overshot weave free sample

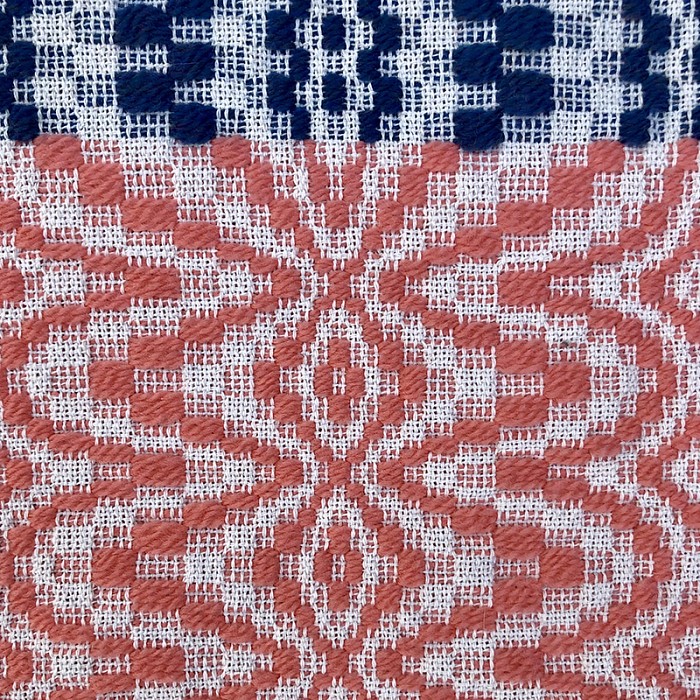

An old pattern in overshot weaving that has had many names over time: Muscadine Hills, Hickory Leaf, Blooming Leaf. The Double Bow Knot name comes from the leaf like square that forms the larger portion of the design. The dark square is called a table. #weaving #overshot #coverlet #history

This post is the third in a series introducing you to common weaving structures. We’ve already looked at plain weave and twill, and this time we’re going to dive into the magic of overshot weaves—a structure that’s very fun to make and creates exciting graphic patterns.

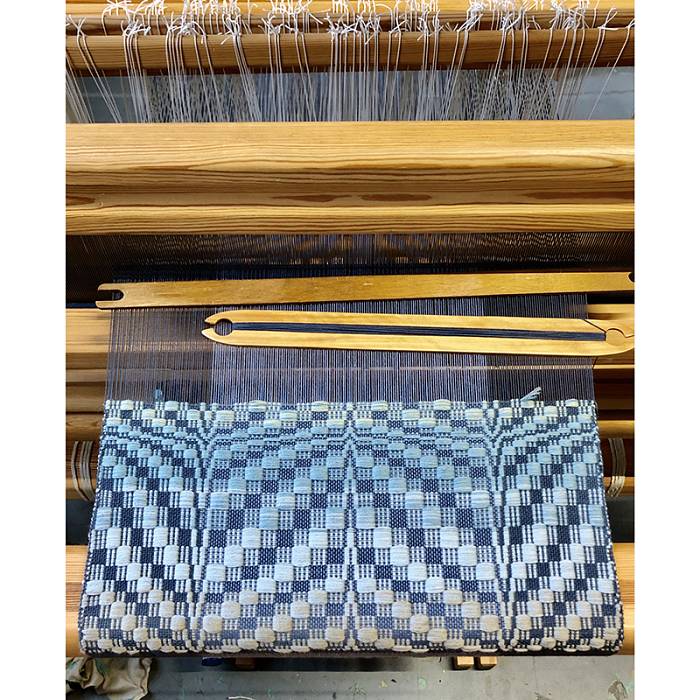

Overshot is a term commonly used to refer to a twill-based type of weaving structure. Perhaps more correctly termed "floatwork" (more on that later), these textiles have a distinctive construction made up of both a plain weave and pattern layer. Requiring two shuttles and at least four shafts, overshot textiles are built using two passes: one weaves a tabby layer and the other weaves a pattern layer, which overshoots or floats, above.

Readers in the United States and Canada may be familiar with overshot textiles through woven coverlets made by early Scottish and English settlers. Using this relatively simple technique, a local professional weaver with a four-shaft loom could easily make a near-infinite variety of equally beautiful and complex patterns. If you’d like to learn more about overshot coverlets and some of the traditions that settlers brought with them, please see my reading list at the bottom of this article!

As it is twill-based, overshot will be very familiar to 4 shaft weavers. It’s made up of a sequence of 2-thread repeats: 1-2, 2-3, 3-4, and 1-4. These sequences can be repeated any number of times to elongate and create lines, curves, and shapes. These 2-thread repeats are often referred to as blocks or threading repeats, IE: 1-2 = block 1/A, 2-3 = block 2/B.

There are three ways weft appears on the face of an overshot cloth: as a solid, half-tone, or blank. In the draft image I’ve shared here, you can see an example of each—the solid is in circled in blue, the half-tone in red, and the blank yellow. Pressing down the first treadle (shafts 1 and 2), for example, creates solid tones everywhere there are threads on shafts 1 and 2, half-tones where there is a 1 or 2 paired with 3 or 4, and nothing on the opposite block, shafts 3 and 4. Of course, there’s not really nothing—the thread is simply traveling on the back of the cloth, creating a reverse of what’s on the face.

