apollo 11 mission parts made in china

AS12-48-7134: Apollo 12 astronaut Pete Conrad with the uncrewed Surveyor 3, which had landed on the Moon in 1967. Parts of Surveyor were brought back to Earth by Apollo 12. The camera (near Conrad"s right hand) is on display at the National Air and Space Museum

Third-party evidence for Apollo Moon landings is evidence, or analysis of evidence, about Moon landings that does not come from either NASA or the U.S. government (the first party), or the Apollo Moon landing hoax theorists (the second party). This evidence serves as independent confirmation of NASA"s account of the Moon landings.

In 2008, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) SELENE lunar probe obtained several photographs showing evidence of Moon landings.Apollo 15 astronauts August 2, 1971 during EVA 3 at station 9A near Hadley Rille. On the right is a 2008 reconstruction from images taken by the SELENE terrain camera and 3D projected to the same vantage point as the surface photos. The terrain is a close match within the SELENE camera resolution of 10 metres.

The light-colored area of blown lunar surface dust created by the lunar module engine blast at the Apollo 15 landing site was photographed and confirmed by comparative analysis of photographs in May 2008. They correspond well to photographs taken from the Apollo 15 Command/Service Module showing a change in surface reflectivity due to the plume. This was the first visible trace of crewed landings on the Moon seen from space since the close of the Apollo program.

As with SELENE, the Terrain Mapping Camera of India"s Chandrayaan-1 probe did not have enough resolution to record Apollo hardware. Nevertheless, as with SELENE, Chandrayaan-1 independently recorded evidence of lighter, disturbed soil around the Apollo 15 site.

In April 2021 the ISRO Chandrayaan-2 orbiter captured an image of the Apollo 11 Lunar Module Eagle descent stage. The orbiter"s image of the Apollo landing site was released to the public in a presentation on September 3, 2021.

China"s second lunar probe, Chang"e 2, which was launched in 2010 is capable of capturing lunar surface images with a resolution of up to 1.3 metres. It claims to have spotted traces of the Apollo landings and the lunar Rover, though the relevant imagery has not been publicly identified.

Aside from NASA, a number of entities and individuals observed, through various means, the Apollo missions as they took place. On later missions, NASA released information to the public explaining where third party observers could expect to see the various craft at specific times according to scheduled launch times and planned trajectories.

The Soviet Union monitored the missions at their Space Transmissions Corps, which was "fully equipped with the latest intelligence-gathering and surveillance equipment".Vasily Mishin, in an interview for the article "The Moon Programme That Faltered", describes how the Soviet Moon programme dwindled after the Apollo landing.

Dr. Michael Moutsoulas at Pic du Midi Observatory reported an initial sighting around 17:10 UT on December 21 with the 1.1-metre reflector as an object (magnitude near 10, through clouds) moving eastward near the predicted location of Apollo 8. He used a 60 cm refractor telescope to observe a cluster of objects which were obscured by the appearance of a nebulous cloud at a time which matches a firing of the service module engine to assure adequate separation from the S-IVB. This event can be traced with the Apollo 8 Flight Journal, noting that launch was at 0751 EST or 12:51 UT on December 21.

During the Apollo 10 mission The Corralitos Observatory was linked with the CBS news network. Images of the spacecraft going to the Moon were broadcast live.: p. 17

At Jodrell Bank Observatory in the UK, the telescope was used to observe the mission, as it was used years previously for Sputnik.were tracking the uncrewed Soviet spacecraft Luna 15, which was trying to land on the Moon.

Larry Baysinger, a technician for WHAS radio in Louisville, Kentucky, independently detected and recorded transmissions between the Apollo 11 astronauts on the lunar surface and the Lunar Module.Capsule Communicator (CAPCOM) in Houston, Texas, and the associated Quindar tones heard in NASA audio and seen on NASA Apollo 11 transcripts. Kaminski and Baysinger could only hear the transmissions from the Moon, and not transmissions to the Moon from the Earth.

Apollo 13 was intended to land on the Moon, but an oxygen tank explosion resulted in the mission being aborted after trans-lunar injection. It flew by the Moon but did not orbit or land.

Rachel, Chabot Observatory"s 20-inch refracting telescope, helps bring Apollo 13 and its crew home. One last burn of the lunar lander engines was needed before the crippled spacecraft"s re-entry into the Earth"s atmosphere. In order to compute that last burn, NASA needed a precise position of the spacecraft, obtainable only by telescopic observation. All the observatories that could have done this were clouded over, except Oakland"s Chabot Observatory, where members of the Eastbay Astronomical Society had been tracking the Moon flights. EAS members received an urgent call from NASA Ames Research Station, which had ties with Chabot"s educational program since the 60s, and they put the Observatory"s historic 20-inch refractor to work. They were able to send the needed data to Ames, and the Apollo crew was able to make the needed correction and to return safely to Earth on this date in 1970.

Paul Wilson and Richard T. Knadle, Jr. received voice transmissions from the Command/Service Module in lunar orbit on the morning of August 1, 1971. In an article for

Bochum Observatory tracked the astronauts and intercepted the television signals from Apollo 16. The image was re-recorded in black and white in the 625 lines, 25 frames/s television standard onto 2-inch videotape using their sole quad machine. The transmissions are only of the astronauts and do not contain any voice from Houston, as the signal received came from the Moon only. The videotapes are held in storage at the observatory.

A total of 382 kilograms (842 lb) of Moon rocks and dust were collected during the Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, 16 and 17 missions.Antarctica.oldest Earth rocks, which are from the Hadean eon and dated 3.8 to 4.3 billion years ago. The rocks returned by Apollo are very close in composition to the samples returned by the independent Soviet Luna programme.margin of error of plus or minus 6 million years. The test was done by a group of researchers headed by Alexander Nemchin at Curtin University of Technology in Bentley, Australia.

Plot of arrival time of photons (Y axis) for each of many laser pulses sent to the Moon (X axis). This data, along with similar data from the other landing sites, shows there are man-made objects on the Moon in the locations of the Apollo landings. Credit: The APOLLO (Lunar Laser Ranging) Collaboration

The image on the left shows what is considered some of the most unambiguous evidence. This experiment repeatedly fires a laser at the Moon, at the spots where the Apollo landings were reported. The dots show when photons are received from the Moon. The dark line shows that a large number come back at a specific time, and hence were reflected by something quite small (well under a metre in size). Photons reflected from the surface come back over a much broader range of times (the whole vertical range of the plot corresponds to only 18 metres or so in range). The concentration of photons at a specific time appears when the laser is aimed at the Apollos 11, 14 or 15 landing sites; otherwise the expected featureless distribution is observed.

Strictly speaking, although retroreflectors left by Apollo astronauts are strong evidence that human-manufactured artifacts currently exist on the Moon and that human visitors left them there, they are not, on their own, conclusive evidence. Uncrewed missions are known to have placed such objects on the Moon, albeit not before 1970. Smaller retroreflectors were carried by the uncrewed landers Lunokhod 1 was unknown for nearly 40 years but it was rediscovered in 2010 in photographs by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and its retroreflector is now in use. Both the United States and the USSR had the capability to soft-land objects on the surface of the Moon for several years before that. The USSR successfully landed its first uncrewed probe (Luna 9) on the Moon in February 1966, and the United States followed with Surveyor 1 in June 1966, but no uncrewed landers carried retroreflectors before Lunokhod 1 in November 1970. The retroreflectors are proof that human-made probes reached the exact locations of the Apollo 11, 14, and 15 landing sites at exactly the same time as those missions.

