what is overshot weaving in stock

While it looks like it would be a very time-intensive and difficult technique to weave – it really isn’t! You just have to understand how and why it works the way it does. (We will get to that.)

This page may contain affiliate links. If you purchase something through these links then I will receive a small commission – at no extra cost to you! Please read our

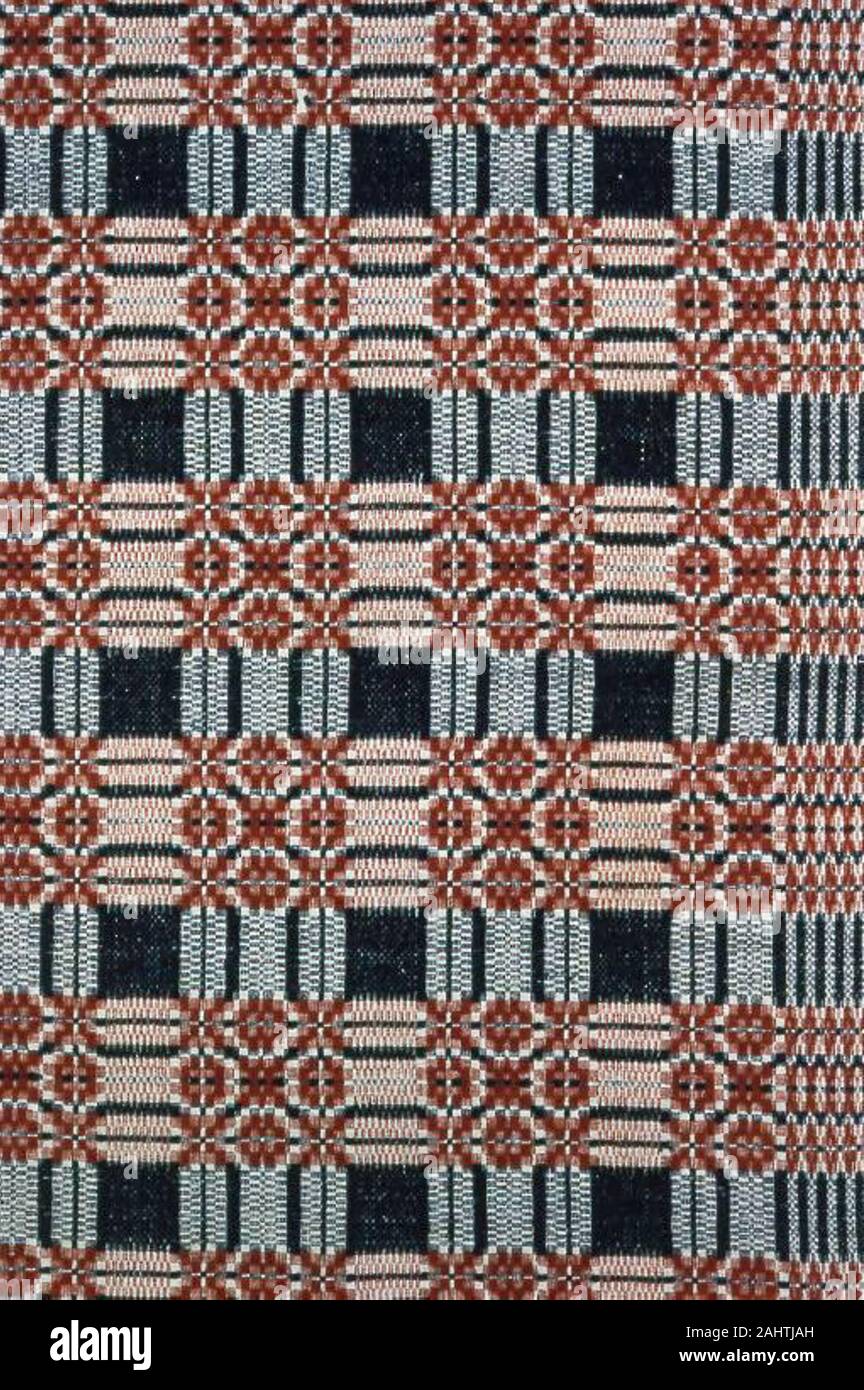

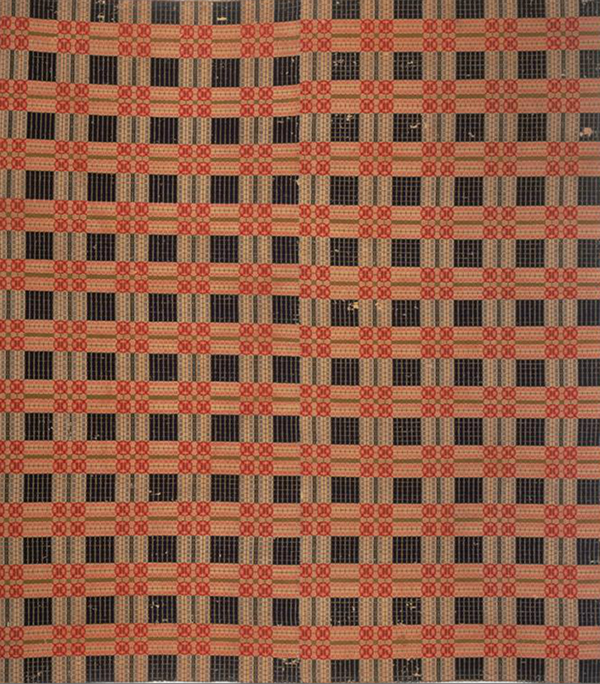

In its simplest form – overshot is a weaving technique that utilizes at least 2 different types of weft yarns and floats to create a pattern. These patterns are often heavily geometric.

Ground weft– plain weave pattern that is used between each row of your overshot pattern. This plain weave gives the textile structure and allows for large areas of overshot to be woven without creating an overly sleazy fabric. Without the use of a ground weft on an overshot pattern, the weaving would not hold together because there would not be enough warp and weft intersections to create a solid weaving.

They were most popular though in southern Appalachia and continued to be so even after textile technologies advanced. When other parts of colonial America moved to jacquard weaving, the weavers of southern Appalachia continued to weave their overshot coverlets by hand.