Because overshot sequences are always made up of alternating shafts, plain weave can be woven by tying two treadles to lift or lower shafts 1-3 and 2-4. When I weave two-shuttle weaves like overshot, I generally put my tabby treadles to the right and treadle my pattern picks with my left foot and my tabby with my right. In the draft image I’ve shared above, I’ve omitted the tabby picks to make the overarching pattern clearer and easier to read. Below is a draft image that includes the tabby picks to show the structure of the fabric.

Traditional overshot coverlets used cotton or linen for warp and plain weave wefts, and wool pattern wefts—but there’s no rule saying you have to stick to that! In the two overshot patterns I’ve written for Gist, I used both Mallo and Beam as my pattern wefts.

In the Tidal Towels, a very simple overshot threading creates an undulating wave motif across the project. It’s easy and repetitive to thread, and since the overshot section is relatively short, it’s an easy way to get a feel for the technique.

The Bloom Table Squares are designed to introduce you to a slightly more complex threading—but in a short, easy-to-read motif. When I was a new weaver, one of the most challenging things was reading and keeping track of overshot threading and treadling—but I’ve tried to make it easy to practice through this narrow and quick project.

Overshot works best with a pattern weft that 2-4 times larger than your plain weave ground, but I haven’t always followed that rule, and I encourage you to sample and test your own wefts to see how they look! In the samples I wove for this article, I used 8/2 Un-Mercerized Cotton weaving yarn in Beige for my plain weave, and Duet in Rust, Mallo in Brick, and Beam in Blush for my pattern wefts.

The Bloom Table Squares are an excellent example of what weavers usually mean when they talk about traditional overshot or colonial overshot, but I prefer to use the term "floatwork" when talking about overshot. I learned this from the fantastic weaver and textile historian Deborah Livingston-Lowe of Upper Canada Weaving. Having researched the technique thoroughly for her MA thesis, Deborah found that the term "overshot" originated sometime in the 1930s and that historical records variably called these weaves "single coverlets’ or ‘shotover designs.’ Deborah settled on the term "floatwork" to speak about these textiles since it provides a more accurate description of what’s happening in the cloth, and it’s one that I’ve since adopted.

Long out of print, this fabulous book covers the Burnham’s extensive collection of early settler textiles from across Canada, including basic threading drafts and valuable information about professional weavers, tools, and history.

Amanda Ratajis an artist and weaver living and working in Hamilton, Ontario. She studied at the Ontario College of Art and Design University and has developed her contemporary craft practice through research-based projects, artist residencies, professional exhibitions, and lectures. Subscribe to herstudio newsletteror follow her onInstagramto learn about new weaving patterns, exhibitions, projects, and more.

I am beginning my 30th year of handweaving, and find I am not a true “hard core” academic (I may not have that laser focus). I love to teach and love working with people in general. I excel at small groups and one on one, solving problems as we weave together. I love to research and curate information about weaving especially in the 1700s to early 1900s. I want to be part of the solution to identify and keep handweaving history and technical information in the accessible in public domain as much as possible. But, at the same time software is not free, and web servers cost money to run. Keeping something alive will require a business model that generates supportable income in to the future after I am gone. I know that I do not have the physical strength/endurance or the time to be a production weaver, I am a designer at heart. I love to solve problems, and then I move on to the next problem.

With COVID-19 I lost my opportunity to demonstrate handweaving to the public by letting the new weavers try the looms for themselves, and have retreated into my studio. While being in the studio, I decided that I could once again concentrate on historic research and drafting of contemporary versions of old patterns. I discovered that many of the designs I had created earlier in my career were no longer accessible because of the software going out of production, or becoming so expensive you needed to be a production weaver to be able to afford it. I have been dedicating my free time to capturing what data I could from these drafts and I will be transferring them into a more usable format for future generations to enjoy. As I complete the task I will post them to the website. I can not list them for free, because I need to cover sample production and web hosting hosting costs.

I have both 8 shaft looms, a computer-dobby 24 shaft loom, and a very large drawloom. I design for all three types of looms. In the shop I have decided to mark the number of shafts needed for a draft at the top of the description so as not to disappoint a weaver. You will know what you purchasing before you hit the download button. I also also elected to include weaving software files and manual draft files in the same draft archive packages so that people no longer have to choose one or the other.

A few more words about the work I believe I can deliver to the public. I like to design drafts and weave it before I post it to ensure accuracy, but at this point some days I do more designing than weaving. I think I would like to work out a system with a fellow weaver(s), I would like to see I if can afford to pay a weaver to weave samples of these designs that I can post on the website and give credit for the work that was done. I have no worries if you determine that you would like to weave the design for production and sell items. I am aware that drafts can not be copyrighted, and so will not chase you down if you use a my design for sale in your shop. As I have mentioned before, it is not my intent to be a production weaver. If a weaver were interested in this type of arrangement, I would ask that you email me directly with what your financial requirements might be for making samples and what type of loom (mostly number of shafts) you are using for sampling. Sample sizes should be 10″ x 10″ or larger if the draft requires it for a full repeat. I am interested in high contrast samples so that it is clear to the weaver what is happening between the warp and weft threads.

