range from $7 million to $8 million in many of the established shale plays, particularly for wells with ultralong laterals.” he says. “In the Granite Wash, drilling and completing a well can carry a price tag exceeding $8 million. Given these costs, it is imperative for operators and contractors to be aware of the latest technology.”

This paper documents the results of a new stage of development in the application of coiled-tubing drilling (CTD). Combining CTD technology with a conventional jointed-pipe workover capability re

8613371530291

8613371530291