overshot water wheel efficiency pricelist

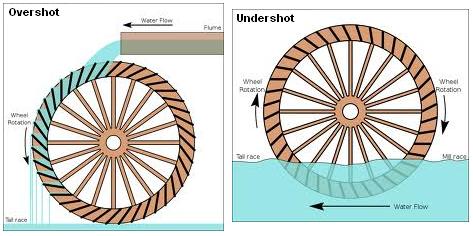

The overshot wheel is the most common wheel seen in North America. It is a gravity wheel. This means that it harnesses the force of gravity acting vertically on the water as it travels from the top to the bottom of the wheel. Properly designed for a particular site, and correctly timed, an overshot The overshot wheel is most effective when it turns as slowly as possible and can still handle the total flow of water available to it. The optimal rim speed should be only about 3 feet per second. The larger the wheel the slower it will need to turn. The incoming water must be traveling about three times the rim speed of the wheel so that it can fill the buckets effectively. This requires a foot or more of head above the wheel, usually controlled by a gate.

When the head, or fall of water was not sufficient for a large diameter overshot wheel, the breast wheel often is used. This is halfway between the overshot and undershot wheels. Water strikes the buckets of the breast wheel about midway between top and bottom, using the weight of the water for a 90 degree segment of arc. Their efficiency is far less than the overshot, which uses the weight of the water for a full 180 degrees.

This type of waterwheel relies on the flow of water, coming along the base flowing at a good rate of speed to push or thrust the waterwheel. This type of waterwheel is used on mills built on rivers or streams that do not have any height or (head). Undershot wheels are normally narrow and have to have the channel walls very close to the sides of the wheel to maximize the flow of water to pass through the wheels to generate power. This type of wheel is generally the least efficient type of wheel - usually in the 30-50% range. The exception to this is the Poncelet wheel that can get up to 80% efficiency if the channel is properly constructed and the buckets are designed right.

This type of waterwheel relies on the flow of water, generally in an open stream. This type of wheel is generally the least efficient type of wheel - usually in the 30-40% range. The exception to this is the Poncelet wheel that can get up to 80% efficiency if the channel is properly constructed and the buckets are designed right.

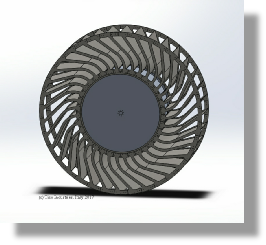

Many micro hydro electric generation strategies have evolved in recent years. Helical Ribbons, Under Water Blade Turbines, Tide and Wave action mechanical generators. Our approach is to simplify sustainable micro hydroelectric water wheel construction and improve the efficiency of energy generation. Our recent association with Ticho Industries in Italy has produced a new form of micro hydro waterwheels with a high efficiency electric generator mounted safely on the axle completely within the water wheel structure. This design simplifies micro hydro water wheel design for optimal water flow location mounting, system longevity, ease of maintenance and simplified electro mechanical connection. Our new design was created for city and rural stream based flows - including the outflows from major hydro electric dams, major navigation and irrigation dams, manufacturing and water treatment facilities.

In the Results section, the achievable power and related electromechanical equipment costs were estimated, both for the Turgo turbine and for the optimized water wheel, showing that the Turgo turbine is more expensive, but more powerful. In this section, the obtained results are discussed with the aim of providing useful considerations to support techno-economic choices in this context.

For example, the Authors are aware of the case of Gragnano mill (Italy), where the material costs related to 2 VAWWs, 2 millstones, 1 hopper and civil works were quantified in 40,000€ (pers. comm. of Pietro Ingenito). The costs incurred in 2001 by Mulino di Bobbio Pellice (pers. comm. of Emanuela Genre) were 16,000,000 lire, including the restoration of the mechanical equipment (excluding the overshot water wheel) and the instrumentations (millstone, transmission equipment, drive belt, sifter and elevator). The retrofitting of the overshot wheel costed 12,000 € (D = 2.6 m, B = 0.9 m) in 2003. The costs incurred in 2004 by Mulino Cornaleto (pers. comm. of the owner Michele Nardi) related to 2 VAWWs, 2 hoppers and restoration works (made in order to preserve the original stone structure) were quantified in 200,000€ (with a contribution from the Italian Soprintendenza equal to 1/3 of the total). The cost to rebuild the 2.1 m long shaft of the VAWW of Mulino Parrini (Italy), with a VAWW 1.4 m diameter, was 800 € (pers. comm. Giovanna Recati).

