overshot weaving tutorial quotation

I wove some samples and decided to make this for my scroll. The warp was handspun singles from Bouton. I wanted to see if I could use this fragile cotton for a warp. I used a sizing for the first time in my weaving life. The pattern weft is silk and shows up nicely against the matt cotton.

This illustration and quote are in The Weaving Book by Helen Bress and is the only place I’ve seen this addressed. “Inadvertently, the tabby does another thing. It makes some pattern threads pair together and separates others. On the draw-down [draft], all pattern threads look equidistant from each other. Actually, within any block, the floats will often look more like this: [see illustration]. With some yarns and setts, this pairing is hardly noticeable. If you don’t like the way the floats are pairing, try changing the order of the tabby shots. …and be consistent when treadling mirror-imaged blocks.”

The origin of the technique itself may have started in Persia and spread to other parts of the world, according to the author, Hans E. Wulff, of The Traditional Crafts of Persia. However, it is all relatively obscured by history. In The Key to Weavingby Mary E. Black, she mentioned that one weaver, who was unable to find a legitimate definition of the technique thought that the name “overshot” was a derivative of the idea that “the last thread of one pattern block overshoots the first thread of the next pattern block.” I personally think it is because the pattern weft overshoots the ground warp and weft webbing.

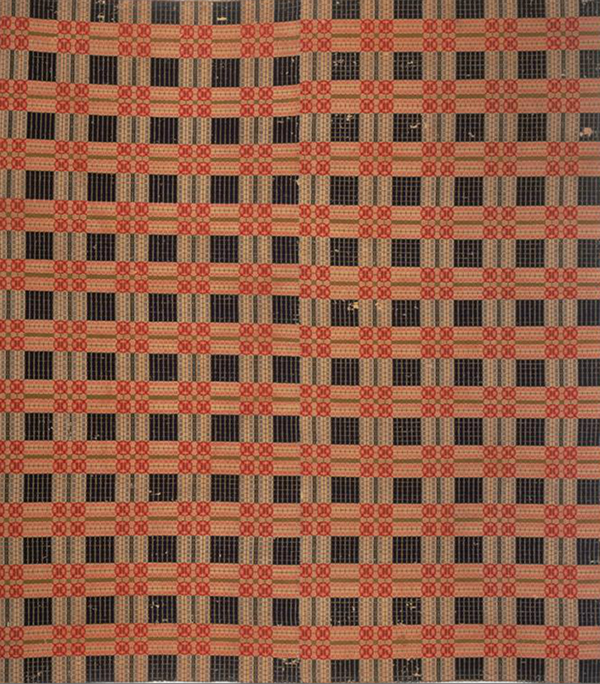

Overshot gained popularity and a place in history during the turn of the 19th century in North America for coverlets. Coverlets are woven bedcovers, often placed as the topmost covering on the bed. A quote that I feel strengthens the craftsmanship and labor that goes into weaving an overshot coverlet is from The National Museum of the American Coverlet:

Though, popular in many states during the early to mid 19th centuries, the extensive development of overshot weaving as a form of design and expression was fostered in rural southern Appalachia. It remained a staple of hand-weavers in the region until the early 20th century. In New England, around 1875, the invention of the Jacquard loom, the success of chemical dyes and the evolution of creating milled yarns, changed the look of coverlets entirely. The designs woven in New England textile mills were predominantly pictorial and curvilinear. So, while the weavers of New England set down their shuttles in favor of complex imagery in their textiles, the weavers of Southern Appalachia continued to weave for at least another hundred years using single strand, hand spun, irregular wool yarn that was dyed with vegetable matter, by choice.

And, due to the nature of design, overshot can be woven on simpler four harness looms. This was a means for many weavers to explore this technique who may not have the financial means to a more complicated loom. With this type of patterning a blanket could be woven in narrower strips and then hand sewn together to cover larger beds. This allowed weavers to create complex patterns that spanned the entirety of the bed.

