dc power tong casing lawsuit in stock

The case was certified as a collective action under the FLSA. While collective actions share characteristics with class actions, they are not the same. In fact, in an FLSA case, an employee must opt-in, meaning that he must affirmatively sign a document stating they wish to be part of a lawsuit. In contrast, the law presumes employees in class action actions to have joined the lawsuit, unless the opt-out. best sex sites in Behchokǫ̀ online dating hookup fwb dating in West Linton officer dating enlisted punishment for adultery hp 7520 fax hook up a girl pesters me about dating her swinger community lesbian speed dating bristol uk local sex in El Molino dating apps for asians who want to meet asians

The Plaintiffs in the DC Power Tong Lawsuit sent notice and consent forms to the potential collective members on January 18, 2017. A copy of the November 21, 2016 Order granting conditional certification can be found here.

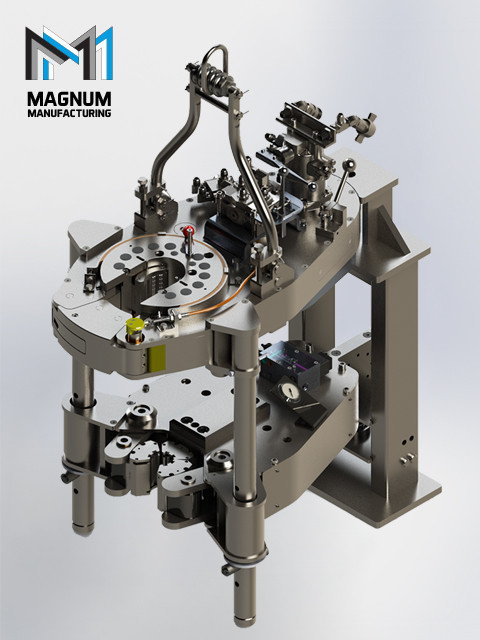

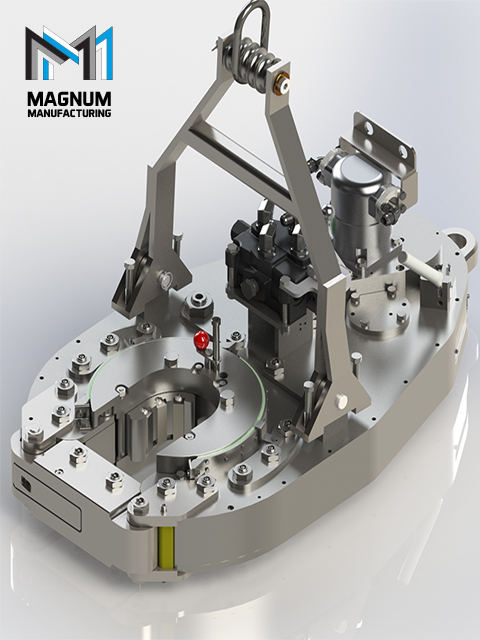

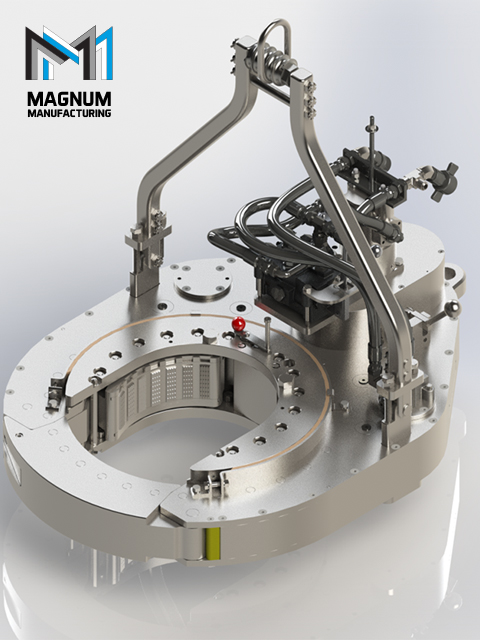

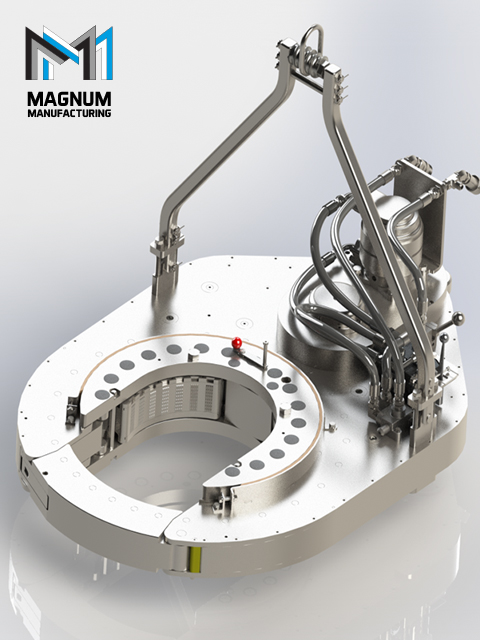

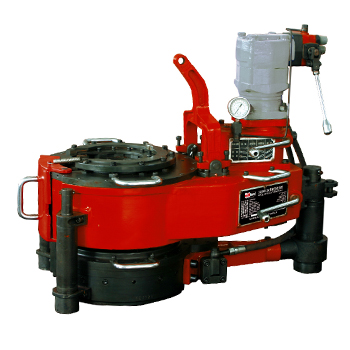

DC Power Tong continues to set the standard in the casing and tubing service industry by offering superior service & innovative casing technology. To exceed our customersʼ expectations, DC Power Tong also provides hydro test trucks, pressure test units, and equipment and pipe wrangler rentals to ensure your project is completed safely and efficiently. At DC Power Tong, we treat your project as if it is our very own, and thatʼs what weʼre all about.

SEC v. Gianluca Di Nardo, Corralero Holdings, Inc., Oscar Ronzoni, Paolo Busardo, Tatus Corp., and A-Round Investment SA (originally filed as SEC v. One or More Purchasers of Call Options for the Common Stock of DRS Technologies, Inc. and American Power Conversion Corp.)

“My dad gave me the phone,” Tong recalls. “The guy said, ‘This is whoever whoever from Fordham, and we’re from public safety. And we’re on your street right now.’”

It was late on the night of June 4. Earlier that day, Tong — a rising Fordham senior studying business, who immigrated to America from China when he was 6 — had been reflecting on how grateful he was to live in a free society. On that same date in 1989, Chinese troops drove tanks into a pro-democracy demonstration led predominantly by outspoken college students like Tong, in what would come to be known internationally as the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

