dc power tong casing lawsuit made in china

The case was certified as a collective action under the FLSA. While collective actions share characteristics with class actions, they are not the same. In fact, in an FLSA case, an employee must opt-in, meaning that he must affirmatively sign a document stating they wish to be part of a lawsuit. In contrast, the law presumes employees in class action actions to have joined the lawsuit, unless the opt-out. Bellavista mature cougar hookers anal sex on the second date sexuall dating São Sebastião do Passé adult dating websites in Gapan best real cougar dating site reddit am i dating or hooking up laptop cougar dating La Concepción shemale casual sex local sex hookups Grandyle Village

The Plaintiffs in the DC Power Tong Lawsuit sent notice and consent forms to the potential collective members on January 18, 2017. A copy of the November 21, 2016 Order granting conditional certification can be found here.

“My dad gave me the phone,” Tong recalls. “The guy said, ‘This is whoever whoever from Fordham, and we’re from public safety. And we’re on your street right now.’”

It was late on the night of June 4. Earlier that day, Tong — a rising Fordham senior studying business, who immigrated to America from China when he was 6 — had been reflecting on how grateful he was to live in a free society. On that same date in 1989, Chinese troops drove tanks into a pro-democracy demonstration led predominantly by outspoken college students like Tong, in what would come to be known internationally as the Tiananmen Square Massacre.

“Tiananmen is an important discussion every year when the time comes,” Tong said. “My family moved here to America because of the opportunities and freedoms it provides. My parents want me to have a bright future here.”

So on June 4, Tong posted to Instagram a memorial for those killed at Tiananmen Square. The photo seemed to contrast the tragedy with the realization of his own American dream: A sunny backyard on a summer day, a freshly-mowed lawn, a BBQ grill — and Tong with a half-smile holding a Smith & Wesson rifle.

But well before Fordham security officers showed up at his door that night, the Austin Tong story was already on a crash course with major news headlines.

Before the summer was over, Tong would find himself fighting in court to defend his freedom of speech, serving as the catalyst for a formal investigation into Fordham’s practices by the United States government, and becoming the unlikely poster boy — gun and all — for the rights of American college students everywhere.

Tong’s Tiananmen Square Instagram post drew support, but also immediate criticism from some students who saw it. Many of them had also seen a post Tong made the previous day, when he uploaded a picture of retired St. Louis police captain David Dorn.

Dorn, who was black, was killed in St. Louis by looters after protests over the death of George Floyd turned violent. Tong objected to what he charactarized as society’s “nonchalant” attitude over Dorn’s murder. Tong said he felt Dorn’s life — and violent death — were not getting the attention they deserved.

The social media backlash was swift, and Fordham says it immediately received complaints about Tong’s posts. Specifically, some suggested Tong’s reference to Tiananmen Square could instead have been a threatening response to those who criticized his post about David Dorn.

The security officers that visited Tong’s home at Fordham’s behest quickly concluded as much, determining Tong had purchased his firearm legally and did not pose a threat to campus. Then they left.

Within days, Fordham opened a formal investigation into Tong’s Instagram posts, and held a June 10 hearing. More than a month later, on July 14, Fordham notified Tong he had been found guilty of violating university policies on “bias and/or hate crimes” and “threats/intimidation.” Tong’s probation banned him from physically visiting campus without prior approval and from taking leadership roles in student organizations. (Tong had previously been active in student government as a vice president and student senator.) He was also required to write an apology letter and complete implicit bias training.

Failure to comply with any of Fordham’s terms, Tong’s sanction letter stated, would result in “immediate suspension or expulsion from the university.”

“When Tong immigrated to the United States from China at six years old, his family sought to ensure that he would be protected by the rights guaranteed by their new home, including the freedom of speech and the right to bear arms,” wrote FIRE Program Officer Lindsie Rank. “Here, however, Fordham has acted more like the Chinese government than an American university, placing severe sanctions on a student solely because of off-campus political speech.”

“At the time, what was I supposed to do?” Tong said. “I’m a rising senior and I didn’t want to jeopardize my possibilities in the future, and so I complied.”

