mud pump power end parts free sample

Fluid-End Modules . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Mud-Pump Gear Sets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

The 2,200-hp mud pump for offshore applications is a single-acting reciprocating triplex mud pump designed for high fluid flow rates, even at low operating speeds, and with a long stroke design. These features reduce the number of load reversals in critical components and increase the life of fluid end parts.

The pump’s critical components are strategically placed to make maintenance and inspection far easier and safer. The two-piece, quick-release piston rod lets you remove the piston without disturbing the liner, minimizing downtime when you’re replacing fluid parts.

FET manufactures a full range of valves and seats for every drilling and well-servicing application as part of our full line of Osprey® mud pump system solutions. All of our valves and seats can be used in water, water base, oil base and synthetic base mud applications. FET offers additional valves and seats not listed below, including drilling valves, frac valves and well service valves. FET’s QC standards for the dimensional and material specs are extremely rigid in comparison to other manufacturers. Contact your FET representative to learn more.

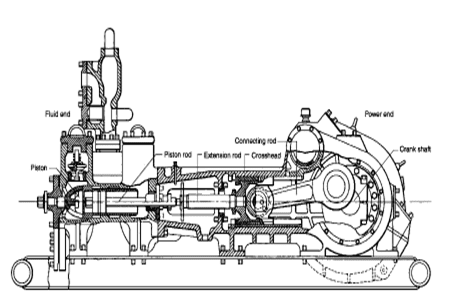

Triplex mud pumps pump drilling mud during well operations. An example of a typical triplex mud pump 10 shown in FIG. 1A has a power assembly 12, a crosshead assembly 14, and a fluid assembly 16. Electric motors (not shown) connect to a pinion shaft 30 that drives the power assembly 12. The crosshead assembly 14 converts the rotational movement of the power assembly 12 into reciprocating movement to actuate internal pistons or plungers of the fluid assembly 16. Being triplex, the pump"s fluid assembly 16 has three internal pistons to pump the mud.

As shown in FIG. 1B, the pump"s power assembly 14 has a crankshaft 20 supported at its ends by double roller bearings 22. Positioned along its intermediate extent, the crankshaft 20 has three eccentric sheaves 24-1 . . . 24-3, and three connecting rods 40 mount onto these sheaves 24 with cylindrical roller bearings 26. These connecting rods 40 connect by extension rods (not shown) and the crosshead assembly (14) to the pistons of the pump"s fluid assembly 16.

In addition to the sheaves, the crankshaft 20 also has a bull gear 28 positioned between the second and third sheaves 24-2 and 24-3. The bull gear 28 interfaces with the pinion shaft (30) and drives the crankshaft 20"s rotation. As shown particularly in FIG. 1C, the pinion shaft 30 also mounts in the power assembly 14 with roller bearings 32 supporting its ends. When electric motors couple to the pinion shaft"s ends 34 and rotate the pinion shaft 30, a pinion gear 38 interfacing with the crankshaft"s bull gear 28 drives the crankshaft (20), thereby operating the pistons of the pump"s fluid assembly 16.

When used to pump mud, the triplex mud pump 10 produces flow that varies by approximately 23%. For example, the pump 10 produces a maximum flow level of about 106% during certain crankshaft angles and produces a minimum flow level of 83% during other crankshaft angles, resulting in a total flow variation of 23% as the pump"s pistons are moved in differing exhaust strokes during the crankshaft"s rotation. Because the total flow varies, the pump 10 tends to produce undesirable pressure changes or “noise” in the pumped mud. In turn, this noise interferes with downhole telemetry and other techniques used during measurement-while-drilling (MWD) and logging-while-drilling (LWD) operations.

In contrast to mud pumps, well-service pumps (WSP) are also used during well operations. A well service pump is used to pump fluid at higher pressures than those used to pump mud. Therefore, the well service pumps are typically used to pump high pressure fluid into a well during frac operations or the like. An example of a well-service pump 50 is shown in FIG. 2. Here, the well service pump 50 is a quintuplex well service pump, although triplex well service pumps are also used. The pump 50 has a power assembly 52, a crosshead assembly 54, and a fluid assembly 56. A gear reducer 53 on one side of the pump 50 connects a drive (not shown) to the power assembly 52 to drive the pump 50.

As shown in FIG. 3, the pump"s power assembly 52 has a crankshaft 60 with five crankpins 62 and an internal main bearing sheave 64. The crankpins 62 are offset from the crankshaft 60"s axis of rotation and convert the rotation of the crankshaft 60 in to a reciprocating motion for operating pistons (not shown) in the pump"s fluid assembly 56. Double roller bearings 66 support the crankshaft 60 at both ends of the power assembly 52, and an internal double roller bearing 68 supports the crankshaft 60 at its main bearing sheave 64. One end 61 of the crankshaft 60 extends outside the power assembly 52 for coupling to the gear reducer (53; FIG. 2) and other drive components.

As shown in FIG. 4A, connecting rods 70 connect from the crankpins 62 to pistons or plungers 80 via the crosshead assembly 54. FIG. 4B shows a typical connection of a connecting rod 70 to a crankpin 62 in the well service pump 50. As shown, a bearing cap 74 fits on one side of the crankpin 62 and couples to the profiled end of the connecting rod 70. To reduce friction, the connection uses a sleeve bearing 76 between the rod 70, bearing cap 74, and crankpin 62. From the crankpin 62, the connecting rod 70 connects to a crosshead 55 using a wrist pin 72 as shown in FIG. 4A. The wrist pin 72 allows the connecting rod 70 to pivot with respect to the crosshead 55, which in turn is connected to the plunger 80.

In use, an electric motor or an internal combustion engine (such as a diesel engine) drives the pump 50 by the gear reducer 53. As the crankshaft 60 turns, the crankpins 62 reciprocate the connecting rods 70. Moved by the rods 70, the crossheads 55 reciprocate inside fixed cylinders. In turn, the plunger 80 coupled to the crosshead 55 also reciprocates between suction and power strokes in the fluid assembly 56. Withdrawal of a plunger 80 during a suction stroke pulls fluid into the assembly 56 through the input valve 82 connected to an inlet hose or pipe (not shown). Subsequently pushed during the power stroke, the plunger 80 then forces the fluid under pressure out through the output valve 84 connected to an outlet hose or pipe (not shown).

In contrast to using a crankshaft for a quintuplex well-service pump that has crankpins 62 as discussed above, another type of quintuplex well-service pump uses eccentric sheaves on a direct drive crankshaft. FIG. 4C is an isolated view of such a crankshaft 90 having eccentric sheaves 92-1 . . . 92-5 for use in a quintuplex well-service pump. External main bearings (not shown) support the crankshaft 90 at its ends 96 in the well-service pumps housing (not shown). To drive the crankshaft 90, one end 91 extends beyond the pumps housing for coupling to drive components, such as a gear box. The crankshaft 90 has five eccentric sheaves 92-1 . . . 92-5 for coupling to connecting rods (not shown) with roller bearings. The crankshaft 90 also has two internal main bearing sheaves 94-1, 94-2 for internal main bearings used to support the crankshaft 90 in the pump"s housing.