However, within the scope of this study it is not possible to carry out a complete cost-benefit analysis, since the above listed costs and benefits are site specific. Nevertheless, a discussion based on the obtained results of the electromechanical equipment can be carried out, for example, estimating its payback time in case of electricity sale. To calculate the payback time, the Italian tariff of 0.155 €/kWh can be assumed. The annual economic income from the electricity sale also depends on the annual operating hours. The annual operating hours highly depend on the water level and flow variation: flow variations would greatly affect the water wheel performance, while for Turgo turbines, that have a proper regulation system, the functioning is much more homogeneous. Furthermore, in certain cases, due to the low power output of water wheels, water wheels may not be suitable for electricity generation. However, 4,000 h per year for Turgo turbines (at the average flow) and 2,000 h per year for the water wheel can be assumed. With these assumptions, the payback time of the electromechanical equipment would be 13.6 years and 3.9 years for Turgo turbines and optimized water wheels, respectively (calculated assuming only the costs estimated in this work, thus excluding maintenance, installation and transport costs, that are site specific). Therefore, although it is not possible to know exactly the operating hours, since they are site specific, the order of magnitude of the calculated values can be considered reasonable to provide realistic discussions. In this assessment we did not consider the other costs and additional economic incomes, thus the estimated payback time has to be strictly interpreted as the time required to pay the electromechanical equipment by the sale of electricity. The cost of Turgo turbines may reduce in the near future due to the development of novel manufacturing processes and innovative and lighter materials, e.g. composite (Quaranta and Davies, 2021).

Finally, Table 1 presents a general overview of average results for the Turgo option, the optimized water wheel and, furthermore, for a traditional (not optimized) water wheel, assuming a traditional water wheel efficiency of 29% with straight blades (Pujol et al., 2015) and a global plant efficiency of 20%. The same cost of the optimized water wheel was assumed, although it may be slightly lower due to the straighter blades. The Turgo turbine is the option to maximize the long-term profit, despite the higher installation cost, while the optimized water wheel is the optimal solution when the scope is to reduce installation costs and payback time of the equipment.

The results discussed in this work refer to water mills equipped with optimized water wheels, e.g. following the guidelines described in recent papers (e.g. Pujol et al., 2015). With an optimized water wheel, the production of grinding grain per unit time can increase on the order of, at least, 60% (from 10 to 13 kg grains per hour to 16–20 kg grains per hour), with respect to an original water wheel. Although it is lower than that obtained with modern turbines (25–30 kg grains per hour), it seems very promising in terms of the high adoptability rate of the proposed upgrading (Pujol et al., 2015).

Water wheels are generally perceived as being inefficient energy converters which belong to the past, with no role for the future. But as Gerald Müller, Klemens Kauppert and Rüdiger Mach explain, they can actually be efficient and cost-effective in low head micro hydro applications

IN EUROPE, a large number of low head micro hydro power sites (head = <5m, power = <100kW) exist. Water power was a prime power source during the industrial revolution and thousands of water mills were built at low head sites. Today however, the large majority of such hydro power sources is not exploited due to the lack of a cost-effective hydraulic power converter. Recently, a number of developments appear to have opened up the possibility to generate electricity economically at low head sites. These developments include the two oldest hydraulic machines, namely water wheels and the Archimedian screw - the latter working in reverse as a power source rather than as a pump.

Water wheels are today often considered to be relics from the beginning of the industrial revolution; romantic but inefficient hydraulic machines made of wood and belonging to the past. It is generally believed that turbines are much more efficient than water wheels and subsequently took over their role as hydraulic power converters. The statistics however show a different picture. In Bavaria - a German province with an area of 70,500km2 - there were 7554 operational water wheels counted as late as 1927, with power outputs ranging from 0.75 to 75kW. In the middle of the 19th century, a high stage of development was reached when Zuppinger designed the most modern and efficient water wheel. Engineers, manufacturers and mill owners must have regarded water wheels as commercially interesting power sources. During the 1940s however, virtually all water wheels seem to have disappeared.

Today, some companies in Germany (Bega, Hydrowatt) and the US (Water Wheel Factory) are again manufacturing water wheels for electricity generation. The performance characteristics of such wheels still appear to be largely unknown. Assessment of the available power potential, comparisons with other turbine types such as the Kaplan or the Ossberger (crossflow) turbine, and even the determination of optimum operating conditions for water wheels, relies on estimates.

"Modern" water wheels, ie water wheels built using scientific principles, are made of steel and employ only the potential energy of the water since in low head flows the potential energy exceeds the kinetic energy of the flow by far. These water wheels can be divided into three fundamental types:

Water wheels were, in the large majority of cases, used to drive machinery and reached efficiencies of 75-89%. This development seems to have subsequently been forgotten.

In Karlsruhe, Germany, a small non-profit research company (IFMW - Institut für Forschung und Medien im Wasserbau) has been set up which specialises in hydraulic engineering research, and in particular in the development and promotion of low head hydro power. Within the company, a very detailed literature and market review on water wheels was conducted in order to assess the suitability of water wheels for electric power production. Since only over and undershot wheels are currently built, the discussion will be limited to those two types.

The overshot wheel receives its feeding water at the top of the wheel, catches the water in buckets or "cells" and releases the water at the lowermost possible elevation. In order to make maximum use of the energy contained in the water, the cells are shaped so as to receive the water at its natural angle of fall and then to retain it as long as possible.

