apollo 11 mission parts price

An auction house is selling memorabilia and flown artifacts from the Apollo 11 mission just in time for the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing.

The 70 mm film contains “126 of the most iconic images from thefirst lunar-landing mission,” according to a statement from the auction house, RR Auction. Some of the images were taken by astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin themselves.

The film was acquired by Terry Slezak, a member of the decontamination team at the lunar receiving lab at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center, according to the auction house. Slezak was in charge of processing the film taken on the Apollo moon landings.

Other items up for auction include Armstrong’s Robbins Medal, which on the mission with him. The medal, which was produced by NASA for each Apollo mission, sold for $45,078. Also sold was a leather log book from Air Force One that was signed by all three Apollo 11 astronauts on August 13, 1969. The log book went for $8,264.

The auction closed on Thursday evening. The moon, meanwhile, hasn’t been touched by humans since December 1972, when the astronauts with Apollo 17 left its surface.

In support of the six Apollo missions that made it to the Moon between 1968 and 1972, a few auction houses have cobbled together some pretty impressive collections of lunar memorabilia. Sotheby’s has a

"It was fantastic. Obviously there is a lot of nostalgia and energy right now focused on the history of Apollo 11," said Bobby Livingston, executive vice president of RR Auction in Boston.

Livingston said the auction house received very strong prices for the Apollo 11 goods. The merchandise wasn"t limited to Apollo 11 pieces, though there were around 150 items that came from that mission specifically.

The highest bid went to a glossysigned 8-by-10 photo of Neil Armstrong just before he stepped onto the moon from NASA"s original video transmission. The final bid on the photo was $52,247.50, including the buyer"s premium. The pre-auction estimate was $12,000.

EBay has a wide selection of Apollo 11 paraphernalia, including a shard of "Genuine Gold Kapton Foil Flown to the Moon - NASA -with COA" foil for a much lesser list price than the auction items at $14.99.

Ahead of the 50th anniversary, major brands are celebrating with Apollo 11-themed merchandise, too. Krispy Kreme has launched a promotion, "One small bite for man... one giant leap for doughnut-kind," with the opportunity for customers to try one free at select locations Saturday.

Two rotational attitude control sticks and a translation hand controller from the Apollo 11 command module, Columbia, were offered by Julien"s Auctions of Beverly Hills on Saturday (July 18), 51 years after the first lunar landing mission. The artifacts were among a small collection of NASA memorabilia included in Julien"s Hollywood: Legends and Explorers sale, which also featured a nearly complete spacesuit worn in Stanley Kubrick"s 1968 film, "2001: A Space Odyssey" (the costume sold for $370,000).

"This event brings together both a fictional representation of our (then) future as well as a historic collection of some of the most important pieces used in space exploration including the actual pilot control stick used by Neil Armstrong on the Apollo 11 flight to the moon," Julien"s wrote in its introduction to the sale.

The rotation control handle that had been installed near the right hand of Apollo 11 mission commander Neil Armstrong, the first astronaut to walk on the moon, topped the three lots at $370,000 (including the buyer"s premium). A similar control stick that was positioned to the right of lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin sold for $256,000. Both were used for making adjustments to the command module"s roll, pitch, and yaw.

A T-handle translational control stick used by both Armstrong and command module pilot Michael Collins, which had been located to the left of Columbia"s left couch, sold for $156,250. The stick was used when docking the spacecraft with the lunar module Eagle after departing Earth for the moon. The same handle, when turned counterclockwise, would have also been used by Armstrong to abort the mission had the crew encountered a significant problem during their launch.

All three controllers were removed from the command module two months after it splashed down for presentation to the astronauts, but the crew reportedly refused the gifts. Instead, the handles — mounted to a custom wooden plaque with an embroidered Apollo 11 mission patch and a bright yellow NASA parts tag — were stored away in an office safe at Johnson Space Center in Houston for more than 15 years.

The National Air and Space Museum has exhibited the Apollo 11 command module since receiving it from NASA in 1971. According to the Inspector General, officials at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. pressed for the return of the hand controllers.

After 3 years, NASA ceased its pursuit of the Apollo 11 hand controllers. The OIG did not say if the agency then relinquished its title, or if in the future it might seek return of the control handles again. An inquiry to the OIG was referred to NASA"s general counsel, who was unavailable to comment in time for this article.

The hand controllers are not the only parts of the Apollo 11 command module that NASA has sought to recover after they emerged for sale. In 2000, the OIG investigated the auction of an exterior-mounted EVA (extravehicular activity, or spacewalk) handrail that was removed from Columbia post-flight due to the presence of radioactive material. The metal rail sold for $34,500 and remains in a private collection today.

Had the Apollo 11 crew accepted receipt of the hand controllers, a 2012 law would have protected their option to sell the artifacts without further NASA inquiry. The legislation, which reasserts the Apollo-era astronauts" title to the flown spacecraft hardware they retained or were presented after their missions, only applies to the crew members and not other NASA employees.