What makes overshot so incredibly interesting that it was fundamentally a development of American weavers looking to express themselves. Many of the traditional patterns have mysterious names such as “Maltese Cross”, “Liley of the West”, “Blooming Leaf of Mexico” and “Lee’s Surrender”. Although the names are curious, the patterns that were developed from the variations of four simple blocks are incredibly intricate and luxurious.

This is only the tip of the iceberg with regard to the history of this woven structure. If you are interested in learning more about the culture and meaning of overshot, check out these resources!

The National Museum of the American Coverlet- a museum located in Bedford, Pennsylvania that has an extensive collection of traditional and jacquard overshot coverlets. Great information online and they have a “Coverlet College” which is a weekend series of lectures to learn everything about the American coverlet. Check out their website - coverletmuseum.org

Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women – This was an exhibit that traveled from Lowell, Massachusetts, Morehead, Kentucky, Knoxville, Tennessee, Raleigh, North Carolina, and ended at the Royal Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland. The exhibit contained a large number of overshot coverlets and the personal histories of those who wove them. I learned of this exhibit through an article written by Kathryn Liebowitz for the 2001, June/July edition of the magazine “Art New England”. The book that accompanied the exhibit, written by Kathleen Curtis Wilson, contains some of the rich history of these weavers and the cloth they created. I have not personally read the book, but it is now on the top of my wish list, so when I do, you will be the first to know about it! The book is called Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women and I look forward to reading it.

I still have his pillow in my studio (available in the Etsy shop, but I can"t say I"m upset that I still get to see it everyday). AND, there"s a tutorial for this on the YouTube channel! Tomorrow we"ll have an all new tutorial for you over on the YouTube channel at 2pm MST. A big order of velvet finally arrived today, and I"m SO excited to start putting together fibre packs, not to mention weaving with all these new materials that are sitting in my studio calling my name! Do you w

