pressure compensated hydraulic pump how it works supplier

Hydraulic pumps are an incredibly important component within hydraulic systems. IFP Automation offers a variety of pump and hydraulic system products that deliver exceptional functionality and durability. Our partner Parker’s extensive line of hydraulic pumps deliver ideal performance in even the most demanding industrial and mobile applications. In this post, we are going to spend time discussing pressure compensated and load sensing hydraulic pumps.

Do to the surface area of the servo piston and the pressure exerted on that area, a force is generated that pushes the swash plate of the pump to a lower degree of stroke angle.

The pump tries to maintain compensator setting pressure, and will provide whatever flow (up to it’s maximum flow rate) that is necessary to reach that pressure setting.

For more information on how you can make use of hydraulic pump technology in your applications, please contact us here to receive a personalized contact by an IFP Application Engineer:

IFP Automation supplies innovative technology and design solutions to the automation and mobile marketplaces. Our firm is a technology supplier specializing in the design and supply of automation and motion control products to OEM, integrator, and end user customers. Companies partner with IFP because they like the depth of our product and application knowledge and our commitment to outstanding customer service.

A pressure compensator is a device built into some pumps for the purpose of automatically reducing (or stopping) pump flow if system pressure sensed on the pump outlet port, should rise above a pre-set desired maximum pressure (sometimes called the "firing" pressure). The compensator prevents the pump from being overloaded if an overload is placed on the hydraulic system.

A compensator is built into the pump at the factory and usually cannot be added in the field. Any pump built with variable displacement can be controlled with a compensator. These include several types of axial piston pumps and unbalanced (single lobe) vane pumps. Radial piston pumps can sometimes be built with variable displacement but do not lend themselves readily to this action. Most other positive displacement pumps including internal and external gear, balanced (double lobe) vane, gerotor, and screw types cannot be built with variable displacement.

Figure 1 is a schematic of a check valve axial piston pump, variable displacement, controlled with a pressure compensator. The pistons, usually 5, 7, or 9 in number, are stroking inside a piston block which is keyed to and is rotating with the shaft. The left ends of the pistons are attached through swivel joints, to piston shoes which bear against and slide around on the swash plate as the piston block rotates. The swash plate itself does not rotate; it is mounted on a pair of trunnions so it can swivel from neutral (vertical) position to a maximum tilt angle. The angle which the swash plate makes to the vertical causes the pistons to stroke, the length of stroke being proportional to the angle. Normally, at low system pressures, the swash plate remains at its maximum angle, held there by spring force, hydraulic pressure, or by the dynamics of pump construction, and pump flow remains at maximum. The compensator acts by hydraulic pressure obtained internally from the pump outlet port. When pump pressure rises high enough to over-come the adjustable spring behind the compensator piston, the "firing" pressure has been reached, and the compensator piston starts to pull the swash plate back toward neutral, reducing pump displacement and output flow. The spring in the compensator can be adjusted for the desired maximum or "firing" pressure.

Under working conditions, on a moderate system overload, the compensator piston reduces the swash plate angle just enough to prevent the system pressure from exceeding the "firing" pressure adjusted on the compensator. On severe overloads the compensator may swing the swash plate back to neutral (vertical) to reduce pump flow to zero.

Maximum Displacement Stops. Some pumps are available with internal stops to limit the tilt angle of the swash plate. These stops limit the maximum flow and limit the HP consumption of the pump. They may be fixed stops, factory installed and inaccessible from the outside, or they may be externally adjustable with a wrench.

Manual Control Lever. Some pressure compensated pumps, especially hydrostatic transmission pumps, are provided with an external control lever to enable the operator to vary the swash plate angle (and flow) from zero to maximum. On these pumps the pressure compensator is arranged to override the manual lever and to automatically reduce the swash plate angle if a system overload should occur even though the operator control lever is still shifted to maximum displacement position.

Basically the pressure compensator is designed to unload the pump when system pressure reaches the maximum design pressure. When the pump is unloaded in this way, there is little HP consumed and little heat generated even though pressure remains at the maximum level, because there is no flow from the pump.

Variable displacement pumps are usually more expensive than fixed displacement types, but are especially useful in systems where several branch circuits are to be supplied from one pump, and where full pressure may be required simultaneously in more than one branch, and where the pump must be unloaded when none of the branches is ill operation. If individual 4-way valves are used in each branch, each valve must have a closed center spool. The inlet ports on all 4-way valves must be connected in parallel across the pump line. However, if all branch circuits are operated from a bank valve of the parallel type, a pressure compensated variable displacement pump may not be necessary; a fixed displacement pump, gear, vane, or piston, may serve equally well because the bank valve will unload the pump when all valve handles are placed in neutral, but when two or more handles are simultaneously shifted, their branch circuits will automatically be placed in a parallel connection.

As in all hydraulic systems, more pump oil will flow to the branch with the lightest load. Bank valve handles can be modulated to equalize the flow to each branch. When individual 4-way valves are used in each branch, flow control valves may be installed in the branch circuits and adjusted to give the flow desired in each branch.

Figure 2 shows a multiple branch circuit in which a variable displacement pump is used to advantage. Individual 4-way valves, solenoid operated, are used for each branch, and they have closed center porting. Please refer to Design Data Sheet 54 for possible drift problems on a pressure manifold system. A pressure relief valve is usually required even with a pressure compensated pump due to the time interval required for the swash plate to reduce its tilt angle when a sudden overload occurs. The relief valve will help absorb part of the pressure spike generated during this brief interval. It should be adjusted to crack at about 500 PSI higher than the pressure adjustment of the compensator piston spring to prevent oil discharge across it during normal operation.

All hydrostatic transmission systems use a variable displacement pump with pressure compensator, and often combine the compensator with other controls such as the horsepower input limiter, load sensing, flow sensing, or constant flow control.

© 1990 by Womack Machine Supply Co. This company assumes no liability for errors in data nor in safe and/or satisfactory operation of equipment designed from this information.

Pressure compensated pumps, pressure compensated flow controls or even just straight-up pressure compensators – these terms are thrown around constantly. But unless you’re a hydraulic specialist, you may not know what these are, let alone what they do. Of course, you’ve probably heard of systems analysts and cartographers too, but even thoseguys don’t know what they do.

