overshot oil and gas made in china

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Tianhe Oil Group Co. Ltd. is a global group. We are specialized in the production of drilling tools, including R&D, production, selling, leasing, maintenance and services. Tianhe has 5 main businesses spread across the globe in more than 50 countries in the world.

Tianhe Oil Group management prioritize its people, technology, continuous improvement and building brand awareness. Our mission is to continuously strive innovation and improvement and expand our business in the oilfield. We increased the investment in technology research and development, always looking to provide our global customers with the best technical products and services.

Tianhe Oil Group strongly believes and promotes Total Quality Management, implements the ISO quality management system, HSE management system and API standards. Our manufacturing facilities are well equipped with four automated induction heat treatment lines and dozens of other types of heat treatment ovens and well furnaces (Box type, well type, carburizing heat treatment furnace) to ensure full coverage of heat treatment required by the different products.

So far, Tianhe Oil Group has established strong business relationships with over 200 international oil & gas companies in supporting the top 50 oil producing countries. For example, we have partnered with Schlumberger, Halliburton, Baker Hughes, Weatherford, Shell, NOV, etc.

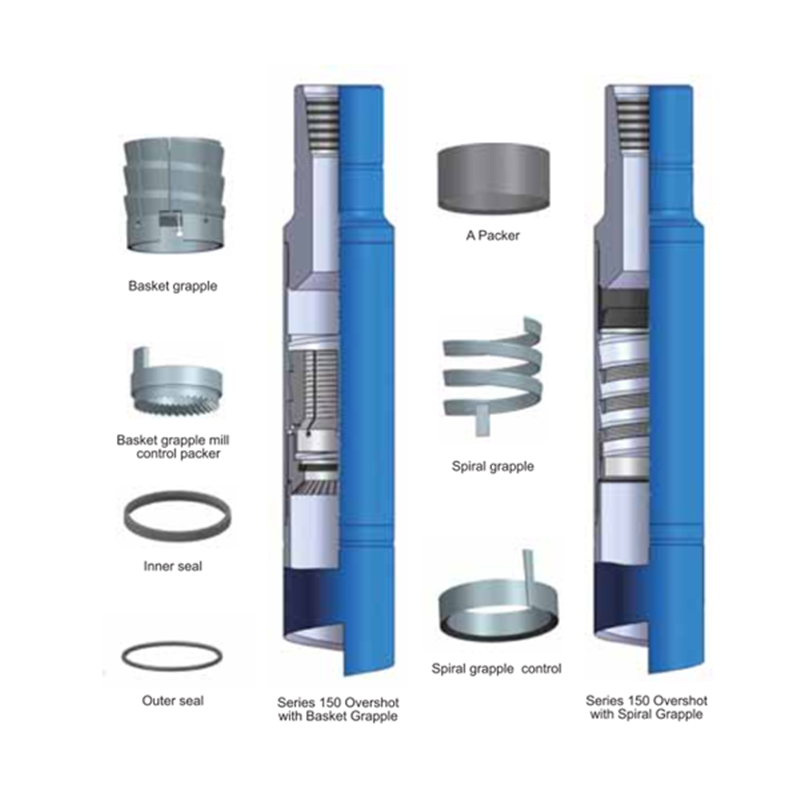

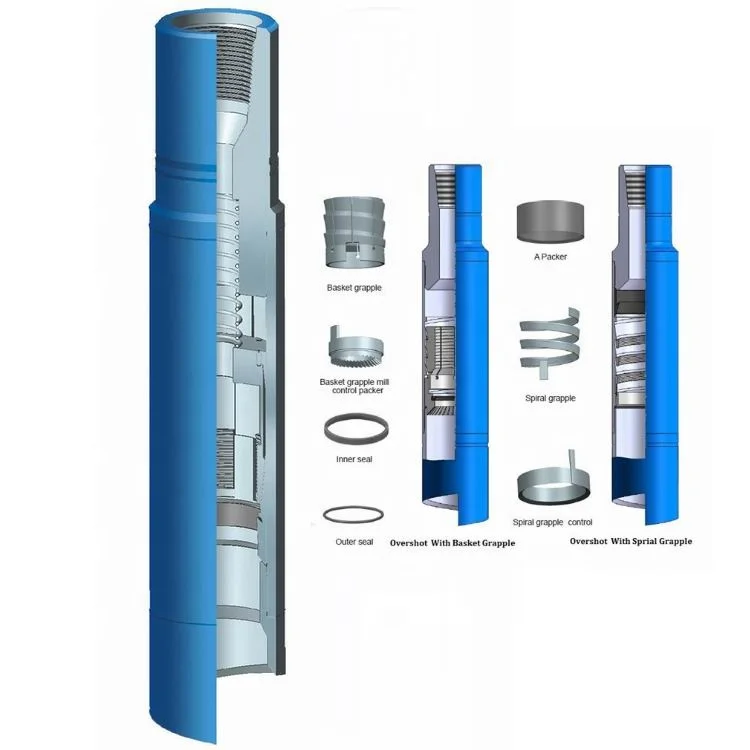

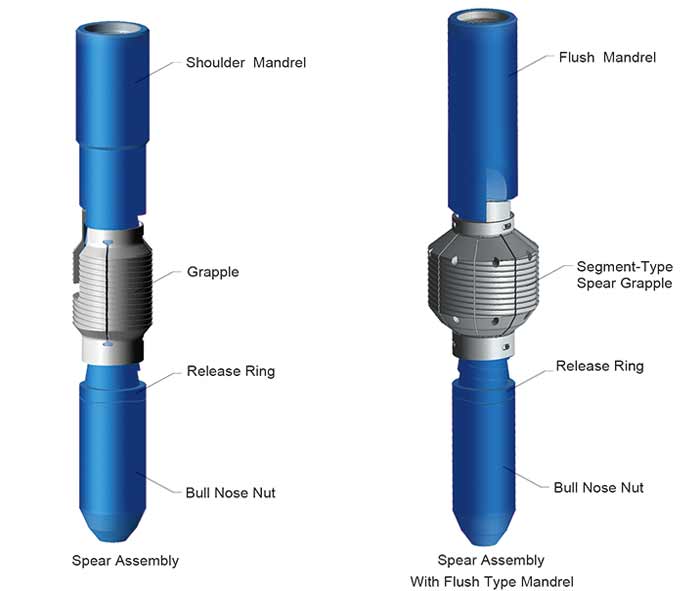

GAOTON Series 150 Releasing and Circulating Overshot is an external fishing tool for engage, pack off and retrieve tubular fish, especially for fishing drill collar and drill pipe. The grapple of the overshot can be designed for different sizes of fish, so one overshot can be dressed with different size of grapple components for fishing different sizes of fish.

