what causes hydraulic pump cavitation manufacturer

The second leading cause of hydraulic pump failure, behind contamination, is cavitation. Cavitation is a condition that can also potentially damage or compromise your hydraulic system. For this reason, understanding cavitation, its symptoms, and methods of prevention are critical to the efficiency and overall health of not just your hydraulic pump, but your hydraulic system as a whole.

The product of excessive vacuum conditions created at the hydraulic pump’s inlet (supply side), cavitation is the formation, and collapse of vapors within a hydraulic pump. High vacuum creates vapor bubbles within the oil, which are carried to the discharge (pressure) side. These bubbles then collapse, thus cavitation.

This type of hydraulic pump failure is caused by poor plumbing, flow restrictions, or high oil viscosity; however, the leading cause of cavitation is poor plumbing. Poor plumbing is the result of incorrectly sized hose or fittings and or an indirect (not straight or vertical) path from the pump to the reservoir. Flow restrictions, for example, include buildup in the strainer or the use of an incorrect length of hose or a valve that is not fully open. Lastly, high oil viscosity—or oil that is too viscous—will not flow easily to the pump. Oil viscosity must be appropriate for the climate and application in which the hydraulic pump is being used.

The greatest damage caused by cavitation results from the excessive heat generated as the vapor bubbles collapse under the pressure at the pump outlet or discharge side. On the discharge side, these vapor bubbles collapse as the pressure causes the gases to return to a liquid state. The collapses of these bubbles result in violent implosions, drawing surrounding material, or debris, into the collapse. The temperature at the point of implosion can exceed 5,000° F. Keep in mind that in order for these implosions to happen, there must be high vacuum at the inlet and high pressure at the outlet.

Cavitation is usually recognized by sound. The pump will either produce a “whining” sound (more mild conditions) or a “rattling” sound (from intense implosions) that can sound like marbles in a can. If you’re hearing either of these sounds, you first need to determine the source. Just because you hear one of these two sounds doesn’t guarantee that your hydraulic pump is the culprit.

To isolate the pump from the power take-off (PTO) to confirm the source, remove the bolts that connect the two components and detach the pump from the PTO. Next, run the PTO with no pump and see if the sound is still present. If not, it is safe to assume your hydraulic pump is the problem.

Another sign you may be experiencing cavitation is physical evidence. As part of your general maintenance, you should be inspecting and replacing the hydraulic oil filter"s elements at regular intervals based on the duty cycle of the application and how often it is used. If at any time during the inspection and replacement of these elements you find metallic debris, it could be a sign that you’re experiencing cavitation in the pump.

The easiest way to determine the health of your complete hydraulic circuit is to check the filter. Every system should have a hydraulic oil filter somewhere in-line. Return line filters should be plumbed in the, you guessed it, return line from the actuator back to tank—as close to the tank as possible. As mentioned earlier, this filter will have elements that should be replaced at regular intervals. If you find metallic debris, your pump could be experiencing cavitation. You’ll then need to flush the entire system and remove the pump for inspection.

Conversely, if you’ve already determined the pump to be damaged, you should remove the filter element, cut it open, and inspect it. If you find a lot of metal, you’ll need to flush the entire system and keep an eye on the other components that may be compromised as a result.

Once cavitation has been detected within the hydraulic pump, you’ll need to determine the exact cause of cavitation. If you don’t, cavitation can result in pump failure and compromise additional components—potentially costing you your system.

Since the pump is fed via gravity and atmospheric pressure, the path between the reservoir and the pump should be as vertical and straight as possible. This means that the pump should be located as close to the reservoir as is practical with no 90-degree fittings or unnecessary bends in the supply hose. Whenever possible, be sure to locate the reservoir above the pump and have the largest supply ports in the reservoir as well. And don"t forget, ensure the reservoir has a proper breather cap or is pressurized (3–5 PSI), either with an air system or pressure breather cap.

Be sure the supply line shut-off valve (if equipped) is fully open with no restrictions. This should be a “full-flow” ball valve with the same inside diameter (i.d.) as the supply hose. If feasible, locate a vacuum gauge that can be T’d into the supply line and plumb it at the pump inlet port. Activate the PTO and operate a hydraulic function while monitoring the gauge. If it reads >5 in. Hg, shut it off, and resume your inspection.

A hose with an inner bladder vulcanized to a heavy spiral is designed to withstand vacuum conditions as opposed to outward pressure. The layline will also denote the size of the hose (i.d.). You can use Muncie Power’s PPC-1 hydraulic hose calculator to determine the optimal diameter for your particular application based on operating flows.

Another consideration, in regards to the inlet plumbing, is laminar flow. To reduce noise and turbulence at the pump inlet, the length of the supply hose should be at least 10 times its diameter. This means that any type of shut-off valve or strainer at the reservoir should be at least 10 diameters from the pump inlet. A flared, flange-style fitting at the pump inlet can also reduce pump noise by at least 50 percent compared to a SAE, JIC, or NPT fitting.

Selecting the proper viscosity of hydraulic fluid for your climate and application is also critical. Oil that is too viscous will not flow as easily to the pump. Consult your local hydraulic oil supplier for help selecting the optimal fluid viscosity.

By maintaining a regular maintenance schedule, remaining vigilant for any signs or symptoms, and taking preventative measures, the good news is that you should be able to prevent cavitation and experience efficient operation for the duration of your pump’s lifespan.

Poor plumbing is the leading cause of cavitation and can be prevented by selecting a properly sized hose, choosing the appropriate fittings, ensuring the most direct, straight routing from the pump to the reservoir, etc.

Two leading causes why hydraulic pumps usually fail are: (1) contamination and (2) cavitation. In order to prevent any potential damage to your entire hydraulic system, it’s imperative to understand cavitation, the indications or symptoms from your system it is occurring, as well as the preventive measures.

How does cavitation happen exactly? It starts when vapor bubbles in the oil are created due to high vacuum. When these vapor bubbles are carried and collapsed on the pump outlet (discharge side), cavitation happens.

Make Sure Oil flow Paths are Straight – Hydraulic pumps are being supplied via atmospheric pressure and gravity, so it’s ideal to place the reservoir above it. Make sure that the path is as straight and vertical as possible. Keep an eye on bent or twisted supply hose.

Check Laminar Flow – If you’re hearing turbulence or noise in pump inlet, make sure that the supply hose length is the correct ratio to its diameter. A flange-style, flared fitting in the pump inlet can also help in eliminating pump noise.