For weavers downloading designs, please understand you are supporting my ability to create and maintain self sustaining a database of information related to weaving for access by yourself and other weavers. Downloading once and sharing widely with others defeats the business case for website sustainability. The drafts will have less value, and we all lose the resources we need to keep historic weaving documents and drafts available to the public. I also believe that I do not want to require a subscription to access the draft data or the learning that I have gathered. So this website will always have a public front end that is useful and full featured that is free.

I do not feel that I am in competition with sites like some international pattern libraries or handweaving.net. Historicweaving.com as a website predates them. I am not intending to scan books, or digitize a drafts in that way. I want to use the historic drafts to study how and why they were made, what makes them look the way they do, and how they can be modified to make new designs that reflect our time and current tastes. Understand my statement above that I am not a pure academic, who is driven to study the past and document it a completely as possible. I want to see the past, and bring it to back to life in an approachable way for today’s weavers and looms. My site will be different than others as I am different weaver. I have had this dream for a long time, and have spent that time learning about weaving and weaving software. I like to use Facebook as my studio blog, because Facebook can moderate comments faster and more safely. I want this expanded website for its database potential, and the ability to generate revenue to keep it self sustaining. I use Pinterest as a visual catalogue of ideas (a designer’s morgue file) to explore in the future. I’m learning how to write and present full digital content, some video, some pictorial, some e-books and stories. I believe we all learn in different ways and I want to explore ways to help other weaver’s pass on their notes/journals/drafts to the future as well. I have taken a few months to reflect on what I really want to do and how I want to spend my time. I want to research and to weave. (Ideally, I would like to travel as well, but that will take time and a vaccine.)

If I offer an handwoven item in my shop for sale it is most likely to be a one of kind – if it is not, the size of the edition will be stated. I have no desire to weave long warps of the same pattern. It slows me down once I have solved the design problem, I like to move on to the next. I like efficiency, but I am far more likely to want to achieve accuracy, especially in complex structures. I have been known to weave, unweave and rethread multiple times until I get the loom to match the draft. I spend more time finding ways to warp and weave better. I am known to innovate. If someone asks me how long it took to weave this particular item, it is hard to answer directly because I have to determine if should I tell you about all of the samples I made before I achieved success. (Again, note, I am not a production weaver). What will make my hand woven gifts special is you can be certain that you will not find another one just like it anywhere. When I use my looms I use them as close to their full capability as possible. My personal patterns are complex on purpose, I have a special hand loom, a 100 shaft combination drawloom and I like to show what it can do. To purchase a handwoven piece from me, pricing includes the cost of overhead for maintaining full weaver’s studio, time spent learning about weaving, the cost of materials and fact the item is unique. Your purchase dollars support my research efforts directly. I reinvest my profit dollars into the website and new weaving history research opportunities.

I began with creating an Illustrated Weaving Glossary meant for beginning weavers – https://historicweaving.com/wordpress/product/illustrated-weaving-glossary/ – never get confused about when a word is used and what it is referring to.

I have been researching extensively for the past couple of yearsMary Meigs Atwater’s Shuttle Craft Guild – Lessons and her American Handweaving Book. Many of the documents I am working from are now in the public domain because their initial publication was 100 years ago, and are even more significant because they are her attempts to record information that was sent to her from other hand weavers throughout the United States. These items are truly meant to be preserved for the public because they came from the public. Since their initial publication, draft notation standards for these structures and patterns have changed significantly, usually it requires a bit of detailed reading to learn how to read the drafts from the manuscript.