In the past, quintuplex well-service pumps used for pumping frac fluid or the like have been substituted for mud pumps during drilling operations to pump mud. Unfortunately, the well-service pump has a shorter service life compared to the conventional triplex mud pumps, making use of the well-service pump as a mud pump less desirable in most situations. In addition, a quintuplex well-service pump produces a great deal of white noise that interferes with MWD and LWD operations, further making the pump"s use to pump mud less desirable in most situations. Furthermore, the well-service pump is configured for direct drive by a motor and gear box directly coupling on one end of the crankshaft. This direct coupling limits what drives can be used with the pump. Moreover, the direct drive to the crankshaft can produce various issues with noise, balance, wear, and other associated problems that make use of the well-service pump to pump mud less desirable.

One might expect to provide a quintuplex mud pump by extending the conventional arrangement of a triplex mud pump (e.g., as shown in FIG. 1B) to include components for two additional pistons or plungers. However, the actual design for a quintuplex mud pump is not as easy as extending the conventional arrangement, especially in light of the requirements for a mud pump"s operation such as service life, noise levels, crankshaft deflection, balance, and other considerations. As a result, acceptable implementation of a quintuplex mud pump has not been achieved in the art during the long history of mud pump design.

What is needed is an efficient mud pump that has a long service life and that produces low levels of white noise during operation so as not to interfere with MWD and LWD operations while pumping mud in a well.

A quintuplex mud pump is a continuous duty, reciprocating plunger/piston pump. The mud pump has a crankshaft supported in the pump by external main bearings and uses internal gearing and a pinion shaft to drive the crankshaft. Five eccentric sheaves and two internal main bearing sheaves are provided on the crankshaft. Each of the main bearing sheaves supports the intermediate extent of crankshaft using bearings. One main bearing sheave is disposed between the second and third eccentric sheaves, while the other main bearing sheave is disposed between the third and fourth eccentric sheaves.

One or more bull gears are also provided on the crankshaft, and the pump"s pinion shaft has one or more pinion gears that interface with the one or more bull gears. If one bull gear is used, the interface between the bull and pinion gears can use herringbone or double helical gearing of opposite hand to avoid axial thrust. If two bull gears are used, the interface between the bull and pinion gears can use helical gearing with each having opposite hand to avoid axial thrust. For example, one of two bull gears can be disposed between the first and second eccentric sheaves, while the second bull gear can be disposed between fourth and fifth eccentric sheaves. These bull gears can have opposite hand. The pump"s internal gearing allows the pump to be driven conventionally and packaged in any standard mud pump packaging arrangement. Electric motors (for example, twin motors made by GE) may be used to drive the pump, although the pump"s rated input horsepower may be a factor used to determine the type of motor.

Connecting rods connect to the eccentric sheaves and use roller bearings. During rotation of the crankshaft, these connecting rods transfer the crankshaft"s rotational movement to reciprocating motion of the pistons or plungers in the pump"s fluid assembly. As such, the quintuplex mud pump uses all roller bearings to support its crankshaft and to transfer crankshaft motion to the connecting rods. In this way, the quintuplex mud pump can reduce the white noise typically produced by conventional triplex mud pumps and well service pumps that can interfere with MWD and LWD operations.

Turning to the drawings, a quintuplex mud pump 100 shown in FIGS. 5 and 6A-6B has a power assembly 110, a crosshead assembly 150, and a fluid assembly 170. Twin drives (e.g., electric motors, etc.) couple to ends of the power assembly"s pinion shaft 130 to drive the pump"s power assembly 110. As shown in FIGS. 6A-6B, internal gearing within the power assembly 110 converts the rotation of the pinion shaft 130 to rotation of a crankshaft 120. The gearing uses pinion gears 138 on the pinion shaft 130 that couple to bull gears 128 on the crankshaft 120 and transfer rotation of the pinion shaft 130 to the crankshaft 120.

For support, the crankshaft 120 has external main bearings 122 supporting its ends and two internal main bearings 127 supporting its intermediate extent in the assembly 110. As best shown in FIG. 6A, rotation of the crankshaft 120 reciprocates five independent connecting rods 140. Each of the connecting rods 140 couples to a crosshead 160 of the crosshead assembly 150. In turn, each of the crossheads 160 converts the connecting rod 40"s movement into a reciprocating movement of an intermediate pony rod 166. As it reciprocates, the pony rod 166 drives a coupled piston or plunger (not shown) in the fluid assembly 170 that pumps mud from an intake manifold 192 to an output manifold 198. Being quintuplex, the mud pump 100 has five such pistons movable in the fluid assembly 170 for pumping the mud.

Preferably, each of the sheaves 124-1 . . . 124-5, bull gear supports 128-1 &128-2, and bearing sheaves 125-1 &125-2 are equidistantly spaced on the crankshaft 120 for balance. In one implementation for the crankshaft 120 having a length a little greater than 90-in. (e.g., 90.750-in.), each of the sheaves 124, 125 and supports 128 are equidistantly spaced from one another by 9-inches between their rotational centers. The end sheaves 124-1 and 124-5 can be positioned a little over 9-in. (e.g., 9.375-in.) from the ends of the crankshaft 120.

The additional detail of FIG. 8 shows the crankshaft 120 supported in the power assembly 110 and having the connecting rods 140 mounted thereon. As noted above, double roller bearings 122 support the ends of the crankshaft 120 in the assembly 110. Internally, main bearings 123 support the intermediate extent of the crankshaft 120 in the assembly 110. In particular, the main bearings 126 position on the main bearing sheaves 125-1 and 125-2 and are supported by carriers 125 mounted to the assembly 110 at 129. The external main bearings 122 are preferably spherical bearings to better support radial and axial loads. The internal main bearings 125 preferably use cylindrical bearings.

Five connector rods 140 use roller bearings 126 to fit on the eccentric sheaves 124-1 . . . 124-5. Each of the roller bearings 126 preferably uses cylindrical bearings. The rods 140 extend from the sheaves 124-1 . . . 124-5 (perpendicular to the figure) and couple the motion of the crankshaft 120 to the fluid assembly (170) via crossheads (160) as is discussed in more detail below with reference to FIGS. 10A-10B.

As shown in FIG. 9, the pinion shaft 130 mounts with roller bearings 132 in the power assembly 110 with its free ends 134 extending on both sides of the assembly 110 for coupling to drive components (not shown). As noted previously, the pinion gears 138 on the shaft 130 interface with the bull gears 128 on the crankshaft (120). Preferably, the interface uses helical gearing of opposite hand. In particular, the two pinion gears 138 on the pinion shaft 130 have helical teeth that have an opposite orientation or hand relative to one another. These helical teeth couple in parallel fashion to oppositely oriented helical teeth on the complementary bull gears 128 on the crankshaft 120. (The opposing orientation of helical teeth on the bull gears 128 and pinion gears 138 can best be seen in FIGS. 6A-6B). The helical gearing transfers rotation of the pinion shaft 130 to the crankshaft 120 in a balanced manner. In an alternative embodiment, the pinion shaft 130 can have one pinion gear 138, and the crankshaft 120 can have one bull gear 128. Preferably, these single gears 138/128 use herringbone or double helical gearing of opposite hand to avoid imparting axial thrust to the crankshaft 120.

