mud pump piston failure free sample

Cavitation is an undesirable condition that reduces pump efficiency and leads to excessive wear and damage to pump components. Factors that can contribute to cavitation, such as fluid velocity and pressure, can sometimes be attributed to an inadequate mud system design and/or the diminishing performance of the mud pump’s feed system.

Although cavitation is avoidable, without proper inspection of the feed system, it can accelerate the wear of fluid end parts. Over time, cavitation can also lead to expensive maintenance issues and a potentially catastrophic failure.

When a mud pump has entered full cavitation, rig crews and field service technicians will see the equipment shaking and hear the pump “knocking,” which typically sounds like marbles and stones being thrown around inside the equipment. However, the process of cavitation starts long before audible signs reveal themselves – hence the name “the silent killer.”

Mild cavitation begins to occur when the mud pump is starved for fluid. While the pump itself may not be making noise, damage is still being done to the internal components of the fluid end. In the early stages, cavitation can damage a pump’s module, piston and valve assembly.

The imperceptible but intense shock waves generated by cavitation travel directly from the fluid end to the pump’s power end, causing premature vibrational damage to the crosshead slides. The vibrations are then passed onto the shaft, bull gear and into the main bearings.

If not corrected, the vibrations caused by cavitation will work their way directly to critical power end components, which will result in the premature failure of the mud pump. A busted mud pump means expensive downtime and repair costs.

Washouts are one of the leading causes of module failure and take place when the high-pressure fluid cuts through the module’s surface and damages a sealing surface. These unexpected failures are expensive and can lead to a minimum of eight hours of rig downtime for module replacement.

To stop cavitation before it starts, install and tune high-speed pressure sensors on the mud suction line set to sound an alarm if the pressure falls below 30 psi.

Although the pump may not be knocking loudly when cavitation first presents, regular inspections by a properly trained field technician may be able to detect moderate vibrations and slight knocking sounds.

Gardner Denver offers Pump University, a mobile classroom that travels to facilities and/or drilling rigs and trains rig crews on best practices for pumping equipment maintenance.

Severe cavitation will drastically decrease module life and will eventually lead to catastrophic pump failure. Along with downtime and repair costs, the failure of the drilling pump can also cause damage to the suction and discharge piping.

When a mud pump has entered full cavitation, rig crews and field service technicians will see the equipment shaking and hear the pump ‘knocking’… However, the process of cavitation starts long before audible signs reveal themselves – hence the name ‘the silent killer.’In 2017, a leading North American drilling contractor was encountering chronic mud system issues on multiple rigs. The contractor engaged in more than 25 premature module washes in one year and suffered a major power-end failure.

Gardner Denver’s engineering team spent time on the contractor’s rigs, observing the pumps during operation and surveying the mud system’s design and configuration.

The engineering team discovered that the suction systems were undersized, feed lines were too small and there was no dampening on the suction side of the pump.

Following the implementation of these recommendations, the contractor saw significant performance improvements from the drilling pumps. Consumables life was extended significantly, and module washes were reduced by nearly 85%.

Although pump age does not affect its susceptibility to cavitation, the age of the rig can. An older rig’s mud systems may not be equipped for the way pumps are run today – at maximum horsepower.

abstractNote = {Failure of a liner seal is one of the more critical failures on a mud pump because this seal interfaces with the pump body. Therefore, failures, usually damage the pump body, leading to repair or replacement of the fluid end itself. One of the more common liner seal problems involves counter-bore-type seals. This type of seal is easily affected by two aspects of the problem that are found in the mud pump fluid end-wear and foreign matter in the seal groove. Factors relative to difficult liner removal are discussed. Piston damage, careless seal installation and corrosion damage are also examined.},

As usual, winter — or the slow season — is the time most drillers take the time to maintain their equipment in order to get ready for the peak season. One of the main parts that usually needs attention is the mud pump. Sometimes, it is just a set of swabs to bring it up to snuff, but often, tearing it down and inspecting the parts may reveal that other things need attention. For instance, liners. I can usually run three sets of swabs before it is time to change the liner. New liners and swabs last a good long time. The second set of swabs lasts less, and by the time you put in your third set of swabs, it’s time to order new liners. Probably rods too. It’s not always necessary to change pistons when you change swabs. Sometimes just the rubber needs to be changed, saving money. How do you tell? There is a small groove around the outside of the piston. As it wears, the groove will disappear and it’s time for a new piston.

The wear groove on a piston can be a good indicator of the general health of your pump. If the wear is pretty even all around, chances are the pump is in pretty good shape. But if you see wear on one side only, that is a clue to dig deeper. Uneven wear is a sign that the rods are not stroking at the exact angle that they were designed to, which is parallel to the liner. So, it’s time to look at the gear end. Or as some folks call it, “the expensive end.”

The wear groove on a piston can be a good indicator of the general health of your pump. If the wear is pretty even all around, chances are the pump is in pretty good shape. But if you see wear on one side only, that is a clue to dig deeper.