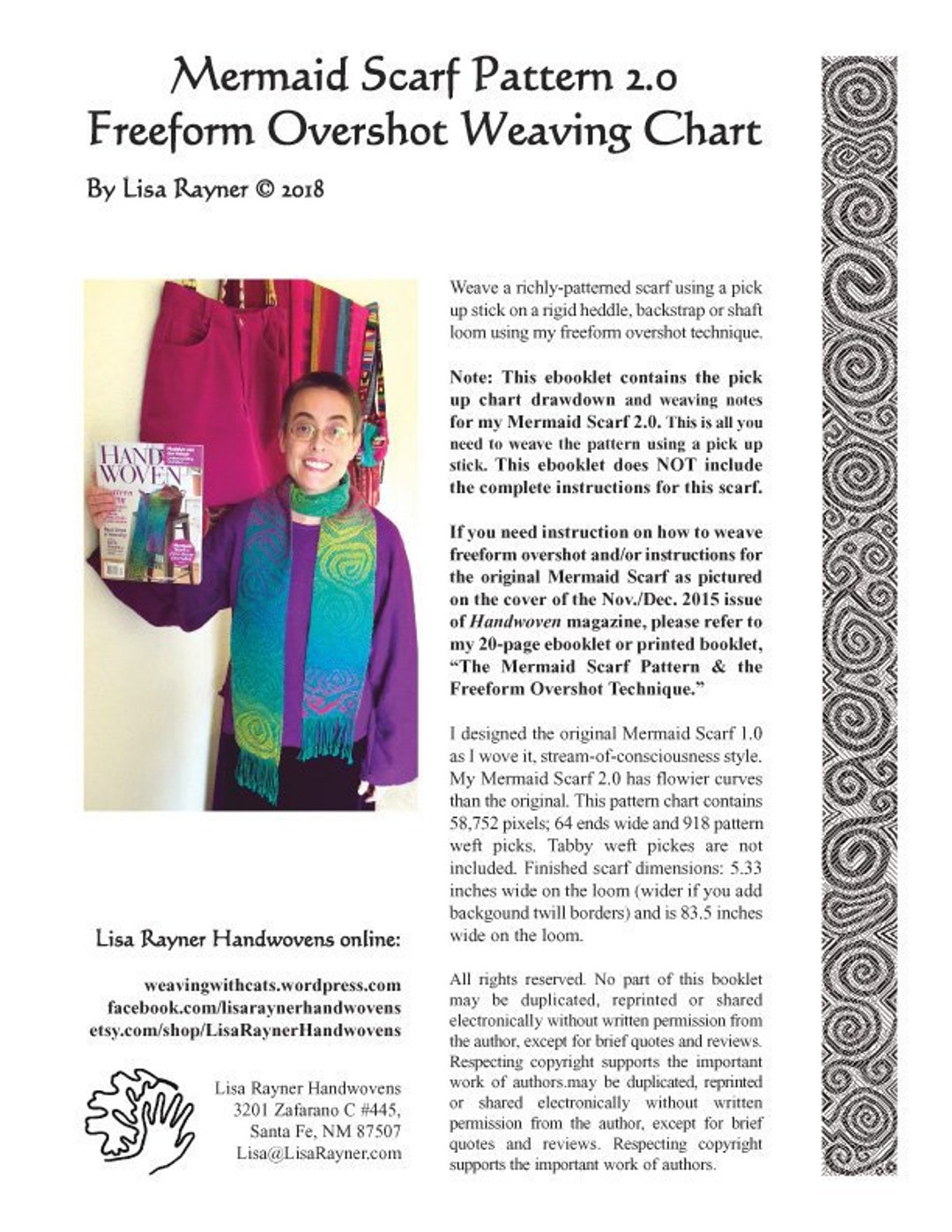

One of my favorite parts of working on my Ancient Rose Scarf for the March/April 2019 issue of Handwoven was taking the time to research overshot and how it fits into the history of American weaving. As a former historian, I enjoyed diving into old classics by Lou Tate, Eliza Calvert Hall, and Mary Meigs Atwater, as well as one of my new favorite books, _Ozark Coverlets, by Marty Benson and Laura Lyon Redford Here’s what I wrote in the issue about my design:_

“The Earliest weaving appears to have been limited to the capacity of the simple four-harness loom. Several weaves are possible on this loom, but the one that admits of the widest variations is the so-called ‘four harness overshot weave,’—and this is the foremost of the colonial weaves.” So wrote Mary Meigs Atwater in The Shuttle-Craft Book of American Hand-Weaving when speaking of the American coverlet and the draft s most loved by those early weavers.

Overshot, in my mind, is the most North American of yarn structures. Yes, I know that overshot is woven beyond the borders of North America, but American and Canadian weavers of old took this structure and ran with it. The coverlets woven by weavers north and south provided those individuals with a creative outlet. Coverlets needed to be functional and, ideally, look nice. With (usually) just four shaft s at their disposal, weavers gravitated toward overshot with its stars, roses, and other eye-catching patterns. Using drafts brought to North America from Scotland and Scandinavia, these early weavers devised nearly endless variations and drafts, giving them delightful names and ultimately making them their own.

When I first began designing my overshot scarf, I used the yarn color for inspiration and searched for a draft reminiscent of poppies. I found just what I was looking for in the Ancient Rose pattern in A Handweaver’s Pattern Book. When I look at the pattern, I see poppies; when Marguerite Porter Davison and other weavers looked at it, they saw roses. I found out later that the circular patterns—what looked so much to me like flowers—are also known as chariot wheels.

