rat king mission parts made in china

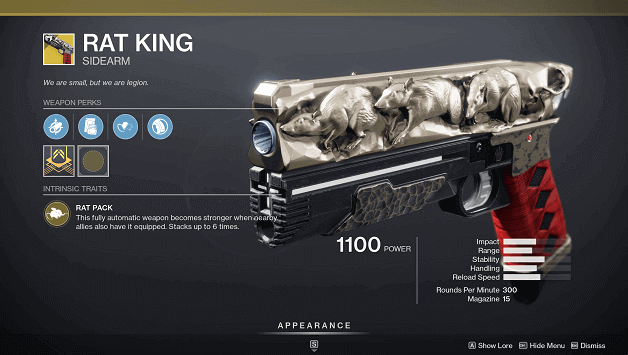

Similar to many of Destiny 2"s Exotics, the Rat King requires you to complete a special quest, involving several steps - some of which hidden behind some pretty obscure riddles.

It"s worth it though, as the Rat King has some pretty awesome perks: an increase in damage, which stacks up to six times, depending on the number of other allies that have the weapon equipped nearby; and a second or two of invisibility, granted every time you reload immediately after getting a kill with the weapon.

Complete the quest Enemy of my Enemy - it"s a blue quest marker you"ll find in the world and on your map, which ends in you being given the option to kill or save an enemy captain. Either way, when you complete it, you"ll get the Rat King"s Crew item. The item takes up a Kinetic Weapon slot, but can"t be used as one.

On the Rat King"s Crew you"ll find a strange riddle. This is, in fact, the first of four riddles, and you"ll need to solve them, and then complete their respective tasks, one at a time to get the weapon itself. Read on for detailed solutions to these in the section below!

The main sticking point comes from figuring out what the four Rat King riddle solutions are, and then there"s the matter of actually completing the final one, which is most definitely not easy. Here"s a handy video from YouTuber KackisHD, with our full written description of how to do it, in detail, below!

Pack a PunchTo access pack a punch, you"ll need to collect three items: a pink cat flyer, a token, and a film reel. The flyer and reel have multiple locations while the token only has one. Once all 3 parts have been collected, take the parts and use them to get into the private room in the Pink Cat Club outside the Disco Inferno.

Down there, you"ll see electricity sparking from the tracks. Get on the tracks and interact with the electricity to place the fuses (I typically do it on the side closest to Bang Bangs). Watch out for the Train!

Rat CagesOnce you"ve gotten the Shurikens, speak to Pam Grier and it will spawn Rat cages around the map. You can start at any rat cage location by throwing the shuriken at the rat cage, releasing the rat. I prefer starting at the one up the ramp across from the Dojo.

You"ll need to follow this rat as it goes into other rat cages around the map. Once the rat enters a new cage, Throw a Shuriken at the cage to release it again. Once you"ve done enough cages, the final cage will spawn a Large yellow circle.

First Rat King FightGo and find the Rat King icon directly outside the Dojo and interact with it. It will spawn the first Rat King. He"s just a damage sponge, so shoot him till he drops back into the ground. He will drop an eye on death. Take the eye.

After talking to Pam, you"ll need to find 6 orange Rat King symbols around the map. Pressing your tactical grenade button will activate the eye and activate a temporary vision that will allow you to see the symbols in the map.

After determining the number from the phone, these numbers will correspond to a Nightmare Summer Poster in the map. You need to collect the poster that has YOUR number on it. There are 6 locations for the posters. PAY ATTENTION TO THE NUMBER IN THE BOTTOM LEFT. Trying to collect the wrong poster will result in you having to collect the rat king symbols again.

Start by looking at what letter you have on the wall. That alone should weed out majority of the words. Then look at the second letters for those words and see which of those letters appear as symbols on the rooftop. Keep doing this method of elimination and this step shouldn"t be too much of a hassle.

Second Rat King FightMove to the rooftops up the stairs from Racin" Stripes and you"ll find another Rat King boss fight symbol. Interact with it and kill him, just like the first time. This time he"ll drop his Brain. Pick the Brain up and SPEAK WITH PAM

After speaking with Pam, you"ll notice a burn mark in the Top left of the screen flashing. This signifies that after 3 rounds, the film will break and will progress you 3 rounds. Simply just use this time to get some setup done.

Soul CollectingAfter replacing the turnstyle, make your way to the alley by Mule Munchies and climb the scaffolding. Up there, in the one of the windows, you"ll see a Rat king symbol, shoot it and the window will close and spawn a golden soul collection ring

The goal with this is to kill the zombie with the Disco ball above its head only when another zombie is on the checkered floor. Do this enough times until you hear the gong sound and you can move the to the last Rat king fight before the main boss fight.

Third Rat King FightJust the same as the other two fights, make your way outside the Disco inferno and in front of the Pink cat and you"ll find another Rat King symbol. Interact with it, kill the Rat King and this time he"ll drop his heart which can be used as a lethal equipment.

The damage phase is pretty self-explanatory. Damage the Rat King until he sinks into the ground and spawns the items for you to pick up, or if you"re on the final stage, until he dies.

How to start a phaseThe three items we"ve collected (the eye, brain and heart) throughout the quest will appear around the boss fight arena. Simply collect one of the items and place it in the middle of the arena on the big Rat King symbol that will spawn and the phase will begin. Again, you can do these in any order you chose.

The goal of this phase to have the blue eyed zombies attack the brain. Using the Shurikens on the Rat King"s staff when he goes to kill the zombies can make the phase go by quicker, but it"s not necessary.

This step isn"t too difficult. You simply just need to keep activating the eye to enter the Rat Vision and shoot the symbols in the room. The Rat King will throw more symbols out into the room, so you"re goal is to clear them all before he has time to throw more out.

Final Damage PhaseOnce all the main phases have been completed, you"ll be in the final damage phase. Unload into the Rat King till he dies and the cutscene plays! Once the cutscene ends, pick up the soul key and you are done!

I am at my end for patience, this mission is killing this game for me. I"ve tried looking up guides and everything for it and yet I still get killed at the start, as if suddenly all the guides are null and void. Didn"t complete the Rafnir mission if it matters, and why would it as i"ll have to come back to this if i want to advance. I feel this is such terrible game design as your not even given a chance to get a building up before all the peasant killers show up. Am I the only one stuck on this mission?