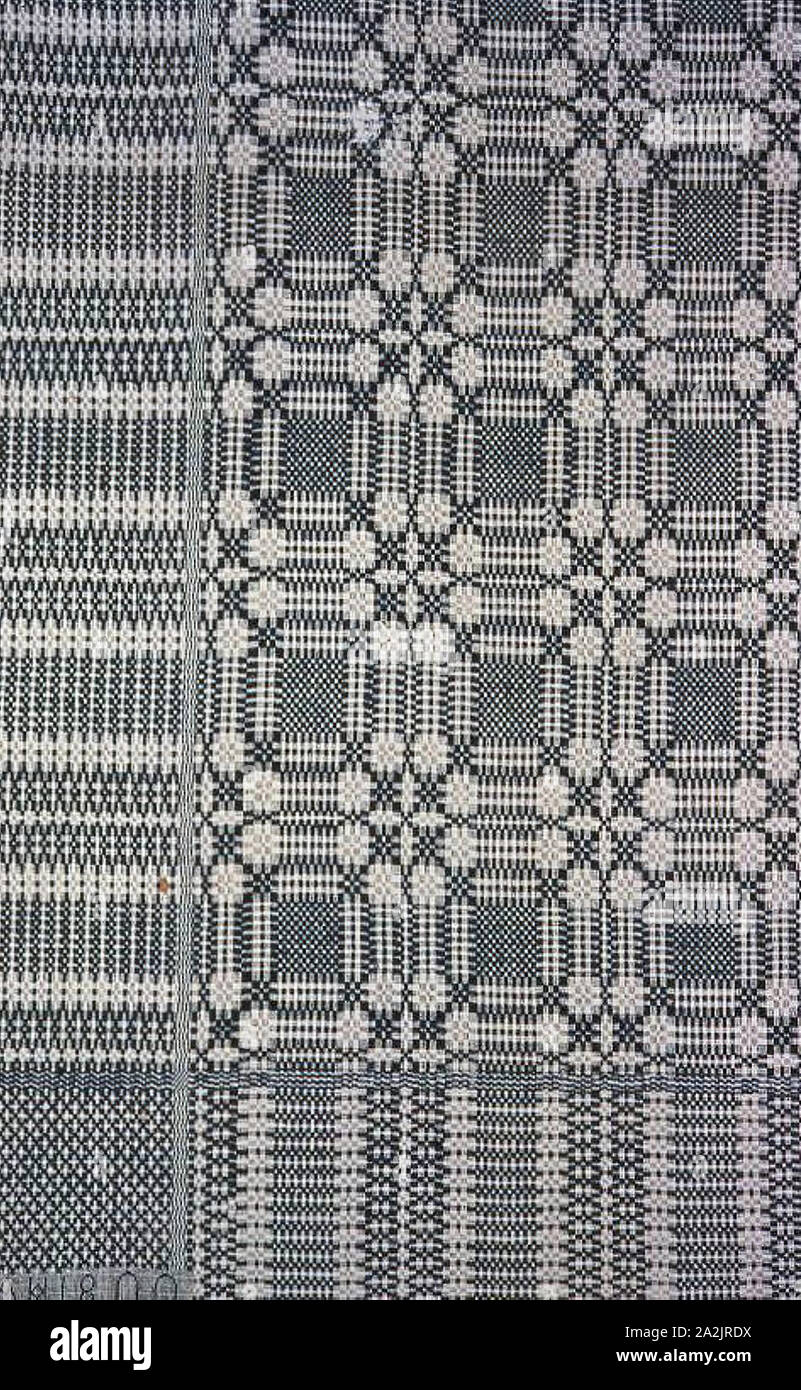

Since the overshot coverlets were most often woven at home on smaller looms they usually had a seam down the middle where two woven panels were sewn together.

The thing about overshot is that no matter the application, it is pretty impressive. Perhaps that is just my opinion, but due to how complex it can look, I feel that it is pretty safe to say.

Just because it was originally used for coverlets, does not mean it can only be used for coverlets. Changing aspects of the pattern like the colors used, or the way you use your ground weft can drastically change the look and feel of your weaving.

In the image below you can see the ground weft is not the same color throughout. Instead, I wove the ground weft as discontinuous so that I could add extra pattern and design into the weavings. In this case, you may be wondering how to deal with your weft yarns when they are in the middle of the weaving and not at the selvage.

The discontinuous weft yarns will float onto the back of the weaving until you are ready for them in their next pick. This does make your overshot weaving one sided since it will have vertical floats on the back. Keep this in mind if you want to try this technique out.

Also seen in the image above, the overshot yarn that I used was not all one color! This is a really simple way to get extra dimension and interest in your overshot if that is something you are looking for.

This makes it simple to be able to only weave overshot in certain parts of your weaving. If you want to do this then you can continue to weave your plain weave across the entire width of your weaving, but only weave overshot in specific areas. This creates a overshot section that functions similar to inlay.

Since the overshot pattern is strongly influenced by the weft yarns that are used it is important to choose the right yarns. Your weaving will be set up to the specification needed for a balanced plain weave. Make sure you understand EPI in order to get the right warp sett for your overshot weaving.

The ground weft used is almost always the same yarn as your warp. This allows the overshot weft to really be able to shine without contrasting warp and weft plain weave yarns.

In order to get the full effect of the overshot, it must be thick enough that when you are weaving your pattern it covers up the ground weft between each pass. If it is not thick enough to do this, it will still be overshot, but the full effect will not be seen.

What this warp thread does is serve as an all-purpose selvedge that does not correspond with your pattern. Instead, you would make sure to go around this warp thread every time to make sure that you are able to weave fully to the selvedge. Without this, your overshot weft will float awkwardly on the back of your weaving whenever the pattern does not take it to the edge.

I have mentioned this book multiple times because it really is such a great resource for any weaver looking to weave patterns of all types. It contains 23 pages of different overshot patterns (among so many other patterns) that you can set up on your floor or table loom.

Like a lot of different types of weaving, it is possible to do it on almost any type of loom that you have. The difference being that it might take you a little bit longer or require a bit more effort than if you did it on a traditional floor loom.

Weaving overshot on a frame loom or rigid heddle loom will require the use of string heddles and pick-up sticks that you have to manually use to create a shed.

