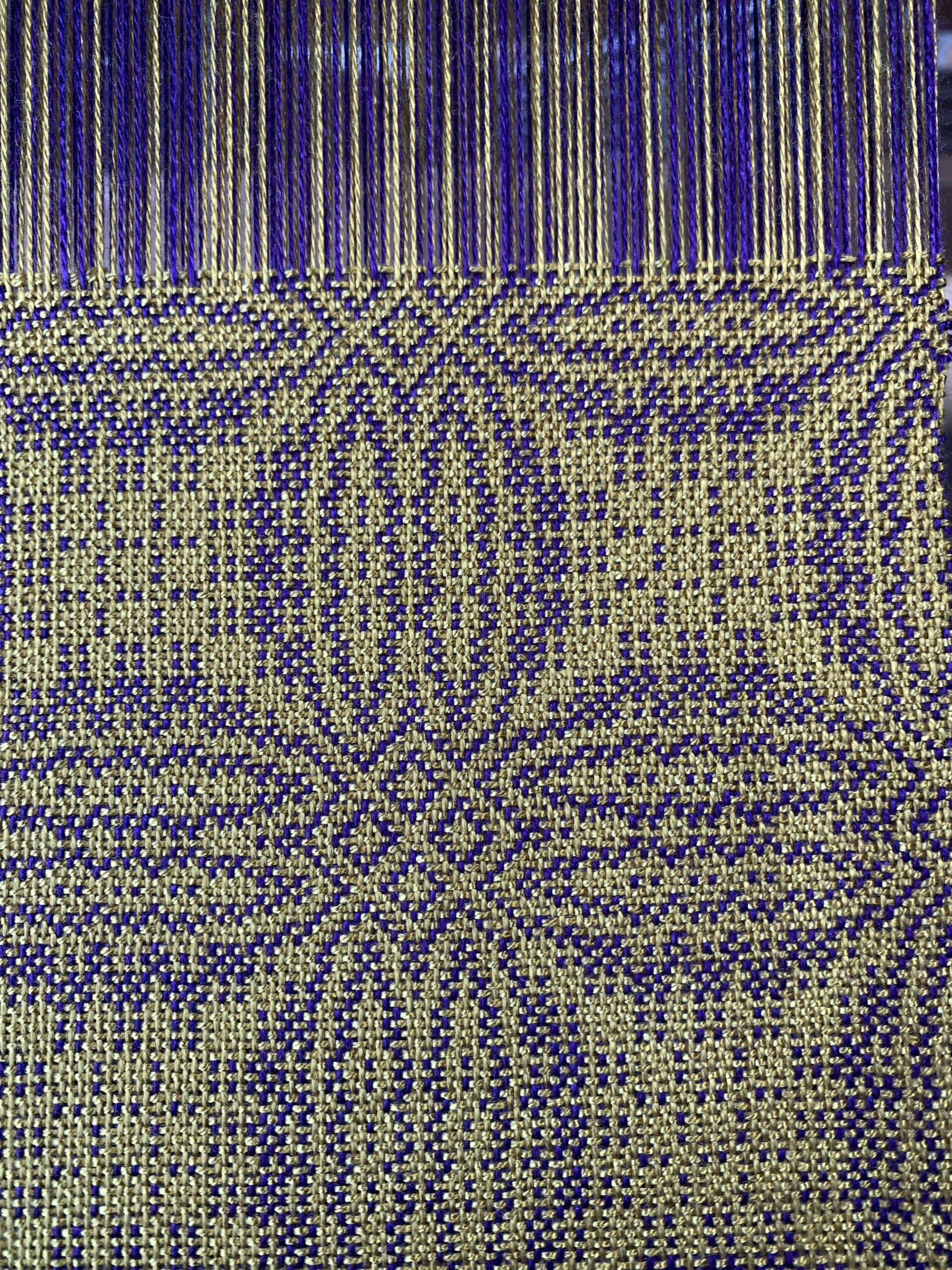

double weave overshot for sale

The weave structure is Colonial Double Weave, a 4-shaft system that allows you to weave a reversible double weave colonial overshot pattern without the weft floats of overshot. The threading starts with a basic overshot pattern, in this case, Blooming Leaf, found in many sources. This draft is on p. 133 in A Handweavers Pattern Book, by Marguerite Davison. The threading is then paralleled and warped and woven in two contrasting colors. This produces much more pattern than is usually obtainable without doing pick-up in a 4-shaft double weave fabric.