(Just a few months earlier a New York court found that Keith Eldredge, the dean who punished Tong, had violated Fordham students’ expressive rights in a separate case.)

Because he’s fighting the charges in court, Tong may just be able to complete his senior year. As an interim measure while Tong’s lawsuit progresses, Fordham has allowed him back on campus — provided he notifies the school in advance, reports to the security office first, and has an officer follow him everywhere he goes.

The suit has taken on an additional dimension, with the intervention of the U.S. government on Tong’s behalf. In a first, the Department of Education formally announced in last month that it was concerned Fordham had broken its promises of free expression in the Tong case — which could expose the university to liability of up to $58,328 per violation.

“I’m just like any other boy. I play sports sometimes. I play video games. I think I’m a good person. I think I’m a friendly person,” Tong said. “But I’d have to say I’m a strong person, too, because I do like to say my views.”

“If you back down, people will take advantage of that. And that’s what happened to me,” Tong said. “You back down, your life’s ruined. Whether it’s physically, materially, or spiritually.”

Tong doesn’t believe anyone involved, whether Fordham or the critical students on social media, ever really feared that he might commit violence because he chose to take a photo with a gun.

Despite the “mean” messages — and even threats of violence — that he received on his Instagram posts, Tong said he got a lot of support, including a substantial amount from students who messaged him privately, for fear of retribution for championing him publicly.

As a Chinese immigrant whose family fled a repressive government — a country where college students like him have been murdered by the government for simply expressing their views — Tong worries that American students fighting against free expression don’t understand the gravity of what they’re doing.

Every time a student asks a university to investigate or punish a peer for simply expressing a controversial viewpoint, Tong argues, everyone’s right to free expression erodes a little more.

“Most countries in the world don’t have privileges that Americans have, which is the right to speak without any legal consequence,” Tong said. “They don’t understand that.”

So Tong says he will fight for the rights of his fellow students to speak out, even if a growing subset of them don’t seem to understand why doing so is important.

He hopes even students who disagree with his views, might be persuaded to support his right to express them. After all, Tong’s freedom to speak his mind on social media is the same as the right of his most virulent critic to do the same.

Fordham’s policies guarantee such freedoms for all students. At least in theory. Tong said he is committed to helping make those promises a reality. Other students, he adds, can help.

“I will say, for young people, the best thing you can do to hold these institutions accountable is to speak up about it,” Tong said. “And if they really did something wrong, sue them.”

Chinese companies often face questions regarding their legal obligations when actions arise in the U.S. involving products they manufactured. Attorneys advising Chinese companies on their legal obligations with respect to lawsuits in the U.S. must advise their clients on both the U.S. discovery process, which can be alien to Chinese companies, and the requirements under the Hague Convention on the Taking of Evidence Abroad in Civil or Commercial Matters (Hague Convention). Similarly, U.S. attorneys seeking discovery from Chinese individuals or corporations must understand the procedures and limitations of conducting discovery in China, which can be quite unfamiliar even to experienced attorneys.

Thus, PRC companies are often surprised to learn that despite not being a party to a lawsuit, they may be compelled to produce evidence in connection with litigation. The PRC Civil Procedure Law does not obligate third parties to provide evidence for a proceeding in which they have no interest. In the U.S., however, if a party is within a court’s jurisdiction, a court may order a non-party to a proceeding, through a subpoena, to produce documents or submit to a deposition which require responses under penalty of perjury.

Chinese manufacturers whose products make their way into the U.S. may become embroiled in U.S. litigation, either as a party to the suit or as a non-party subject to document requests during the discovery phase of litigation. It is important for these companies to understand that even if they are not subject to personal jurisdiction in the U.S., they may be sent “Letters of Request” under the Hague Convention requiring them to cooperate and provide evidence with a close connection to the subject matter of any lawsuits. Therefore, Chinese companies would be wise to seek the advice and potential protection of counsel in navigating the maze of U.S. discovery obligations and the challenges it presents.