The cross-section in FIG. 10A shows a crosshead 160 for the quintuplex mud pump. The end of the connecting rod 140 couples by a wrist pin 142 and bearing 144 to a crosshead body 162 that is movable in a crosshead guide 164. A pony rod 166 coupled to the crosshead body 162 extends through a stuffing box gasket 168 on a diaphragm plate 169. An end of this pony rod 166 in turn couples to additional components of the fluid assembly (170) as discussed below.

The cross-section in FIG. 10B shows portion of the fluid assembly 170 for the quintuplex mud pump. An intermediate rod 172 has a clamp 174 that couples to the pony rod (166; FIG. 10A) from the crosshead assembly 160 of FIG. 10A. The opposite end of the rod 172 couples by another clamp to a piston rod 180 having a piston head 182 on its end. Although a piston arrangement is shown, the fluid assembly 170 can use a plunger or any other equivalent arrangement so that the terms piston and plunger can be used interchangeably herein. Moved by the pony rod (166), the piston head 182 moves in a liner 184 communicating with a fluid passage 190. As the piston 182 moves, it pulls mud from a suction manifold 192 through a suction valve 194 into the passage 190 and pushes the mud in the passage 190 to a discharge manifold 198 through a discharge valve 196.

As noted previously, a triplex mud pump produces a total flow variation of about 23%. Because the present mud pump 100 is quintuplex, the pump 100 offers a lower variation in total flow, making the pump 100 better suited for pumping mud and producing less noise that can interfere with MWD and LWD operations. In particular, the quintuplex mud pump 100 can produce a total flow variation as low as about 7%. For example, the quintuplex mud pump 100 can produce a maximum flow level of about 102% during certain crankshaft angles and can produce a minimum flow level of 95% during other crankshaft angles as the pump"s five pistons move in their differing strokes during the crankshaft"s rotation. Being smoother and closer to ideal, the lower total flow variation of 7% produces less pressure changes or “noise” in the pumped mud that can interfere with MWD and LWD operations.

Although a quintuplex mud pump is described above, it will be appreciated that the teachings of the present disclosure can be applied to multiplex mud pumps having at least more than three eccentric sheaves, connecting rods, and fluid assembly pistons. Preferably, the arrangement involves an odd number of these components so such mud pumps may be septuplex, nonuplex, etc. For example, a septuplex mud pump according to the present disclosure may have seven eccentric sheaves, connecting rods, and fluid assembly pistons with at least two bull gears and at least two bearing sheaves on the crankshaft. The bull gears can be arranged between first and second eccentric sheaves and sixth and seventh eccentric sheaves on the crankshaft. The internal main bearings supporting the crankshaft can be positioned between third and fourth eccentric sheaves and the fourth and fifth eccentric sheaves on the crankshaft.

The foregoing description of preferred and other embodiments is not intended to limit or restrict the scope or applicability of the inventive concepts conceived of by the Applicants. In exchange for disclosing the inventive concepts contained herein, the Applicants desire all patent rights afforded by the appended claims. Therefore, it is intended that the appended claims include all modifications and alterations to the full extent that they come within the scope of the following claims or the equivalents thereof.

We are committed to total customer satisfaction, achieving excellence in our operations through continuous improvement, development and empowerment of our people, and providing a positive contribution to our community.

Adjust or replace these bearings at first sign of wear. The bearings in the crank end are babbitt lined steel shells, adjustable for wear by removing shims and easily replaced when completely worn. These bearings should be watched closely and adjusted at first signs of looseness.. You will note on series 3400, 3800, 3500, and 3900 pumps, that the shims do not completely fill the outer gap between rod and cap casting, although the connecting rod bolts are tight. This is because the faces of the shell bearings project slightly beyond the faces of the rod and cap castings, and the shims are gripped only between the faces of the bearing halves. Do not try to close this outer gap by tightening the connecting rod bolt as it will put an excessive strain on the bolts.

To check for wear, place a wrench on the top connecting rod bolt and shake the rod parallel to the crankshaft. (The pressure must be relieved from the liquid end of the pump, so that the pump"s mechanism is free to move.) If the rod bearing moves without resistance, the bearing may be too loose and need adjusting. If the bearing does need adjusting, remove shims until you cannot shake the rod, then add .005" shims one at a time until there is little side movement. Be sure to torque rod bolt nuts to proper value for each adjustment. Oil clearance should be checked with Plastigage (available in most parts stores). Wipe crankshaft journal clean of any oil, place a strip of Plastigage on the crankshaft journal and tighten rod cap to the proper torque value. Once tightened, remove rod cap and measure oil clearance with scale on Plastigage package. See oil clearance chart. (NOTE: If you are making this adjustment after having had the crossheads out, be sure that the oil holes in the rod are pointing up. The "up" side is indicated by matching numbers stamped on the cap and rod at the split between them. These numbers should be the same on each rod and should be on the top side of the crankshaft.) Rotate the shaft by hand and if there is any hard drag or tight spots in the bearing, add another 0.005" shim. After this bearing is properly adjusted, loosen bolts a few turns and repeat the above operation on the other bearings. After all bearings have been adjusted.

Torque all connecting rod bolt nuts back to proper value. Again rotate the pump by hand to check for excessive drag and tight spots. If none, the pump should be ready for operation.

If the pump cannot be rotated by hand due to the drive being enclosed, care must-be taken: not to over-tighten the bearings, since they cannot be checked by rotating the pump. When bearings are adjusted by this method, watch carefully for overheating when the pump is put into operation.

It is usually better to have a bearing a little too loose than too tight. A slightly loose bearing will cause very little trouble because of the slow operating speeds of the pump, but a tight bearing will overheat and the babbitt may melt or pull. Normal precautions must be taken to insure cleanliness of parts upon their assembly.

Inspect connecting rod bearings and adjust as necessary every six months or when crankcase lubricant is changed. The bearings in the crank end are babbitt lined steel shells, adjustable for wear by removing shims and easily replaced when completely worn. These bearings should be watched closely and adjusted to compensate for wear. You will note that shims do not completely fill the outer gap between rod and cap casting although the connecting rod bolts are tight. This is because the faces of the shell bearings project slightly beyond the faces of the rod and cap castings and the shims are gripped only between the faces of the bearing halves. Do not try to close this outer gap by tightening the connecting rod bolt as it will put an excessive strain on them.

To check for wear, place a wrench on the top connecting rod bolt and shake the rod parallel to the crankshaft. (The pressure must be relieved from the liquid end of the pump so that the pump"s mechanism is free to move.) If the rod bearing moves without resistance, the bearing may be too loose and need adjusting. If the bearing does need adjusting, remove shims until you cannot shake the rod, then add .005" shims one at a time until there is a little side movement. Be sure to torque rod bolt nuts to proper value for each adjustment. (NOTE: If you are making this adjustment after having had the crossheads out, be sure that the oil holes in the rod are pointing up. The "up" side is indicated by matching numbers stamped on the cap and rod at the split between them. These numbers should be the same on each rod and should be on the top side of the crankshaft.) Turn the shaft by hand and if there is any hard drag or tight spots in the bearing, add another .005"" shim. After this bearing is properly adjusted, loosen bolts a few turns and repeat the above operation on the other bearings. After all bearings have been adjusted, torque all connecting rod bolt nuts back to proper amount. Again turn the pump by hand to check for excessive drag and tight spots. If none, the pump should then be ready for operation.