In addition to taking home the Apollo 11 control sticks, Whipkey also retained a translation control handle from the Apollo 9 spacecraft. After being contacted by the OIG, he returned that handle to NASA and it was subsequently transferred to the Smithsonian to be included in an existing display.

the astronauts, astronaut, lunar landing, moon landing, walk on the moon, apollo 11 landing, armstrong s, manned, apollo program, men on the moon, one small step for man, the eagle, saturn v, man on the moon, tranquility, sea of tranquility, splashdown, saturn v rocket, pacific ocean, walk on, mission control, earth orbit, the sea of tranquility, space center, kennedy space center, apollo 11 moon landing, saturn, land on the moon, descent, man on the moon, first man on the moon, moon landing, the first man, astronaut, the astronauts, walk on the moon, the moon landing, lunar landing, men on the moon, armstrong s, one small step for man, mission control, first moon landing, land on the moon, walk on, manned, in space, safely, sea of tranquility, space race, the eagle, the space, edwin aldrin, nixon, apollo missions, kennedy space center, space center, the sea of tranquility, kennedy, moon landing, the astronauts, the moon landing, astronaut, first moon landing, one small step for man, man on the moon, lunar landing, land on the moon, on the surface, in space, faked, apollo program, apollo missions, sea of tranquility, apollo astronauts, saturn v rocket, landing on the moon, mission control, rocket, space center, first man on the moon, hoax, manned, descent, walk on the moon, the sea of tranquility, tranquility, saturn v, american flag... space exploration, july 16, the crew, launched, exploration, president nixon, space station, the space race, first moonwalk, journey to the moon, the pacific ocean, cape kennedy, moonwalk, moon rocks, aboard, the earth, the planet earth, kennedy s, mars, earth first, two men, spacesuit, orbiter, the descent, the flag, the kennedy, lander, into space, quarantine, the ladder...

apollo program, apollo missions, lunar landing, astronaut, the astronauts, moon landing, apollo spacecraft, apollo 8, apollo 1, man on the moon, unmanned, manned, men on the moon, skylab, landing on the moon, earth orbit, lunar mission, saturn v, soyuz, orbiting, land on the moon, in space, chaffe, saturn, schmitt, 1972, apollo 18, gus grissom, lunar rover, rille...

florida institute of technology, florida institute, mission to mars, institute of technology, the red planet, astronautics, cycler, phobos, the buzz, red planet, master plan, colonizing mars, mars settlement, florida tech, occupy, pathways, colonizing, 70th anniversary, colonize mars, massachusetts institute of technology, martian, asteroid, cycling, the institute, travel voucher, the martian, colonize, rendezvous, air force, settlement...

Vintage pictures of the crew of Apollo 11 mission signed by its three Nasa astronauts,Buzz Aldrin, Michael Collins, and Neil Armstrong, the first manto walk on the Moon, are for sale. This is nowaday normal. But how much is it worth ? 3000 $ ? 7000 $ ?

The holy grail for collectors of space memorabilia is anything that was flown to the moon during the six Apollo missions and unloaded onto the celestial crust. It would be junk in any other context; vintage scientific equipment lucky enough to be projected at escape velocity to a barren destination 234,000 miles away. What makes those spare parts invaluable, explains Robert Pearlman, editor of the space-hobbyist consumer guide CollectSPACE (and an avid lunar antiquary himself), is when they’ve been stained by lunar dust — physical proof of a journey that still seems impossible.

Then you enter the Wild West of merchandise that remained on Earth — various appendages of the Apollo program, and its lesser-known progenitors Project Mercury and Project Gemini. (The value basement, says Pearlman, are the items mined out of the latter-day Skylab and Space Shuttle ventures throughout the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Space collectors, like most Americans, prefer to remember NASA when it was at its apex.)

But memorabilia from the Apollo 11 mission reigns supreme. The maiden voyage to the moon is the one most fixed in the American storybook, so it is no surprise that the trickle of mementos from that flight demand a higher price than anything that’s come before or since.

July 20th marks Apollo 11’s 50th anniversary, and Sotheby’s is celebrating on that day with a specialized auction full of material from the space program. The marquee item? Three bundles of magnetic videotape, filmed at Mission Control in Houston, Texas, which represent the “earliest, sharpest, and most accurate” documentation of the broadcasts beamed out by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as they took their first steps on the moon. The estimated market value is between $1 million and $2 million, but the original owner was a NASA intern, who bought the tapes at a government surplus auction for $217.77 in 1976. Cassandra Hatton, a senior specialist at Sotheby’s who focuses on science history, explains that the field is new enough, and volatile enough, that prices are able to jump 10,000 percent in about 40 years. This is unusual.

Space hobbyists have been around for the length of the space race, but Pearlman explains that the first formal high-society space auctions were hosted in Beverly Hills in the early ’90s by a (now-defunct) house called Superior Galleries. It was a biannual event, drawing interest from all over the country, and it gathered its merchandise by either cosigning items directly from other collectors or asking former astronauts to put their personal effects on sale. The market tends to spike whenever people are talking about space again: 1995, after the release of Apollo 13; 1999, during the 30th anniversary of Apollo 11, and so on. By 2010, major auction companies like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Bonhams were organizing their own space galas, each focused on a period of 15 years between the mid-’60s and ’70s — Earth’s brief love affair with the moon.

In the ’70s, the administration reached an agreement with the Smithsonian, effectively giving the museum the first right of refusal on all the major artifacts that NASA no longer needs. That means that Apollo’s big-ticket items — the garments that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin wore on the lunar surface, the specimens they brought back home — are in government hands, and are available for display at museums across the country.