Check Proper Viscosity – It"s important to choose the hydraulic fluid with appropriate viscosity for your application and climate. Consult with your supplier for professional help in choosing the optimal fluid viscosity.

With regular maintenance, keeping an eye on symptoms, and taking preventive measures, you’d be able to avoid cavitation and expect efficient operation from your hydraulic pumps.

Cavitation is the second leading hydraulic pump failure cause, behind contamination. As this can potentially cause damage and compromise your hydraulic system, it is important to understand what it is as well as its symptoms.

Cavitation is the product of excessive vacuum conditions created at the hydraulic pump’s inlet. This causes high vacuums to create vapour bubbles within the hydraulic oil, these are then carried to the discharge side before they then collapse - causing cavitation to occur.

These high vacuums and cavitation are often caused by poor plumbing, flow restrictions, or high oil viscosity. Poor plumbing is often the main cause of this and is due to an incorrectly sized hose or fittings and/or an indirect (not straight or vertical) path from the pump to the reservoir.

The easiest way to identify cavitation is through noise. The hydraulic pump will either emit a “whining” or a “rattling” sound. If you hear either or both of these sounds you will need to isolate the pump to make sure that this is where it is coming from.

As part of your general maintenance, you should be inspecting and replacing the hydraulic oil filter"s elements at regular intervals based on the duty cycle of the application and how often it is used. If when replacing the filter you come to find metallic debris this could be a sign that cavitation is occurring within the pump. In this case it is best to flush the entire system and detach the pump for closer inspection.

When replacing the filter you find that it is damaged, this could be due to cavitation. To find out if this is the case, remove the filter element of the hydraulic system and inspect for metallic debris. If there is some present then flush the system to prevent damage being caused elsewhere. Now that you have identified cavitation has been occurring within the hydraulic pump, you’ll need to determine the exact cause of cavitation.

As there are so many causes and damage results from cavitation, it is important to regularly check your hydraulic pump for signs of cavitation. By simply checking the pump and filter you can prevent your hydraulic system from failing when you most need it.

Hydraulic pumps come in a variety of sizes, styles and fuel types, so if you are having issues with your pump browse our great range for a replacement or get in contact with our expert team for advice on any hydraulic issue.

Cavitation is the term used to describe the formation of gas cavities within a liquid. In a hydraulic system, this is normally taken to mean formation of vapor bubbles within the oil. But it can also mean dissolved air coming out of solution in the oil.

In a hydraulic system, the formation of gas cavities is usually, but not always, associated with the presence of a vacuum (negative gauge pressure). And the presence of vacuum-induced, mechanical forces can be far more damaging to hydraulic components than pressure-induced bubble implosion.

Whatever the cause, cavitation is detrimental to the long-run reliability of any hydraulic system. Which means tolerating its occurrence is a costly mistake.

Hydraulic pumps are used in various industries to pump liquid, fluid, and gas. Although this equipment features robust construction, it may fail at times due to various issues. Cavitation is one of the serious issues faced by this equipment. Like all other technical issues, right planning as well as troubleshooting will help avoid this issue to a large extent. What is pump cavitation and how to troubleshoot these it?

It is seen that many times, Strong cavitation that occurs at the impeller inlet may lead to pump failure. Pump cavitation usually affects centrifugal pumps, which may experience several working troubles. At times, submersible pumps may also be affected by pump cavitation.

Non-inertial Cavitation: This type of cavitation is initiated when a bubble in a fluid undergoes shape alterations due to an acoustic field or some other type of energy input.

Suction Cavitation: This cavitation is brought by high vacuum or low-pressure conditions that may affect the flow. These conditions will reduce the flow, and bubbles will be formed near the impeller eye. As these bubbles move towards the pump’s discharge end, they are compressed into liquid, and they will implode against the edge of the impeller.

Discharge Cavitation: Here, cavitation occurs when the pump’s discharge pressure becomes abnormally high, which in turn affects its efficiency. High discharge pressure will alter the flow of fluid, which leads to its recirculation inside the pump. The liquid will get stuck in a pattern between the housing, as well as the impeller, thereby creating a vacuum. This vacuum creates air bubbles, which will collapse and damage the impeller.

Sound: The pump affected by cavitation will produce a marble, rock, or gravel type of sound when in motion. The sound will begin as a small disturbance and its intensity will increase as the material slowly chips away from the surface of the pump.

Metallic Debris: If during the maintenance, you find metallic debris on the filter of the hydraulic pump then it may be a symptom of cavitation. One of the easiest ways to confirm it is to check the filter. If any debris is found, you should clean the entire system, and thoroughly inspect the pump.

Damage: This is one of the most obvious symptoms of cavitation. If you already know that the pump is damaged, you need to remove its filter, open, and inspect it thoroughly. If you find a lot of metal inside the filter, then flush the entire system, and check for damages in other parts, too.

If you notice any of the above-discussed symptoms, the next step would be to identify the causes, and rectify the changes in industrial pumps, otherwise, it may affect other components, too.

Avoid using suction strainers: These are designed to inhibit the ingestion of grime and dirt. However, these strainers do not succeed in their purpose, because they are not designed to entrap large particles. These large particles may get deposited in the flow path, thereby affecting the flow of fluid. The deposition also creates pressure, and produces bubbles, which may lead to cavitation.

Clean the reservoir: A dirty reservoir is one of the most common causes of cavitation. Various types of small and large objects may block the suction tube, and create pressure, thereby causing cavitation.

Use properly sized components: This is one of the important factors of cavitation prevention. If the inlet plumbing is too large, there will be too much liquid flow, which may trigger cavitation. Hence, check with the pump manufacturer to ensure that properly sized components are being used in the pump.

In addition to these preventive steps, you must source hydraulic pumps from a trusted manufacturer or supplier. JM Industrial is one of the industry-leading provider of unused and used industrial process equipment from industry-leading brands. These pumps can be availed at cost-effective prices.

A variety of factors within the system could produce such a vacuum. When fluid enters the hydraulic pump and is compressed, the small air bubbles implode on a molecular level. Each implosion is extremely powerful and can remove material from the inside of the pump until it is no longer functional. Cavitation can destroy brand new pumps in a matter of minutes, leaving signs of physical damage including specific wear patterns. The process of cavitation destroying a hydraulic pump also has a distinctly audible sound similar to a growl.