If the pump cannot be rotated by hand due to the drive being enclosed, the bearings may be completely adjusted by shaking the bearing on the shaft as stated above. Care must be taken not to over-tighten the bearings since they cannot be checked by rotating the pump by hand. When bearings are adjusted by this method, they must be watched carefully for overheating when the pump is put into operation.

Alternatively, plastic gauge strips, found in most parts stores may be used to adjust these bearings. It is usually better to have a bearing a little too loose than too tight. A slightly loose bearing will cause very little trouble because of the slow operating speeds of the pump, but a tight bearing will overheat and the babbitt may melt or pull. with experience, an operator can tell by feel when the bearings are properly adjusted. Normal precautions must be taken to insure cleanliness of parts upon their assembly. All wrenches used in adjusting these bearings are standard wrenches.

The Liberty Process LL8 Progressive Cavity Pump is ideal for abrasive pumping applications such as drilling fluids with sand and grit common in fracking operations. As a Mud Pump, the LL8 Series is a popular model on many mobile pumping rigs in use today. Replacement mud pump parts are available as well from our stock and work on other popular manufacturers models.

LL8 parts are direct drop in aftermarket replacements that work with the *Moyno® L8 series, the *Tarby® TL8 series and *Continental® CL8 Series*. The Liberty unit is a low-cost, maintenance free, dependable drop-in replacement progressive cavity unit.

The Liberty LL8 is a standard flanged pump design manufactured with cast iron or 316 stainless steel pump casings designed in 1, 2, and 3 stages for 75, 150 and 225 psi discharge pressures and a flow rate of 18 up to 100 GPM.

The LL8 is a modular design with simple hardened pinned joint drive assembly. LL8 Rotors are typically hardened tool steel or 316 stainless steel with a hard chrome plating for long life in abrasive pumping applications.

All other wetted parts are either carbon steel or 316 stainless steel. Stators are available in many elastomer materials such as Buna Nitrile, Natural Rubber, EPDM and Viton. The standard seal design is a set of gland packing with a lantern ring set and flush connections. Mechanical seal options for this progressive cavity pump are readily available.

The LL8 represents one of the most popular progressive cavity pumps available for the transport of drilling mud with easily replaceable in-stock parts.

Mechanical pumps serve in a wide range of applications such as pumping water from wells, aquarium filtering, pond filtering and aeration, in the car industry for water-cooling and fuel injection, in the energy industry for pumping oil and natural gas or for operating cooling towers and other components of heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems. In the medical industry, pumps are used for biochemical processes in developing and manufacturing medicine, and as artificial replacements for body parts, in particular the artificial heart and penile prosthesis.

When a pump contains two or more pump mechanisms with fluid being directed to flow through them in series, it is called a multi-stage pump. Terms such as two-stage or double-stage may be used to specifically describe the number of stages. A pump that does not fit this description is simply a single-stage pump in contrast.

In biology, many different types of chemical and biomechanical pumps have evolved; biomimicry is sometimes used in developing new types of mechanical pumps.

Pumps can be classified by their method of displacement into positive-displacement pumps, impulse pumps, velocity pumps, gravity pumps, steam pumps and valveless pumps. There are three basic types of pumps: positive-displacement, centrifugal and axial-flow pumps. In centrifugal pumps the direction of flow of the fluid changes by ninety degrees as it flows over an impeller, while in axial flow pumps the direction of flow is unchanged.

Some positive-displacement pumps use an expanding cavity on the suction side and a decreasing cavity on the discharge side. Liquid flows into the pump as the cavity on the suction side expands and the liquid flows out of the discharge as the cavity collapses. The volume is constant through each cycle of operation.

Positive-displacement pumps, unlike centrifugal, can theoretically produce the same flow at a given speed (rpm) no matter what the discharge pressure. Thus, positive-displacement pumps are constant flow machines. However, a slight increase in internal leakage as the pressure increases prevents a truly constant flow rate.

A positive-displacement pump must not operate against a closed valve on the discharge side of the pump, because it has no shutoff head like centrifugal pumps. A positive-displacement pump operating against a closed discharge valve continues to produce flow and the pressure in the discharge line increases until the line bursts, the pump is severely damaged, or both.

A relief or safety valve on the discharge side of the positive-displacement pump is therefore necessary. The relief valve can be internal or external. The pump manufacturer normally has the option to supply internal relief or safety valves. The internal valve is usually used only as a safety precaution. An external relief valve in the discharge line, with a return line back to the suction line or supply tank provides increased safety.

Rotary-type positive displacement: internal or external gear pump, screw pump, lobe pump, shuttle block, flexible vane or sliding vane, circumferential piston, flexible impeller, helical twisted roots (e.g. the Wendelkolben pump) or liquid-ring pumps

Drawbacks: The nature of the pump requires very close clearances between the rotating pump and the outer edge, making it rotate at a slow, steady speed. If rotary pumps are operated at high speeds, the fluids cause erosion, which eventually causes enlarged clearances that liquid can pass through, which reduces efficiency.

Hollow disk pumps (also known as eccentric disc pumps or Hollow rotary disc pumps), similar to scroll compressors, these have a cylindrical rotor encased in a circular housing. As the rotor orbits and rotates to some degree, it traps fluid between the rotor and the casing, drawing the fluid through the pump. It is used for highly viscous fluids like petroleum-derived products, and it can also support high pressures of up to 290 psi.

Vibratory pumps or vibration pumps are similar to linear compressors, having the same operating principle. They work by using a spring-loaded piston with an electromagnet connected to AC current through a diode. The spring-loaded piston is the only moving part, and it is placed in the center of the electromagnet. During the positive cycle of the AC current, the diode allows energy to pass through the electromagnet, generating a magnetic field that moves the piston backwards, compressing the spring, and generating suction. During the negative cycle of the AC current, the diode blocks current flow to the electromagnet, letting the spring uncompress, moving the piston forward, and pumping the fluid and generating pressure, like a reciprocating pump. Due to its low cost, it is widely used in inexpensive espresso machines. However, vibratory pumps cannot be operated for more than one minute, as they generate large amounts of heat. Linear compressors do not have this problem, as they can be cooled by the working fluid (which is often a refrigerant).

Reciprocating pumps move the fluid using one or more oscillating pistons, plungers, or membranes (diaphragms), while valves restrict fluid motion to the desired direction. In order for suction to take place, the pump must first pull the plunger in an outward motion to decrease pressure in the chamber. Once the plunger pushes back, it will increase the chamber pressure and the inward pressure of the plunger will then open the discharge valve and release the fluid into the delivery pipe at constant flow rate and increased pressure.