In October-November 1977, the Soviet radio telescope RATAN-600 observed all five transmitters of ALSEP scientific packages placed on the Moon surface by all Apollo landing missions excluding Apollo 11. Their selenographic coordinates and the transmitter power outputs (20 W) were in agreement with the NASA reports.

Images taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission beginning in July 2009 show the six Apollo Lunar Module descent stages, Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package (ALSEP) science experiments, astronaut footpaths, and lunar rover tire tracks. These images are the most effective proof to date to rebut the "landing hoax" theories.LROC Science Operations Center at Arizona State University, along with many other academic groups.German Aerospace Center, Berlin, are not located in the US, and are not funded by the US government.

After the images shown here were taken, the LRO mission moved into a lower orbit for higher resolution camera work. All of the sites have since been re-imaged at higher resolution.

Further imaging in 2012 shows the shadows cast by the flags planted by the astronauts on all Apollo landing sites. The exception is that of Apollo 11, which matches Buzz Aldrin"s account of the flag being blown over by the lander"s rocket exhaust on leaving the Moon.

Comparison of the Apollo 17 landing site between the original 16 mm footage shot from the LM window during ascent in 1972, and the 2011 lunar reconnaissance orbiter image of the Apollo 17 landing site. From the EEVdiscover video.

AS16-123-19657: Long-exposure photograph taken from the surface of the Moon by Apollo 16 using the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph. It shows the Earth with the correct background of stars (some labeled)

Long-exposure photos were taken with the Far Ultraviolet Camera/Spectrograph by Apollo 16 on April 21, 1972, from the surface of the Moon. Some of these photos show the Earth with stars from the Capricornus and Aquarius constellations in the background. The European Space Research Organisation"s TD-1A satellite later scanned the sky for stars that are bright in ultraviolet light. The TD-1A data obtained with the shortest passband is a close match for the Apollo 16 photographs.

This section contains reports of the lunar missions from facilities that had significant numbers of non-NASA employees. This includes facilities such as the Deep Space Network, which employed (and still employs) many local citizens in Spain and Australia, and facilities such as the Parkes Observatory, which were hired by NASA for specific tasks, but staffed by non-NASA personnel.

The NASA Manned Space Flight Network (MSFN) was a worldwide network of stations that tracked the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo and Skylab missions. Most MSFN stations were only needed during the launch, Earth orbit and landing phases of the lunar missions, but three "deep space" sites with larger antennas provided continuous coverage during the trans-lunar, trans-Earth and lunar mission phases. Today, these three sites form the NASA Deep Space Network: the Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex near Goldstone, California; the Madrid Deep Space Communication Complex near Madrid, Spain; and the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, adjacent to the Tidbinbilla Nature Reserve, near Canberra, Australia.

Although most MSFN stations were NASA-owned, they employed many local citizens. NASA also contracted the Parkes Observatory in New South Wales, Australia, to supplement the three deep space sites, most famously during the Apollo 11 EVA as documented by radio astronomer John SarkissianCommonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), a research agency of the Australian government. It would have been relatively easy for NASA to avoid using the Parkes Observatory to receive the Apollo 11 EVA television signals by scheduling the EVA at an earlier time when the Goldstone station could provide complete coverage.

The Madrid Apollo Station, now part of the Deep Space Network, built in Fresnedillas, near Madrid, Spain, tracked Apollo 11.Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial.

"The "halo" area around Apollo 15 landing site observed by Terrain Camera on SELENE (KAGUYA)" (Press release). Chōfu, Tokyo: Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. May 20, 2008. Archived from the original on 13 March 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

drbuzz0 (November 7, 2009). "Apollo 15: Confirmed Times Three". Depleted Cranium (Blog). Steve Packard. Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

Swaim, Dave (December 22, 1968). "Apollo 8 Mission Leaves Earth on Historic Voyage". Independent Star News. Pasadena, California. p. 1. Retrieved May 9, 2013. The TLI firing was begun at 7:41 a.m. (PST) while the craft was over Hawaii, and it was reported there that the burn was visible from the ground.

Cantù, A. M.; Felli, M.; Landini, M.; Tofani, G. (1967). "1967MmSAI..38..539C Page 539". Memorie della Societa Astronomica Italiana. 38: 539. Bibcode:1967MmSAI..38..539C. Retrieved 2021-11-11.

Kantrowitz, Arthur (1 April 1971). "The Relevance of Space (inset Apollo 14)". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Educational Foundation for Nuclear Science, Inc.: 33. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

Kaminski, H. (October–November 1972). "Sternwarte Bochum beobachtet US-Apollo-Mondexperimente" [Bochum Observatory Observed U.S. Apollo Moon Experiments] (PDF). Neues von Rohde & Schwarz (in German). Vol. 57. Munich: Rohde & Schwarz. pp. 24–27. Retrieved April 25, 2011.

Laul, JC; Schmitt, RA (1973). "Chemical composition of Luna 20 rocks and soil and Apollo 16 soils". Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 37 (4): 927–942. Bibcode:1973GeCoA..37..927L. doi:10.1016/0016-7037(73)90190-7.

Hautaluoma, Grey; Freeberg, Andy (July 17, 2009). Garner, Robert (ed.). "LRO Sees Apollo Landing Sites". NASA. Retrieved July 18, 2007. NASA"s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, or LRO, has returned its first imagery of the Apollo Moon landing sites. The pictures show the Apollo missions" lunar module descent stages sitting on the moon"s surface, as long shadows from a low sun angle make the modules" locations evident.

This is a partial list of artificial materials left on the Moon, many during the missions of the Apollo program. The table below does not include lesser Apollo mission artificial objects, such as a hammer and other tools, retroreflectors, Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Packages, or the commemorative, artistic, and personal objects left by the twelve Apollo astronauts, such as the United States flags, the commemorative plaques attached to the ladders of the six Apollo Lunar Modules, the silver astronaut pin left by Alan Bean in honor of Clifton C. Williams whom he replaced, the Bible left by David Scott, the Apollo 15, the Apollo 11 goodwill messages disc, or the golf balls Alan Shepard hit during an Apollo 14 moonwalk.

Five S-IVB third stages of Saturn V rockets from the Apollo program crashed into the Moon, and are the heaviest human-made objects on the lunar surface. Humans have left over 187,400 kilograms (413,100 lb) of material on the Moon. Besides the 2019 Chinese rover lunar laser ranging experiments left there by the Apollo 11, 14, and 15 astronauts, and by the Soviet Union"s Lunokhod 1 and Lunokhod 2 missions.

Portions recovered by Apollo 12 in 1969: it returned about 10 kilograms (22 lb) of the Surveyor 3"s original landing mass of 302 kilograms (666 lb) to Earth to study the effects of long term exposure.

The ascent stage of Apollo 10 was commanded to fire its engine, left lunar orbit and entered solar orbit. The ascent stage of Apollo 11 was left in orbit and thereafter its orbit possibly decayed and it crashed onto the Moon at an unknown location. The Apollo 16 ascent stage failed to crash onto moon when commanded and it decayed from orbit at a later date and also crashed at an unknown location. The ascent stages of the remaining successful missions (Apollo 12, 14, 15, and 17) were each deliberately crashed onto the Moon. Apollo 13"s complete Apollo Lunar Module re-entered Earth"s atmosphere after having served as a lifeboat during the aborted mission.