The good news is that cavitation need not be a common problem in hydraulic systems. A few design flaws are largely responsible for causing cavitation: improper configuration of pump suction lines and the use of suction-line filters or strainers. To prevent these causes of cavitation and ensure the creation of a quality hydraulic system with a long, productive life, seven design elements must be properly executed:

In addition to improper pump suction-line configurations, suction-line filters or strainers can be a leading cause of cavitation. These filters are often placed under the oil reservoir, and thus are rarely serviced properly due to their inconvenient location. With this configuration, the entire reservoir has to be drained and disassembled in order to the reach the filter, so this necessary task is often neglected. As the filter becomes increasingly full of debris over time due to a lack of regular maintenance, not enough fluid will flow to the pump, and cavitation will occur.

Such causes of cavitation can be prevented using a series of correct design practices based on the specific needs and functions of a hydraulic system. Many systems are unique, so an experienced engineer with a firm grasp on each of these concepts must ensure the proper installation and maintenance of a hydraulic system.

Air bubbles in hydraulic fluid first originate is in the reservoir. New oil being introduced into the reservoir can cause turbulent flow, stirring up the oil and introducing air into the fluid, which can lead to cavitation. A correctly designed reservoir tank will prevent this issue.

The size of the tank and the amount of fluid that needs to rest before being extracted depends on the amount of system flow. However, a minimum 4 to 1 tank capacity to flow rate ratio is recommended — four times the oil available in the reservoir at any given time than is needed for extraction to send to the pump. This ensures that the pump will receive clean oil and the oil spends enough time in the reservoir for air bubbles and impurities to work their way out.

Beyond properly designing the reservoir itself, it’s important to include the correct accessories to ensure proper functionality. The breather filter is perhaps the most important accessory for maintaining the correct conditions for the hydraulic fluid in the tank.

When fluid is drawn from the reservoir by the pump, and an equal amount isn"t returned, the oil level will drop. To regulate the pressure and prevent forming a vacuum, air needs to be introduced to the tank to occupy the extra volume created upon removal of the oil. A breather filter performs this function, which helps avoid cavitation.

Incorrect design and configuration of suction lines is the primary cause of cavitation in hydraulic systems. For this reason, it’s crucial to use correct design practices when designing the suction lines, such as using the proper line size, minimizing fittings on the line, and properly sizing the ball valve to handle the amount of flow through the line.

The size of a suction line should be large enough for the liquid’s area to flow through at the correct rate and in the correct amount. Because the pump needs to be constantly supplied with oil, it becomes obvious how a line that’s too small could prevent this essential function. The exact specifications of a suction line in terms of length and width can’t be determined in a general sense — it requires a skilled engineer with a firm grasp of the process to make the correct decision on this specification.

Another best practice to consider when configuring suction lines is to include a lock on the suction ball valve, preventing it from being accidentally closed or left partially closed during the pump’s operation. Shutting off the flow of a suction line during pump operation will have cataclysmic effects on the system.

For example, the oil can be filtered upon entering the reservoir tank rather than when leaving the tank. Or a off-line (kidney loop) filtration system can be used to pull the oil out of the tank, filter it, and reinsert it before it’s extracted and sent to a hydraulic pump. These solutions allow for greater ease of maintenance and lower the chance of system failure.

A key aspect of a hydraulic system is a pump that’s properly sized to handle the flow rate and amount of fluid in the system. Again, this decision must be made by an experienced engineer with a good understanding of the entire process. A pump’s size can be determined by incorporating several variables of the process into a standard equation while also considering unique application conditions.

Another key element within a hydraulic system is to maintain the proper fluid temperature. If the hydraulic fluid gets too cold, it can become too viscous, increasing pressure drop in fluid lines and eventual cavitation in the pump. On the other hand, overheated hydraulic fluid can become too thin, compromising its ability to lubricate the hydraulic pump.

To regulate the temperature of the fluid, electric heating elements can be placed in the reservoir to keep the fluid at the ideal temperature of 110°F. Hydraulic systems often heat themselves naturally, so it’s also important to monitor for temperatures in excess of 110° and provide a heat exchanger or operate the system at reduced capacity.

Most systems use a flooded suction design, meaning that the pump is placed below the oil level to achieve net positive suction. The oil comes out of the reservoir above the location of the pump, which means gravity is used to assist in creating pressure into the pump and suction line. This represents the ideal configuration for a pump in a hydraulic system.

The alternative to this layout is non-flooded suction, in which the pump is placed on top of the tank. This configuration is often used to save space in a system with a limited footprint, but results in several disadvantages. For instance, the pump has to perform the extra work of pulling the oil up against gravity to create a vacuum and then pump the fluid out, which inherently creates restrictions by working against gravity. Also, certain types of pumps will function poorly in a non-flooded suction layout. In these cases, a charge pump can be used to provide positive pressure in the pump suction line.

If each of these design elements is carefully considered while engineering a hydraulic system, the risk of cavitation damaging or destroying hydraulic pumps should decrease significantly. Latest from Valin"s Blog

Although cavitation can occur anywhere in a hydraulic system, it commonly occurs within the suction line of a pump. This will cause excessive noise in the pump – generally a high pitched “whining” sound. However, this excessive noise is only the tip of the iceberg! The real result of this phenomenon is severe pump damage and a decrease in pump life. I have personally seen many instances where a customer was replacing pumps frequently, thinking they were receiving defective pumps from their vendor. In reality, the pump failures were not due to poor pump quality – the failures were occurring because of cavitation.