Pumps in this category range from simplex, with one cylinder, to in some cases quad (four) cylinders, or more. Many reciprocating-type pumps are duplex (two) or triplex (three) cylinder. They can be either single-acting with suction during one direction of piston motion and discharge on the other, or double-acting with suction and discharge in both directions. The pumps can be powered manually, by air or steam, or by a belt driven by an engine. This type of pump was used extensively in the 19th century—in the early days of steam propulsion—as boiler feed water pumps. Now reciprocating pumps typically pump highly viscous fluids like concrete and heavy oils, and serve in special applications that demand low flow rates against high resistance. Reciprocating hand pumps were widely used to pump water from wells. Common bicycle pumps and foot pumps for inflation use reciprocating action.

These positive-displacement pumps have an expanding cavity on the suction side and a decreasing cavity on the discharge side. Liquid flows into the pumps as the cavity on the suction side expands and the liquid flows out of the discharge as the cavity collapses. The volume is constant given each cycle of operation and the pump"s volumetric efficiency can be achieved through routine maintenance and inspection of its valves.

This is the simplest form of rotary positive-displacement pumps. It consists of two meshed gears that rotate in a closely fitted casing. The tooth spaces trap fluid and force it around the outer periphery. The fluid does not travel back on the meshed part, because the teeth mesh closely in the center. Gear pumps see wide use in car engine oil pumps and in various hydraulic power packs.

A screw pump is a more complicated type of rotary pump that uses two or three screws with opposing thread — e.g., one screw turns clockwise and the other counterclockwise. The screws are mounted on parallel shafts that have gears that mesh so the shafts turn together and everything stays in place. The screws turn on the shafts and drive fluid through the pump. As with other forms of rotary pumps, the clearance between moving parts and the pump"s casing is minimal.

Widely used for pumping difficult materials, such as sewage sludge contaminated with large particles, a progressing cavity pump consists of a helical rotor, about ten times as long as its width. This can be visualized as a central core of diameter x with, typically, a curved spiral wound around of thickness half x, though in reality it is manufactured in a single casting. This shaft fits inside a heavy-duty rubber sleeve, of wall thickness also typically x. As the shaft rotates, the rotor gradually forces fluid up the rubber sleeve. Such pumps can develop very high pressure at low volumes.

Named after the Roots brothers who invented it, this lobe pump displaces the fluid trapped between two long helical rotors, each fitted into the other when perpendicular at 90°, rotating inside a triangular shaped sealing line configuration, both at the point of suction and at the point of discharge. This design produces a continuous flow with equal volume and no vortex. It can work at low pulsation rates, and offers gentle performance that some applications require.

A peristaltic pump is a type of positive-displacement pump. It contains fluid within a flexible tube fitted inside a circular pump casing (though linear peristaltic pumps have been made). A number of rollers, shoes, or wipers attached to a rotor compresses the flexible tube. As the rotor turns, the part of the tube under compression closes (or occludes), forcing the fluid through the tube. Additionally, when the tube opens to its natural state after the passing of the cam it draws (restitution) fluid into the pump. This process is called peristalsis and is used in many biological systems such as the gastrointestinal tract.

Efficiency and common problems: With only one cylinder in plunger pumps, the fluid flow varies between maximum flow when the plunger moves through the middle positions, and zero flow when the plunger is at the end positions. A lot of energy is wasted when the fluid is accelerated in the piping system. Vibration and

Triplex plunger pumps use three plungers, which reduces the pulsation of single reciprocating plunger pumps. Adding a pulsation dampener on the pump outlet can further smooth the pump ripple, or ripple graph of a pump transducer. The dynamic relationship of the high-pressure fluid and plunger generally requires high-quality plunger seals. Plunger pumps with a larger number of plungers have the benefit of increased flow, or smoother flow without a pulsation damper. The increase in moving parts and crankshaft load is one drawback.

Car washes often use these triplex-style plunger pumps (perhaps without pulsation dampers). In 1968, William Bruggeman reduced the size of the triplex pump and increased the lifespan so that car washes could use equipment with smaller footprints. Durable high-pressure seals, low-pressure seals and oil seals, hardened crankshafts, hardened connecting rods, thick ceramic plungers and heavier duty ball and roller bearings improve reliability in triplex pumps. Triplex pumps now are in a myriad of markets across the world.

Triplex pumps with shorter lifetimes are commonplace to the home user. A person who uses a home pressure washer for 10 hours a year may be satisfied with a pump that lasts 100 hours between rebuilds. Industrial-grade or continuous duty triplex pumps on the other end of the quality spectrum may run for as much as 2,080 hours a year.

The oil and gas drilling industry uses massive semi trailer-transported triplex pumps called mud pumps to pump drilling mud, which cools the drill bit and carries the cuttings back to the surface.

One modern application of positive-displacement pumps is compressed-air-powered double-diaphragm pumps. Run on compressed air, these pumps are intrinsically safe by design, although all manufacturers offer ATEX certified models to comply with industry regulation. These pumps are relatively inexpensive and can perform a wide variety of duties, from pumping water out of bunds to pumping hydrochloric acid from secure storage (dependent on how the pump is manufactured – elastomers / body construction). These double-diaphragm pumps can handle viscous fluids and abrasive materials with a gentle pumping process ideal for transporting shear-sensitive media.

Devised in China as chain pumps over 1000 years ago, these pumps can be made from very simple materials: A rope, a wheel and a pipe are sufficient to make a simple rope pump. Rope pump efficiency has been studied by grassroots organizations and the techniques for making and running them have been continuously improved.

Impulse pumps use pressure created by gas (usually air). In some impulse pumps the gas trapped in the liquid (usually water), is released and accumulated somewhere in the pump, creating a pressure that can push part of the liquid upwards.

Instead of a gas accumulation and releasing cycle, the pressure can be created by burning of hydrocarbons. Such combustion driven pumps directly transmit the impulse from a combustion event through the actuation membrane to the pump fluid. In order to allow this direct transmission, the pump needs to be almost entirely made of an elastomer (e.g. silicone rubber). Hence, the combustion causes the membrane to expand and thereby pumps the fluid out of the adjacent pumping chamber. The first combustion-driven soft pump was developed by ETH Zurich.

It takes in water at relatively low pressure and high flow-rate and outputs water at a higher hydraulic-head and lower flow-rate. The device uses the water hammer effect to develop pressure that lifts a portion of the input water that powers the pump to a point higher than where the water started.

The hydraulic ram is sometimes used in remote areas, where there is both a source of low-head hydropower, and a need for pumping water to a destination higher in elevation than the source. In this situation, the ram is often useful, since it requires no outside source of power other than the kinetic energy of flowing water.

Rotodynamic pumps (or dynamic pumps) are a type of velocity pump in which kinetic energy is added to the fluid by increasing the flow velocity. This increase in energy is converted to a gain in potential energy (pressure) when the velocity is reduced prior to or as the flow exits the pump into the discharge pipe. This conversion of kinetic energy to pressure is explained by the

A practical difference between dynamic and positive-displacement pumps is how they operate under closed valve conditions. Positive-displacement pumps physically displace fluid, so closing a valve downstream of a positive-displacement pump produces a continual pressure build up that can cause mechanical failure of pipeline or pump. Dynamic pumps differ in that they can be safely operated under closed valve conditions (for short periods of time).