I"ve long since beaten Majesty 2 and its expansions so if any came here for help here"s the breakdown. Rat King and Fafnir are your skillgate missions with Rat King punishing you for the mentality of building around your castle and forcing you to build away from it (about a Market and halfs worth), be it South East or South West. Slam down Ranger"s Guild, Market+Health Potions, and a Tower to help collect taxes from your isolated buildings. From there Cleric and Warrior guilds to keep your heroes alive and give you bit of a sturdier frontline. With your tax collectors safe and economy going you can move to stabilize the area around your castle with towers. Start with one corner and only build one at a time, and expand with a blacksmith as you go. Once the towers are up you"ve stabilized and can then proceed as normal with expansion till you win.

King Rat is festering with atmosphere and drowns you in a cacophony of Jungle Bass and Drum. It takes you to London’s underside, it’s stinking bowels, and gives life to the world below. It does all this in a very good way. I swear. King Rat is my first taste of Mieville and I’m still not sure if it was the best place for me to start, but it certainly isn’t a bad place to start. This is his debut novel and does not seem to be as widely read or recommended. I have also heard that it is a bit different from the rest of his novels. Since I obviously have not read the others, I can’t comment on that myself. But I can share what I thought of King Rat.

I also found the accent/dialogue from one of the characters (Anansi) a bit grating and kind of hard to read. I think if I was familiar with the accent he was trying to get across, it would have flowed much better, but since I wasn’t it just read very awkward. Luckily, he did not have much to say. And sometimes, it was short, and I didn’t have a problem. But if he had a paragraph worth of dialogue, chances are, I had to slow down my reading, and would get pulled out a bit to wonder what he was really supposed to sound like versus my awkward attempt at it. But, minor complaint. Really.

Introduced in infected anomaly, dubbed the rat king, is a super-organism composed of multiple stalkers, clickers, and a bloater that have been connected together by the Cordyceps fungus.

The rat king possesses incredible strength and resilience, surpassing that of a bloater, shown in how it could easily smash through and destroy much of the lower levels of the hospital, including an ambulance, and was capable of taking extensive damage before dying.

After taking enough damage, some of the intertwined infected can break off from the larger mass. Once an infected has detached, it can have traits shared with other types of infected. For instance, one infected which detached resembled a stalker in behavior and appearance but was able to throw sacks of mycotoxin similar to bloaters. It appears every single infected connected to the mass are their own entity as opposed to the mass being a single one.

Given Nora"s comments, it appears the rat king is made up of some of the first people ever be infected by Cordyceps brain infection in the city of Seattle, meaning it developed into this state after 25 years of infection. It appears to have formed by being sealed in a room so full of spores that as the fungal growths bloomed and spread, the infected were merged into each other. The rat king found in the basement of the Seattle hospital is the only known case of conjoined infected.

The rat king is the strongest known infected and as such can take gargantuan amounts of damage. It is advised the player save bombs, flamethrower ammunition and craft incendiary rounds in order to deal massive damage to this infected quickly. The player should also run often and keep their distance because the rat king can charge through all types of attacks, even fire assaults. If the player does not escape, the rat king will kill Abby either by corroding her skin with mycotoxin, emitting it like how shamblers do, or grabbing her to snap her neck and violently rip off her limbs.

After the first phase of the fight, the rat king will split into two parts: a bloater and stalker part. This is the second phase. As the stalker is invincible until the bloater half is killed, the player should focus on luring the bloater half into the supply room in the back left corner of the basement to funnel it into the corridor and resupply on ammunition in the area.

According to co-directors Anthony Newman and Kurt Margenau, the rat king"s appearance took inspiration from the films Zygote and Annihilation, as well as the video game Inside. Additionally, its battle took inspiration from the boss fights of Magni and Modi from God of War and Elieen the Crow from Bloodborne. A note hinting that there were more rat kings elsewhere, as well as a line from Abby that explicitly names the creature ("Fuck this... Rat... King?!") were cut from the game.

As the rat king, the stunt performers were tied to each other while performing mocap with Kelli Barksdale stacked on top of Jesse La Flair and Walter Gray IV.

The rat king is based on a real life phenomenon, where numerous rats are found constrained together because their tails intertwine or are bound together. Like the sole "rat king" infected seen in the game, real-life rat kings are rarely seen.

The most important task for any Destiny player is raising their Power level, which is the combined level of equipped weapons and armour. There’s a sense of unspoken competition to get the rarest and finest-looking gear, with many devoting all of their time to looking the best.

The original Destiny included exotic weapons and armour that could only be obtained by fulfilling certain objectives, known to be difficult and almost impossible to complete.Destiny 2is no different and many players have already unearthed the first one – a sidearm weapon known as Rat King. Obtaining the coveted gun isn’t easy but if you’re interested in picking it up and becoming the envy of your friends, here’s how to do it.

Once you’ve beaten all of the story missions and reached the maximum level of 20, the "Enemy of the Enemy" side quest will appear on the planet Titan. Upon completion, you’ll be rewarded with the "Rat King’s Crew" item which takes up a space in your Kinetic weapon slot, although it isn’t a useable weapon just yet.

Once you view the Rat King’s Crew item in your inventory, a set of four riddles will appear, which you’ll need to solve whilst paired up with at least one other player in a Fireteam. Once all four riddles have been solved, Rat King’s Crew will morph into the coveted exotic sidearm weapon.

Riddle 1: “The Rat King’s Crew / Runs to and fro / Good girls and boys / Know where to go / Pick up your toys and darn your socks / on errands of woe, on errands we walk”

In order to solve the first of the four mind-boggling Rat King riddles, simply complete three patrols with your Fireteam. If you haven’t unlocked the ability to do them yet, travel to the European Dead Zone and complete the mission "Patrol" to gain access. Once unlocked, you can pick up patrols from flashing green beacons scattered throughout the many planets.

Riddle 2: “The Rat Kind’s Crew / Goes Arm in arm / To fight as one / To do no harm / So have your fun and run outside / Rally the flag and we’ll never die”

Riddle 3: “The Rat King’s Crew / Goes four and four / With good good fights / They learn to score /Then three as one they stand upright / Return from past the wall and wanting more”

Riddle 4: “The Rat King’s Crew / Stands three as one / They see Night’s fall / And fear it none / But watch the clock as you scale the wall / Lest five remain hope comes for none”

Riddle number four cranks up the difficulty notch and is by far the most frustrating part to solve. This time, you and your Fireteam need to successfully beat the weekly Nightfall strike with at least five minutes left on the clock. If you’ve yet to unlock Nightfalls, complete two normal strikes in the strike playlist and then level up your Power level to 240. Beating the weekly Nightfall strike is a challenge in itself so having to complete it with at least five minutes remaining is no easy task but we believe in you, Guardian.