An old pattern in overshot weaving that has had many names over time: Muscadine Hills, Hickory Leaf, Blooming Leaf. The Double Bow Knot name comes from the leaf like square that forms the larger …

Overshot: The earliest coverlets were woven using an overshot weave. There is a ground cloth of plain weave linen or cotton with a supplementary pattern weft, usually of dyed wool, added to create a geometric pattern based on simple combinations of blocks. The weaver creates the pattern by raising and lowering the pattern weft with treadles to create vibrant, reversible geometric patterns. Overshot coverlets could be woven domestically by men or women on simple four-shaft looms, and the craft persists to this day.

Summer-and-Winter: This structure is a type of overshot with strict rules about supplementary pattern weft float distances. The weft yarns float over no more than two warp yarns. This creates a denser fabric with a tighter weave. Summer-and-Winter is so named because one side of the coverlet features more wool than the other, thus giving the coverlet a summer side and a winter side. This structure may be an American invention. Its origins are somewhat mysterious, but it seems to have evolved out of a British weaving tradition.

Twill:Twill along with plain and satin weave is one of the three simple weave structures. Twill is created by repetition of a regular ratio of warp and weft floats, usually 1:2, 1:3, or 2:4. Twill weave is identifiable by the diagonal orientation of the weave structure. This diagonal can be reversed and combined to create herringbone and diamond effects in the weave.

Double Cloth: Usually associated with professional weavers, double cloth is formed from two plain weave fabrics that swap places with one another, interlocking the textile and creating the pattern. Coverlet weavers initially used German, geometric, block-weaving patterns to create decorative coverlets and ingrain carpeting. These coverlets contain twice the yarn and are twice as heavy as other coverlets.

Beiderwand: Weavers in Northern Germany and Southern Denmark first used this structure in the seventeenth century to weave bed curtains and textiles for clothing. Beiderwand is an integrated structure, and the design alternates sections of warp-faced and weft-faced plain weave. Beiderwand coverlets can be either true Beiderwand or the more common tied-Beiderwand. This structure is identifiable by the ribbed appearance of the textile created by the addition of a supplementary binding warp.

Figured and Fancy: Although not a structure in its own right, Figured and Fancy coverlets can be identified by the appearance of curvilinear designs and woven inscriptions. Weavers could use a variety of technologies and structures to create them including, the cylinder loom, Jacquard mechanism, or weft-loop patterning. Figured and Fancy coverlets were the preferred style throughout much of the nineteenth century. Their manufacture was an important economic and industrial engine in rural America.

Multi-harness/Star and Diamond: This group of coverlets is characterized not by the structure but by the intricacy of patterning. Usually executed in overshot, Beiderwand, or geometric double cloth, these coverlets were made almost all made in Eastern Pennsylvania by professional weavers on looms with between twelve and twenty-six shafts.

America’s earliest coverlets were woven in New England, usually in overshot patterns and by women working collectively to produce textiles for their own homes and for sale locally. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, Age of Homespun examines this pre-Revolutionary economy in which women shared labor, raw materials, and textile equipment to supplement family incomes. As the nineteenth century approached and textile mills emerged first in New England, new groups of European immigrant weavers would arrive in New England before moving westward to cheaper available land and spread industrialization to America’s rural interior.

The coverlets from New York and New Jersey are among the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlets. NMAH possesses the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlet (dated 1817), made on Long Island by an unknown weaver. These coverlets are associated primarily with Scottish and Scots-Irish immigrant weavers who were recruited from Britain to provide a skilled workforce for America’s earliest woolen textile mills, and then established their own businesses. New York and New Jersey coverlets are primarily blue and white, double cloth and feature refined Neoclassical and Victorian motifs. Long Island and the Finger Lakes region of New York as well as Bergen County, New Jersey were major centers of coverlet production.

German immigrant weavers influenced the coverlets of Pennsylvania, Virginia (including West Virginia) and Maryland. Tied-Beiderwand was the structure preferred by most weavers. Horizontal color-banding, German folk motifs like the Distelfinken (thistle finch), and eight-point star and sunbursts are common. Pennsylvania and Mid-Atlantic coverlets tend to favor the inscribed cornerblock complete with weaver’s name, location, date, and customer. There were many regionalized woolen mills and factories throughout Pennsylvania. Most successful of these were Philip Schum and Sons in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and Chatham’s Run Factory, owned by John Rich and better known today as Woolrich Woolen Mills.