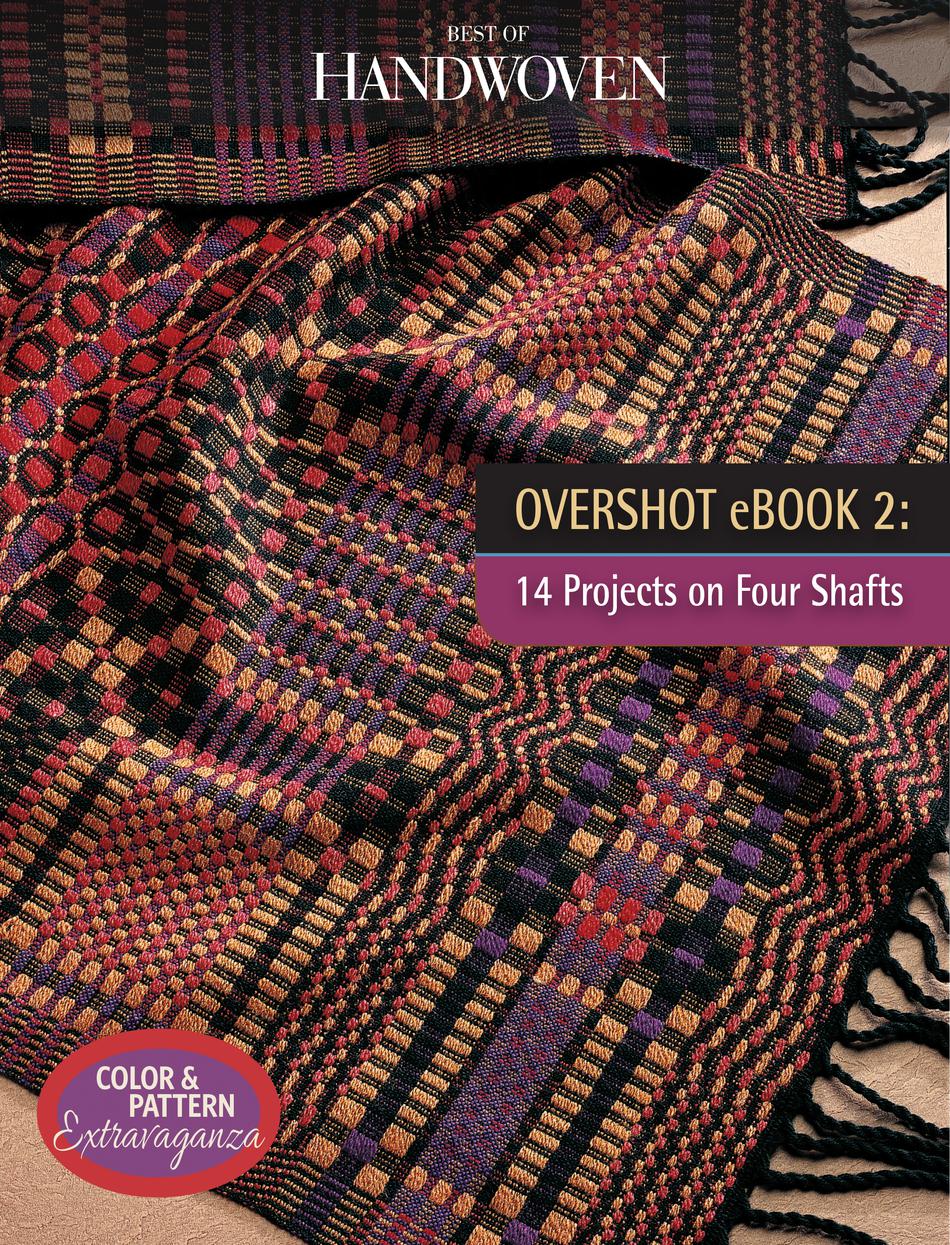

Overshot is a magical structure. The first time you weave it you can hardly believe the cloth that grows on your loom. Traditionally used to weave bed coverings, overshot has many beautiful applications in today"s world, from useful household textiles to breathtaking works of art. This versatile weave is subject to endless variations. Here are a few of our favorite tips and a few truly spectacular projects, too! If you are inspired, come visit us and learn from a master weaver, Joanne Hall. See details below about her workshop.

A slouchy bag by FiberMusings on Weavolution pairs leftover BFL singles with sturdy Cottolin to create a fashionable yet functional multi-colored bag. The draft is a design from Ann Weaver"s Handweavers Pattern Dictionary, and it"s a great way to integrate Overshot techniques while making an eye-catching accessory!

Another project that caught our eye recently was a shower curtain shared by GailR@30 shared on Weaving Today - it"s nothing short of amazing (click here to see for yourself)! Consisting of thirteen different overshot pattern threadings woven in thirteen different treadlings, 169 different design effects are created based on designs from Osma Gallinger Tod"s book The Joy of Handweaving. As Gail noted on her project page, a great way to make each design stand out is to separate them with twill bands (even though it might mean a little more work in the process!)

Or, you may choose to elevate your weaving like the work of art it most certainly is, as Evaweave did with her Overshot Study pieces. These two miniature silk rugs look lovely in a frame, don"t you think? The overshot pattern was adapted from Overshot Weaving by Ellen Lewis Saltzman, complementing one another perfectly.

Think overshot is too difficult to try? Deb Essen thinks otherwise! Fiber artist, designer, and teacher, Deb is a passionate weaver who specializes in using overshot name drafts to create "secret messages" in cloth.

On her website, she explains: "Overshot is a weave structure and a draft is the weaver"s guide to creating patterns in cloth. Overshot name drafts assign the letters of a name or phrase to the shafts on a loom, creating a pattern that is unique. The one-of-a-kind patterns become a secret hidden message in the cloth and only those knowing the secret can break the code."

Deb lets you in on the secret with her clever kits, each with a hidden message. We"re particularly fond of her That"s Doable kit, which features Mountain Colors hand-painted yarns and, as the name would imply, is our first choice for those new to overshot weaving.

Overshot weave is the topic this week. Even if you haven’t heard of overshot before, I’m guessing you will still recognize it. Have you ever seen a historical coverlet before? That is overshot. Typically 2 colors. ALL about the pattern. That’s the one! Overshot.

Overshot is a partnership between 2 shuttles. The first shuttle is all about the pattern. She flits all over the fabric making big leaps and seemingly impossible designs. The second shuttle is all plain weave. She’s the reliable one, making sure the fabric will actually hold together.

Overshot Weave – Overshot is a weaving pattern that was very common in Southern Appalachia. I found a great article with some history about overshot from Comfort Cloth Weaving. Here’s the link.

Duneland Weaver’s Guild – This is the local weaver’s guild that I belong to. The organization has been active for over 70 years and the members are crazy talented! It is a seriously gifted group of weavers. If you have a weaver’s guild near you, it is worth it to see what they are doing!

Weaving Draft – A weaving draft is like sheet music. It tells you how to set up the loom and then the order in which to toss the shuttles in order to recreate a specific pattern. Once you can read a draft, the weaving world is your oyster!

Great news – I have created a free .pdf that follows along with this weaving pattern series! It provides an overview of each weaving pattern. Tells you how to recognize it and what it is used for. Plus, I’ve included a few notes on how to create the pattern on your loom. It’s a fabulous resource! Click here to get your copy today. Happy Weaving!

This project was really popular when I posted it on Instagram, so I thought I would share it here also. It is a simple overshot pattern - with a twist. Also a great way to show off some special yarn. The yarn I used for my pattern was a skein of hand spun camel/silk blend. I wove the fabric on my Jack loom but you could also use your four or eight shaft loom.

Overshot is a weave structure where the weft threads jump over several warp threads at once, a supplementary weft creating patterns over a plain weave base. Overshot gained popularity in the turn of the 19th century (although its origins are a few hundred years earlier than that!). Coverlets (bed covers) were woven in Overshot with a cotton (or linen) plain weave base and a wool supplementary weft for the pattern. The plain weave base gave structure and durability and the woollen pattern thread gave warmth and colour/design. Designs were basic geometric designs that were handed down in families and as it was woven on a four shaft loom the Overshot patterns were accessible to many. In theory if you removed all the pattern threads form your Overshot you would have a structurally sound piece of plain weave fabric.

I was first drawn to Overshot many years ago when I saw what looked to me like "fragments" of Overshot in Sharon Aldermans "Mastering Weave Structures".

I have not included details of number of warp ends, sett and yarn requirements for my project - you can do your calculations based on the sett required for plain weave in the yarn you wish to use.

I wanted to use my handspun - but I only had a 100gms skein, I wanted to maximise the amount of fabric I could get using the 100gms. I thought about all the drafts I could use that would show off the weft and settled on overshot because this showcases the pattern yarn very nicely. I decided to weave it “fragmented” so I could make my handspun yarn go further. I chose a honeysuckle draft.

When doing the treadle tie-up I used 3 and 8 for my plain weave and started weaving from the left, treadle 3 - so you always know which treadle you are up to - shuttle on the left - treadle 3, shuttle on the right treadle 8. I then tied up the pattern on treadles 4,5,6 and 7. You can work in that order by repeating the sequence or you can mix it up and go from 4 to 7 and back to 4 again etc. You will easily see what the pattern is doing.

Lots of people think that overshot must be a complicated 8-shafts-and-above weave structure, but that is far from true. Most overshot designs can be woven on 4-shafts, and once you get into a weaving rhythm of pattern-tabby-pattern-tabby, weaving goes smoothly as the beautiful patterns emerge on your loom. That said, designing and weaving overshot requires a bit more concentration than plain weave.

Here are five tips from designer Pattie Graver, author of Next Steps in Weaving, to ensure great overshot results. The first three are probably ones you’ve already heard about weaving other structures, but the last two are about looking at overshot designs and color choices in a mindful way.

I follow the advice of Helene Bress in The Weaving Book: “Identify a diagonal line that appears in the cloth as you weave and try to keep that at 45 degrees.” I keep a protractor by my loom!

Consider putting on at least an extra yard of warp in order to get a feel for the draft. This will allow you to test for proper beat, colors, and other “what-ifs.” I often put on a 6-yard warp and use at least half of the warp for sampling.

You may wish to choose a different starting/stopping point than the one specified. As you study the drawdowns, you will discover that some drafts have small sections that can be woven separately from the overall design.