A rat king is a collection of rats whose tails are intertwined and bound together in some way. This may be a result of an entangling material like hair, a sticky substance such as sap or gum, or the tails being tied together. Historically, this phenomenon is particularly associated with Germany.

The original German term, Rattenkönig, was calqued into English as rat king, and into French as roi des rats. The term was not originally used in reference to actual rats, but for persons who lived off others. Conrad Gesner in Historia animalium (1551–58) stated: "Some would have it that the rat waxes mighty in its old age and is fed by its young: this is called the rat king." Martin Luther stated: "finally, there is the Pope, the king of rats right at the top." Later, the term referred to a king sitting on a throne of knotted tails.

An alternative theory states that the name in French was rouet de rats (or a spinning wheel of rats, the knotted tails being wheel spokes), with the term transforming over time into roi des rats,oi was pronounced

Specimens of purported rat kings are kept in some museums. The museum Mauritianum in Altenburg, Thuringia, shows the largest well-known mummified "rat king", which was found in 1828 in a miller"s fireplace at Buchheim. It consists of 32 rats.Hamburg, Göttingen, Hamelin, Stuttgart, Strasbourg and Nantes.

A rat king found in 1930 in New Zealand, displayed in the Otago Museum in Dunedin, was composed of immature black rats whose tails were entangled by horse hair.

A rat king discovered in 1963 by a farmer at Rucphen, Netherlands, as published by cryptozoologist M. Schneider, consists of seven rats. All of them were killed by the time they were examined.callus at the fractures of their tails, which suggests that the animals survived for an extended period of time with their tails tangled.

Sightings of the phenomenon in modern times, especially where the specimens are alive, are very rare. One 2005 sighting comes from an Estonian farmer in Saru, of the Võrumaa region;University of Tartu Museum of Zoology in Estonia, were alive. In 2021, a living "rat king" of five mice was caught on video (and untangled to save the mice) near Stavropol, Russia.

On October 20, 2021, a live rat king of 13 rats was found in Põlvamaa, Estonia. The rat king was brought to Tartu University and humanely euthanized because the rats had no way of freeing themselves. Before that, scientists were able to film the rat king alive. The rat king will be added to the Tartu University Museum of Zoology collection.

Instances of squirrel kings have been reported. They were found alive in some cases, and veterinarians have had to separate them as the squirrels could potentially starve or be eaten by a predator.Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada in June 2013.Wisconsin, US. Some surrounding nest material, grass, and plastic got further entangled with them.

Rat kings have been reported from Germany, Belgium, Estonia, Java, and New Zealand, with the majority of cases reported from the European countries. The existence of this phenomenon is debated due to the limited evidence of it occurring naturally, although the finding of a live one in Estonia in 2021 is considered to be proof that it is a natural, albeit extremely rare phenomenon.naturalists proposed many hypotheses to explain this phenomenon. Most were dubious, ranging from the rats getting stuck together during birth and glued later, to healthy rats deliberately knotting themselves to weaker rats to make a nest. A possible explanation is that the long flexible tail of the black rat could be exposed to sticky or frozen substances such as sebum (a secretion from the skin itself), sap, food, or excretory products. This mixture acts as a bonding agent and may solidify as rats sleep especially when the animals live in proximity during winter. After realizing that they were bound, they would struggle, tightening the knot. This explanation is plausible given that most cases have been found during winter and in confined spaces.

Some zoologists remain skeptical, saying that, while theoretically possible, the rats would not be able to survive in such a condition for a long time,rodent family.Proceedings of the Estonian Academy of Science, Biology, and Ecology, following the finding of the University of Tartu specimen, concluded that the phenomenon is possible but rare.

Rat kings appear in novels such as Stephen King, Annie Proulx, Bryan Talbot, Michael Dibdin, Daniel Kraus, Scott Westerfeld, Chris Wooding, Rats and Gargoyles by Mary Gentle, Neil Cross, The War for the Lot by Sterling E. Lanier, Cold Storage by David Koepp, where it plays a prominent role, and The Rats by James Herbert. The Lorrie Moore short story Wings features a couple who discover a rat king in their attic. In Alan Moore and Ian Gibson"s comic book series

In Terry Pratchett, Keith skeptically notes that the filth associated with supposedly tying the young rats together at a young age is not found in a rat"s nest, and suspects that a rat king is created as a sort of project by a rat catcher himself. One rat king, called Spider due to having eight component rats, supports this by his grudge against humanity for his traumatic creation. In an author"s note at the end of the novel, Pratchett ventures the theory that "down the ages, some cruel and inventive people have had altogether too much time on their hands".

E. T. A. Hoffmann"s Mausekönig) with seven heads, seemingly inspired by the multiple-bodied rat king. The character is typically depicted as multi-headed in productions of the Tchaikovsky ballet

In the eleventh episode of the sixth season of Teen Wolf, "Said the Spider to the Fly", Liam Dunbar and Mason Hewitt encounter a rat king. The sixth episode of the first season of Jack Meets Dennis", Dennis Duffy claims to have seen a rat king. Later, Liz Lemon describes what her future with Dennis would be like, becoming "more and more tangled up in each other"s lives until [she] can"t even get away," and realizes that he is a metaphorical rat king. An episode of the NBC TV urban fantasy series Portland, formed by multiple "Rienegen" (were-rats) conjoining their body mass. An episode of the Netflix TV show

The phenomenon"s name appeared as the title of a Boston Manor song released in 2020. When asked about it, vocalist Henry Cox explained that he used the rat king as a metaphor for current political and social events.

A creature known as the Rat King is featured in the 2020 action-adventure video game Abby explores the underground levels of a hospital in Seattle which were ground zero for the outbreak in the city over 20 years before.motion capture for the creature.

In 2006 the Chinese government began massive efforts to clean up Beijing before the Olympics by implementing emission controls and traffic restrictions. Zhang realized he could use the city as a laboratory to see if the efforts would work and to what extent.

Zhang and graduate student Xing Wang traveled to Beijing in the summer of 2007 to take initial measurements of airborne particles in various spots around the city, from heavily trafficked highways to residential communities -- even inside restaurants. They used real-time analytical instruments to capture the changes in particle size and concentrations in a matter of seconds.