“Tiananmen is an important discussion every year when the time comes,” Tong said. “My family moved here to America because of the opportunities and freedoms it provides. My parents want me to have a bright future here.”

So on June 4, Tong posted to Instagram a memorial for those killed at Tiananmen Square. The photo seemed to contrast the tragedy with the realization of his own American dream: A sunny backyard on a summer day, a freshly-mowed lawn, a BBQ grill — and Tong with a half-smile holding a Smith & Wesson rifle.

But well before Fordham security officers showed up at his door that night, the Austin Tong story was already on a crash course with major news headlines.

Before the summer was over, Tong would find himself fighting in court to defend his freedom of speech, serving as the catalyst for a formal investigation into Fordham’s practices by the United States government, and becoming the unlikely poster boy — gun and all — for the rights of American college students everywhere.

Tong’s Tiananmen Square Instagram post drew support, but also immediate criticism from some students who saw it. Many of them had also seen a post Tong made the previous day, when he uploaded a picture of retired St. Louis police captain David Dorn.

Dorn, who was black, was killed in St. Louis by looters after protests over the death of George Floyd turned violent. Tong objected to what he charactarized as society’s “nonchalant” attitude over Dorn’s murder. Tong said he felt Dorn’s life — and violent death — were not getting the attention they deserved.

The social media backlash was swift, and Fordham says it immediately received complaints about Tong’s posts. Specifically, some suggested Tong’s reference to Tiananmen Square could instead have been a threatening response to those who criticized his post about David Dorn.

The security officers that visited Tong’s home at Fordham’s behest quickly concluded as much, determining Tong had purchased his firearm legally and did not pose a threat to campus. Then they left.

Within days, Fordham opened a formal investigation into Tong’s Instagram posts, and held a June 10 hearing. More than a month later, on July 14, Fordham notified Tong he had been found guilty of violating university policies on “bias and/or hate crimes” and “threats/intimidation.” Tong’s probation banned him from physically visiting campus without prior approval and from taking leadership roles in student organizations. (Tong had previously been active in student government as a vice president and student senator.) He was also required to write an apology letter and complete implicit bias training.