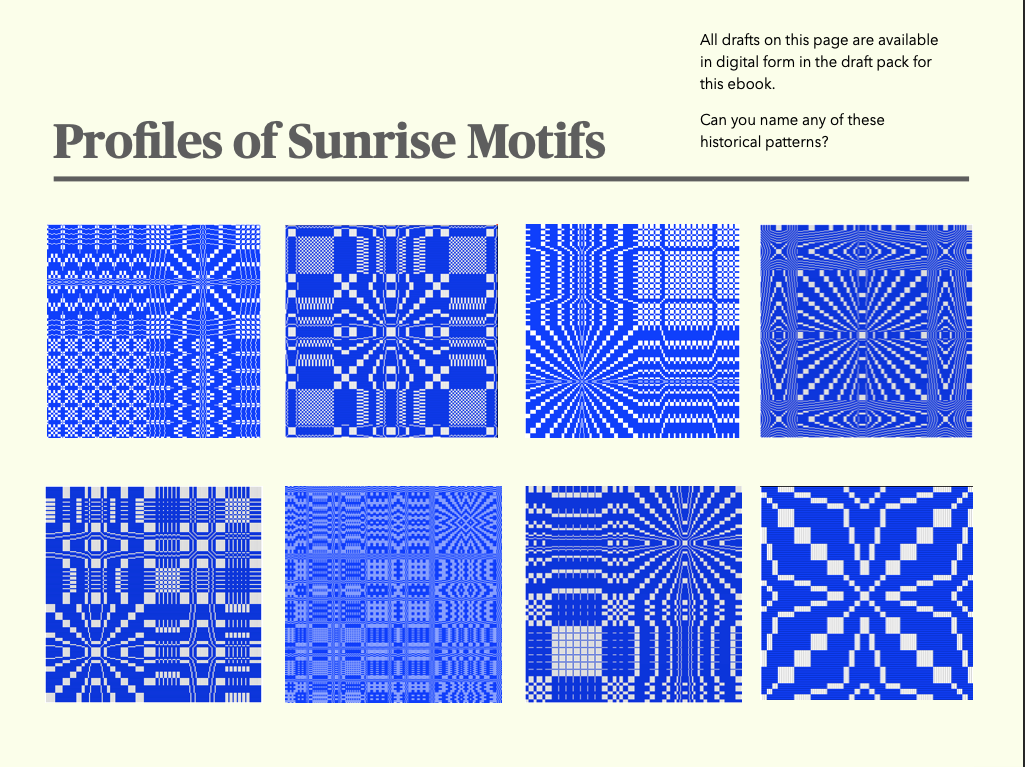

I have taken the time to record some of the larger coverlet radiating overshot pattern drafts in profile draft form making them more accessible to weavers who use drafting software. From the profile you can try different structures, colors and layouts to find a design that is pleasing to you. I have built instructions that show you how the draft is composed and how it can be modified. I would like to think of it as giving you design components more than a formal project plan. If you want the formal project plan approach use the Woven as Drawn in instructions. My goal in my presentation is to increase your understanding so that you can design your own projects and not not to restrict you to copying standardized patterns.

I added an eBook/PDF and draft package for Radiating Overshot Patterns – Sunrise, Blooming Leaf, Bow Knot and the Double Bow Knot. These designs include full drafts, profile drafts and woven as drawn-in drafts. This is the link to purchase the draft archive and the instruction ebook: https://historicweaving.com/wordpress/product/radiating-patterns-for-historic-overshot/

A contemporary version of the Lee’s Surrender draft, using a unit tie weave that can be woven on 6 shafts. In this archive there are colored versions of Lee’s Surrender as found in museum collections.

I am turning my attention to the weaver’s draft books in the United States in the late 1700’s how they got here and the influence they had. I have in my hands access to most of these books and some scholarly research to guide my efforts.

Overshot is the most American and most Canadian of weave structures. I’m not saying that the U.S. and Canada are the only countries that can claim overshot or that they invented the structure. What I am saying is that weavers north and south took the overshot drafts brought over from Europe and made them their own.

To understand the reason for overshot’s popularity, you need to understand the weavers of pre-Industrial Revolution America and Canada. With the exception of those who worked on luxury, specialized fabrics, most weavers made household linens. The cloth needed to be strong and serviceable, and there was little room for experimentation or creativity—except, of course, for coverlets. Coverlets were functional items, but they also served the purpose of decoration. So, weavers of coverlets were free to play at the loom—and play they did.

The reason that weavers loved overshot then is much the same reason that many of us love it now—it’s a simple structure that produces complex patterning on just 4 shafts. With overshot, you can create circles, stars, flowers, and more. It’s also easy to take a draft and adjust it to create seemingly endless variations, which is exactly what happened during the 1700s and beyond. Household weavers would riff on drafts to create new designs, give them names, and then share the drafts with other weavers near and far.

As you might expect, it was not uncommon for multiple weavers to “discover” the same draft without realizing it, nor for them to assign it different names. These names sometimes described what the weaver saw in the pattern—and, often, weavers saw very different things. Take, for example, Marguerite Porter Davison’s Ancient Rose pattern: In other texts, it’s known as Chariot Wheels. On a more whimsical note, Governor’s Garden was also known, at one point, as Rocky Mountain Cucumber because, apparently to someone, the design looked less like flowers and more like a cut cucumber.

In fact, you can find more delightful stories and names in Hall’s book, which is available for free here. The book, which contains a wealth of information on traditional coverlets and designs, is well worth a read. For further reading, I have to suggest Ozark Coverlets: The Shiloh Museum of Ozark History Collection, by Martha “Marty” Benson and Laura Lyon Redford. It’s my favorite book on coverlets, and it beautifully covers (no pun intended) the history of Ozark coverlet weaving and the lives of those weavers, and, best of all, it includes modern drafts of the designs.

In this article, I focus on designing with overshot blocks in order to create flowing curves large enough to be seen at a distance. I will also discuss "weaving as overshot" which is a method of applying overshot techniques to other weave structures and, finally, finish up with some strategies for designing curves in any weave structure.

Any weave structure with at least three blocks can produce diagonals. All you need is a diagonal progression in the threading with a corresponding diagonal progression in the tie-up and treadling. The simplest diagonal draft possible is a three-shaft twill.

In the twill draft above, the diagonal lines are only three threads apart, which might be too subtle an effect. To make the scale of your design larger, you can use a diagonal progression of weave-structure blocks instead of individual threads. The following draft shows an example of a diagonal progression using overshot blocks on four shafts.

Overshot is a weave structure creating a plain-weave cloth with decorative supplementary weft floats. These floats lie on top of (float over) the ground cloth. If you pull out all of the pattern weft threads, you are left with a plain weave cloth formed by the warp and the tabby weft. There are never any warp floats because of the tabby weft.