A small portion of the overall pattern makes a nice border on this Primrose Table Runner designed by Norma Smayda and woven by Ann Rudman, Handwoven November/December 2017. Photo by George Boe.

If warp and pattern weft are too close in value, the overshot designs will not appear in strong contrast. Remember, too, that the eye follows light, so bits of lighter pattern weft add interest to the cloth.

Debbi Rutherford used name drafting to create this overshot pattern and then used a variegated yarn for her pattern weft. Handwoven January/February 2017. Photo by Joe Coca.

Cloth is woven on a grid of vertical warps and horizontal wefts. But, with a bit of knowledge about designing weaving drafts, you can use these rectilinear elements to create smoothly flowing lines in your woven fabric.

In this article, I focus on designing with overshot blocks in order to create flowing curves large enough to be seen at a distance. I will also discuss "weaving as overshot" which is a method of applying overshot techniques to other weave structures and, finally, finish up with some strategies for designing curves in any weave structure.

Any weave structure with at least three blocks can produce diagonals. All you need is a diagonal progression in the threading with a corresponding diagonal progression in the tie-up and treadling. The simplest diagonal draft possible is a three-shaft twill.

In the twill draft above, the diagonal lines are only three threads apart, which might be too subtle an effect. To make the scale of your design larger, you can use a diagonal progression of weave-structure blocks instead of individual threads. The following draft shows an example of a diagonal progression using overshot blocks on four shafts.

Overshot is a weave structure creating a plain-weave cloth with decorative supplementary weft floats. These floats lie on top of (float over) the ground cloth. If you pull out all of the pattern weft threads, you are left with a plain weave cloth formed by the warp and the tabby weft. There are never any warp floats because of the tabby weft.

The tabby weft interlaces with the warp to form the plain weave background, so the tabby weft should be of similar value to blend visually with the warp. It does not have to be the same color as the warp. The tabby weft may the the same size as the warp, but I prefer to use a finer yarn for my tabby weft and a thicker yarn for my pattern weft.

As an example, if my warp is 8/2 cotton sett at 20 epi (recommended for plain weave) in white, my tabby weft will be 10/2 cotton, or perhaps 12/2. If my tabby weft is light blue, then the plain weave cloth will have a white warp and pale blue weft. I can change the color of the background by changing the color of the tabby weft.

The supplementary weft creates the pattern and is known as the pattern weft. Usually this is a thicker yarn than the tabby weft and it needs some contrast to show against the background. In the example above, an 8/2 or 6/2 or even a 5/2 cotton, or a similar size of wool, would be good for the pattern weft. In these drafts, the warp is light and the pattern weft is dark. Less contrast creates a more subtle effect.

Weaving software is very helpful for testing hues and values for weft yarns to use with your warp. If you choose to weave overshot with a single shuttle, choose a contrasting value to the warp for a subtle design but faster weaving.

If you put the curve in your threading, the waves travel across the fabric horizontally, in the direction of the weft. You can see this in the overshot draft below.

The benefit to having the curve in the threading is that the treadling then becomes a simple diagonal progression, which is especially useful if you are tromping the pattern, instead of using a dobby loom.

The downside is that handwoven textiles, such as scarves and shawls, tend to be longer than they are wide. Often a curve seems more natural when it flows up and down the fabric.

Another disadvantage to putting the curves in the threading is that it limits your ability to improvise curved designs organically at the loom. It"s easy to change treadling patterns during weaving. Changing the threading, however, is a much more involved process.

I learned how to make curves by studying a traditional overshot draft called Blooming Leaf (page 133 in A Handweaver"s Pattern Book by Marguerite Davison). In this draft, the treadling maintains a diagonal progression but the scale changes to make the shape "bloom" and undulate.

In order to make a curve, all you need to do is incrementally increase or decrease the number of times you repeat each pattern block in a diagonal progression.

To see how this works, use a diagonal threading sequence and start by treadling each block once, twice, then three and four times. You can see the diagonal line bend into a curve.

[Note: When I create overshot drafts, I place the first pattern block on treadle three; I like to weave the tabby picks with my left foot (alternating between treadles one and two) and use my right foot (on the remaining treadles) to weave the pattern weft and create the design.]

I start the curve by increasing the number of times a treadling block is repeated, going from the first pattern block to the last (and then wrapping around to the first block again to keep the line continuous). When the curve looks long enough, I reverse the order of the pattern blocks, going now from the last pattern block to the first.

Now that you know how to create curves, undulations, and reflected curves, you have the tools you need to create any kind of curve or diagonal line in four-shaft overshot. For a challenge, try making a long curve followed by a short curve, like a meandering river.

The methods described above also work for overshot on six, eight, ten, or more shafts. As you add additional shafts to your design, you gain the ability to create smoother and more dramatic curves.

Below is an example of an eight-shaft overshot threading; in this case a diagonal progression with a point and mirror symmetry. My treadling in this draft is an S-shaped curve. This is just one example of the many different curves you can weave on this threading.

Because the underlying structure of overshot is plain weave, any threading which can produce plain weave can theoretically be woven as overshot, alternating tabby and pattern weft.

The tabby weft blends visually with the warp, so that the pattern weft stands out. I generally use a tabby that is the same value (a measure of a color"s lightness or darkness) as the warp.

In the draft above, the threading on the right shows a four-shaft advancing twill. The threading on the left is a series of advancing points (a short sequence followed by a longer one).

The next draft shows an example of an advancing-point threading on eight shafts. This one begins 1-2-3-4-5-6-5-4-3. The next point starts at 2-3-4-5-6-7.

I wove the draft above using a 20/2 silk sett at 30 epi. I chose to sett the yarn this densely so I could weave both an overshot and twill version on the same warp. You can see the resulting cloth in the picture below.

How do I weave as overshot when my sett is more appropriate for twill? I use a tabby weft that is much finer than the warp, in this case 140/2 silk from Lunatic Fringe.

For example, the warp in the cloth below is hand-dyed in hot shades of red and orange. I chose a red tabby weft, so the background cloth would be very bright. For the pattern weft, I used a dark-purple yarn, with a deeper value than the background cloth. Because the pattern weft floats on top of the plain-weave ground cloth, it creates a textural, raised design element, which emphasizes the curved pattern.

Other times I choose to weave as overshot because the floats show off the pattern-weft yarn, such as the handspun wool used as the pattern weft in the cloth below.

It is easy and fun to make up a curved treadling at the loom, especially when weaving as overshot. Even after forty-two years of weaving, I still enjoy working with long, non-repeating treadlings; watching the curves grow and change as I weave. Instead of memorizing a sequence and repeating it carefully, I watch the design and think about where I want the next curve to go.

A side benefit of weaving long, undulating curves instead of small, repeated patterns is that a small variation in a repeat will stand out, but design variations are normal in organic curves.

The drape of overshot fabric is not as fluid as that of a twill fabric. So for a scarf or shawl I might choose a structure other than overshot. Fine silk, however, has such nice drape that I can weave as overshot and still get good results.

Generally this means repeating a treadling block. With a diagonal progression in the threading, you can treadle curves as long or short as you like. This applies to all weave structures.

With weaving software, it is easy to create curved overshot designs. Simply draw a freehand curve in the treadling—smoothing it out if necessary—and then add the tabby shots. Once you have the general idea from designing drafts, you can improvise new curved designs at the loom.

For other weave structures, creating a profile draft can be helpful. A profile draft is a design template that represents the woven design at one level of abstraction. To convert a profile draft into a weaving draft, you replace each block in a profile draft with the appropriate block of a given weave structure. You can, therefore, express a single profile draft in many different weave structures: overshot, summer-and-winter, Bronson lace, huck lace, double weave, etc.