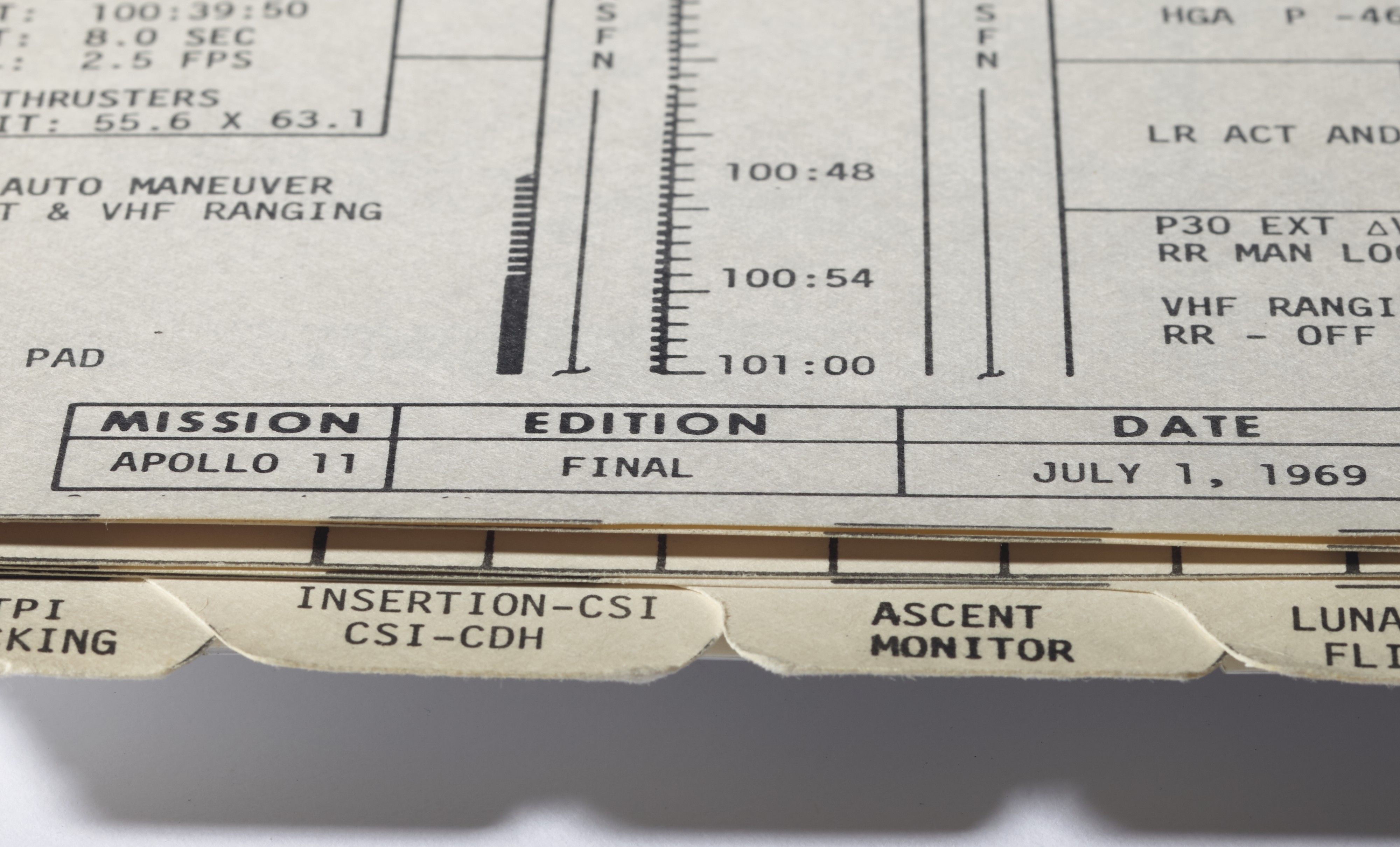

The remainder, says Pearlman, were the “nuts and bolts” of the space program — knickknacks that carry plenty of historical relevance but don’t make nearly as much sense behind a glass pane on a museum floor. (A good example is an Apollo 11 flight manual, which is expected to fetch around $9 million at a Christie’s auction this week.) A shocking number of those artifacts were plucked out of the government surplus system, just like the multimillion-dollar videotape on sale at Sotheby’s.

The other legal way Apollo material hits consumer channels is via the men who lived it. NASA outfitted astronauts with what’s called a personal preference kit, or PPK — a small bag to stow keepsakes during their missions. After they retired and returned to Earth, that material was donated, or handed down to their kids, or, as the space auction market started percolating, sold at an enormous profit margin.

These sales, in particular, did not sit well with NASA. The agency could never squabble with the material purchased legally out of surplus stores, but it did file grievance with what it saw as former employees flipping government property to make a buck. Take the case of astronaut Edgar Mitchell, who brought a camera he kept from the Apollo 14 campaign to Bonhams in 2011. The government said it had no record of transferring that camera to Mitchell’s private estate, so after a legal entanglement, Mitchell was forced to sacrifice his keepsake back to his former boss.

Naturally, “United States v. Former Astronaut Edgar Mitchell” looks pretty ugly to the average American. Mitchell had kept that camera for 40 years before attempting to cash out, and the pettiness on the municipal side looked a lot like NASA eating its own young. That controversy forced the Obama administration into action; in 2012, the president signed a bill into law guaranteeing the “full ownership rights” of most anything the crew members of the Apollo, Mercury, and Gemini missions still had in their possession — records or not. Hatton says she was thankful for the legislation, because it purged a lot of the guesswork out of space appraisal.

“The legislation specifically says not moon rocks, not spacesuits, but any other expendable items they might have kept. Checklists, and other types of hardware, that’s theirs. They’re allowed to sell it,” she says. “It’s so helpful, because I don’t have to make some sort of judgment call. ‘This flew on a mission. Okay! Did it come from an astronaut? No? Then how did you get it? You didn’t obtain this in a legal way.”