Zhang also is collaborating in an air quality project in Syracuse, N.Y., helping to design a controlled ventilation system for a building to be placed at the intersection of Interstates 81 and 690 -- a major hub in downtown Syracuse. The building will house the Syracuse Center of Excellence in Environmental and Energy Systems, which is funding the study.

"I think it"s novel in terms of linking the building to the surrounding environment," he said. "When people think about a building, they only think about the building alone. They never think, "The building has to be somewhere.""

He also is working on air quality studies in Rochester and in South Bronx, N.Y., where high rates of asthma in schoolchildren are believed to be caused by heavy, prolonged traffic congestion.

Early last spring, as cities worldwide were shutting down to halt the spread of COVID-19, Demaneuf, 52, began reading up on the origins of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the disease. The prevailing theory was that it had jumped from bats to some other species before making the leap to humans at a market in China, where some of the earliest cases appeared in late 2019. The Huanan wholesale market, in the city of Wuhan, is a complex of markets selling seafood, meat, fruit, and vegetables. A handful of vendors sold live wild animals—a possible source of the virus.

That wasn’t the only theory, though. Wuhan is also home to China’s foremost coronavirus research laboratory, housing one of the world’s largest collections of bat samples and bat-virus strains. The Wuhan Institute of Virology’s lead coronavirus researcher, Shi Zhengli, was among the first to identify horseshoe bats as the natural reservoirs for SARS-CoV, the virus that sparked an outbreak in 2002, killing 774 people and sickening more than 8,000 globally. After SARS, bats became a major subject of study for virologists around the world, and Shi became known in China as “Bat Woman” for her fearless exploration of their caves to collect samples. More recently, Shi and her colleagues at the WIV have performed high-profile experiments that made pathogens more infectious. Such research, known as “gain-of-function,” has generated heated controversy among virologists.

Demaneuf began searching for patterns in the available data, and it wasn’t long before he spotted one. China’s laboratories were said to be airtight, with safety practices equivalent to those in the U.S. and other developed countries. But Demaneuf soon discovered that there had been four incidents of SARS-related lab breaches since 2004, two occuring at a top laboratory in Beijing. Due to overcrowding there, a live SARS virus that had been improperly deactivated, had been moved to a refrigerator in a corridor. A graduate student then examined it in the electron microscope room and sparked an outbreak.

Demaneuf published his findings in a Medium post, titled “The Good, the Bad and the Ugly: a review of SARS Lab Escapes.” By then, he had begun working with another armchair investigator, Rodolphe de Maistre. A laboratory project director based in Paris who had previously studied and worked in China, de Maistre was busy debunking the notion that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was a “laboratory” at all. In fact, the WIV housed numerous laboratories that worked on coronaviruses. Only one of them has the highest biosafety protocol: BSL-4, in which researchers must wear full-body pressurized suits with independent oxygen. Others are designated BSL-3 and even BSL-2, roughly as secure as an American dentist’s office.

Having connected online, Demaneuf and de Maistre began assembling a comprehensive list of research laboratories in China. As they posted their findings on Twitter, they were soon joined by others around the world. Some were cutting-edge scientists at prestigious research institutes. Others were science enthusiasts. Together, they formed a group called DRASTIC, short for Decentralized Radical Autonomous Search Team Investigating COVID-19. Their stated objective was to solve the riddle of COVID-19’s origin.State Department investigators say they were repeatedly advised not to open a “Pandora’s box.”

With disreputable wing nuts on one side of them and scornful experts on the other, the DRASTIC researchers often felt as if they were on their own in the wilderness, working on the world’s most urgent mystery. They weren’t alone. But investigators inside the U.S. government asking similar questions were operating in an environment that was as politicized and hostile to open inquiry as any Twitter echo chamber. When Trump himself floated the lab-leak hypothesis last April, his divisiveness and lack of credibility made things more, not less, challenging for those seeking the truth.

Since December 1, 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 has infected more than 170 million people around the world and killed more than 3.5 million. To this day, we don’t know how or why this novel coronavirus suddenly appeared in the human population. Answering that question is more than an academic pursuit: Without knowing where it came from, we can’t be sure we’re taking the right steps to prevent a recurrence.

A months long Vanity Fair investigation, interviews with more than 40 people, and a review of hundreds of pages of U.S. government documents, including internal memos, meeting minutes, and email correspondence, found that conflicts of interest, stemming in part from large government grants supporting controversial virology research, hampered the U.S. investigation into COVID-19’s origin at every step. In one State Department meeting, officials seeking to demand transparency from the Chinese government say they were explicitly told by colleagues not to explore the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s gain-of-function research, because it would bring unwelcome attention to U.S. government funding of it.

In an internal memo obtained by Vanity Fair, Thomas DiNanno, former acting assistant secretary of the State Department’s Bureau of Arms Control, Verification, and Compliance, wrote that staff from two bureaus, his own and the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation, “warned” leaders within his bureau “not to pursue an investigation into the origin of COVID-19” because it would “‘open a can of worms’ if it continued.”

But for most of the past year, the lab-leak scenario was treated not simply as unlikely or even inaccurate but as morally out-of-bounds. In late March, former Centers for Disease Control director Robert Redfield received death threats from fellow scientists after telling CNN that he believed COVID-19 had originated in a lab. “I was threatened and ostracized because I proposed another hypothesis,” Redfield told Vanity Fair. “I expected it from politicians. I didn’t expect it from science.”

With President Trump out of office, it should be possible to reject his xenophobic agenda and still ask why, in all places in the world, did the outbreak begin in the city with a laboratory housing one of the world’s most extensive collection of bat viruses, doing some of the most aggressive research?

In the words of David Feith, former deputy assistant secretary of state in the East Asia bureau, “The story of why parts of the U.S. government were not as curious as many of us think they should have been is a hugely important one.”

On December 9, 2020, roughly a dozen State Department employees from four different bureaus gathered in a conference room in Foggy Bottom to discuss an upcoming fact-finding mission to Wuhan organized in part by the World Health Organization. The group agreed on the need to press China to allow a thorough, credible, and transparent investigation, with unfettered access to markets, hospitals, and government laboratories. The conversation then turned to the more sensitive question: What should the U.S. government say publicly about the Wuhan Institute of Virology?