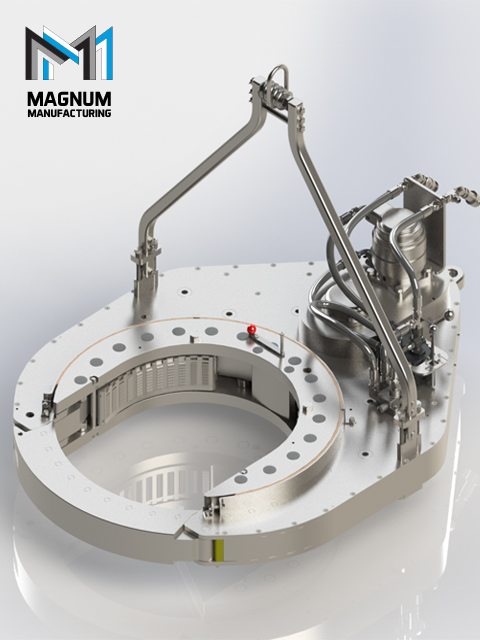

DC Power Tong continues to set the standard in the casing and tubing service industry by offering superior service & innovative casing technology. To exceed our customersʼ expectations, DC Power Tong also provides hydro test trucks, pressure test units, and equipment and pipe wrangler rentals to ensure your project is completed safely and efficiently. At DC Power Tong, we treat your project as if it is our very own, and thatʼs what weʼre all about.

1China’s laws and policies on the judicial review of government actions are often presented as an important bellwether of the government’s attitude towards the rule of law.1Accordingly, in the last few years, in gauging the direction of legal reform in the Xi Jinping era, media reports have highlighted changes in litigation against government agencies as evidence of positive movement towards the greater rule of law, albeit only contradicted by other evidence of political repression and increasing authoritarianism.2Regardless of whether the institution of judicial review can bear the symbolic weight that has thus been vested in it – we believe there are many reasons to be sceptical (Cui 2017) – the last few years have indeed witnessed very momentous changes in China’s administrative litigation system. In 2014, the Administrative Litigation Law (ALL) received its first amendment since its original adoption in 1989; the newly (and extensively) amended statute took effect on 1stMay 2015.3In 2018, China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) published a lengthy Interpretation on the Application of the Administrative Litigation Law (hereinafter the “2018 SPC Interpretation”), which replaced and substantially revised previous interpretations and ushered in a number of important doctrinal and institutional innovations. More generally, reforms carried out since 2014 of the Chinese judicial system – including especially the centralisation (to the provincial level) of court financing, re-allocation of jurisdiction to higher courts, the creation of new supra-provincial circuit courts, and dramatic changes to judges’ career incentives – all have had direct impact on the administrative tribunals that hear lawsuits against government agencies.

2The empirical reality of judicial review makes these statutory, doctrinal, and institutional changes even harder to ignore. The number of first-instance lawsuits against government agencies in China surged from 123,194 in 2013 to 230,432 in 2017, an increase of 87%; and the number of second-instance disputes (i.e., appeals) from such lawsuits increased even faster – 207%, or from 35,222 to 108,099.4On a per capita basis, the volume of administrative litigation in China already surpasses that of Taiwan,5and no doubt of some other countries where both democratic accountability and judicial independence are regarded as well established.

3In this essay, we provide a selective review of these recent changes in the doctrines and procedures of judicial review. Our review adopts a pragmatic and comparative approach. In our view, the question of whether lawsuits might be brought against the government has arguably become less interesting than the question of how courts will decide such lawsuits. And the generic notion of judicial independence itself no longer sheds sufficient light on the range of actual and possible judicial responses. However, many media and scholarly commentaries (both Chinese and Western) on judicial review in China remain fixated on symbolic values. Arguably, this fixation has given rise to institutional arrangements that threaten to diminish, rather than enhance, judicial authority.

