miniature overshot patterns for hand weaving supplier

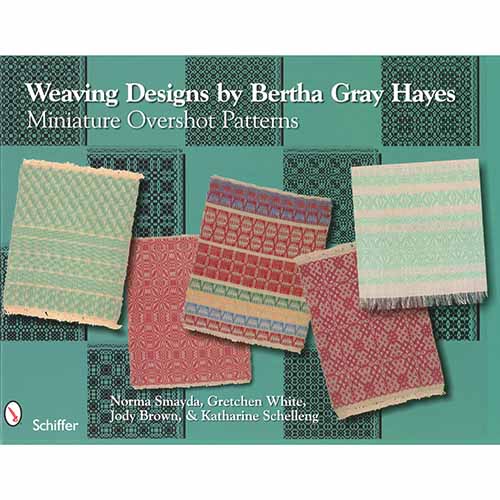

This book features the original sample collection and handwritten drafts of the talented, early 20th century weaver, Bertha Gray Hayes of Providence, Rhode Island. She designed and wove miniature overshot patterns for four-harness looms that are creative and unique. The book contains color reproductions of 72 original sample cards and 20 recently discovered patterns, many shown with a picture of the woven sample, and each with computer-generated drawdowns and drafting patterns.

Her designs are unique in their asymmetry and personal in her use of name drafting to create the designs. Bertha Hayes attended the first nine National Conferences of American Handweavers (1938-1946). She learned to weave by herself through the Shuttle-Craft home course and was a charter member of the Shuttle-Craft Guild, and authored articles on weaving.

About the authors: The Weavers" Guild of Rhode Island was founded in 1947 to promote understanding and the practice of handweaving. It offers monthly programs and workshops, and is an active member of the New England Weavers Seminar.

This volume is rooted in the weaving explorations of Bertha Gray Hayes, an early 20th century weaver from Providence, Rhode Island. Collected here are her unique miniature 4-shaft overshot patterns with computer-generated drafts. You’ll learn much about the history of American hand weaving, as well as the remarkable work of a single weaver, with her plentiful legacy of overshot patterns.

By Norma Smayda, Gretchen White, Jody Brown, and Katharine Schelleng. These four weavers have assembled the sample collection of miniature overshot patterns for four harness looms created in the early 20th century by Bertha Gray Hayes. The book contains color reproductions and computer-generated drawdowns for 92 designs. These differ from traditional overshot designs in that they are often based on name drafts and many are not woven "as drawn in", giving many of them a dynamic, asymmetrical style.

This book features the original sample collection and handwritten drafts of the talented, early 20th century weaver, Bertha Gray Hayes of Providence, Rhode Island. She designed and wove miniature overshot patterns for four-harness looms that are creative and unique. The book contains color reproductions of 72 original sample cards and 20 recently discovered patterns, many shown with a picture of the woven sample, and each with computer-generated drawdowns and drafting patterns. Her designs are unique in their asymmetry and personal in her use of name drafting to create the designs.

Bertha Hayes attended the first nine National Conferences of American Handweavers (1938-1946). She learned to weave by herself through the Shuttle-Craft home course and was a charter member of the Shuttle-Craft Guild, and authored articles on weaving.

*Estimated delivery dates- opens in a new window or tabinclude seller"s handling time, origin ZIP Code, destination ZIP Code and time of acceptance and will depend on shipping service selected and receipt of cleared payment. Delivery times may vary, especially during peak periods.Notes - Delivery *Estimated delivery dates include seller"s handling time, origin ZIP Code, destination ZIP Code and time of acceptance and will depend on shipping service selected and receipt of cleared payment. Delivery times may vary, especially during peak periods.

This book features the original sample collection and handwritten drafts of the talented, early 20th century weaver, Bertha Gray Hayes of Providence, Rhode Island. She designed and wove miniature overshot patterns for four-harness looms that are creative and unique. The book contains color reproductions of 72 original sample cards and 20 recently discovered patterns, many shown with a picture of the woven sample, and each with computer-generated drawdowns and drafting patterns. Her designs are unique in their asymmetry and personal in her use of name drafting to create the designs.

