overshot coverlet patterns manufacturer

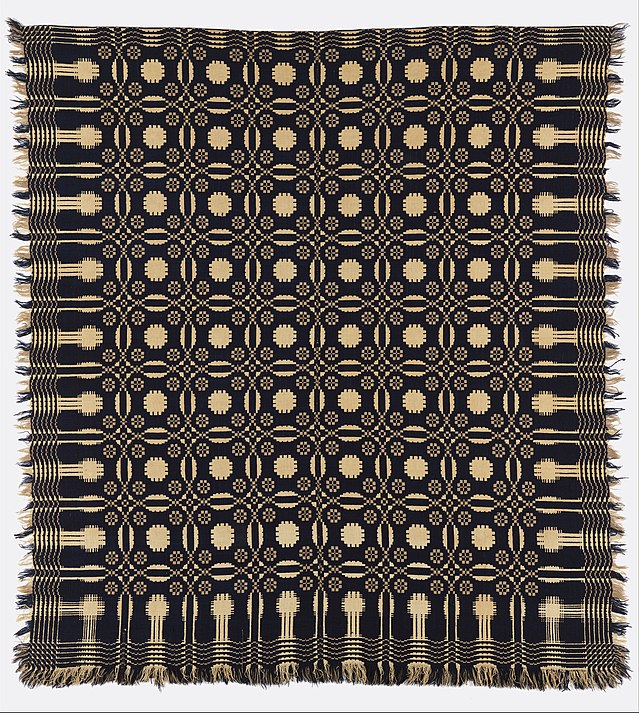

Overshot: The earliest coverlets were woven using an overshot weave. There is a ground cloth of plain weave linen or cotton with a supplementary pattern weft, usually of dyed wool, added to create a geometric pattern based on simple combinations of blocks. The weaver creates the pattern by raising and lowering the pattern weft with treadles to create vibrant, reversible geometric patterns. Overshot coverlets could be woven domestically by men or women on simple four-shaft looms, and the craft persists to this day.

Summer-and-Winter: This structure is a type of overshot with strict rules about supplementary pattern weft float distances. The weft yarns float over no more than two warp yarns. This creates a denser fabric with a tighter weave. Summer-and-Winter is so named because one side of the coverlet features more wool than the other, thus giving the coverlet a summer side and a winter side. This structure may be an American invention. Its origins are somewhat mysterious, but it seems to have evolved out of a British weaving tradition.

Double Cloth: Usually associated with professional weavers, double cloth is formed from two plain weave fabrics that swap places with one another, interlocking the textile and creating the pattern. Coverlet weavers initially used German, geometric, block-weaving patterns to create decorative coverlets and ingrain carpeting. These coverlets contain twice the yarn and are twice as heavy as other coverlets.

Beiderwand: Weavers in Northern Germany and Southern Denmark first used this structure in the seventeenth century to weave bed curtains and textiles for clothing. Beiderwand is an integrated structure, and the design alternates sections of warp-faced and weft-faced plain weave. Beiderwand coverlets can be either true Beiderwand or the more common tied-Beiderwand. This structure is identifiable by the ribbed appearance of the textile created by the addition of a supplementary binding warp.

Figured and Fancy: Although not a structure in its own right, Figured and Fancy coverlets can be identified by the appearance of curvilinear designs and woven inscriptions. Weavers could use a variety of technologies and structures to create them including, the cylinder loom, Jacquard mechanism, or weft-loop patterning. Figured and Fancy coverlets were the preferred style throughout much of the nineteenth century. Their manufacture was an important economic and industrial engine in rural America.

Multi-harness/Star and Diamond: This group of coverlets is characterized not by the structure but by the intricacy of patterning. Usually executed in overshot, Beiderwand, or geometric double cloth, these coverlets were made almost all made in Eastern Pennsylvania by professional weavers on looms with between twelve and twenty-six shafts.

America’s earliest coverlets were woven in New England, usually in overshot patterns and by women working collectively to produce textiles for their own homes and for sale locally. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, Age of Homespun examines this pre-Revolutionary economy in which women shared labor, raw materials, and textile equipment to supplement family incomes. As the nineteenth century approached and textile mills emerged first in New England, new groups of European immigrant weavers would arrive in New England before moving westward to cheaper available land and spread industrialization to America’s rural interior.

The coverlets from New York and New Jersey are among the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlets. NMAH possesses the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlet (dated 1817), made on Long Island by an unknown weaver. These coverlets are associated primarily with Scottish and Scots-Irish immigrant weavers who were recruited from Britain to provide a skilled workforce for America’s earliest woolen textile mills, and then established their own businesses. New York and New Jersey coverlets are primarily blue and white, double cloth and feature refined Neoclassical and Victorian motifs. Long Island and the Finger Lakes region of New York as well as Bergen County, New Jersey were major centers of coverlet production.