Some measurements of the performance characteristics of overshot wheels were conducted in 1928, as shown in the figure below. It was found that the efficiency of a water wheel reaches 85%.

These measurements were taken with a gear ratio of 1:25, so that the shaft efficiency will probably lie close to 90%. In addition, very high efficiencies are maintained over a wide range of flow rates.

The undershot wheel was developed for the utilisation of very low heads from 0.5-2m. Whereas in ancient times the kinetic energy of the flow was utilised with a paddle-type wheel, "modern" undershot wheels built after Zuppinger"s design employ the potential energy only. The figure below shows a Zuppinger wheel with the typical "backwards" inclined curved blades.

Wheel diameters range from 4-7m, with head differences from 0.5 to 1.5m. The blades are arranged in a way so as to avoid losses at the water entry, then gradually reduce the head of water in each cell and finally to discharge the water, again with a minimum of losses. The wheel blades are curved to allow for a gentle decrease of the water level from upstream to downstream, and to minimise losses at the downstream end. In an engineering textbook from 1939 it was stated that efficiencies of 76% can be guaranteed for properly designed undershot wheels.

Recently, the undershot wheel has also experienced a small renaissance. Hydrowatt has built and installed 15 Zuppinger wheels over the last nine years, with diameters ranging from 4-7.5m, and widths of 0.5-3m. Hydraulic heads utilised ranged from 1-2.2m, with typical flow rates of 1.5-3.1 m3/sec, giving power outputs from 4-45kW of electrical power. The overall efficiency (from hydraulic power available to electric power out) was estimated as ranging from 60 to 65%.

In the UK, many smaller streams were made navigable by building weirs, many of which still exist. Generally, the head differences were in the range between 1.2-1.8m. The undershot wheel may offer a possibility to produce electric power from such weir sites. The picture below shows a typical weir situation (Eel weir on the Lagan river in Northern Ireland) with a virtual water wheel inserted. The water wheel actually fits into a "natural" environment very well, indicating that a modern machine can become a visually attractive feature too.

The Archimedian screw has been known since antiquity as a simple machine for the lifting of water. Today, Archimedian screws are still in widespread use as pumps for sewage, grain and so on. It has the advantage of being a very simple machine, with only one moving part and two bearings. It was however only recently noticed that the screw could also - in its reverse role - be employed as energy converter, termed hydraulic screw. Large scale experiments with a hydraulic screw of 8.6m length and 2.35m drop were conducted at Prague Technical University in the Czech Republic in order to assess the performance of the hydraulic screw in its power generation mode.

The screw shown in the picture above was designed for a maximum flow rate of Qmax = 0.35 m3/sec. In experiments, it reached an efficiency of 70% for Q/Qmax = 0.4, and 80% for 0.6 < Q/Qmax < 1.0. The screw rotates at 53rpm, so that fewer gear ratios than for a comparable water wheel are required to achieve the speed necessary for electricity generation. To the author"s knowledge, six hydraulic screws have been installed already. Some design guidance for hydraulic screws, based on the design experience with screw pumps and generator experiments, is also available.

The economics of micro hydro converters are a function of variable boundary conditions such as electricity prices and so on. In Germany, overshot water wheels are currently built (including installation and grid connection) for 4360-4850 US$/kW. Undershot wheels cost 7760-9700 US$/kW, Archimedian screws approximately 8250-8730 US$/kW installed capacity. For comparison, low head Kaplan turbines cost 14500-15500 US$/kW. Although water wheels and the Archimedian screw have significant cost advantages over turbines, micro hydro installations are economical only if the owner uses the generated electricity at least partially, such as for a small business. Assuming 50% of self use, 6000 hours of operation per year at nominal capacity, a small business electricity price of 11 c/kWh and a price of 7.3 c/kWh for electricity fed into the grid, the following pay back periods apply:

The general perception amongst the public as well as many engineers is that water wheels are inefficient energy converters and belong to the past. Water wheels, and in particular the overshot variety, are however very efficient and cost-effective energy converters for low head micro hydro power applications. Today, the wider application of water wheels seems to suffer from a lack of information on water wheels, the lack of any design guidance and - possibly the most important aspect - the lack of actual data about the performance of such wheels.

Apparently, no performance data at all exists for undershot wheels, whereas some information is available on overshot wheels in old reports. IFMW Karlsruhe is currently conducting a detailed review and analysis of the experimental data available on overshot wheels with a view to application of such wheels for electricity generation.

The determination of performance characteristics for overshot wheels, and the publication of such data, will be the next task of the company, followed by a detailed evaluation of undershot wheels.

Ecological aspects are today a major issue in the design of hydro power installations. Both the water wheel and the Archimedian screw are considered to be very fish friendly because of the large compartments for the water and the slow speed, even for long fish like eel, thus giving them a considerable advantage over the fast rotating Kaplan turbines.