Profile drafts with smooth, flowing curves are also useful for learning how to design graceful lines. Weaving software helps because you can quickly create and edit drafts. None of the weaving programs I"m familiar with have an option to create "graceful" or "smooth" curves. So you"ll have to train your hand and eye, but this comes with practice.

Another thing that can affect the smoothness of your curved designs is the number of blocks you have to work with. The more blocks you use in your design, the smoother your curves will look. A draft with only a few blocks is like a digital image with few pixels. It looks blocky.

The other factor affecting smoothness is the scale of the design. A miniature design can look smooth using only four or six blocks, but a larger-scale design—one using more (or larger) threads per repeat—needs more blocks or it will look pixelated. (Note: Sometimes the pixelated look is cool.)

I like smooth, flowing curves that are visible at a distance. So I look for structures that give me the maximum number of pattern blocks to design with. Generally I use weave structures where I have as many pattern blocks as there are shafts on my loom. On a four-shaft loom, I use crackle, overshot, advancing and network-drafted twills, advancing points, turned taqueté, rep, and shadow weave.

If you work with graph paper, remember to check the repeats, i.e., transitions, in the threading and treadling to make sure there aren"t gaps or discontinuous areas that affect the flow of your curve. In weaving software, you can do this easily by zooming out the view to check the draft over several repeats.

Design inspiration for curves is everywhere: winding rivers, sand dunes, landscapes, roads, and so on. In nature, there are more curves than straight lines!

(Editor"s Note: This article is part one of a two-part series. Look for Bonnie"s second installment, describing how to create curves using network-drafted twills, in August!)

The origin of the technique itself may have started in Persia and spread to other parts of the world, according to the author, Hans E. Wulff, of The Traditional Crafts of Persia. However, it is all relatively obscured by history. In The Key to Weavingby Mary E. Black, she mentioned that one weaver, who was unable to find a legitimate definition of the technique thought that the name “overshot” was a derivative of the idea that “the last thread of one pattern block overshoots the first thread of the next pattern block.” I personally think it is because the pattern weft overshoots the ground warp and weft webbing.

Overshot gained popularity and a place in history during the turn of the 19th century in North America for coverlets. Coverlets are woven bedcovers, often placed as the topmost covering on the bed. A quote that I feel strengthens the craftsmanship and labor that goes into weaving an overshot coverlet is from The National Museum of the American Coverlet:

Though, popular in many states during the early to mid 19th centuries, the extensive development of overshot weaving as a form of design and expression was fostered in rural southern Appalachia. It remained a staple of hand-weavers in the region until the early 20th century. In New England, around 1875, the invention of the Jacquard loom, the success of chemical dyes and the evolution of creating milled yarns, changed the look of coverlets entirely. The designs woven in New England textile mills were predominantly pictorial and curvilinear. So, while the weavers of New England set down their shuttles in favor of complex imagery in their textiles, the weavers of Southern Appalachia continued to weave for at least another hundred years using single strand, hand spun, irregular wool yarn that was dyed with vegetable matter, by choice.

And, due to the nature of design, overshot can be woven on simpler four harness looms. This was a means for many weavers to explore this technique who may not have the financial means to a more complicated loom. With this type of patterning a blanket could be woven in narrower strips and then hand sewn together to cover larger beds. This allowed weavers to create complex patterns that spanned the entirety of the bed.

What makes overshot so incredibly interesting that it was fundamentally a development of American weavers looking to express themselves. Many of the traditional patterns have mysterious names such as “Maltese Cross”, “Liley of the West”, “Blooming Leaf of Mexico” and “Lee’s Surrender”. Although the names are curious, the patterns that were developed from the variations of four simple blocks are incredibly intricate and luxurious.

This is only the tip of the iceberg with regard to the history of this woven structure. If you are interested in learning more about the culture and meaning of overshot, check out these resources!

The National Museum of the American Coverlet- a museum located in Bedford, Pennsylvania that has an extensive collection of traditional and jacquard overshot coverlets. Great information online and they have a “Coverlet College” which is a weekend series of lectures to learn everything about the American coverlet. Check out their website - coverletmuseum.org

Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women – This was an exhibit that traveled from Lowell, Massachusetts, Morehead, Kentucky, Knoxville, Tennessee, Raleigh, North Carolina, and ended at the Royal Museum in Edinburgh, Scotland. The exhibit contained a large number of overshot coverlets and the personal histories of those who wove them. I learned of this exhibit through an article written by Kathryn Liebowitz for the 2001, June/July edition of the magazine “Art New England”. The book that accompanied the exhibit, written by Kathleen Curtis Wilson, contains some of the rich history of these weavers and the cloth they created. I have not personally read the book, but it is now on the top of my wish list, so when I do, you will be the first to know about it! The book is called Textile Art of Southern Appalachia: The Quiet Work of Women and I look forward to reading it.

Overshot is an intricate weave structure in which pattern weft “shoots over” a grounded plain weave cloth to create a huge range of patterns. From undulating waves to dashing circles, the weaver can create complex patterns on only 4 shafts. This weave structure has been used all over the world, but developed most widely in Appalachian coverlets and table linens during early colonial America. In this class, students will learn more about this beloved weave structure and weave their own overshot table runners, placemats, or samples using cotton and wool on 4 shaft floor looms. Explore blending colors, manipulating patterns, and practicing weaving this two shuttle weave structure. No weaving experience is necessary, but some experience is helpful.

Crazyshot - creative overshot weaving - introduces anyone who uses a rigid heddle loom to a whole world of creative weaving. Using just one heddle and one pick-up stick, you’ll explore color, design, and texture, taking your weaving to the next level.

Complete step-by-step instructions are included for weaving all 14 of the designs in this book. Also provided are how-tos for the single heddle overshot technique, reading charts for the rigid heddle loom, and finishing techniques, along with lots of tips and tricks for successful and

Complex patterning is easier than it looks with this simple charted technique. All you need are basic rigid heddle warping and weaving skills to start your next weaving adventure!

One of the great things about having been a blogger for 12 years (did I actually just admit that?!) is that you occasionally get to look back and see how very far you’ve come.

Over three years ago, when my David Louet floor loom was still somewhat new to me, I wrotethis post on overshot. If you read it, you will discover that my initial relationship with overshot was not a very positive one.

Back then, I was a little harder on myself as a learning weaver. By now, I’ve realised that weaving, just like life, is a journey that has a beginning but no end. Back then, I thought that my ultimate goal was to be a “master weaver”.

Honestly, I don’t even really know what that means but it no longer matters to me. I just want to be the best weaver I can be, but even more importantly, to continue to be fulfilled, challenged and rewarded by doing it.

The happy ending to the initial overshot sob story is that I can weave overshot now. Quite well, in fact! And I also teach it. And I happen to love it, very, very much. Don’t you love a happy ending?

I don’t think there was any particular moment where I thought to myself “I can weave overshot now!” I didn’t even weave any overshot for quite some time after that initial attempt. But slowly it tempted me back, and we started over. It was just a matter of sticking with it, employing some specific techniques and practice, practice, practice until it feels like an old friend.

My love of overshot has only increased with my more recent discovery of American Coverlets. I loved the look of the coverlets and the history behind them before I realised that so many of them were woven in the wonderfully humble 4 shaft overshot.

I’ve put a lot of research time into coverlets this year and have made it a big weaving goal of mine to weave my first coverlet, which is quite an undertaking, but I relish the thought.

Now that I have quite a lot of experience weaving overshot, I want to share my best overshot tips with you in hope that you too will fall in love with this wonderful weave structure.