The country’s Chang’e-5 spacecraft gathered as much as 4.4 pounds of lunar samples from a volcanic plain known as Mons Rümker in a three-week operation that underlined China’s growing prowess and ambition in space. It was China’s most successful mission to date.

The Chinese are eager to flaunt their technical skills and explore the solar system. Like the United States, the country has a broader goal to establish a lunar base that could exploit its potential resources and serve as a launching pad for more ambitious missions.

Some hope that a competition between China and the United States could change to cooperation. But NASA is currently limited from directly working with the Chinese space agency or Chinese-owned companies. That provision was inserted in 2011 into the law financing NASA by Frank Wolf, then a Republican congressman from Virginia, to punish China for its human rights record and to protect American aerospace technology.

Although the law does not prevent non-NASA scientists from working with Chinese counterparts, it does prevent Chinese scientists from looking at the moon rocks that NASA astronauts brought back during the Apollo missions, and China may well return that snub.

But while China takes its time with longer-term space goals, the successful Chang’e-5 mission took off only last month, and its speedy return with lunar samples provided almost instant gratification. It required feats of engineering and execution that China has never attempted before.

Not long after arriving in lunar orbit, Chang’e-5 split into two parts, an orbiter and a lander that reached the surface on Dec. 1. It then scooped up and drilled for samples that the spacecraft returned to lunar orbit and then ultimately back to Earth. The lander also lifted a small Chinese flag.

China envisions its moon missions as more than demonstrations of its space technology and national pride. It envisions the moon as a base — robotic at first, then perhaps a human outpost — that will support space exploration in the decades to come.

After conducting three successful robotic lunar missions between 2007 and 2013, China’s blossoming moon exploration program appears to be entering a slower, more tentative phase. The nation had intended to loft its Chang’e 5 spacecraft on a Long March 5 rocket by the end of the year, to land on and retrieve samples from the lunar surface. But a July launch failure of another Long March 5 has seemingly deferred those efforts for months—perhaps years. With the Chang’e 5 sample-return mission now unofficially but apparently on hold, China may instead next use a different rocket booster to send a lunar lander and rover to the moon’s far side in 2018. That separate mission is called Chang’e 4, and was built as a backup to China’s Chang’e 3 lander and Yutu moon rover that successfully reached the moon in December 2013.

Although disappointing for the China National Space Administration (CNSA), which hopes to eventually dispatch many more robotic probes to the moon and perhaps even human missions to its water ice–rich polar regions, the delay and reshuffling could ultimately prove beneficial by allowing more time for international collaboration to emerge on lunar science and exploration.

Many other nations—including, perhaps, the U.S.—are gearing up for their own visits to the moon in coming years, offering China plentiful potential partners in lunar exploration. More than 40 years have passed since NASA’s Apollo astronauts retrieved hundreds of pounds of moon rocks from their sorties on the lunar surface. And the last time any samples at all were returned to Earth was 1976, via some 170 grams sent back from the Soviet Luna 24 lander. New samples could be a scientific bonanza for the global lunar research community, but only if China proves willing to share.

Similarly, China and Russia are on track to sign a bilateral agreement on joint space exploration from 2018 to 2022, with an emphasis on future missions to the moon and other deep-space destinations. “The Chinese clearly have a very ambitious program of lunar exploration operating on what can only be described as an ‘aggressive’ timescale,” suggests Ian Wright, a professor of planetary sciences at The Open University in the U.K. who also attended the lunar samples workshop. “What is not clear to me, at least, is how much of this [program] still needs [governmental] approval. But, I would put money on it all happening at some point,” Wright says. Although China’s lunar sample return might be delayed, he notes, the nation’s work on a facility to store and study those eventual samples is progressing at a rapid pace.

For now, the greatest unknown may be the new launch date for Chang’e 5. According to Xingguo Zeng, a research assistant in the Lunar and Deep Space Exploration Division at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ National Astronomical Observatories, the mission could launch as early as next year, but “the specific day is still unknown.”

Chang’e 5 is composed of four parts: the orbiter, lander, ascender and Earth-reentry module. The lander and ascender form a combination that would touch down on the lunar surface to prospect and collect samples using a drill and mechanical arm. Once the samples are secured, the ascender would blast off to transfer the moon material to the reentry capsule waiting in lunar orbit. The capsule would then rocket back to Earth, reentering the atmosphere and deploying parachutes to safely deposit its precious cargo back on terra firma. Finally, the samples would be transported to Beijing for processing, storage and study in a facility built and operated by the National Astronomical Observatories.

The hunger for new samples comes from the fact that all the older returned lunar material came from just a handful of scattered sites that offer a woefully incomplete picture of the moon’s deep history. Scientists still lack a thorough understanding of exactly how Earth’s most intimate celestial companion formed billions of years ago. Chang’e 5 could help change that, by returning samples from Mons Rümker, a region in the moon’s Oceanus Procellarum crater thought to be rich in igneous rock much younger than the samples returned by the Apollo astronauts. Oceanus Procellarum is a prime example of a lunar “mare” (Latin for “sea”), a vast expanse of dark basalt that 17th-century astronomers mistook for a body of water on the moon.

“[Mons Rümker] is a great target for a sample-return mission as we have no Apollo samples from mare[s] less than roughly three billion years old, says Mark Robinson, a leading lunar expert at Arizona State University. Robinson is also the principal investigator for the camera system on NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been mapping the moon since 2009. “Hopefully, those young mare[s] are their target,” he says. Returning samples from that area would be “an awesome science return,” he adds, not only important for understanding the evolution of lunar volcanism over time but also for calibrating the moon’s exact age, which in turn helps constrain the ages of Mercury, Mars, Venus and other rocky bodies in the solar system.

To visit the underground facility you enter a ground-level elevator “and press minus 3,” says Blewett, who recalls seeing convoys of trucks delivering glove boxes and other equipment to the lab. “I can’t recall hearing or reading about plans for sharing the samples with the international community,” he says. If, however, the data-sharing follows the practices of past Chinese lunar missions, “there may be two proprietary periods for the data.” Scientists directly involved in the mission would have prioritized access, he says, followed by other outside researchers in China. Eventually, data were made available to researchers outside China via an internet database. A similar protocol might be used for data from Chang’e 5’s returned samples, he says.

Still, direct access to China’s cache of lunar materials is caught up in U.S. politics. At present the space agency and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) are both prohibited from directly working with China due to a clause first inserted in 2011 federal budget legislation by Rep. Frank Wolf (R–Va.), who at the time chaired the House Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies. Wolf is now retired and left Congress in 2015 but a version of the “Wolf Amendment” remains in force to this day, and prevents NASA and OSTP from “bilateral” collaborations with China without explicit authorization from Congress. “Therefore, I expect that China will not be eager to share samples directly with U.S. scientists,” Blewett says. There are, he adds, various loopholes to circumvent Wolf’s restrictions: Bilateral U.S.–China collaborations are explicitly prohibited, but “multilateral” projects are not, allowing U.S. researchers to work on NASA-funded work with scientists in China—provided there are researchers from additional countries also involved. Furthermore, neither the National Science Foundation nor the National Institutes of Health are under similar restrictions on joint U.S.–China research, offering additional avenues for federally funded collaboration. Which means that, one way or another, the U.S. planetary science community would likely find a way to gain access to any new Chinese lunar samples from China.