Failure to comply with any of Fordham’s terms, Tong’s sanction letter stated, would result in “immediate suspension or expulsion from the university.”

“When Tong immigrated to the United States from China at six years old, his family sought to ensure that he would be protected by the rights guaranteed by their new home, including the freedom of speech and the right to bear arms,” wrote FIRE Program Officer Lindsie Rank. “Here, however, Fordham has acted more like the Chinese government than an American university, placing severe sanctions on a student solely because of off-campus political speech.”

“At the time, what was I supposed to do?” Tong said. “I’m a rising senior and I didn’t want to jeopardize my possibilities in the future, and so I complied.”

(Just a few months earlier a New York court found that Keith Eldredge, the dean who punished Tong, had violated Fordham students’ expressive rights in a separate case.)

Because he’s fighting the charges in court, Tong may just be able to complete his senior year. As an interim measure while Tong’s lawsuit progresses, Fordham has allowed him back on campus — provided he notifies the school in advance, reports to the security office first, and has an officer follow him everywhere he goes.

The suit has taken on an additional dimension, with the intervention of the U.S. government on Tong’s behalf. In a first, the Department of Education formally announced in last month that it was concerned Fordham had broken its promises of free expression in the Tong case — which could expose the university to liability of up to $58,328 per violation.

“I’m just like any other boy. I play sports sometimes. I play video games. I think I’m a good person. I think I’m a friendly person,” Tong said. “But I’d have to say I’m a strong person, too, because I do like to say my views.”

“If you back down, people will take advantage of that. And that’s what happened to me,” Tong said. “You back down, your life’s ruined. Whether it’s physically, materially, or spiritually.”

Tong doesn’t believe anyone involved, whether Fordham or the critical students on social media, ever really feared that he might commit violence because he chose to take a photo with a gun.

Despite the “mean” messages — and even threats of violence — that he received on his Instagram posts, Tong said he got a lot of support, including a substantial amount from students who messaged him privately, for fear of retribution for championing him publicly.

As a Chinese immigrant whose family fled a repressive government — a country where college students like him have been murdered by the government for simply expressing their views — Tong worries that American students fighting against free expression don’t understand the gravity of what they’re doing.

Every time a student asks a university to investigate or punish a peer for simply expressing a controversial viewpoint, Tong argues, everyone’s right to free expression erodes a little more.

“Most countries in the world don’t have privileges that Americans have, which is the right to speak without any legal consequence,” Tong said. “They don’t understand that.”

So Tong says he will fight for the rights of his fellow students to speak out, even if a growing subset of them don’t seem to understand why doing so is important.

He hopes even students who disagree with his views, might be persuaded to support his right to express them. After all, Tong’s freedom to speak his mind on social media is the same as the right of his most virulent critic to do the same.

Fordham’s policies guarantee such freedoms for all students. At least in theory. Tong said he is committed to helping make those promises a reality. Other students, he adds, can help.

“I will say, for young people, the best thing you can do to hold these institutions accountable is to speak up about it,” Tong said. “And if they really did something wrong, sue them.”

October 2022 — New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin filed a lawsuit against ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, ConocoPhillips, and the American Petroleum Institute for the damage that their climate deception is causing to communities across the state.

September, 2020 — Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings filed a lawsuit against 31 fossil fuel companies “to hold them accountable for decades of deception about the role their products play in causing climate change, the harm that is causing in Delaware, and for the mounting costs of surviving those harms.”

September 2020 — The City of Charleston is suing 24 fossil fuel companies to hold them accountable for lying about climate change harms they knowingly caused — and to make them pay a fair share of the damage. Charleston’s was the first such lawsuit filed in the American South.

September 2020 — Hoboken, the coastal “Mile Square City,” is the first municipality to file a climate liability lawsuit in New Jersey. The city’s lawsuit argues that ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips and the American Petroleum Institute’s climate deception violates the state’s consumer fraud statute and provides grounds for common law claims of public and private nuisance, trespass and negligence.

October 2022 — New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin filed a lawsuit against ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, ConocoPhillips, and the American Petroleum Institute for the damage that their climate deception is causing to communities across the state.