Bertha Hayes attended the first nine National Conferences of American Handweavers (1938-1946). She learned to weave by herself through the Shuttle-Craft home course and was a charter member of the Shuttle-Craft Guild, and authored articles on weaving.

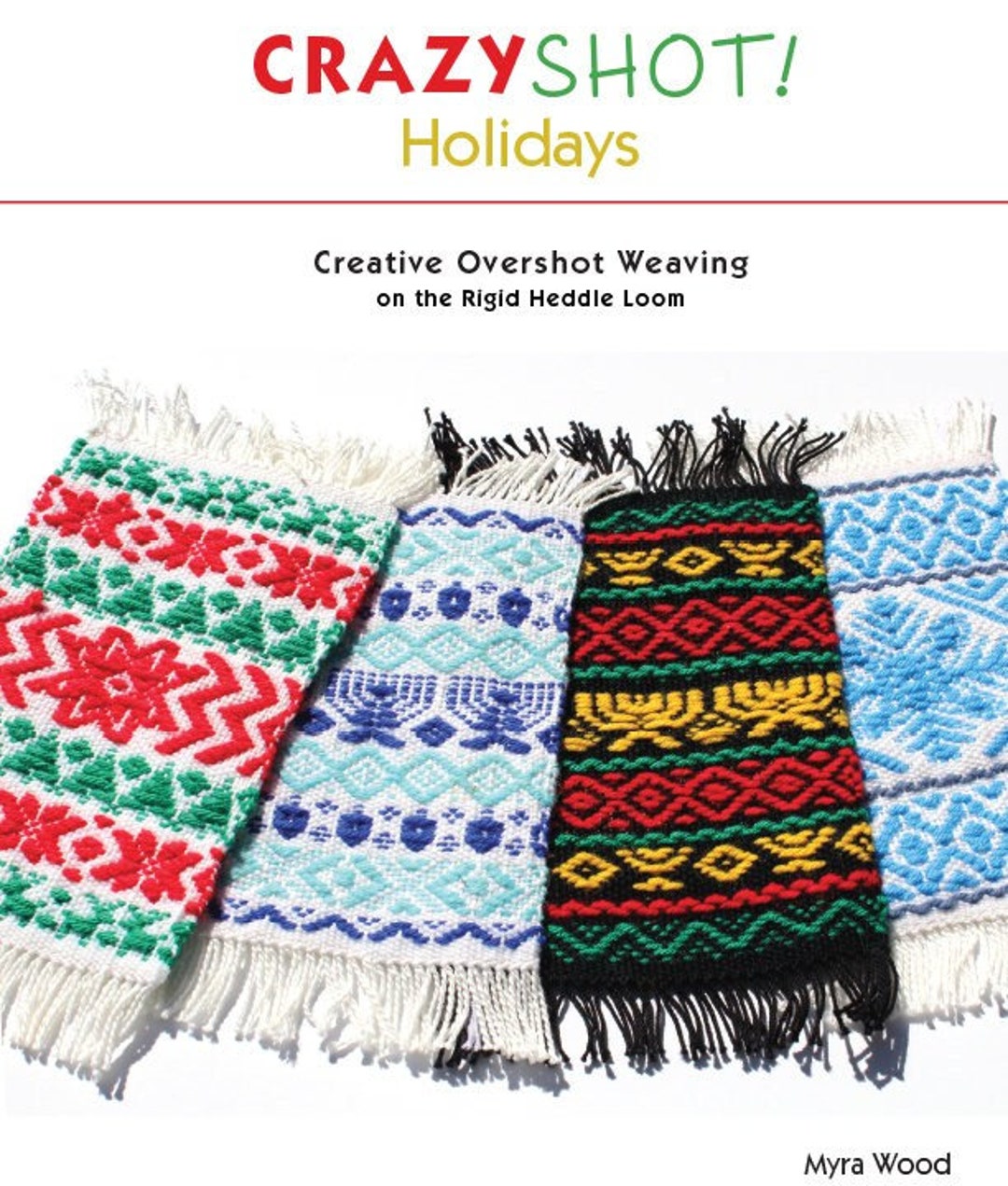

After weaving the project samples for my book, I had a bit of an 8/4 cotton warp remaining on the loom. I perused my stack of Handwoven magazines and saved project files for some inspiration and decided upon weaving a little overshot on this remnant.