7The SPC played an important role in this process. A book for which senior SPC judge Jiang Bixin江必新served as chief editor and co-author,Perfection of China’s Administrative Litigation System: A Practical Study for an ALL Revision, became a classic (Jiang 2005), and helped to frame many of the major issues in the debate in this area.7The view expressed in his book was as much institutional as it was personal.8Jiang identified four major issues as critical to reforming administrative litigation: (1) empowering the administrative tribunal, (2) nurturing a profession of administrative law judges, (3) achieving efficiency and inclusiveness of adjudication, and (4) enhancing jurisdictional flexibility (Jiang 2005: 9-12). The SPC’s influence on the ALL revision is visible through both the issues emphasised by the NPCSC during its deliberations and the structure of the revisions to the law. For example, when Xin Chunying信春鹰, vice director of the NPCSC Legislative Affairs Office, introduced the Draft Revision of the ALL on the last day of 2013, she mentioned the “three difficulties of adjudication” (i.e., of filing a case, of adjudicating a case, and of enforcing a decision rendered), which echoed the “three difficulties” originally formulated by Jiang in 2005 (Jiang 2005: 9-10). Many provisions of the Draft Revision were also anticipated in the 11 topics that structured Jiang’s book. Nonetheless, among the four critical issues identified by Jiang (and his SPC colleagues), the NPCSC prioritised issues of adjudication (including the so-called three difficulties), and hesitated to proceed with the first two structural issues (i.e. the roles of administrative tribunals and of judges).

11The 2015 ALL kept the original structure of the 1989 ALL, but was elaborated and enriched to contain 103 articles. Some major revisions are summarised below (Tong 2015: 22-7).

12Under the 2015 ALL, individuals, organisations, or legal persons may file a lawsuit if they believe that an “administrative action” violates their legal rights and interests (Article 2). The term “administrative action” replaced the term “concrete administrative action” in the 1989 ALL, although this drafting change has little significance in itself in expanding the scope of review. This is basically because the 2015 ALL retains a provision (Article 13) from the 1989 ALL that excludes four categories of government actions from judicial review – including formal and informal rulemaking. More substantively, Article 2 (2) extends the definition of “administrative action” to include decisions made by organisations authorised to exercise administrative mandates, such as universities and some regulatory bodies. In addition, Article 12 details 11 areas in which legal proceedings may be launched against governments, making explicit reference to violations of agreements on land and housing compensation, unlawful alteration or rescission of agreements on commercial operations franchised by the government, and illegal restriction of an individual’s physical freedom. While all government actions encroaching on the personal and property rights of plaintiffs can be challenged (before and after 2015), the new statutory enumeration seemed to identify areas where the need to cope with social resentment and unrest is most urgent.

15The 1989 ALL’s standard for standing was formulated subjectively – one may bring a suit if one “considers” that a concrete administrative action infringes on one’s lawful rights and interests (Article 2). A 2000 SPC’s Interpretation of the 1989 ALL stipulated that only those who possess legal rights and interests may bring a case – which was characterised by some as overly narrow (Jiang 2013: 9). The 2015 ALL aimed to resolve this controversy. It provides that a person subjected to an administrative action or any other person with an interest in the administrative action has the right to file a complaint (Article 25). The phrase “with an interest” is considered to be broader than “with legal rights and interests,” but narrower than “who considers his interest [violated]” (Tong 2015: 25).

20The 2015 ALL also adds mediation as a type of remedy. A traditional theory had it that government agencies were to enforce the law and should be prohibited from bargaining with individuals. That theory, however, has become anachronistic with government powers extending to many economic areas. Contemporary studies provide evidence that mediation mitigates conflicts and reduces administrative costs.15The 2015 revision reflects this new understanding of the functions of mediation in public law.

28Under pre-2015 law and practice, Chinese courts’ power to review regulations and other policy directives adopted by executive branch agencies took three main forms. First, if a regulation (guizhang规章) was offered as the legal basis of agency action, a court must determine whether the regulation was legal and in force before giving it application as law.21Second, if some “other normative document” (qita guifanxing wenjian其他规范性文件, which we refer to as informal policy document or IPD here) was offered as the legal basis of an agency action, such document had no binding force on courts. Courts could nevertheless give it effect after reviewing and confirming its legality, validity, reasonableness, and appropriateness.22That is, legality was not sufficient for an IPD to be given effect: a court had discretion to disregard IPDs based on judgments about their reasonableness and appropriateness – or it could even simply disregard them altogether, without review. Third and finally, there was a set of circumstances in which a court might suspend judicial proceedings and seek resolution of conflicts among formally binding legal rules, through interlocutory procedures that transmitted questions to the executive branch. One such circumstance was irresolvable conflicts among ministerial and subnational regulations,23but the interlocutory procedure was also available for a wider range of conflicts among other types of formally binding law.24