GAOTON Series 150 Overshot consists of three outside parts: Top Sub, Bowl, and Standard Guide. The Basic Overshot may be dressed with either of two sets of internal parts, if the fish diameter is near the maximum catch of the Overshot, a Spiral Grapple, Spiral Grapple Control, and Type “A” Packer are used. If the fish diameter is considerably below maximum catch size (½” or more) a Basket Grapple and a Mill Control Packer are used.

Within those famous China oil and gas overshot manufacturers, GAOTON is a professional such supplier, producer and provider, welcome to wholesale petroleum and oilfield API overshot from our factory.

Xi"an ZZ Top Oil Tools Co.,Ltd as a manufacturer of downhole tools established in 2007 for supplying drill stem testing(DST) tools which is annular pressure operated and full bore type,the factory own advanced facilities and trained workers,all technical persons involve in the DST tools over 10 years,from year of 2009, we started to producing some well surface testing equipment i.e flowhead(surface testing tree), floor manifold, Surface safety valve as well as oil&gas manifold,transfer pump and so on.Our tools and equipment are widely used in domestic and aboard including USA,UAE,Iran,Colombia, Brazil,India,Pakistan,Jordan,Saudi Arab,Indonesia,Singapore and so on.Xi"an ZZ Top Oil Tools Co.,Ltd as a distributor of large factories in China supplying drilling equipment, well head&well control equipment, Fishing Tools, Completion tools as well as heavy forgings. All supplied products are produced as per API latest version.Xi"an ZZ Top Oil Tools Co.,Ltd is focused on building long lasting business relationships with members of the petroleum industry through leadership, innovation and partnership, insist on Traceability and Serialization, each tool, equipment and spare parts can be traceable by part number, be responsible for any failure caused by quality problem.Xi"an ZZ Top Oil Tools Co.,Ltd would like to cooperate with any clients based on honest and serious business, ZZ Top will exceed your expectations.

Russian exports of oil and natural gas are an essential source of hard currency that helps cover the cost of importing manufactured goods. Russia’s oil, gas, and coal exports arealsoan essential source of energy for European consumers and businesses, without which they couldn’t generate electricity, fuel their vehicles, or heat their homes and offices.

This entanglement limits the West’s ability to penalize Russian aggression financially. Yes, cutting Russia off from the global financial system would devastate the Russian economy and impose severe hardship on the Russian civilian population, but it would also force Europeans to slash their energy consumption.

Milder sanctions could protect Europe’s access to oil, coal, and gas, but their impact on the Russian government’s behavior would be commensurately smaller. The Putin regime has spent years acclimating Russians to material deprivation and it has also built up substantial financial buffers. Not for the first time, conservative macroeconomic and regulatory policies haveshielded a revisionist regime from international pressure.

There was nothing that Europeans could have done about the Russian government’s decision to impose severe costs on its civilian population for the sake of maintaining its own flexibility.But Europeans can and should be blamed for becomingeven morereliant on Russian fossil fuel exports since the 2014 invasion of Ukraine.They wasted nearly a decade when they could have been greening their economies and also increasing the security of their own neighborhood. Ukrainians—and others—will now have to live with the consequences.

The Russian government’sability to withstand financial pressure was hard-earned. Most obviously, total spending on imported goods and services (in U.S. dollar terms) has consistently been about 25-30% lower than it was before the first invasion of Ukraine. While some of this can be attributed to declines in the world prices of Russia’s oil and gas exports, Western sanctions and Russian domestic policies have also played a role.

The sustained drop in imports has left a mark on Russian consumers’ spending. In inflation-adjusted terms,Russian households spent 12% lessin 2016 than they did at the peak in 2014. Even in 2019—before the coronavirus pandemic upended the world economy—Russian consumers were about 2% worse off in material terms than they were before the first invasion of Ukraine.

Meanwhile, Russian businesses and other borrowers responded to external financial pressures—and domestic political ones—by slashing their foreign-currency denominated debt by $200 billion since the beginning of 2014. The Russian government also spent $200 billion adding to its stockpile of reserves (gold, bank deposits, and bonds) since mid-2015.

Shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine in early 2014, I wrote that Russiafaced a long-term strategic vulnerability: Europeans had the option to squeeze Russia permanently by reducing their reliance on Russian energy exports. At the time, about 60% of Russia’s total export revenues came from sales of crude oil, refined products, and natural gas—and much of that went to Europe.

The Europeans could have built out their capacity to import liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the U.S. and other allies. Even better, the Europeans could have reduced their reliance on fossil fuels altogether by building out more alternative energy generation.

Either way,Gazprom’s network of pipelineswould have been transformed from a source of leverage into an albatross. Russia could have found other customers for its gas—most obviously China—but building the necessary transportation infrastructure to compensate for the loss of the European market would take years. Russian oil could be sold elsewhere more easily, but the prices would have to be lower if European demand disappeared.

At first glance, it almost looks as if that’s what happened. Russia’s total export revenues from oil and gas fell from $350 billion/year before the first invasion of Ukraine to $231 billion in 2019. While Russians made up the difference by increasing other exports, including food, the squeeze on energy revenues is real.

In 2013, the countries ofthe European Union importedabout 135 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Russia. That was equivalent to about 70% of Russia’s total gas exports and equal to 37% of the EU’s worldwide gas imports. Yet in 2019, EU countries imported 166 billion cubic meters of Russian gas—23%morethan before the invasion of Ukraine. That was equivalent to 75% of Russia’s total gas exports and 38% of the EU’s worldwide gas imports in 2019.

European demand for Russian crude oil and refined petroleum products was slightly lower in 2019 than in 2013, but this was offset by surging European demand for Russian coal, which now accounts for almosthalfof the EU’s coal imports. Put another way, the countries of the EU went fromconsuming about 62 exajoules of energyin 2013 to 61 exajoules in 2019, while Russia went from supplying 10 exajoules of that energy in 2013 to 11 exajoules in 2019.Despite a slight decline in fossil fuel demand,Russia’s share of the European energy mix rose from 16.5% to 18.5%after the invasion of Ukraine.Europe’s dependence will only increase ifthe Nord Stream 2 gas pipelinecomes onstream as planned.

The perverse result is that Europe is at greater risk ofRussianpressure than the other way around. Natural gas prices in Europeare now about 5-6 times as high as in the U.S.because Gazprom has been withholding supply and because the lack of LNG terminals has prevented ships from moving gas across the Atlantic.

And while Europeans have made some modest investments in solar and wind energy over the past decade, it hasn’t been nearly enough to make a dent in the overall energy mix, especially after factoring in the impact of the decisions to decommission existing nuclear power plants.

The Europeans seem to have—belatedly—realized the implications of all this. As EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyenput it on Tuesday:This crisis shows that Europe is still too dependent on Russian gas. We have to diversify our supplies…We will have to massively invest in renewable energy…because this is a strategic investment in our energy independence.