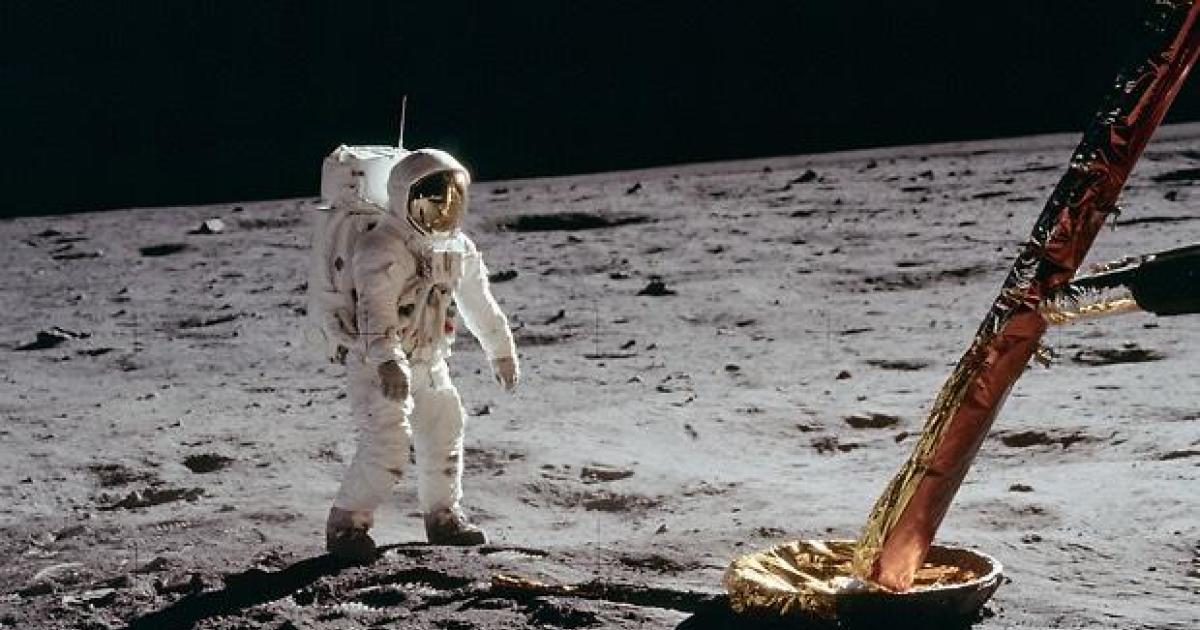

Still, a layer of tension remains when you’re bartering national treasures. The most recent, and perhaps most famous, example surfaced in 2016. A woman named Nancy Carlson bought a yellowed bag that made it to the surface of the moon during Apollo 11. It was labeled “Lunar Sample Return,” and it was previously stuffed with moon rocks that the crew scrounged up during the two hours they spent walking around the landing site.

The specifics of Carlson’s purchase are laughable; she took it home for $995 at an auction in Texas hosted by the US Marshals Service, who were selling off the forfeited artifacts of Max Ary — who was convicted for the theft and reselling of space-related items in 2006. The bag itself was worth a king’s ransom; flown to outer space on Apollo 11, handled by Neil Armstrong himself, and — yes — stained with moon dust.

It’s the sort of development that scares Michelle Hanlon, the co-founder of For All Moonkind, a nonprofit dedicated to the preservation of the lunar expeditions. She says she doesn’t have anything against private collectors, but maintains the position that anything that returned home from Apollo 11 should be classified as a public artifact — treated with tenderness and exempt from commerce. “A lot of what we’re looking for is memorialization versus preservation,” she says. “What do we need to hold in our hand forever? What do we need to make sure we don’t forget that this happened?”

Even so, the final price tag still boggles the mind. Between 1960 and 1973, NASA spent $28 billion developing the rockets, spacecraft and ground systems needed for what became the Apollo program. According to a recent analysis by the Planetary Society, that translates into an estimated $288.1 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars.

"How much was spent on Apollo, and when, is relevant as NASA has once again been directed to return humans to the moon," he writes on the Planetary Society website. "To properly evaluate the seriousness of this directive, it makes sense to compare its spending proposals to the one data point we have for a successful human lunar mission.

In reconstructing the cost of Apollo, Dreier evaluated official NASA budget submissions to Congress between 1961 and 1974, actual spending as reported by the space agency and countless supporting documents.

"The second method is to adjust the costs so that they occupy the same relative share of the nation"s economy, or Gross Domestic Product (GDP), over time," Dreier wrote. "In other words, if Apollo occupied 2 percent of GDP in 1965, what is the equivalent of 2 percent of GDP in 2019?