The tabby weft interlaces with the warp to form the plain weave background, so the tabby weft should be of similar value to blend visually with the warp. It does not have to be the same color as the warp. The tabby weft may the the same size as the warp, but I prefer to use a finer yarn for my tabby weft and a thicker yarn for my pattern weft.

As an example, if my warp is 8/2 cotton sett at 20 epi (recommended for plain weave) in white, my tabby weft will be 10/2 cotton, or perhaps 12/2. If my tabby weft is light blue, then the plain weave cloth will have a white warp and pale blue weft. I can change the color of the background by changing the color of the tabby weft.

Weaving software is very helpful for testing hues and values for weft yarns to use with your warp. If you choose to weave overshot with a single shuttle, choose a contrasting value to the warp for a subtle design but faster weaving.

If you put the curve in your threading, the waves travel across the fabric horizontally, in the direction of the weft. You can see this in the overshot draft below.

I learned how to make curves by studying a traditional overshot draft called Blooming Leaf (page 133 in A Handweaver"s Pattern Book by Marguerite Davison). In this draft, the treadling maintains a diagonal progression but the scale changes to make the shape "bloom" and undulate.

[Note: When I create overshot drafts, I place the first pattern block on treadle three; I like to weave the tabby picks with my left foot (alternating between treadles one and two) and use my right foot (on the remaining treadles) to weave the pattern weft and create the design.]

Now that you know how to create curves, undulations, and reflected curves, you have the tools you need to create any kind of curve or diagonal line in four-shaft overshot. For a challenge, try making a long curve followed by a short curve, like a meandering river.

The methods described above also work for overshot on six, eight, ten, or more shafts. As you add additional shafts to your design, you gain the ability to create smoother and more dramatic curves.

Below is an example of an eight-shaft overshot threading; in this case a diagonal progression with a point and mirror symmetry. My treadling in this draft is an S-shaped curve. This is just one example of the many different curves you can weave on this threading.

Because the underlying structure of overshot is plain weave, any threading which can produce plain weave can theoretically be woven as overshot, alternating tabby and pattern weft.

I wove the draft above using a 20/2 silk sett at 30 epi. I chose to sett the yarn this densely so I could weave both an overshot and twill version on the same warp. You can see the resulting cloth in the picture below.

How do I weave as overshot when my sett is more appropriate for twill? I use a tabby weft that is much finer than the warp, in this case 140/2 silk from Lunatic Fringe.

For example, the warp in the cloth below is hand-dyed in hot shades of red and orange. I chose a red tabby weft, so the background cloth would be very bright. For the pattern weft, I used a dark-purple yarn, with a deeper value than the background cloth. Because the pattern weft floats on top of the plain-weave ground cloth, it creates a textural, raised design element, which emphasizes the curved pattern.

Other times I choose to weave as overshot because the floats show off the pattern-weft yarn, such as the handspun wool used as the pattern weft in the cloth below.

It is easy and fun to make up a curved treadling at the loom, especially when weaving as overshot. Even after forty-two years of weaving, I still enjoy working with long, non-repeating treadlings; watching the curves grow and change as I weave. Instead of memorizing a sequence and repeating it carefully, I watch the design and think about where I want the next curve to go.

The drape of overshot fabric is not as fluid as that of a twill fabric. So for a scarf or shawl I might choose a structure other than overshot. Fine silk, however, has such nice drape that I can weave as overshot and still get good results.

Using two shuttles sometimes produces messier selvedges than a single-shuttle weave, because of the need to interlock the wefts at the edge of the fabric.

In order to create a diagonal line, you need at least three blocks of pattern. The number of shafts you need on your loom to weave three pattern blocks depends on the weave structure. Some structures, such as double weave, require several shafts per pattern block, whereas others, like summer and winter, are shaft thrifty.

In order to create curves, you must be able to lengthen an area to change the slope of the diagonal line while maintaining the weave structure. That’s it!

Generally this means repeating a treadling block. With a diagonal progression in the threading, you can treadle curves as long or short as you like. This applies to all weave structures.

With weaving software, it is easy to create curved overshot designs. Simply draw a freehand curve in the treadling—smoothing it out if necessary—and then add the tabby shots. Once you have the general idea from designing drafts, you can improvise new curved designs at the loom.

For other weave structures, creating a profile draft can be helpful. A profile draft is a design template that represents the woven design at one level of abstraction. To convert a profile draft into a weaving draft, you replace each block in a profile draft with the appropriate block of a given weave structure. You can, therefore, express a single profile draft in many different weave structures: overshot, summer-and-winter, Bronson lace, huck lace, double weave, etc.

The weave structure you choose can subtly change the look of the curves you designed in the profile draft. After I use block substitution to express a profile draft into a specific weave structure, I often make changes to the draft to smooth out the curves or make them more graceful.

I like smooth, flowing curves that are visible at a distance. So I look for structures that give me the maximum number of pattern blocks to design with. Generally I use weave structures where I have as many pattern blocks as there are shafts on my loom. On a four-shaft loom, I use crackle, overshot, advancing and network-drafted twills, advancing points, turned taqueté, rep, and shadow weave.