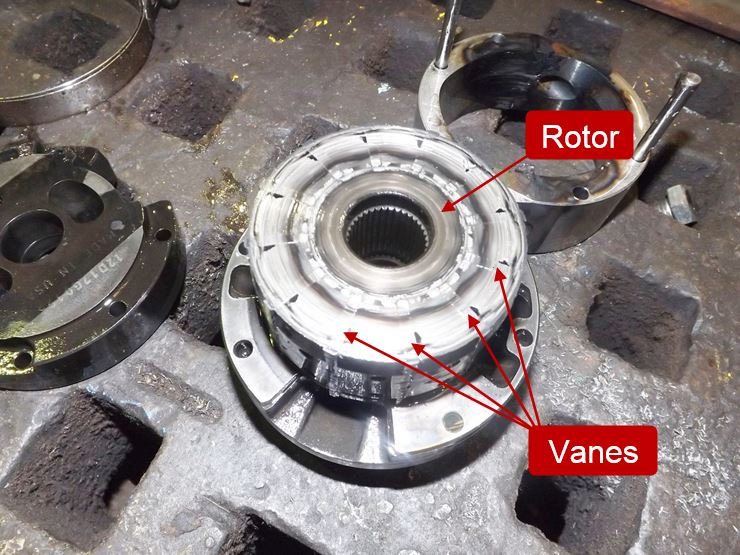

Simply put, cavitation is the formation of vapor cavities in the hydraulic oil. In hydraulic pumps, cavitation will occur any time the pump is attempting to deliver more oil than it receives into the suction (inlet) line. This is commonly referred to as “starvation” and results from a partial vacuum in the suction line. To fully illustrate what is happening when this occurs, we need to discuss vapor pressure. Vapor pressure is the pressure below which a liquid at a given temperature will become a gas, and this pressure varies significantly depending on the liquid. Generally, as the temperature of a liquid rises, the vapor pressure will proportionally increase. Likewise, as the temperature decreases, the vapor pressure will decrease. Most of us know that water will boil (turn to vapor) at 212°F (100°C) at 14.7 PSI (atmospheric pressure at sea level). In other words, the vapor pressure of water at 212°F is 14.7 PSI. If the pressure is reduced, the temperature at which the water boils will be reduced. If the temperature is lowered, the vapor pressure will decrease. In fact, water will boil at room temperature if the pressure is sufficiently reduced! The same principle applies to hydraulic oil, although the vapor pressure will be somewhat different than that of water. The vapor pressure of hydraulic oil is somewhere between 2 and 3 PSI at normal temperatures. In ideal conditions, the pressure in the suction line of the pump will be around 14.7 PSI at sea level. Of course, this pressure decreases with altitude, but sufficient pressure will normally be maintained in the suction line to prevent cavitation of the oil. However, if the pressure in the suction line of the pump is sufficiently reduced to the vapor pressure of the oil, vapor cavities will form. As the oil passes from the suction line to the outlet of the pump, the pressure will increase and the vapor cavities will implode violently. These extremely powerful implosions will cause erosion and premature failure of the pump components. In fact, a brand-new pump can be destroyed in a matter of minutes if the cavitation is severe enough. The picture below shows a rotor and cam ring from a vane pump that had failed due to severe cavitation.

In my 35-plus years of troubleshooting hydraulic components, this is the worst case of cavitation damage I have ever seen. In addition to the usual erosion of the parts, the vanes were actually fused to the rotor slots! Although this is an extreme example, it shows the potential damage to a pump due to cavitation. The good news is that cavitation is preventable and we will look at several conditions that can trigger this phenomenon.

While there are several corrective actions that can be taken to resolve a pump cavitation issue within a hydraulic pump, supercharging, or pressurizing, the pump inlet is probably the easiest and most cost effective way of doing this. There are many different benefits to supercharging (forcing flow into the inlet), which creates an artificial positive head or pressure on the pump inlet, reducing the “suck” a pump must have to get oil into the system. Creating a positive head on the inlet will completely eliminate pump cavitation and increase the longevity of the hydraulic pump. There are different ways in which we can supercharge the pump inlet.

Pump cavitation is one of the most searched topics on fluid power, which is justified, because cavitation is unfortunately an all-too-common cause of pump failure on mobile equipment. Liquids are able to hold dissolved gasses in solution, and the gas saturation level within any liquid is dependent upon the pressure, the temperature and the type of liquid itself, among other things. Cavitation is literally the bubbles spontaneously formed during conditions that prevent the liquid from holding that gas in saturation, such as a drop in relative pressure.

The best example to explain the gas saturation concept and the cavitation principle can be found for a couple bucks at the convenience store—a trusty bottle of soda pop. To ensure the pop is fizzy when it hits your lips, carbon dioxide is super-saturated within the delicious beverage, and pressure maintains that artificial level of fizz until you open the bottle. Upon opening the bottle, you can see cavitation at work, as bubbles seem to form out of nowhere, and other than the fact hydraulic fluid simply has common air dissolved within itself, the principle is the same.

The problem with my example is in trying to translate some harmless bubbles that tickle your taste buds into the damage that can eat away at solid metal. Cavitation bubbles themselves do little damage just floating around in your hydraulic oil, but it’s when the bubbles reach the pressure side of your pump that they do their harm.

Cavitation bubbles would rather form within the imperfections on the surface of the metal parts of your pump, such as the lens plate of a piston pump, or the gear of a gear pump, rather than just popping into existence in the middle of the fluid. The damage from cavitation occurs when the bubbles make their way around to the pressure size of the pump, where they implode under pressure, creating super-hot jets of fluid that pierce the bubble. Because the bubbles are most often located on metal parts, these little implosion jets heat up the surface of the metal, and you end up with little pits that destroy the pump’s efficiency until it just can’t pump at all.

Cavitation is difficult to detect on mobile equipment because of the noise of the engine or the machine itself, but if it ever sounds like someone threw a bag of marbles into your pump, it’s probably a result of cavitation. However, a diesel engine knock sounds not-unlike cavitation, making it difficult to distinguish cavitation noise, especially from inside the cab. Also, cavitation can be unnoticeable even in quiet ambient conditions if it’s not severe, and damage may not be discovered until the pump fails.

Because cavitation is bad, and cannot be corrected or repaired by your dentist, I’m going to give you seven tips on how to avoid cavitation in your hydraulic system. If these tips are heeded, I promise you cavitation will be a thing of your past, like your plaid grunge look or that weekend in Bangkok.

1 – Don’t use a suction strainer. Suction strainers are installed in the reservoir on the suction line of the hydraulic pump. They are intended to protect the pump from ingesting dirt and filth, which should subsequently protect the pump. However, think about the method in which a suction strainer prevents dirt from entering the pump; it collects it across its flow path. Larger particles and other junk get trapped in the suction strainer, but over time it gets clogged.

Most often, maintenance personnel don’t know the power unit even has a suction strainer, so it can get overlooked during routine maintenance, especially because most mobile reservoirs have no clean-out panel. Don’t get me wrong, it could take an easy decade to clog a suction filter, but when it does clog, it will cause slowly increasing levels of cavitation. You might as well have a clamp over the suction hose that you tighten at regular intervals. The biggest problem I have with suction strainers is that they’re redundant anyway if your hydraulic system is designed and maintained well to begin with.