After you get the cover off the gear end, the first thing to look at will be the oil. It needs to be fairly clean, with no drill mud in it. Also look for metal. Some brass is to be expected, but if you put a magnet in the oil and come back later and it has more than a little metal on it, it gets more serious. The brass in the big end of the connecting rod is a wearable part. It is made to be replaced at intervals — usually years. The most common source of metal is from the bull and pinion gears. They transmit the power to the mud. If you look at the pinion gear closely, you will find that it wears faster than the bull gear. This is for two reasons. First, it is at the top of the pump and may not receive adequate lubrication. The second reason is wear. All the teeth on both the bull and pinion gears receive the same amount of wear, but the bull gear has many more teeth to spread the wear. That is why, with a well maintained pump, the bull gear will outlast the pinion gear three, four or even five times. Pinion gears aren’t too expensive and are fairly easy to change.

This process is fairly straightforward machine work, but over the years, I have discovered a trick that will bring a rebuild up to “better than new.” When you tear a pump down, did you ever notice that there is about 1-inch of liner on each end that has no wear? This is because the swab never gets to it. If it has wear closer to one end than the other, your rods are out of adjustment. The trick is to offset grind the journals. I usually offset mine about ¼-inch. This gives me a ½-inch increase in the stroke without weakening the gear end. This turns a 5x6 pump into a 5½x6 pump. More fluid equals better holes. I adjust the rods to the right length to keep from running out the end of the liner, and enjoy the benefits.

Other than age, the problem I have seen with journal wear is improper lubrication. Smaller pumps rely on splash lubrication. This means that as the crank strokes, the rods pick up oil and it lubricates the crank journals. If your gear end is full of drill mud due to bad packing, it’s going to eat your pump. If the oil is clean, but still shows crank wear, you need to look at the oil you are using.

Oil that is too thick will not be very well picked up and won’t find its way into the oil holes in the brass to lubricate the journals. I’ve seen drillers that, when their pump starts knocking, they switch to a heavier weight oil. This actually makes the problem worse. In my experience, factory specified gear end oil is designed for warmer climates. As you move north, it needs to be lighter to do its job. Several drillers I know in the Northern Tier and Canada run 30 weight in their pumps. In Georgia, I run 40W90. Seems to work well.

This rig features a Mission 4-by-5 centrifugal pump. Courtesy of Higgins Rig Co.Returning to the water well industry when I joined Schramm Inc. last year, I knew that expanding my mud pump knowledge was necessary to represent the company"s mud rotary drill line properly. One item new to me was the centrifugal mud pump. What was this pump that a number of drillers were using? I had been trained that a piston pump was the only pump of any ability.

As I traveled and questioned drillers, I found that opinions of the centrifugal pumps varied. "Best pump ever built," "What a piece of junk" and "Can"t drill more than 200 feet with a centrifugal" were typical of varying responses. Because different opinions had confused the issue, I concluded my discussions and restarted my education with a call to a centrifugal pump manufacturer. After that conversation, I went back to the field to continue my investigation.

For the past eight months, I have held many discussions and conducted field visits to understand the centrifugal pump. As a result, my factual investigation has clearly proved that the centrifugal pump has a place in mud rotary drilling. The fact also is clear that many drilling contractors do not understand the correct operational use of the pump. Following are the results of my work in the field.

High up-hole velocity - High pump flow (gpm) moves cuttings fast. This works well with lower viscosity muds - reducing mud expense, mixing time and creating shorter settling times.

Able to run a desander - The centrifugal"s high volume enables a desander to be operated off the pump discharge while drilling without adding a dedicated desander pump.

6. Sticky clays will stall a centrifugal pump"s flow. Be prepared to reduce your bit load in these conditions and increase your rpm if conditions allow. Yes, clays can be drilled with a centrifugal pump.

7. Centrifugal pumps cannot pump muds over 9.5 lbs./gal. Centrifugal pumps work best with a 9.0 lbs./gal. mud weight or less. High flow rate move cuttings, not heavy mud.

The goal of this article has been to increase awareness of the value of the centrifugal pump and its growing use. Although the centrifugal pump is not flawless, once its different operating techniques are understood, drilling programs are being enhanced with the use of this pump.

If you wish to learn more, please talk directly to centrifugal pump users. Feel free to call me at 314-909-8077 for a centrifugal pump user list. These drillers will gladly share their centrifugal pump experiences.

The positive displacement mud pump is a key component of the drilling process and its lifespan and reliability are critical to a successful operation.

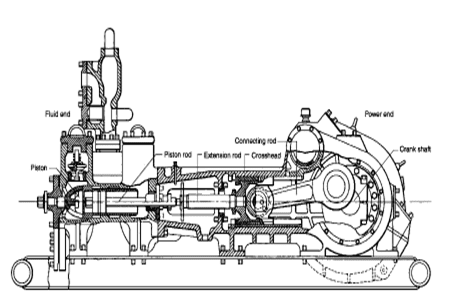

The fluid end is the most easily damaged part of the mud pump. The pumping process occurs within the fluid end with valves, pistons, and liners. Because these components are high-wear items, many pumps are designed to allow quick replacement of these parts.

