weaving overshot quotation

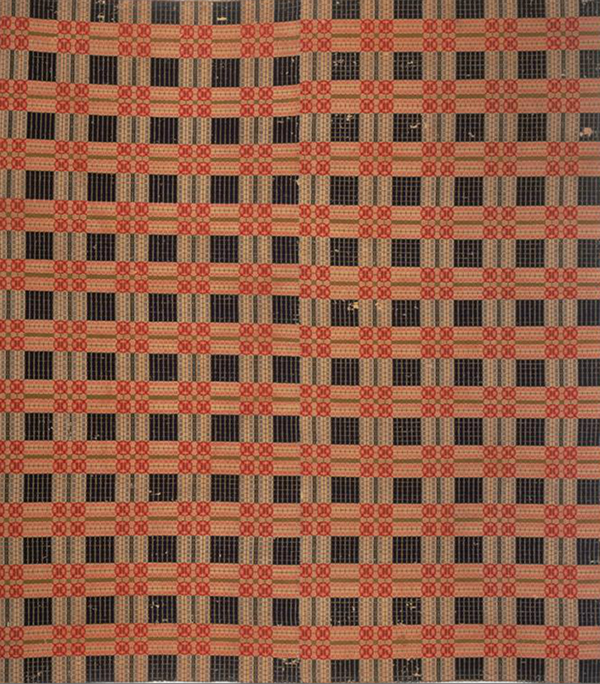

I wove some samples and decided to make this for my scroll. The warp was handspun singles from Bouton. I wanted to see if I could use this fragile cotton for a warp. I used a sizing for the first time in my weaving life. The pattern weft is silk and shows up nicely against the matt cotton.

This illustration and quote are in The Weaving Book by Helen Bress and is the only place I’ve seen this addressed. “Inadvertently, the tabby does another thing. It makes some pattern threads pair together and separates others. On the draw-down [draft], all pattern threads look equidistant from each other. Actually, within any block, the floats will often look more like this: [see illustration]. With some yarns and setts, this pairing is hardly noticeable. If you don’t like the way the floats are pairing, try changing the order of the tabby shots. …and be consistent when treadling mirror-imaged blocks.”

The origin of the technique itself may have started in Persia and spread to other parts of the world, according to the author, Hans E. Wulff, of The Traditional Crafts of Persia. However, it is all relatively obscured by history. In The Key to Weavingby Mary E. Black, she mentioned that one weaver, who was unable to find a legitimate definition of the technique thought that the name “overshot” was a derivative of the idea that “the last thread of one pattern block overshoots the first thread of the next pattern block.” I personally think it is because the pattern weft overshoots the ground warp and weft webbing.

Overshot gained popularity and a place in history during the turn of the 19th century in North America for coverlets. Coverlets are woven bedcovers, often placed as the topmost covering on the bed. A quote that I feel strengthens the craftsmanship and labor that goes into weaving an overshot coverlet is from The National Museum of the American Coverlet:

Though, popular in many states during the early to mid 19th centuries, the extensive development of overshot weaving as a form of design and expression was fostered in rural southern Appalachia. It remained a staple of hand-weavers in the region until the early 20th century. In New England, around 1875, the invention of the Jacquard loom, the success of chemical dyes and the evolution of creating milled yarns, changed the look of coverlets entirely. The designs woven in New England textile mills were predominantly pictorial and curvilinear. So, while the weavers of New England set down their shuttles in favor of complex imagery in their textiles, the weavers of Southern Appalachia continued to weave for at least another hundred years using single strand, hand spun, irregular wool yarn that was dyed with vegetable matter, by choice.

And, due to the nature of design, overshot can be woven on simpler four harness looms. This was a means for many weavers to explore this technique who may not have the financial means to a more complicated loom. With this type of patterning a blanket could be woven in narrower strips and then hand sewn together to cover larger beds. This allowed weavers to create complex patterns that spanned the entirety of the bed.