Please send us your inquiry with detail item description or with Model number. If there is no packing demand we take it as our regular exported standard packing. We will offer you an order form for filling. We will recommend you the most suitable model according to information you offered.

We can give you really high quality products with competitive price. We have a better understanding in Chinese market, with us your money will be safe.

LONDON, Feb 18 (Reuters) - Brinkmanship has been one of the defining characteristics of the Trump administration, as the White House ramps up pressure to create a sense of crisis and force negotiating partners to make concessions.

The administration has employed the same tactics in trade negotiations with Canada, Mexico, South Korea and the European Union, as well as with the U.S. Congress for border security funding, with varied results.

In China’s case, however, the administration may have missed its moment of maximum leverage back in September-October 2018, and as a result may have to settle for a less ambitious deal.

Leverage is always relative and at the end of the third quarter China’s economy was showing signs of strain while the U.S. economy and markets were at the top of a growth cycle.

Since then, China’s economy has remained under pressure, but the U.S. economy and financial markets have also started to show signs of slackening momentum.

Global trade flows and manufacturing activity have shown even clearer indications that the rate of growth decelerated in the fourth quarter and early 2019.

Back in September-October, the administration could have risked imposing punitive tariffs on China and hoped to weather the economic fallout while waiting for China to capitulate.

But the economic and financial market situation is now much more fragile and punitive tariffs would threaten to tip the domestic and international economies into a recession.

News reports based on leaks from inside the talks process suggest the two sides have been inching towards an interim understanding, despite remaining far apart on some of the most contentious issues.

The talks may have to settle for a partial agreement, in which the two sides reach agreements on farm and energy trade, goods and services, but leave tougher issues on intellectual property, technology transfers, subsidies and state-owned enterprises to be settled later.

Hardliners in the United States have been upping the pressure on the administration not to settle for anything less than a comprehensive deal that transforms China’s economy and ensures fair trade.

For maximalists, the risk of short-term cyclical damage in the form of a recession is worth taking to ensure longer-term structural gains and entrench U.S. technology and economic leadership.

For the White House, however, structural objectives must be balanced against recession risk and an inexorable political cycle that has presidential and congressional elections less than 21 months away (and primaries less than 12 months away).

The administration is likely to put the economy at the centre of its re-election campaign in 2020 and a cyclical downturn would complicate that narrative.

A broad range of U.S. economic and financial indicators show the rate of expansion peaking at the end of the third quarter or early in the fourth, before slowing significantly:

* The U.S. S&P 500 equity index hit a cyclical high in late September and slid 20 percent by late December, before recovering partially to be around 5 percent down (mostly on hopes tariffs will be avoided).

* Benchmark yields on 10-year U.S. Treasury notes hit a cyclical high between late September and early November, before slumping amid concerns about a deteriorating economic outlook.

* Business surveys show U.S. manufacturing activity growing rapidly through October-November, decelerating in December and January, according to the Institute for Supply Management.

* First-time claims for unemployment insurance reached a cycle low in September and have since trended gently higher, according to the U.S. Department of Labor’s Employment and Training Administration.

* Consumer sentiment hit a cyclical high in September-November before softening through the end of the year and into 2019, according to the University of Michigan’s Survey Research Center.

The slowdown has been even more marked outside the United States, with global manufacturers reporting export orders falling since September, and the decline is accelerating.

Container trade volumes through major cargo hubs including Singapore, Los Angeles and Long Beach all show a sharp slowdown in the second half of 2018 and into 2019.

The rebound in U.S. equity markets and steadying of consumer and business sentiment over the last month have been largely attributed to hopes that the trade negotiators will reach a deal or at least postpone tariff increases.

Top policymakers, including the U.S. president, have fuelled financial market optimism by describing positive progress made in the talks, and the hopeful sentiment has spilled over into commodities such as oil.

Markets are banking on a deal (even a limited, incomplete one, or a talks extension) to keep the U.S. and global economies growing and avoid a slide into recession.

China would undoubtedly take a severe economic hit if the talks fail and punitive tariffs go into effect, but the United States might be hit even harder in relative if not absolute terms.

China’s currency hit a low against the U.S. dollar at the end of October and has since appreciated significantly, in a measure of shifting relative economic performance.

The administration has a mixed track record on brinkmanship, securing some gains, but also miscalculating the determination and resilience of its opponents in some cases.

But both the United States and China, and specifically their top leaders, have a lot to lose if the talks fail, which is the main reason they are likely to succeed, even if the price is deferring some of the harder issues until later.

Oil prices have rallied to multiyear highs on surging demand, tight supply, and the crunch on natural gas. Brent crude futures, the benchmark in global energy markets, hit a three-year high of above $86 a barrel in late October. Futures for West Texas Intermediate (WTI), the U.S. benchmark, surpassed $85 a barrel, the highest since October 2014. We analyze the dynamics of the crude market below.

The key question is whether the rally in oil prices can be sustained. Rising natural gas prices and a cold winter could lead to a further increase in prices. However, this rally has extended beyond market fundamentals. Oil markets are historically volatile, and should crude overshoot current levels, a correction would likely be sharp. From a trading perspective, this isn’t the right time or price to take long positions, in our view. That is partly because many sell-side commodity traders are revising their forecast to $100 a barrel, while physical markets aren’t showing a level of tightness consistent with that.

It’s true that in the United States, inventories of crude and petroleum products have fallen below the five-year average. This indicator, however, is misleading due to the jump in inventories during the Covid-19 pandemic. It is fair to say that inventory levels are now close to those of late 2018 and early 2019. During that period, oil prices were volatile, between $40–$70 a barrel.

Our fair value model for oil shows $69 a barrel for WTI. But prices have already overshot this level, showing the steepest increase since we started our fair value analysis. In our view, for oil to continue to trade at more than $80 a barrel, inventories will need to decline in January and February — the seasonally weakest months of the year. If inventories do not decline during this winter, we believe prices of WTI in the futures market will likely converge to our fair value to reflect existing supply-demand conditions.

Why are prices overshooting? We believe it is because of concerns about shortages as the northern hemisphere heads into winter. It has little to do with oil’s physical markets. Prices of other energy sources, natural gas, and coal, have spiked due to low inventories, rising demand from China, and worries about a cold winter. The surge in global natural gas and coal prices has also lifted oil futures, partly because of expectations about rising demand for cheaper oil. There are also supply shortages for light, sweet crude in Europe.

Demand for light, sweet crude is high because of refinery dynamics, including its lower refining cost. Refineries are heavy users of energy. Complex and profitable refineries process high sulfur oil (cheaper oil) at hydrocrackers that use hydrogen generated from natural gas. Higher gas prices in Europe and Asia have raised the operational cost of these hydrocrackers. As a result, crude inventories remain low in Cushing, Oklahoma, a storage hub and delivery point for the NYMEX WTI futures contract, while more barrels are being diverted to fill the new Capline pipeline in Illinois. These dynamics have contributed to the low price spread between Brent and WTI crude.