The word pressureis self-explanatory, but just considering the meaning of compensategoes far to explain its use here. The dictionary says: reduce or counteract (something unwelcome or unpleasant) by exerting an opposite force or effect. Take that pressure!Your shenanigans are not welcome here! Okay, so we do want pressure and lots of it. But sometimes we don’t, and that’s where a compensator comes in.

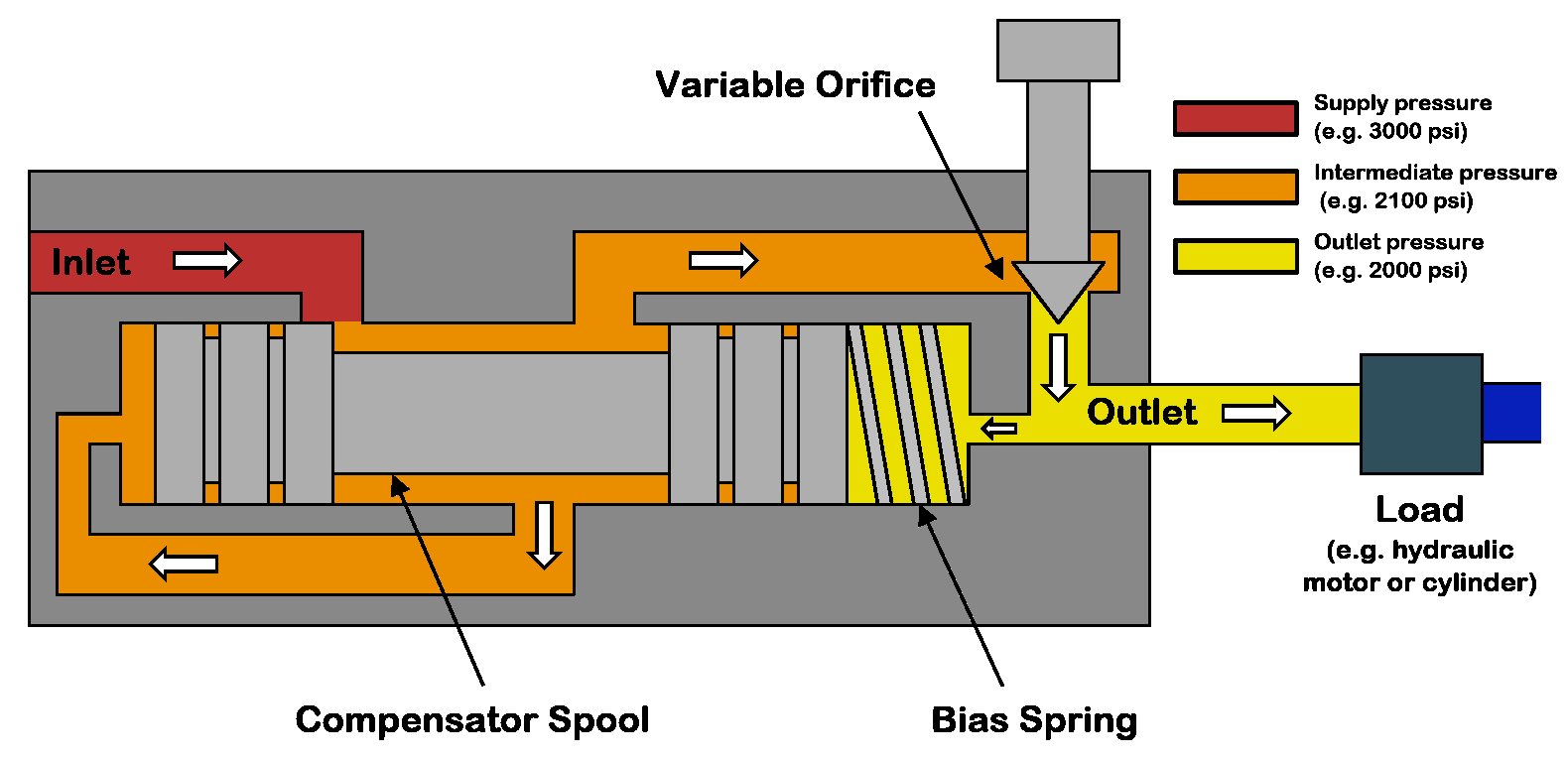

A pressure compensator works by comparing two pressure signals, one of which is a target and the other a pilot reading of downstream pressure. I’ve created a diagram showing a cutaway of a pressure compensated flow control and a symbol for the same (note, these valves are not identical). The primary difference between the two examples is the location of the compensator. The cutaway places the compensation before the variable orifice, while the symbol example places the compensator afterthe orifice. However, both will work so long as the compensator measures the pressure drop across the orifice.

Because flow rate is a function of pressure drop, and because pressure differential changes with flow rate, these understandings allow us to make sense of pressure compensator operation. Starting with the pressure compensated flow control symbol on the right, the flow path starts at port 1 and continues past port 3 out to the subcircuit being regulated.

The compensator has a spring value of 90 psi, and just like this example, most often, the spring value comes fixed. The compensator spool uses two pilot passages to measure pressure drop across the needle valve. In this case, port b measures pressure upstream of the needle valve at port 1, while port a measures downstream pressure at port 2.

The compensator spool will open or close itself to maintain 90 psi of differential pressure across the needle valve. Should load-induced pressure increase at port 2, the yellow pilot path to port a will push the spool backwards to open the combined flow path from port 1 to port 3. Should downstream pressure again decrease or supply pressure upstream of port 1 increase, any differential pressure than 90 psi will push the valve closed to restrict flow.

The cutaway example works much the same way. The red inlet flow must first pass a metering notch before entering the orange chamber, where the flow accesses its input. Next, metered flow crosses from orange to yellow before exiting the valve at the top. The yellowpassage comprises the differential pressure to the tune of the spring (assume 90 psi once again) trapped by the magenta spool. The difference in pressure between the orange and yellow defines the pressure drop through the needle valve.

Should downstream load-induced pressure at yellow start to decrease pressure drop from orange to yellow, the magenta spool moves backwards to open the flow path from red to orange, thereby increasing flow to sustain 90 psi pressure drop. Conversely, should pump-side pressure increase upstream of red, the increased pressure in the orange chamber will close the magenta spool against the spring. With less flow entering the orange chamber, pressure drop from orange to yellow remains stable at 90 psi.

