4 shaft overshot weaving drafts factory

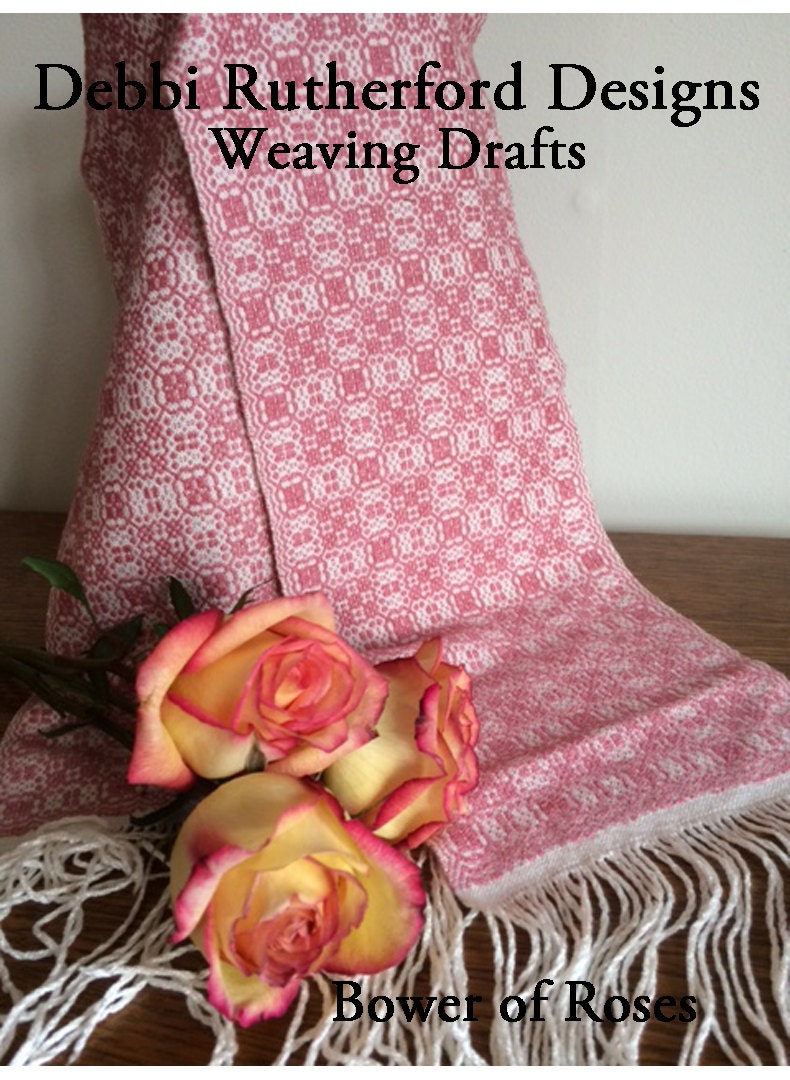

I never really thought of using different colors for overshot before, but after feeling inspired by a group discussion, I decided to try it! I like it a lot and will probably do it again. The warp is pink, yellow, and blue. The tabby weft is the same rotation of pink, yellow, and blue, while…

A book of 100 easy to read and follow drafts for 4 shaft boundweave. Learn how to set up the loom for boundweave, and how to weave a story cloth as a gift or a memory of a special occasion in your life. All drafts are in color, have a standardized Color Legend and an easy to use treadle tracking system so that you do not lose your place when weaving. Book also contains Blank Pattern Drafts template so that you can create your own drafts to tell YOUR unique story.

As weavers it’s not uncommon to come across weaving drafts that are decades or even centuries old. In her article for the November/December 2017 issue of Handwoven, Madelyn van der Hoogt teaches you how to decipher old overshot drafts. Check out the issue to discover more vintage drafts and projects inspired by famous weavers. ~Christina

Overshot is a miracle of design potential on only four shafts. Somewhere, sometime long ago, a weaver looked at 2/2 twill and said: What if I add a tabby weft and repeat each two-thread pair for longer floats? Incredible patterns evolved, shared by colonial weavers with each other on small pieces of precious paper. Luckily, many of these drafts were saved and have become part of our weaving literature. In some of the older sources, the drafting format looks very confusing. Here is a guide to using them.