I know, I know, sampling takes time and yarn, it’s true. But it teaches you so, so much. It can also be more economical, as you can test your yarns out for suitability before committing to a larger project. Trust me, sampling is so well worth the time!

To weave overshot you need a warp yarn, a tabby yarn and a pattern weft yarn. Using the same yarn for warp and tabby works perfectly. For the pattern weft, I like to use a yarn that is twice the size of the tabby/warp yarn. I have experimented with using doubled strands of tabby/warp yarn in a contrasting colour, but it just doesn’t look as good. A thicker pattern yarn is the way to go.

What will the size of your item be? A miniature overshot pattern may get lost in a blanket, but may be perfect for a scarf. As a general rule, a good way to estimate the size of one repeat of your pattern just by looking at the draft is to see how many repeats are in one threading repeat. Also consider the thickness of your yarns and the sett you intend to weave.

Just to give you an idea, my current project is woven at 20 ends per inch with 8/2 cotton for warp and tabby and fingering weight wool for the pattern weft. The weaving draft has 50 threads in one threading repeat. My design repeats on the loom are around 2.5″ wide and just under 5″ long, which is a great size for the 30″ x 99″ throw I’m weaving.

This is a non negotiable for overshot if you want neat edges and less headaches! You get used to using floating selvedges very quickly, so don’t stress if you have no experience with them.

This is another selvedges tip. I’ve experimented with crossing the two weft yarns at the selvedge to see whether it gives a neater edge, but it doesn’t, at least for me. So, instead of twisting the two wefts at each selvedge when throwing a new pick, I just let them follow one another sequentially and my edges are much neater that way.

Besides the thickness of the pattern weft yarn, you will also want to consider what kind of bloom it may have after wet finishing. For example, I know that my fingering weight wool blooms beautifully, whereas a cotton of the same size would not bloom in the same way. I very much like the contrast of the 8/2 cotton background with the plump wool pattern weft.

I’m going to sound like a broken record, but once again, a sample will show you everything you need to know about how your yarn will behave as a finished piece.

I’m often surprised by the potential of yarns to leach dye in the wet finish process. I’ve had certain yarns that I’ve used frequently that will leach dye sometimes and not others.

This is a particular problem if your colours and white on red or navy on white – you want to preserve that white and not have it come out of the wash as a pink or light blue!

The best way to avoid this is through vigilance, especially in the first 10-15 minutes of your woven piece making contact with water. If you see dye beginning to run, take it out of the warm wash and rinse in cold water until the water runs clear. Place back in the warm water and maintain your watch on it. Repeat the rinsing process if needed.

There are 6 treadles needed for overshot, even though you weave on 4 shafts. The two extra treadles are for the tabby weave. I always set up my pattern treadles in the centre of the loom – two on the left and two on the right. Then I set up a “left” tabby and a “right” tabby treadle. To do this on my 8 shaft loom I leave a gap between the pattern treadles and the tabby treadles so that my feet can “see” and differentiate between a pattern and tabby treadle.

I like to advance little and often. You will find your own preference or “sweet spot” for weaving, but I find that with overshot I advance a lot more frequently at a much smaller amount than I do usually.

The firmness of beat will depend on a few things. Your chosen yarns, the weave structure, the width of the project and the tension your warp is under are all important considerations. I let the project dictate.

An example of this is that I wove an overshot sampler right before Is started my main project (the throw). It was a narrow warp (around 8″) and a different overshot threading and treadling than I’m using for the project.

But for my throw project, I am beating harder and sometimes having to beat twice. Because of the width of the project, I need to be careful that I’m beating evenly, and that is easier to do if I’m beating more firmly.

I personally do not use a temple. Some weavers will say they won’t weave without one. I’ve tried using a temple on many of my projects, particularly if I’m getting broken edge warp threads (signs of tension problems and too much draw in). But I will avoid using one wherever I can get away with it, and I don’t use one for weaving overshot.

I find that if I’m careful with weft tension and warping evenly, I do not get excessive draw in. It is something I’m constantly aware of while weaving and remind myself of tip 4 so that my weft picks are not pulling in at the edges.

Overshot on the loom today. I’ve admired the “Mariner’s Pride” motif in Josephine Estes’ monograph, “Original Miniature Patterns for Hand Weaving,” which is in the public domain, for some time. This is my spin on it. So far. Still getting my head around it. #overshot #handweaving #fourshaftweaving #leagueofnhcraftsmen #weaving

Overshot: The earliest coverlets were woven using an overshot weave. There is a ground cloth of plain weave linen or cotton with a supplementary pattern weft, usually of dyed wool, added to create a geometric pattern based on simple combinations of blocks. The weaver creates the pattern by raising and lowering the pattern weft with treadles to create vibrant, reversible geometric patterns. Overshot coverlets could be woven domestically by men or women on simple four-shaft looms, and the craft persists to this day.

Summer-and-Winter: This structure is a type of overshot with strict rules about supplementary pattern weft float distances. The weft yarns float over no more than two warp yarns. This creates a denser fabric with a tighter weave. Summer-and-Winter is so named because one side of the coverlet features more wool than the other, thus giving the coverlet a summer side and a winter side. This structure may be an American invention. Its origins are somewhat mysterious, but it seems to have evolved out of a British weaving tradition.

Twill:Twill along with plain and satin weave is one of the three simple weave structures. Twill is created by repetition of a regular ratio of warp and weft floats, usually 1:2, 1:3, or 2:4. Twill weave is identifiable by the diagonal orientation of the weave structure. This diagonal can be reversed and combined to create herringbone and diamond effects in the weave.

Double Cloth: Usually associated with professional weavers, double cloth is formed from two plain weave fabrics that swap places with one another, interlocking the textile and creating the pattern. Coverlet weavers initially used German, geometric, block-weaving patterns to create decorative coverlets and ingrain carpeting. These coverlets contain twice the yarn and are twice as heavy as other coverlets.

Beiderwand: Weavers in Northern Germany and Southern Denmark first used this structure in the seventeenth century to weave bed curtains and textiles for clothing. Beiderwand is an integrated structure, and the design alternates sections of warp-faced and weft-faced plain weave. Beiderwand coverlets can be either true Beiderwand or the more common tied-Beiderwand. This structure is identifiable by the ribbed appearance of the textile created by the addition of a supplementary binding warp.

Figured and Fancy: Although not a structure in its own right, Figured and Fancy coverlets can be identified by the appearance of curvilinear designs and woven inscriptions. Weavers could use a variety of technologies and structures to create them including, the cylinder loom, Jacquard mechanism, or weft-loop patterning. Figured and Fancy coverlets were the preferred style throughout much of the nineteenth century. Their manufacture was an important economic and industrial engine in rural America.

Multi-harness/Star and Diamond: This group of coverlets is characterized not by the structure but by the intricacy of patterning. Usually executed in overshot, Beiderwand, or geometric double cloth, these coverlets were made almost all made in Eastern Pennsylvania by professional weavers on looms with between twelve and twenty-six shafts.

America’s earliest coverlets were woven in New England, usually in overshot patterns and by women working collectively to produce textiles for their own homes and for sale locally. Laurel Thatcher Ulrich’s book, Age of Homespun examines this pre-Revolutionary economy in which women shared labor, raw materials, and textile equipment to supplement family incomes. As the nineteenth century approached and textile mills emerged first in New England, new groups of European immigrant weavers would arrive in New England before moving westward to cheaper available land and spread industrialization to America’s rural interior.