Due to the nature of its operation, pistons, liners, and valve assemblies will wear and are considered expendable components. There will be some corrosion and metallurgy imperfections, but the majority of pump failures can be traced back to poor maintenance, errors during the repair process, and pumping drilling fluid with excessive solids content.

A few signs include cut piston rubber, discoloration, pistons that are hard to remove, scored liners, valve and seat pitting or cracks, valve inserts severely worn, cracked, or completely missing, and even drilling fluids making their way to the power end of the pump.

The fluid end of a positive displacement triplex pump presents many opportunities for issues. The results of these issues in such a high-pressure system can mean expensive downtime on the pump itself and, possibly, the entire rig — not to mention the costly repair or replacement of the pump. To reduce severe vibration caused by the pumping process, many pumps incorporate both a suction and discharge pulsation dampener; these are connected to the suction and discharge manifolds of the fluid end. These dampeners reduce the cavitation effect on the entire pump which increases the life of everything within the pump.

The fluid end is the most easily damaged part of the mud pump. The pumping process occurs within the fluid end with valves, pistons, and liners. Because these components are high-wear items, many pumps are designed to allow quick replacement of these parts.

Additionally, the throat (inside diameter) can begin to wash out from extended usage hours or rather quickly when the fluid solids content is excessive. When this happens it can cut all the way through the seat and into the fluid end module/seat deck. This causes excessive expense not only from a parts standpoint but also extended downtime for parts delivery and labor hours to remove and replace the fluid module. With that said, a properly operated and maintained mud recycling system is vital to not only the pump but everything the drilling fluid comes in contact with downstream.

The 2,200-hp mud pump for offshore applications is a single-acting reciprocating triplex mud pump designed for high fluid flow rates, even at low operating speeds, and with a long stroke design. These features reduce the number of load reversals in critical components and increase the life of fluid end parts.

The pump’s critical components are strategically placed to make maintenance and inspection far easier and safer. The two-piece, quick-release piston rod lets you remove the piston without disturbing the liner, minimizing downtime when you’re replacing fluid parts.

F04B15/02—Pumps adapted to handle specific fluids, e.g. by selection of specific materials for pumps or pump parts the fluids being viscous or non-homogeneous

A quintuplex mud pump has a crankshaft supported in the pump by external main bearings. The crankshaft has five eccentric sheaves, two internal main bearing sheaves, and two bull gears. Each of the main bearing sheaves supports the crankshaft by a main bearing. One main bearing sheave is disposed between second and third eccentric sheaves, while the other main bearing sheave is disposed between third and fourth eccentric sheaves. One bull gear is disposed between the first and second eccentric sheaves, while the second bull gear is disposed between fourth and fifth eccentric sheaves. A pinion shaft has pinion gears interfacing with the crankshaft"s bull gears. Connecting rods on the eccentric sheaves use roller bearings and transfer rotational movement of the crankshaft to pistons of the pump"s fluid assembly.

Triplex mud pumps pump drilling mud during well operations. An example of a typical triplex mud pump 10 shown in FIG. 1A has a power assembly 12, a crosshead assembly 14, and a fluid assembly 16. Electric motors (not shown) connect to a pinion shaft 30 that drives the power assembly 12. The crosshead assembly 14 converts the rotational movement of the power assembly 12 into reciprocating movement to actuate internal pistons or plungers of the fluid assembly 16. Being triplex, the pump"s fluid assembly 16 has three internal pistons to pump the mud.

As shown in FIG. 1B, the pump"s power assembly 14 has a crankshaft 20 supported at its ends by double roller bearings 22. Positioned along its intermediate extent, the crankshaft 20 has three eccentric sheaves 24-1 . . . 24-3, and three connecting rods 40 mount onto these sheaves 24 with cylindrical roller bearings 26. These connecting rods 40 connect by extension rods (not shown) and the crosshead assembly (14) to the pistons of the pump"s fluid assembly 16.

In addition to the sheaves, the crankshaft 20 also has a bull gear 28 positioned between the second and third sheaves 24-2 and 24-3. The bull gear 28 interfaces with the pinion shaft (30) and drives the crankshaft 20"s rotation. As shown particularly in FIG. 1C, the pinion shaft 30 also mounts in the power assembly 14 with roller bearings 32 supporting its ends. When electric motors couple to the pinion shaft"s ends 34 and rotate the pinion shaft 30, a pinion gear 38 interfacing with the crankshaft"s bull gear 28 drives the crankshaft (20), thereby operating the pistons of the pump"s fluid assembly 16.