2 – Ensure pumps have flooded suction. A pump can create vacuum at the inlet port to pull up fluid a short distance, but excessive pump head height will cause cavitation. A flooded suction condition uses the force of gravity and atmospheric pressure to push fluid into the pump, rather than the pump having to draw it in. A flooded suction is easy for PTO-mounted pumps because the pumps sit so low in the chassis, but with pumps driven off the engine, you may want to consider mounting your tank high on the machine to compensate for the long run to the front of the truck. With a pump mounted below or to the side of the reservoir, cavitation is nearly impossible unless something catastrophic occurs, like a rag being thrown into the reservoir and blocking the suction line.

3 – Don’t leave rags in the reservoir. It may sound ridiculous for me to offer that as a suggestion, but every hydraulic technician worth their weight in oil counts the number of rags they show up to and leave a job with. The best tools for cleaning out reservoirs are rags, and you will have to trust me when I say that it’s more common than you’d think to leave them in the reservoir. And if you leave a rag in the reservoir, it will most definitely find its way to the suction tube of the pump(s), starving them and causing cavitation.

While we’re at it, be considerate of more than just rags when maintaining a hydraulic machine. I’ve heard of tools, cell phones and dead animals finding their way into reservoirs, not all of which can clog a suction strainer or pump inlet, but their existence there is cause for concern. For a possum to make its way into a tank for a nap, a cover must have been left off, and this lack of consideration for the hydraulic system is unacceptable. Reservoirs are buttoned up for a reason, so I recommend keeping it that way if you care about the health of your machine.

4 – Properly size inlet plumbing. The recommended maximum velocity for suction lines is only a few feet per second, and because the relative action of fluid being “pulled” into the pump already causes a drop in suction pressure, the condition of sucking too much fluid through a small straw will cause cavitation. By simply sizing suction plumbing large enough, especially if you’re running a pump far from the reservoir, you can reduce the chance of cavitation.

5 – Use high quality hydraulic fluid. The quality of hydraulic fluid is often overlooked, and unfortunately, the good stuff is very expensive. Synthetic hydraulic fluid has many properties making it superior to standard dino oil, which has limited capacity to work well outside a narrow window of operating conditions. Speaking on viscosity alone, thicker oil is harder to pump and is more prone to cavitation.

Problems occur during machine start-up, such as on a cold morning, when standard hydraulic fluid is rather thick, making it difficult to pump. If cold and thick oil is not given time to warm before the machine is run at full pressure, cavitation could result. Even if the period of cavitation is short, because oil can heat quickly, the damage can accumulate during every cold start. By switching to synthetic fluid with a high viscosity index, you help ensure cold starts provide little drama. Viscosity index is the quality of oil to maintain its tested viscosity over a wide temperature range, and the bigger the number, the better. So even with a 46 cSt oil which could be prone to cavitating a pump at 20° below if it were normal oil, a high quality oil will still be relatively thin and easy to pump.

6 – Heat your hydraulic oil. Odd as it may sound, because heating oil in mobile machinery is rare, heating the oil before machine start-up can also help prevent cavitation due to cold-related high-viscosity. You wouldn’t fire up your rig and drive off without letting the engine warm up, so the same consideration should be paid to the hydraulic system. Oil doesn’t need much time to come up to temperature in most cases, so just running the pump to circulate oil through the system and operating some low pressure functions could heat up the oil before the serious work begins.

7 – Keep your oil dry. This recommendation comes from a specific example of pump cavitation, which could have been prevented by considering a few of these tips. This brutal past winter broke down more than one hydraulic machine, and this particular example occurred on a half-dozen machines powered by a 12 VDC electric power unit. Excessive water saturation within these power units caused ice to form on the suction strainers, both cavitating the pumps and imploding the strainers.

By following these tips, your chances of experiencing pump cavitation are slim to none. Mobile hydraulic systems already have so much to worry about; creating conditions conducive to cavitation should not be one of them.

Hydraulic cylinder cavitation is a nightmare for any hydraulic system, leading to a cascading series of damaging issues that will eventually destroy critical (and costly) components within your hydraulic system. While most people associate cavitation issues with pumps and motors, cavitation can also be a problem for hydraulic cylinders. In order to minimize or eliminate cavitation damage, knowledge of how it works and what kind of damage it leads to are good starting points. However, the wisest approach to dealing with cavitation issues is to take preventative measures.

The simplest explanation of cavitation is the presence of gas entrapped within bubbles in a liquid. In the case of hydraulic systems and components like pumps or cylinders, the liquid involved is the hydraulic fluid transmitting pressure. In hydraulic cylinders, the pressure transmitted by the fluid is used for linear actuation that can move thousands of pounds at the press of a button. Obviously, very high pressures are involved.

When these bubbles collapse on themselves (or implode), the result is noise, heat, serious surface damage, and a negative impact on efficiency and productivity. Essentially, the bubbles generate a powerful mechanical shock that results in microjets impacting nearby metal. That implosion occurs when the bubbles reach an area of low pressure that causes the vapor within them to condense. The metal begins to wear away in a process known as cavitation erosion, cavitation wear, or cavitation pitting.

Cavitation can also occur when air is trapped within the hydraulic fluid (a phenomenon known as aeration). As pressure increases (e.g., as the rod closes in on the end cap in a hydraulic cylinder) the bubbles violently burst. In a hydraulic cylinder, cavitation most often occurs on the cap side of the piston when it is extending quickly, and especially when it is attempting to stop an over-running load. It also occurs when the rod is pointing downward while supporting a heavy tensile load on the end. Some experts would argue that this is not true cavitation, but its effects are the same.

One of the easiest ways to detect cavitation in a hydraulic cylinder is by sound: when cavitation bubbles implode, you can hear them in the form of an intense rattling sound. You will also notice pitting on the surface of parts affected by cavitation; in the case of hydraulic cylinders, it can be found on the surface of the rod and the inside surface of the cylinder.

Cavitation can lead to multiple problems within a hydraulic system as a whole, as well as hydraulic cylinders. These include accelerated wear of critical surfaces, seal failure, generation of unwanted heat, reduction in hydraulic oil quality, and lubrication issues.