29It has long been conventional wisdom among commentators on Chinese administrative law that these parameters for judicial review were too restrictive (He 2018; Tong 2015). The restrictions most frequently criticised were two. First, Article 12(2) of the 1989 ALL explicitly ruled out lawsuits brought merely to challenge “administrative statutes and regulations, or decisions and orders with general binding force formulated and announced by administrative entities.” That is, agency adoption of formal or informal rules – colloquially labelled “abstract administrative actions” – could be causes of action, even if the rules adopted were suspected to be illegal, unreasonable, or otherwise flawed.25As discussed, this provision remains unchanged in the 2015 ALL, despite the fact that the 2014 amendment no longer refers to “specific administrative actions” in its provisions on permissible causes of action.

32The logic of the two restrictions on the scope of judicial review is best explained in reverse order. First, there is an obvious explanation why Chinese courts may not be permitted to “strike down” problematic agency rules. This has to do with the idea that civil law judiciaries, on which the Chinese judiciary is modelled, are generally expected to apply the law, not to make law. Relatedly, decisions by civil law courts generally do not have precedential value, because they do not create norms of general application. While some modern courts in civil law countries present exceptions to these general rules, the rules continue to characterise the power of most civil law courts. Precluding formal regulations from reinforcement clearly raises suspicions of both law-making (i.e., revoking binding law) and claiming to set precedents, while precluding IPDs from enforcement also sets precedents. This basic logic is supported by the fact that, in civil law countries, the ability of courts to invalidate agency rules seems to be the exception, not the rule.

33In Germany, for example, an administrative court, when assessing the lawfulness of an agency action, can review a regulation on which such act is based and may rule that it is inconsistent with higher law and therefore void. However, this is not a matter of “striking down” a regulation: it is an assessment of its validity as a preliminary question; such preliminary findings generally do not have any binding effect – not even between the parties to the lawsuit. Similarly, German courts generally do not review informal policy announcements but directly apply the law when assessing the lawfulness of government actions. Any assessment of the lawfulness of an informal rule constitutes a preliminary matter and therefore does not have any binding effect (Panzer 2017: 8; Schmitz 2018: 212-3; Lindner 2018: 30-2; Scherzberg and Seidl 2014).

36If a court cannot strike down formal or informal agency rules, it should also not hear disputes the main purpose of which is to challenge the validity of such rules – the reviewing court would not be able to provide any remedy. This simple logic already goes a long way toward justifying the non-justiciability of “abstract administrative actions.” Using US terminology, we will label the judicial review of an agency rule before its enforcement “pre-enforcement review.” From a comparative perspective, pre-enforcement review indeed requires extensions of the traditional powers of a civil law court.

37Again, we offer Germany as an example. The German Code of Administrative Court Procedure (VwGO) is widely known for a set of special provisions in Section 47 whereby most state regulations and municipal by-laws are subject to direct judicial review for up to a year after their enactment. An individual can bring a lawsuit challenging such regulations if s/he can demonstrate that the regulation and its enforcement potentially infringes upon her individual rights. If a higher administrative court finds a regulation to be void, by law, the ruling has effecterga omnes, i.e., not onlyvis-à-visthe parties to the lawsuit (Giesberts 2018: 65).This establishes an equivalent to precedential value. However, this is precisely understood to be a singular feature of Section 47 direct review, compared to the effect of other court decisions under German law. In contrast, federal regulations cannot be struck down by administrative courts with general effect. Finally, in general, informal policy announcements themselves cannot be subject to judicial pre-enforcement review due to their lack of legal effect. Only the acts based on such announcements will be reviewed by administrational and constitutional courts.