German immigrant weavers influenced the coverlets of Pennsylvania, Virginia (including West Virginia) and Maryland. Tied-Beiderwand was the structure preferred by most weavers. Horizontal color-banding, German folk motifs like the Distelfinken (thistle finch), and eight-point star and sunbursts are common. Pennsylvania and Mid-Atlantic coverlets tend to favor the inscribed cornerblock complete with weaver’s name, location, date, and customer. There were many regionalized woolen mills and factories throughout Pennsylvania. Most successful of these were Philip Schum and Sons in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and Chatham’s Run Factory, owned by John Rich and better known today as Woolrich Woolen Mills.

Coverlet weavers were among some of the earliest European settler in the Northwest Territories. After helping to clear the land and establish agriculture, these weavers focused their attentions on establishing mills and weaving operations with local supplies, for local markets. This economic pattern helped introduce the American interior to an industrial economy. It also allowed the weaver to free himself and his family from traditional, less-favorable urban factory life. New land in Ohio and Indiana enticed weavers from the New York and Mid-Atlantic traditions to settle in the Northwest Territories. As a result, coverlets from this region hybridized, blending the fondness for color found in Pennsylvania coverlets with the refinement of design and Scottish influence of the New York coverlets.

Southern coverlets almost always tended to be woven in overshot patterns. Traditional hand-weaving also survived longest in the South. Southern Appalachian women were still weaving overshot coverlets at the turn of the twentieth century. These women and their coverlets helped in inspire a wave of Settlement Schools and mail-order cottage industries throughout the Southern Appalachian region, inspiring and contributing to Colonial Revival design and the Handicraft Revival. Before the Civil War, enslaved labor was often used in the production of Southern coverlets, both to grow and process the raw materials, and to transform those materials into a finished product.

Because so many coverlets have been passed down as family heirlooms, retaining documentation on their maker or users, they provide a visual catalog of America’s path toward and response to industrialization. Coverlet weavers have sometimes been categorized as artisan weavers fighting to keep a traditional craft alive. New research, however, is showing that many of these weavers were on the forefront of industry in rural America. Many coverlet weavers began their American odyssey as immigrants, recruited from European textile factories—along with their families—to help establish industrial mills in America. Families saved their money, bought cheaper land in America’s rural interior and took their mechanical skills and ideas about industrial organization into the American heartland. Once there, these weavers found options. They could operate as weaver-farmers, own a small workshop, partner with a local carding mill, or open their own small, regional factories. They were quick to embrace new weaving technologies, including power looms, and frequently advertised in local newspapers. Coverlet weavers created small pockets of residentiary industry that relied on a steady flow of European-trained immigrants. These small factories remained successful until after the Civil War when the railroads made mass-produced, industrial goods more readily available nationwide.

Description Weavers at the Lancaster Carpet, Coverlet, Quilt, and Yarn Manufactory, owned by Philip Schum likely wove this Jacquard, mauve, red, green, and brown, double-cloth coverlet sometime between 1856 and 1880. The centerfield features a large central medallion made up of concentric floral wreaths. Inside these medallions is a large representation of the United States Capitol. The centerfield ground is made up of shaded triangles. Each corner of the centerfield design features a bird surrounded by flowers and above the bird is a boteh, a motif found on Kashmiri shawls and later European copies commonly referred to as Paisley pattern. The four-sided border is composed of meandering floral and foliate designs. There are not traditional cornerblocks on this coverlet, but there are large floral or foliate medallions in each corner that are very similar to those used on signed Philip Schum coverlets. There is fringe along three sides. This coverlet was woven on a broadloom, and possibly a power loom.

Philip Schum (1814-1880) was born in Hesse-Darmstadt, Holy Roman Empire. He immigrated to New York, moving to Lancaster County, PA in approximately 1844. He was not trained as a weaver and there is no evidence that he ever was. What we do know is that Philip Schum was a savvy businessman. He worked first as a "Malt Tramper" in New York, a position presumably linked to brewing and malting of grains. After six months, Philip was able to afford to bring his first wife Ana Margartha Bond (1820-1875) to join him in Pennsylvania. Once reunited, Philip worked as a day laborer, shoemaker, and basket-maker. He purchased a small general store in Lancaster City in 1852. By 1856, he has built his business enough to sell at a profit and purchase the Lancaster Carpet, Coverlet, Quilt, and Yarn Manufactory. Philip"s first wife, Anna, passed away sometime before 1879, because in this year, Philip married his second wife, Anna Margaret Koch (1834-1880). The two were tragically killed in a train accident in 1880, when a locomotive stuck their horse and buggy. The New Era, a local Lancaster newspaper titled the article about the incident with the headline, "Death"s Harvest." Lancaster Carpet, Coverlet, Quilt, and Yarn Manufactory began with just one or two looms and four men. It grew to four looms and eight men quickly. By 1875, the factory had twenty looms and employed forty men. Philip Schum was no weaver. He was an entrepreneur and businessman who invested in the growing market for household textiles. Philip"s estate inventory included a carpet shop, weaving shop, dye house, two stores, and a coal yard. At the time of his death were also listed 390 "Half-wool coverlets." These were valued at $920. In 1878, Philip partnered with his son, John E. Schum to form, Philip Schum, Son, and Co. Another Schum coverlet is in the collections of the MFA-Houston. This particular coverlet was purchased by the donor"s grandfather in either Cincinnati or Pittsburg while he was serving as a ship"s carpenter along the Ohio River trade routes. The family would later settle in Crawford County, Indiana. This fact also shows that Philip Schum"s coverlets, quilts, yarn, etc. were not just being made for the local market. Schum was transporting his goods west and presumably in other directions. He was making for an American market.