“This is an exciting time for lunar science, and it is a shame that politics prevents U.S. scientists from being directly involved, says Clive Neal, a lunar scientist at the University of Notre Dame. “Likewise, it is a shame that Chinese scientists cannot request Apollo samples. Scientists will, however, continue to work together in order to better understand the moon, and hopefully bridge the gap politicians can’t.”

One intriguing proposal to boost the chances for U.S. access to China’s forthcoming samples comes from one of the last living moonwalkers, the Apollo 11 astronaut Buzz Aldrin, who was the second human to set foot on the lunar surface. Aldrin wants to arrange a lunar rock swap, of sorts—something similar to an arrangement made between the U.S. and the Soviet Union in the 1970s, when both nations shared samples from their respective lunar missions. “Sharing lunar samples between nations is good for science,” he says. “It’s good for country-to-country cooperation. And furthermore, it helps focus the exploration agenda of the U.S. and China as we return to the moon as a proving ground for sending crews to distant Mars. I believe it’s time to seek avenues of space cooperation with China—and exchanging specimens brought back from the moon is one of them.”

There is, in fact, already a historical precedent for sharing lunar samples with China: In 1970 Pres. Richard Nixon gave some of Apollo 11’s moon rocks to China as a goodwill gift. China was among 135 foreign countries that received tiny flakes of lunar material. But this meager amount barely scratches the surface of Apollo’s trove, the bulk of which remains carefully curated at a facility in NASA’s Johnson Space Center. All in all, between 1969 and 1972 the six Apollo missions brought back 842 pounds of lunar rocks, core samples, pebbles, sand and dust from the lunar surface. The Apollo expeditions returned 2,200 separate samples from six different exploration sites on the moon. Perhaps offering more of Apollo’s mother lode to China would encourage reciprocal sharing.

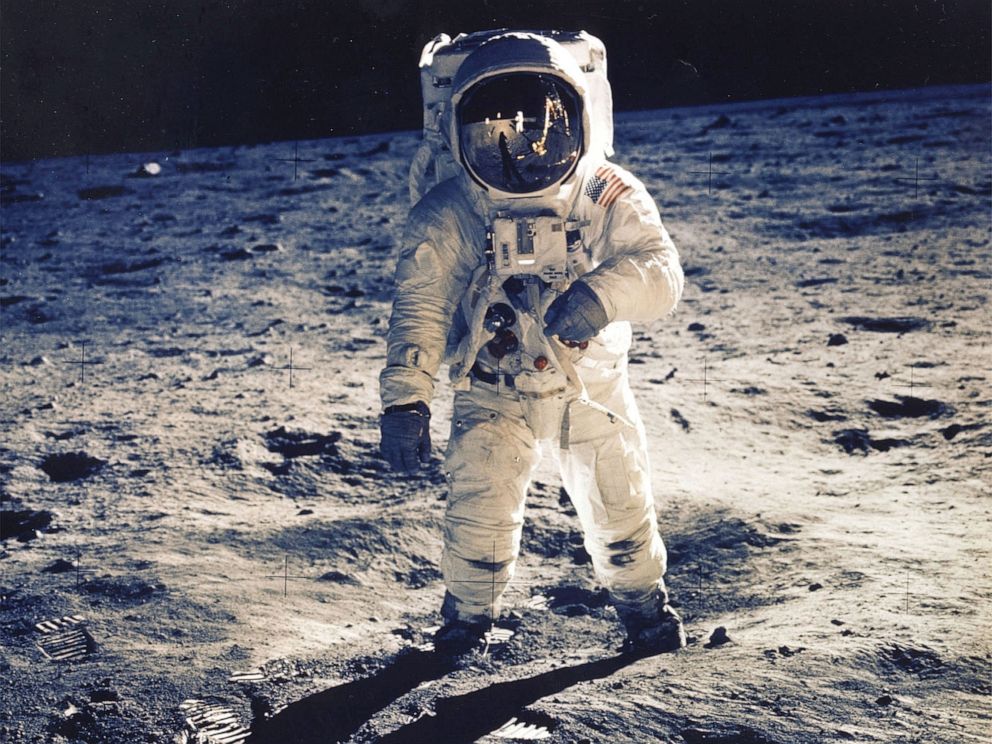

The US planted the first flag on the Moon during the manned Apollo 11 mission in 1969. Five further US flags were planted on the lunar surface during subsequent missions up until 1972.

The first flag was said by astronaut Buzz Aldrin to have been placed too close to the Apollo lunar module and was, he said, probably blown away when the module blasted off.

The Chinese flag is 2m wide and 90cm tall and weighs about a kilogram. All parts of the flag have been given features such as protection against cold temperatures, project leader Li Yunfeng told the Global Times.

China"s national flag was seen on the Moon during its first lunar landing mission, Chang"e-3 in photographs taken by the lander and rover of each other. The Chang"e-4 lander and rover brought the flag to the dark side of the moon in 2019.

On the evening of January 2, a Chinese lander named for an ancient moon goddess touched down on the lunar far side, where no human or robot has ever ventured before. China"s Chang"e-4 mission launched toward the moon on December 7 and entered orbit around our cosmic companion on December 12. Now, the spacecraft has alighted onto the lunar surface.

The Chang"e-4 probe is the latest mission sent to the moon by CNSA, the Chinese space agency. The first two lunar missions were orbiters, and the third was a lander-rover combo that successfully landed on the near side of the moon in 2013. Chang"e-4 consists of a lander and a rover, as well as a relay satellite, and its goal is to set down gently on the lunar far side. (See stunning pictures from the Chang"e-3 mission.)

It"s difficult to maintain communication with Earth during a far-side landing, because the moon itself blocks radio contact. When Apollo astronauts orbited to the moon"s far side, they were totally cut off from the rest of humankind.

The Chang"e-4 mission has gotten around this problem with a relay satellite. In May 2018, CNSA launched a satellite called Queqiao into orbit around L2, a neutral point beyond the moon where the gravity of Earth and the moon cancel out the centripetal force of an object stationed there, effectively allowing it to park in place. Since Queqiao always has good sight lines to both Earth and the lunar far side, it will bridge the gap between mission control and the Chang"e-4 lander.

Many of the instruments aboard Chang"e-4 are replicas of ones that flew on Chang"e-3, the mission"s predecessor. These hand-me-downs include several cameras, including the one that Chang"e-3 used to take awe-inspiring panoramas of the lunar surface. Chang"e-4 also comes equipped with radar that can penetrate the moon"s surface.

Unlike Chang"e-3, Chang"e-4 is carrying a "lunar biosphere" experiment containing plant seeds and silkworm eggs, as well as a low-frequency radio spectrometer that will let researchers study the sun"s high-energy atmosphere from afar. This instrument has an extra trick: By pairing it with an instrument on board Queqiao, Chinese researchers can use the two as a radio telescope. The moon"s far side is ideal for radio astronomy, since the moon blocks noise from Earth"s ionosphere and human radio transmissions.