Demand, however, remains low for heavier, sour crude. There are still unsold barrels of this oil in the Middle East, including the Upper Zakum grade crude from the United Arab Emirates. West African grades are also having a tough time as freight costs increase. In addition, China’s limited oil import quotas are having a troubling impact on oil from Angola.

The rally in the futures market has extended beyond the fundamentals of the physical markets, in our view. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and its partners (OPEC+), a 23-nation grouping led by Saudi Arabia and Russia, are sellers in the real market. They are more concerned about the physical market for oil versus the financial markets.

A colder winter could send natural gas and coal prices soaring, and this could impact crude prices as companies and manufacturers further switch to using oil. However, because we rely on physical markets, and not necessarily the weather, to forecast the trend in oil markets, we believe it is time to question the current rally. We have a neutral view on oil prices over the short term and a bearish view over the long term.

This material is provided for limited purposes. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument, or any Putnam product or strategy. References to specific asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or investment advice. The opinions expressed in this article represent the current, good-faith views of the author(s) at the time of publication. The views are provided for informational purposes only and are subject to change. This material does not take into account any investor’s particular investment objectives, strategies, tax status, or investment horizon. Investors should consult a financial advisor for advice suited to their individual financial needs. Putnam Investments cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any statements or data contained in the article. Predictions, opinions, and other information contained in this article are subject to change. Any forward-looking statements speak only as of the date they are made, and Putnam assumes no duty to update them. Forward-looking statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks, and uncertainties. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. As with any investment, there is a potential for profit as well as the possibility of loss.

Consider these risks before investing: International investing involves certain risks, such as currency fluctuations, economic instability, and political developments. Investments in small and/or midsize companies increase the risk of greater price fluctuations. Bond investments are subject to interest-rate risk, which means the prices of the fund’s bond investments are likely to fall if interest rates rise. Bond investments also are subject to credit risk, which is the risk that the issuer of the bond may default on payment of interest or principal. Interest-rate risk is generally greater for longer-term bonds, and credit risk is generally greater for below-investment-grade bonds, which may be considered speculative. Unlike bonds, funds that invest in bonds have ongoing fees and expenses. Lower-rated bonds may offer higher yields in return for more risk. Funds that invest in government securities are not guaranteed. Mortgage-backed securities are subject to prepayment risk. Commodities involve the risks of changes in market, political, regulatory, and natural conditions. You can lose money by investing in a mutual fund.

Fishing tool is a special fishing drilling tool used to retrieve fallen objects from the borehole. At any stage of the operation, the drill rig operator will encounter unexpected situations, such as falling drill string, stuck pipe, missing drill bit, etc. The equipment that falls into the well is called "fish" or "trash", and the tools used to remove the equipment are called "fishing tools." Sometimes it may be necessary to use "fishing tools" to retrieve older wellbore equipment, such as packers, liners, tubing, or any stuck objects in the well. The drilling tools for fishing must be retrieved from the borehole in order to continue drilling operations.

Overshot is a very common fishing tool. The main fishing object is a smooth tube fish, which belongs to the external fishing type (i.e. catching the external surface of the fish).

Taper tap and die collar are common fishing tools for fishing the inner hole of the string. They are used for fishing the inner hole with holes such as tubing, drill pipe, casing milling pipe, packer, water distributor, etc. It is made of high-quality alloy steel and especially heats treated. It has the advantages of high strength, high toughness, and simple buckle making.

More green fuels are coming, but so is a larger global fleet causing shipping to overshoot its carbon budget. Can it be stopped? Discover looks at the incentives and regulations needed to reach net-zero emissions by 2050.

At first glance, the outlook Anders Kryger paints for the maritime industry’s goal to reduce emissions isn’t all that optimistic: “Maybe we’ll reach net-zero CO2 emissions by 2050, but there’ll be a massive overshoot of emissions

“We’re long past the deadline,” says Kryger, who compares the goals to a bank account: “We know what the balance should be. But we’re drawing deficits each year. If CO2 develops as we expect, the balance will be -25,000 gigatons in 2050 compared to 2008, even if we hit net zero. And that’s a real driver of global warming!”

Kryger’s study shows that while we wait for international regulation to be passed there will be a twofold development. On one hand, driven by consumer demand and expected changes in regulation, the share of e-Fuels like ammonia, methanol and methane in shipping will grow steadily from the year 2030, which will reduce CO2 emissions. This is directly connected to the availability of technology: Engine producers like MAN Energy Solutions already offer engines based on methanol. And the first ammonia-fired engines will be available in 2024, which will make ammonia and methanol the most-used fuels by 2050.

But on the other hand, driven by international trade and economic growth, the fleet will grow by 60 percent over the next three decades, up from today’s 3 billion deadweight tonnes to over 5 billion in 2050. And although the well-to-wake emissions will start to drop by the end of this decade if regulation comes into force, the overall growth of the fleet will further add to the massive overshoot that Kryger is depicting. “The consequence will be that we won’t reach the main goal of the Paris Agreement: to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees,” says Kryger.

So what can be done? “Today, companies are doing all kinds of things that point to the right direction,” says Kryger, “but we need a more targeted approach, a common direction. And that’s only possible through regulation.”

Newbuilding is on the right path, but needs further incentives to make a larger share of contracting dual-fuel engines, which build the basis for maritime shipping with synthetic fuels in the future. This year around 50 percent of MAN Energy Solutions’ new orders in the two-stroke business have been for dual-fuel engines – already a clear sign in the right direction. Decarbonizing the existing fleet, however, is a paramount challenge and requires special attention from lawmakers. MAN estimates that 2,300 vessels sailing the ocean today are appropriate candidates for a conversion to dual-fuel propulsion, resulting in saving as much as 86 million tons of CO2 emissions per year when fueled by carbon-neutral fuels.

There’s rising pressure from public opinion for shipping to contribute their share in the common effort against climate warming: Today, the sector contributes around 2.5 percent to global emissions. And as the consequences of climate warming are getting more and more visible for people all over the world through extreme weather events, the industry can only expect the public pressure to continue to grow.

There are also more and more companies asking ship-owners about their emissions too – because they want to reduce the overall CO2 footprint of their products, including transportation. “That’s why we’re seeing a significant rise of inquiries from the shipping industry for engines with alternative fuels,” says Wayne Jones, Chief Sales Officer and member of the Executive Board of MAN Energy Solutions.

“The technology is there. But the crucial question is how we build up big enough production facilities for climate-neutral fuels,” says Peter Müller-Baum, Managing Director Engines and Systems at the Mechanical Engineering Industry

Association (VDMA), Europe’s largest networking platform for the mechanical and plant engineering industry in Europe . “That means billions in investments. And companies will only invest if they understand there’s a market.”