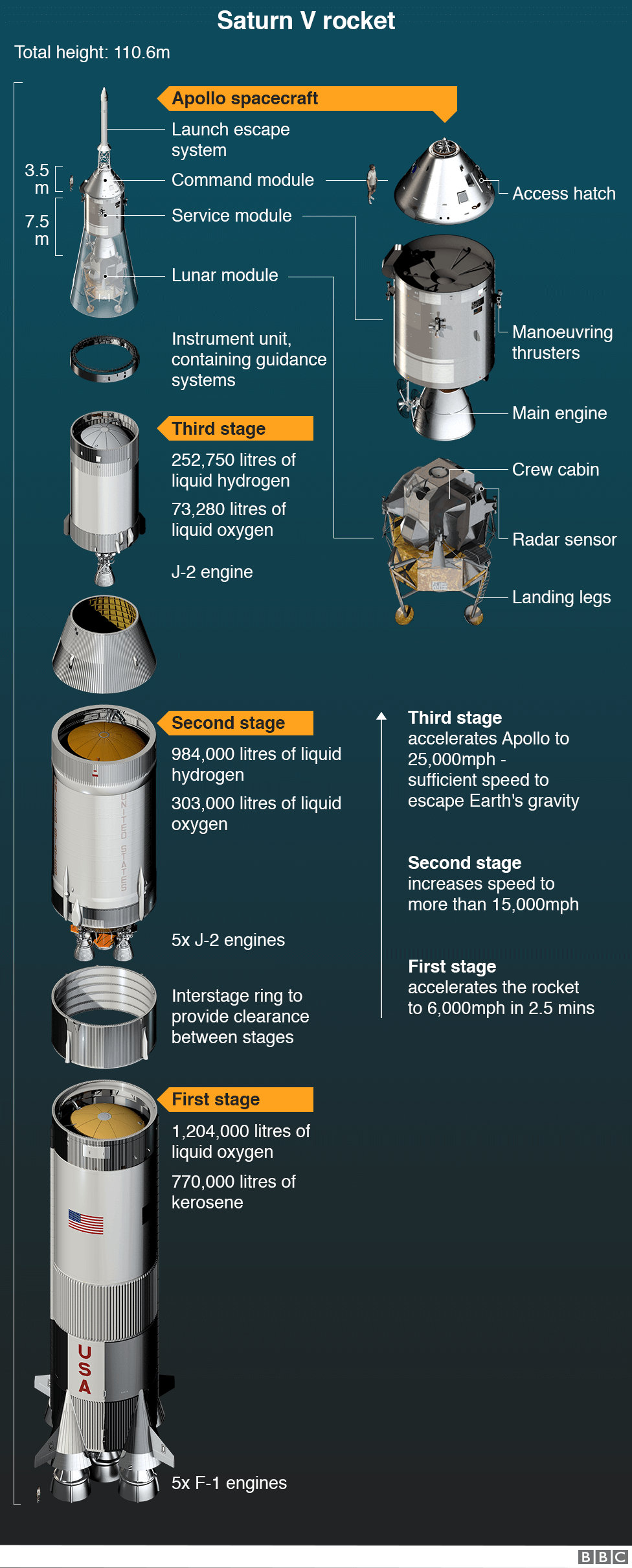

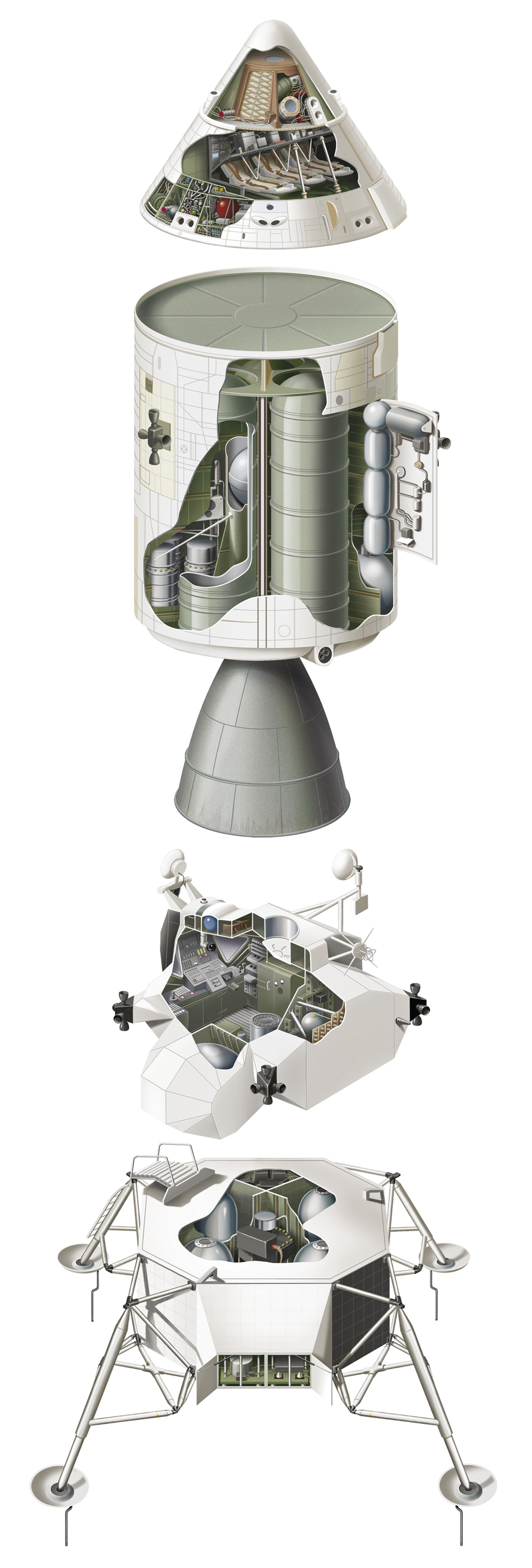

In current-year dollars, the analysis shows, the Apollo command and service modules cost the equivalent of $39 billion to develop, the lunar module ran another $23.4 billion, and the giant Saturn family of rockets and the engines required to boost astronauts into Earth orbit and beyond cost nearly $100 billion to design, test and launch.

At the peak of Apollo program spending in 1966, Dreier says, NASA accounted for roughly 4.4% of the federal budget — 6.6% of discretionary spending — more than the Manhattan Project that developed the first atomic bomb.

In terms of relative GDP, that is, the spending required in 2019 to account for the same share of the economy as the Apollo project did in the 1960s, the Planetary Society calculates the equivalent of $702.3 billion would be required.

At left: The Saturn 5 rocket that boosted the Apollo 11 mission to the moon is hauled from NASA"s Vehicle Assembly Building to the launch pad in 1969. At right: An artist"s impression of a Space Launch System rocket being prepared for a future launch to the moon.

Since 2005, NASA has spent by some estimates approximately $16 billion developing the re-purposed Orion crew capsule that will carry astronauts to and from the moon in the Artemis program and nearly $20 billion, according to at least one estimate, developing the huge Space Launch System (SLS) rocket needed to launch the lunar landing missions.

"Compared to Apollo, this is a relatively modest investment. Looking forward, we should expect significant increases in spending associated with an accelerated lunar effort or adjust our expectations accordingly."

Bill Harwood has been covering the U.S. space program full-time since 1984, first as Cape Canaveral bureau chief for United Press International and now as a consultant for CBS News. He covered 129 space shuttle missions, every interplanetary flight since Voyager 2"s flyby of Neptune and scores of commercial and military launches. Based at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Harwood is a devoted amateur astronomer and co-author of "Comm Check: The Final Flight of Shuttle Columbia."