When used to pump mud, the triplex mud pump 10 produces flow that varies by approximately 23%. For example, the pump 10 produces a maximum flow level of about 106% during certain crankshaft angles and produces a minimum flow level of 83% during other crankshaft angles, resulting in a total flow variation of 23% as the pump"s pistons are moved in differing exhaust strokes during the crankshaft"s rotation. Because the total flow varies, the pump 10 tends to produce undesirable pressure changes or “noise” in the pumped mud. In turn, this noise interferes with downhole telemetry and other techniques used during measurement-while-drilling (MWD) and logging-while-drilling (LWD) operations.

In contrast to mud pumps, well-service pumps (WSP) are also used during well operations. A well service pump is used to pump fluid at higher pressures than those used to pump mud. Therefore, the well service pumps are typically used to pump high pressure fluid into a well during frac operations or the like. An example of a well-service pump 50 is shown in FIG. 2. Here, the well service pump 50 is a quintuplex well service pump, although triplex well service pumps are also used. The pump 50 has a power assembly 52, a crosshead assembly 54, and a fluid assembly 56. A gear reducer 53 on one side of the pump 50 connects a drive (not shown) to the power assembly 52 to drive the pump 50.

As shown in FIG. 3, the pump"s power assembly 52 has a crankshaft 60 with five crankpins 62 and an internal main bearing sheave 64. The crankpins 62 are offset from the crankshaft 60"s axis of rotation and convert the rotation of the crankshaft 60 in to a reciprocating motion for operating pistons (not shown) in the pump"s fluid assembly 56. Double roller bearings 66 support the crankshaft 60 at both ends of the power assembly 52, and an internal double roller bearing 68 supports the crankshaft 60 at its main bearing sheave 64. One end 61 of the crankshaft 60 extends outside the power assembly 52 for coupling to the gear reducer (53; FIG. 2) and other drive components.

As shown in FIG. 4A, connecting rods 70 connect from the crankpins 62 to pistons or plungers 80 via the crosshead assembly 54. FIG. 4B shows a typical connection of a connecting rod 70 to a crankpin 62 in the well service pump 50. As shown, a bearing cap 74 fits on one side of the crankpin 62 and couples to the profiled end of the connecting rod 70. To reduce friction, the connection uses a sleeve bearing 76 between the rod 70, bearing cap 74, and crankpin 62. From the crankpin 62, the connecting rod 70 connects to a crosshead 55 using a wrist pin 72 as shown in FIG. 4A. The wrist pin 72 allows the connecting rod 70 to pivot with respect to the crosshead 55, which in turn is connected to the plunger 80.

In use, an electric motor or an internal combustion engine (such as a diesel engine) drives the pump 50 by the gear reducer 53. As the crankshaft 60 turns, the crankpins 62 reciprocate the connecting rods 70. Moved by the rods 70, the crossheads 55 reciprocate inside fixed cylinders. In turn, the plunger 80 coupled to the crosshead 55 also reciprocates between suction and power strokes in the fluid assembly 56. Withdrawal of a plunger 80 during a suction stroke pulls fluid into the assembly 56 through the input valve 82 connected to an inlet hose or pipe (not shown). Subsequently pushed during the power stroke, the plunger 80 then forces the fluid under pressure out through the output valve 84 connected to an outlet hose or pipe (not shown).

In contrast to using a crankshaft for a quintuplex well-service pump that has crankpins 62 as discussed above, another type of quintuplex well-service pump uses eccentric sheaves on a direct drive crankshaft. FIG. 4C is an isolated view of such a crankshaft 90 having eccentric sheaves 92-1 . . . 92-5 for use in a quintuplex well-service pump. External main bearings (not shown) support the crankshaft 90 at its ends 96 in the well-service pumps housing (not shown). To drive the crankshaft 90, one end 91 extends beyond the pumps housing for coupling to drive components, such as a gear box. The crankshaft 90 has five eccentric sheaves 92-1 . . . 92-5 for coupling to connecting rods (not shown) with roller bearings. The crankshaft 90 also has two internal main bearing sheaves 94-1, 94-2 for internal main bearings used to support the crankshaft 90 in the pump"s housing.

In the past, quintuplex well-service pumps used for pumping frac fluid or the like have been substituted for mud pumps during drilling operations to pump mud. Unfortunately, the well-service pump has a shorter service life compared to the conventional triplex mud pumps, making use of the well-service pump as a mud pump less desirable in most situations. In addition, a quintuplex well-service pump produces a great deal of white noise that interferes with MWD and LWD operations, further making the pump"s use to pump mud less desirable in most situations. Furthermore, the well-service pump is configured for direct drive by a motor and gear box directly coupling on one end of the crankshaft. This direct coupling limits what drives can be used with the pump. Moreover, the direct drive to the crankshaft can produce various issues with noise, balance, wear, and other associated problems that make use of the well-service pump to pump mud less desirable.