In the days when paper was hard to come by and writing was done by dipping a quill in ink, drafting formats for weaving were as abbreviated as possible. Overshot patterns are so elaborate that they can’t be communicated by words or short repeats the way simple twills can (point, rosepath, straight, broken, etc.). Complete drafts are necessary. Threading repeats are often long—some with as many as 400 threads. A number of shorthand methods thereby evolved that are similar to our use of profile drafts for other block weaves. But the way overshot works doesn’t allow a strict substitution of threading units for blocks on a profile threading draft.

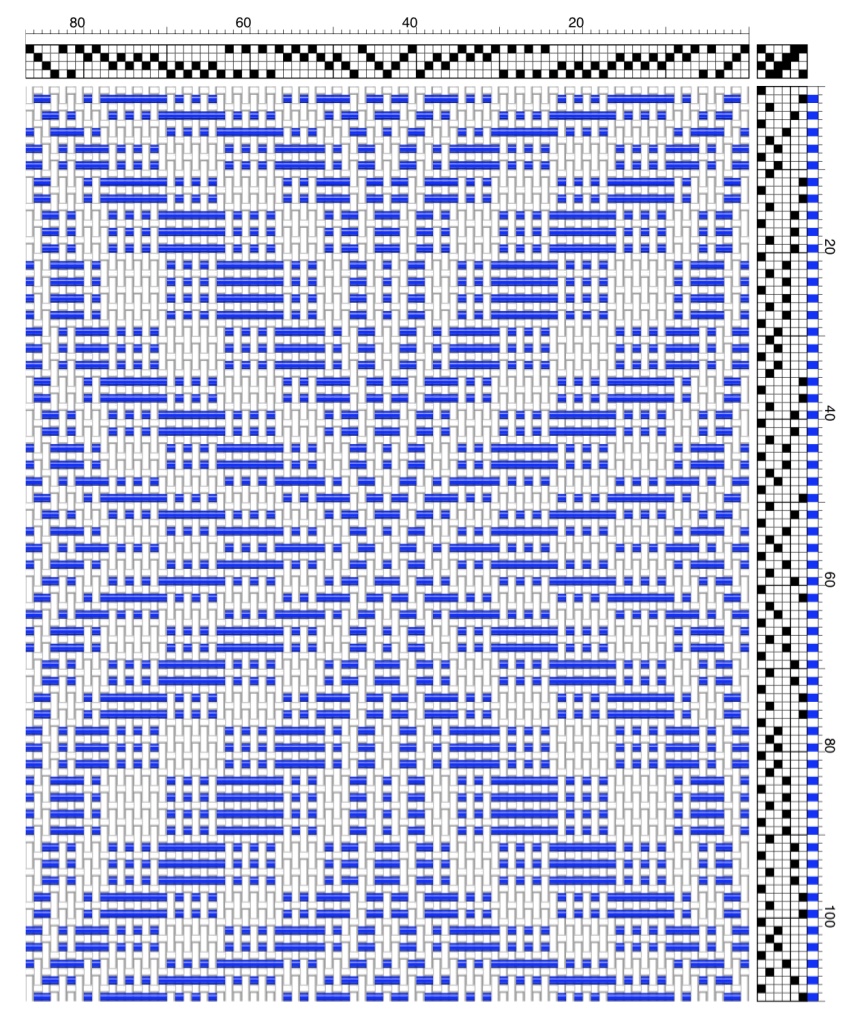

Overshot drafting formats: Figure 1 is from Davison’s A Handweaver’s Source Book, Figure 2 is from Weaver Rose, and Figure 3 is from Wilson and Kennedy’s Of Coverlets.

Figures 1–3 show the most common early drafting methods. (Compare their length with the thread-by-thread version in Figure 5.) In shorthand drafts, each overshot block contains an even number of threads, four per block in these. (Block labels in red are added to Figures 1, 2, and 3 for clarity.) In Figure 1, from Marguerite Davison’s A Handweaver’s Source Book, the numbers tell how many times to thread each block; the rows tell which block to thread (A = 1-2, B = 3-2, C = 3-4, and D = 1-4). Note how the blocks always start on an odd shaft to preserve the even/odd sequence across the warp. The first column of numbers on the right (2/2) means to thread Block A (shafts 1-2) two times, then thread Block B (shafts 3-2) two times, etc.