For the Non-Weavers - Overshot is a weaving technique. If you are familiar with Colonial coverlets, they were traditionally woven in overshot patterns. Here is a link with great photos Woven American Coverlets.

Unlike Krokbragd, a wealth of information exists on how to weave overshot. Just about any weaving book will contain at least a chapter on the topic, as well as there are videos, articles and countless published drafts.

Back to my little overshot project, I found my inspiration in the November/December 2017 issue of Handwovenin an article by Inga Marie Carmel entitled ‘Exploring Overshot’. The author chose a draft called Blossom, a Bertha Gray Hayes miniature overshot pattern.

Bertha Gray Hayes was an early 20th century weaver known for her miniature overshot and name draft designs. Miniature overshot pares down an established overshot pattern to its bare minimum while still maintaining the integrity of the pattern’s character. For more on the subject, check out Weaving Designs By Bertha Gray Hayes: Miniature Overshot Patterns by Norma Smayda, Gretchen White, Jody Brown, and Katharine Schelleng.

In Ms. Carmel’s sampler, she explored six different treadlings of the Blossom pattern. Since I had a much smaller warp, I had to do a bit of reworking in Weaveit (the weaving software program I use). I was only able to weave three of the six variations; the star and rose which are two of the basic overshot treadlings, and a variation referred to as “in the Scandinavian manner”.

Typical of overshot samplers and coverlets, the motifs are framed by a complementary border. If you compare my left selvedge with the right, you will notice that I did not quite work out the correct border. Although I’m not keen to sample, this certainly is a good example where sampling would be beneficial before committing to weaving the edited draft on a much larger project.

An interesting feature of overshot is that the reverse side is generally also equally attractive. I actually chose this reverse side as the “front” of my project.

As I said at the beginning of the post, the warp is 8/4 cotton, as is the tabby weft. The pattern weft is Borg’s 6/2 Tuna wool in the color Denim. I had to add a couple of ends to my warp for a total of 107 ends at 15 EPI (sleyed 2-1 in 10-dent reed). I used my typical method of throwing a few picks of fusible thread (see this post) as I planned to do a hemmed finish. In the end, I hemmed just one end and left the other to fringe. I wet finished the little piece of fabric and when it was almost dry, gave it a hard press.

To make my mini pouch, I folded the fabric and whipstitched the sides (no turned seam). I didn’t like the fringe, so I trimmed close to the fused thread and the cotton fuzzed into a cute edge. The finished size is 6 1/4” x 4 1/2” (folded); the perfect size for my reading glasses or phone. See that little button . . .

Ordinarily items that have been woven since the previous NEWS (that is, in the previous 2 years) are permitted to be entered in the juried shows. Because of the special circumstances this year, that rule will be waived for 2023, and items woven since 2019 will be allowed in the juried shows in 2023. However, any item included in the 2021 photo gallery will not be allowed to be entered in the juried shows in 2023. Weavers should be aware of this as they may want to save their “best” item for 2023.

We are excited to announce the formation of The Rhode Island Weaving Center (RIWC), a non-profit educational center dedicated to handweaving. After years of long waitlists and an elevated interest in handweaving, Norma Smayda of the Saunderstown Weaving School and a board of local, talented weavers will open a weaving center with looms for classes, studio spaces, and a weaving library. The initial space will be smaller with hopes of expanding within a decade to have more looms, larger rooms, lectures and workshops, and possibly a meeting room for The Weavers Guild of Rhode Island. The RIWC will aim to provide the same individualized, specialized instruction Norma has provided for the last 45 years. The RIWC and the SWS will operate concurrently with the center eventually acquiring the school"s extensive weaving library, supplies, and looms. The RIWC will celebrate Norma’s dedication to handweaving and continue Rhode Island’s rich history of textile arts.

2020 update about Weaving Designs by Bertha Gray Hayes, or Bertha as we fondly call her: It has impressed the four authors with how popular this book has been, and continues to be. Partly this is witnessed by the royalties from sales that the Weavers Guild of RI receives biannually.

Even more interesting has been the number of letters we receive from weavers across the US and beyond. Often the weaver will include a sample of her weaving, and once a kitchen towel, as thanks for writing this book. Also we frequently see the book referenced in articles in the weaving journals.