September, 2020 — Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings filed a lawsuit against 31 fossil fuel companies “to hold them accountable for decades of deception about the role their products play in causing climate change, the harm that is causing in Delaware, and for the mounting costs of surviving those harms.”

September 2020 — The City of Charleston is suing 24 fossil fuel companies to hold them accountable for lying about climate change harms they knowingly caused — and to make them pay a fair share of the damage. Charleston’s was the first such lawsuit filed in the American South.

September 2020 — Hoboken, the coastal “Mile Square City,” is the first municipality to file a climate liability lawsuit in New Jersey. The city’s lawsuit argues that ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips and the American Petroleum Institute’s climate deception violates the state’s consumer fraud statute and provides grounds for common law claims of public and private nuisance, trespass and negligence.

Through lawsuits filed around the country, or by simply wielding the threat of legal action, these loosely affiliated groups have targeted individual counties and states and, in some cases, set broader legal precedent.

In Wisconsin, a conservative legal center won a case before the state Supreme Court stripping local health departments of the power to close schools to stem the spread of disease.

In California, a lawsuit brought by religious groups challenging a health order that limited the size of both secular and nonsecular in-home gatherings as covid-19 surged made it to the U.S. Supreme Court. There, the conservative majority, bolstered by three staunchly conservative justices appointed by President Donald Trump, issued an emergency injunction finding the order violated the freedom to worship.

Other cases have chipped away at the power of federal and state authorities to mandate covid vaccines for certain categories of employees or a governor’s ability to declare emergencies.

Republican attorneys general, meanwhile, have found in covid-related mandates an issue that resonates viscerally with many red-state voters. Louisiana Attorney General Jeff Landry joined a suit against New Orleans over mask mandates, taking credit when the mandate was lifted. Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody sued the Biden administration over strict limits on cruise ships issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, arguing the CDC had no authority to issue such an order, and claimed victory after the federal government let the order expire.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton joined with the Texas Public Policy Foundation to sue the CDC over its air travel mask mandate. The case was put on hold after a Florida federal district judge in April invalidated the federal government’s transportation mask mandates in a case brought by the Health Freedom Defense Fund, a group focused on “bodily autonomy.” The Biden administration is fighting that ruling.

Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt has sued and sent cease and desist letters to dozens of school districts over mask mandates, and set up a tips email address where parents could report schools that imposed such mandates. The majority of his suits have been dismissed, but Schmitt has claimed victory, telling KHN “almost all of those school districts dropped their mask mandates.” This year, legislators from his own political party grew so tired of Schmitt’s lawsuits that they stripped $500,000 from his budget.

“Our efforts have been focused solely on preserving individual liberties and clawing power away from health bureaucrats and placing back into the hands of individuals the power to make their own choices,” Schmitt, who is running for U.S. Senate, said in a written response to KHN questions. “I’m simply doing the job I was elected to do on behalf of all six million Missourians.”

Public health is largely a local and state endeavor. And even before the pandemic, many health departments had lost staff amid decades of underfunding. Faced with draining pandemic workloads and legislation from conservative forces aimed at stripping agencies’ powers, health officials often find it difficult to know how they can legally respond to public health threats.

“You destroy government, and you destroy our emergency response powers and police powers — good luck. There will be no one to protect you.”Connecticut Attorney General William Tong (D-Conn.)

The legal threats have fundamentally changed the calculus for what powers to use when, said Brian Castrucci, president and CEO of the de Beaumont Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to improving community health. “Choosing not to use a policy today may mean you can use it a year from now. But if you test the courts now, then you may lose an authority you can’t get back,” he said.

By no means have the blocs won all their challenges. The Supreme Court recently declined to hear a Becket lawsuit on behalf of employees challenging a vaccine mandate for health care workers in New York state that provides no exemption for religious beliefs. For now, the legal principles that for nearly 120 years have allowed governments to require vaccinations in schools and other settings with only limited exemptions remain intact.

Connecticut Attorney General William Tong, a Democrat, decried the wave of litigation in what he called a “right-wing laboratory.” He said he has not lost a single case where he was tasked with defending public health powers, which he believes are entirely legal and necessary to keep people alive. “You destroy government, and you destroy our emergency response powers and police powers — good luck. There will be no one to protect you.”

As public health powers fade from the headlines, the groups seeking to limit government authority have strengthened bonds and gained momentum to tackle other topics, said Paul Nolette, chair of the political science department at Marquette University. “Those connections will just keep thickening over time,” he said.