In Figure 2, the method used by Weaver Rose, the lines represent the shafts. The numbers represent the order in which to thread the shafts. Reading from the right: Thread shaft 1, 2, 1, 2 for Block A. Then, moving to Block B, thread 3, 2, 3, 2, etc. In Figure 3, from Of Coverlets, the pair of shafts for each block is given with the number of times to thread it. Reading from the right: Thread 1-2, 2x; 3-2, 2x; 3-4, 2x, 1-4, 2x, etc. Figure 4 shows the actual thread-by thread draft for Figures 1–3. It also shows the way this threading would appear in Keep Me Warm One Night. In the drafts in this book, each block is threaded with an even number of threads and circled.

Figure 4: Dorothy and Harold Burnham’s Keep Me Warm One Night. Figure 5: Threading draft derived from Figures 1–4 with blocks circled. Figure 6: Balancing the draft. Figure 7: The balanced draft.

However, in overshot, blocks share shafts. That is, Block A (on shafts 1-2) shares shaft 2 with Block B and shaft 1 with Block D. Block B shares shaft 2 with Block A and shaft 3 with Block C, etc. When, for example, Block B is woven, a pattern-weft float covers the four threads that have been threaded for Block B and the thread on shaft 2 in Block A and the thread on shaft 3 in Block C. The circled blocks in Figure 5 show the warp threads that will actually produce pattern in each block using the drafts in Figures 1–4. Notice that Block B on the right will show a weft float over six threads, but on the left over only four. The same imbalance occurs with Block C; see also the drawdown in Figure 8. In the drafts derived from these shorthand drafts, float lengths over blocks in symmetrical positions always differ from each other by two warp threads.

Unbalanced drafts can be balanced by removing (or adding) pairs of shafts from the circled blocks; see Figures 6–10. In fact, to reduce or enlarge any draft, first circle the blocks so that they overlap to include their shared threads as in Figure 5. Then add or subtract pairs of threads. Notice that Block D has an odd number of threads, which is true of all “turning” blocks. Turning blocks are blocks where threading direction changes (any shift from the ABCD direction to the DCBA direction or vice versa).

The overshot drafts in Marguerite Davison’s A Handweaver’s Pattern Book and in Mary Meigs Atwater’s The Shuttle-Craft Book of American Hand-Weaving have all been balanced; see their drafting formats in Figures 11 and 12.

This project was really popular when I posted it on Instagram, so I thought I would share it here also. It is a simple overshot pattern - with a twist. Also a great way to show off some special yarn. The yarn I used for my pattern was a skein of hand spun camel/silk blend. I wove the fabric on my Jack loom but you could also use your four or eight shaft loom.

Overshot is a weave structure where the weft threads jump over several warp threads at once, a supplementary weft creating patterns over a plain weave base. Overshot gained popularity in the turn of the 19th century (although its origins are a few hundred years earlier than that!). Coverlets (bed covers) were woven in Overshot with a cotton (or linen) plain weave base and a wool supplementary weft for the pattern. The plain weave base gave structure and durability and the woollen pattern thread gave warmth and colour/design. Designs were basic geometric designs that were handed down in families and as it was woven on a four shaft loom the Overshot patterns were accessible to many. In theory if you removed all the pattern threads form your Overshot you would have a structurally sound piece of plain weave fabric.

I was first drawn to Overshot many years ago when I saw what looked to me like "fragments" of Overshot in Sharon Aldermans "Mastering Weave Structures".

I wanted to use my handspun - but I only had a 100gms skein, I wanted to maximise the amount of fabric I could get using the 100gms. I thought about all the drafts I could use that would show off the weft and settled on overshot because this showcases the pattern yarn very nicely. I decided to weave it “fragmented” so I could make my handspun yarn go further. I chose a honeysuckle draft.