In many ways, a pressure compensator is both a pressure and flow valve, but really quite simple in operation. For more information on pressure compensators, watch the Lunchbox Session videos on the subject. Expertly narrated by Carl Dyke, the first in the series can be found here.

www.powermotiontech.com is using a security service for protection against online attacks. An action has triggered the service and blocked your request.

Please try again in a few minutes. If the issue persist, please contact the site owner for further assistance. Reference ID IP Address Date and Time 8bf2006c85a66667641f5dd58dcb3d35 63.210.148.230 03/12/2023 08:49 AM UTC

Piston pumps are durable and relatively simple devices. A basic piston pump is made up of a piston, a chamber, and two valves. The pump operates by driving the piston down into the chamber, thereby compressing the media inside. In a hand pump, this is usually air. Once the pressure of the air exceeds that of the outlet valve spring, the compressed media goes through the open outlet valve. When the piston is drawn back up, it opens the inlet valve and closes the outlet valve, thereby utilizing suction to draw in new media for compression.

Although somewhat expensive, piston pumps are among the most efficient types of pumps. They have an excellent pressure rating (as high as 10,000 psi), but their design makes them susceptible to contaminants. They provide an excellent solution for many high-pressure hydraulic oil pumping applications.

Axial piston pumps are positive displacement pumps that use multiple cylinders grouped around a central axis. The group of cylinders, usually containing an odd number, is called a cylinder block. The pistons within each cylinder are attached to a swashplate. The swashplate is also known as a cam or wobble plate and attaches to a rotating shaft. As the shaft turns, the angle of the swashplate changes, which drives the pistons in and out of their respective cylinders.

Since the swashplate is at an angle to the axis of rotation, the pistons must reciprocate axially as they orbit around the cylinder block axis. The axial motion of the pistons is sinusoidal. As a piston rises, it moves toward the valve plate. At this point in the rotation, the fluid trapped between the buried end of the piston and the valve plate is expelled to the pump"s discharge port through one of the valve plate"s semi-circular ports. As the piston moves back toward the valve plate, the fluid is pushed through the discharge port of the valve plate.

Axial piston pumps can be designed as variable displacement piston pumps, making them very useful for controlling the speeds of hydraulic motors and cylinders. In this design, a swashplate is used to vary the depth to which each piston extends into its cylinder as the pump rotates, affecting the volume of discharge. A pressure compensator piston is used in some designs to maintain a constant discharge pressure under varying loads. Cheaper pressure washers sometimes use fixed-rate designs.

In a typical pressure-compensated pump, the swashplate angle adjusts through the action of a valve using pressure feedback to make sure that the pump output flow is precisely enough to maintain a designated pressure. If the load flow increases, the pressure momentarily decreases, but the pressure-compensation valve senses the decrease and then increases the swashplate angle to increase the pump’s output flow, restoring the desired pressure.

Axial piston pumps can contain most of the necessary circuit controls intrinsically by controlling the swash-plate angle, to regulate flow and pressure. They are very reliable and can allow the rest of the hydraulic system to which they’re attached to be very simple and inexpensive.

They are used to power the hydraulic systems of jet aircrafts, being gear-driven off of the turbine engine"s main shaft, and are often used for automotive air conditioning compressors for cabin cooling. The design of these pumps meets the limited weight and space requirement in the vehicle"s engine bay and reduces vibrations.

Pressure washers also use these pumps, and axial reciprocating motors are used to power many machines. They operate on the same principles as axial piston pumps, except that the circulating fluid is provided under substantial pressure and the piston housing rotates and provides shaft power to another machine. A typical use of an axial reciprocating motor is powering small earthmoving machines such as skid loader machines.

This guide provides a basic understanding of axial piston pumps. To find out more about other types of pumps, read our guide here. For more information on related products, consult our other product guides or visit the Thomas Supplier Discovery Platform to locate potential sources or view details on specific products.

On a recent project, there was a 25 horsepower motor running a torque limited piston pump. When we were doing performance testing, everything worked out fine. As soon as I left, the customer was complaining about excessive heat generation leading to downtime waiting for the oil to cool.

At first, I thought that a relief valve may be set below the compensator pressure, but a quick check showed they were operating correctly. So I did some research.

The problem wasn’t clear until I talked with the pump manufacturer. In order to keep a pressure compensated pump cool, the oil needs to be circulated internally. Depending on the manufacturer, 1/4 of the flow may be dumped back to tank to keep the pump cool.

Pressure compensated hydraulic systems tend to overheat because oil is continually circulated to keep the pump cool. The higher the standby pressure, the more heat created. Adding heat exchangers, shutting the pump down and lowering or having adjustable stand by pressure can reduce the heat generated.

So you have spent the extra money to get a piston pump, but do you know that there is a hidden danger in built in to these pumps? Let’s explore the danger

It turns out that pressure compensated systems are always moving oil, even when in standby. I found out that roughly 3 to 4 gpm were being dumped back to tank through the pump’s case drain at the compensator pressure. This was nearly 7 horsepower that was wasted.

This situation was not detected in testing, because we ran back to back tests with no idle time in between. Once the idle time was added in, we discovered that the oil temperature rose around 1-2 degrees per minute. An impressive feat on 100 gallons of hydraulic oil.

Adding a heat exchanger is a very obvious solution. These are usually forced air radiators made for hydraulics that are installed on the return line or the case drain line.

But as an engineer you should be asking yourself, “Why am I generating all this power just to heat the shop? That extra heat is going to make working in the summer excruciating.” All that an it is wasteful as well.

If we assume that we have 7 hp of wasted power from our pump during idle time, that is 5.2 kWh of energy. At 12 cents per kWh, that is $0.63 / hr of idle time.

If the only reason you are adding a heat exchanger is to reject idle time heat generation, there are many other options which we will explore below. Don’t let the simplicity of the a heat exchanger solution be where you stop. Keep reading.

As an engineer, the first step should always be fully diagnosing the root cause and not just masking the symptom. If you notice excessive idle time, make inquiries as to why the machine idles so much. Is an operator waiting on another process? Is it breaktime? They are many reasons for high idle time.

If the idle time can be modified by a process change or other external change, do that. However, don’t let that be your only change. People and processes aren’t perfect so expect those types of changes to occasionally fail.

This one is pretty self explanatory. If the system doesn’t need to be on, shut it down. If the system isn’t running, it can’t create heat. In fact, it has the opportunity to reject heat out of the system. Win-win!