One of the most serious problems caused by cavitation is surface wear, sometimes known as pitting. Keep in mind that the vapor bubbles implode at an almost molecular level, releasing a tremendous amount of force over an incredibly small area. That leads to high stresses — stresses high enough to remove metal from surfaces adjacent to those bubbles. The result is highly accelerated wear in the form of surface pitting and internally generated contamination. The metal particles removed from the surface will stay within the system and can cause the formation of even more cavitation bubbles.

Also, keep in mind that surface finish can be an important factor in many applications, and especially with hydraulic cylinders. When selecting an appropriate seal for a hydraulic cylinder, the surface finish of the rod is critical. If the rod is experiencing pitting due to cavitation, it will cause premature wear of the seal. As the seal begins to wear, hydraulic fluid can leak out (reducing performance) and environmental contaminants such as dust and moisture can make their way inside.

The bubble implosions also lead to high temperatures, sometimes reaching up to 5,000°F. In addition, as the surface is damaged, there will be increased friction as fluid flows over. That friction results in not only system losses and lower efficiency but also unwanted heat generation. This is one of the reasons why excessive heat can also be a strong indicator of cavitation.

Because of the high temperatures that can result from cavitation, the hydraulic fluid is very likely to suffer degradation (an overall reduction in fluid quality). Excessive heat and high temperatures will cause the fluid to age more rapidly than normal, seriously affect the additives present, and reduce the viscosity of the fluid.

The presence of bubbles within the hydraulic fluid can also cause a lack of lubrication, resulting in metal-to-metal contact and premature wear. This type of wear takes on a different form than that resulting directly from cavitation implosion and explosion: it will look like abrasions in a pattern consistent with the movement of the metal parts rather than pitting.

One of the means of preventing cavitation lies in temperature control. If the hydraulic fluid is too viscous, pressure drops will become more of a problem; this increase in viscosity can be the result of hydraulic fluid at a less than ideal temperature. In addition, high temperatures combined with low pressures can also cause cavitation, so care needs to be taken to ensure that the hydraulic fluid is as close as possible to an ideal operating temperature. In some instances, this can be as simple as insulating hydraulic pipes against direct sunlight.

Piping losses can contribute to cavitation and result from issues such as the use of too many fittings, a collapsed pipe liner or suction pipe, a gasket protruding into the pipes, a replacement pump that has too much capacity for the system, or the buildup of solids on the interior surface of the pipes.

Another way to prevent cavitation that is especially applicable to hydraulic cylinders is to prevent air from entering the hydraulic system. For example, hydraulic systems and some components should be bled properly after they are filled (or refilled) to release the air trapped within the system. When additional fluid is added to the system, it should be introduced gently to prevent splashing and agitation — both of which can allow air to be entrained with the fluid. In addition, improperly designed hydraulic reservoirs can inadvertently encourage the entrapment of air within the hydraulic fluid.

The presence of contaminant particles within hydraulic fluid can serve as a starting point for cavitation bubbles to form, so keeping the hydraulic fluid clean and the system free of contaminants can be an excellent starting point. This involves changing hydraulic filters as needed, filtering any hydraulic fluid that enters the system, and addressing leaks as soon as they are detected.

When parts have experienced surface damage due to cavitation, repairs are often a lost cause. For parts with a circular geometry, such as rods and cylinders, the pitting damage is often too deep by the time it is discovered for polishing to work because rods and cylinders must meet very strict surface conditions and geometric tolerances. Unless the damage was discovered quickly, it would be wiser to replace the damaged components. For seals that have been damaged as a side-effect of cavitation, replacing the lip of the seal may be enough.

Cavitation causes so much damage: accelerated surface wear in the form of pitting, premature seal failure, generation of unwanted heat, compromised hydraulic fluid quality, and lack of lubrication leading to additional wear. The best way to deal with cavitation is to take measures to prevent it because once it wreaks havoc on the surfaces of equipment (including hydraulic cylinders), it can be extremely difficult if not impossible to repair. Preventative measures against cavitation are the wisest course of action and can often include basic maintenance principles (e.g., bleeding air out of the system, filtering hydraulic fluid). As soon as hydraulic cylinders start making rattling noises or become hotter than normal, it is time to get them checked out.

At MAC Hydraulics, our highly skilled team can maintain, troubleshoot, and repair hydraulic systems and components, including hydraulic cylinders. Our repair services include replacing seals, polishing rods, and honing tubes — and we also have a 24-hour resealing pick up and delivery service. MAC Hydraulics can manufacture custom cylinders, tubes, and rods with our state-of-the-art fabrication facilities and service any brand equipment from industries including construction, recycling, manufacturing, rental, aviation, and waste handling. If you are experiencing symptoms that are consistent with cavitation, we will help you track down the cause and keep it from happening again.

Many maintenance technicians confuse cavitation and aeration. In fact, aeration is sometimes referred to as pseudo cavitation. While these two conditions have similar symptoms, their causes are entirely different.

Cavitation is the formation and collapse of air cavities in liquid. When hydraulic fluid is pumped from a reservoir, a low-pressure drop occurs in the suction side of the pump. Despite what many people believe, the fluid is not sucked into the pump but rather pushed into it by atmospheric pressure, as shown in the left illustration below.

The movement of the rotating gears leads to a drop in pressure at the suction line. The resulting pressure difference between the reservoir and the pump inlet causes the fluid to move from the higher pressure to the lower pressure. As long as the pressure difference is sufficient and the flow path is clear, the operation goes smoothly, but anything that reduces the inlet flow can create problems. Whenever the pump cannot get as much fluid as it is trying to deliver, cavitation occurs, as shown in the right illustration below.

Hydraulic oil contains approximately 9 percent dissolved air. When a pump does not get enough oil, air is pulled out of the oil. These air bubbles travel into the pump and eventually collapse and implode when they reach an area of relatively high pressure. The ensuing shockwaves produce a steady, high-pitched whining sound and damage to the inside of the pump. In the early stages, the sound goes undetected in loud plants unless an ultrasonic sensor is employed. These sensors can listen to super high frequencies emitted by the pumps, detecting cavitation before it does too much damage.

Any increase in fluid velocity can lead to cavitation. Fluid velocity is inversely proportional to the size of the hydraulic line. Most pumps have a suction line that is larger than the pressure line. This is to keep inlet velocity low, making it very easy for oil to enter the pump. Any blockage, such as a plugged suction strainer or filter, can result in the pump cavitating. A contaminated suction strainer is the most common cause of cavitation simply because it is underneath the oil level in the reservoir.