Back in 1947, Popular Science printed a five-part article by C.D. Bassett that very concisely sketched out every step necessary for the establishment of a small water-power plant on a farm or homestead. That information is still just as valuable today for many of MOTHER’s readers as it was 30 years ago . . . and that’s why THE MOTHER EARTH NEWS asked for — and received — permission to reprint the whole series as a two-part article in MOTHER NOs. 13 and 14. The Popular Science material was also included — by permission — in THE MOTHER EARTH NEWS Handbook of Homemade Power.

If any of the terms or ideas in the accompanying article are unfamiliar to you, then, you have three choices: [1] You can trot on down to your local library and exhume the old, original C.D. Bassett articles from the 1947 issues of Popular Science, [2] you can order out MOTHER NOS. 13 and 14 at $2.00 apiece from the ad on pages 114-115 of this issue, or[3] you can get your own copy – $1.95 plus 75¢ shipping and handling — of The Handbook of Homemade Power by using the MOTHER’s Bookshelf ad on pages 174 -177 of this issue. Any way you go about it, you’re going to learn all you need to know to lay out, install, and operate your own water-power system. All you’ll need to add to this information is a free-flowing stream . . . and you’re in business.

One final note: The following article describes a homemade overshot water wheel set up to do only one thing . . . pump water from a spring to a set of farm buildings 100 feet above. If you’re more interested in learning how to use the same kind of wheel to generate electricity, see the article, schematic drawing, and photographs of Thomas Oates’ water-wheel powered DC electrical system in MOTHER NO. 24. That piece was also reprinted in The Handbook of Homemade Power. — The Editors.

One very successful example of this “back to basics” trend is the water wheel-powered water pump now in operation on the Robert Wooding farm near Halifax, Virginia. The pump-powered by a home designed and home-built 6 1/2-foot, steel water wheel which, in turn, is spun by water from a stream on the family farm shoves 1,440 gallons of pure spring water 100 feet uphill every 24 hours. And, since the system was set up, it hasn’t cost the Woodings anything for its tireless round-the-clock operation . . . except a few cents for lubrication.

“There are three things I especially like about my wheel,” says Bob blooding. “One, unlike the hydraulic ram pumps featured several times in MOTHER, it doesn’t use gallons and gallons of our drinking water just to pump a few gallons up the hill. Two, the overshot design of our wheel makes very efficient use of the small stream we tap for power. And, three, there’s not a whole lot of banjo work to a rig like this once you’ve got it going. We spent a little time and money setting our system up, to be sure, but it’s been practically maintenance-free ever since. About all we do is give its bearings a shot of grease two or three times a year.”

The Woodings were fortunate enough to have a picturesque stream on their property (the first and most obvious requirement for any water-power system!) . . . but that’s as far as their luck went. At no single spot along the creek was there enough “fall” to turn the 6 1/2-foot overshot wheel that Bob figured on installing.

Fall, as the name implies, is the amount of vertical distance that running water drops as it moves down a stream (if there were no fall at all, the water — obviously — wouldn’t run and the stream wouldn’t be a stream . . . it would be a slough or a lake).

The ideal location, of course, for an overshot water wheel (which must be positioned in a stream at a spot where the water abruptly drops at least as far as the wheel is tall) is a natural rapids or waterfall. If, like the Woodings, you find yourself working with a stream that has no such abrupt natural drop, however, you’ll have to do what the Woodings did: Build your own man-made waterfall . . . which, as we all know, is commonly called a dam.

(NOTE: The reprinted series of five articles from Popular Science mentioned at the beginning of this piece contains everything you need to know to calculate the flow and call of a stream, design several kinds of dams, build and install an overshot wheel, and otherwise fabricate and operate a farm- or homestead-sized water-power system. — The Editors.)

“We needed about a seven-foot fall for our 6 1/2-foot-tall wheel,” Bob blooding remembers, “so we built a three-foot-tall dam . . . and then flumed the water from the top of that dam to a spot 120 feet further downstream where the creek’s banks were an additional tour feet lower. The dam’s height of three feet plus the additional four feet of drop we picked up by running our flume that tar added up to the seven feet of fall, or head, that we needed for our wheel.”

The Woodings’ flume is a combination of approximately 85 feet of four-inch aluminum pipe feeding into an additional 46 1/2 feet of wooden trough measuring six inches deep by six inches wide. (The aluminum pipe, which extends about a foot and a half into the trough, can be lifted out and set into a curved metal deflector which routes its water back into the stream whenever the Woodings want to stop the wheel.)

Traditional flumes for homestead water wheels, of course, were of all-wood construction. But Bob Wooding decided to use rot-free, corrosion-free aluminum pipe for the first two-thirds of his wheel’s feeder line, where the flume had to extend into the water and then run underground. The pipe’s inlet is covered with a screen to keep the line from becoming clogged with misguided leaves, turtles, and crawfish. Care was also taken to position the opposite (wooden) end of the flume so that its discharge of water would hit the exact top-center of the overshot wheel.