40Note from the outset that the standard of review is an important question, regardless of whether the reviewing court is of the civil or common law variety. Regardless of whether a court “merely” determines whether to apply a policy interpretation advocated by the government, or whether the court has the power to invalidate such an interpretation, the court needs to decide the standard to which the government’s position must be held. A comparison of four regimes – in China, the US, Canada, and Germany – suggests that the adoption of this standard depends not at all on constraints on the scope of review.

51The power of the judiciary to propose the amendment or revocation of IPDs (albeit only ones that are not in accordance with law) seems extraordinary. It is indeed unclear what basis a court has for imposing an obligation on the executive branch to respond. As if to strengthen its power to do so, the 2018 SPC Interpretation provides that if a court deems an IPD to be legally invalid, it is required to file the decision (post adjudication) with the court at the next higher level for the record.36Moreover, if an IPD promulgated by a department of the State Council or a provincial agency is involved, any judicial proposal made to the executive branch should also be submitted to provincial high courts and the SPC for record.37This seems to ensure that the finding of an illegal IPD will be escalated within the judiciary, and that first-instance courts are not left to their own devices to pursue the (rather entrepreneurial) undertaking of issuing recommendations to the executive branch.

54However, for several reasons, one must be cautious in drawing conclusions from these descriptions. First, much scholarly discussion in China about judicial review has engaged with proposals to revise the ALL, yet the ALL’s revision is, as we tried to show, clearly a matter of top-down institutional design, driven visibly by a small group of actors in the SPC and NPCSC. The question can be raised as to whether this sociological origin of the discourse on ALL has affected its content. For example, radical proposals that lack clear functional justification but that accentuate the symbolism of judicial review – such as creating a separate administrative court system, requiring agency chiefs to appear in court, and emboldening judges to constrain executive branch rulemaking – seem to attract perennial interest. At the same time, basic facts about how the thousands of court administrative divisions across China have handled cases tend to remain obscure – with the SPC acting as one of the few sources of information. Indeed, even the well-known “three difficulties” of bringing suits against agency defendants are not well-documented empirically: empirical accounts of what proportion of lawsuits had been declined by courts at the outset, for example, vary widely in their estimates. Therefore, it is important – especially for Western commentators – to recognise the existence of these gaps and not to conflate a stylised discourse on administrative litigation with its reality.

55Second, Chinese scholars and policymakers have yet to articulate a normative framework for conceptualising what forms enhanced judicial power should take. Should it, for example, be courts’ frequent use of various sanctions of agency misconduct in the course of litigation, of the power to make judicial recommendations for amending or repealing illegal IPDs, or of the authority to retry cases? Or should it, again for example, be the ability of individual judges to introduce policy considerations into adjudication through reviewing the reasonableness of IPDs (which the Shanghai Meeting Minutes contemplated but which the 2018 SPC Interpretation seems to abolish)? An important and common theme in contemporary administrative law scholarship in liberal democracies is how to preserve the integrity of judicial review while recognising the limitations of the judiciary within the modern state in the interpretation and enforcement of policy (Merrill and Hickman 2001; Hickman and Krueger 2007; Vermeule 2017; Stack 2018; Arai-Takahashi 2000; Schmitz 2018; Oster 2008; Decker 2018; Daly 2018). Arguably, this theme has largely been absent from Chinese discourse in reforming the ALL.

Protection of NFTs seems more problematic in China. It starts with the Chinese translation of Non-Fungible Tokens. The literal Chinese translation of NFT should be 非同质化代币 (Fei Tong Zhi Hua Dai Bi), an expression that contains the word token. Given that the Chinese government prohibits the transaction of virtual currencies, the Chinese market and users had to change this translation to avoid referring to crypto currencies as that could make NFTs illegal. To avoid this risk, the Chinese market has created a different Chinese name for NFTs: Digital Collection (数字藏品, hereafter also referred as “DC”).

Compared to NFTs as defined in the US, the DC in China: 1) are under strict market supervision that caps their valuation and pricing by avoiding social media hyping of the same; and 2) can only be purchased with Chinese currency, the Ren Min Bi (RMB) in the traditional or digital form.