The most surprising occurrence happened a year ago. I received an email from a woman in Maine who had a used table loom I might want. She had tried to give it away in Maine, but no one was interested. My first impulse was to say thank you but I had no room in the school for another loom. Then I read her email more closely. She is the great granddaughter of Mrs. MacAllister, who was a good friend of Bertha’s. We quoted Mrs. MacAllister several times in our book.

So we set a date for her to deliver the loom. She and her sister arrived with the loom and a few boxes of assorted weaving stuff, and we spent the better part of the morning sharing stories. They had a photograph we did not have, and we had one to give them. I have a sample book of weaving by Mrs. MacAllister, and they could point to some of the plaids and remember an uncle with a jacket made of that cloth woven by Mrs. MacAllister, etc.

Weaving rag rugs is an immensely satisfying process that enables you to use cast-off remnants of fabric - and a favorite old shirt or two - to make something beautiful and functional for your home. In this book, you"ll explore the fascinating history of rag weaving, learn how to weave a basic rag rug, master some of the most popular traditional designs, and experiment with contemporary techniques for weaving and embellishing rugs. Filled with scores of colour photographs of rugs by more than 40 artists from around the world, this book is a delight for weavers and non-weavers alike.

Weaving with rags developed out of genuine necessity centuries ago, when cloth was so highly treasured that it was often unwoven in order to reuse the thread. Although fabric is now commonly available at very low cost, weaving rag rugs remains an especially satisfying process. Transforming fabric remnants and old articles of clothing into beautiful, functional rugs yields a wonderful feeling of accomplishment, and it instills a sense of connection with history and tradition.

The basics of rag rug weaving have remained the same over the years, but the materials, designs, weave patterns, and color combinations have changed significantly. Today"s weavers have access to an abundant array of warp and weft materials, with a wide variety of fiber content, color, and pattern. There are few-if any-limitations on what you might incorporate into your design: plastic shopping bags, bread wrappers, nylon stockings, and industrial castoffs have all been included.

In this book, you"ll find the old and the new, traditional designs and contemporary approaches. Starting with a basic, plain-weave rug, it describes the materials and tools you"ll need, how to prepare your warp and weft, how to dress the loom, and how to weave with a rag weft. Then you"ll learn how to make more complex designs: stripes and plaids, block patterns, reversible designs, inlay motifs, tufted weaves, and many other variations. Applications of surface design techniques, such as immersion dyeing, screen printing, and painting with textile inks, are also explored. In the chapter on design, you"ll be guided through the process of choosing colors and deciding upon compositions for your rugs. You"ll also find several options for finishing your rug, from traditional braided fringe to a crisp, clean Damascus edge.

Once you feel comfortable with the basic techniques, you"ll want to sample the rag rug projects. There are a dozen in total, ranging in style from a subtle gradation of stripes to a vibrant tapestry inlay. You"ll find seaside motifs and square blocks, pale pastels and brilliant jewel tones. There is even a double weaving project chenille "caterpillars" are woven first, and these become the weft in a wonderfully textured chair pad. Each project is described in complete detail and accompanied by a weaving draft.

Throughout the book are full-color photographs of works by more than 40 artists from a dozen countries around the world. These images, together with how-to photography and detailed illustrations, will instruct you and inspire you to sample new directions in your weaving. A fascinating history of rag weaving complements this glorious collection of contemporary rugs.

Overshot: The earliest coverlets were woven using an overshot weave. There is a ground cloth of plain weave linen or cotton with a supplementary pattern weft, usually of dyed wool, added to create a geometric pattern based on simple combinations of blocks. The weaver creates the pattern by raising and lowering the pattern weft with treadles to create vibrant, reversible geometric patterns. Overshot coverlets could be woven domestically by men or women on simple four-shaft looms, and the craft persists to this day.

Summer-and-Winter: This structure is a type of overshot with strict rules about supplementary pattern weft float distances. The weft yarns float over no more than two warp yarns. This creates a denser fabric with a tighter weave. Summer-and-Winter is so named because one side of the coverlet features more wool than the other, thus giving the coverlet a summer side and a winter side. This structure may be an American invention. Its origins are somewhat mysterious, but it seems to have evolved out of a British weaving tradition.