Weaving Overshot with Madelyn Van Der Hoogt DVD 92 Minutes From heirloom coverlets to dazzling contemporary household textiles and garments, overshot is one of the handsomest of weave structures. Whether woven in miniature on a towel or largescale in a rug, overshot is striking. In this video, Madelyn van der Hoogt teaches everything you need to know to explore the many faces of overshot. You"ll learn: How to read, weave, and play with overshot drafts Techniques to achieve balanced patterns Why halftones happen, and how you can use them in your designs How to spot and weave overshot in rosefashion and starfashion How to combine overshot threading with other treadlings, with spectacular results Ideas for playing with color and materials Along with Madelyn"s video workshop, this DVD gives you a printable booklet on overshot weaving, complete with planning exercises, reference materials, and overshot projects you can learn from and use. Order your copy of Weaving Overshot today

This post is the third in a series introducing you to common weaving structures. We’ve already looked at plain weave and twill, and this time we’re going to dive into the magic of overshot weaves—a structure that’s very fun to make and creates exciting graphic patterns.

Overshot is a term commonly used to refer to a twill-based type of weaving structure. Perhaps more correctly termed "floatwork" (more on that later), these textiles have a distinctive construction made up of both a plain weave and pattern layer. Requiring two shuttles and at least four shafts, overshot textiles are built using two passes: one weaves a tabby layer and the other weaves a pattern layer, which overshoots or floats, above.

Readers in the United States and Canada may be familiar with overshot textiles through woven coverlets made by early Scottish and English settlers. Using this relatively simple technique, a local professional weaver with a four-shaft loom could easily make a near-infinite variety of equally beautiful and complex patterns. If you’d like to learn more about overshot coverlets and some of the traditions that settlers brought with them, please see my reading list at the bottom of this article!

As it is twill-based, overshot will be very familiar to 4 shaft weavers. It’s made up of a sequence of 2-thread repeats: 1-2, 2-3, 3-4, and 1-4. These sequences can be repeated any number of times to elongate and create lines, curves, and shapes. These 2-thread repeats are often referred to as blocks or threading repeats, IE: 1-2 = block 1/A, 2-3 = block 2/B.

There are three ways weft appears on the face of an overshot cloth: as a solid, half-tone, or blank. In the draft image I’ve shared here, you can see an example of each—the solid is in circled in blue, the half-tone in red, and the blank yellow. Pressing down the first treadle (shafts 1 and 2), for example, creates solid tones everywhere there are threads on shafts 1 and 2, half-tones where there is a 1 or 2 paired with 3 or 4, and nothing on the opposite block, shafts 3 and 4. Of course, there’s not really nothing—the thread is simply traveling on the back of the cloth, creating a reverse of what’s on the face.

Because overshot sequences are always made up of alternating shafts, plain weave can be woven by tying two treadles to lift or lower shafts 1-3 and 2-4. When I weave two-shuttle weaves like overshot, I generally put my tabby treadles to the right and treadle my pattern picks with my left foot and my tabby with my right. In the draft image I’ve shared above, I’ve omitted the tabby picks to make the overarching pattern clearer and easier to read. Below is a draft image that includes the tabby picks to show the structure of the fabric.

Traditional overshot coverlets used cotton or linen for warp and plain weave wefts, and wool pattern wefts—but there’s no rule saying you have to stick to that! In the two overshot patterns I’ve written for Gist, I used both Mallo and Beam as my pattern wefts.

In the Tidal Towels, a very simple overshot threading creates an undulating wave motif across the project. It’s easy and repetitive to thread, and since the overshot section is relatively short, it’s an easy way to get a feel for the technique.

The Bloom Table Squares are designed to introduce you to a slightly more complex threading—but in a short, easy-to-read motif. When I was a new weaver, one of the most challenging things was reading and keeping track of overshot threading and treadling—but I’ve tried to make it easy to practice through this narrow and quick project.

Overshot works best with a pattern weft that 2-4 times larger than your plain weave ground, but I haven’t always followed that rule, and I encourage you to sample and test your own wefts to see how they look! In the samples I wove for this article, I used 8/2 Un-Mercerized Cotton weaving yarn in Beige for my plain weave, and Duet in Rust, Mallo in Brick, and Beam in Blush for my pattern wefts.