Article 3 of the China Copyright Law defines copyrightable works as intellectual creations with originality in the realm of literature, art or science that can be represented in a certain form (the “tangibility” requirement in the US) and expands its scope by including other intellectual creations that meet the characteristics of works. NFTs/DC are indeed intellectual creations that can be represented in a certain form and therefore can be copyrightable in China as long as they possess originality and fit one of the listed categories of works. As it may be inferred from the Chinese name “Digital Collection” (数字藏品, the “DC”), most NFTs in China assume the form of works of art, photographic works, etc.

It has been debated whether NFTs/DC could be protected in China by design patents. The current tendency is that of denying protection to designs of non-physical products, like metaverses. However, given the recent developments in favor of extending design patent protection to metaverses in other Asian countries including Singapore, Japan, and South Korea, Chinese right holders have started filing design patents to protect digital creations which may include NFTS and metaverses. For more details on the topic of design and the metaverse in China see our previous blog post.

Legal practitioners and Chinese judges advocate that virtual property should be protected by reference to the rules on property rights, and the current rules of property law can apply to data. Therefore, it is also accepted that ownership of NFTs/DCs as intellectual work is regulated by the China Copyright Law and its Implementing Regulations.

These developments seem to point to the fact that: a) NFT’s, although restricted in their commercialization, are an emerging trend in China; b) statutory regulations can be expected soon to codify the latest trends; and c) NFT/DC ownership is regulated under the provisions of the Civil Code and the Copyright Law of the People’s Republic of China.

However, many NFTs/DCs are derived from physical works such as photographic works, works of art, etc. Unlike the situation in the US, there seems to be no weight given in China to the minting process as a possible generator of ownership. The Chinese practice seems to stick with the traditional principles of copyright ownership: the owner of the original physical works should still be the owner of the derived NFTs/DCs unless otherwise agreed by the involved parties.

In China, the transaction of the NFTs/DCs would not normally include the transfer of the related copyright. The buyer should therefore check with the seller (usually the NFT platform) to check his/her rights, and especially the copyright ownership or license rights. If no copyright ownership or license is obtained, the buyer should use the purchased NFT/DC only for private consumption in order to avoid bearing potential copyright infringement liabilities.

The display of the NFTs/DCs on the NFT trading platform for selling purposes (chaining) is considered by the law to be an act of “Information Network Transmission.” The entity or person chaining the NFT (which could be the miner) should thus bear liability for violation of the original copyrighted work, unless consent of the copyright holder has been obtained.

The first NFT copyright infringement lawsuit in China in 2022 [深圳奇策迭出文化创意有限公司诉某科技公司侵害作品信息网络传播权纠纷一案 ([2022]Zhe 0192 Min Chu No. 1008]was filed by Shenzhen Qice Diechu Cultural & Creative Co. Ltd. (hereafter referred to as Qice) against an NFT platform instead of the miner (probably because the miner’s identity was not accessible). In the judgment, the Hangzhou Internet court determined that the NFT platform is fully and vicariously liable. An NFT works with a selling price of 899RMB used the original animation IP without authorization, and the trading platform was awarded a compensation of 4000 RMB (NFT作品擅用动漫IP原图标价899元,交易平台被判赔4000元,NFTCN主体与原告存在侵权纠). Interestingly, the court did not find liability of the platform based on the Copyright Law (that would have applied to the miner), but instead resorted to the general principle of negligent tort. The NFT platform had the ability to confirm that the NFT contained work from an author whose name was indicated by a watermark in the microblog account and in the description of the original picture. The NFT platform failed to verify whether the miner was the copyright owner of the accused infringing NFT digital works or check the relation between the foresaid registered owner and the original author.

The NFT platform was ordered by the court to disconnect the block chain of the infringing NFT digital works and put it in the address black hole to achieve the legal effect of stopping infringement (an injunction), and to pay damages of 4,000RMB (US$548). The selling price of the infringing NFT digital works was only 899RMB and there had only been one transaction at the time the lawsuit was filed.