Recently, VDMA and the German Shipbuilding and Ocean Industries Association (VSM) released a Power-to-X roadmap, detailing how shipping in Europe could stop emitting CO2 as early as 2045 – much quicker than currently being discussed by regulatory

Power-to-X produces green fuels through electrolysis using renewables and is pivotal to decarbonizing shipping. But because it will take time to scale up production to reach the immense volumes required for the shipping industry, the industry will also

Captain Richard von Berlepsch, Managing Director of Hapag-Lloyd"s Fleet, which is planning to reduce its emissions by 60 percent until 2030 and already retrofitting some of its vessels to alternative fuels, agrees with Müller-Baum.

In 2019, Hapag-Lloyd was the world’s first shipping company to convert a large container vessel to run on liquefied natural gas (LNG) – the 15,000 TEU vessel “Brussels Express”. And while the company’s focus is on

biomethane and synthetic methane with dual-fuel engines, they can imagine e-Methanol or e-Ammonia being used in the future. “Technically, the solutions are there,” says von Berlepsch. “The shipping industry is ready to move, but

“Today we’re still living in the age of burning cheap oil in our ships’ engines – and of course, e-Fuels are going to be more expensive,” says Müller-Baum.

Richard von Berlepsch adds: “The challenge is: Everybody wants green transport, but nobody wants to pay for it. Customers have to understand decarbonization won’t come at zero cost. They’ll have to pay their share as well.”

In 2019, Hapag-Lloyd was the world’s first shipping company to convert a large container vessel to run on liquefied natural gas (LNG) – the 15,000 TEU vessel “Brussels Express”.

For Kryger, one step in the right direction could be to create “green corridors” from and to regions that are investing into the production of e-Methanol. For example, this could be the trade route between Amsterdam and Singapore or a transpacific corridor between Los Angeles and Shanghai. However, establishing green corridors like these requires public-private collaborations..

VDMA’s Müller-Baum is convinced that regional regulations could be a driver. “The EU could set strict regulations for its inner shipping industry. That will put the EU into the prime mover role and show the rest of the world that it works.”

This paper shows that the shipping sector will have a massive carbon overshoot where annual actual emissions and expected future emissions greatly exceed what is required to limit the global temperature increase to 1.5°C by midcentury.

Berlin-based journalist Moritz Gathmann’s work has appeared in a number of media outlets, including Der Spiegel, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung and Zeit online.

Synthetic natural gas (SNG) and methanol can bring renewable energy to sectors where direct electrification isn’t possible or practical. Here’s how they’re made.

Legal status (The legal status is an assumption and is not a legal conclusion. Google has not performed a legal analysis and makes no representation as to the accuracy of the status listed.)

Priority date (The priority date is an assumption and is not a legal conclusion. Google has not performed a legal analysis and makes no representation as to the accuracy of the date listed.)

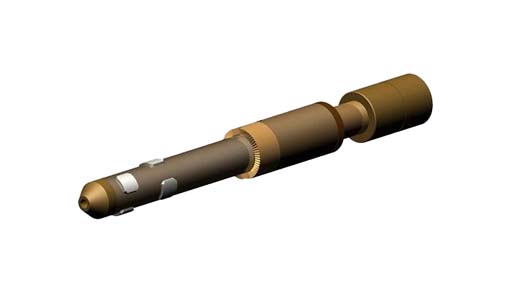

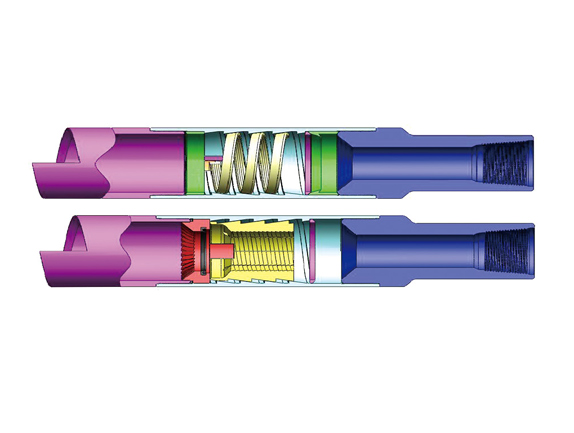

The utility model relates to an overshot, in particular to an overshot for the downhole operation of an oilfield, mainly comprising an upper joint, a cylinder, a slip, a guiding shoe and a slip frame. The upper joint is movably connected with the upper part of the cylinder, the lower end of the cylinder is connected with the guiding shoe, the slip is cylindrically arranged at the upper end of the guiding shoe in the cylinder, the upper end of the slip frame is connected with the upper joint, the lower end of the slip frame is connected with the slip, and a guiding pin is arranged at the joint of the upper joint and the slip frame. The vershot has the advantages of wide fishing range excellent performance, simple structure and reliable article salvage, can realize fishing and quit if necessary, and therefore the vershot is a novel fishing tool.

Oil-water well is produced or examines in the pump maintenance process, broken small workpiece such as plug, pincers tooth, valve ball, well head nut often occur and fall into the interior situation of sleeve pipe, so just require trouble of lost tool in hole is salvaged, in fishing, because trouble of lost tool in hole is not understood, so just require the salvaging scope of fishing tool big, existing smallclothes fishing junk instrument can not be brought into play better action in work progress, often one is not all rightly changed one again, cause the construction period long, operating cost is high.

The purpose of this utility model is exactly the above-mentioned defective that exists at prior art, and a kind of oilfield downhole operation fishing socket is provided, and the salvaging scope is big, and function admirable is simple in structure, high efficiency.

Its technical scheme is: mainly be made up of top connection, cylindrical shell, slips, guide shoe, slips frame, top connection flexibly connects the top of cylindrical shell, the lower end of cylindrical shell connects guide shoe, and slips becomes tubular to be positioned at cylindrical shell guide shoe upper end, and slips frame upper end connects the top connection lower end and connects slips.

The beneficial effects of the utility model are: the salvaging scope is big, can realize grabbing dragging for and withdrawing from fish in case of necessity, and its function admirable, simple in structure can make the engineering time shorten, and reduces operating cost, enhances productivity.

The utility model mainly is made up of top connection 1, cylindrical shell 2, slips 3, guide shoe 4, slips frame 5, top connection 1 connects the top of cylindrical shell 2, the lower end of cylindrical shell 2 connects guide shoe 4,3 one-tenth tubulars of slips are positioned at cylindrical shell 2 guide shoes 4 upper ends, slips frame 5 upper ends connect top connection 1, the lower end connects slips 3, and described top connection 1 is provided with guide finger 6 with slips frame 5 junctions.