Not all of Chang"e-4"s instruments are Chinese. The mission"s scientists teamed up with German researchers to install a particle detector on the lander, and Swedish researchers put an ion detector on the rover. The radio-telescope instrument on Queqiao is a joint Dutch-Chinese effort.

There are models for countries cooperating in space even when tensions persist back on Earth. During the Cold War, the U.S. worked with the U.S.S.R. for projects such as the Apollo-Soyuz mission. Some observers, such as Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins, even advocated for the U.S. and the Soviet Union to embark on a joint Mars mission. (Read Collins"s plan in the November 1988 issue of National Geographicmagazine.)

China has big plans for its lunar exploration program. Its next mission, Chang"e-5, will attempt to land on the moon"s surface and return samples to Earth. If China is successful, it would be just the third country to send stuff back from the moon, and the second country to do so with robots. While details are slim, Chinese researchers outlining the country"s post-2020 moon plans have also discussed sending humans to the moon and building a base there.

“If at some point we can marshal the world"s resources to do these things, we"re going to be a lot better off,” says Kurt Klaus, the commercial lead for the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group, which supports NASA"s moon missions. “But how far away we are from that, I don"t know.”

Three days after leaving the Moon, on July 24, 1969, they splashed down in Earth"s oceans, successfully completing their return trip. But during Apollo 11"s return to Earth, a serious anomaly occurred: one that went undetected until after the crew returned to Earth. Uncovered by Nancy Atkinson in her new book, Eight Years to the Moon, this anomaly could have led to a disastrous ending for astronauts Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins. Here"s the story you"ve never heard.

This NASA image was taken on July 16, 1969, and shows some of the thousands of people who camped out... [+]on beaches and roads adjacent to the Kennedy Space Center to watch the Apollo 11 mission Liftoff aboard the Saturn V rocket. Four days later, humanity would take our first footsteps on another world. Four days after that, the astronauts successfully returned to Earth, but that was not a foregone conclusion. (NASA / AFP / Getty Images)Getty

According to our records, the flight plan of Apollo 11 went off without a hitch. Chosen as the mission to fulfill then-President Kennedy"s goal of performing a crewed lunar landing and successful return to Earth, the timeline appeared to go exactly as planned.

On July 16, 1969, the Saturn V rocket responsible for propelling Apollo 11 to the Moon successfully launched from Cape Kennedy. (Modern-day Cape Canaveral.)

Only July 17, the first thrust maneuver using Apollo"s Service Propulsion System (SPS) was made, course-correcting for the journey to the Moon. The launch and this one corrective burn were so successful that the other three scheduled SPS maneuvers were not even needed.

This artist"s concept shows the Command Module undergoing re-entry in 5000 °F heat. The Apollo... [+]Command/Service Module was used for the Apollo program which landed astronauts on the Moon between 1969 and 1972. An ablative heat shield on the outside of the Command Module protected the capsule from the heat of re-entry (from space into Earth"s atmosphere), which is sufficient to melt most metals. During re-entry, the heat shield charred and melted away, absorbing and carrying away the intense heat in the process. (Heritage Space/Heritage Images/Getty Images)Getty

Successful re-entries after a journey to the Moon had already taken place aboard NASA"s Apollo 8 and Apollo 10 missions, and Apollo 11 was expected to follow the same procedures. At the danger of becoming complacent, this step, in many ways, already seemed like old hat to many of those staffing the Apollo 11 mission.

This schematic drawing shows the stages in the return from a lunar landing mission. The Lunar Module... [+]takes off from the Moon and docks with the Command and Service Module. The Command Module then separates from the Service Module, which jettisons its fuel and accelerates away. The Command Module then re-enters the Earth"s atmosphere, before finally parachuting down to land in the ocean. (SSPL/Getty Images)Getty

Although there are no known photographs of the Apollo 11 Command Module descending towards... [+]splashdown in the Pacific Ocean, all of the crewed Apollo missions ended in similar fashion: with the Command Module"s heat shield protecting the astronauts during the early stages of re-entry, and a parachute deploying to slow the final stages of descent to a manageable speed. Shown here, Apollo 14 is about to splash down in the oceans, similar to the prior missions such as Apollo 11. (SSPL/Getty Images)Getty

Both the Command Module and the Service Module from Apollo 11 followed the same re-entry trajectory,... [+]which could have proved fatal to the astronauts aboard the Command Module if a collision of any type had occurred. It was only through luck that such a catastrophe was avoided.NASA

The crew of Apollo 11 — Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, and Buzz Aldrin — in the Mobile Quarantine... [+]Facility after returning from the surface of the Moon. The U.S.S. Hornet successfully recovered the astronauts from the Command Module after splashdown, where the crew was greeted by President Nixon, among others. (MPI/Getty Images)Getty

There was a fault in how the Service Module was configured to jettison its remaining fuel: a problem that was later discovered to have occurred aboard the prior Apollo 8 and Apollo 10 missions as well. Instead of a series of thrusters firing to move the Service Module away from the Command Module, shifting it to a different trajectory and eliminating the possibility of a collision, the way the thrusters actually fired put the entire mission at risk.

In the aftermath of Apollo 11, investigators determined that the proper procedure for avoiding contact would be to properly time the firing of both the roll jets and the Minus X jets, which would lead to a 0% probability of contact between the two spacecrafts. This might seem like an extremely small point — to have the Minus X jets cut out after a certain amount of time firing as well as the roll jets — but you must remember that the spacecraft is full of moving parts.

If, for example, the fuel were to slosh around after the Service Module and the Command Module separated, that could lead to a certain window of uncertainty in the resultant trajectory. Without implementing the correct procedure for firing the various jets implemented, the safe return of the Apollo 11 astronauts would have to come down to luck.

This NASA picture taken on April 17, 1970, shows the Service Module (codenamed "Odyssey") from the... [+]Apollo 13 mission. The Service Module was jettisoned from the Command Module early, and the damage is clearly visible on the right side. This was to be the third crewed Apollo mission to land on the Moon, but was aborted due to the onboard explosion. Thankfully, the flaw in the jettison controller had been fixed, and the Service Module posed no risk to the astronaut-carrying Command Module from Apollo 13 onwards. (AFP/Getty Images)Getty

Fortunately for everyone, they did get lucky. During the technical debriefing in the aftermath of Apollo 11, the fly-by of the Service Module past the Command Module was noted by Buzz Aldrin, who also reported on the Service Module"s rotation, which was far in excess of the design parameters. Engineer Gary Johnson hand-drew schematics for rewiring the Apollo Service Module"s jettison controller, and the changes were made just after the next flight: Apollo 12.

Those first four crewed trips to the Moon — Apollo 8, 10, 11 and 12 — could have all ended in potential disaster. If the Service Module had collided with the Command Module, a re-entry disaster similar to Space Shuttle Columbia could have occurred just as the USA was taking the conclusive steps of the Space Race.

View of the Apollo 11 capsule floating on the water after splashing down upon its return to Earth on... [+]July 24, 1969. If the Command Module and the Service Module had collided or interacted in any sort of substantial, unplanned-for way, the return of the first moonwalkers could have been as disastrous as the Space Shuttle Columbia"s final flight. (CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images)Getty

Atkinson"s book, Eight Years to the Moon, comes highly recommended by me if you"re interested in the behind-the-scenes details and rarely-told stories from the Apollo era. Inside, you"ll find many additional details about this event, including interview snippets with Gary Johnson himself.