The coverlets from New York and New Jersey are among the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlets. NMAH possesses the earliest Figured and Fancy coverlet (dated 1817), made on Long Island by an unknown weaver. These coverlets are associated primarily with Scottish and Scots-Irish immigrant weavers who were recruited from Britain to provide a skilled workforce for America’s earliest woolen textile mills, and then established their own businesses. New York and New Jersey coverlets are primarily blue and white, double cloth and feature refined Neoclassical and Victorian motifs. Long Island and the Finger Lakes region of New York as well as Bergen County, New Jersey were major centers of coverlet production.

German immigrant weavers influenced the coverlets of Pennsylvania, Virginia (including West Virginia) and Maryland. Tied-Beiderwand was the structure preferred by most weavers. Horizontal color-banding, German folk motifs like the Distelfinken (thistle finch), and eight-point star and sunbursts are common. Pennsylvania and Mid-Atlantic coverlets tend to favor the inscribed cornerblock complete with weaver’s name, location, date, and customer. There were many regionalized woolen mills and factories throughout Pennsylvania. Most successful of these were Philip Schum and Sons in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and Chatham’s Run Factory, owned by John Rich and better known today as Woolrich Woolen Mills.

Coverlet weavers were among some of the earliest European settler in the Northwest Territories. After helping to clear the land and establish agriculture, these weavers focused their attentions on establishing mills and weaving operations with local supplies, for local markets. This economic pattern helped introduce the American interior to an industrial economy. It also allowed the weaver to free himself and his family from traditional, less-favorable urban factory life. New land in Ohio and Indiana enticed weavers from the New York and Mid-Atlantic traditions to settle in the Northwest Territories. As a result, coverlets from this region hybridized, blending the fondness for color found in Pennsylvania coverlets with the refinement of design and Scottish influence of the New York coverlets.

Southern coverlets almost always tended to be woven in overshot patterns. Traditional hand-weaving also survived longest in the South. Southern Appalachian women were still weaving overshot coverlets at the turn of the twentieth century. These women and their coverlets helped in inspire a wave of Settlement Schools and mail-order cottage industries throughout the Southern Appalachian region, inspiring and contributing to Colonial Revival design and the Handicraft Revival. Before the Civil War, enslaved labor was often used in the production of Southern coverlets, both to grow and process the raw materials, and to transform those materials into a finished product.

Because so many coverlets have been passed down as family heirlooms, retaining documentation on their maker or users, they provide a visual catalog of America’s path toward and response to industrialization. Coverlet weavers have sometimes been categorized as artisan weavers fighting to keep a traditional craft alive. New research, however, is showing that many of these weavers were on the forefront of industry in rural America. Many coverlet weavers began their American odyssey as immigrants, recruited from European textile factories—along with their families—to help establish industrial mills in America. Families saved their money, bought cheaper land in America’s rural interior and took their mechanical skills and ideas about industrial organization into the American heartland. Once there, these weavers found options. They could operate as weaver-farmers, own a small workshop, partner with a local carding mill, or open their own small, regional factories. They were quick to embrace new weaving technologies, including power looms, and frequently advertised in local newspapers. Coverlet weavers created small pockets of residentiary industry that relied on a steady flow of European-trained immigrants. These small factories remained successful until after the Civil War when the railroads made mass-produced, industrial goods more readily available nationwide.

Weave structures often have specific threading and treadling patterns that are unique to that particular weave structure and not shared with others. This book takes you out of the traditional method of weaving overshot patterns by using different treadling techniques. This will include weaving overshot patterns such as Summer/Winter, Italian manner, starburst, crackle, and petit point just to name a few. The basic image is maintained in each example but the design takes on a whole new look!

Each chapter walks you through the setup for each method and includes projects with complete drafts and instructions so it’s easy to start weaving and watch the magic happen! Try the patterns for scarves, table runners, shawls, pillows, and even some upholstered pieces. Once you"ve tried a few projects, you"ll be able to apply what you"ve learned to any piece you desire!

Author of the popular Overshot Simply and Shadow Weave Simply now shares her explorations of overshot weaving structures. Her teaching style is to break down the weave structure into its basic parts so that it is easy to understand, and then teach you how the parts work together to create the weave structure so that you can use any pattern or create your own.

In the video, I mention learning how to weave Krokbragd. If you are interested in learning about this weaving technique, I encourage you to check out our course at the School of SweetGeorgia, Weaving Krokbragd, taught by Debby Greenlaw.

The overshot weaving project shown is woven on a 16″ Ashford Table Loom 8 shaft, The yarns used are Ashford 100% mercerised cotton in 10/2 and 5/2. (We don’t have this yarn currently listed on our site, but we’re able to order it in for you. Send us an email at: info@sweetgeorgiayarns.com!) The pattern is Overshot Sampler from the book Next Steps in Weaving by Pattie Graver

Congratulations to Katrina at Crafty Jaks as she just hit publish on the Crafty Jaks – The Inquisitive Crafter YouTube channel! If you love spinning, dyeing and wool, please go check it out and subscribe.

A feature of the new shopping cart are improvements for the home page and the ability to show more images in the ads. I have decided to make use of a single cart to keep things simple, this shopping cart will allow me to carry both handwoven, and downloadable products at the same time. I also like to print and do illustration work, and likely you will begin to see a greater diversity in my product line. Hopefully, you will see something that catches your eye and think; Here is a way to support this artist.

I am beginning my 30th year of handweaving, and find I am not a true “hard core” academic (I may not have that laser focus). I love to teach and love working with people in general. I excel at small groups and one on one, solving problems as we weave together. I love to research and curate information about weaving especially in the 1700s to early 1900s. I want to be part of the solution to identify and keep handweaving history and technical information in the accessible in public domain as much as possible. But, at the same time software is not free, and web servers cost money to run. Keeping something alive will require a business model that generates supportable income in to the future after I am gone. I know that I do not have the physical strength/endurance or the time to be a production weaver, I am a designer at heart. I love to solve problems, and then I move on to the next problem.

With COVID-19 I lost my opportunity to demonstrate handweaving to the public by letting the new weavers try the looms for themselves, and have retreated into my studio. While being in the studio, I decided that I could once again concentrate on historic research and drafting of contemporary versions of old patterns. I discovered that many of the designs I had created earlier in my career were no longer accessible because of the software going out of production, or becoming so expensive you needed to be a production weaver to be able to afford it. I have been dedicating my free time to capturing what data I could from these drafts and I will be transferring them into a more usable format for future generations to enjoy. As I complete the task I will post them to the website. I can not list them for free, because I need to cover sample production and web hosting hosting costs.

I have both 8 shaft looms, a computer-dobby 24 shaft loom, and a very large drawloom. I design for all three types of looms. In the shop I have decided to mark the number of shafts needed for a draft at the top of the description so as not to disappoint a weaver. You will know what you purchasing before you hit the download button. I also also elected to include weaving software files and manual draft files in the same draft archive packages so that people no longer have to choose one or the other.

A few more words about the work I believe I can deliver to the public. I like to design drafts and weave it before I post it to ensure accuracy, but at this point some days I do more designing than weaving. I think I would like to work out a system with a fellow weaver(s), I would like to see I if can afford to pay a weaver to weave samples of these designs that I can post on the website and give credit for the work that was done. I have no worries if you determine that you would like to weave the design for production and sell items. I am aware that drafts can not be copyrighted, and so will not chase you down if you use a my design for sale in your shop. As I have mentioned before, it is not my intent to be a production weaver. If a weaver were interested in this type of arrangement, I would ask that you email me directly with what your financial requirements might be for making samples and what type of loom (mostly number of shafts) you are using for sampling. Sample sizes should be 10″ x 10″ or larger if the draft requires it for a full repeat. I am interested in high contrast samples so that it is clear to the weaver what is happening between the warp and weft threads.