The holy grail for collectors of space memorabilia is anything that was flown to the moon during the six Apollo missions and unloaded onto the celestial crust. It would be junk in any other context; vintage scientific equipment lucky enough to be projected at escape velocity to a barren destination 234,000 miles away. What makes those spare parts invaluable, explains Robert Pearlman, editor of the space-hobbyist consumer guide CollectSPACE (and an avid lunar antiquary himself), is when they’ve been stained by lunar dust — physical proof of a journey that still seems impossible.

Then you enter the Wild West of merchandise that remained on Earth — various appendages of the Apollo program, and its lesser-known progenitors Project Mercury and Project Gemini. (The value basement, says Pearlman, are the items mined out of the latter-day Skylab and Space Shuttle ventures throughout the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Space collectors, like most Americans, prefer to remember NASA when it was at its apex.)

But memorabilia from the Apollo 11 mission reigns supreme. The maiden voyage to the moon is the one most fixed in the American storybook, so it is no surprise that the trickle of mementos from that flight demand a higher price than anything that’s come before or since.

July 20th marks Apollo 11’s 50th anniversary, and Sotheby’s is celebrating on that day with a specialized auction full of material from the space program. The marquee item? Three bundles of magnetic videotape, filmed at Mission Control in Houston, Texas, which represent the “earliest, sharpest, and most accurate” documentation of the broadcasts beamed out by Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin as they took their first steps on the moon. The estimated market value is between $1 million and $2 million, but the original owner was a NASA intern, who bought the tapes at a government surplus auction for $217.77 in 1976. Cassandra Hatton, a senior specialist at Sotheby’s who focuses on science history, explains that the field is new enough, and volatile enough, that prices are able to jump 10,000 percent in about 40 years. This is unusual.

Space hobbyists have been around for the length of the space race, but Pearlman explains that the first formal high-society space auctions were hosted in Beverly Hills in the early ’90s by a (now-defunct) house called Superior Galleries. It was a biannual event, drawing interest from all over the country, and it gathered its merchandise by either cosigning items directly from other collectors or asking former astronauts to put their personal effects on sale. The market tends to spike whenever people are talking about space again: 1995, after the release of Apollo 13; 1999, during the 30th anniversary of Apollo 11, and so on. By 2010, major auction companies like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Bonhams were organizing their own space galas, each focused on a period of 15 years between the mid-’60s and ’70s — Earth’s brief love affair with the moon.

In the ’70s, the administration reached an agreement with the Smithsonian, effectively giving the museum the first right of refusal on all the major artifacts that NASA no longer needs. That means that Apollo’s big-ticket items — the garments that Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin wore on the lunar surface, the specimens they brought back home — are in government hands, and are available for display at museums across the country.

The remainder, says Pearlman, were the “nuts and bolts” of the space program — knickknacks that carry plenty of historical relevance but don’t make nearly as much sense behind a glass pane on a museum floor. (A good example is an Apollo 11 flight manual, which is expected to fetch around $9 million at a Christie’s auction this week.) A shocking number of those artifacts were plucked out of the government surplus system, just like the multimillion-dollar videotape on sale at Sotheby’s.

The other legal way Apollo material hits consumer channels is via the men who lived it. NASA outfitted astronauts with what’s called a personal preference kit, or PPK — a small bag to stow keepsakes during their missions. After they retired and returned to Earth, that material was donated, or handed down to their kids, or, as the space auction market started percolating, sold at an enormous profit margin.

These sales, in particular, did not sit well with NASA. The agency could never squabble with the material purchased legally out of surplus stores, but it did file grievance with what it saw as former employees flipping government property to make a buck. Take the case of astronaut Edgar Mitchell, who brought a camera he kept from the Apollo 14 campaign to Bonhams in 2011. The government said it had no record of transferring that camera to Mitchell’s private estate, so after a legal entanglement, Mitchell was forced to sacrifice his keepsake back to his former boss.

Naturally, “United States v. Former Astronaut Edgar Mitchell” looks pretty ugly to the average American. Mitchell had kept that camera for 40 years before attempting to cash out, and the pettiness on the municipal side looked a lot like NASA eating its own young. That controversy forced the Obama administration into action; in 2012, the president signed a bill into law guaranteeing the “full ownership rights” of most anything the crew members of the Apollo, Mercury, and Gemini missions still had in their possession — records or not. Hatton says she was thankful for the legislation, because it purged a lot of the guesswork out of space appraisal.

“The legislation specifically says not moon rocks, not spacesuits, but any other expendable items they might have kept. Checklists, and other types of hardware, that’s theirs. They’re allowed to sell it,” she says. “It’s so helpful, because I don’t have to make some sort of judgment call. ‘This flew on a mission. Okay! Did it come from an astronaut? No? Then how did you get it? You didn’t obtain this in a legal way.”

Still, a layer of tension remains when you’re bartering national treasures. The most recent, and perhaps most famous, example surfaced in 2016. A woman named Nancy Carlson bought a yellowed bag that made it to the surface of the moon during Apollo 11. It was labeled “Lunar Sample Return,” and it was previously stuffed with moon rocks that the crew scrounged up during the two hours they spent walking around the landing site.

The specifics of Carlson’s purchase are laughable; she took it home for $995 at an auction in Texas hosted by the US Marshals Service, who were selling off the forfeited artifacts of Max Ary — who was convicted for the theft and reselling of space-related items in 2006. The bag itself was worth a king’s ransom; flown to outer space on Apollo 11, handled by Neil Armstrong himself, and — yes — stained with moon dust.

It’s the sort of development that scares Michelle Hanlon, the co-founder of For All Moonkind, a nonprofit dedicated to the preservation of the lunar expeditions. She says she doesn’t have anything against private collectors, but maintains the position that anything that returned home from Apollo 11 should be classified as a public artifact — treated with tenderness and exempt from commerce. “A lot of what we’re looking for is memorialization versus preservation,” she says. “What do we need to hold in our hand forever? What do we need to make sure we don’t forget that this happened?”