The more you work with any given weave structure, however, the more control you have over it. Weave several different drafts in the same structure and it will become your friend.

Many years ago, I finally got to try weaving. I took the Beginning to Weave workshop through the Ottawa guild. At that time, 1989, the OVWSG did not have a studio space to house what guild equipment we had acquired. (The Guild had an old second-hand 100 inch loom and 6 or 7 table looms. There may have been a floor loom too but I was distracted by the 100 inches of loom, so do not remember). All the looms lived in one of our guild members’ very big basements. On weekends, she either taught weaving workshops or hosted weavers working on the 100 inch loom. It sounded like a busy basement! I remember 4 weekends of driving to a little town just east of Ottawa. I took the table loom home each week to do homework. I still remember the sound of the mettle heddles rattling as I drove down the highway, back and forth to the classes. Then I think there were two more weekends of Intermediate weaving and Dona sent me off and I was weaving!

It all starts with yarn, wind it carefully, attach it to the back beam, wind on, thread the heddles, slay the reed, tie on to the front beam, check the tension and then start to weave. It sounds like a lot of work but it is all worth it as you start to pass the shuttle through the shed and the cloth begins to appear. Weaving was like Magic! From a pile of string to POOF, actual cloth!!!

During the workshop, I found pickup seemed strangely familiar as my brain watched my fingers happily lifting and twisting threads for the various lace and decorative weave patterns. The other thing that my brain went “ooh this is cool!” was Overshot. It is a weave structure that requires a ground and a pattern thread, (two shuttles). One is fine like the warp and the pattern thread is thicker and usually wool. I was still reacting to wool so I used cotton for both. My original goal was to draft and weave a Viking textile for myself but I put that aside for a moment, I will get back to that later.

The first thing I wove after my instruction was a present for my Mom. she had requested fabric to make a vest. I looked through A Handweaver’s Pattern Bookby Marguerite Porter Davison and found an overshot pattern that I thought we both would like. I wove it in two shades of blue (Mom’s favourite colour), at a looser thread count than usual. (Originally the overshot weave structure was used to make coverlets, so were tightly woven and a bit stiff, while I liked the pattern I wanted the fabric to be much more drapey.) Even worse, I did not want it to be as hard-edged in the pattern as it was originally intended so I tried a slub cotton as a test and loved it.

So, for any sane weaver, it was all wrong! Wrong set, wrong fibre, wrong colour choices! It was fabulous and perfect. I kept the sample as a basket cover and at either the end of 1989 or the beginning of 1990, I gave Mom the yardage for her vest. “Oh this is too nice to cut” Mom Said, so it lived on the back of her favourite reading chair as a headrest until her most recent move (2015?) it never did get to be a vest but it has been well enjoyed.

In the Exhibition The Inkle band, hanging beside the overshot, I wove much more recently. I used an Inkle loom and a supplemental warp thread. This means weaving with an extra separate thread that was not part of the main warp on the loom. I used a yarn with a fuzzy caterpillar-like slub.

You may be able to see how I wove the weird slubby supplemental warp. The yarn is weighted and left hanging over the back peg of the Inkle loom. It comes over the top peg (usually labelled B in diagrams) and floats above the weaving. In the areas where the Caterpillar (Slub) is not present I catch the yarn with the shuttle and weave it into the band. In the area the caterpillar appears I would leave the yarn above the warp and then start weaving it in again as I reached the end of the caterpillar. I hope that explanation doesn’t sound like mud and makes a bit of sense. Using a supplemental warp on an Inkle loom is not quite normal but it is a lot of fun.

I was going to tell you about my original goal in learning to weave, the mysterious Fragment #10 from a Viking excavation from around the year 1000, but I have likely confused you with weaving enough for one day. So I will save that for another chat. (don’t forget the Inkle loom I would like to tell you a bit more about that in another post too. I promise I will get back to felting in the not-too-distant future)

I am attempting some upholstery fabric for the first time and decided on Brassard 8/2 cottolin for the warp and Harrisville Shetland for the weft. The structure is “Waldenweave” from Bertha Gray Hayes collection of miniature overshot…. I am developing a “thing” for overshot and really like all aspects of it.

This book features the original sample collection and handwritten drafts of the talented, early 20th century weaver, Bertha Gray Hayes of Providence, Rhode Island. She designed and wove miniature overshot patterns for four-harness looms that are creative and unique. The book contains color reproductions of 72 original sample cards and 20 recently discovered patterns, many shown with a picture of the woven sample, and each with computer-generated drawdowns and drafting patterns.

Her designs are unique in their asymmetry and personal in her use of name drafting to create the designs. Bertha Hayes attended the first nine National Conferences of American Handweavers (1938-1946). She learned to weave by herself through the Shuttle-Craft home course and was a charter member of the Shuttle-Craft Guild, and authored articles on weaving.

About the authors: The Weavers" Guild of Rhode Island was founded in 1947 to promote understanding and the practice of handweaving. It offers monthly programs and workshops, and is an active member of the New England Weavers Seminar.

Over three years ago, when my David Louet floor loom was still somewhat new to me, I wrotethis post on overshot. If you read it, you will discover that my initial relationship with overshot was not a very positive one.