Such a pump is also referred to as a centrifugal pump. The fluid enters along the axis or center, is accelerated by the impeller and exits at right angles to the shaft (radially); an example is the centrifugal fan, which is commonly used to implement a vacuum cleaner. Another type of radial-flow pump is a vortex pump. The liquid in them moves in tangential direction around the working wheel. The conversion from the mechanical energy of motor into the potential energy of flow comes by means of multiple whirls, which are excited by the impeller in the working channel of the pump. Generally, a radial-flow pump operates at higher pressures and lower flow rates than an axial- or a mixed-flow pump.

These are also referred to as All fluid pumps. The fluid is pushed outward or inward to move fluid axially. They operate at much lower pressures and higher flow rates than radial-flow (centrifugal) pumps. Axial-flow pumps cannot be run up to speed without special precaution. If at a low flow rate, the total head rise and high torque associated with this pipe would mean that the starting torque would have to become a function of acceleration for the whole mass of liquid in the pipe system. If there is a large amount of fluid in the system, accelerate the pump slowly.

Mixed-flow pumps function as a compromise between radial and axial-flow pumps. The fluid experiences both radial acceleration and lift and exits the impeller somewhere between 0 and 90 degrees from the axial direction. As a consequence mixed-flow pumps operate at higher pressures than axial-flow pumps while delivering higher discharges than radial-flow pumps. The exit angle of the flow dictates the pressure head-discharge characteristic in relation to radial and mixed-flow.

Regenerative turbine pump rotor and housing, 1⁄3 horsepower (0.25 kW). 85 millimetres (3.3 in) diameter impeller rotates counter-clockwise. Left: inlet, right: outlet. .4 millimetres (0.016 in) thick vanes on 4 millimetres (0.16 in) centers

Also known as drag, friction, peripheral, traction, turbulence, or vortex pumps, regenerative turbine pumps are class of rotodynamic pump that operates at high head pressures, typically 4–20 bars (4.1–20.4 kgf/cm2; 58–290 psi).

The pump has an impeller with a number of vanes or paddles which spins in a cavity. The suction port and pressure ports are located at the perimeter of the cavity and are isolated by a barrier called a stripper, which allows only the tip channel (fluid between the blades) to recirculate, and forces any fluid in the side channel (fluid in the cavity outside of the blades) through the pressure port. In a regenerative turbine pump, as fluid spirals repeatedly from a vane into the side channel and back to the next vane, kinetic energy is imparted to the periphery,

As regenerative turbine pumps cannot become vapor locked, they are commonly applied to volatile, hot, or cryogenic fluid transport. However, as tolerances are typically tight, they are vulnerable to solids or particles causing jamming or rapid wear. Efficiency is typically low, and pressure and power consumption typically decrease with flow. Additionally, pumping direction can be reversed by reversing direction of spin.

Steam pumps have been for a long time mainly of historical interest. They include any type of pump powered by a steam engine and also pistonless pumps such as Thomas Savery"s or the Pulsometer steam pump.

Recently there has been a resurgence of interest in low power solar steam pumps for use in smallholder irrigation in developing countries. Previously small steam engines have not been viable because of escalating inefficiencies as vapour engines decrease in size. However the use of modern engineering materials coupled with alternative engine configurations has meant that these types of system are now a cost-effective opportunity.

Valveless pumping assists in fluid transport in various biomedical and engineering systems. In a valveless pumping system, no valves (or physical occlusions) are present to regulate the flow direction. The fluid pumping efficiency of a valveless system, however, is not necessarily lower than that having valves. In fact, many fluid-dynamical systems in nature and engineering more or less rely upon valveless pumping to transport the working fluids therein. For instance, blood circulation in the cardiovascular system is maintained to some extent even when the heart"s valves fail. Meanwhile, the embryonic vertebrate heart begins pumping blood long before the development of discernible chambers and valves. Similar to blood circulation in one direction, bird respiratory systems pump air in one direction in rigid lungs, but without any physiological valve. In microfluidics, valveless impedance pumps have been fabricated, and are expected to be particularly suitable for handling sensitive biofluids. Ink jet printers operating on the piezoelectric transducer principle also use valveless pumping. The pump chamber is emptied through the printing jet due to reduced flow impedance in that direction and refilled by capillary action.

Examining pump repair records and mean time between failures (MTBF) is of great importance to responsible and conscientious pump users. In view of that fact, the preface to the 2006 Pump User"s Handbook alludes to "pump failure" statistics. For the sake of convenience, these failure statistics often are translated into MTBF (in this case, installed life before failure).

In early 2005, Gordon Buck, John Crane Inc.’s chief engineer for field operations in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, examined the repair records for a number of refinery and chemical plants to obtain meaningful reliability data for centrifugal pumps. A total of 15 operating plants having nearly 15,000 pumps were included in the survey. The smallest of these plants had about 100 pumps; several plants had over 2000. All facilities were located in the United States. In addition, considered as "new", others as "renewed" and still others as "established". Many of these plants—but not all—had an alliance arrangement with John Crane. In some cases, the alliance contract included having a John Crane Inc. technician or engineer on-site to coordinate various aspects of the program.

Not all plants are refineries, however, and different results occur elsewhere. In chemical plants, pumps have historically been "throw-away" items as chemical attack limits life. Things have improved in recent years, but the somewhat restricted space available in "old" DIN and ASME-standardized stuffing boxes places limits on the type of seal that fits. Unless the pump user upgrades the seal chamber, the pump only accommodates more compact and simple versions. Without this upgrading, lifetimes in chemical installations are generally around 50 to 60 percent of the refinery values.

Unscheduled maintenance is often one of the most significant costs of ownership, and failures of mechanical seals and bearings are among the major causes. Keep in mind the potential value of selecting pumps that cost more initially, but last much longer between repairs. The MTBF of a better pump may be one to four years longer than that of its non-upgraded counterpart. Consider that published average values of avoided pump failures range from US$2600 to US$12,000. This does not include lost opportunity costs. One pump fire occurs per 1000 failures. Having fewer pump failures means having fewer destructive pump fires.

As has been noted, a typical pump failure, based on actual year 2002 reports, costs US$5,000 on average. This includes costs for material, parts, labor and overhead. Extending a pump"s MTBF from 12 to 18 months would save US$1,667 per year — which might be greater than the cost to upgrade the centrifugal pump"s reliability.

Pumps are used throughout society for a variety of purposes. Early applications includes the use of the windmill or watermill to pump water. Today, the pump is used for irrigation, water supply, gasoline supply, air conditioning systems, refrigeration (usually called a compressor), chemical movement, sewage movement, flood control, marine services, etc.

Because of the wide variety of applications, pumps have a plethora of shapes and sizes: from very large to very small, from handling gas to handling liquid, from high pressure to low pressure, and from high volume to low volume.