The Bloom Table Squares are an excellent example of what weavers usually mean when they talk about traditional overshot or colonial overshot, but I prefer to use the term "floatwork" when talking about overshot. I learned this from the fantastic weaver and textile historian Deborah Livingston-Lowe of Upper Canada Weaving. Having researched the technique thoroughly for her MA thesis, Deborah found that the term "overshot" originated sometime in the 1930s and that historical records variably called these weaves "single coverlets’ or ‘shotover designs.’ Deborah settled on the term "floatwork" to speak about these textiles since it provides a more accurate description of what’s happening in the cloth, and it’s one that I’ve since adopted.

This book contains the collected drafts and work of Frances L. Goodrich, whose interest in coverlets was sparked when a neighbor gifted her one in the 1890s. Full of charming hand-painted drafts, this book offers a glimpse into North Carolina’s weaving traditions.

Amanda Ratajis an artist and weaver living and working in Hamilton, Ontario. She studied at the Ontario College of Art and Design University and has developed her contemporary craft practice through research-based projects, artist residencies, professional exhibitions, and lectures. Subscribe to herstudio newsletteror follow her onInstagramto learn about new weaving patterns, exhibitions, projects, and more.

As I began to plan the structure of the piece I knew that using an overshot technique for my weaving would probably give me the visual texture that I desired.

The overshot technique in weaving is accomplished by using two different thickness ofthread alternated in the weaving rows. The pattern row is made using the thicker of the two threads and usually skips over several threads to achieve the desired pattern that you are weaving. The thinner of the two threads is woven across the warp before and after each thicker pattern thread to “lock in” the pattern thread. The thinner threads are woven in tabby (weaving speak for plain weave).

I feel that using the overshot weaving technique helped me to capture the textual feeling I wanted for this runner. Here is how the project progressed and a list of the yarns that were used.

With the color pallet and types of yarn I chose and using the overshot technique, I felt like I was able to achieve the look that I wanted for this project. What do you think??

Half way through my weaving I decided I wanted to add a little something special to the piece that would bring the cultural influence in the tribal shield that inspired me to create this project to begin with. As I searched for that special something, I found a vendor on Etsy that imported fair trade beads from Africa. Handmade metal and hand-carved bone beads. I was pretty excited! Special handmade beads from another artist to compliment a handmade runner, just what the runner needed forthat finishing touch. When the beads arrived I laid them out on the runner that I was almost finished weaving and knew it was definitely the perfect accent!

Adding the beads to the finished runner was a long and tedious task but definitely worth the work, time and effort when I saw the finished project!! Once the beading was finished all that was left was to do the finishing wash and block drying and trimming off any overlapped threads in the weaving.

I actually had some beautiful brass and bone beads leftover from my weaving projects so I made those into some fun jewelry pieces . I’ll have some pictures of those in my next blog post.

Weaving rag rugs is an immensely satisfying process that enables you to use cast-off remnants of fabric - and a favorite old shirt or two - to make something beautiful and functional for your home. In this book, you"ll explore the fascinating history of rag weaving, learn how to weave a basic rag rug, master some of the most popular traditional designs, and experiment with contemporary techniques for weaving and embellishing rugs. Filled with scores of colour photographs of rugs by more than 40 artists from around the world, this book is a delight for weavers and non-weavers alike.

Weaving with rags developed out of genuine necessity centuries ago, when cloth was so highly treasured that it was often unwoven in order to reuse the thread. Although fabric is now commonly available at very low cost, weaving rag rugs remains an especially satisfying process. Transforming fabric remnants and old articles of clothing into beautiful, functional rugs yields a wonderful feeling of accomplishment, and it instills a sense of connection with history and tradition.

The basics of rag rug weaving have remained the same over the years, but the materials, designs, weave patterns, and color combinations have changed significantly. Today"s weavers have access to an abundant array of warp and weft materials, with a wide variety of fiber content, color, and pattern. There are few-if any-limitations on what you might incorporate into your design: plastic shopping bags, bread wrappers, nylon stockings, and industrial castoffs have all been included.