Connecticut and Delaware have joined a growing list of states, cities and counties that have filed climate change lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry, claiming oil and gas companies knew their products caused sea level rise and stronger hurricanes and willfully misled the public about those and other dangers related to global warming.

Connecticut’s lawsuit, filed Monday, named ExxonMobil as a sole defendant, while the lawsuit filed on Friday by Delaware named 31 fossil fuel companies and trade groups. They joinedMassachusetts, Rhode Island and Minnesota as states that have filed such litigation.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, who served 36 years as a senator from Delaware, cited the state’s lawsuit in aclimate change address on Monday to underscore the costs of global warming and the Trump Administration’s failure to address the issue. He called Trump, who was surveying the devastation of wildfires in California, a “climate arsonist.”

The coastal city of Charleston, South Carolina, also filed a climate lawsuit last week, joining close to 20 other cities and counties seeking to hold the fossil fuel industries liable for damages resulting from increased flooding and precipitation, droughts and intensifying storm surges, in addition to sea level rise and stronger hurricanes. The other cities include Baltimore, Oakland, San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

In Connecticut’s suit filed Monday, Attorney General William Tong sued Exxon for violating the state’s Unfair Trade Practices Act, which allows for wide-ranging claims of public and private nuisance, trespass, negligence and for violating its Consumer Fraud Act.

“ExxonMobil sold oil and gas, but it also sold lies about climate science,” Tong said when announcing the multi-billion dollar climate lawsuit against the company.

This spate of lawsuits comes after a series of recent rulings in similar cases that appear to give the advantage to states, counties and cities, legal scholars say.

The lawsuits also may send further tremors through the financial world that this summer has seenExxon dropped from the Dow Jones Industrial Average and a U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission report that concluded climate change threatens U.S. financial markets, those experts say.

Unlike the other climate lawsuits confronting the oil and gas industry that sweep up the world’s largest producers, the Connecticut lawsuit singles out Exxon as the sole defendant because the company’s deceptive record is well established, Tong said in an email interview.

“ExxonMobil is a leader in the industry and has been for decades,” Tong said. “We have evidence that shows that Exxon knew from its own scientists that climate change was occurring, made a deliberate decision to deceive consumers, and then successfully implemented that plan over the course of decades.

The climate lawsuits citean InsideClimate News series and a later Los Angeles Times story that revealed the extent of Exxon’s knowledge about the central role of fossil fuels in causing climate change as far back as the 1970s, based on research performed by its own scientists.

“ExxonMobil’s campaign of deception has contributed to myriad negative consequences in Connecticut, including but not limited to sea level rise, flooding, drought, increases in extreme temperatures and severe storms, decreases in air quality, contamination of drinking water, increases in spread of disease, and severe economic consequences,” Connecticut’slawsuit says.

The lawsuit seeks money to pay for defending against climate change threats, restitution for remediation costs already made, disgorgement of corporate profits, civil penalties and disclosure of all climate research.

Although the industry will no doubt put up a strenuous fight against these lawsuits, its chances of winning them have been diminished by a series of court rulings favorable to the plaintiffs, said Richard Frank, director of the California Environmental Law & Policy Center at the University of California, Davis School of Law.

Thefirst salvo in the legal war was fired in 2017 when Marin and San Mateo counties, near San Francisco, and the city of Imperial Beach, south of San Diego, filed climate lawsuits and drew national attention for daring to take on the powerful fossil fuel industry.

A ripple from the mounting number of lawsuits could be the further weakening of the oil industry’s standing in financial markets, said Pat Parenteau, a professor of environmental law at the Vermont Law School.

While the states, cities and counties, for the most part, want their lawsuits heard in state courts, the industry prefers the federal courts as a venue so that they can arguethe Clean Air Act and other federal laws preempt any claim under state law that carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels cause climate change and related property damage.

Delaware’s lawsuit against 31 fossil fuel entities and trade groups claims negligent failure to warn, trespass, public nuisance and multiple violations of Delaware’s Consumer Fraud Act. It seeks monetary damages to compensate the state and punish the companies, including $10,000 per violation of the Consumer Fraud Act.