When doing the treadle tie-up I used 3 and 8 for my plain weave and started weaving from the left, treadle 3 - so you always know which treadle you are up to - shuttle on the left - treadle 3, shuttle on the right treadle 8. I then tied up the pattern on treadles 4,5,6 and 7. You can work in that order by repeating the sequence or you can mix it up and go from 4 to 7 and back to 4 again etc. You will easily see what the pattern is doing.

Over 50 instructional videos that guide you through making a warp, dressing your loom, weaving, finishing your cloth, and troubleshooting. View product images for course outline.

There are lots of reasons why we are excited to be featuring crackle weave this spring! Crackle is an incredibly versatile style of weaving from a design perspective, allowing you to weave anything from intricate diamond patterns to chunky geometric shapes. But even though it can create some pretty fancy designs, crackle makes cloth that has substantial body and stands up to wear and tear. Crackle has us dreaming of beach towels, picnic blankets, decorative throws, and--of course--sewing up some beautiful tops from handwoven cloth.

Well, it has a reputation for being a little… complicated. But while the threading patterns can be pretty complex (often with dozens of ends in a pattern repeat) the wide range of treadling options mean you can set your own challenge level with crackle. Once you’ve tackled the threading, you might want to take on a treadling challenge like weaving the pattern as drawn in, or you might find using simple point twill treadling is more your speed. Either option will produce a beautiful result.

Crackle weave is a bit like a cross between overshot and summer-and-winter. Like both of these styles, crackle uses two wefts: a heavier pattern weft that shows off the design, and a thinner ground weft used to provide stability. And like overshot and summer-and-winter, crackle patterns are written by combining different patterns blocks (set threading repeats with specific rules).

What makes crackle distinct is that the threading blocks are made up of little point twill sequences. You’ve likely seen 4-shaft point twill, with the threading going 1-2-3-4-3-2-1. This is a common threading used to make zigzags and diamonds. Crackle uses the tie-up for 2/2 twill, but the point twill used for crackle is a little simpler. This is because crackle only uses three shafts at a time--for example, 1-2-3-2-1.

So here’s where it gets cool. On a four shaft loom, you can make four different 3-shaft point twill sequences. You can start on shaft one for 1-2-3-2, on shaft two for 2-3-4-3, on shaft three for 4-3-1-4, or on shaft four for 4-1-2-1. These are the building blocks of crackle weave.

You can repeat a block as many times as you want in a crackle threading. Whenever you move from one block to the next, close off the block by returning to the first thread in that block. So to move from Block A to Block B, you would wrap up Block A with a 1 before beginning Block B: 1-2-3-2-1-2-3-4-3. (Some weavers also simply eliminate the duplicate between the end of Block A and the beginning of Block B: 1-2-3-2-3-4-3. Either is fine! If you look at the drawdowns above you’ll see I used a mix of both strategies.)

Because crackle depends on smooth transitions between pattern blocks, you can’t just skip straight from say, Block A to Block C. Crackle patterns wander up and down and all over, but they only ever move one shaft at a time. They never skip a shaft. This ensures a stable cloth with small floats. So if you want to go from Block A to Block C you can still do it, but you need to connect them with extra threads called ‘incidentals’. The rule for crackle is this: every time you skip over a block, add the first thread of that block as an incidental. So to move from Block A to Block C, you would thread Block A (1-2-3-2), wrap up Block A by returning to its first thread (1), then add the incidental for Block B (2), before moving to Block C (3-4-1-4).

But if everything between my descriptions of pretty fields of diamonds and this part sounded like absolute nonsense, don’t worry! You can still enjoy weaving crackle! While many crackle project call for more complex treadling (treadling in blocks, as drawn in, as summer-and-winter, as overshot, or in pairs) this is not required. All of the fussy stuff goes into designing the threading. If you have a pattern that provides a threading, literally any standard twill treadling will work with any crackle pattern. You can do straight twill, point twill, extended point twill, advancing twill, rosepath, Ms & Ws, or even Wall of Troy treadling, and something beautiful will result! The only tricky part is remembering to add tabby (plain weave) picks with your ground weft in between each pick of your pattern.