Luckily, pressure compensated systems will start in a loaded condition. There should be no (or little) pressure on the outlet and compensator. This means that when starting the motor, it won’t be anywhere near fully loaded. Since there is no pressure, it will take 1-3 seconds for the pump to produce enough pressure to load up the compensator. This will usually be long enough to minimize startup loads on the motor.

If the machine is PLC controlled, adding a timer is easy to do when the machine is idle. This will be a good back up to the case where an operator accidentally leaves the system on when it is break time.

In the machine discussed above, we added a 2 minute timer for periods when there were no outputs given to any function. This was a great protection from heat generation, plus it was a signal to the operator that he or she was taking too long. Yes, it also had the side effect of increased production.

If excessive motor startup is a real concern, you may want to add a restart delay. This is common in HVAC systems where it is common to see a 5 minute ‘compressor delay’. This delay probably adds many hours of life to your HVAC system.

In some hydraulic systems, you just don’t need the system pressure you designed for. As a good designer, you have calculated your pressures and flows for less than what is available. As a result, you can reduce the standby pressure, but only minimally.

I say minimally, because there isn’t a drastic reduction in power with this one. However, you know your machine better than I do, so maybe there is more energy savings here.

This option is the most expensive and most efficient. By using an electro-proportional relief valve (DO3 P to T relief valve for industrial applications), you can set the compensator pressure for exactly what you need for the current function. As the functions change, the compensator pressure changes.

This is the most expensive option because your PLC system is going to have to output an analog signal (usually 0 – 10VDC) to control the electro-proportional relief valve (also expensive). As a good designer, you will also want a pressure sensor to provide feedback on the system.

However, this system is fully customizable and can act similiar to a load sensing mobile system. Through careful programming, you can tailor your pressure setting to what that function needs at any particular time.

Be cautious, the programming can get very complicated. It may not seem to be a big deal now, but will cause headaches in years to come when you or others will need to service the machine.

This is a much simpler version of the adjustable compensator option above. In this scenario, we would have one or more compensator relief valves switched on or off by non-proportional solenoid valves.

In this system, there would be one relief valve (main relief below) tied directly to the compensator and other relief valves are separated from the pressure line by 2 position, 2 way, normally closed solenoid operated valve. The main valve must be set at the maximum desired pressure so that if all else fails, the system will have a direct path of pressure control. The other valves can be activated, one at a time, to control the pressure for certain pressures.

This system cost is also reduced from the adjustable relief valve option because it eliminates the needed analog control system and extra programming for the PLC.

Additionally, the system can be made to look quite neat as well. Having a multisection DO3 manifold with the pressure port connected to the compensator will provide the foundation. Often, you can get the main relief valve already incorporated into the manifold which is a big bonus. You can then add solenoid valves on as the first row. On top of those valves you can add the individual relief valves.

If none of the sections are energized, the pump will create the maximum pressure which is set in the manifold relief valve. If one or more sections are activated, the pump will create pressure to the lowest set active pressure. In the schematic above, you can adjust the compensator pressure to 600 psi, 1200 psi, 2200 psi or 2750 psi depending on which sections are activated.

This can be a subset of several other options. If your system idles for long periods of time, you can just have a 2 position, 2 way, normally closed solenoid valve dump the pressure to tank. This will destroke the pump and not create any heat.

Another option on this is to couple it with a timer so that if there is no demand for the system hydraulics, the solenoid will activate and the pressure will be reduced. When demand for higher pressures is needed, the PLC will deactivate this solenoid.

I actually chose two of these solutions. First, I put a two minute timer on when the system is in normal standby. There is also a 25 minute timer when the system is in the cutting mode. At the 25 minute cycle, only 500 psi is needed to operate a hydraulic motor and control the travel of a saw.

In cutting mode, I also reduced the standby pressure from 2750 psi to 500 psi reducing the needed power by 82%. Sweet! I accomplished this by adding a second compensator relief valve that is activated by a 2 position 3 way valve.

Pressure compensated systems are generally more efficient and with a torque limiter they will give you the best performance of any other hydraulic system. Unfortunately, they do have the drawback of heat generation when in standby mode. If the solutions above are applied, you can often eliminate the need for a heat exchanger.

On a recent project, there was a 25 horsepower motor running a torque limited piston pump. When we were doing performance testing, everything worked out fine. As soon as I left, the customer was complaining about excessive heat generation leading to downtime waiting for the oil to cool.

At first, I thought that a relief valve may be set below the compensator pressure, but a quick check showed they were operating correctly. So I did some research.

The problem wasn’t clear until I talked with the pump manufacturer. In order to keep a pressure compensated pump cool, the oil needs to be circulated internally. Depending on the manufacturer, 1/4 of the flow may be dumped back to tank to keep the pump cool.

Pressure compensated hydraulic systems tend to overheat because oil is continually circulated to keep the pump cool. The higher the standby pressure, the more heat created. Adding heat exchangers, shutting the pump down and lowering or having adjustable stand by pressure can reduce the heat generated.

So you have spent the extra money to get a piston pump, but do you know that there is a hidden danger in built in to these pumps? Let’s explore the danger

It turns out that pressure compensated systems are always moving oil, even when in standby. I found out that roughly 3 to 4 gpm were being dumped back to tank through the pump’s case drain at the compensator pressure. This was nearly 7 horsepower that was wasted.

This situation was not detected in testing, because we ran back to back tests with no idle time in between. Once the idle time was added in, we discovered that the oil temperature rose around 1-2 degrees per minute. An impressive feat on 100 gallons of hydraulic oil.

Adding a heat exchanger is a very obvious solution. These are usually forced air radiators made for hydraulics that are installed on the return line or the case drain line.

But as an engineer you should be asking yourself, “Why am I generating all this power just to heat the shop? That extra heat is going to make working in the summer excruciating.” All that an it is wasteful as well.

If we assume that we have 7 hp of wasted power from our pump during idle time, that is 5.2 kWh of energy. At 12 cents per kWh, that is $0.63 / hr of idle time.

If the only reason you are adding a heat exchanger is to reject idle time heat generation, there are many other options which we will explore below. Don’t let the simplicity of the a heat exchanger solution be where you stop. Keep reading.

As an engineer, the first step should always be fully diagnosing the root cause and not just masking the symptom. If you notice excessive idle time, make inquiries as to why the machine idles so much. Is an operator waiting on another process? Is it breaktime? They are many reasons for high idle time.