“Defendants have known for decades that climate change impacts could be catastrophic, and that only a narrow window existed to take action before the consequences would be irreversible,” Democrat Kathy Jennings, the Delaware attorney general, says in the lawsuit

At the heart ofthe lawsuit is the matter of who will pay for the mounting financial, environmental and public health costs of the climate crisis, Jennings said during a news conference announcing the lawsuit.

The lawsuit further blasts the industry for falsely claiming through advertising campaigns … that their businesses are substantially invested in lower carbon technologies and renewable energy sources.

“In truth, each Fossil Fuel Defendant has invested minimally in renewable energy while continuing to expand its fossil fuel production … None of Fossil Fuel Defendants’ fossil fuel products are ‘green’ or ‘clean’ because they all continue to ultimately warm the planet,” according to the lawsuit.

“These special-interest-promoted lawsuits designed to punish a few companies who lawfully deliver affordable, reliable and ever cleaner energy undermine real efforts to address the complex policy issues presented by global climate change,” Chevron spokesperson Sean Comey said in an email. “There is no evidence Chevron misled the public about climate change. Those claims are false.”

The Charleston lawsuit seeks to hold two dozen major oil and pipeline companies accountable for climate change damages to the city. The lawsuit claims their products and the spread of misinformation about fossil fuels have caused increasing and disastrous flooding.

“As a direct and proximate consequence of Defendants wrongful conduct described in this complaint, the environment in and around Charleston is changing, with devastating adverse impacts on the City and its residents,” according tothe lawsuit, which asserts six causes of action, including public and private nuisance, strict liability and negligent failure to warn, trespass and violations of South Carolina’s Unfair Trade Practices Act

The City has incurred significant costs on capital projects to address sea level rise, including rebuilding its aging Low Battery Seawall, installing check valves to prevent tidal intrusion on the City’s storm drain system and redesigning and retrofitting its floodwater drainage system to keep up with increased flooding caused by sea level rise, including by constructing more than 8,000 feet of new drainage tunnels, according to the lawsuit.

Says Charleston’s lawsuit: “The City seeks to ensure that the parties who have profited from externalizing the consequences and costs of dealing with global warming and its physical, environmental, social, and economic consequences, bear the costs of those impacts on Charleston, rather than the City, taxpayers, residents, or broader segments of the public.”

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Robert Drain must approve the deal, which protects the Sacklers from civil lawsuits. Purdue requested a March 9 hearing for Drain to review the agreement.

Opioid overdose deaths soared to a record during the COVID-19 pandemic, including from the powerful synthetic painkiller fentanyl, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said.

Purdue filed for bankruptcy in 2019 in the face of thousands of lawsuits accusing it and members of the Sackler family of fueling the opioid epidemic through deceptive marketing of its highly addictive pain medicine.

Tong and the mediator urged Drain to allow victims of the opioid epidemic to address the court when the judge considers approving the settlement and to order the Sackler family members to attend.

The space around a pipe in a well bore, the outer wall of which may be the wall of either the bore hole or the casing; sometimes termed the annular space.†

One or more valves installed at the wellhead to prevent the escape of pressure either in the annular space between the casing and the drill pipe or in open hole (for example, hole with no drill pipe) during drilling or completion operations. See annular blowout preventer and ram blowout preventer.†

A heavy, flanged steel fitting connected to the first string of casing. It provides a housing for slips and packing assemblies, allows suspension of intermediate and production strings of casing, and supplies the means for the annulus to be sealed off. Also called a spool.†

A wire rope hoisting line, reeved on sheaves of the crown block and traveling block (in effect a block and tackle). Its primary purpose is to hoist or lower drill pipe or casing from or into a well. Also, a wire rope used to support the drilling tools.†

On diesel electric rigs, powerful diesel engines drive large electric generators. The generators produce electricity that flows through cables to electric switches and control equipment enclosed in a control cabinet or panel. Electricity is fed to electric motors via the panel.†

A diesel, Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG), natural gas, or gasoline engine, along with a mechanical transmission and generator for producing power for the drilling rig. Newer rigs use electric generators to power electric motors on the other parts of the rig.†

A blowout preventer that uses rams to seal off pressure on a hole that is with or without pipe. It is also called a ram preventer. Ram-type preventers have interchangeable ram blocks to accommodate different O.D. drill pipe, casing, or tubing.†

A hole in the rig floor 30 to 35 feet deep, lined with casing that projects above the floor. The kelly is placed in the rathole when hoisting operations are in progress.†