Overshot: The earliest coverlets were woven using an overshot weave. There is a ground cloth of plain weave linen or cotton with a supplementary pattern weft, usually of dyed wool, added to create a geometric pattern based on simple combinations of blocks. The weaver creates the pattern by raising and lowering the pattern weft with treadles to create vibrant, reversible geometric patterns. Overshot coverlets could be woven domestically by men or women on simple four-shaft looms, and the craft persists to this day.

Summer-and-Winter: This structure is a type of overshot with strict rules about supplementary pattern weft float distances. The weft yarns float over no more than two warp yarns. This creates a denser fabric with a tighter weave. Summer-and-Winter is so named because one side of the coverlet features more wool than the other, thus giving the coverlet a summer side and a winter side. This structure may be an American invention. Its origins are somewhat mysterious, but it seems to have evolved out of a British weaving tradition.

Twill:Twill along with plain and satin weave is one of the three simple weave structures. Twill is created by repetition of a regular ratio of warp and weft floats, usually 1:2, 1:3, or 2:4. Twill weave is identifiable by the diagonal orientation of the weave structure. This diagonal can be reversed and combined to create herringbone and diamond effects in the weave.

Double Cloth: Usually associated with professional weavers, double cloth is formed from two plain weave fabrics that swap places with one another, interlocking the textile and creating the pattern. Coverlet weavers initially used German, geometric, block-weaving patterns to create decorative coverlets and ingrain carpeting. These coverlets contain twice the yarn and are twice as heavy as other coverlets.

Multi-harness/Star and Diamond: This group of coverlets is characterized not by the structure but by the intricacy of patterning. Usually executed in overshot, Beiderwand, or geometric double cloth, these coverlets were made almost all made in Eastern Pennsylvania by professional weavers on looms with between twelve and twenty-six shafts.

America’s earliest coverlets were woven in New England, usually in overshot patterns and by women working collectively to produce textiles for their own homes and for sale locally. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, Age of Homespun examines this pre-Revolutionary economy in which women shared labor, raw materials, and textile equipment to supplement family incomes. As the nineteenth century approached and textile mills emerged first in New England, new groups of European immigrant weavers would arrive in New England before moving westward to cheaper available land and spread industrialization to America’s rural interior.

Coverlet weavers were among some of the earliest European settler in the Northwest Territories. After helping to clear the land and establish agriculture, these weavers focused their attentions on establishing mills and weaving operations with local supplies, for local markets. This economic pattern helped introduce the American interior to an industrial economy. It also allowed the weaver to free himself and his family from traditional, less-favorable urban factory life. New land in Ohio and Indiana enticed weavers from the New York and Mid-Atlantic traditions to settle in the Northwest Territories. As a result, coverlets from this region hybridized, blending the fondness for color found in Pennsylvania coverlets with the refinement of design and Scottish influence of the New York coverlets.

Southern coverlets almost always tended to be woven in overshot patterns. Traditional hand-weaving also survived longest in the South. Southern Appalachian women were still weaving overshot coverlets at the turn of the twentieth century. These women and their coverlets helped in inspire a wave of Settlement Schools and mail-order cottage industries throughout the Southern Appalachian region, inspiring and contributing to Colonial Revival design and the Handicraft Revival. Before the Civil War, enslaved labor was often used in the production of Southern coverlets, both to grow and process the raw materials, and to transform those materials into a finished product.

Because so many coverlets have been passed down as family heirlooms, retaining documentation on their maker or users, they provide a visual catalog of America’s path toward and response to industrialization. Coverlet weavers have sometimes been categorized as artisan weavers fighting to keep a traditional craft alive. New research, however, is showing that many of these weavers were on the forefront of industry in rural America. Many coverlet weavers began their American odyssey as immigrants, recruited from European textile factories—along with their families—to help establish industrial mills in America. Families saved their money, bought cheaper land in America’s rural interior and took their mechanical skills and ideas about industrial organization into the American heartland. Once there, these weavers found options. They could operate as weaver-farmers, own a small workshop, partner with a local carding mill, or open their own small, regional factories. They were quick to embrace new weaving technologies, including power looms, and frequently advertised in local newspapers. Coverlet weavers created small pockets of residentiary industry that relied on a steady flow of European-trained immigrants. These small factories remained successful until after the Civil War when the railroads made mass-produced, industrial goods more readily available nationwide.