Explore humanity’s first moon landing through newly discovered and restored archival footage.CNN Films “Apollo 11”premieres Sunday, June 23 at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

State media reported that the rover, which China has named Yutu-2, or Jade Rabbit-2, transmitted back the world’s first close-range image of the far side of the moon. The rover was named in a global poll in August. In Chinese foklore, Yutu is the white pet rabbit of Chang’e, the moon goddess after which the Chinese lunar mission is named, state media Xinhua reported.

The success of the mission represents a landmark in human space exploration. The area where the probe has landed faces away from Earth, meaning it is free from radio frequencies. As a result, it is not possible for a lunar rover to communicate directly with ground control. To overcome this hurdle, China launched a dedicated satellite orbiting the moon last year that will be able to relay information from the rover to Earth.

“China is on the road to become a strong space nation. And this marks one of the milestone events of building a strong space nation,” chief designer for the lunar mission, Wu Weiren, told China Central Television.

“It is highly likely that with the success of Chang’e – and the concurrent success of the human spaceflight Shenzhou program – the two programs will eventually be combined toward a Chinese human spaceflight program to the moon,” she added. “Odds of the next voice transmission from the moon being in Mandarin are high.”

Thursday’s official televised announcement that the probe had landed came approximately an hour after state media outlets China Daily and China Global Television Network deleted posts on social media proclaiming the mission a success, sparking widespread confusion as to whether the probe had made touchdown.

No explanation was given as to why the tweets were deleted. On social media, observers speculated as to the cause of the apparent backtracking, with many wondering whether the mission had experienced a temporary upset or whether it was a simple case of state media jumping the gun ahead of the official announcement.

China’s last lunar rover – named Yutu, or Jade Rabbit – ceased operation in August 2016 after 972 days of service on the moon’s surface as part of the Chang’e 3 mission. China was only the third nation to carry out a lunar landing, after the United States and Russia.

Beijing plans to launch its first Mars probe around 2020 to carry out orbital and rover exploration, followed by a mission that would include collection of surface samples from the Red Planet.

An auction house is selling memorabilia and flown artifacts from the Apollo 11 mission just in time for the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing.

The 70 mm film contains “126 of the most iconic images from thefirst lunar-landing mission,” according to a statement from the auction house, RR Auction. Some of the images were taken by astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin themselves.

The film was acquired by Terry Slezak, a member of the decontamination team at the lunar receiving lab at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center, according to the auction house. Slezak was in charge of processing the film taken on the Apollo moon landings.

Other items up for auction include Armstrong’s Robbins Medal, which on the mission with him. The medal, which was produced by NASA for each Apollo mission, sold for $45,078. Also sold was a leather log book from Air Force One that was signed by all three Apollo 11 astronauts on August 13, 1969. The log book went for $8,264.

The auction closed on Thursday evening. The moon, meanwhile, hasn’t been touched by humans since December 1972, when the astronauts with Apollo 17 left its surface.

Fifty years after NASA"s Apollo 11 mission put the first boots on the lunar surface, many plans are afoot to explore and exploit Earth"s nearest neighbor.

And China has already embarked on an ambitious robotic lunar-exploration campaign, known as Chang"e (after the Chinese moon goddess). The program successfully sent orbiters to the moon in 2007 and 2010 and dropped landers and rovers onto the surface in 2013 and January of this year. That most recent lunar mission, Chang"e 4, touched down on the moon"s mysterious far side — something that had never been done before.

The nation"s Chandrayaan-1 mission, which consisted of an orbiter and an impactor that slammed hard into the lunar surface, spotted evidence of water ice shortly after arriving at the moon in 2008. Chandrayaan-2, which successfully launched early Monday (July 22), will attempt to put a lander and rover down on the surface.

Chandrayaan-3, a possible joint effort with Japan, may send a lander and rover to a lunar pole in 2024. K. Sivan, Chairman of the India Space Research Organisation, said Monday that the country will push toward Chandrayaan-3 as it continues its push for ever-more-ambitious space missions.

Russia, which hasn"t landed on the moon since the Luna-24 mission in the mid-1970s (when the nation was still part of the Soviet Union), also plans to get in on the action soon. The country is working on Luna-25, a resource-prospecting mission to the lunar south pole that could launch in the 2022 to 2024 time frame, according to Russian space officials.

Some of this demand is already apparent. For example, Astrobotic"s Peregrine lander will carry 28 payloads on its first mission to the lunar surface, which is targeted for 2021. NASA is providing 14 of them; the other 14 will come from private companies, university groups and other organizations.

A Japanese billionaire has already booked a round-the-moon Starship mission, which is currently targeted for 2023. Blue Origin, meanwhile, is working on a big lander called Blue Moon, future iterations of which could carry people.

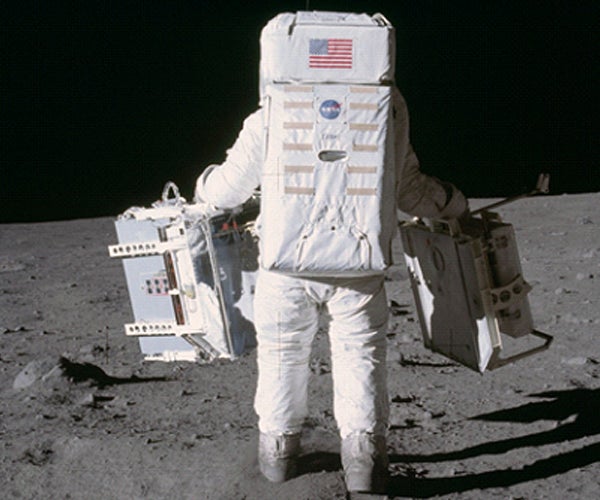

It was not so desolate when they departed. The Apollo 11 astronauts discarded gadgets, tools, and the clothesline contraption that moved boxes of lunar samples, one by one, from the surface into the module. They left behind commemorative objects—that resplendent American flag, mission patches and medals honoring fallen astronauts and cosmonauts, a coin-size silicon disk bearing goodwill messages from the world leaders of planet Earth. And they dumped things that weren’t really advertised to the public, for understandable reasons, such as defecation-collection devices. (Some scientists, curious to examine how gut microbes fare in low gravity, even proposed going back for these.)

The photographic evidence for this came decades later, thanks to NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a spacecraft that still circles the moon today. The spacecraft’s camera photographed several Apollo landing sites. The NASA astronauts who flew to the moon in the late 1960s and early 1970s always brought American flags with them. In photos of later Apollo missions, you can see, amid all the pockmarked gray terrain, a little white smudge and, right next to it, a slightly bigger, black smudge—a flag, faded from the glow of the sun, and its shadow.

The resolution of the orbiter’s cameras isn’t strong enough to make out the Apollo astronauts’ boot prints, but some may have been blasted out of existence when the exhaust of the Eagle’s engines slammed into the regolith. Subsequent Apollo missions captured footage of the turbulent experience of liftoff. “You can see a severe blowing occurring; you can see flags flapping in the wind like it’s a hurricane; you can see dust lifting off the surface everywhere,” says Phil Metzger, a planetary scientist at the University of Central Florida.

No one has ever returned to the site of Apollo 11. No one has been on the moon’s surface at all since 1972, but national governments, commercial companies, and nonprofits alike are hoping to make it. In preparation for a potential moon rush, NASA has created guidelines for future commercial spacecraft that include no-fly zones and warnings to keep a distance.