One of our consultants was recently called to a plant in Georgia that had changed five pumps on a machine within a week. The first thing that was noticed was a high-pitched whining sound, which was heard every 20 to 30 seconds. The millwrights had changed the suction line, and although a suction strainer was shown on the schematic, none was found in the line. The machine was then shut down, and the reservoir drained to be cleaned. Guess what was found in the reservoir? The suction strainer, which had been floating around in the oil, was occasionally blocking the suction pipe to the pump. Had there been early detection of cavitation, the plant could have saved a decent chunk of change on all those pumps.

A plugged breather cap is another common cause of cavitation. It can lead to falling pressure in the reservoir. Suction pressure at the pump must drop very low to compensate for this, creating vapor cavities.

At a plywood plant in Oregon, a hose ruptured on the lathe, which resulted in a loss of 150 gallons of oil in the reservoir. After the hose was changed, the lubrication technician removed one of the breather caps to refill the reservoir. While filling the tank, a shift change occurred, and the second-shift lube tech took over. Once the reservoir was refilled, the lube tech installed a pipe plug on the threads where the breather cap was originally located. The result was that one of the pumps on the unit failed within a few hours after startup due to cavitation. After losing two pumps in 24 hours, the pipe plug on the breather opening was discovered.

Extreme oil temperatures can also cause cavitation. High temperatures allow vapor cavities to form with less of a pressure drop, while low temperatures increase the oil’s viscosity, making it harder for the oil to get into the pump. Most hydraulic systems should not be started up with the oil any colder than 40 degrees F or put under load until at least 70 degrees F.

In addition, cavitation may result if the drive speed is too high for the pump, as the pump tries to deliver more oil than it can get into its suction port. If the pump is positioned so fluid must be lifted a long way from the reservoir, atmospheric pressure may be insufficient to deliver enough fluid to the pump inlet, which can cavitate.

Systems at high altitudes are also susceptible to cavitation, as the available atmospheric pressure may be inadequate. It is for this reason that aeronautic hydraulics must use pressurized reservoirs.

Aeration occurs whenever outside air enters the suction side of the pump. This produces a sound that is more erratic than that of cavitation. The whining noise may be augmented by a sound similar to marbles or gravel rattling around inside the pump. If the oil in the reservoir is visible, you may see foaming. Air in the oil can lead to sluggish system performance and even damage the pump and other components.

One of our consultants was asked to diagnose several pump failures on a system at an automotive manufacturing plant. When he arrived at the unit, he heard an erratic high-pitched sound. He also noticed that there were several fittings in the suction line. He had one of the millwrights fill a bottle with oil and squirt it around all the fittings. When oil was applied to one fitting, the pump momentarily quieted down. This fitting had vibrated loose after 12 years on the machine.

A bad shaft seal on a fixed displacement pump is another common cause of aeration. If you suspect a bad shaft seal, spray some shaving cream around the seal. If it is bad, holes in the shaving cream will develop as air enters the pump.

I was once called to a paper mill where foam came out of the log-kicker reservoir shortly after the fixed displacement pump was started. After performing the shaving cream test, I knew the shaft seal was badly worn. Upon further inspection, I found the pump elastomeric coupling was worn, which resulted in wear on the shaft seal.

Incorrect shaft rotation may not be an issue with all pumps, but some will aerate if they are turned backward. Most pumps have a direction of rotation stamped or located on a sticker on the pump housing. Many times when a pump is rebuilt, this sticker is removed. Always check the part number of the new pump to be installed with the old pump. Often a number or letter will indicate whether it is a right-hand or left-hand rotation. If you are unsure, remove the pump’s outlet line and secure it into a container. Never hold this line, as it could be a hazardous situation. Momentarily jog the electric motor. If the pump is rotating in the correct direction, oil will flow out of the outlet port.

Aeration may also result from a low fluid level. The oil level should never drop more than 2 inches above the suction line. If so, a vortex can form, much like when draining a bathtub. This allows air in the suction line, leading to aeration of the pump.

When troubleshooting hydraulic pump issues, make the visual and sound checks first, as these are the easiest to perform. Remember, aeration and cavitation produce different sounds. Usually you can determine the cause of the problem before the first wrench is turned.

Al Smiley is the president of GPM Hydraulic Consulting Inc., located in Monroe, Georgia. Since 1994, GPM has provided hydraulic training, consulting and reliability assessments to companies in t...

Cavitation is a condition which destroys the effectiveness and efficiency of hydraulic pumps. The attached picture shows classic cavitation in a vane pump. The material of the port plate has literally been carried away downstream with the hydraulic fluid leaving a gap through which oil can leak from the pressure side back to the suction side on the port plate sealing surface. This obviously makes the pump ineffective and the only solution is to remove and replace the complete vane cartridge.

The root cause is a restriction in the pump suction line. The normally entrapped air in the fluid is pulled out by the increased vacuum, forming bubbles in the suction line. When the air is passed from the low pressure side to the high pressure side of the pump. The air bubbles collapse and implode under the pressure, causing tiny explosions and intense heat which damages the metal port plate, sometimes taking the metal to the melting point. This continuous condition produces a high pitched whining noise from the pump and over time, with it’s integrity compromised, the metal is removed away with the hydraulic fluid leaving an empty pocket on the port plate. The constant repetition of this makes the hole grow and at some point renders the pump ineffective.

Aeration of the fluid can also cause cavitation, but in addition to the high pitched whining, there is also a more erratic noise, like a grinding or rumble. Aeration can be caused by a leak on a suction line allowing air to enter or it can also enter externally, like a return line not below the surface of the oil in the reservoir. With aeration you can visually see foam in the oil and the reservoir.

Repairing the pump is not the total solution. Any restrictions, kinked suction hose, plugged suction strainer, or leaks in the suction line or system allowing air in. Need to be remedied or the service life of the pump will be dramatically shortened again.

Across any pumping system there is a complex pressure profile. This arises from many properties of the system: the throughput rate, head pressure, friction losses both inside the pump and across the system as a whole. In a centrifugal pump, for example, there is a large drop in pressure at the impeller’s eye and an increase within its vanes (see Figure 1). In a positive displacement pump, the fluid’s pressure drops when it is drawn, essentially from rest, into the pumping chamber. The fluid’s pressure increases again when it is expelled.