One might expect to provide a quintuplex mud pump by extending the conventional arrangement of a triplex mud pump (e.g., as shown in FIG. 1B) to include components for two additional pistons or plungers. However, the actual design for a quintuplex mud pump is not as easy as extending the conventional arrangement, especially in light of the requirements for a mud pump"s operation such as service life, noise levels, crankshaft deflection, balance, and other considerations. As a result, acceptable implementation of a quintuplex mud pump has not been achieved in the art during the long history of mud pump design.

What is needed is an efficient mud pump that has a long service life and that produces low levels of white noise during operation so as not to interfere with MWD and LWD operations while pumping mud in a well.

A quintuplex mud pump is a continuous duty, reciprocating plunger/piston pump. The mud pump has a crankshaft supported in the pump by external main bearings and uses internal gearing and a pinion shaft to drive the crankshaft. Five eccentric sheaves and two internal main bearing sheaves are provided on the crankshaft. Each of the main bearing sheaves supports the intermediate extent of crankshaft using bearings. One main bearing sheave is disposed between the second and third eccentric sheaves, while the other main bearing sheave is disposed between the third and fourth eccentric sheaves.

One or more bull gears are also provided on the crankshaft, and the pump"s pinion shaft has one or more pinion gears that interface with the one or more bull gears. If one bull gear is used, the interface between the bull and pinion gears can use herringbone or double helical gearing of opposite hand to avoid axial thrust. If two bull gears are used, the interface between the bull and pinion gears can use helical gearing with each having opposite hand to avoid axial thrust. For example, one of two bull gears can be disposed between the first and second eccentric sheaves, while the second bull gear can be disposed between fourth and fifth eccentric sheaves. These bull gears can have opposite hand. The pump"s internal gearing allows the pump to be driven conventionally and packaged in any standard mud pump packaging arrangement. Electric motors (for example, twin motors made by GE) may be used to drive the pump, although the pump"s rated input horsepower may be a factor used to determine the type of motor.

Connecting rods connect to the eccentric sheaves and use roller bearings. During rotation of the crankshaft, these connecting rods transfer the crankshaft"s rotational movement to reciprocating motion of the pistons or plungers in the pump"s fluid assembly. As such, the quintuplex mud pump uses all roller bearings to support its crankshaft and to transfer crankshaft motion to the connecting rods. In this way, the quintuplex mud pump can reduce the white noise typically produced by conventional triplex mud pumps and well service pumps that can interfere with MWD and LWD operations.

Turning to the drawings, a quintuplex mud pump 100 shown in FIGS. 5 and 6A-6B has a power assembly 110, a crosshead assembly 150, and a fluid assembly 170. Twin drives (e.g., electric motors, etc.) couple to ends of the power assembly"s pinion shaft 130 to drive the pump"s power assembly 110. As shown in FIGS. 6A-6B, internal gearing within the power assembly 110 converts the rotation of the pinion shaft 130 to rotation of a crankshaft 120. The gearing uses pinion gears 138 on the pinion shaft 130 that couple to bull gears 128 on the crankshaft 120 and transfer rotation of the pinion shaft 130 to the crankshaft 120.

For support, the crankshaft 120 has external main bearings 122 supporting its ends and two internal main bearings 127 supporting its intermediate extent in the assembly 110. As best shown in FIG. 6A, rotation of the crankshaft 120 reciprocates five independent connecting rods 140. Each of the connecting rods 140 couples to a crosshead 160 of the crosshead assembly 150. In turn, each of the crossheads 160 converts the connecting rod 40"s movement into a reciprocating movement of an intermediate pony rod 166. As it reciprocates, the pony rod 166 drives a coupled piston or plunger (not shown) in the fluid assembly 170 that pumps mud from an intake manifold 192 to an output manifold 198. Being quintuplex, the mud pump 100 has five such pistons movable in the fluid assembly 170 for pumping the mud.

Shown in isolated detail in FIG. 7, the crankshaft 120 has five eccentric sheaves 124-1 through 124-5 disposed thereon. Each of these sheaves can mechanically assemble onto the main vertical extent of the crankshaft 120 as opposed to being welded thereon. During rotation of the crankshaft 120, the eccentric sheaves actuate in a firing order of 124-1, 3, 5, 2 and 4 to operate the fluid assembly"s pistons (not shown). This order allows the crankshaft 120 to be assembled by permitting the various sheaves to be mounted thereon. Preferably, each of the eccentric sheaves 124-1 . . . 124-5 is equidistantly spaced on the crankshaft 120 for balance.

The cross-section in FIG. 10A shows a crosshead 160 for the quintuplex mud pump. The end of the connecting rod 140 couples by a wrist pin 142 and bearing 144 to a crosshead body 162 that is movable in a crosshead guide 164. A pony rod 166 coupled to the crosshead body 162 extends through a stuffing box gasket 168 on a diaphragm plate 169. An end of this pony rod 166 in turn couples to additional components of the fluid assembly (170) as discussed below.