If the idle time can be modified by a process change or other external change, do that. However, don’t let that be your only change. People and processes aren’t perfect so expect those types of changes to occasionally fail.

This one is pretty self explanatory. If the system doesn’t need to be on, shut it down. If the system isn’t running, it can’t create heat. In fact, it has the opportunity to reject heat out of the system. Win-win!

Luckily, pressure compensated systems will start in a loaded condition. There should be no (or little) pressure on the outlet and compensator. This means that when starting the motor, it won’t be anywhere near fully loaded. Since there is no pressure, it will take 1-3 seconds for the pump to produce enough pressure to load up the compensator. This will usually be long enough to minimize startup loads on the motor.

If the machine is PLC controlled, adding a timer is easy to do when the machine is idle. This will be a good back up to the case where an operator accidentally leaves the system on when it is break time.

In the machine discussed above, we added a 2 minute timer for periods when there were no outputs given to any function. This was a great protection from heat generation, plus it was a signal to the operator that he or she was taking too long. Yes, it also had the side effect of increased production.

If excessive motor startup is a real concern, you may want to add a restart delay. This is common in HVAC systems where it is common to see a 5 minute ‘compressor delay’. This delay probably adds many hours of life to your HVAC system.

In some hydraulic systems, you just don’t need the system pressure you designed for. As a good designer, you have calculated your pressures and flows for less than what is available. As a result, you can reduce the standby pressure, but only minimally.

I say minimally, because there isn’t a drastic reduction in power with this one. However, you know your machine better than I do, so maybe there is more energy savings here.

This option is the most expensive and most efficient. By using an electro-proportional relief valve (DO3 P to T relief valve for industrial applications), you can set the compensator pressure for exactly what you need for the current function. As the functions change, the compensator pressure changes.

This is the most expensive option because your PLC system is going to have to output an analog signal (usually 0 – 10VDC) to control the electro-proportional relief valve (also expensive). As a good designer, you will also want a pressure sensor to provide feedback on the system.

However, this system is fully customizable and can act similiar to a load sensing mobile system. Through careful programming, you can tailor your pressure setting to what that function needs at any particular time.

Be cautious, the programming can get very complicated. It may not seem to be a big deal now, but will cause headaches in years to come when you or others will need to service the machine.

This is a much simpler version of the adjustable compensator option above. In this scenario, we would have one or more compensator relief valves switched on or off by non-proportional solenoid valves.

In this system, there would be one relief valve (main relief below) tied directly to the compensator and other relief valves are separated from the pressure line by 2 position, 2 way, normally closed solenoid operated valve. The main valve must be set at the maximum desired pressure so that if all else fails, the system will have a direct path of pressure control. The other valves can be activated, one at a time, to control the pressure for certain pressures.

This system cost is also reduced from the adjustable relief valve option because it eliminates the needed analog control system and extra programming for the PLC.

Additionally, the system can be made to look quite neat as well. Having a multisection DO3 manifold with the pressure port connected to the compensator will provide the foundation. Often, you can get the main relief valve already incorporated into the manifold which is a big bonus. You can then add solenoid valves on as the first row. On top of those valves you can add the individual relief valves.

If none of the sections are energized, the pump will create the maximum pressure which is set in the manifold relief valve. If one or more sections are activated, the pump will create pressure to the lowest set active pressure. In the schematic above, you can adjust the compensator pressure to 600 psi, 1200 psi, 2200 psi or 2750 psi depending on which sections are activated.

This can be a subset of several other options. If your system idles for long periods of time, you can just have a 2 position, 2 way, normally closed solenoid valve dump the pressure to tank. This will destroke the pump and not create any heat.

Another option on this is to couple it with a timer so that if there is no demand for the system hydraulics, the solenoid will activate and the pressure will be reduced. When demand for higher pressures is needed, the PLC will deactivate this solenoid.

I actually chose two of these solutions. First, I put a two minute timer on when the system is in normal standby. There is also a 25 minute timer when the system is in the cutting mode. At the 25 minute cycle, only 500 psi is needed to operate a hydraulic motor and control the travel of a saw.

In cutting mode, I also reduced the standby pressure from 2750 psi to 500 psi reducing the needed power by 82%. Sweet! I accomplished this by adding a second compensator relief valve that is activated by a 2 position 3 way valve.

Pressure compensated systems are generally more efficient and with a torque limiter they will give you the best performance of any other hydraulic system. Unfortunately, they do have the drawback of heat generation when in standby mode. If the solutions above are applied, you can often eliminate the need for a heat exchanger.

Another option is to utilize a load sense compensator. With a load sense compensator, this compensator will include a lighter spring setting to control the swash plate. Upstream pressure is ported into a load sense port on the pump, as the pressure requirement increases, the pressure acts against the load sense piston. Once the pressure requirement is higher than the offset, the pump swash plate angle changes and the pump begins to increase flow, by increasing the swash plate angle, until we have enough pressure to balance the piston. Once balanced, the flow remains steady until the load changes.

The offset pressure is normally 200-300 PSI. With a load sense compensator, the pump produces what the load requires plus the spring offset, normally 200-300 PSI.

This system will also utilize a standard compensator so if the system pressure increases enough, the pressure compensator will take control and reduce the swash plate angle to reduce the pressure.

Let’s look at my initial application but this time, it has a varying load. They conveyor requires 1500 PSI to move 50% of the time, but the balance of the time the system requires between 2250-2500 PSI to move the load.

With a standard pressure compensator, you would have to set the pump at 2600 PSI to accomplish the work. When the work only requires 1500 PSI, the pump will be trying to produce 2600 PSI. Fifty percent of the time, your system will be operating at 1100 PSI of inefficiency, which means heat. With a load sense compensator, when the load requires 1500 PSI, the pump will actually produce about 17-1800 PSI. Yes, this is 300 PSI inefficient, but that is much better than 1100 PSI inefficient.

With a varying load, the load sense is a much better system. For additional control, you can utilize an electronic proportional flow control or throttle. You can use an electrical signal to vary the hydraulic signal which is received by the pump’s load sense line. This would give you full electronic control of the amount of flow the pump produces.

There are additional control options which allow you to remotely control the pressure compensator. With this remote compensator control, you can set 2 or more different system pressures. With the ability of a variable piston pump to build 5,000 or more PSI; the additional setting can be used when operating components with a much lower pressure requirement.

