free overshot weaving patterns manufacturer

This post is the third in a series introducing common weaving structures. We’ve already looked at plain weave and twill, and this time we’re going to dive into the magic of overshot weaves—a structure that’s very fun to make and creates exciting graphic patterns.

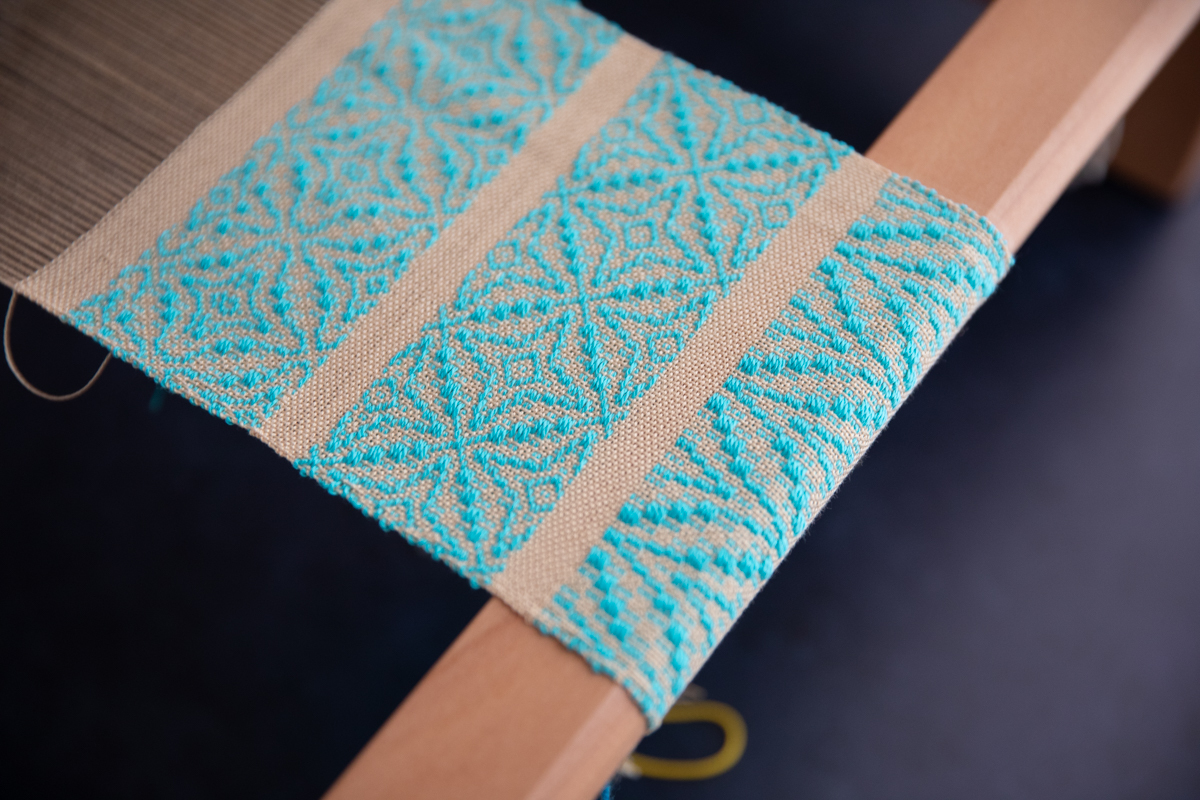

Woven by Rachel SnackWeave two overshot patterns with the same threading using this downloadable weave draft to guide you. This pattern features the original draft along with one pattern variation. Some yarns shown in the draft are available to purchase in our shop: 8/2 cotton, wool singles, 8/4 cotton (comparable to the 8/4 linen shown).

please note: this .pdf does not explain how to read a weaving draft, how to interpret the draft onto the loom, or the nuances of the overshot structure.

In the video, I mention learning how to weave Krokbragd. If you are interested in learning about this weaving technique, I encourage you to check out our course at the School of SweetGeorgia, Weaving Krokbragd, taught by Debby Greenlaw.

The overshot weaving project shown is woven on a 16″ Ashford Table Loom 8 shaft, The yarns used are Ashford 100% mercerised cotton in 10/2 and 5/2. (We don’t have this yarn currently listed on our site, but we’re able to order it in for you. Send us an email at: info@sweetgeorgiayarns.com!) The pattern is Overshot Sampler from the book Next Steps in Weaving by Pattie Graver

Many years ago, I finally got to try weaving. I took the Beginning to Weave workshop through the Ottawa guild. At that time, 1989, the OVWSG did not have a studio space to house what guild equipment we had acquired. (The Guild had an old second-hand 100 inch loom and 6 or 7 table looms. There may have been a floor loom too but I was distracted by the 100 inches of loom, so do not remember). All the looms lived in one of our guild members’ very big basements. On weekends, she either taught weaving workshops or hosted weavers working on the 100 inch loom. It sounded like a busy basement! I remember 4 weekends of driving to a little town just east of Ottawa. I took the table loom home each week to do homework. I still remember the sound of the mettle heddles rattling as I drove down the highway, back and forth to the classes. Then I think there were two more weekends of Intermediate weaving and Dona sent me off and I was weaving!