This class is not for absolute beginner floor loom weavers. If you are a beginner, please start with my Introduction to Floor Loom Weaving class for all the basics.

A 4 shaft floor loom with 6 treadles. My floor loom has a 35" weaving width, but if your loom is smaller I have provided an alternative class project.

Kelly is a self taught weaver with a big passion for sharing the timeless art of weaving with others. Kelly is known for her calm and slow teaching style and she bases her classes on how she would have liked to have been taught. She designs all of her own projects and caters for levels from beginner to intermediate. Most available classes are for the rigid heddle loom, floor, table and inkle loom weaving.

This post is the third in a series introducing you to common weaving structures. We’ve already looked at plain weave and twill, and this time we’re going to dive into the magic of overshot weaves—a structure that’s very fun to make and creates exciting graphic patterns.

Overshot is a term commonly used to refer to a twill-based type of weaving structure. Perhaps more correctly termed "floatwork" (more on that later), these textiles have a distinctive construction made up of both a plain weave and pattern layer. Requiring two shuttles and at least four shafts, overshot textiles are built using two passes: one weaves a tabby layer and the other weaves a pattern layer, which overshoots or floats, above.

Readers in the United States and Canada may be familiar with overshot textiles through woven coverlets made by early Scottish and English settlers. Using this relatively simple technique, a local professional weaver with a four-shaft loom could easily make a near-infinite variety of equally beautiful and complex patterns. If you’d like to learn more about overshot coverlets and some of the traditions that settlers brought with them, please see my reading list at the bottom of this article!

As it is twill-based, overshot will be very familiar to 4 shaft weavers. It’s made up of a sequence of 2-thread repeats: 1-2, 2-3, 3-4, and 1-4. These sequences can be repeated any number of times to elongate and create lines, curves, and shapes. These 2-thread repeats are often referred to as blocks or threading repeats, IE: 1-2 = block 1/A, 2-3 = block 2/B.