As officials at the meeting discussed what they could share with the public, they were advised by Christopher Park, the director of the State Department’s Biological Policy Staff in the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation, not to say anything that would point to the U.S. government’s own role in gain-of-function research, according to documentation of the meeting obtained by Vanity Fair.Only two other labs in the world, in Texas and North Carolina, were doing similar research. “It’s not a dozen cities,” Dr. Richard Ebright said. “It’s three places.”

Some of the attendees were “absolutely floored,” said an official familiar with the proceedings. That someone in the U.S. government could “make an argument that is so nakedly against transparency, in light of the unfolding catastrophe, was…shocking and disturbing.”

Park, who in 2017 had been involved in lifting a U.S. government moratorium on funding for gain-of-function research, was not the only official to warn the State Department investigators against digging in sensitive places. As the group probed the lab-leak scenario, among other possibilities, its members were repeatedly advised not to open a “Pandora’s box,” said four former State Department officials interviewed by Vanity Fair. The admonitions “smelled like a cover-up,” said Thomas DiNanno, “and I wasn’t going to be part of it.”

Reached for comment, Chris Park told Vanity Fair, “I am skeptical that people genuinely felt they were being discouraged from presenting facts.” He added that he was simply arguing that it “is making an enormous and unjustifiable leap…to suggest that research of that kind [meant] that something untoward is going on.”

There were two main teams inside the U.S. government working to uncover the origins of COVID-19: one in the State Department and another under the direction of the National Security Council. No one at the State Department had much interest in Wuhan’s laboratories at the start of the pandemic, but they were gravely concerned with China’s apparent cover-up of the outbreak’s severity. The government had shut down the Huanan market, ordered laboratory samples destroyed, claimed the right to review any scientific research about COVID-19 ahead of publication, and expelled a team of Wall Street Journal reporters.

As questions swirled, Miles Yu, the State Department’s principal China strategist, noted that the WIV had remained largely silent. Yu, who is fluent in Mandarin, began mirroring its website and compiling a dossier of questions about its research. In April, he gave his dossier to Secretary of State Pompeo, who in turn publicly demanded access to the laboratories there.

It is not clear whether Yu’s dossier made its way to President Trump. But on April 30, 2020, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence put out an ambiguous statement whose apparent goal was to suppress a growing furor around the lab-leak theory. It said that the intelligence community “concurs with the wide scientific consensus that the COVID-19 virus was not manmade or genetically modified” but would continue to assess “whether the outbreak began through contact with infected animals or if it was the result of an accident at a laboratory in Wuhan.”

Trump’s premature statement poisoned the waters for anyone seeking an honest answer to the question of where COVID-19 came from. According to Pottinger, there was an “antibody response” within the government, in which any discussion of a possible lab origin was linked to destructive nativist posturing.

The revulsion extended to the international science community, whose “maddening silence” frustrated Miles Yu. He recalled, “Anyone who dares speak out would be ostracized.”

The idea of a lab leak first came to NSC officials not from hawkish Trumpists but from Chinese social media users, who began sharing their suspicions as early as January 2020. Then, in February, a research paper coauthored by two Chinese scientists, based at separate Wuhan universities, appeared online as a preprint. It tackled a fundamental question: How did a novel bat coronavirus get to a major metropolis of 11 million people in central China, in the dead of winter when most bats were hibernating, and turn a market where bats weren’t sold into the epicenter of an outbreak?

The paper offered an answer: “We screened the area around the seafood market and identified two laboratories conducting research on bat coronavirus.” The first was the Wuhan Center for Disease Control and Prevention, which sat just 280 meters from the Huanan market and had been known to collect hundreds of bat samples. The second, the researchers wrote, was the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

The paper came to a staggeringly blunt conclusion about COVID-19: “the killer coronavirus probably originated from a laboratory in Wuhan.... Regulations may be taken to relocate these laboratories far away from city center and other densely populated places.” Almost as soon as the paper appeared on the internet, it disappeared, but not before U.S. government officials took note.

By then, Matthew Pottinger had approved a COVID-19 origins team, run by the NSC directorate that oversaw issues related to weapons of mass destruction. A longtime Asia expert and former journalist, Pottinger purposefully kept the team small, because there were so many people within the government “wholly discounting the possibility of a lab leak, who were predisposed that it was impossible,” said Pottinger. In addition, many leading experts had either received or approved funding for gain-of-function research. Their “conflicted” status, said Pottinger, “played a profound role in muddying the waters and contaminating the shot at having an impartial inquiry.”

Peter Daszak, who repackaged U.S. government grants and allocated the funds to research institutes including the WIV, arrives there on February 3, 2021, during a fact-finding mission organized in part by the World Health Organization.By Hector RETAMAL/AFP/Getty Images.

The NSC investigators found ready evidence that China’s labs were not as safe as advertised. Shi Zhengli herself had publicly acknowledged that, until the pandemic, all of her team’s coronavirus research—some involving live SARS-like viruses—had been conducted in less secure BSL-3 and even BSL-2 laboratories.

In 2018, a delegation of American diplomats visited the WIV for the opening of its BSL-4 laboratory, a major event. In an unclassified cable, as a Washington Post columnist reported, they wrote that a shortage of highly trained technicians and clear protocols threatened the facility’s safe operations. The issues had not stopped the WIV’s leadership from declaring the lab “ready for research on class-four pathogens (P4), among which are the most virulent viruses that pose a high risk of aerosolized person-to-person transmission.”

On February 14, 2020, to the surprise of NSC officials, President Xi Jinping of China announced a plan to fast-track a new biosecurity law to tighten safety procedures throughout the country’s laboratories. Was this a response to confidential information? “In the early weeks of the pandemic, it didn’t seem crazy to wonder if this thing came out of a lab,” Pottinger reflected.

As the NSC tracked these disparate clues, U.S. government virologists advising them flagged one study first submitted in April 2020. Eleven of its 23 coauthors worked for the Academy of Military Medical Sciences, the Chinese army’s medical research institute. Using the gene-editing technology known as CRISPR, the researchers had engineered mice with humanized lungs, then studied their susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2. As the NSC officials worked backward from the date of publication to establish a timeline for the study, it became clear that the mice had been engineered sometime in the summer of 2019, before the pandemic even started. The NSC officials were left wondering: Had the Chinese military been running viruses through humanized mouse models, to see which might be infectious to humans?

Believing they had uncovered important evidence in favor of the lab-leak hypothesis, the NSC investigators began reaching out to other agencies. That’s when the hammer came down. “We were dismissed,” said Anthony Ruggiero, the NSC’s senior director for counterproliferation and biodefense. “The response was very negative.”