If the pressure of the fluid at any point in a pump is lower than its vapour pressure, it will literally boil, forming vapour bubbles within the pump. The formation of bubbles leads to a loss in throughput and increased vibration and noise. However, when the bubbles pass on into a section of the pump at higher pressure, the vapour condenses and the bubbles implode, releasing, locally, damaging amounts of energy. This can cause severe erosion of pump components.

To avoid cavitation, it is important to match your pump to the fluid, system and application. This is a complex area and you are advised to discuss your application with the pump supplier.

The obvious symptoms of cavitation are noise and vibration. When bubbles of vapour implode they can make a series of bubbling, crackling, sounds as if gravel is rattling around the pump housing or pipework. In addition to the noise, there may be unusual vibrations not normally experienced when operating the pump and its associated equipment.

With centrifugal pumps, the discharge pressure will be reduced from that normally observed or predicted by the pump manufacturer. In positive displacement pumps, cavitation causes a reduction in flow rather than head or pressure because vapour bubbles displace fluid from the pumping chamber reducing its capacity.

Power consumption may also be affected under the erratic conditions associated with cavitation. It may fluctuate and will be higher to achieve the same throughput. Also, in extreme cases, when cavitation is damaging pump components, you may observe debris in the discharged liquid from pump components including seals and bearings.

Under the conditions favouring cavitation, vapour bubbles are seeded by surface defects on metal components within the pump: for example, the impeller of a centrifugal pump or the piston or gear of a positive displacement pump. When the bubbles are subjected to higher pressures at discharge they implode energetically, directing intense and highly focussed shockwaves, as high as 10,000MPa, at the metal surface on which the bubbles had nucleated. Since the bubbles preferentially form on tiny imperfections, more erosion occurs at these points.

When a pump is new, it is more resistant to cavitation because the metal components have few surface imperfections to seed bubble formation. There may be a period of operation before any damage occurs but, eventually, as surface defects accumulate, cavitation damage will become increasingly apparent.

Classic (or classical) cavitation occurs when a pump is essentially starved of fluid (it is also called vaporization cavitation and inadequate NPSH-A cavitation). This can occur because of clogged filters, narrow upstream pipework or restricting (perhaps partially closed) valves. If the pump is fed from a tank, the level of liquid (or pressure above it) may have fallen below a critical level.

In a centrifugal pump, ‘classic’ cavitation occurs at the eye of the impeller as it imparts velocity on the liquid (see Figure 1). In a positive displacement pump, it can happen in an expanding piston, plunger or suction-side chamber in a gear pump. Reciprocating pumps, for example, should not be used in self-priming applications without careful evaluation of the operating conditions. During the suction phase, the pump chamber could fill completely with vapour, which then condenses in a shockwave during the compression phase.

Vane Passing Syndrome, also known as vane syndrome, is a type of cavitation that occurs when the spacing between the vanes of a centrifugal pump’s impeller and its housing is too small, leading to turbulent and restricted flow and frictional heating. The pumped liquid expands as it passes beyond the constriction and cavitation occurs.

Suction recirculation (also called internal recirculation) is a potential problem observed with centrifugal pumps when operated at reduced flow rate. This might occur, for example, when a discharge valve has been left partially closed or when the pump is being operated at a flow below the minimum recommended by the pump manufacturer. Under these conditions, liquid may be ejected from the vanes back towards the suction pipe rather than up the discharge port. This causes turbulence and pressure pulses throughout the pump which may lead to intense cavitation.

Air can be sucked into a pumping system through leaking valves or other fittings and carried along, dissolved in the liquid. Air bubbles may form within the pump on the suction side, collapsing again with the higher pressure on the discharge side. This can create shock waves through the pump.

To avoid cavitation, the pressure of the fluid must be maintained above its vapour pressure at all points as it passes through the pump. Manufacturers of centrifugal pumps specify a property referred to as the Net Positive Suction Head Required or NPSH-R – this is the minimum recommended fluid inlet pressure. The documentation supplied with your pump may contain charts showing how NPSH-R varies with flow.

In fact, NPSH-R is defined as the suction-side pressure at which cavitation reduces the discharge pressure by 3%: a pump is already experiencing cavitation at this pressure. Consequently, it is important to build in a safety margin (about 0.5 to 1m) to take account of this and other factors such as:

Positive displacement pumps require an inlet pressure to be a certain differential greater than the vapour pressure of the fluid to avoid cavitation during the suction phase. This is discussed in terms of Net Positive Inlet Pressure (NPIP) in a similar manner to NPSH for centrifugal pumps. NPSH is measured in feet or meters and NPIP is measured in pressure such as psi or bar. When converted to the same units, NPSH and NPIP are the same. Manufacturers may quote NPIP-R as the recommended inlet pressure and provide charts showing how it varies with pump speed. The available or actual inlet pressure on an operating system is termed NPIP-A.

Cavitation is a potentially damaging effect that occurs when the pressure of a liquid drops below its saturated vapour pressure. Under these conditions it forms bubbles of vapour within the fluid. If the pressure is increased again, the bubbles implode, releasing damaging shockwaves. This can cause severe erosion of components. A common example of cavitation is when a centrifugal pump is starved of feed: vapour bubbles form in the eye of the impeller as it imparts velocity on the liquid and collapse again on the discharge side of the vanes as the fluid pressure increases. This can lead to damage to an impeller’s vanes, seal or bearing. Cavitation can also occur in positive displacement pumps such as gear pumps and plunger pumps.

With a centrifugal pump, ensure that NPSH-A is at least 0.5m greater than NPSH-R during operation. For example, if the pump is fed from a tank, ensure that the level of liquid in the tank (or pressure above it) is sufficient. For a positive displacement pump, make sure that the inlet pressure complies with the manufacturer’s NPIP requirements.

Most modern hydraulic pumps are reliable, robust pieces of equipment that will withstand years of constant service. However, any hydraulic pump can suffer from mechanical issues. Aeration and cavitation are two serious problems that can affect a hydraulic pump, and either problem can cause serious damage if the issue is ignored.

However, it can be difficult to figure out if a malfunctioning pump is suffering from aeration or cavitation, as the two problems tend to produce similar symptoms. Despite these similarities, aeration and cavitation have different causes and require different solutions, so knowing the difference between the two problems is vitally important knowledge for any hydraulic pump user.

All hydraulic pumps contain a small amount of air, which provides space for the pump"s hydraulic fluid to expand into as it heats up. However, excessive amounts of air in a hydraulic system can

8613371530291

8613371530291