What makes overshot so incredibly interesting that it was fundamentally a development of American weavers looking to express themselves. Many of the traditional patterns have mysterious names such as “Maltese Cross”, “Liley of the West”, “Blooming Leaf of Mexico” and “Lee’s Surrender”. Although the names are curious, the patterns that were developed from the variations of four simple blocks are incredibly intricate and luxurious.

This is only the tip of the iceberg with regard to the history of this woven structure. If you are interested in learning more about the culture and meaning of overshot, check out these resources!

The National Museum of the American Coverlet- a museum located in Bedford, Pennsylvania that has an extensive collection of traditional and jacquard overshot coverlets. Great information online and they have a “Coverlet College” which is a weekend series of lectures to learn everything about the American coverlet. Check out their website - coverletmuseum.org

Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women – This was an exhibit that traveled from Lowell, Massachusetts, Morehead, Kentucky, Knoxville, Tennessee, Raleigh, North Carolina, and ended at the Royal Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland. The exhibit contained a large number of overshot coverlets and the personal histories of those who wove them. I learned of this exhibit through an article written by Kathryn Liebowitz for the 2001, June/July edition of the magazine “Art New England”. The book that accompanied the exhibit, written by Kathleen Curtis Wilson, contains some of the rich history of these weavers and the cloth they created. I have not personally read the book, but it is now on the top of my wish list, so when I do, you will be the first to know about it! The book is called Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women and I look forward to reading it.

As I began to plan the structure of the piece I knew that using an overshot technique for my weaving would probably give me the visual texture that I desired.

The overshot technique in weaving is accomplished by using two different thickness ofthread alternated in the weaving rows. The pattern row is made using the thicker of the two threads and usually skips over several threads to achieve the desired pattern that you are weaving. The thinner of the two threads is woven across the warp before and after each thicker pattern thread to “lock in” the pattern thread. The thinner threads are woven in tabby (weaving speak for plain weave).

I feel that using the overshot weaving technique helped me to capture the textual feeling I wanted for this runner. Here is how the project progressed and a list of the yarns that were used.

With the color pallet and types of yarn I chose and using the overshot technique, I felt like I was able to achieve the look that I wanted for this project. What do you think??

Half way through my weaving I decided I wanted to add a little something special to the piece that would bring the cultural influence in the tribal shield that inspired me to create this project to begin with. As I searched for that special something, I found a vendor on Etsy that imported fair trade beads from Africa. Handmade metal and hand-carved bone beads. I was pretty excited! Special handmade beads from another artist to compliment a handmade runner, just what the runner needed forthat finishing touch. When the beads arrived I laid them out on the runner that I was almost finished weaving and knew it was definitely the perfect accent!

Adding the beads to the finished runner was a long and tedious task but definitely worth the work, time and effort when I saw the finished project!! Once the beading was finished all that was left was to do the finishing wash and block drying and trimming off any overlapped threads in the weaving.

I actually had some beautiful brass and bone beads leftover from my weaving projects so I made those into some fun jewelry pieces . I’ll have some pictures of those in my next blog post.

One of my favorite parts of working on my Ancient Rose Scarf for the March/April 2019 issue of Handwoven was taking the time to research overshot and how it fits into the history of American weaving. As a former historian, I enjoyed diving into old classics by Lou Tate, Eliza Calvert Hall, and Mary Meigs Atwater, as well as one of my new favorite books, _Ozark Coverlets, by Marty Benson and Laura Lyon Redford Here’s what I wrote in the issue about my design:_

“The Earliest weaving appears to have been limited to the capacity of the simple four-harness loom. Several weaves are possible on this loom, but the one that admits of the widest variations is the so-called ‘four harness overshot weave,’—and this is the foremost of the colonial weaves.” So wrote Mary Meigs Atwater in The Shuttle-Craft Book of American Hand-Weaving when speaking of the American coverlet and the draft s most loved by those early weavers.