Once you feel comfortable with the basic techniques, you"ll want to sample the rag rug projects. There are a dozen in total, ranging in style from a subtle gradation of stripes to a vibrant tapestry inlay. You"ll find seaside motifs and square blocks, pale pastels and brilliant jewel tones. There is even a double weaving project chenille "caterpillars" are woven first, and these become the weft in a wonderfully textured chair pad. Each project is described in complete detail and accompanied by a weaving draft.

Throughout the book are full-color photographs of works by more than 40 artists from a dozen countries around the world. These images, together with how-to photography and detailed illustrations, will instruct you and inspire you to sample new directions in your weaving. A fascinating history of rag weaving complements this glorious collection of contemporary rugs.

One of the coolest things about weaving is that it is generally understood to have emerged at similar times in many different geographical locations around the world. People weave in different ways, for different purposes, and in different conditions. Learning from other weavers has been one of the most valuable experiences to my weaving practice. Since I expect most of us won"t be traveling much in the near future, I figured it was a good time to share some of my most meaningful travel experiences.

I"ve had the opportunity to go to to Mexico, India, Morocco, Europe, and many places in the US and Canada to learn from weaving experts. I’m going to share what I’ve learned along the way.

At first I was hesitant to take up the time of busy weavers. I felt like just another tourist distracting them from their work. Turns out, most of the weavers were really excited to meet a Canadian weaver! After a few interactions, I realized that it wasn"t all take, I had something to GIVE too. It can be tricky trying to communicate with a language barrier, but it isn"t impossible. In many situations in Morocco, I had no Arabic, and most of the weavers had little-no English, so we were both trying to communicate in French which was not great for either of us. The good thing about weaving is that so much of it can be communicated without any language at all. In the above image, I am learning a special weaving knot from Youseph that he learned as a child. After he taught me, I shared with him how I tie on the loom with a surgeons knot. I also helped him to lower his bench so it was more ergonomic. Even though Youseph is a lifelong weaver who drills holes in cards himself to make the patterns on his handmade Jacquard-like loom, I still had a little something to contribute.

Many weavers in North America are fortunate enough to have access to the weaving tools that they need. This isn"t always the case in many of the places I visited. Most of the looms I saw in India, and all of the looms I saw in Morocco were handmade, often by the weaver themselves. Popular scrap materials include toothpicks, bike parts, string, and sticks of all kinds.

I remember once for a project making about 30 string heddles because I had not planned well. I got very grumpy. My perspective is different now for sure. Have you ever been in a weaving situation where necessity was the mother of invention?

I was lucky enough to have a translator in the small town of Sefrou, where I had the opportunity to speak with Mustapha (see above image). He was excited to talk to another weaver and we shared weaving knowledge and stories. He told me that in Arabic, the warping mill is called the “heart,” because without a good warp, the weaving has no life. I think about that now when I use my mill. The translator told me that Mustapha was difficult to translate because he speaks in so many metaphors. Weaving is full of metaphors! How could he not?

Have you seen weaving at all in your travels? If money/time/coronavirus were no object, where would you go? Angela and I would love to hear about your weaving-travel adventures!

The Big Book of Weaving – Handweaving in the Swedish Tradition: Techniques, Patterns, Designs and Materials by Laila Lundell has been my reading selection for the past few weeks. There are books that you speed through and they give you great ideas. This is a book that is perfectly suited for winter months when you can take time to digest a section before moving on to the next.

This book has often been used as a textbook for new weavers wanting to know how to get started with their first floor loom. The project sequence starts from the very beginning using plain weave and moves through pattern weaving. The author presents both 4 and 8 shaft projects for each type of weaving.

Projects that I found quite interesting – “Kitchen Towels with Small Blocks” that can be woven with 16/2 cotton. In this project Ms. Lundell also offers a complete project plan for weaving the bands needed for hanging towels. A great mystery solved!

“Choosing the right materials for a weaving takes a lot of knowledge. It’s a good idea to train your eyes and fingertips to become familiar with various materials and to learn about their special qualities”

8613371530291

8613371530291