Wedge-shaped pieces of metal with teeth or other gripping elements that are used to prevent pipe from slipping down into the hole or to hold pipe in place. Rotary slips fit around the drill pipe and wedge against the master bushing to support the pipe. Power slips are pneumatically or hydraulically actuated devices that allow the crew to dispense with the manual handling of slips when making a connection. Packers and other down hole equipment are secured in position by slips that engage the pipe by action directed at the surface.†

A relatively short length of chain attached to the tong pull chain on the manual tongs used to make up drill pipe. The spinning chain is attached to the pull chain so that a crew member can wrap the spinning chain several times around the tool joint box of a joint of drill pipe suspended in the rotary table. After crew members stab the pin of another tool joint into the box end, one of them then grasps the end of the spinning chain and with a rapid upward motion of the wrist "throws the spinning chain"-that is, causes it to unwrap from the box and coil upward onto the body of the joint stabbed into the box. The driller then actuates the makeup cathead to pull the chain off of the pipe body, which causes the pipe to spin and thus the pin threads to spin into the box.†

The large wrenches used for turning when making up or breaking out drill pipe, casing, tubing, or other pipe; variously called casing tongs, rotary tongs, and so forth according to the specific use. Power tongs are pneumatically or hydraulically operated tools that spin the pipe up and, in some instances, apply the final makeup torque.†

The space around a pipe in a well bore, the outer wall of which may be the wall of either the bore hole or the casing; sometimes termed the annular space.†

One or more valves installed at the wellhead to prevent the escape of pressure either in the annular space between the casing and the drill pipe or in open hole (for example, hole with no drill pipe) during drilling or completion operations. See annular blowout preventer and ram blowout preventer.†

A blowout preventer that uses rams to seal off pressure on a hole that is with or without pipe. It is also called a ram preventer. Ram-type preventers have interchangeable ram blocks to accommodate different O.D. drill pipe, casing, or tubing.†

A heavy, flanged steel fitting connected to the first string of casing. It provides a housing for slips and packing assemblies, allows suspension of intermediate and production strings of casing, and supplies the means for the annulus to be sealed off. Also called a spool.†

A wire rope hoisting line, reeved on sheaves of the crown block and traveling block (in effect a block and tackle). Its primary purpose is to hoist or lower drill pipe or casing from or into a well. Also, a wire rope used to support the drilling tools.†

On diesel electric rigs, powerful diesel engines drive large electric generators. The generators produce electricity that flows through cables to electric switches and control equipment enclosed in a control cabinet or panel. Electricity is fed to electric motors via the panel.†

A diesel, Liquefied Petroleum Gas (LPG), natural gas, or gasoline engine, along with a mechanical transmission and generator for producing power for the drilling rig. Newer rigs use electric generators to power electric motors on the other parts of the rig.†

A hole in the rig floor 30 to 35 feet deep, lined with casing that projects above the floor. The kelly is placed in the rathole when hoisting operations are in progress.†

Wedge-shaped pieces of metal with teeth or other gripping elements that are used to prevent pipe from slipping down into the hole or to hold pipe in place. Rotary slips fit around the drill pipe and wedge against the master bushing to support the pipe. Power slips are pneumatically or hydraulically actuated devices that allow the crew to dispense with the manual handling of slips when making a connection. Packers and other down hole equipment are secured in position by slips that engage the pipe by action directed at the surface.†

A relatively short length of chain attached to the tong pull chain on the manual tongs used to make up drill pipe. The spinning chain is attached to the pull chain so that a crew member can wrap the spinning chain several times around the tool joint box of a joint of drill pipe suspended in the rotary table. After crew members stab the pin of another tool joint into the box end, one of them then grasps the end of the spinning chain and with a rapid upward motion of the wrist "throws the spinning chain"-that is, causes it to unwrap from the box and coil upward onto the body of the joint stabbed into the box. The driller then actuates the makeup cathead to pull the chain off of the pipe body, which causes the pipe to spin and thus the pin threads to spin into the box.†

The large wrenches used for turning when making up or breaking out drill pipe, casing, tubing, or other pipe; variously called casing tongs, rotary tongs, and so forth according to the specific use. Power tongs are pneumatically or hydraulically operated tools that spin the pipe up and, in some instances, apply the final makeup torque.†

8613371530291

8613371530291