It all starts with yarn, wind it carefully, attach it to the back beam, wind on, thread the heddles, slay the reed, tie on to the front beam, check the tension and then start to weave. It sounds like a lot of work but it is all worth it as you start to pass the shuttle through the shed and the cloth begins to appear. Weaving was like Magic! From a pile of string to POOF, actual cloth!!!

During the workshop, I found pickup seemed strangely familiar as my brain watched my fingers happily lifting and twisting threads for the various lace and decorative weave patterns. The other thing that my brain went “ooh this is cool!” was Overshot. It is a weave structure that requires a ground and a pattern thread, (two shuttles). One is fine like the warp and the pattern thread is thicker and usually wool. I was still reacting to wool so I used cotton for both. My original goal was to draft and weave a Viking textile for myself but I put that aside for a moment, I will get back to that later.

The first thing I wove after my instruction was a present for my Mom. she had requested fabric to make a vest. I looked through A Handweaver’s Pattern Bookby Marguerite Porter Davison and found an overshot pattern that I thought we both would like. I wove it in two shades of blue (Mom’s favourite colour), at a looser thread count than usual. (Originally the overshot weave structure was used to make coverlets, so were tightly woven and a bit stiff, while I liked the pattern I wanted the fabric to be much more drapey.) Even worse, I did not want it to be as hard-edged in the pattern as it was originally intended so I tried a slub cotton as a test and loved it.

In the Exhibition The Inkle band, hanging beside the overshot, I wove much more recently. I used an Inkle loom and a supplemental warp thread. This means weaving with an extra separate thread that was not part of the main warp on the loom. I used a yarn with a fuzzy caterpillar-like slub.

You may be able to see how I wove the weird slubby supplemental warp. The yarn is weighted and left hanging over the back peg of the Inkle loom. It comes over the top peg (usually labelled B in diagrams) and floats above the weaving. In the areas where the Caterpillar (Slub) is not present I catch the yarn with the shuttle and weave it into the band. In the area the caterpillar appears I would leave the yarn above the warp and then start weaving it in again as I reached the end of the caterpillar. I hope that explanation doesn’t sound like mud and makes a bit of sense. Using a supplemental warp on an Inkle loom is not quite normal but it is a lot of fun.

I was going to tell you about my original goal in learning to weave, the mysterious Fragment #10 from a Viking excavation from around the year 1000, but I have likely confused you with weaving enough for one day. So I will save that for another chat. (don’t forget the Inkle loom I would like to tell you a bit more about that in another post too. I promise I will get back to felting in the not-too-distant future)

Who among us has not heard the siren call of fancy yarns, whether luscious silk or some hand-dyed or textured creation? My siren call came before I even learned to weave. Interweave’s Marilyn Murphy invited me to the 1996 Convergence conference, determined to get me hooked on weaving. In the Lunatic Fringe Yarns booth was a gorgous handpainted novelty warp, full of slub and ribbon yarns. I bought it and resolved then and there to become a weaver.

A few years later, I went to the Weavers’ School, wove some practice projects, and then warped up with that amazing novelty yarn, ready to weave a masterpiece. Unfortunately, I had somehow decided that the key to good selvedges was to crank up the warp tension until the loom groaned. “Zing!” went the ribbon yarns as they raveled. I also didn’t think about using a larger-dent reed to avoid abrasion. “Snap!” went the slub yarns as they caught and tore. I finished weaving the shawl only through the miracle of Fray Check (would that I had stock in that company), only to find that the stiff linen weft I had chosen made it more suitable for a dresser scarf than a garment. All in all, it was AFGE (another “fabulous” growing experience).

The January/February 2017 issue of Handwoven explores the possibilities of stress-free weaving with fancy yarns and the many ways they can kickstart our creativity. Tom Knisely brings us loads of fpractical tips and a charming scarf you’d never guess was huck, Deb Essen tells us how to turn a draft for thrifty novelty patterning, and Judith Shangold shares ideas for spectacular garment designs in simple cloth. Our fancy projects showcase the yarns, from Diane de Souza’s elegant white-on-white overshot scarf to Debbi Rutherford’s glowing name draft and Liz Moncrief’s satin bamboo towels. (Who would have thought?) I hope these projects inspire you to get fancy, too!

Overshot: The earliest coverlets were woven using an overshot weave. There is a ground cloth of plain weave linen or cotton with a supplementary pattern weft, usually of dyed wool, added to create a geometric pattern based on simple combinations of blocks. The weaver creates the pattern by raising and lowering the pattern weft with treadles to create vibrant, reversible geometric patterns. Overshot coverlets could be woven domestically by men or women on simple four-shaft looms, and the craft persists to this day.