Even so, the final price tag still boggles the mind. Between 1960 and 1973, NASA spent $28 billion developing the rockets, spacecraft and ground systems needed for what became the Apollo program. According to a recent analysis by the Planetary Society, that translates into an estimated $288.1 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars.

"How much was spent on Apollo, and when, is relevant as NASA has once again been directed to return humans to the moon," he writes on the Planetary Society website. "To properly evaluate the seriousness of this directive, it makes sense to compare its spending proposals to the one data point we have for a successful human lunar mission.

In reconstructing the cost of Apollo, Dreier evaluated official NASA budget submissions to Congress between 1961 and 1974, actual spending as reported by the space agency and countless supporting documents.

"The second method is to adjust the costs so that they occupy the same relative share of the nation"s economy, or Gross Domestic Product (GDP), over time," Dreier wrote. "In other words, if Apollo occupied 2 percent of GDP in 1965, what is the equivalent of 2 percent of GDP in 2019?

In current-year dollars, the analysis shows, the Apollo command and service modules cost the equivalent of $39 billion to develop, the lunar module ran another $23.4 billion, and the giant Saturn family of rockets and the engines required to boost astronauts into Earth orbit and beyond cost nearly $100 billion to design, test and launch.

At the peak of Apollo program spending in 1966, Dreier says, NASA accounted for roughly 4.4% of the federal budget — 6.6% of discretionary spending — more than the Manhattan Project that developed the first atomic bomb.

In terms of relative GDP, that is, the spending required in 2019 to account for the same share of the economy as the Apollo project did in the 1960s, the Planetary Society calculates the equivalent of $702.3 billion would be required.

At left: The Saturn 5 rocket that boosted the Apollo 11 mission to the moon is hauled from NASA"s Vehicle Assembly Building to the launch pad in 1969. At right: An artist"s impression of a Space Launch System rocket being prepared for a future launch to the moon.

Since 2005, NASA has spent by some estimates approximately $16 billion developing the re-purposed Orion crew capsule that will carry astronauts to and from the moon in the Artemis program and nearly $20 billion, according to at least one estimate, developing the huge Space Launch System (SLS) rocket needed to launch the lunar landing missions.

"Compared to Apollo, this is a relatively modest investment. Looking forward, we should expect significant increases in spending associated with an accelerated lunar effort or adjust our expectations accordingly."

Bill Harwood has been covering the U.S. space program full-time since 1984, first as Cape Canaveral bureau chief for United Press International and now as a consultant for CBS News. He covered 129 space shuttle missions, every interplanetary flight since Voyager 2"s flyby of Neptune and scores of commercial and military launches. Based at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Harwood is a devoted amateur astronomer and co-author of "Comm Check: The Final Flight of Shuttle Columbia."

Apollo 11 was a critical step forward for the nascent manned space flight program in America, a repurposing of nuclear weapons technology and a show of geopolitical dominance, a program rooted in the ineffable “right stuff” of the seemingly fearless naval test pilots who served as guinea pigs for the first flights into space.

In years to come, the first women and people of color to become NASA astronauts would be launched into space, the idea of private commercial space travel would become increasingly real, and one more step in the journey of Apollo 11 would be taken, again from the Pacific Northwest.

Blue Origin, one of a small number of private space-travel efforts, is the work of Amazon CEO and Seattle-area resident Jeff Bezos. Along with Elon Musk’s SpaceX, Blue Origin received no shortage of publicity since its founding in 2001. What has received less publicity is Bezos’ involvement with the artifacts left behind by Apollo 11, and the powerful Saturn V rockets that launched Armstrong, Aldrin, Collins and the astronauts who followed them into space.

Like Dr. James Joki’s backpacks and part of the lunar module, all abandoned on the moon during the journey of Apollo 11, the F-1 rocket engines that launched the spacecraft for NASA’s Apollo program were also dropped en route. They crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, where they fell 14,000 feet below the surface. They’d stay there for over 40 years.

But in 2010, Bezos, who has recounted watching the moon landing with wonder as a boy, quietly funded a recovery mission, and two expeditions led by David Concannon, a deep-water search and recovery expert, whose teams included a number of Seattleites. With limited geographic information provided by NASA about where the pieces might have ended up, the groups set to work, and ultimately retrieved several elements related to the F-1 rocket engines used at launch for Apollo 11, 12 and 16. The haul included the center F-1 engine from Apollo 11.

The remains of all three F-1s are now on display at the Museum of Flight in Seattle, and include an injector plate from Apollo 12, where, Huetter explains, the final combustion for liftoff would have entered the engine.

The three men who took the journey became the faces of the achievement — arguably humanity’s greatest. But it was the men and women who worked in factories and offices across the nation over the better part of a decade — people like Frances “Poppy” Northcutt, the first woman in NASA’s Mission Control, and Bill Moon, a Chinese American flight controller who was the first minority to work in Mission Control — that took the moon landing from presidential challenge to tangible reality.

At the end of the Apollo 11 mission, on July 23, 1969 — 50 years ago this summer — moonwalker Neil Armstrong concluded his final television broadcast before he, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins were scheduled to return to Earth with a message to the thousands of people who had worked on the Apollo project.

“We would like to give special thanks to all those Americans who built the spacecraft; who did the construction, design, the tests, and put their hearts and all their abilities into those craft," Armstrong said. "To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all the other people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Goodnight from Apollo 11.”

At the height of the Apollo program, NASA consumed more than 4% of the federal budget, opening the way for the kind of work and testing that had to be done to achieve the moon landing. It fostered major partnerships with prime contractors including Boeing, North American Aviation (later Rockwell Standard Corp.), McDonnell Douglas, the Grumman Corporation and Rocketdyne.