Overshot, in my mind, is the most North American of yarn structures. Yes, I know that overshot is woven beyond the borders of North America, but American and Canadian weavers of old took this structure and ran with it. The coverlets woven by weavers north and south provided those individuals with a creative outlet. Coverlets needed to be functional and, ideally, look nice. With (usually) just four shaft s at their disposal, weavers gravitated toward overshot with its stars, roses, and other eye-catching patterns. Using drafts brought to North America from Scotland and Scandinavia, these early weavers devised nearly endless variations and drafts, giving them delightful names and ultimately making them their own.

When I first began designing my overshot scarf, I used the yarn color for inspiration and searched for a draft reminiscent of poppies. I found just what I was looking for in the Ancient Rose pattern in A Handweaver’s Pattern Book. When I look at the pattern, I see poppies; when Marguerite Porter Davison and other weavers looked at it, they saw roses. I found out later that the circular patterns—what looked so much to me like flowers—are also known as chariot wheels.

Weave structures often have specific threading and treadling patterns that are unique to that particular weave structure and not shared with others. This book takes you out of the traditional method of weaving overshot patterns by using different treadling techniques. This will include weaving overshot patterns as Summer/Winter, Italian manner, starburst, crackle, and petit point just to name a few. The basic image is maintained in each example but the design takes on a whole new look!

Each chapter walks you through the setup for each method and includes projects with complete drafts and instructions so it’s easy to start weaving and watch the magic happen! Try the patterns for scarves, table runners, shawls, pillows and even some upholstered pieces. Once you"ve tried a few projects, you"ll be able to apply what you"ve learned to any piece you desire!

One of the coolest things about weaving is that it is generally understood to have emerged at similar times in many different geographical locations around the world. People weave in different ways, for different purposes, and in different conditions. Learning from other weavers has been one of the most valuable experiences to my weaving practice. Since I expect most of us won"t be traveling much in the near future, I figured it was a good time to share some of my most meaningful travel experiences.

I"ve had the opportunity to go to to Mexico, India, Morocco, Europe, and many places in the US and Canada to learn from weaving experts. I’m going to share what I’ve learned along the way.

At first I was hesitant to take up the time of busy weavers. I felt like just another tourist distracting them from their work. Turns out, most of the weavers were really excited to meet a Canadian weaver! After a few interactions, I realized that it wasn"t all take, I had something to GIVE too. It can be tricky trying to communicate with a language barrier, but it isn"t impossible. In many situations in Morocco, I had no Arabic, and most of the weavers had little-no English, so we were both trying to communicate in French which was not great for either of us. The good thing about weaving is that so much of it can be communicated without any language at all. In the above image, I am learning a special weaving knot from Youseph that he learned as a child. After he taught me, I shared with him how I tie on the loom with a surgeons knot. I also helped him to lower his bench so it was more ergonomic. Even though Youseph is a lifelong weaver who drills holes in cards himself to make the patterns on his handmade Jacquard-like loom, I still had a little something to contribute.

Many weavers in North America are fortunate enough to have access to the weaving tools that they need. This isn"t always the case in many of the places I visited. Most of the looms I saw in India, and all of the looms I saw in Morocco were handmade, often by the weaver themselves. Popular scrap materials include toothpicks, bike parts, string, and sticks of all kinds.

I remember once for a project making about 30 string heddles because I had not planned well. I got very grumpy. My perspective is different now for sure. Have you ever been in a weaving situation where necessity was the mother of invention?

I was lucky enough to have a translator in the small town of Sefrou, where I had the opportunity to speak with Mustapha (see above image). He was excited to talk to another weaver and we shared weaving knowledge and stories. He told me that in Arabic, the warping mill is called the “heart,” because without a good warp, the weaving has no life. I think about that now when I use my mill. The translator told me that Mustapha was difficult to translate because he speaks in so many metaphors. Weaving is full of metaphors! How could he not?

Have you seen weaving at all in your travels? If money/time/coronavirus were no object, where would you go? Angela and I would love to hear about your weaving-travel adventures!

8613371530291

8613371530291