Typically, a liquid pump can"t simply draw air. The feed line of the pump and the internal body surrounding the pumping mechanism must first be filled with the liquid that requires pumping: An operator must introduce liquid into the system to initiate the pumping. This is called priming the pump. Loss of prime is usually due to ingestion of air into the pump. The clearances and displacement ratios in pumps for liquids, whether thin or more viscous, usually cannot displace air due to its compressibility. This is the case with most velocity (rotodynamic) pumps — for example, centrifugal pumps. For such pumps, the position of the pump should always be lower than the suction point, if not the pump should be manually filled with liquid or a secondary pump should be used until all air is removed from the suction line and the pump casing.

Positive–displacement pumps, however, tend to have sufficiently tight sealing between the moving parts and the casing or housing of the pump that they can be described as self-priming. Such pumps can also serve as priming pumps, so-called when they are used to fulfill that need for other pumps in lieu of action taken by a human operator.

One sort of pump once common worldwide was a hand-powered water pump, or "pitcher pump". It was commonly installed over community water wells in the days before piped water supplies.

In parts of the British Isles, it was often called the parish pump. Though such community pumps are no longer common, people still used the expression parish pump to describe a place or forum where matters of local interest are discussed.

Because water from pitcher pumps is drawn directly from the soil, it is more prone to contamination. If such water is not filtered and purified, consumption of it might lead to gastrointestinal or other water-borne diseases. A notorious case is the 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak. At the time it was not known how cholera was transmitted, but physician John Snow suspected contaminated water and had the handle of the public pump he suspected removed; the outbreak then subsided.

Modern hand-operated community pumps are considered the most sustainable low-cost option for safe water supply in resource-poor settings, often in rural areas in developing countries. A hand pump opens access to deeper groundwater that is often not polluted and also improves the safety of a well by protecting the water source from contaminated buckets. Pumps such as the Afridev pump are designed to be cheap to build and install, and easy to maintain with simple parts. However, scarcity of spare parts for these type of pumps in some regions of Africa has diminished their utility for these areas.

Multiphase pumping applications, also referred to as tri-phase, have grown due to increased oil drilling activity. In addition, the economics of multiphase production is attractive to upstream operations as it leads to simpler, smaller in-field installations, reduced equipment costs and improved production rates. In essence, the multiphase pump can accommodate all fluid stream properties with one piece of equipment, which has a smaller footprint. Often, two smaller multiphase pumps are installed in series rather than having just one massive pump.

A rotodynamic pump with one single shaft that requires two mechanical seals, this pump uses an open-type axial impeller. It is often called a Poseidon pump, and can be described as a cross between an axial compressor and a centrifugal pump.

The twin-screw pump is constructed of two inter-meshing screws that move the pumped fluid. Twin screw pumps are often used when pumping conditions contain high gas volume fractions and fluctuating inlet conditions. Four mechanical seals are required to seal the two shafts.

These pumps are basically multistage centrifugal pumps and are widely used in oil well applications as a method for artificial lift. These pumps are usually specified when the pumped fluid is mainly liquid.

A buffer tank is often installed upstream of the pump suction nozzle in case of a slug flow. The buffer tank breaks the energy of the liquid slug, smooths any fluctuations in the incoming flow and acts as a sand trap.

As the name indicates, multiphase pumps and their mechanical seals can encounter a large variation in service conditions such as changing process fluid composition, temperature variations, high and low operating pressures and exposure to abrasive/erosive media. The challenge is selecting the appropriate mechanical seal arrangement and support system to ensure maximized seal life and its overall effectiveness.

Pumps are commonly rated by horsepower, volumetric flow rate, outlet pressure in metres (or feet) of head, inlet suction in suction feet (or metres) of head.

From an initial design point of view, engineers often use a quantity termed the specific speed to identify the most suitable pump type for a particular combination of flow rate and head.

The power imparted into a fluid increases the energy of the fluid per unit volume. Thus the power relationship is between the conversion of the mechanical energy of the pump mechanism and the fluid elements within the pump. In general, this is governed by a series of simultaneous differential equations, known as the Navier–Stokes equations. However a more simple equation relating only the different energies in the fluid, known as Bernoulli"s equation can be used. Hence the power, P, required by the pump:

where Δp is the change in total pressure between the inlet and outlet (in Pa), and Q, the volume flow-rate of the fluid is given in m3/s. The total pressure may have gravitational, static pressure and kinetic energy components; i.e. energy is distributed between change in the fluid"s gravitational potential energy (going up or down hill), change in velocity, or change in static pressure. η is the pump efficiency, and may be given by the manufacturer"s information, such as in the form of a pump curve, and is typically derived from either fluid dynamics simulation (i.e. solutions to the Navier–Stokes for the particular pump geometry), or by testing. The efficiency of the pump depends upon the pump"s configuration and operating conditions (such as rotational speed, fluid density and viscosity etc.)

For a typical "pumping" configuration, the work is imparted on the fluid, and is thus positive. For the fluid imparting the work on the pump (i.e. a turbine), the work is negative. Power required to drive the pump is determined by dividing the output power by the pump efficiency. Furthermore, this definition encompasses pumps with no moving parts, such as a siphon.

Pump efficiency is defined as the ratio of the power imparted on the fluid by the pump in relation to the power supplied to drive the pump. Its value is not fixed for a given pump, efficiency is a function of the discharge and therefore also operating head. For centrifugal pumps, the efficiency tends to increase with flow rate up to a point midway through the operating range (peak efficiency or Best Efficiency Point (BEP) ) and then declines as flow rates rise further. Pump performance data such as this is usually supplied by the manufacturer before pump selection. Pump efficiencies tend to decline over time due to wear (e.g. increasing clearances as impellers reduce in size).

When a system includes a centrifugal pump, an important design issue is matching the head loss-flow characteristic with the pump so that it operates at or close to the point of its maximum efficiency.

Most large pumps have a minimum flow requirement below which the pump may be damaged by overheating, impeller wear, vibration, seal failure, drive shaft damage or poor performance.

The simplest minimum flow system is a pipe running from the pump discharge line back to the suction line. This line is fitted with an orifice plate sized to allow the pump minimum flow to pass.

A more sophisticated, but more costly, system (see diagram) comprises a flow measuring device (FE) in the pump discharge which provides a signal into a flow controller (FIC) which actuates a flow control valve (FCV) in the recycle line. If the measured flow exceeds the minimum flow then the FCV is closed. If the measured flow falls below the minimum flow the FCV opens to maintain the minimum flowrate.

As the fluids are recycled the kinetic energy of the pump increases the temperature of the fluid. For many pumps this added heat energy is dissipated through the pipework. However, for large industrial pumps, such as oil pipeline pumps, a recycle cooler is provided in the recycle line to cool the fluids to the normal suction temperature.oil refinery, oil terminal, or offshore installation.

Engineering Sciences Data Unit (2007). "Radial, mixed and axial flow pumps. Introduction" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-08. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

Tanzania water Archived 2012-03-31 at the Wayback Machine blog – example of grassroots researcher telling about his study and work with the rope pump in Africa.