By the summer of 2020, Gilles Demaneuf was spending up to four hours a day researching the origins of COVID-19, joining Zoom meetings before dawn with European collaborators and not sleeping much. He began to receive anonymous calls and notice strange activity on his computer, which he attributed to Chinese government surveillance. “We are being monitored for sure,” he says. He moved his work to the encrypted platforms Signal and ProtonMail.

As they posted their findings, the DRASTIC researchers attracted new allies. Among the most prominent was Jamie Metzl, who launched a blog on April 16 that became a go-to site for government researchers and journalists examining the lab-leak hypothesis. A former executive vice president of the Asia Society, Metzl sits on the World Health Organization’s advisory committee on human genome editing and served in the Clinton administration as the NSC’s director for multilateral affairs. In his first post on the subject, he made clear that he had no definitive proof and believed that Chinese researchers at the WIV had the “best intentions.” Metzl also noted, “In no way do I seek to support or align myself with any activities that may be considered unfair, dishonest, nationalistic, racist, bigoted, or biased in any way.”

On December 11, 2020, Demaneuf—a stickler for accuracy—reached out to Metzl to alert him to a mistake on his blog. The 2004 SARS lab escape in Beijing, Demaneuf pointed out, had led to 11 infections, not four. Demaneuf was “impressed” by Metzl’s immediate willingness to correct the information. “From that time, we started working together.”“If the pandemic started as part of a lab leak, it had the potential to do to virology what Three Mile Island and Chernobyl did to nuclear science.”

Metzl, in turn, was in touch with the Paris Group, a collective of more than 30 skeptical scientific experts who met by Zoom once a month for hours-long meetings to hash out emerging clues. Before joining the Paris Group, Dr. Filippa Lentzos, a biosecurity expert at King’s College London, had pushed back online against wild conspiracies. No, COVID-19 was not a bioweapon used by the Chinese to infect American athletes at the Military World Games in Wuhan in October 2019. But the more she researched, the more concerned she became that not every possibility was being explored. On May 1, 2020, she published a careful assessment in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists describing just how a pathogen could have escaped the Wuhan Institute of Virology. She noted that a September 2019 paper in an academic journal by the director of the WIV’s BSL-4 laboratory, Yuan Zhiming, had outlined safety deficiencies in China’s labs. “Maintenance cost is generally neglected,” he had written. “Some BSL-3 laboratories run on extremely minimal operational costs or in some cases none at all.”

Alina Chan, a young molecular biologist and postdoctoral fellow at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard University, found that early sequences of the virus showed very little evidence of mutation. Had the virus jumped from animals to humans, one would expect to see numerous adaptations, as was true in the 2002 SARS outbreak. To Chan, it appeared that SARS-CoV-2 was already “pre-adapted to human transmission,” she wrote in a preprint paper in May 2020.

One day last May, he fished up a thesis from 2013 written by a master’s student in Kunming, China. The thesis opened an extraordinary window into a bat-filled mine shaft in Yunnan province and raised sharp questions about what Shi Zhengli had failed to mention in the course of making her denials.

The hospital called in a pulmonologist, Zhong Nanshan, who had played a prominent role in treating SARS patients and would go on to lead an expert panel for China’s National Health Commission on COVID-19. Zhong, according to the 2013 master’s thesis, immediately suspected a viral infection. He recommended a throat culture and an antibody test, but he also asked what kind of bat had produced the guano. The answer: the rufous horseshoe bat, the same species implicated in the first SARS outbreak.

A memorial for Dr. Li Wenliang, who was celebrated as a whistleblower in China after sounding the alarm about COVID-19 in January 2020. He later died of the disease.By Mark RALSTON/AFP/Getty Images.

But there was a mystery at the heart of the diagnosis. Bat coronaviruses were not known to harm humans. What was so different about the strains from inside the cave? To find out, teams of researchers from across China and beyond traveled to the abandoned mine shaft to collect viral samples from bats, musk shrews, and rats.

On February 3, 2020, with the COVID-19 outbreak already spreading beyond China, Shi Zhengli and several colleagues published a paper noting that the SARS-CoV-2 virus’s genetic code was almost 80% identical to that of SARS-CoV, which caused the 2002 outbreak. But they also reported that it was 96.2% identical to a coronavirus sequence in their possession called RaTG13, which was previously detected in “Yunnan province.” They concluded that RaTG13 was the closest known relative to SARS-CoV-2.

In the following months, as researchers around the world hunted for any known bat virus that might be a progenitor of SARS-CoV-2, Shi Zhengli offered shifting and sometimes contradictory accounts of where RaTG13 had come from and when it was fully sequenced. Searching a publicly available library of genetic sequences, several teams, including a group of DRASTIC researchers, soon realized that RaTG13 appeared identical to RaBtCoV/4991—the virus from the shaft where the miners fell ill in 2012 with what looked like COVID-19.

Their questions multiplied the following month when Shi, Daszak, and their colleagues published an account of 630 novel coronaviruses they had sampled between 2010 and 2015. Combing through the supplementary data, DRASTIC researchers were stunned to find eight more viruses from the Mojiang mine that were closely related to RaTG13 but had not been flagged in the account. Alina Chan of the Broad Institute said it was “mind-boggling” that these crucial puzzle pieces had been buried without comment.

But when Redfield saw the breakdown of early cases, some of which were family clusters, the market explanation made less sense. Had multiple family members gotten sick via contact with the same animal? Gao assured him there was no human-to-human transmission, says Redfield, who nevertheless urged him to test more widely in the community. That effort prompted a tearful return call. Many cases had nothing to do with the market, Gao admitted. The virus appeared to be jumping from person to person, a far scarier scenario.

Redfield immediately thought of the Wuhan Institute of Virology. A team could rule it out as a source of the outbreak in just a few weeks, by testing researchers there for antibodies. Redfield formally reiterated his offer to send specialists, but Chinese officials didn’t respond to his overture.

In the ensuing uproar, scientists battled over the risks and benefits of such research. Those in favor claimed it could help prevent pandemics, by highlighting potential risks and accelerating vaccine development. Critics argued that creating pathogens that didn’t exist in nature ran the risk of unleashing them.

In October 2014, the Obama administration imposed a moratorium on new funding for gain-of-function research projects that could make influenza, MERS, or SARS viruses more virulent or transmissible. But a footnote to the statement announcing the moratorium carved out an exception for cases deemed “urgently necessary to protect the public health or national security.”