Back then, I was a little harder on myself as a learning weaver. By now, I’ve realised that weaving, just like life, is a journey that has a beginning but no end. Back then, I thought that my ultimate goal was to be a “master weaver”.

Honestly, I don’t even really know what that means but it no longer matters to me. I just want to be the best weaver I can be, but even more importantly, to continue to be fulfilled, challenged and rewarded by doing it.

The happy ending to the initial overshot sob story is that I can weave overshot now. Quite well, in fact! And I also teach it. And I happen to love it, very, very much. Don’t you love a happy ending?

I don’t think there was any particular moment where I thought to myself “I can weave overshot now!” I didn’t even weave any overshot for quite some time after that initial attempt. But slowly it tempted me back, and we started over. It was just a matter of sticking with it, employing some specific techniques and practice, practice, practice until it feels like an old friend.

My love of overshot has only increased with my more recent discovery of American Coverlets. I loved the look of the coverlets and the history behind them before I realised that so many of them were woven in the wonderfully humble 4 shaft overshot.

I’ve put a lot of research time into coverlets this year and have made it a big weaving goal of mine to weave my first coverlet, which is quite an undertaking, but I relish the thought.

Now that I have quite a lot of experience weaving overshot, I want to share my best overshot tips with you in hope that you too will fall in love with this wonderful weave structure.

To weave overshot you need a warp yarn, a tabby yarn and a pattern weft yarn. Using the same yarn for warp and tabby works perfectly. For the pattern weft, I like to use a yarn that is twice the size of the tabby/warp yarn. I have experimented with using doubled strands of tabby/warp yarn in a contrasting colour, but it just doesn’t look as good. A thicker pattern yarn is the way to go.

What will the size of your item be? A miniature overshot pattern may get lost in a blanket, but may be perfect for a scarf. As a general rule, a good way to estimate the size of one repeat of your pattern just by looking at the draft is to see how many repeats are in one threading repeat. Also consider the thickness of your yarns and the sett you intend to weave.

This is a non negotiable for overshot if you want neat edges and less headaches! You get used to using floating selvedges very quickly, so don’t stress if you have no experience with them.

There are 6 treadles needed for overshot, even though you weave on 4 shafts. The two extra treadles are for the tabby weave. I always set up my pattern treadles in the centre of the loom – two on the left and two on the right. Then I set up a “left” tabby and a “right” tabby treadle. To do this on my 8 shaft loom I leave a gap between the pattern treadles and the tabby treadles so that my feet can “see” and differentiate between a pattern and tabby treadle.

I like to advance little and often. You will find your own preference or “sweet spot” for weaving, but I find that with overshot I advance a lot more frequently at a much smaller amount than I do usually.

The firmness of beat will depend on a few things. Your chosen yarns, the weave structure, the width of the project and the tension your warp is under are all important considerations. I let the project dictate.

An example of this is that I wove an overshot sampler right before Is started my main project (the throw). It was a narrow warp (around 8″) and a different overshot threading and treadling than I’m using for the project.

I personally do not use a temple. Some weavers will say they won’t weave without one. I’ve tried using a temple on many of my projects, particularly if I’m getting broken edge warp threads (signs of tension problems and too much draw in). But I will avoid using one wherever I can get away with it, and I don’t use one for weaving overshot.

This book features the original sample collection and handwritten drafts of the talented, early 20th century weaver, Bertha Gray Hayes of Providence, Rhode Island. She designed and wove miniature overshot patterns for four-harness looms that are creative and unique. The book contains color reproductions of 72 original sample cards and 20 recently discovered patterns, many shown with a picture of the woven sample, and each with computer-generated drawdowns and drafting patterns. Her designs are unique in their asymmetry and personal in her use of name drafting to create the designs.

Bertha Hayes attended the first nine National Conferences of American Handweavers (1938-1946). She learned to weave by herself through the Shuttle-Craft home course and was a charter member of the Shuttle-Craft Guild, and authored articles on weaving.

Overshot: The earliest coverlets were woven using an overshot weave. There is a ground cloth of plain weave linen or cotton with a supplementary pattern weft, usually of dyed wool, added to create a geometric pattern based on simple combinations of blocks. The weaver creates the pattern by raising and lowering the pattern weft with treadles to create vibrant, reversible geometric patterns. Overshot coverlets could be woven domestically by men or women on simple four-shaft looms, and the craft persists to this day.

Summer-and-Winter: This structure is a type of overshot with strict rules about supplementary pattern weft float distances. The weft yarns float over no more than two warp yarns. This creates a denser fabric with a tighter weave. Summer-and-Winter is so named because one side of the coverlet features more wool than the other, thus giving the coverlet a summer side and a winter side. This structure may be an American invention. Its origins are somewhat mysterious, but it seems to have evolved out of a British weaving tradition.

Twill:Twill along with plain and satin weave is one of the three simple weave structures. Twill is created by repetition of a regular ratio of warp and weft floats, usually 1:2, 1:3, or 2:4. Twill weave is identifiable by the diagonal orientation of the weave structure. This diagonal can be reversed and combined to create herringbone and diamond effects in the weave.