Double Cloth: Usually associated with professional weavers, double cloth is formed from two plain weave fabrics that swap places with one another, interlocking the textile and creating the pattern. Coverlet weavers initially used German, geometric, block-weaving patterns to create decorative coverlets and ingrain carpeting. These coverlets contain twice the yarn and are twice as heavy as other coverlets.

Beiderwand: Weavers in Northern Germany and Southern Denmark first used this structure in the seventeenth century to weave bed curtains and textiles for clothing. Beiderwand is an integrated structure, and the design alternates sections of warp-faced and weft-faced plain weave. Beiderwand coverlets can be either true Beiderwand or the more common tied-Beiderwand. This structure is identifiable by the ribbed appearance of the textile created by the addition of a supplementary binding warp.

Multi-harness/Star and Diamond: This group of coverlets is characterized not by the structure but by the intricacy of patterning. Usually executed in overshot, Beiderwand, or geometric double cloth, these coverlets were made almost all made in Eastern Pennsylvania by professional weavers on looms with between twelve and twenty-six shafts.

America’s earliest coverlets were woven in New England, usually in overshot patterns and by women working collectively to produce textiles for their own homes and for sale locally. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, Age of Homespun examines this pre-Revolutionary economy in which women shared labor, raw materials, and textile equipment to supplement family incomes. As the nineteenth century approached and textile mills emerged first in New England, new groups of European immigrant weavers would arrive in New England before moving westward to cheaper available land and spread industrialization to America’s rural interior.

The coverlets from New York and New Jersey are among the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlets. NMAH possesses the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlet (dated 1817), made on Long Island by an unknown weaver. These coverlets are associated primarily with Scottish and Scots-Irish immigrant weavers who were recruited from Britain to provide a skilled workforce for America’s earliest woolen textile mills, and then established their own businesses. New York and New Jersey coverlets are primarily blue and white, double cloth and feature refined Neoclassical and Victorian motifs. Long Island and the Finger Lakes region of New York as well as Bergen County, New Jersey were major centers of coverlet production.

Coverlet weavers were among some of the earliest European settler in the Northwest Territories. After helping to clear the land and establish agriculture, these weavers focused their attentions on establishing mills and weaving operations with local supplies, for local markets. This economic pattern helped introduce the American interior to an industrial economy. It also allowed the weaver to free himself and his family from traditional, less-favorable urban factory life. New land in Ohio and Indiana enticed weavers from the New York and Mid-Atlantic traditions to settle in the Northwest Territories. As a result, coverlets from this region hybridized, blending the fondness for color found in Pennsylvania coverlets with the refinement of design and Scottish influence of the New York coverlets.

Southern coverlets almost always tended to be woven in overshot patterns. Traditional hand-weaving also survived longest in the South. Southern Appalachian women were still weaving overshot coverlets at the turn of the twentieth century. These women and their coverlets helped in inspire a wave of Settlement Schools and mail-order cottage industries throughout the Southern Appalachian region, inspiring and contributing to Colonial Revival design and the Handicraft Revival. Before the Civil War, enslaved labor was often used in the production of Southern coverlets, both to grow and process the raw materials, and to transform those materials into a finished product.

Because so many coverlets have been passed down as family heirlooms, retaining documentation on their maker or users, they provide a visual catalog of America’s path toward and response to industrialization. Coverlet weavers have sometimes been categorized as artisan weavers fighting to keep a traditional craft alive. New research, however, is showing that many of these weavers were on the forefront of industry in rural America. Many coverlet weavers began their American odyssey as immigrants, recruited from European textile factories—along with their families—to help establish industrial mills in America. Families saved their money, bought cheaper land in America’s rural interior and took their mechanical skills and ideas about industrial organization into the American heartland. Once there, these weavers found options. They could operate as weaver-farmers, own a small workshop, partner with a local carding mill, or open their own small, regional factories. They were quick to embrace new weaving technologies, including power looms, and frequently advertised in local newspapers. Coverlet weavers created small pockets of residentiary industry that relied on a steady flow of European-trained immigrants. These small factories remained successful until after the Civil War when the railroads made mass-produced, industrial goods more readily available nationwide.

8613371530291

8613371530291