Although the blooding family’s water system for their house, stables, and swimming pool is powered by the stream on their farm . . . the actual water which flows through that system comes from a clear, cool, pure spring. This spring, too (just like their dam), is located about 120 feet from the overshot wheel and pump that is the heart of the whole hookup. So, in addition to the flume which carries the “driving” water from the dam to the wheel, another one-inch pipe was laid to carry the “driven” water from the spring to the pump that is installed next to (and driven by) the wheel.

Luckily for the Woodings, the spring water’s temperature stays 52 degrees Fahrenheit year round. Merely by laying this feeder pipe so that it has a continuous slight grade from the spring down to the pump a few feet below, then, the family has been able to keep their water supply from freezing in the winter without going to the trouble of burying the pipe below the frost line.

When you buy a manufactured water wheel, a large portion of the purchase price goes to pay for the equipment’s design. It follows, then, that you can save yourself a sizable chunk of cash by working up the specifications for your own wheel . . . and that’s exactly what Bob Wooding did.

Actually, this isn’t as difficult as you might think. To extract maximum power from any given flow of water with an overshot wheel is largely a matter of calculating the proper depth and angle of the buckets placed around the wheel’s rim (ideally, each bucket must be completely filled at top center and then carry its load of water without spilling a drop until just the instant it passed bottom center . . . but anything even remotely approaching this ideal will handle the job satisfactorily in most homestead applications).

(EDITORS’ NOTE: If you scale up the drawings shown here and use them to construct a wheel ranging anywhere from two feet up to 20 feet in diameter — and if you work carefully and in a craftsman-like manner — the chances are good that your finished wheel will work well enough to make you pretty dang proud of yourself. If you really want to go for the finer points of maximum efficiency, however, you can work from the more detailed dimensions and angles given in the full-page drawing of an overshot wheel on page 31 of MOTHER N0. 14.)

After drawing up his design (complete with “dribble” hole in the bottom of each bucket, so that the wheel is self-draining when not in use!), Bob had the individual parts for his water wheel prefabbed by the Carolina Steel Company in Greensboro, North Carolina. A Richmond, Virginia representative for the firm says that the 3/16 inch steel plate used in the 980-pound assembly’s 37 eight-by-twelve-inch buckets, its five-inch-wide rim, and its one-foot-wide sole plate would currently cost about $130. You can add on another $70 for burning, forming, and welding the metal. (These prices, of course, will vary in different parts of the country and — as time goes on — are sure to escalate right along with the price of everything else.)

The hubs for the Wooding wheel were pretty much “Chinese copied” from the hubs manufactured years ago by the now-defunct Fitz Water Wheel Company of Hanover, Pennsylvania. Bob had them cast at a local foundry from a wooden pattern that he made himself, and the materials and labor for the raw castings set him back only $25. A nearby machine shop then bored out the hubs on a lathe, cut keyways into the bores, and made up the pair (each half of the set contains six 3/8 inch by 2 inch spokes) of spokes for the wheel . . . all for only $60 complete.

Once he had all the components for his wheel prefabbed and in hand, there was nothing for Bob Wooding to do but assemble the power unit. “I used calipers to measure and remeasure the spaces around the rim for my buckets until I had them exact to the width of a pencil mark,” Bob says. “Then I tacked the buckets in place all the way around and rechecked everything before I finally welded them in permanently. If you try to finish-weld each one as you go without tacking everything together first, you know, you can get off kilter and warp the whole wheel.”

Every one of the six “ears”, or extensions, on each of the two hubs has a recessed area 3/8 inches deep by two inches wide by four inches long on its inside surface for a spoke to set into. This end of each spoke is held firmly in place with two 7/16 inch galvanized bolts, nuts, and lock washers. The other ends of the spokes are welded to the outside faces of the wheel’s rim . . . as you can see in one of the accompanying photos.

It should also be pointed out that the distance (16 inches) between the two hubs is four inches wider than the distance (12 inches) across the buckets on the rim. This “dish” effect — so typical of the Fitz wheels of years ago — adds a great deal of strength to the completed wheel . . . without adding any additional weight.

The finished wheel was hoisted with a front-end loader, hauled to the foundation that had been poured for it, and gently eased down until the pillow block bearings on its two-inch steel shaft could be bolted into place. A few small pieces of metal were then welded into some of the buckets to balance the completed assembly, and the whole wheel was given a primer coat of zinc chromate and a finish coat of black enamel.

As water pours down over one side of the mounted wheel and turns it, the spinning of the wheel is converted to an up-and-down pumping motion by an eccentric arm attached to the assembly’s two-inch-thick main shaft. This “arm”, to be truthful, is not really an arm at all . . . but simply a spot one and a half inches off center on the face of a 15-inch gear salvaged from a local junkyard. The spot has been drilled and tapped to accept a threaded mounting pin for the lower end of a long white oak connecting rod.

As the water wheel’s main shaft rotates, then, the 15-inch gear attached to it also rotates smoothly. This causes the eccentric pin fastened to the face of the gear to revolve around and around in a three-inch arc. Which, in turn, causes the guided white oak connecting rod that rides the pin to pump up and down with a three-inch stroke.