During construction operation, be connected with fishing socket top connection 1 with oil pipe, slowly transfer it is entered in the fish, by on carry or transfer, cause in the track groove of the fairlead of guide finger 6 in top connection 1 and move, realization guide finger 6 does not rotate can salvage or discharge fish; Certainly, also be used in rigid down-hole smallclothes junks such as salvaging the little plug of load, steel ball, pincers tooth, well head nut in the big annular space.

1. oilfield downhole operation fishing socket, it is characterized in that: mainly form by top connection (1), cylindrical shell (2), slips (3), guide shoe (4), slips frame (5), top connection (1) connects the top of cylindrical shell (2), the lower end of cylindrical shell (2) connects guide shoe (4), slips (3) becomes tubular to be positioned at the upper end of cylindrical shell (2) guide shoe (4), slips frame (5) upper end connects top connection (1), and the lower end connects slips (3).

2. oilfield downhole operation fishing socket according to claim 1 is characterized in that: described top connection (1) is provided with guide finger (6) with slips frame (5) junction.

This week, at the annual “two sessions” political gathering in Beijing, the Chinese government approved a key policy document that will heavily influence the nation’s economic development – and climate policies – over the next decade and beyond.

Following a week-long meeting, the National People’s Congress (NPC) of China yesterday formalised the “outline for the 14th five year plan and long-term targets for 2035”.

In short, the five year plan’s outline sets a 18% reduction target for “CO2 intensity” and 13.5% reduction target for “energy intensity” from 2021 to 2025. For the first time, it also refers to China’s longer-term climate goals within a five year plan and introduces the idea of a “CO2 emissions cap”, though it does not go so far as to set one.

These new targets have triggered widespread discussion about China’s ambition to tackle its rising emissions. Some have expressed scepticism which questions the five year plan’s “shortfall” relative to its longer-term climate pledges. Others say China has a history of overachieving its targets and this needs to be taken into account.

Gathering together the reaction of various China experts, the Q&A also explains how the outline agreed this week is just a foretaste of the range of regional and sectoral plans due to be published over the next year.

“Two sessions” is a collective term for two major national political meetings held in China every spring. Known as “liang hui” in Mandarin, they are the plenary sessions of the National People’s Congress (NPC), China’s top legislative body, and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), the country’s top political advisory body. It is worth noting that the CPPCC does not hold any legislative power.

With thousands of attendees each year, the two sessions normally open on 3-5 March in Beijing – with the CPPCC taking the lead – and run for 10-12 days. There have only ever been two exceptions to their opening dates, both due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Last year, the sessions were postponed to May, while this year their duration was shortened to six-and-a-half days.

During the annual conferences, the leadership of China’s ruling party – the Communist Party of China (CPC) – sets out its vision for the next 12 months. The central government reviews and approves national economic and social development plans and receives reports of the implementation of previous plans. Thus, the two sessions are considered the most important annual political gatherings in China.

This year’s two sessions carry extra significance because they also oversaw the approval of the nation’s next “five year plan” – the 14th in a series stretching back to 1953. They were also held just months after Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced China’s new ambition to enhance its climate pledge for 2030 – its nationally determined contribution under the Paris Agreement – and to reach “carbon neutrality” by 2060.

This year, Chinese leaders gathered at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing to cast their gaze on the nation’s post-coronavirus economic growth. They have also set key energy and climate targets that will guide the country over the next five years, in addition to setting long-term “prospects” for 2035. This provides policymakers with a “direction of travel” for what they have to deliver over the next 15 years.

Owing to Xi’s pledge last September, “CO2 emission peak” and “carbon neutrality” were two of the most popular topics among the sessions’ participants this year. For example, influential participants from energy companies, heavy-industry manufacturers and technology firms introduced a series of proposals at the two sessions on ways to reduce the nation’s emissions.

A five year plan, or FYP, is a comprehensive policy blueprint released by China every five years to guide its overall economic and social development.

The system was first used by the Soviet Union in 1928 under Stalin’s rule and later adopted by the Communist Party of China to set out economic quotas for a newly founded People’s Republic of China.

Since then, China has released and implemented 13 of these guidelines, which are made up of a series of documents at national, sectoral, provincial and regional levels.

At this week’s two sessions, the NPC reviewed and approved the “outline for the 14th five year plan for economic and social development and long-range objectives through the year 2035” (shortened as “outline”), which had been in the making since 2018.

The outline’s preparation and formulation involved several key government organs, including the State Council, China’s highest administrative authority led by the premier, and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CCCPC), a political body comprising top leaders. (A recent Carbon Brief article gave more explanation about China’s governance structure.)

The drafting of the 14th outline began in late 2020 after the CCCPC had conducted relevant research and deliberation, before presenting its assessment of the country’s situation in a formal “opinions” document to the State Council. The council then drafted the outline, after receiving this opinion document.

Timeline showing the key steps in the formulation, implementation and evaluation of the 14FYP. Source: Information based on details revealed in news from a stated-affiliated media. Chart by Tom Prater for Carbon Brief.

The outline is commonly referred to in media reports outside of China as if it is “the 14th five year plan”. Importantly, however, the outline serves as an overarching guideline for the successive forumulation of more detailed planning for 2021-2025, which includes sector-specific planning such as on the cement industry, and thematic planning such as on national security, as well as administrative planning at all levels, from central, provincial, municipal down to county level.

These plans are due to be published later in 2021 and in early 2022, to break down the targets set in the outline at sectoral and administrative level, and to provide detailed action plans for implementation, evaluation and reporting.

For the 14FYP, they will include plans on peaking CO2 emissions by 2030 and on energy saving and emission reduction formulated by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), on energy, renewable energy, coal, electricity development forumuted by the National Development and Reform Council (NDRC) and the National Energy Administration (NEA), and on energy intensive industrial sectors such as iron and steel, cement, aluminium and chemicals formulated by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT).

Energy and climate indicators are included under “new progress of ecological civilisation”, which is one of the six overarching economic and social development goals of the 14th five year plan. This section appears in the text after the goals on economic reform and society and before those on public welfare and governance.

Furthermore, “energy” appears in a dozen other chapters, such as ecological planning, green economy, environmental protection and resource conservation, national economic security and energy and resource safety strategy.

In comparison, the word “energy” is mentioned six times more frequently than “climate” in the text. The terms “climate” and “climate change” appear just nine times, mainly in the section titled “actively responding to climate change” (see below).

In total, the 14FYP’s outline devotes four of its 20 “indicators” on economic and social development to energy and climate change (see table below), including half of the “binding” targets. This means that the central government is determined to achieve them as part of its political key performance indicators (KPIs).

Specifically, as shown in the table above, the outline requires an 13.5% reduction in the nation’s energy consumption per unit of GDP – also known as “energy intensity” – during the 2021-25 period and a 18% cut in its CO2 emissions per unit of GDP, also known as “CO2 emissions intensity”. (just below the table of indicators).