I have always dreamed of weaving a coverlet with my merino wool. I have a copy of Of Coverlets and have envisaged weaving every last one of them. I had eyed the Cranbrook for years and schemed a plan of how to acquire just one more loom. The shop had a great space that called its name. I wanted to weave on this beautiful loom, as well as have it available for others who share the same dream.

We purchased the 60″ 8-shaft Cranbrook with 12 treadles, the sliding threading bench, the sectional warping beam, tension box, and spool rack. The instructions were amazing, and it was easy to set up. The tension box was essential during the beaming process. We only had one Schacht spool rack which only controlled 20 of our 40 cotton bobbins. We improvised “racks” for the remaining 20 bobbins, which we do not recommend. The threading bench is another accessory that helped us to complete the warping of this large project (getting a friend to sit there is also recommended). With the ease of the tension box, it made sense to warp a 30-yard warp. In this way, the warped loom would be available for commissions and studio hours for those weavers who wish to weave their own coverlet.

I chose Lee’s Surrender as my first project because it is the pattern shown on the “Of Coverlets” introductory page and I found it to be such an inspiration. I continue to dream of bringing the whole book to life through weaving the patterns one by one—even if I have to finish in the nursing home.

It was these woven bed coverings—variously called coverlets, coverlids, and “kivers”—that captured the imagination of collectors in the early 20th century. Unlike humble towels, sheets, and handkerchiefs, coverlets were likely to be treasured, preserved, and passed down through the generations. They used simple color combinations (usually white and indigo blue) and geometric patterns to produce striking effects that appealed to Americans who were tired of the ornate furnishings of the Victorian era. To many collectors, the coverlets were true works of art that demonstrated the innate aesthetic sense of early American women. They also served as tangible symbols of the industry and thrift associated with the “age of homespun.”

Coverlets were made on the same four-harness loom that was used to produce other kinds of cloth. As I noted in the last blog post, in its most basic form weaving involves only two sets of elements—the warp and the weft. In plain weaving, the weft yarn goes over one warp yarn, then under the next, and so on. In float weaves, there are also two sets of elements, but the weft goes over or under more than one warp. (Twill and satin are examples of float weaves.) Coverlets use a type of weave called overshot, which also uses floats but adds a third set of yarns to create a compound weave. There is a warp and weft of white cotton or linen and then a supplementary weft of colored wool, which “floats” over and under the warp to create the pattern. Since the width of a loom was limited to the span of the weaver’s arms, coverlets were woven in two halves and then sewn together down the middle.

Weavers shared overshot coverlet patterns with friends and family as drafts, a form of notation that recorded the way that threads were to be put through the heddles of the harnesses and the sequence of the treadles that controlled the harnesses. Drafts bear a certain resemblance to musical notation, with four horizontal lines representing the harnesses and numbers or other marks representing the threads. Each weaver had her own way of recording drafts which can seem quite mysterious to non-weavers. Like quilters, weavers also gave their coverlets fanciful names—Broken Snowballs, Lafayette’s Fancy, Wandering Vine—which varied by region. In a world of mass-produced goods, the individuality of coverlets and their makers was part of their charm to collectors.

The earliest American woven coverlet that can be definitively dated is from 1771, and women continued to make them into the 19th century, though by the 1820s professional weavers were also making more elaborate jacquard coverlets. As families moved west from New England into New York, Ohio, Indiana, and beyond, they brought the tradition of weaving coverlets with them. In certain parts of the south, particularly the mountain regions of Kentucky and Tennessee, domestic textile production remained an important part of the local economy well into the 1900s. In our next posts, we’ll look at early collectors of coverlets and their relationship with the movement to preserve hand weaving in Appalachia.

In addition to coverlets, the museum collections also include barn frame looms, spinning wheels, warping reels, hatchels and other textile production equipment as well as reference materials, original research, "period" weavers" journals, early pattern drafts and more.

The museum welcomes donations of interesting and unusual coverlets, research and reference materials and weaving equipment. Some notable collections, or portions of collections, gifted and permanently located at the museum include materials from:

*The founding collection, from Melinda & Laszlo Zongor, is featured in Coverlets at the Gilchrist: American Coverlets 1771-1889, an exhibition catalog published in 2005 and available at the museum. This collection includes the oldest known overshot coverlet to be dated in the weave (1771). Note: For folks new to coverlets, the Gilchrist catalog includes a special section devoted to coverlet "Basics," offering brief descriptions of figured and geometric coverlets, pattern types, origins and makers, weave structures and more.

The National Museum of the American Coverlet welcomes relationships with general interest museums, historical societies and other institutions that presently house coverlets.

8613371530291

8613371530291