The upper end of the connecting rod (think of it as the hand holding the handle of an old-fashioned “armstrong” water pump) is bolted to a cross-arm that runs across the top of a reservoir and is secured to a red cedar post on the other side so that it can hinge up and down. And in the middle of that cross-arm — just off center in favor of the water wheel — is attached a cylinder rod which runs down to a cylinder pump that is firmly bolted to the bottom of the reservoir.

And that’s all there is to the Wooding stream-run, spring-fed water system. Water from the spring 120 feet away runs a couple of feet downhill to fill the cement reservoir. At the same time, a great deal more water from the dam — also about 120 feet away but in a slightly different direction — flows through the flume and pours down over one side of the 6 1/2-foot water wheel, causing it to turn. And, as the wheel turns, the pump in the reservoir pumps . . . which forces the fresh spring water 100 feet uphill (through a line buried beneath the frost line) to a 500-gallon storage tank which stands near the blooding house. And, from that tank, the spring water is then gravity-fed to the house, stables, and swimming pool on the blooding property.

And there’s something rather nice about the whole arrangement. The “splash-splosh” of the water wheel is far more relaxing and natural than any huffing-puffing engine . . . and a lot less expensive to operate year in, year out than any quiet but increasingly costly electric motor. Every bit of technology used in the Wooding setup, of course, has been around a long, long time . . . and a lot of other farmsteads in the country could put a variation of the same idea into use right now.

The path that the water takes through a turbine and the general layout is often used for classification, like tangential-flow, radial-flow cross-flow and axial-flow. Below are the various categories of ‘water driven prime mover that can be used to convert the ‘potential energy’ in a river or stream into usable ‘mechanical’ or ‘electrical’ energy. This section continues with information on what types of turbine are suitable in various sites and applications.

Gravity devices are those where any kinetic energy present at the entry of the device is either minimal or lost in turbulence and does nor contribute measurably to the output of the device. Such devices include most waterwheel types, Archimedes screws (where the outer case rotates with the flutes); Hydrodynamic screws (as used for sewage pumping and now being used in reverse as low-head prime-movers); Norias (more commonly used for raising water) and consist of a string of buckets like an overshot waterwheel attached to form a chain, and positive displacement devices or hydraulic engines.

Impulse turbines are those where the potential energy in a ‘head of water’ is largely converted into kinetic energy at a nozzle or spout. The simplest of such devices is the Gharat or Norse Wheel (where the conversion to kinetic energy takes place in an open flume). The more conventional devices harness the potential energy in a pipeline or penstock that terminates in a nozzle. The flow path through the turbine is usually used to describe the specific device, namely, tangential-flow, radial-flow, cross-flow, axial-flow or mixed-flow. Specific turbine designers have been associated with most of these devices, though confusion can result because they often designed several different types of device (The Pelton Waterwheel Company also made cased reaction turbines, Herschel pre dates Jonval’s patent that was the precursor of the Turgo Impulse wheel, a single nozzle version developed by Gilkes. Donat Banki, a Hungarian was also making cross-flow turbines many years before Mitchell and Ossburger came on the scene.

Reaction turbines are those where the turbine runner is usually completely flooded and the transfer of energy from the water to the turbine runner is achieved by a combination of reaction and/or lift. Some designs of cross-flow turbine in common use a combination of impulse and reaction. Reaction turbines have had a more complex development, with many designers and factories adding features such as movable ‘wicket gates’ that resulted in Francis’s name becoming the tag by which this group of turbines are now known. The Kaplan turbine developed in the 1930s is a sophisticated variable geometry version of the ‘propeller turbine’ that as its name suggests is similar to a ship’s propeller in a housing. Halfway between these types is the single regulated propeller turbine, where either the runner blades or the ‘guide vanes’ (wicket gates) are adjustable.

Free-stream devices encompass large slow running wheels and turbines, some of which are being tried out for marine energy applications. Like wind turbines, the power delivered increases as a cube of the velocity, such that a doubling of the velocity gives an eight fold increase in power output. The devices themselves are very large and slow running and only have very specialised applications for extracting small amounts of power from bank-side locations on very large rivers.

High head sites with over 20 metres of fall, where the water is conveyed directly to the turbine in a pipe (penstock) or via an open canal followed by a piped section, generally use impulse turbines. The reason is that high head sites are usually subject to significant changes in water flow and reaction turbines like the Francis are not able to cope with such variations. Silt in the water can also cause a lot of damage to Francis turbines that is expensive to repair.

One of the most successful high head turbines was developed in California during the gold rush from a device referred to as a ‘hurdy gurdy’ that was basically a cartwheel with buckets around the periphery. A carpenter by the name of Lester Pelton came up with the now familiar double bucket shape and went on to found ‘The Pelton Watewheel Company’ of San Francisco. The bucket design was later improved by Doble who joined the company as an engineer in 1899. Doble’s improvement is the central cut-out in the bucket that prevents the water jet from first striking the back of the bucket and wasting energy. www.oldpelton.net. Today, similar machines are operating from over 1000 metres of fall and generating up to 100MW of power.