C.M. Schumacher, M. Loepfe, R. Fuhrer, R.N. Grass, and W.J. Stark, "3D printed lost-wax casted soft silicone monoblocks enable heart-inspired pumping by internal combustion," RSC Advances, Vol. 4, pp. 16039–16042, 2014.

"Radial, mixed and axial flow pumps" (PDF). Institution of Diploma Marine Engineers, Bangladesh. June 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-08. Retrieved 2017-08-18.

Quail F, Scanlon T, Stickland M (2011-01-11). "Design optimisation of a regenerative pump using numerical and experimental techniques" (PDF). International Journal of Numerical Methods for Heat & Fluid Flow. 21: 95–111. doi:10.1108/09615531111095094. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

Rajmane, M. Satish; Kallurkar, S.P. (May 2015). "CFD Analysis of Domestic Centrifugal Pump for Performance Enhancement". International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology. 02 / #02. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

Wasser, Goodenberger, Jim and Bob (November 1993). "Extended Life, Zero Emissions Seal for Process Pumps". John Crane Technical Report. Routledge. TRP 28017.

Australian Pump Manufacturers" Association. Australian Pump Technical Handbook, 3rd edition. Canberra: Australian Pump Manufacturers" Association, 1987. ISBN 0-7316-7043-4.

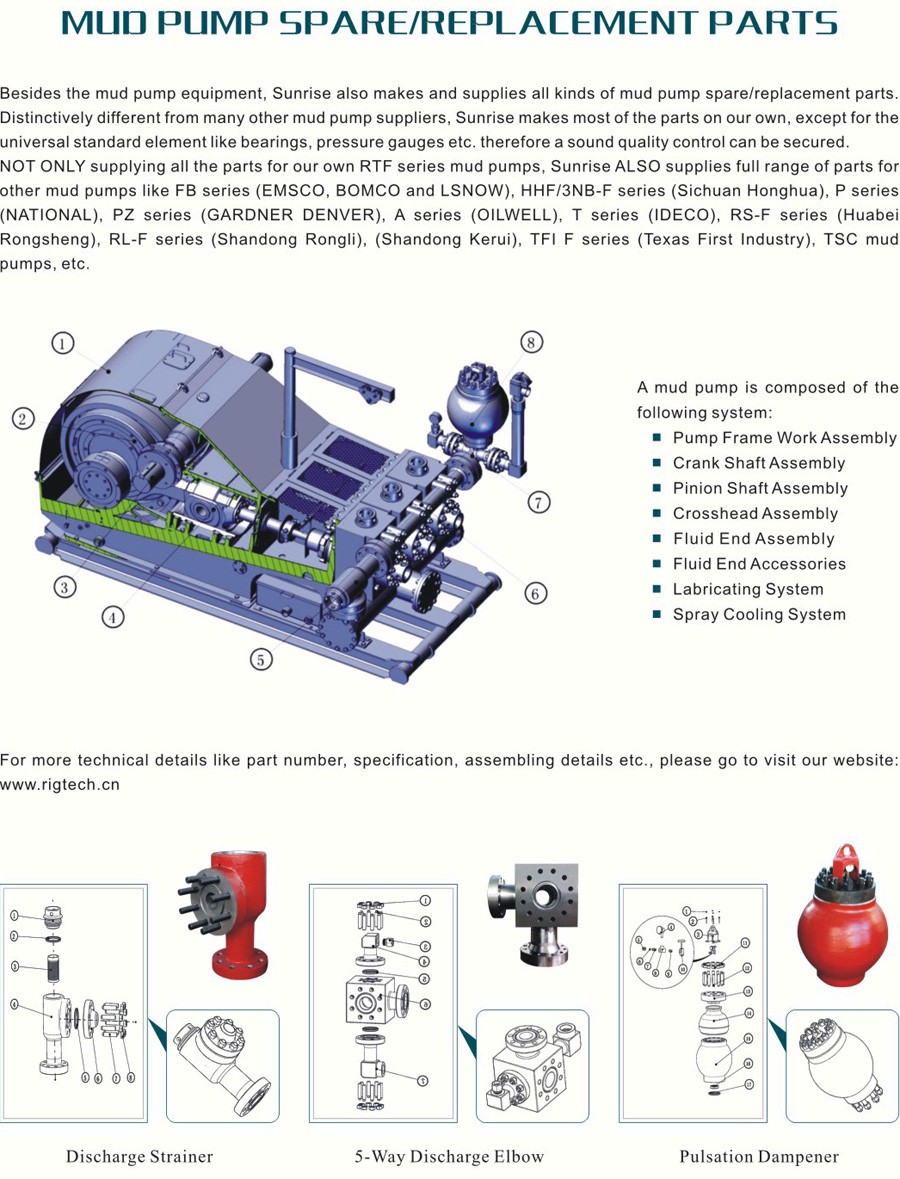

The mud pumps market size is expected to grow at a significant rate during the forecast period. A mud pump is a large, high-pressure (up to 7500 psi), single-acting triplex reciprocating pump used to circulate mud in a well at a specific flow rate (between 100 and 1300 gallons per minute). Instead of a triplex reciprocating pump, a double-acting two-cylinder reciprocating pump is occasionally utilized as a mud pump. Typically, a rig operator keeps two or three mud pumps on hand, one of which is active and the others on standby in case of an emergency. Mud is gathered up with the use of mud pumps, which use suction to circulate the mud from the wellbore to the surface during the drilling process.

Increased demand for directional and horizontal drilling, higher pressure handling capabilities, and some new oil discoveries are the main drivers of this market"s growth. Mud pumps are specialized pumps that are used to transport and circulate drilling fluids and other related fluids in a variety of industries, including mining and onshore and offshore oil and gas. The global energy demand is boosting the market for mud pumps. However, high drilling costs, environmental concerns, and shifting government energy and power laws may stymie industry growth.

Innovation in technology is the key for further growth for example, MTeq uses Energy Recovery’s Pressure exchanger technology in the drilling industry, as the ultimate engineered solution to increase productivity and reduce operating costs in pumping process by rerouting rough fluids away from high-pressure pumps, which helps reduce the cost of maintenance for operators.

The major key player in global mud pumps market are Flowserve (U.S.), Grundfos (Denmark), Halliburton (U.S.), Sulzer (Switzerland), KSB Group (Germany), Ebara Corporation (Japan), Weir Group (U.K), and SRS Crisafulli, Inc (U.S.). Tsurumi Pump (Japan), Shijiazhuang Industrial Pump Factory Co. Ltd (China), Excellence Pump Industry Co.Ltd (China), Kirloskar Ebara Pumps Limited (India), Xylem Inc (U.S.), and Goulds Pumps (U.S.) are among others.

In the drilling business, MTeq uses Energy Recovery"s Pressure exchanger technology as the ultimate engineering solution to boost productivity and lower operating costs in the pumping process by rerouting abrasive fluids away from high-pressure pumps, which helps operators save money on maintenance. The latest trend reveals that regulatory agencies are persuading manufacturers and consumers to choose electric mud pumps over fuel engine mu

8613371530291

8613371530291