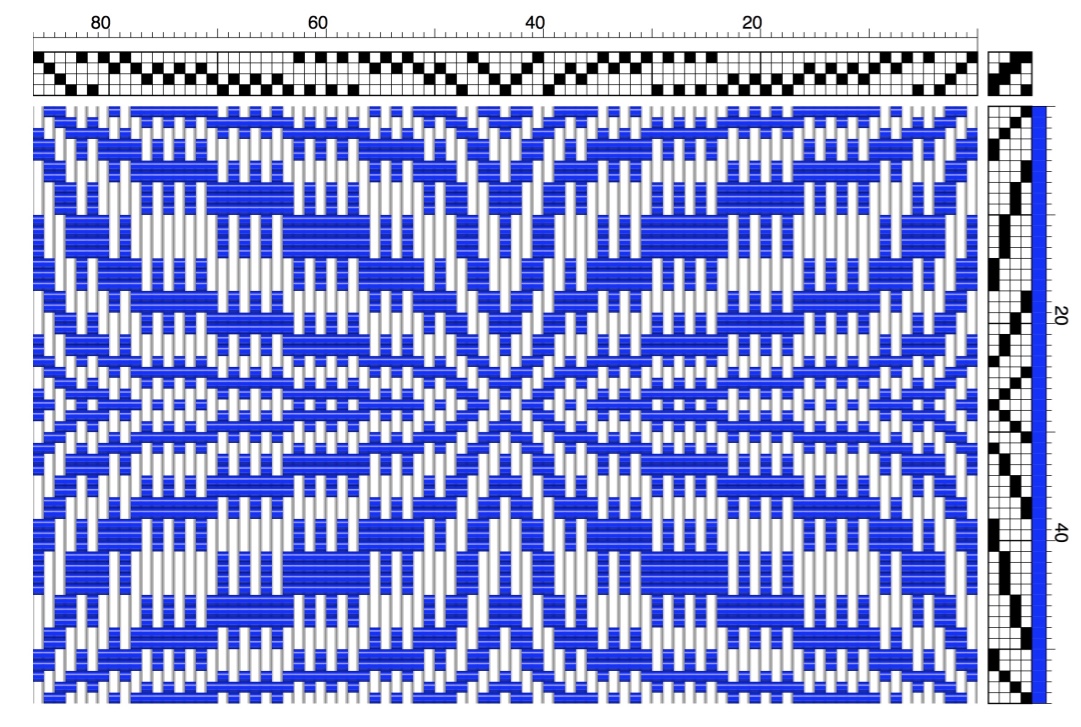

There are three ways weft appears on the face of an overshot cloth: as a solid, half-tone, or blank. In the draft image I’ve shared here, you can see an example of each—the solid is in circled in blue, the half-tone in red, and the blank yellow. Pressing down the first treadle (shafts 1 and 2), for example, creates solid tones everywhere there are threads on shafts 1 and 2, half-tones where there is a 1 or 2 paired with 3 or 4, and nothing on the opposite block, shafts 3 and 4. Of course, there’s not really nothing—the thread is simply traveling on the back of the cloth, creating a reverse of what’s on the face.

Because overshot sequences are always made up of alternating shafts, plain weave can be woven by tying two treadles to lift or lower shafts 1-3 and 2-4. When I weave two-shuttle weaves like overshot, I generally put my tabby treadles to the right and treadle my pattern picks with my left foot and my tabby with my right. In the draft image I’ve shared above, I’ve omitted the tabby picks to make the overarching pattern clearer and easier to read. Below is a draft image that includes the tabby picks to show the structure of the fabric.

Traditional overshot coverlets used cotton or linen for warp and plain weave wefts, and wool pattern wefts—but there’s no rule saying you have to stick to that! In the two overshot patterns I’ve written for Gist, I used both Mallo and Beam as my pattern wefts.

In the Tidal Towels, a very simple overshot threading creates an undulating wave motif across the project. It’s easy and repetitive to thread, and since the overshot section is relatively short, it’s an easy way to get a feel for the technique.

The Bloom Table Squares are designed to introduce you to a slightly more complex threading—but in a short, easy-to-read motif. When I was a new weaver, one of the most challenging things was reading and keeping track of overshot threading and treadling—but I’ve tried to make it easy to practice through this narrow and quick project.

Overshot works best with a pattern weft that 2-4 times larger than your plain weave ground, but I haven’t always followed that rule, and I encourage you to sample and test your own wefts to see how they look! In the samples I wove for this article, I used 8/2 Un-Mercerized Cotton weaving yarn in Beige for my plain weave, and Duet in Rust, Mallo in Brick, and Beam in Blush for my pattern wefts.

The Bloom Table Squares are an excellent example of what weavers usually mean when they talk about traditional overshot or colonial overshot, but I prefer to use the term "floatwork" when talking about overshot. I learned this from the fantastic weaver and textile historian Deborah Livingston-Lowe of Upper Canada Weaving. Having researched the technique thoroughly for her MA thesis, Deborah found that the term "overshot" originated sometime in the 1930s and that historical records variably called these weaves "single coverlets’ or ‘shotover designs.’ Deborah settled on the term "floatwork" to speak about these textiles since it provides a more accurate description of what’s happening in the cloth, and it’s one that I’ve since adopted.

Long out of print, this fabulous book covers the Burnham’s extensive collection of early settler textiles from across Canada, including basic threading drafts and valuable information about professional weavers, tools, and history.

This book contains the collected drafts and work of Frances L. Goodrich, whose interest in coverlets was sparked when a neighbor gifted her one in the 1890s. Full of charming hand-painted drafts, this book offers a glimpse into North Carolina’s weaving traditions.

Amanda Ratajis an artist and weaver living and working in Hamilton, Ontario. She studied at the Ontario College of Art and Design University and has developed her contemporary craft practice through research-based projects, artist residencies, professional exhibitions, and lectures. Subscribe to herstudio newsletteror follow her onInstagramto learn about new weaving patterns, exhibitions, projects, and more.

8613371530291

8613371530291