The outline calls for an improvement of the forest coverage rate from 23.4% in 2020 to 24.1%. Moreover, it expects the country’s total energy production to reach more than 4.6bn tonnes of coal equivalent from coal, petroleum, natural gas and non-fossil energy. Previous five year plans had set a cap on energy production rather than a minimum level.

The first three of these binding energy and climate goals are considered “green ecology” targets, while the fourth, on energy production, is categorised as security-related.

As for climate change, the 14FYP outline reaffirms the implementation of the NDC for 2030 without listing specific new targets. It also demands that the nation formulates an action plan on how to peak CO2 emission before 2030, as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, the 14FYP outline presents a list of “construction projects for the modern energy system”. It covers six key areas of energy development, including the construction of eight large-scale clean energy “bases”, coastal nuclear power, electricity transmission routes, power system flexibility, oil-and-gas transportation and storage capacity. The geographical distribution of the key projects is illustrated in the map, below.

The 14FYP outline proposes the construction of eight major clean energy bases across China (orange areas outlined by dotted lines). It also maps out a programme to transfer clean energy from these bases to eastern China – where the nation"s most prosperous provinces and industrial bases are situated – through so-called power transmission routes (“tunnels”). The blue arrows represent the projects to be constructed and put into use during the 14FYP period. The red arrows represent those planned by the 13FYP due to go into operation during the 14FYP period. The grey lines stand for the main power transmission lines that have already been constructed. Major power generation centres are illustrated by fuel, as follows: hydropower (blue water turbine), offshore wind (blue wind turbine), fossil-fuelled thermal power (red), nuclear (brown), onshore wind (green wind turbine) and solar power (black). Source: Screenshot from the draft for adaptation of the 14th FYP published by the NPC (2021).

Experts interviewed by Carbon Brief say that more detailed targets on climate actions, such as the total CO2 emission control target (the “CO2 emission cap”), are most likely to be disclosed in the 14FYP on greenhouse gas emission control and prevention.

Similar to 12FYPs and 13FYPs, experts expect more detailed targets for the energy sectors, such as the coal consumption and production, renewable energy development and utilisation, and electrification rate and electricity power structure, to be announced in sector specific plans issued by NDRC and NEA in the coming year.

According to the technical guidelines, this will include a series of detailed indicators – shown in screenshot below – such as total energy consumption, energy mix, share of fossil fuel in total energy consumption, and dual CO2 emission caps – intensity and absolute emissions – on industry, building, transport, agriculture and homes.

The 14FYP outline has left many unanswered questions concerning China’s energy transition and its efforts to tackle climate change. For example, the outline stresses that the nation should implement a cap system that is “based primarily on carbon intensity control, with the absolute carbon cap as a supplement”. Yet, the outline does not give an exact number on the CO2 emission cap.

In response to some international observers’ comments on the outline being “conservative”, or lacking strict measures, Chinese experts interviewed by Carbon Brief say they expect such details to be clarified in the 14FYP’s forthcoming sector-specific and regional plans. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) will set targets for nationwide greenhouse gas emission controls between late 2021 and early 2022.

Such analysis shows the energy and CO2 intensity targets could still be met, even as overall emissions increase, depending on the rate of GDP growth over the plan period. Notably, however, the 14FYP outline drops a five year GDP growth target in favour of year-by-year goals, meaning such emissions calculations are uncertain.

The table below is taken from analysis published by Lauri Myllyvirta at the Centre for Research and Clean Air, which shows what could happen to a variety of targets, according to three different levels of GDP growth.

Indicative calculations of China’s energy consumption and CO2 emissions trends until 2025 under the five-year plan targets, depending on the GDP growth rate. Source: Screenshot from analysis published by Centre for Research and Clean Air (CREA).

Similarly, some observers and media have expressed disappointment about the lack of clear language regarding the phasing out of coal. For example, the share of coal in the energy mix is missing, as is the total coal consumption control target (“coal cap”). The latter, first introduced in the 13FYP on energy development published in 2016, was a “binding indicator”, which required the percentage of coal consumption in total energy consumption to drop from 64% to 58% over five years.

Min Hu, executive director of the Innovative Green Development Program (iGDP), points out that an “energy consumption cap” already existed in previous energy planning for the 2030 energy revolution, which sets a total control target for total energy consumption at “no more than 6bn tonnes of standard coal” by 2030.

Dr Fuqiang Yang, a distinguished researcher of the Institute of Clean Energy at Peking University, underlines the “superior” political priority for the Chinese government of achieving an emissions peak and, ultimately, carbon neutrality. He believes that, as a result, a “coal cap” for 2021-2025 will eventually be announced in the subsequent FYP on energy development and coal development, which the National Development and Reform Council (NDRC) and National Energy Administration (NEA) are now formulating.

He adds that the outline’s binding indicators on energy will still have an actual effect on restricting coal consumption and its share in the energy mix – even without an explicit “coal cap”. He explains to Carbon Brief:

“Based on current targets, by 2025, non-fossil energy will definitely reach 20%. Natural gas steadily increases by 3% every five years, so we can assume that it will reach 11.5% in 2025 and oil may account for 18.5%. Under the [non-fossil energy] target, the share of coal in the energy mix must [therefore] be reduced to at least 50% or below – and I think it’d be very likely to drop to 48%, in comparison to 56.8% in 2020.”

Despite the absence of the “coal cap” and CO2 emission cap, Min Hu still thinks the outline sends out a “very important signal”. She tells Carbon Brief:

Professor Ji Zou, chief executive and president of the NGO Energy Foundation China (EFC), agrees that these targets do not “come easy”. He says, until early 2020, there was still much debate among policymakers and their advisors on whether incorporating low-carbon development targets would bring a “big shock to the economy”. The economic slowdown after the Covid-19 lockdowns made the decision even more difficult. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The debate was very fierce: one side pushed for incorporating more low-carbon indicators and more ambitious and stringent targets, while the other side insisted on reducing binding targets for deepening the reform towards a market economy. The hesitation continued until the end of last summer and momentum was finally achieved under the strong political determination on furthering decarbonisation. In the autumn, the top leadership set the tone for the 14FYP: the plan is to not only continue the path on low-carbon development, but also to accelerate the transition, in particular, to incorporate the carbon-neutrality target into the planning.”

In addition, the 14FYP outline specifies that China should “strive to increase the storage and production of oil and gas” and “accelerate the construction of natural gas network pipelines”. This is consistent with China’s national policy on coal-to-gasin the 13FYP under the dual pressure of air pollution “control and prevention”, as well as energy and CO2 intensity reduction.

Most recently, the “No1 central document”, which was co-issued by the CCCPC and State Council in 2021, also lists “promoting natural gas to enter rural areas” as part of the clean energy infrastructure project.