Coverlet weavers were among some of the earliest European settler in the Northwest Territories. After helping to clear the land and establish agriculture, these weavers focused their attentions on establishing mills and weaving operations with local supplies, for local markets. This economic pattern helped introduce the American interior to an industrial economy. It also allowed the weaver to free himself and his family from traditional, less-favorable urban factory life. New land in Ohio and Indiana enticed weavers from the New York and Mid-Atlantic traditions to settle in the Northwest Territories. As a result, coverlets from this region hybridized, blending the fondness for color found in Pennsylvania coverlets with the refinement of design and Scottish influence of the New York coverlets.

Southern coverlets almost always tended to be woven in overshot patterns. Traditional hand-weaving also survived longest in the South. Southern Appalachian women were still weaving overshot coverlets at the turn of the twentieth century. These women and their coverlets helped in inspire a wave of Settlement Schools and mail-order cottage industries throughout the Southern Appalachian region, inspiring and contributing to Colonial Revival design and the Handicraft Revival. Before the Civil War, enslaved labor was often used in the production of Southern coverlets, both to grow and process the raw materials, and to transform those materials into a finished product.

Because so many coverlets have been passed down as family heirlooms, retaining documentation on their maker or users, they provide a visual catalog of America’s path toward and response to industrialization. Coverlet weavers have sometimes been categorized as artisan weavers fighting to keep a traditional craft alive. New research, however, is showing that many of these weavers were on the forefront of industry in rural America. Many coverlet weavers began their American odyssey as immigrants, recruited from European textile factories—along with their families—to help establish industrial mills in America. Families saved their money, bought cheaper land in America’s rural interior and took their mechanical skills and ideas about industrial organization into the American heartland. Once there, these weavers found options. They could operate as weaver-farmers, own a small workshop, partner with a local carding mill, or open their own small, regional factories. They were quick to embrace new weaving technologies, including power looms, and frequently advertised in local newspapers. Coverlet weavers created small pockets of residentiary industry that relied on a steady flow of European-trained immigrants. These small factories remained successful until after the Civil War when the railroads made mass-produced, industrial goods more readily available nationwide.

I had the privilege of teaching in Washington state for 8 days in March this year. I found out how to pronounce names like Skagitt and Whatcom. I enjoyed meeting some fascinating weavers. I also experienced the wonderful community of weavers in the Puget Sound area, and of course I saw some lovely scenery.

My first teaching assignment was a lecture to the Whidbey Weavers Guild. During this time of emerging corona virus activity, the guild was well attended. My lecture on Overshot: Past and Present was a warm-up for the three-day workshop I would begin the following day.

We had an eager 15 attendees in the overshot workshop. The work was very creative. I send out instructions for preparing the looms ahead of time. In the workshop, everyone follows the same treadling order, but each weaver chooses their own colors to bring. Sometimes the thickness varies from one weaver to the next, also. The result is that everyone’s artistic decisions and sense of design are apparent. No two set of samples are identical. The students work through a certain set of treadling patterns and go home with a variety of samples. Some of their work is pictured below.

The day after my overshot workshop, two wonderful ladies took me up to my next assignment: a lecture on Summer and Winter to the Skagit Valley Weavers Guild. Many of the guild members were also members of Whidbey Weavers Guild and of the Whatcom Weavers Guild, who would host me for my next workshop. A couple of my overshot workshop students brought in their samples. They had cut them from the loom and washed them the day before, after the overshot workshop was finished. It was fun to see their completed work and talk about what their next steps would be.

The three-day Early American Textiles workshop was presented at the Jansen Art Center and hosted by the Whatcom Weavers Guild. Nine students wove round robin style on ten different looms. Each loom had been warped by one of the students in a traditional weaving pattern using thread similar to what early American weavers would have used. Throughout the workshop we stopped to talk about production practices within the US and Europe during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. One of the students brought in a lovely coverlet she had found in a thrift store. Another shared stories of her aunt and uncle who were weavers. My students were very knowledgeable and, as usual, I learned as much from them as they did from me.

The Whatcom group was a tight-knit community of weavers, too. Many have known each other for years and they constantly share ideas and encouragement. The Jansen Art Center provides studio space for their collection of looms as well as library and meeting space. The staff at the Jansen Center was very welcoming and the cafe served some dynamite lunches–plus afternoon lattes to keep us all going.

When I learned about overshot and designing for it, I wanted to try everything in my sampler. So, a different technique/design went into each of the four sections. The outside sections were similar 2-block overshot on 4 shafts.

8613371530291

8613371530291