For weavers downloading designs, please understand you are supporting my ability to create and maintain self sustaining a database of information related to weaving for access by yourself and other weavers. Downloading once and sharing widely with others defeats the business case for website sustainability. The drafts will have less value, and we all lose the resources we need to keep historic weaving documents and drafts available to the public. I also believe that I do not want to require a subscription to access the draft data or the learning that I have gathered. So this website will always have a public front end that is useful and full featured that is free.

I do not feel that I am in competition with sites like some international pattern libraries or handweaving.net. Historicweaving.com as a website predates them. I am not intending to scan books, or digitize a drafts in that way. I want to use the historic drafts to study how and why they were made, what makes them look the way they do, and how they can be modified to make new designs that reflect our time and current tastes. Understand my statement above that I am not a pure academic, who is driven to study the past and document it a completely as possible. I want to see the past, and bring it to back to life in an approachable way for today’s weavers and looms. My site will be different than others as I am different weaver. I have had this dream for a long time, and have spent that time learning about weaving and weaving software. I like to use Facebook as my studio blog, because Facebook can moderate comments faster and more safely. I want this expanded website for its database potential, and the ability to generate revenue to keep it self sustaining. I use Pinterest as a visual catalogue of ideas (a designer’s morgue file) to explore in the future. I’m learning how to write and present full digital content, some video, some pictorial, some e-books and stories. I believe we all learn in different ways and I want to explore ways to help other weaver’s pass on their notes/journals/drafts to the future as well. I have taken a few months to reflect on what I really want to do and how I want to spend my time. I want to research and to weave. (Ideally, I would like to travel as well, but that will take time and a vaccine.)

If I offer an handwoven item in my shop for sale it is most likely to be a one of kind – if it is not, the size of the edition will be stated. I have no desire to weave long warps of the same pattern. It slows me down once I have solved the design problem, I like to move on to the next. I like efficiency, but I am far more likely to want to achieve accuracy, especially in complex structures. I have been known to weave, unweave and rethread multiple times until I get the loom to match the draft. I spend more time finding ways to warp and weave better. I am known to innovate. If someone asks me how long it took to weave this particular item, it is hard to answer directly because I have to determine if should I tell you about all of the samples I made before I achieved success. (Again, note, I am not a production weaver). What will make my hand woven gifts special is you can be certain that you will not find another one just like it anywhere. When I use my looms I use them as close to their full capability as possible. My personal patterns are complex on purpose, I have a special hand loom, a 100 shaft combination drawloom and I like to show what it can do. To purchase a handwoven piece from me, pricing includes the cost of overhead for maintaining full weaver’s studio, time spent learning about weaving, the cost of materials and fact the item is unique. Your purchase dollars support my research efforts directly. I reinvest my profit dollars into the website and new weaving history research opportunities.

I began with creating an Illustrated Weaving Glossary meant for beginning weavers – https://historicweaving.com/wordpress/product/illustrated-weaving-glossary/ – never get confused about when a word is used and what it is referring to.

I have been researching extensively for the past couple of yearsMary Meigs Atwater’s Shuttle Craft Guild – Lessons and her American Handweaving Book. Many of the documents I am working from are now in the public domain because their initial publication was 100 years ago, and are even more significant because they are her attempts to record information that was sent to her from other hand weavers throughout the United States. These items are truly meant to be preserved for the public because they came from the public. Since their initial publication, draft notation standards for these structures and patterns have changed significantly, usually it requires a bit of detailed reading to learn how to read the drafts from the manuscript.

I have taken the time to record some of the larger coverlet radiating overshot pattern drafts in profile draft form making them more accessible to weavers who use drafting software. From the profile you can try different structures, colors and layouts to find a design that is pleasing to you. I have built instructions that show you how the draft is composed and how it can be modified. I would like to think of it as giving you design components more than a formal project plan. If you want the formal project plan approach use the Woven as Drawn in instructions. My goal in my presentation is to increase your understanding so that you can design your own projects and not not to restrict you to copying standardized patterns.

I added an eBook/PDF and draft package for Radiating Overshot Patterns – Sunrise, Blooming Leaf, Bow Knot and the Double Bow Knot. These designs include full drafts, profile drafts and woven as drawn-in drafts. This is the link to purchase the draft archive and the instruction ebook: https://historicweaving.com/wordpress/product/radiating-patterns-for-historic-overshot/

The Radiating Patterns ebook shows you how the drafts are related, the Draft Archive catalog details all of the profiles for easy reference to file names, and there are more than 68 drafts in the package. Included are the Lee’s Surrender, Sunrise and Blooming Leaf coverlets drafts. These drafts are the Series IV groups a,b,c and d – radiating patterns. From Mary Atwater’s original work combined with any examples I could find in digital museum collections that had no accompanying drafts with them.

Another bonus item from the American Handweaving Book, when published Mary Atwater made use of black and white photographs of historic coverlets she located in musuems. I have tracked the coverlets down and found color digital images from the current holding Museum’s digital collections. Use this link to download a copy of the original book manuscript and the link overlay to view the color images. https://historicweaving.com/wordpress/product/the-shuttle-craft-book-of-american-handweaving-updated-photo-links-in-pdf-format/

From the Mary Meigs Atwater’s Shuttle Craft Guild – Lessons, lesson 2 which concerns the Honeysuckle draft, I completed a copy of the Sampler Project that she requested as part of the lesson. That lesson encouraged me to create more than 50 unique treadlings to create the sampler assignment from Lesson 2, I named “Mournin’ Max” to honor the 100th anneversary of death of her husband Maxwell Atwater in 1919, an event that marked the beginning of her full time career in weaving that lasted for the rest of her life. Click on this link for the draft Archive. https://historicweaving.com/wordpress/product/draft-package-for-mournin-max-project/

Completion of the documentation of the reticule from the Montana Historical Society Museum. Can be woven on a 4 shaft loom. The structure is Honeysuckle Twill.

A contemporary version of the Lee’s Surrender draft, using a unit tie weave that can be woven on 6 shafts. In this archive there are colored versions of Lee’s Surrender as found in museum collections.

Also I am doing work documenting the drafts for the early Jacquard coverlet designs and determining what designs and motifs can be woven on conventional looms. Those that can not I will be using my drawloom to complete a sample of the designs for posterity.

This post may help explain how my needle pillow cloth was woven. These pieces were made on the same warp. I had made a dozen or so pillow fronts and backs (in plain weave or tabby). Then I got creative and played with ideas of what else could be woven on the same warp. This is a scroll I made. I used the fabric I wove on the needle pillow warp for the background. It measures 7 ¾” x 26” including fringe.

I wove some samples and decided to make this for my scroll. The warp was handspun singles from Bouton. I wanted to see if I could use this fragile cotton for a warp. I used a sizing for the first time in my weaving life. The pattern weft is silk and shows up nicely against the matt cotton.

Here is a piece with two samples. The I used silk chenille that I’ve been hording dyed with black walnuts. In one part I used the chenille as the pattern weft. It looks similar to the needle pillows except I used only 1 block. The tabby was black sewing thread, I believe. For the flat sample, I used the reverse: the chenille for the tabby weft and the sewing thread for the pattern weft. Again I only used one of the blocks.

For this sample I used all sewing thread (easier with only one shuttle.) Again I used only one block and the pattern and tabby wefts were sewing thread. I do love to try things.

This illustration and quote are in The Weaving Book by Helen Bress and is the only place I’ve seen this addressed. “Inadvertently, the

8613371530291

8613371530291