In the first year of the Trump administration, the moratorium was lifted and replaced with a review system called the HHS P3CO Framework (for Potential Pandemic Pathogen Care and Oversight). It put the onus for ensuring the safety of any such research on the federal department or agency funding it. This left the review process shrouded in secrecy. “The names of reviewers are not released, and the details of the experiments to be considered are largely secret,” said the Harvard epidemiologist Dr. Marc Lipsitch, whose advocacy against gain-of-function research helped prompt the moratorium. (An NIH spokesperson told Vanity Fair that “information about individual unfunded applications is not public to preserve confidentiality and protect sensitive information, preliminary data, and intellectual property.”)

Inside the NIH, which funded such research, the P3CO framework was largely met with shrugs and eye rolls, said a longtime agency official: “If you ban gain-of-function research, you ban all of virology.” He added, “Ever since the moratorium, everyone’s gone wink-wink and just done gain-of-function research anyway.”

British-born Peter Daszak, 55, is the president of EcoHealth Alliance, a New York City–based nonprofit with the laudable goal of preventing the outbreak of emerging diseases by safeguarding ecosystems. In May 2014, five months before the moratorium on gain-of-function research was announced, EcoHealth secured a NIAID grant of roughly $3.7 million, which it allocated in part to various entities engaged in collecting bat samples, building models, and performing gain-of-function experiments to see which animal viruses were able to jump to humans. The grant was not halted under the moratorium or the P3CO framework.

As the pandemic raged, the collaboration between EcoHealth Alliance and the WIV wound up in the crosshairs of the Trump administration. At a White House COVID-19 press briefing on April 17, 2020, a reporter from the conspiratorial right-wing media outlet Newsmax asked Trump a factually inaccurate question about a $3.7 million NIH grant to a level-four lab in China. “Why would the U.S. give a grant like that to China?” the reporter asked.

A week later, an NIH official notified Daszak in writing that his grant had been terminated. The order had come from the White House, Dr. Anthony Fauci later testified before a congressional committee. The decision fueled a firestorm: 81 Nobel Laureates in science denounced the decision in an open letter to Trump health officials, and 60 Minutes ran a segment focused on the Trump administration’s shortsighted politicization of science.

Daszak appeared to be the victim of a political hit job, orchestrated to blame China, Dr. Fauci, and scientists in general for the pandemic, while distracting from the Trump administration’s bungled response. “He’s basically a wonderful, decent human being” and an “old-fashioned altruist,” said the NIH official. “To see this happening to him, it really kills me.”

But conspiracy-minded conservatives weren’t the only ones looking askance at Daszak. Ebright likened Daszak’s model of research—bringing samples from a remote area to an urban one, then sequencing and growing viruses and attempting to genetically modify them to make them more virulent—to “looking for a gas leak with a lighted match.” Moreover, Ebright believed that Daszak’s research had failed in its stated purpose of predicting and preventing pandemics through its global collaborations.

Under the subject line, “No need for you to sign the “Statement” Ralph!!,” he wrote to two scientists, including UNC’s Dr. Ralph Baric, who had collaborated with Shi Zhengli on the gain-of-function study that created a coronavirus capable of infecting human cells: “you, me and him should not sign this statement, so it has some distance from us and therefore doesn’t work in a counterproductive way.” Daszak added, “We’ll then put it out in a way that doesn’t link it back to our collaboration so we maximize an independent voice.”

Baric did not sign the statement. In the end, Daszak did. At least six other signers had either worked at, or had been funded by, EcoHealth Alliance. The statement ended with a declaration of objectivity: “We declare no competing interests.”

Daszak mobilized so quickly for a reason, said Jamie Metzl: “If zoonosis was the origin, it was a validation…of his life work…. But if the pandemic started as part of a lab leak, it had the potential to do to virology what Three Mile Island and Chernobyl did to nuclear science.” It could mire the field indefinitely in moratoriums and funding restrictions.

By the summer of 2020, the State Department’s COVID-19 origins investigation had gone cold. Officials in the Bureau of Arms Control, Verification, and Compliance went back to their normal work: surveilling the world for biological threats. “We weren’t looking for Wuhan,” said Thomas DiNanno. That fall, the State Department team got a tip from a foreign source: Key information was likely sitting in the U.S. intelligence community’s own files, unanalyzed. In November, that lead turned up classified information that was “absolutely arresting and shocking,” said a former State Department official. Three researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, all connected with gain-of-function research on coronaviruses, had fallen ill in November 2019 and appeared to have visited the hospital with symptoms similar to COVID-19, three government officials told Vanity Fair.

An intelligence analyst working with David Asher sifted through classified channels and turned up a report that outlined why the lab-leak hypothesis was plausible. It had been written in May by researchers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which performs national security research for the Department of Energy. But it appeared to have been buried within the classified collections system.

Now the officials were beginning to suspect that someone was actually hiding materials supportive of a lab-leak explanation. “Why did my contractor have to pore through documents?” DiNanno wondered. Their suspicion intensified when Department of Energy officials overseeing the Lawrence Livermore lab unsuccessfully tried to block the State Department investigators from talking to the report’s authors.

Their frustration crested in December, when they finally briefed Chris Ford, acting undersecretary for Arms Control and International Security. He seemed so hostile to their probe that they viewed him as a blinkered functionary bent on whitewashing China’s malfeasance. But Ford, who had years of experience in nuclear nonproliferation, had long been a China hawk. Ford told Vanity Fair that he saw his job as protecting the integrity of any inquiry into COVID-19’s origins that fell under his purview. Going with “stuff that makes us look like the crackpot brigade” would backfire, he believed.

There was another reason for his hostility. He’d already heard about the investigation from interagency colleagues, rather than from the team itself, and the secrecy left him with a “spidey sense” that the process was a form of “creepy freelancing.” He wondered: Had someone launched an unaccountable investigation with the goal of achieving a desired result?

He was not the only one with concerns. As one senior government official with knowledge of the State Department’s investigation said, “They were writing this for certain customers in the Trump administration. We asked for the reporting behind the statements that were made. It took forever. Then you’d read the report, it would have this reference to a tweet and a date. It was not something you could go back and find.”

Though they questioned Quay’s findings, the scientists saw other reasons to suspect a lab origin. Part of the WIV’s mission was to sample the natural world and provide early warnings of “human capable viruses,” said Relman. The 2012 infections of six miners was “worthy of banner headlines at the time.” Yet those cases had never been reported to the WHO.