The next control is a torque limiting or HP limiting control. By adding an additional spring and piston, you can set a pump to always maximize its allowable input torque, therefore, maximizing output flow and pressure at a defined setting.

In this application, you are operating large bore, long strong cylinder. The cylinder has a 10” bore and 150” stroke. During most of the stroke, the cylinder is not doing very much work and can operate at 800-1200 PSI. During the last 20” of stroke, we want to hit our system pressure of 4500 PSI, but we can move much slower.

Our pump has an output of 15 CIR, a maximum flow of about 113 gallons at 1750 RPM. Our prime mover is an electric motor, 75HP with a 1.15 service factor. I want to keep my cylinder moving as fast as possible, but I also want to ensure that I never exceed a power demand 82 HP.

At 82 HP, the pump can produce 1254 PSI at full output, 113 GPM. As the load requires more pressure, the pump will begin to reduce flow and increase pressure. At 90 GPM flow, the system will produce about 1560 PSI; at 60 GPM we can get almost 2350 PSI. At 4500 PSI, the pump flow will be reduced to about 31 GPM. The advantage of this pump is that the internal controls of the pump are adjusting to maximize flow and pressure at all times without exceeding the available HP.

If I wanted to use a pump which could produce 113 gallons of flow at 4500 PSI, I would need 296 HP. If I choose a 75 HP motor with a pressure compensated variable piston pump, the motor would stall before the pressure compensator could kick in and reduce the pump flow. Depending on the load, a load sense pump could also stall the 75 HP motor if the load pressure is high enough to use up the HP before the pressure compensator kicks in. With a torque limiting (HP) control, we utilize the full limits of the prime mover and maximize power usage.

Why would we want to add this extra complication to our hydraulic systems?Having a hydraulic pump which reduces its output to near zero when the system pressure reaches maximum saves the system from pointlessly forcing oil over a relief valve.

Whenever a system is at maximum pressure, and the pump is a fixed displacement model, like a gear pump, then the system is at maximum displacement as well.

The combination of these two maximums also means that the power requirement from the prime mover (diesel engine or electric motor) is at maximum as well.A prime mover at maximum power is consuming maximum energy (fuel or electricity). Much of this energy is being used for nothing other than a conversion to heat.

You could compare this to operating a truck at maximum throttle while it is parked against a solid wall of rock. You"ll burn a lot of fuel but you won"t be doing any useful work!

max flow: 7.8 GPMHyvair’s line of pressure compensated industrial piston pumps (PCP) are stocked with displacements from 0.49 cu.in/r. (8.0cc) to 4.27 cu.in/r. (70.0cc) and continuous pressure up to 3,000 PSI. All sizes in our industrial line are available with multiple control options from load sensing to dual pressure solenoid. Through drives are available on all pump sizes except the PCP33. The semi-cylindrical swash plate design allows for smooth, stable operation, increases efficiency and reduced noise by sealing pressure on its face. catalog pdf Cad File

Hyvair Corp. distinguishes itself from other component and system companies with total customer service. From design support in the earliest phases of your project, to just-in-time deliveries to meet your customer"s production schedule, Hyvair works with you as a team member - not just a supplier.

There are typically three types of hydraulic pump constructions found in mobile hydraulic applications. These include gear, piston, and vane; however, there are also clutch pumps, dump pumps, and pumps for refuse vehicles such as dry valve pumps and Muncie Power Products’ Live PakTM.

The hydraulic pump is the component of the hydraulic system that takes mechanical energy and converts it into fluid energy in the form of oil flow. This mechanical energy is taken from what is called the prime mover (a turning force) such as the power take-off or directly from the truck engine.

With each hydraulic pump, the pump will be of either a uni-rotational or bi-rotational design. As its name implies, a uni-rotational pump is designed to operate in one direction of shaft rotation. On the other hand, a bi-rotational pump has the ability to operate in either direction.

For truck-mounted hydraulic systems, the most common design in use is the gear pump. This design is characterized as having fewer moving parts, being easy to service, more tolerant of contamination than other designs and relatively inexpensive. Gear pumps are fixed displacement, also called positive displacement, pumps. This means the same volume of flow is produced with each rotation of the pump’s shaft. Gear pumps are rated in terms of the pump’s maximum pressure rating, cubic inch displacement and maximum input speed limitation.

Generally, gear pumps are used in open center hydraulic systems. Gear pumps trap oil in the areas between the teeth of the pump’s two gears and the body of the pump, transport it around the circumference of the gear cavity and then force it through the outlet port as the gears mesh. Behind the brass alloy thrust plates, or wear plates, a small amount of pressurized oil pushes the plates tightly against the gear ends to improve pump efficiency.

A cylinder block containing pistons that move in and out is housed within a piston pump. It’s the movement of these pistons that draw oil from the supply port and then force it through the outlet. The angle of the swash plate, which the slipper end of the piston rides against, determines the length of the piston’s stroke. While the swash plate remains stationary, the cylinder block, encompassing the pistons, rotates with the pump’s input shaft. The pump displacement is then determined by the total volume of the pump’s cylinders. Fixed and variable displacement designs are both available.

With a fixed displacement piston pump, the swash plate is nonadjustable. Its proportional output flow to input shaft speed is like that of a gear pump and like a gear pump, the fixed displacement piston pump is used within open center hydraulic systems.

As previously mentioned, piston pumps are also used within applications like snow and ice control where it may be desirable to vary system flow without varying engine speed. This is where the variable displacement piston pump comes into play – when the hydraulic flow requirements will vary based on operating conditions. Unlike the fixed displacement design, the swash plate is not fixed and its angle can be adjusted by a pressure signal from the directional valve via a compensator.

Flow and Pressure Compensated Combined – These systems with flow and pressure compensation combined are often called a load-sensing system, which is common for snow and ice control vehicles.

Vane pumps were, at one time, commonly used on utility vehicles such as aerial buckets and ladders. Today, the vane pump is not commonly found on these mobile (truck-mounted) hydraulic systems as gear pumps are more widely accepted and available.

Within a vane pump, as the input shaft rotates it causes oil to be picked up between the vanes of the pump which is then transported to the pump’s outlet side. This is similar to how gear pumps work, but there is one set of vanes – versus a pair of gears – on a rotating cartridge in the pump housing. As the area between the vanes decreases on the outlet side and increases on the inlet side of the pump, oil is drawn in through the supply port and expelled through the outlet as the vane cartridge rotates due to the change in area.