The cross-section in FIG. 10B shows portion of the fluid assembly 170 for the quintuplex mud pump. An intermediate rod 172 has a clamp 174 that couples to the pony rod (166; FIG. 10A) from the crosshead assembly 160 of FIG. 10A. The opposite end of the rod 172 couples by another clamp to a piston rod 180 having a piston head 182 on its end. Although a piston arrangement is shown, the fluid assembly 170 can use a plunger or any other equivalent arrangement so that the terms piston and plunger can be used interchangeably herein. Moved by the pony rod (166), the piston head 182 moves in a liner 184 communicating with a fluid passage 190. As the piston 182 moves, it pulls mud from a suction manifold 192 through a suction valve 194 into the passage 190 and pushes the mud in the passage 190 to a discharge manifold 198 through a discharge valve 196.

As noted previously, a triplex mud pump produces a total flow variation of about 23%. Because the present mud pump 100 is quintuplex, the pump 100 offers a lower variation in total flow, making the pump 100 better suited for pumping mud and producing less noise that can interfere with MWD and LWD operations. In particular, the quintuplex mud pump 100 can produce a total flow variation as low as about 7%. For example, the quintuplex mud pump 100 can produce a maximum flow level of about 102% during certain crankshaft angles and can produce a minimum flow level of 95% during other crankshaft angles as the pump"s five pistons move in their differing strokes during the crankshaft"s rotation. Being smoother and closer to ideal, the lower total flow variation of 7% produces less pressure changes or “noise” in the pumped mud that can interfere with MWD and LWD operations.

Although a quintuplex mud pump is described above, it will be appreciated that the teachings of the present disclosure can be applied to multiplex mud pumps having at least more than three eccentric sheaves, connecting rods, and fluid assembly pistons. Preferably, the arrangement involves an odd number of these components so such mud pumps may be septuplex, nonuplex, etc. For example, a septuplex mud pump according to the present disclosure may have seven eccentric sheaves, connecting rods, and fluid assembly pistons with at least two bull gears and at least two bearing sheaves on the crankshaft. The bull gears can be arranged between first and second eccentric sheaves and sixth and seventh eccentric sheaves on the crankshaft. The internal main bearings supporting the crankshaft can be positioned between third and fourth eccentric sheaves and the fourth and fifth eccentric sheaves on the crankshaft.

a crankshaft rotatably supported in the pump by a plurality of main bearings, the crankshaft having five eccentric sheaves and a first bull gear disposed thereon, the main bearings including a first internal main bearing sheave disposed between the second and third eccentric sheaves and including a second internal main bearing sheave disposed between the third and fourth eccentric sheaves;

a pinion shaft for driving the crankshaft, the pinion shaft rotatably supported in the pump and having a first pinion gear interfacing with the first bull gear on the crankshaft; and

6. A pump of claim 1, wherein the crankshaft comprises a second bull gear disposed thereon, and wherein the pinion shaft comprises a second pinion gear disposed thereon and interfacing with the second bull gear.

7. A pump of claim 6, wherein the first bull gear is disposed between the first and second eccentric sheaves, and wherein the second bull gear is disposed between the fourth and fifth eccentric sheaves.

8. A pump of claim 6, wherein the five eccentric sheaves, the first and second internal main bearing sheaves, and the first and second bull gears are equidistantly spaced from one another on the crankshaft.

9. A pump of claim 6, wherein the first and second pinion gears comprise helical gearing of opposite hand, and wherein the first and second bull gears comprise helical gearing of opposite hand complementary to the pinion gears.

a crankshaft rotatably supported in the pump by two external main bearings and two internal main bearings, the crankshaft having five eccentric sheaves, two internal main bearing sheaves for the internal main bearings, and at least one bull gear disposed thereon;

13. A pump of claim 11, wherein a first of the main bearing sheaves is disposed between the second and third eccentric sheaves, and wherein a second of the main bearing sheaves is disposed between the third and fourth eccentric sheaves.

16. A pump of claim 11, wherein the at least one bull gear comprises first and second bull gears disposed on the crankshaft, and wherein the at least one pinion gear comprises first and second pinion gears disposed on the crankshaft.

17. A pump of claim 16, wherein the first bull gear is disposed between the first and second eccentric sheaves, and wherein the second bull gear is disposed between the fourth and fifth eccentric sheaves.

18. A pump of claim 16, wherein the five eccentric sheaves, the two internal main bearing sheaves, and the first and second bull gears are equidistantly spaced from one another on the crankshaft.

19. A pump of claim 16, wherein the first and second pinion gears comprise helical gearing of opposite hand, and wherein the first and second bull gears comprise helical gearing of opposite hand complementary to the pinion gears.

a crankshaft rotatably supported in the pump by a plurality of main bearings, the crankshaft having five eccentric sheaves and first and second bull gears disposed thereon, the first bull gear disposed between the first and second eccentric sheaves, the second bull gear disposed between the fourth and fifth eccentric sheaves;

a pinion shaft for driving the crankshaft, the pinion shaft rotatably supported in the pump, the pinion shaft having a first pinion gear interfacing with the first bull gear on the crankshaft and having a second pinion gear interfacing with the second bull gear on the crankshaft; and

26. A pump of claim 21, wherein the main bearings include first and second internal main gearing sheaves disposed on the crankshaft, and wherein the five eccentric sheaves, the two internal main bearing sheaves, and the first and second bull gears are equidistantly spaced from one another on the crankshaft.