A simple weir is all that is required to divert the stream into the penstock (pipeline) via a de-silting chamber to remove any sand. Water storage may be included if the terrain allows and if it is advantageous to generate more power for short periods or where it is necessary to store water for generation when flows are very low. A low-pressure pipe or open canal may also be used to reduce to overall cost if it allows a short steep decent to the powerhouse using less high-pressure pipe.

Pelton turbines are efficient over a very wide range of flows but at lower heads the speed is too low for belt drives, so we reduce the pitch circle and modify the bucket shape to increase the specific speed. The jets may have plain nozzles or adjustable spear valves to adjust the water consumption to the available stream flow. It is usual with larger machines to have ‘deflectors’ that divert the water away from the runner for controlling the speed without altering the water flow. They can also be used for emergency shutdown.

Turgo Impulse turbines, the name given by Gilkes of Kendal, is a ‘jet supplied impulse turbine’ that has its origins back in the early 19c when Herschel and Jonval and latterly Gunthers of Oldham made similar turbines. The ‘Turgo’ with one or more jets is often used for lower heads where it is necessary to keep the shaft speed up for direct driving the generator. A two jet ‘Turgo’ runs at about twice the RPM of an equivalent four jet pelton, and the runner is significantly smaller but the efficiency is a little lower.

Crossflow turbines have become popular in recent years, not least because of the widely mistaken belief that they are easy to make. They may be easy to make badly but only a handful of companies manage to make good ones, and even then there is a significant penalty in terms of efficiency and blade fatigue is still a problem. Because of this problem, the few cross-flows we have built, all have cast runners and as a result we have not suffered blade breakages. For those that still want a cross-flow design, we can supply them either in our ‘Agricultural’ range or as an option in our ‘Hillstream’ range for medium heads

Francis turbines are widely used for larger hydroelectric projects where high efficiency and small size are important. The part flow performance and relatively high cost means that they are less common on small schemes less than about 100 kW. We rebuild this type of turbine as and when the need arises.

For thousands of years waterpower has been harnessed for milling and pumping water. In the Developing World many are still in daily use, but in Western Countries they have usually fallen into disrepair as a result of competition from diesel and electric power. In the U.K. there were over 70,000 working mills at the end of the 18th century and now there are a few hundred. These mills fall into a number of categories that will determine their suitability for redevelopment.

The waterwheels that were used on these sites in the U.K. are usually of the Roman or horizontal shaft type, though the vertical shaft type is much more common in Mediterranean and Asian countries. Depending on the fall of water available, the horizontal wheels are classified into ‘Overshot’, ‘Breast-shot’, ‘Back-shot’ and ‘Under-shot’. With the exception of projects to restore a mill to its original design, or where the visual appearance is important to maintain, only the overshot wheel is suitable for a new power generation projects.

Overshot waterwheels are the most fish-friendly and able to handle leaves and sticks. A similar device is the Noria or chain wheel, which has the disadvantage of potential more maintenance, but it runs faster, is more efficient and easier to install than an overshot waterwheel.

The power available is a function of the head and flow so building a large wheel will only increase the cost and reduce the shaft speed but not increase the power. Major components in the cost are the primary gearbox and the material required in the construction of the wheel itself. We are happy to build any type of waterwheel, but the cost is likely to be significantly greater than that of an equivalent turbine, when you take the gearing and installation costs into consideration. There are no short cuts with waterwheels and the engineering has to be good, on account of the high torque in the low speed drive.

Mills with ponds are seldom suitable for redevelopment for anything other than a few kilowatts because the water flow is obviously too little to sustain the mill on a continuous basis, and it is much too expensive to install a wheel or turbine that can only be operated for a few hours a day. In some cases the ponds were only used in the summer months when the water was low, but today we are looking to the higher winter flow for the bulk of the power that can be used for heating. There is always a loss of head into and out of the pond, but this may be recoverable with a turbine installation.

Mills with leats, lades or channels take their water from a water course along the side of a valley at a gradient that is usually less than one in five hundred. At a suitable point when enough fall can be achieved in one place, the mill is built. The only limitations to future development are the actual head and flow available. Since there was a mill there anyway there should be enough power for domestic purposes. Improvements to the leat and head are usually possible but are very site specific. Modern mini excavators make leat widening and maintenance much easier than when the mills were first built.

Mills on weirs or with short wide diversion channels present the most difficult challenge for the developer. The available head may only be a metre or so and the flow required to generate useful amounts of power will be several cubic metres of water per second. The undershot waterwheels that were originally used at these sites are totally redundant on account of their high cost and low efficiency. The exact layout of the site becomes increasingly important with the lower falls, because access for excavators and to install the large items of equipment is more difficult.