Baric added that, if SARS-CoV-2 had come from a “strong animal reservoir,” one might have expected to see “multiple introduction events,” rather than a single outbreak, though he cautioned that it didn’t prove “[this] was an escape from a laboratory.” That prompted Asher to ask, “Could this not have been partially bioengineered?”

In the memo, Ford criticized the panel’s “lack of data” and added, “I would also caution you against suggesting that there is anything inherently suspicious—and suggestive of biological warfare activity—about People’s Liberation Army (PLA) involvement at WIV on classified projects. [I]t would be difficult to say that military involvement in classified virus research is intrinsically problematic, since the U.S. Army has been deeply involved in virus research in the United States for many years.”

Thomas DiNanno sent back a five-page rebuttal to Ford’s memo the next day, January 9 (though it was mistakenly dated “12/9/21”). He accused Ford of misrepresenting the panel’s efforts and enumerated the obstacles his team had faced: “apprehension and contempt” from the technical staff; warnings not to investigate the origins of COVID-19 for fear of opening a “can of worms”; and a “complete lack of responses to briefings and presentations.” He added that Quay had been invited only after the National Intelligence Council failed to provide statistical help.

The State Department investigators pushed on, determined to go public with their concerns. They continued a weeks-long effort to declassify information that had been vetted by the intelligence community. On January 15, five days before President Joe Biden’s swearing in, the State Department released a fact sheet about activity at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, disclosing key information: that several researchers there had fallen ill with COVID-19-like symptoms in autumn 2019, before the first identified outbreak case; and that researchers there had collaborated on secret projects with China’s military and “engaged in classified research, including laboratory animal experiments, on behalf of the Chinese military since at least 2017.”

The statement withstood “aggressive suspicion,” as one former State Department official said, and the Biden administration has not walked it back. “I was very pleased to see Pompeo’s statement come through,” said Chris Ford, who personally signed off on a draft of the fact sheet before leaving the State Department. “I was so relieved that they were using real reporting that had been vetted and cleared.”

In early July, the World Health Organization invited the U.S. government to recommend experts for a fact-finding mission to Wuhan, a sign of progress in the long-delayed probe of COVID-19’s origins. Questions about the WHO’s independence from China, the country’s secrecy, and the raging pandemic had turned the anticipated mission into a minefield of international grudges and suspicion.

It had been evident from the start that China would control who could come and what they could see. In July, when the WHO sent member countries a draft of the terms governing the mission, the PDF document was titled, “CHN and WHO agreed final version,” suggesting that China had preapproved its contents.

Part of the fault lay with the Trump administration, which had failed to counter China’s control over the scope of the mission when it was being hammered out two months earlier. The resolution, forged at the World Health Assembly, called not for a full inquiry into the origins of the pandemic but instead for a mission “to identify the zoonotic source of the virus.” The natural-origin hypothesis was baked into the enterprise. “It was a huge difference that only the Chinese understood,” said Jamie Metzl. “While the [Trump] administration was huffing and puffing, some really important things were happening around the WHO, and the U.S. didn’t have a voice.”

On January 14, 2021, Daszak and 12 other international experts arrived in Wuhan to join 17 Chinese experts and an entourage of government minders. They spent two weeks of the monthlong mission quarantined in their hotel rooms. The remaining two-week inquiry was more propaganda than probe, complete with a visit to an exhibit extolling President Xi’s leadership. The team saw almost no raw data, only the Chinese government analysis of it.

They paid one visit to the Wuhan Institute of Virology, where they met with Shi Zhengli, as recounted in an annex to the mission report. One obvious demand would have been access to the WIV’s database of some 22,000 virus samples and sequences, which had been taken offline. At an event convened by a London organization on March 10, Daszak was asked whether the group had made such a request. He said there was no need: Shi Zhengli had stated that the WIV took down the database due to hacking attempts during the pandemic. “Absolutely reasonable,” Daszak said. “And we did not ask to see the data…. As you know, a lot of this work has been conducted with EcoHealth Alliance…. We do basically know what’s in those databases. There is no evidence of viruses closer to SARS-CoV-2 than RaTG13 in those databases, simple as that.”

After two weeks of fact finding, the Chinese and international experts concluded their mission by voting with a show of hands on which origin scenario seemed most probable. Direct transmission from bat to human: possible to likely. Transmission through an intermediate animal: likely to very likely. Transmission through frozen food: possible. Transmission through a laboratory incident: extremely unlikely.

On March 30, 2021, media outlets around the world reported on the release of the mission’s 120-page report. Discussion of a lab leak took up less than two pages. Calling the report “fatally flawed,” Jamie Metzl tweeted: “They set out to prove one hypothesis, not fairly examine all of them.”

An internal U.S. government analysis of the mission’s report, obtained by Vanity Fair, found it to be inaccurate and even contradictory, with some sections undermining conclusions made elsewhere and others relying on reference papers that had been withdrawn. Regarding the four possible origins, the analysis stated, the report “does not include a description of how these hypotheses were generated, would be tested, or how a decision would be made between them to decide that one is more likely than another.” It added that a possible laboratory incident received only a “cursory” look, and the “evidence presented seems insufficient to deem the hypothesis ‘extremely unlikely.’”

By then, an international coalition of roughly two dozen scientists, among them DRASTIC researcher Gilles Demaneuf and EcoHealth critic Richard Ebright at Rutgers, had found a way around what Metzl described as a “wall of rejections” by scientific journals. With Metzl’s guidance, they began publishing open letters in early March. Their second letter, issued on April 7, condemned the mission report and called for a full investigation into the origin of COVID-19. It was picked up widely by national newspapers.

A growing number of people were demanding to know what exactly had gone on inside the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Were the claims in the State Department’s fact sheet—of sick researchers and secret military research—accurate?

Metzl had managed to question Shi directly a week before the release of the mission report. At a March 23 online lecture by Shi, hosted by Rutgers Medical School, Metzl asked if she had full knowledge of all the research being done at the WIV and all the viruses held there, and if the U.S. government was correct that classified military research had taken place. She responded:We—our work, our research is open, and we have a lot of international collaboration. And from my knowledge, all our research work is open, is transparency. So, at the beginning of COVID-19, we heard the rumors that it’s claimed in our laboratory we have some project, blah blah, with army, blah blah, these kinds of rumors. But this is not correct because I am the lab’s director and responsible for research activity. I don’t know any

8613371530291

8613371530291