The Apollo 11 site is a historical landmark, and it should be treated as such, says Michelle Hanlon, a co-founder of For All Moonkind, an organization of lawyers who specialize in space law. Hanlon believes that the Apollo spots deserve the same protections as heritage sites on Earth. “If you go to the pyramids, you assume they’re protected,” she says. “If you think about the moon, humanity’s greatest technological achievement, you assume that’s protected, too.” Hanlon recently worked with members of Congress to write legislation that would enforce preservation rules for historic lunar sites; the Senate approved the bill this week.

If human beings someday inhabit the moon, they might consider doing more than designating the Apollo 11 landing site a landmark. They could cover the area with geodesic domes, as a protective measure against contamination, and let people come a little closer. Visitors would pop over to an Apollo 11 gift shop to browse rocket-ship keychains and chalky astronaut ice cream.

Falling back from the moon at almost seven miles a second, the crew of Apollo 11 took it in turns to broadcast their thoughts about what their mission meant. Buzz Aldrin spoke not just of it being three men on a mission to the moon, but of their flight symbolising the insatiable curiosity of mankind to explore the unknown. Mike Collins talked about the complexity of the Saturn V and the blood, sweat and tears it had taken to build. And Neil Armstrong thanked the Americans who had put their hearts and all their abilities into building the equipment and machinery that had made the journey possible.

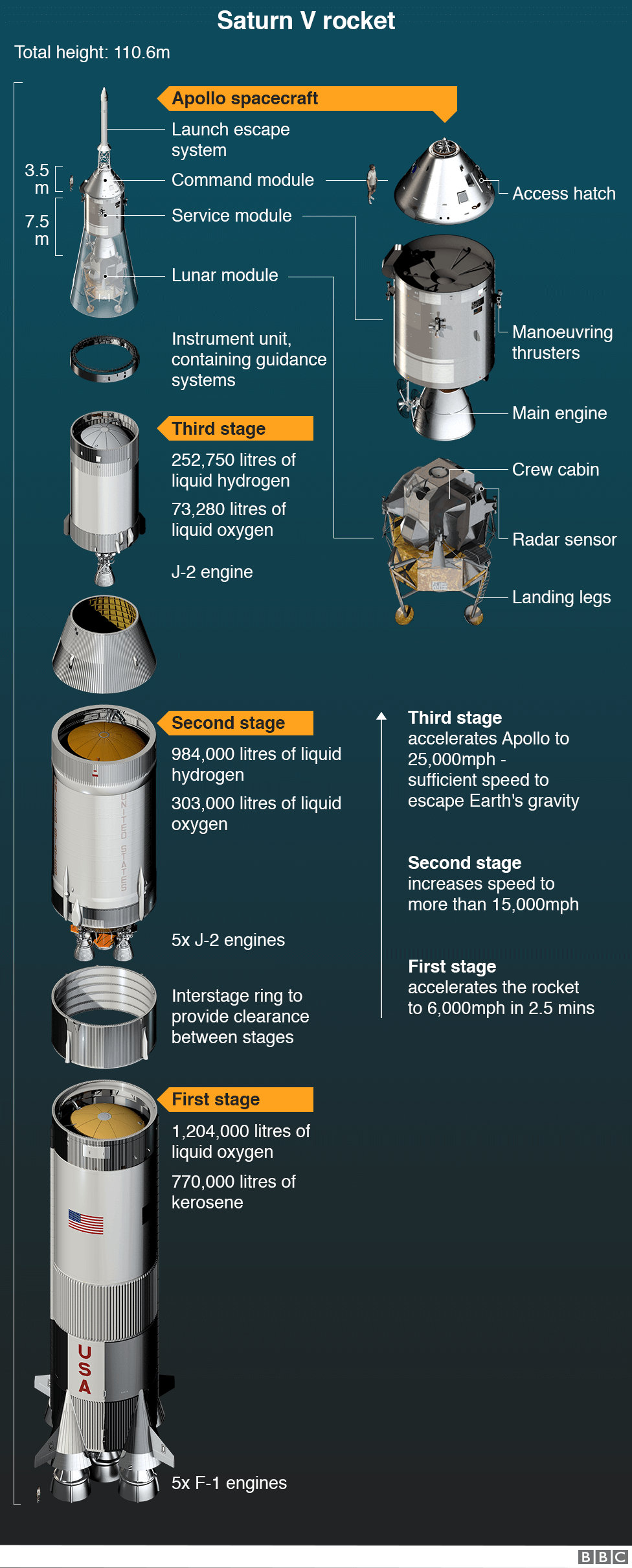

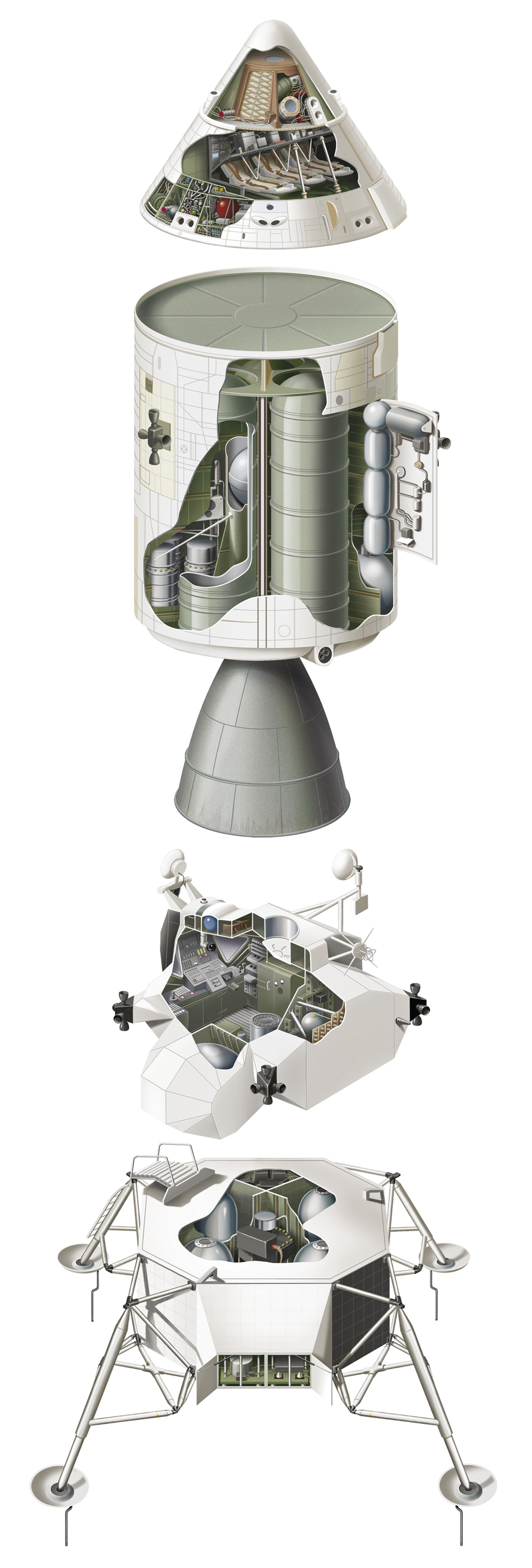

Many of these people had never worked in the aerospace industry, and none had worked before on machines designed to transport humans to another world. Overnight, as their companies won Apollo contracts, their vocations suddenly took on a greater purpose. Achieving technical miracles and overcoming bureaucratic battles, daunting setbacks and tragedies, the single "moonship" they built for the Apollo missions was effectively six individual spacecraft designed and built by five different companies. From the three separate rocket stages built by Boeing, North American Aviation and McDonnell Douglas, to the command, service and lunar modules, built by the Grumman Corporation and North American Aviation again, around five-and-a-half million parts were manufactured for each mission; often by a host of sub-contractors working for these main Apollo companies.