Double Cloth: Usually associated with professional weavers, double cloth is formed from two plain weave fabrics that swap places with one another, interlocking the textile and creating the pattern. Coverlet weavers initially used German, geometric, block-weaving patterns to create decorative coverlets and ingrain carpeting. These coverlets contain twice the yarn and are twice as heavy as other coverlets.

Beiderwand: Weavers in Northern Germany and Southern Denmark first used this structure in the seventeenth century to weave bed curtains and textiles for clothing. Beiderwand is an integrated structure, and the design alternates sections of warp-faced and weft-faced plain weave. Beiderwand coverlets can be either true Beiderwand or the more common tied-Beiderwand. This structure is identifiable by the ribbed appearance of the textile created by the addition of a supplementary binding warp.

Figured and Fancy: Although not a structure in its own right, Figured and Fancy coverlets can be identified by the appearance of curvilinear designs and woven inscriptions. Weavers could use a variety of technologies and structures to create them including, the cylinder loom, Jacquard mechanism, or weft-loop patterning. Figured and Fancy coverlets were the preferred style throughout much of the nineteenth century. Their manufacture was an important economic and industrial engine in rural America.

Multi-harness/Star and Diamond: This group of coverlets is characterized not by the structure but by the intricacy of patterning. Usually executed in overshot, Beiderwand, or geometric double cloth, these coverlets were made almost all made in Eastern Pennsylvania by professional weavers on looms with between twelve and twenty-six shafts.

America’s earliest coverlets were woven in New England, usually in overshot patterns and by women working collectively to produce textiles for their own homes and for sale locally. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, Age of Homespun examines this pre-Revolutionary economy in which women shared labor, raw materials, and textile equipment to supplement family incomes. As the nineteenth century approached and textile mills emerged first in New England, new groups of European immigrant weavers would arrive in New England before moving westward to cheaper available land and spread industrialization to America’s rural interior.

The coverlets from New York and New Jersey are among the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlets. NMAH possesses the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlet (dated 1817), made on Long Island by an unknown weaver. These coverlets are associated primarily with Scottish and Scots-Irish immigrant weavers who were recruited from Britain to provide a skilled workforce for America’s earliest woolen textile mills, and then established their own businesses. New York and New Jersey coverlets are primarily blue and white, double cloth and feature refined Neoclassical and Victorian motifs. Long Island and the Finger Lakes region of New York as well as Bergen County, New Jersey were major centers of coverlet production.

German immigrant weavers influenced the coverlets of Pennsylvania, Virginia (including West Virginia) and Maryland. Tied-Beiderwand was the structure preferred by most weavers. Horizontal color-banding, German folk motifs like the Distelfinken (thistle finch), and eight-point star and sunbursts are common. Pennsylvania and Mid-Atlantic coverlets tend to favor the inscribed cornerblock complete with weaver’s name, location, date, and customer. There were many regionalized woolen mills and factories throughout Pennsylvania. Most successful of these were Philip Schum and Sons in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and Chatham’s Run Factory, owned by John Rich and better known today as Woolrich Woolen Mills.

Coverlet weavers were among some of the earliest European settler in the Northwest Territories. After helping to clear the land and establish agriculture, these weavers focused their attentions on establishing mills and weaving operations with local supplies, for local markets. This economic pattern helped introduce the American interior to an industrial economy. It also allowed the weaver to free himself and his family from traditional, less-favorable urban factory life. New land in Ohio and Indiana enticed weavers from the New York and Mid-Atlantic traditions to settle in the Northwest Territories. As a result, coverlets from this region hybridized, blending the fondness for color found in Pennsylvania coverlets with the refinement of design and Scottish influence of the New York coverlets.

Southern coverlets almost always tended to be woven in overshot patterns. Traditional hand-weaving also survived longest in the South. Southern Appalachian women were still weaving overshot coverlets at the turn of the twentieth century. These women and their coverlets helped in inspire a wave of Settlement Schools and mail-order cottage industries throughout the Southern Appalachian region, inspiring and contributing to Colonial Revival design and the Handicraft Revival. Before the Civil War, enslaved labor was often used in the production of Southern coverlets, both to grow and process the raw materials, and to transform those materials into a finished product.

Because so many coverlets have been passed down as family heirlooms, retaining documentation on their maker or users, they provide a visual catalog of America’s path toward and response to industrialization. Coverlet weavers have sometimes been categorized as artisan weavers fighting to keep a traditional craft alive. New research, however, is showing that many of these weavers were on the forefront of industry in rural America. Many coverlet weavers began their American odyssey as immigrants, recruited from European textile factories—along with their families—to help establish industrial mills in America. Families saved their money, bought cheaper land in America’s rural interior and took their mechanical skills and ideas about industrial organization into the American heartland. Once there, these weavers found options. They could operate as weaver-farmers, own a small workshop, partner with a local carding mill, or open their own small, regional factories. They were quick to embrace new weaving technologies, including power looms, and frequently advertised in local newspapers. Coverlet weavers created small pockets of residentiary industry that relied on a steady flow of European-trained immigrants. These small factories remained successful until after the Civil War when the railroads made mass-produced, industrial goods more readily available nationwide.

8613371530291

8613371530291