Input shaft rotates, causing oil to be picked up between the vanes of the pump which is then transported to pump outlet side as area between vanes decreases on outlet side and increases on inlet side to draw oil through supply port and expel though outlet as vane cartridge rotates

A clutch pump is a small displacement gear pump equipped with a belt-driven, electromagnetic clutch, much like that found on a car’s air conditioner compressor. It is engaged when the operator turns on a switch inside the truck cab. Clutch pumps are frequently used where a transmission power take-off aperture is not provided or is not easily accessible. Common applications include aerial bucket trucks, wreckers and hay spikes. As a general rule clutch pumps cannot be used where pump output flows are in excess of 15 GPM as the engine drive belt is subject to slipping under higher loads.

What separates this pump from the traditional gear pump is its built-in pressure relief assembly and an integral three-position, three-way directional control valve. The dump pump is unsuited for continuous-duty applications because of its narrow, internal paths and the subsequent likelihood of excessive heat generation.

Dump pumps are often direct mounted to the power take-off; however, it is vital that the direct-coupled pumps be rigidly supported with an installer-supplied bracket to the transmission case with the pump’s weight at 70 lbs. With a dump pump, either a two- or three-line installation must be selected (two-line and three-line refer to the number of hoses used to plumb the pump); however, a dump pump can easily be converted from a two- to three-line installation. This is accomplished by inserting an inexpensive sleeve into the pump’s inlet port and uncapping the return port.

Many dump bodies can function adequately with a two-line installation if not left operating too long in neutral. When left operating in neutral for too long however, the most common dump pump failure occurs due to high temperatures. To prevent this failure, a three-line installation can be selected – which also provides additional benefits.

Pumps for refuse equipment include both dry valve and Live Pak pumps. Both conserve fuel while in the OFF mode, but have the ability to provide full flow when work is required. While both have designs based on that of standard gear pumps, the dry valve and Like Pak pumps incorporate additional, special valving.

Primarily used on refuse equipment, dry valve pumps are large displacement, front crankshaft-driven pumps. The dry valve pump encompasses a plunger-type valve in the pump inlet port. This special plunger-type valve restricts flow in the OFF mode and allows full flow in the ON mode. As a result, the horsepower draw is lowered, which saves fuel when the hydraulic system is not in use.

In the closed position, the dry valve allows just enough oil to pass through to maintain lubrication of the pump. This oil is then returned to the reservoir through a bleed valve and small return line. A bleed valve that is fully functioning is critical to the life of this type of pump, as pump failure induced by cavitation will result if the bleed valve becomes clogged by contaminates. Muncie Power Products also offer a butterfly-style dry valve, which eliminates the bleed valve requirement and allows for improved system efficiency.

It’s important to note that with the dry valve, wear plates and shaft seals differ from standard gear pumps. Trying to fit a standard gear pump to a dry valve likely will result in premature pump failure.

Encompasses plunger-type valve in the pump inlet port restricting flow in OFF mode, but allows full flow in ON mode lowering horsepower draw to save fuel when not in use

Wear plates and shaft seals differ from standard gear pumps – trying to fit standard gear pump to dry valve likely will result in premature pump failure

Live Pak pumps are also primarily used on refuse equipment and are engine crankshaft driven; however, the inlet on a Live Pak pump is not outfitted with a shut-off valve. With a Live Pak pump, the outlet incorporates a flow limiting valve. This is called a Live Pak valve. The valve acts as an unloading valve in OFF mode and a flow limiting valve in the ON mode. As a result, the hydraulic system speed is limited to keep within safe operating parameters.

Outlet incorporates flow limiting valve called Live Pak valve – acts as an unloading valve in OFF mode and flow limiting valve in ON mode restricting hydraulic system speed to keep within safe operating parameters

A pressure-compensated flow control valve is designed to provide a constant volume flow rate regardless of the pressure drop across it. By contrast, non-pressure-compensated flow control valves have a variable flow rate that changes when the pressure drop fluctuates.

Pressure-compensated flow control valves are used in a variety of hydraulic applications. They are useful, for example, when it is necessary to maintain a constant speed on a hydraulic cylinder, regardless of the amount of load that the cylinder is under. Because speed is directly proportional to hydraulic fluid flow rate, a hydraulic cylinder’s speed depends on how much fluid is flowing through it.

In a flow control valve without pressure compensation, the flow rate will fluctuate depending on the load on the cylinder. A heavy load on the cylinder will increase the pressure at the valve’s outlet compared to one with a lighter load. By changing the pressure drop across the valve, the flow rate it delivers to the cylinder is altered. Pressure-compensated flow control valves adapt to such pressure changes to maintain a constant flow rate that provides fluid motion at constant speed

Pressure-compensated flow control valves are also useful in maintaining constant rpm of a hydraulic motor independent of load on the motor. Much like the example above, changing loads on the motor will result in a fluctuating pressure drop across the valve ahead of the motor. These fluctuations are compensated for by pressure-compensated flow control valves, which maintain the hydraulic motor’s rpm at a constant level.

It is possible for pressure-compensated flow control valves to compensate pressure fluctuations on either the supply (inlet) or the load (outlet) side of the valve.

Flow control valves that are pressure-compensated normally consist of a variable orifice and a pressure compensator incorporated into one valve body. Flow goes from the supply valve through the inlet and compensated orifice, around the compensated spool, through the variable orifice, and then out the outlet.

By adjusting the pass-through area of the orifice, the desired flow rate is set on the variable orifice. You can make this adjustment either manually using a knob, screw or lever on the valve. Alternatively, by means of electronic signals that are sent to an actuator attached to the variable orifice. Using the pressure compensator, a constant pressure drop is achieved across the variable orifice by modulating the flow of fluid entering the valve. It also provides a constant flow rate across the valve by adjusting the orifice between the inlet flow and the compensator spool.

Variable orifices are made up of valve stems that have a pointed end that can move toward and away from a seat in order to achieve different sizes of openings. Whenever the tip of the stem is in full contact with the seat, the orifice becomes closed, and no fluid can pass. With the stem tip moved away from the seat, the orifice opening becomes larger and more fluid can pass through.