The near impossible task of managing this vast pyramid of people across America fell to the Apollo programme manager George Müller and, in a stroke of genius, he called upon the astronauts themselves for help; each national hero would make personal visits to the factories making all these parts. It was a crucial reminder to the workers that a single technical glitch could kill a man they had personally met. And it compelled each of them to devote their lives to Apollo for the best part of a decade.

During each flight, the colossal workforce would be on call - connected through their line managers - to a series of system support rooms in Houston which in turn fed their advice to one of 20 men in the main mission operations control room known to everyone as MOCR. Right at the top of the pyramid, inside this nerve centre, was one man in charge of each mission and his code name was Flight. For Apollo 11"s landing it was the turn of 36-year-old former fighter pilot, Gene Kranz.

An accomplishment of this immensity had transcended nationhood. Such global unity was something that no peacemaker, politician or prophet had ever quite achieved. But 400,000 engineers with a promise to keep to a president had done it and Nasa knew it. On the plaque fixed to the legs of their machine they had written the words: "We came in peace, for all mankind."Christopher Riley is the author of the new Haynes guide: Apollo 11 - an owner"s workshop manual. He curates the online Apollo film archive at Footagevault.com. His video commentaries about the Apollo mission are at theguardian.com/apollo11

The three men who took the journey became the faces of the achievement — arguably humanity’s greatest. But it was the men and women who worked in factories and offices across the nation over the better part of a decade — people like Frances “Poppy” Northcutt, the first woman in NASA’s Mission Control, and Bill Moon, a Chinese American flight controller who was the first minority to work in Mission Control — that took the moon landing from presidential challenge to tangible reality.

At the end of the Apollo 11 mission, on July 23, 1969 — 50 years ago this summer — moonwalker Neil Armstrong concluded his final television broadcast before he, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins were scheduled to return to Earth with a message to the thousands of people who had worked on the Apollo project.

“We would like to give special thanks to all those Americans who built the spacecraft; who did the construction, design, the tests, and put their hearts and all their abilities into those craft," Armstrong said. "To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all the other people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Goodnight from Apollo 11.”

At the height of the Apollo program, NASA consumed more than 4% of the federal budget, opening the way for the kind of work and testing that had to be done to achieve the moon landing. It fostered major partnerships with prime contractors including Boeing, North American Aviation (later Rockwell Standard Corp.), McDonnell Douglas, the Grumman Corporation and Rocketdyne.

And it attracted recent engineering graduates to tackle the world’s most complex problems. They were so young, in fact, that the average age of the engineers inside Mission Control when the Apollo 11 capsule splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969 was 28.

The morning of July 16, 1969, Jerry Siemers was alone in his apartment across from NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in Clear Lake, about 20 miles southeast of Houston. On the grainy TV screen before him, the Saturn V rocket he had worked on was taking off from Kennedy Space Center on a mission to the moon.

For someone who had worked on so many components of the mission, from the design of the 39A launch complex, to the rocket itself, to the lunar rover, to the Apollo spacecraft, watching the Apollo 11 mission was a equal parts ecstasy and existential dread.

“You are all tensed up waiting for something and then it all works fine and that goes on for the whole mission,” Siemers, now 79, recalled. “It was really amazing [that it succeeded.] It’s such a relief when they splashed down.”

Siemers’ work as a young mechanical engineer at Boeing spanned the Saturn V program in Huntsville, Alabama, beginning in 1964 to the Apollo (and later Apollo/Soyuz) program out of Houston through 1975. He was part of the first wave of Boeing engineers out of Huntsville to move into a converted office space at a Ramada Inn across the Manned Spacecraft Center working on systems engineering and design requirements.

At a manufacturing facility in Waltham, Massachusetts, Bob Zagrodnick was only 25 years old when he started working on the computer that would one day pilot the Apollo command and lunar modules.

The electrical engineer started out preparing the instructions to teach other engineers how the computer worked from an electrical design standpoint, before he got involved in testing the computer and doing work on prototype versions. The final version of the Apollo Guidance Computer weighed about 70 pounds and calculated position, velocity and trajectory for every Apollo mission. It was one of the first integrated circuit-based computers and a marvel at a time when technology was quickly evolving.

So quickly, in fact, that "toward the end of the program, Texas Instruments and Hewlett-Packard came out with hand-held computers that were more powerful than the [Apollo] computer,” said Zagrodnick, now 80.

But the computer and its development were instrumental in the safety and success of the lunar missions. It helped NASA circumvent the 1.5-second time delay in signal transmissions from Earth to the moon and back, allowing it to troubleshoot issues in real time, instead of relying on responses from the ground-based systems.

The Apollo Guidance Computer’s development spanned about a decade of Zagrodnick’s career. He went on to work as the engineering manager and then the program manager on Apollo for Raytheon through the end of the Apollo program and retired after 50 years at Raytheon in 2013.

During his time working on Apollo, Zagrodnick made it out to the Cape for several launches, but the memory that still sticks in his mind isn’t Apollo 11 or even a launch itself.

At launch time, DeMattia also was responsible for monitoring some of the measurements coming into the launch control center — and calling an abort if something didn’t look right. Now 72, he still keenly remembers sitting and watching a piece of paper scrolling before him with a red line across the sheet, hoping the needle measuring the data wouldn’t pass the red line indicating something was wrong and the mission had to be called off.

About two years after arriving at KSC, DeMattia went on to work with the Apollo program on the communications radios that connected the spacecraft with the team back on Earth. He stayed at the Cape until 1974, when he moved to California to design the avionics for the Space Shuttle program.

With the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission near, DeMattia is still astounded by the will that propelled the nation to accomplish the feat, one that hasn’t been repeated since the final moon landing in 1972.

This story is part of the Orlando Sentinel’s “Countdown to Apollo 11: The First Moon Landing” – 30 days of stories leading up to 50th anniversary of the historic first steps on moon on July 20, 1969. More stories, photos and videos atOrlandoSentinel.com/Apollo11.

HELSINKI — China is progressing with the development of two super heavy-lift rockets for crewed missions and infrastructure launches to the moon, according to officials.

The new crew launcher is also referred to unofficially as the CZ5DY, taking the CZ initials for the Chinese for Long March, and DY meaning “dengyue” or moon landing. The rocket is based on technology and tooling developed for theLong March 5heavy rocket variants that have launched China’s space station modules, Mars mission and a lunar sample-return.

The update on progress was provided after China marked103consecutive successful launches with its Long March rocket family, eclipsing its previous record of 102 set between 1996 and 2011.

“Space observers also pointed out that as NASA is trying hard to relive its Apollo glories, China is working on innovative plans to carry out its own crewed moon landing missions,” the article read.

8613371530291

8613371530291