Summer-and-Winter: This structure is a type of overshot with strict rules about supplementary pattern weft float distances. The weft yarns float over no more than two warp yarns. This creates a denser fabric with a tighter weave. Summer-and-Winter is so named because one side of the coverlet features more wool than the other, thus giving the coverlet a summer side and a winter side. This structure may be an American invention. Its origins are somewhat mysterious, but it seems to have evolved out of a British weaving tradition.

Double Cloth: Usually associated with professional weavers, double cloth is formed from two plain weave fabrics that swap places with one another, interlocking the textile and creating the pattern. Coverlet weavers initially used German, geometric, block-weaving patterns to create decorative coverlets and ingrain carpeting. These coverlets contain twice the yarn and are twice as heavy as other coverlets.

Multi-harness/Star and Diamond: This group of coverlets is characterized not by the structure but by the intricacy of patterning. Usually executed in overshot, Beiderwand, or geometric double cloth, these coverlets were made almost all made in Eastern Pennsylvania by professional weavers on looms with between twelve and twenty-six shafts.

America’s earliest coverlets were woven in New England, usually in overshot patterns and by women working collectively to produce textiles for their own homes and for sale locally. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, Age of Homespun examines this pre-Revolutionary economy in which women shared labor, raw materials, and textile equipment to supplement family incomes. As the nineteenth century approached and textile mills emerged first in New England, new groups of European immigrant weavers would arrive in New England before moving westward to cheaper available land and spread industrialization to America’s rural interior.

Coverlet weavers were among some of the earliest European settler in the Northwest Territories. After helping to clear the land and establish agriculture, these weavers focused their attentions on establishing mills and weaving operations with local supplies, for local markets. This economic pattern helped introduce the American interior to an industrial economy. It also allowed the weaver to free himself and his family from traditional, less-favorable urban factory life. New land in Ohio and Indiana enticed weavers from the New York and Mid-Atlantic traditions to settle in the Northwest Territories. As a result, coverlets from this region hybridized, blending the fondness for color found in Pennsylvania coverlets with the refinement of design and Scottish influence of the New York coverlets.

Southern coverlets almost always tended to be woven in overshot patterns. Traditional hand-weaving also survived longest in the South. Southern Appalachian women were still weaving overshot coverlets at the turn of the twentieth century. These women and their coverlets helped in inspire a wave of Settlement Schools and mail-order cottage industries throughout the Southern Appalachian region, inspiring and contributing to Colonial Revival design and the Handicraft Revival. Before the Civil War, enslaved labor was often used in the production of Southern coverlets, both to grow and process the raw materials, and to transform those materials into a finished product.

Because so many coverlets have been passed down as family heirlooms, retaining documentation on their maker or users, they provide a visual catalog of America’s path toward and response to industrialization. Coverlet weavers have sometimes been categorized as artisan weavers fighting to keep a traditional craft alive. New research, however, is showing that many of these weavers were on the forefront of industry in rural America. Many coverlet weavers began their American odyssey as immigrants, recruited from European textile factories—along with their families—to help establish industrial mills in America. Families saved their money, bought cheaper land in America’s rural interior and took their mechanical skills and ideas about industrial organization into the American heartland. Once there, these weavers found options. They could operate as weaver-farmers, own a small workshop, partner with a local carding mill, or open their own small, regional factories. They were quick to embrace new weaving technologies, including power looms, and frequently advertised in local newspapers. Coverlet weavers created small pockets of residentiary industry that relied on a steady flow of European-trained immigrants. These small factories remained successful until after the Civil War when the railroads made mass-produced, industrial goods more readily available nationwide.

Or, you can always call us to help you select the right combo for you! toll-free 1.888.383.7455 (silk) When you order yarn, please let us know it"s for this draft--we"ll make certain you get a 95g or larger skein.

These scarves are near-and-dear to my heart--this was on my loom in 2011 when I learned that Treenway Silks company was for sale. I thought it fortuitous that I was weaving with Treenway Silks--and we are honored that the founders, Karen & Terry, chose us to become the new owners. This draft has added a little border along the selvedges to add a bit of spice--I wish I"d have thought of this while weaving my scarves.

Adapted from Hand weaving patterns from Finland by HelViivi Merisalo; p28 #57 (turned), we find this kit especially fun as there is a different treadling for each of the two scarves.

Robin Wilton created this versatile silk scarves design. You can use Alirio-Thinner (20/2 noil, in Blue & Black(lead photo)or Kiku (20/2 silk, Creole Spice & Cantaloupe...photo in the free draft)

By alternating two colors in the warp, then weaving one scarf with one warp color and the second scarf with the other warp color, you get two different looks.

Or, you can always call us to help you select the right combo for you! toll-free 1.888.383.7455 (silk) When you order yarn, please let us know it"s for this draft--we"ll make certain you get a 95g or larger skein.

Try our ‘Glittering Diamonds’ Shadow Weave Scarves. Weave 2 fabulous scarves with 2 skeins of our most popular silk yarn, Kiku (100% Bombyx Spun Silk, 20/2).This 2-shuttle weave can produce two different looks--it just depends on which color you start your weaving with!What a perfect gift for someone special!

8613371530291

8613371530291