Dr Jiang Lin, a China energy expert at the University of California-Berkeley, tells Carbon Brief that natural gas has been at the centre of the debate on energy transition. The discussion is partially caused by natural gas’s role as a form of “transitional energy” to replace coal. It is also spawned by the potential danger of a high-carbon lock-in due to the fact that natural gas is a fossil fuel. He adds:

“Natural gas has a positive contribution to reducing air pollution and to meet the peak demand for power in certain situations. However, if we want to arrive at a net-zero future, we have to also bring down the emission from natural gas to zero. [Continuing to develop natural gas] is not 100% aligned with the carbon neutrality goal in the long-term.”

Leading Chinese energy and climate experts interviewed by Carbon Brief say China is “on track” to fulfil its promise of peaking emissions by 2030, although many say more efforts would be needed for China to meet the carbon neutrality target by 2060.

A study from December 2020 reviewed the available scenarios under which China could reach net-zero emissions by 2060. It concluded that an 18-20% reduction of CO2 intensity during the 14FYP period would put the country on the trajectory towards carbon neutrality by 2060 and would be consistent with a 1.5C temperature rise globally, as shown in the chart below.

The research was published by EFC and written by a group of Chinese and international climate scientists, including advisors to the State Council and National Development and Reform Council (NDRC), as well as three Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) co-chairs and lead authors.

Prof Zou says appeals from “international colleagues” for more stringent climate targets and ambitious policies are sensible, but they also reflect a general misunderstanding about China’s political process and its overall strategic objectives for the next four decades. He tells Carbon Brief:

“It’s too early to say whether the 14FYP is ambitious enough for carbon neutrality in 2060. We are standing at the beginning of a five year plan. We can’t simply conclude whether China could achieve the goal in 40 years based on its performance in five years, which is only one-eighth of the length up to 2060. We have to look at the trajectory forward.”

Dr Lin, who has carried out several modelling research projects into China’s decarbonisation scenarios, says based on the research findings, it is “highly possible” for China to peak its emissions by 2030. He also thinks the country’s decarbonisation transition would stimulate economic growth and bring a series of additional benefits, such as creating more jobs.

To date, a total of three targets have been announced, namely, the 12FYP (2011-2015), 13FYP (2016-2020) and 14FYP (2021-2025), as shown in dark blue. In reality, China overperformed on this target twice in row, as shown in red.

CO2 intensity targets (blue) in the 12FYP (2011-2015), 13FYP (2016-2020) and 14FYP (2021-2025) versus actual performance (red). For the 14FYP, a projection of expected performance is shown in pink. Source: State Council (2011, 2016, 2021) and Tsinghua ICCSD (2020). Produced by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

For the current 14FYP period, China is expected to once again overachieve with an estimated 19.4% reduction in CO2 intensity, according to research by 18 leading climate science institutes in China, led by Tsinghua University’s Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development (ICCSD). This reduction would put China on a path to overachieving the CO2 intensity target in its NDC for 2030, the research suggests.

“Looking back, most of the targets – from renewable energy installed capacity through to CO2 intensity – were overperformed. We cannot calculate the trajectory simply based on the targets illustrated in the 14FYP outline and say that they will not be sufficient for [the 2060 climate neutrality pledge].”

Dr Yang, who has spent the past four decades working on energy and climate policies in China, has a different view. He says he fully understands the “conservative considerations” from the top policymakers, who usually do not make promises they cannot fulfill – a logic that is deeply rooted in China’s political culture. Nevertheless, Dr Yang calls for more ambitious targets and “daring” thinking from the nation’s leaders, due to the urgency of climate change. He tells Carbon Brief:

According to Prof Zou, expected improvements in CO2 intensity mean that most provinces in China could reach peak emissions, or come close to it, during the 14FYP period, based on a yet-to-be-published study compiled by the Energy Foundation China. With provinces and cities that contribute around 80% of China’s emission “having peaked” or “expected to peak before 2025”, he believes achieving nationwide peak emissions during the 14FYP is a “low-hanging fruit”.

In the past, the central government has used mandatory top-down instructions to resolve issues surrounding energy consumption and energy intensity. But there have been substantial disadvantages and setbacks, such as cutting of power supplies to meet targets.

During the 13FYP, China introduced a “dual-control” policy, demanding that energy consumption per unit of GDP – energy intensity – be reduced by 15% by 2020 compared with 2015. The policy also required that total energy consumption remained under 5bn tonnes of standard coal equivalent (tce). The State Council then divided the national “dual-control” goals into goals for individual provinces.

However, Dr Yang says: “With only a few employees in the National Energy Administration, how can the goals be reasonably broken down [and implemented]?”

He adds that many provinces were unsatisfied, saying the goals were unrealistic, which caused serious consequences. For example, Zhejiang province, which is just south of Shanghai, resorted to limiting electricity consumption and even cutting off electricity at the end of 2020 to achieve its goal. This forced many factories to halt production and left a large number of residents without heating in winter.

Dr Yang says that the plan to use “the carbon cap as a supplement” demonstrates that a cap will eventually be set up during the 14FYP period. But he believes that the formulation of the cap will not be top-down, but rather bottom-up, which means that the central government will not set an overall cap and then send individual targets to the provinces.

Instead, each province and sector would determine its own targets and those would then be aggregated into a national carbon cap. He says this is a “more reliable plan”.

Ma Jun, the director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), an environmental research NGO based in Beijing, agrees with Dr Yang. Ma says that there are also some “technical reasons” for China not to mention a carbon cap in the 14FYP. For example, there is little research to date into how China can best achieve its new carbon neutrality goal.

“Recently, a local official told me that carbon peaks are not difficult to achieve. If we built a batch of high-carbon projects during the 14FYP and 15FYP periods and then stopped afterwards, won’t we easily achieve a carbon peak that way?”

Dr Jinnan Wang, a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and dean of the Environmental Planning Institute of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, makes a similar point. He said in an interview with China Energy News, a state-affiliated media, in January:

“Many provinces believe that the use of fossil energy can continue to be substantially increased before 2030. They are even planning to first reach a new and higher peak of carbon emissions during the 14FYP and will only consider the decline after reaching the ‘new peak’.”

Dr Yang says this is similar to how international climate agreements have worked. The Kyoto Protocol was a top-down, compulsory allocation of targets to countries and some have argued that it was not successful. Now, under the Paris Agreement, it has changed to a bottom-up approach, with countries putting forward their own NDCs every five years under the so-called “ratchet mechanism”.

The bottom-up approach is closely related to China’s unique governance system, especially the tussle of power between the central and local governments. Dr Min Hu says it is important to encourage regional authorities to draw up targets that are stricter than those set by the central government. She says that only when the local goalposts are higher can those policies from the central government be realised. She adds:

But Ma hopes the loopholes can be closed

8613371530291

8613371530291