27. A pump of claim 21, wherein the first and second pinion gears comprise helical gearing of opposite hand, and wherein the first and second bull gears comprise helical gearing of opposite hand complementary to the pinion gears.

a crankshaft rotatably supported in the pump by a plurality of main bearings, the crankshaft having five eccentric sheaves and first and second bull gears disposed thereon, the main bearings including two internal main bearing sheaves disposed on the crankshaft, wherein the five eccentric sheaves, the two internal main bearing sheaves, and the first and second bull gears are equidistantly spaced from one another on the crankshaft;

a pinion shaft for driving the crankshaft, the pinion shaft rotatably supported in the pump, the pinion shaft having a first pinion gear interfacing with the first bull gear on the crankshaft and having a second pinion gear interfacing with the second bull gear on the crankshaft; and

34. A pump of claim 29, wherein the first and second pinion gears comprise helical gearing of opposite hand, and wherein the first and second bull gears comprise helical gearing of opposite hand complementary to the pinion gears.

"Triplex Mud Pump Parts and Accessories;" Product Information Brochure; copyright 2007 Sunnda LLC; downloaded from http://www.triplexmudpump.com/triplex-mud-pump-parts.php on Sep. 5, 2008.

"Triplex Mud Pumps Triplex Mud Pump Parts for Sale;" copyright 2007 Sunnda LLC; Product Information Brochure located at http://www.triplexmudpump.com/.

"Triplex Mud Pumps Triplex Mud Pump Parts;" copyright 2007 Sunnda LLC; downloaded from http://www.triplexmudpump.com/F-series-triplex-mud-pumps-power-end.php on Sep. 5, 2008.

China Petrochemical International Co., Ltd.; "Quintuplex Mud Pump;" Product Information Brochure downloaded from http://www.intl.sinopec.com.cn/emExp/upstream/Quituplex-Mud-Pump.htm downloaded on Oct. 2, 2008.

FMC Technologies; "Fluid Control: Well Service Pump;" Product Information Brochure; downloaded from http://www.fmctechnologies.com/-FluidControl-old/WellServicePump.aspx on Sep. 5, 2008.

National Oilwell; "Triplex Mud Pumps;" Product Information Brochure; downloaded from http://nql.com/Archives/2000%20Composite%20Catalog/pg-32.html downloaded on Sep. 5, 2008.

My first days as an MWD field tech I heard horror stories surrounding what is commonly referred to as “pump noise”. I quickly identified the importance of learning to properly identify this “noise”. From the way it was explained to me, this skill might prevent the company you work from losing a job with an exploration company, satisfy your supervisor or even allow you to become regarded as hero within your organization if you’ve proven yourself handy at this skill.

“Pump noise” is a reference to an instability in surface pressure created by the mud pumps on a modern drilling rig, often conflated with any pressure fluctuation at a similar frequency to pulses generated by a mud pulser, but caused by a source external to the mud pulser. This change in pressure is what stands in the way of the decoder properly understanding what the MWD tool is trying to communicate. For the better part of the first year of learning my role I wrongly assumed that all “noise” would be something audible to the human ear, but this is rarely the case.

A mud pulser is a valve that briefly inhibits flow of drilling fluid traveling through the drill string, creating a sharp rise and fall of pressure seen on surface, also known as a “pulse”.

Depending on if the drilling fluid is being circulated in closed or open loop, it will be drawn from a tank or a plastic lined reservoir by a series(or one) mud pumps and channeled into the stand pipe, which runs up the derrick to the Kelly-hose, through the saver sub and down the drill-pipe(drill-string). Through the filter screen past an agitator or exciter, around the MWD tool, through a mud motor and out of the nozzles in the bit. At this point the fluid begins it’s journey back to the drilling rig through the annulus, past the BOP then out of the flow line and either over the shale shakers and/or back in the fluid reservoir.

Developing a firm grasp on these fundamentals were instrumental in my success as a field technician and an effective troubleshooter. As you can tell, there are a lot of components involved in this conduit which a mud pulser telemeters through. The way in which many of these components interact with the drilling fluid can suddenly change in ways that slightly create sharp changes in pressure, often referred to as “noise”. This “noise” creates difficulty for the decoder by suddenly reducing or increasing pressure in a manner that the decoder interprets a pulse. To isolate these issues, you must first acknowledge potential of their existence. I will give few examples of some of these instances below:

Suction screens on intake hoses will occasionally be too large, fail or become unfastened thus allowing large debris in the mud system. Depending on the size of debris and a little bit of luck it can end up in an area that will inhibit flow, circumstantially resulting in a sudden fluctuation of pressure.