Open flume installations are the most usual for the very low head sites, and employ fixed geometry propeller turbines on account of their simple construction and high ‘specific speed’. The more complex variable ‘Kaplan’ type turbines are not economic for these small schemes and it is easier to achieve ‘flow control’ by installing more than one machine or by running until the water has fallen by say 100mm and then switching off automatically until it has come up again. This latter system can be used for heating

Tubular turbines of the propeller type can be used for mill sites with a higher head, typically those that originally employed ‘Overshot’ waterwheels. Many different arrangements are possible to suite existing civil works but the main compromise arises from their inflexible performance. If the mill is only extracting a small percentage of the available water from the main river, then there is no problem. If however the water flow reduces below that which is required to supply the turbine, either water storage, another smaller turbine or a change in turbine speed will be required.

Impulse turbines, like the ‘cross-flow’ are better suited to medium heads because the physical size and cost are out of all proportion, and the efficiency is severely limited by the loss across the runner itself. Large open-flume ‘Armstrong’ designs have lower losses and are smaller on account of the high percentage admission. No casing is required and in common with reaction turbines a draft tube may be employed to gain extra head or set the turbine above flood level.

Low cost open impulse turbineshave been developed by us, primarily for projects in the Developing World. Installed outside the mill house like a waterwheel, it is an economic alternative for smaller domestic sites here in the U.K. They cannot be used with a draft tube since the runner is open to the atmosphere but the installation and maintenance is much simpler. The valve control shaft is extended through the mill house wall to an operating lever on the ,inside or a simple open shoot conveys the water directly to the runner in the manner of the old ‘flutter wheels’ used in the USA in the 19c. Installation work is usually kept to a minimum and may be in an old waterwheel pit or even behind an existing wheel under the launder. A vertical shaft version like the Indian Gharat can produce considerably more power by increasing the entry area, whilst maintaining its self-cleaning characteristics.

Portable turbines are highly adaptable and be assembled on site in a few hours. Applications include ‘Rural Development’, camping and field hospitals. Typical outputs range from 200 watts to 50 kW. The inlet works are prefabricated and the pipeline is either flexible polyethylene or ‘lay-flat’ coiled pipe. The whole unit can be built into a trailer or air-portable unit for rapid deployment in the field. The buckets that are divided along their centre line by a splitter ridge, turn the jet of water that is directed at them, through 1800 so that the energy is transferred efficiently to the shaft.

Turbines that are suitable for a particular type of site and turbines that are suitable for particular type of application are referred to as ‘groups’. Hence you can have a group of ‘Hillstream’ turbines for upland sites, or a group of ‘Agricultural’ turbines for agricultural applications. The site may be defined topographically as an upland or ‘Hillstream’ site, or as a lowland or ‘Millstream’ site. Each of these groups I then divided into two sub-groups depending on the actual site layout and general features. The ‘Hillstream’ group is comprised of vertical and horizontal shaft impulse turbines that may be either direct drive, belt drive or overhung from the generator. The application for the plant may be to generate electricity, mechanically power machinery or pump water for irrigation or for a drinking water supply. The application will also have a bearing on the materials, the sophistication, the governing system and the general build.

A water wheel changes the energy of falling water into mechanical energy that can be used for machines. The water is directed into the wheel through a tube. The wheel is placed on an axle, which is connected by gearing with the machine it is to operate. There are two types of water wheels, vertical and horizontal. The vertical wheels has an overshot and a undershot. The overshot water wheel has buckets around its edge. Water is delivered to the top of the wheel. The weight of the water falling into the buckets makes the wheel turn. An overshot water wheel has a very good chance of working with a 80 percent efficiency rate. That means, it may turn as much as 80 percent of the energy of the water into mechanical energy. Though, its use is limited to making small amounts of power. The undershot water wheel is built so the water hits the blades at the bottom of the wheel. The power of the wheel depends on the speed of the water hits the blades. The undershot wheel has such a low efficiency that it is rarely used. Most modern water wheels are horizontal. A horizontal wheel rotates on a vertical shaft. It is driven by the force of the water hitting the blades on one side of the wheel. Horizontal wheels are very efficient if made correctly.

For my experiment I made an vertical undershot waterwheel. For the base of the waterwheel I cut off 8 centimeters of the bottom of a milk jug. Then out of the top of the jug I cut four triangles, four squares and four circles out for the fins of the waterwheel. After that I thumb tacked the 4 triangles to a cork. Put a hole at the end of each side of the cork and glued a skewer in each side for an axis. Then I cut a hole at each side of the base and put the skewers with the cork suspended in the middle. Then I put a 2 inch x 2 inch piece of clay shaped as circles on each side of the skewer. That’s how I got my waterwheel.

In my experiment I didn’t use electricity instead I measured the rate at which a water wheel lifts a weight. Doing this determined the speed at which the water wheel spins. For a weight I used a penny that was taped to a string which was wrapped around the clay.

8613371530291

8613371530291