A spool valve with a spring anchors the pressure compensator. Compensation spools consist of a cylindrical barrel with a plunger that slides inside. Plungers have thin and wide sections along their length. As long as the lands and ports are adjacent to each other, they block fluid flow. The wide sections of the barrel are called lands. Spools with narrow, waisted sections allow fluid to pass through them.

By applying a force to the end of the spool attached to the valve housing, a spring keeps the spool attached to it. An additional force is applied to the anchored end of the spool by flowing past the variable orifice in the outlet of the valve. There is a pressure gradient along the line leading from the pressure-compensated flow control valve to the load, such as a hydraulic motor or cylinder.

The fluid that has passed the variable orifice but not yet reached the inlet and compensator is ported to the other end of the spool (the end opposite the end attached to the spring). A force is applied to the spool at this end by the fluid that opposes the force applied by the load pressure and spring pressure. The opposing forces distort the opening of the orifice through which fluid flows from the flow source, modulating the opening of the orifice until the forces at either end of the spool are balanced.

Consequently, fluid flows from the supply, across the compensator spool, and through the variable orifice, while a constant pressure drop across the variable orifice keeps the flow rate constant regardless of changes in pressure between supply and load.

As fluid temperature increases, viscosity increases as well, affecting flow rate. A temperature-sensitive element is incorporated in some pressure-compensated flow control valves, which adapts the position of the compensator when fluid temperatures and viscosity vary. This ensures a constant flow rate regardless of fluid temperature and viscosity. By using a sharp-edged orifice design for the variable orifice, some designs are also able to minimize the variations in flow rate due to changes in viscosity.

An integral part of a pressure-compensated flow control valve is the pressure compensator. A valve without it would have a variable flow rate when pressure across the valve varies. If more fluid is forced through the valve as a result of a higher pressure drop, the flow rate will be higher; if the pressure drop is lower, the flow rate will be lower.

By automatically adjusting the volume flow rate from the flow supply to the variable orifice, the pressure compensator keeps the internal pressure drop across the variable orifice constant, regardless of the change in pressure drop between the inlet and outlet. With a constant internal pressure drop across the variable orifice, the valve always produces a constant volumetric flow rate regardless of the pressure differences between the valve inlet and outlet. T

his decreases the incoming input process on the inlet port to the lowest operation working pressure for the valve to output accurate flow rates. After regulation, this lowered pressure is applied to the proportional valve orifice, thereby allowing for consistent flow rates even with fluctuating input pressures. So long as the incoming pressure does not drop below the minimum required pressure, accurate proportional flow is maintained to the system.

Kelly Pneumatics offers its Pressure Compensated Proportional Valve for projects that require a pressure-compensated flow control valve. There is a mechanical pressure regulator built into the unit, which lowers the incoming input process on the inlet port to the lowest operating working pressure recommended for the valve to output accurate flow rates. By lowering the pressure after regulation, a consistent flow rate can be achieved despite fluctuating input pressures. A proportional flow to the system is maintained so long as the incoming pressure does not drop below the minimum required pressure.

These pumps are designed for applications where light weight design, lower displacements, and multiple configuration capabolities are design requirements.

This Pressure Compensated Piston Pump is one of many pumps that the Hydraulic Megastore has to offer and they are all available for next day delivery.

By maintaining the pressure and flow when demanded, internal leakage is reduced, generating less unwanted heat. Also, less strain is put on hoses and seals, providing a more reliable system. The use of flat-face O-ring face seal fittings and snap-to-connect fittings provide leak-free connections.

The integration of pumps, filter housing, and priority valve results in fewer and shorter lines, providing added reliability for greater productivity and less pressure loss and less flow restrictions.

The integrated pump assembly is attached to the right side of the pump drive housing. The charge pump section is a constant-flow gear-type pump. It draws oil through a suction screen from the rear differential case, providing low-pressure oil to the dual filtering system and to the integrated axial piston pump. Filtered oil not required by the integrated axial piston pump is routed to the clean oil reservoir for transmission and ground-drive pump usage.

Integrated axial piston pump is available in two sizes, 63 cc and 85 cc displacement. They are pressure-flow compensated axial piston pumps and provide oil to steering, brakes, hitch, SCVs, as well as ILSTM, ActiveSeatTM, and for power-beyond functions if equipped.

All functions return oil to the integrated dual filtering system, making oil available to the integrated axial piston pump. Oil not required by the integrated axial piston pump is supplied to the clean-oil reservoir.

Clean-oil reservoir is located in the top portion of the pump drive housing and holds 9.5 gallons of filtered oil. It receives excess oil that the integrated axial piston pump does not need. It serves as a reservoir for filtered oil to be used by the transmission pumps. When needed, it also supplies filtered oil to the ground-drive pump and the integrated axial piston pump. Also, with the use of large single-acting cylinders, the integrated axial piston pump may draw oil from the clean-oil reservoir as needed. Reservoir overflow oil provides lubrication for spiral gear set in differential.

Hydraulic system protection is provided by an oil level switch located in the clean-oil reservoir. If oil level is low, secondary functions (SCV, hitch, power beyond) will be reduced, maintaining oil for steering and brakes. At the same time, an indicator light and code will be generated, notifying the operator of a low-oil situation. This is to assure oil will be available for steering and brakes. Once oil level is satisfactory, secondary function will be restored and the indicator will stop.

There is also a temperature sensor located in the clean-oil reservoir. It is there to protect the transmission. The engine rpm will be reduced to 1500 rpm and only certain transmission speed will be obtained with cold oil. Once oil temperature is acceptable, complete engine and transmission functions will be resumed.

Priority valve is also integrated with the hydraulic pumps and the filter housing, resulting in fewer and shorter lines providing added reliability. It ensures that oil supply is available for steering and brakes. Excess oil is then available for other hydraulic system functions such as SCVs, hitch, power beyond, ILS, and Active Seat.

Filters: Two 10 micron filters working in parallel filtering hydraulic and transmission oil results in 17% more flow capacity and extends filter service interval to 1500 hours.

IVT and PST transmission pumps are constant-flow gear-type pumps located on the left side of the pump drive housing. The inside pump section of the tandem pump on IVT"s supplies the transmission hydro unit. The outside pump section on IVT"s and the single pump on the PST"s perform the same functions. Not only do they provide oil for transmission functions, but they also supply hitch and SCV pilot stage oil and PTO and differential lock control oil.

8613371530291

8613371530291