This specifically is a term used to refer to the mud motor stator rubber deterioration, tearing into small pieces and passing through the nozzles of the bit. Brief spikes in pressure as chunks of rubber pass through one or more nozzles of the bit can often be wrongly interpreted as pulses.

Sometimes when mud is displaced or a pump suction isn’t completely submerged, tiny air bubbles are introduced into the drilling fluid. Being that air compresses and fluid does not, pulses can be significantly diminished and sometimes non-existent.

As many of you know the downhole mud motor is what enables most drilling rigs to steer a well to a targeted location. The motor generates bit RPM by converting fluid velocity to rotor/bit RPM, otherwise known as hydraulic horsepower. Anything downhole that interacts with the bit will inevitably affect surface pressure. One of the most common is bit weight. As bit weight is increased, so does surface pressure. It’s important to note that consistent weight tends to be helpful to the decoder by increasing the amplitude of pulses, but inconsistent bit weight, depending on frequency of change, can negatively affect decoding. Bit bounce, bit bite and inconsistent weight transfer can all cause pressure oscillation resulting in poor decoding. Improper bit speed or bit type relative to a given formation are other examples of possible culprits as well.

Over time mud pump components wear to the point failure. Pump pistons(swabs), liners, valves and valve seats are all necessary components for generating stable pressure. These are the moving parts on the fluid side of the pump and the most frequent point of failure. Another possible culprit but less common is an inadequately charged pulsation dampener. Deteriorating rubber hoses anywhere in the fluid path, from the mud pump to the saver sub, such as a kelly-hose, can cause an occasional pressure oscillation.

If I could change one thing about today’s directional drilling industry, it would be eliminating the term “pump noise”. The misleading term alone has caused confusion for countless people working on a drilling rig. On the other hand, I’m happy to have learned these lessons the hard way because they seem engrained into my memory. As technology improves, so does the opportunities for MWD technology companies to provide useful solutions. Solutions to aid MWD service providers to properly isolate or overcome the challenges that lead to decoding issues. As an industry we have come a lot further from when I had started, but there is much left to be desired. I’m happy I can use my experiences by contributing to an organization capable of acknowledging and overcoming these obstacles through the development of new technology.

For drilling companies with the need to pump slurries with bentonite, concrete, and other thick mud, Elepump triplex, high pressure piston mud pumps are the ideal choice for long life and minimal maintenance.

Featuring superior construction and high quality materials, Elepump mud pumps are built to last. They require minimal maintenance, so your costs stay low so and your drilling operations stay profitable.

The KT-45 mud pump is the most compact of the whole range of Elepump pressure pumps. This small capacity pump is still mighty enough to pack a big punch, with enough flow for drilling up to HQ sizes. It is very light and very maneuverable, making it a great choice for geotechnical drilling, fly jobs or heliportable jobs. Elepump mud pumps can be configured for diesel, gas, electric and air power.

The KF-50M is the pump to choose if you want a pump you can count on to keep pumping without missing a beat. This powerful pump is a standard size and can handle all slurries including bentonite, concrete and more. With its stainless steel ball and seat style valves, it is the ideal choice for pumping grit, cement, chunks of rock and other hard material, without the worry of damage to fragile parts. Elepump mud pumps can be configured for diesel, gas, electric and air power.

Insufficient NPSH AvailableSuction pressure is incorrect meaning pump is cavitating. Ensure all valves are open, check liquid temperature. To correct increase fluid in tank, check for air ingress, remove unnecessary bends, increase pipe diameter, install feed pump.

Ensure all valves are open, check liquid temperature. To correct increase fluid in tank, check for air ingress, remove unnecessary bends, increase pipe diameter, reduce fluid temperature, install feed pump.

PulsationSuction pressure is incorrect meaning pump is cavitating. Ensure all valves are open, check liquid temperature. To correct increase fluid in tank, check for air ingress, remove unnecessary bends, increase pipe diameter, reduce fluid temperature, install feed pump.

Inlet pressure too HighMaximum inlet pressure for piston pumps is 40psi (2.75 bar) and plunger pumps is 60-70psi (4-4.8bar). K Style pumps can accept higher inlet pressures.

Pump Dry RunningCheck Fluid level and that NPSHR is being met. Check inlet pipework, and filters for blockage, long suction lines, and presence of air ingress

Water in CrankcaseSpraying / Air CondensationProtect pump from direct spray with ventilated enclosure if necessary. Contaminated oil will damage bearings and other components within the drive.

Worn AdaptorSplit manifold designs of pumps have adapters within the pumps. Check O rings when servicing seals and valves and replace as required.

Manifold Wear / DamageCheck chemical compatibility of fluid and any cleaning fluids used. Operation with worn seals and o rings can accelerate manifold wear. Erosion can be limited by freshwater flushing between pump use.

Manifolds can be damaged by over pressure which may be caused by high inlet pressure, relief valve or regulating valve failure or blockage within pump.

8613371530291

8613371530291