And it attracted recent engineering graduates to tackle the world’s most complex problems. They were so young, in fact, that the average age of the engineers inside Mission Control when the Apollo 11 capsule splashed down in the Pacific Ocean on July 24, 1969 was 28.

The morning of July 16, 1969, Jerry Siemers was alone in his apartment across from NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in Clear Lake, about 20 miles southeast of Houston. On the grainy TV screen before him, the Saturn V rocket he had worked on was taking off from Kennedy Space Center on a mission to the moon.

For someone who had worked on so many components of the mission, from the design of the 39A launch complex, to the rocket itself, to the lunar rover, to the Apollo spacecraft, watching the Apollo 11 mission was a equal parts ecstasy and existential dread.

“You are all tensed up waiting for something and then it all works fine and that goes on for the whole mission,” Siemers, now 79, recalled. “It was really amazing [that it succeeded.] It’s such a relief when they splashed down.”

Siemers’ work as a young mechanical engineer at Boeing spanned the Saturn V program in Huntsville, Alabama, beginning in 1964 to the Apollo (and later Apollo/Soyuz) program out of Houston through 1975. He was part of the first wave of Boeing engineers out of Huntsville to move into a converted office space at a Ramada Inn across the Manned Spacecraft Center working on systems engineering and design requirements.

At a manufacturing facility in Waltham, Massachusetts, Bob Zagrodnick was only 25 years old when he started working on the computer that would one day pilot the Apollo command and lunar modules.

The electrical engineer started out preparing the instructions to teach other engineers how the computer worked from an electrical design standpoint, before he got involved in testing the computer and doing work on prototype versions. The final version of the Apollo Guidance Computer weighed about 70 pounds and calculated position, velocity and trajectory for every Apollo mission. It was one of the first integrated circuit-based computers and a marvel at a time when technology was quickly evolving.

So quickly, in fact, that "toward the end of the program, Texas Instruments and Hewlett-Packard came out with hand-held computers that were more powerful than the [Apollo] computer,” said Zagrodnick, now 80.

But the computer and its development were instrumental in the safety and success of the lunar missions. It helped NASA circumvent the 1.5-second time delay in signal transmissions from Earth to the moon and back, allowing it to troubleshoot issues in real time, instead of relying on responses from the ground-based systems.

The Apollo Guidance Computer’s development spanned about a decade of Zagrodnick’s career. He went on to work as the engineering manager and then the program manager on Apollo for Raytheon through the end of the Apollo program and retired after 50 years at Raytheon in 2013.

During his time working on Apollo, Zagrodnick made it out to the Cape for several launches, but the memory that still sticks in his mind isn’t Apollo 11 or even a launch itself.

At launch time, DeMattia also was responsible for monitoring some of the measurements coming into the launch control center — and calling an abort if something didn’t look right. Now 72, he still keenly remembers sitting and watching a piece of paper scrolling before him with a red line across the sheet, hoping the needle measuring the data wouldn’t pass the red line indicating something was wrong and the mission had to be called off.

About two years after arriving at KSC, DeMattia went on to work with the Apollo program on the communications radios that connected the spacecraft with the team back on Earth. He stayed at the Cape until 1974, when he moved to California to design the avionics for the Space Shuttle program.

With the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission near, DeMattia is still astounded by the will that propelled the nation to accomplish the feat, one that hasn’t been repeated since the final moon landing in 1972.

This story is part of the Orlando Sentinel’s “Countdown to Apollo 11: The First Moon Landing” – 30 days of stories leading up to 50th anniversary of the historic first steps on moon on July 20, 1969. More stories, photos and videos atOrlandoSentinel.com/Apollo11.

This statistic shows the estimated cost of each individual Apollo mission, from Apollo 7 in 1968 to the final mission, Apollo 17, in 1970. Apollo 7 received less than fifty percent of all other missions, receiving just 145 million dollars compared to all others which received between 300 and 450 million dollars. Apollo 11, the first mission to successfully land man on the moon, cost approximately 355 million dollars, and the final mission, Apollo 17, cost approximately 450 million dollars. After the Apollo 13 incident, the amount of money invested in each mission jumped from 375 million for Apollo 13, to 400 and 445 million for Apollo 14 and 15; this was because of the increased investment in safety procedures and mechanisms to prevent further accidents from taking place.Read moreExpenditure of NASA"s Apollo Missions from 1968 to1972(million of US dollars)tablecolumn chartMissionMillions of US dollarsApollo 17450

The Planetary Society. (July 16, 2019). Expenditure of NASA"s Apollo Missions from 1968 to1972 (million of US dollars) [Graph]. In Statista. Retrieved March 03, 2023, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/1028322/total-cost-apollo-missions/

The Planetary Society. "Expenditure of NASA"s Apollo Missions from 1968 to1972 (million of US dollars)." Chart. July 16, 2019. Statista. Accessed March 03, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1028322/total-cost-apollo-missions/

The Planetary Society. (2019). Expenditure of NASA"s Apollo Missions from 1968 to1972 (million of US dollars). Statista. Statista Inc.. Accessed: March 03, 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1028322/total-cost-apollo-missions/

The Planetary Society. "Expenditure of Nasa"s Apollo Missions from 1968 To1972 (Million of Us Dollars)." Statista, Statista Inc., 16 Jul 2019, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1028322/total-cost-apollo-missions/

The Planetary Society, Expenditure of NASA"s Apollo Missions from 1968 to1972 (million of US dollars) Statista, https://www.statista.com/statistics/1028322/total-cost-apollo-missions/ (last visited March 03, 2023)

Expenditure of NASA"s Apollo Missions from 1968 to1972 (million of US dollars) [Graph], The Planetary Society, July 16, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1028322/total-cost-apollo-missions/

8613371530291

8613371530291