In conclusion, even if the Copyright Law of China seems the closest legal base to obtain protection for NFTs, the only relevant judicial decision so far has instead found the NFT platform liable on the tort principles of the civil code and has not even considered the liability of the miner in this case. Also, damages were rather symbolic and would surely not justify the cost to file a lawsuit —at least not one that omits the miner and the one chaining the infringing NFT (which could be the same entity/person as the miner).

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Robert Drain must approve the deal, which protects the Sacklers from civil lawsuits. Purdue requested a March 9 hearing for Drain to review the agreement.

Opioid overdose deaths soared to a record during the COVID-19 pandemic, including from the powerful synthetic painkiller fentanyl, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said.

Purdue filed for bankruptcy in 2019 in the face of thousands of lawsuits accusing it and members of the Sackler family of fueling the opioid epidemic through deceptive marketing of its highly addictive pain medicine.

Tong and the mediator urged Drain to allow victims of the opioid epidemic to address the court when the judge considers approving the settlement and to order the Sackler family members to attend.

U.S. district and circuit courts were created by the Judiciary Act of September 24, 1789. The jurisdiction and powers of these Federal courts have varied with subsequent legislation, but district courts have been principally criminal, admiralty, and bankruptcy courts, hearing noncapital criminal proceedings, suits for penalties or seizures under Federal laws, and litigation involving an amount in excess of $100 in which the United States is the plaintiff. The circuit courts heard appeals from the district courts and were given exclusive original jurisdiction over actions involving aliens, suits between citizens of different States, and law and equity suits where the amount in dispute exceeded $500. In 1891 the appellate jurisdiction of the circuit courts was transferred to the newly created courts of appeals (see RG 276). The Judiciary Act of 1911 abolished the circuit courts and provided for the transfer of their records and remaining jurisdiction to the district courts.

Most States initially had one district and one circuit court with additional districts and subdivisions created as the business of the courts increased. In 1812 circuit courts were authorized to appoint U.S. commissioners to assist in taking bail and affidavits. Commissioners" functions were expanded by subsequent legislation and court rules. Their powers have included authority to issue arrest warrants, examine persons charged with offenses against Federal laws, initiate actions in admiralty matters, and institute proceedings for violation of civil rights legislation.

Records of the Chung Shin Tong, Lung Doo Section, c. 1943-1951 (unnumbered microfilm.) Arranged by type of record (membership lists, membership receipts, or minute books), thereunder chronologically by year.

![]()

Robinson failed to pay the Hubei judgment. On March 24, 2006, the Chinese companies then started a new action in California federal court to collect the judgment. Almost one year later, the court granted summary judgment in favor of Robinson on the grounds that the statute of limitations had expired before the Chinese lawsuit was filed. The Chinese companies appealed the judgment to a US appellate court, which ruled that the PRC action was not barred by the statute of limitations, and that “there was no basis for finding that enforcement of the PRC judgment would violate California’s public policy against stale claims.” In August 2009, judgment was issued in favor of the Chinese companies, enforcing the Hubei judgment. Robinson moved for a new trial, but that request was denied.

Almost five years after the federal district court ruled against Robinson, petitioner Liu Li filed a lawsuit in California state court alleging breach of an Equity Transfer Agreement and fraudulent misappropriation of $125,000 by respondents Tao Li and Tong Wu. The respondents did not show up and a default judgment was issued in favor of Liu Li. Thereafter, Liu Li sought to enforce the California judgment in the Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court, PRC, where Tao Li and Tong Wu resided.

Now we may know the answer to the last question: According to the new lawsuit, Matinee Energy officials stole $1.6 million from JES Solar of Korea for the purported Benson project.

Tong"s a former Clinton Administration official, former counsel to South Korea"s current president, Lee Myung-bak, and the former head of Invest Korea, the country"s national investment promotion firm. Tong helped found the California law firm Lim Ruger & Kim, LLP, but is now based in Korea.

He did not return e-mails from New Times seeking comment. A New Times reader sent us a picture that purportedly shows Tong attending one of last year"s bogus "ground-breaking" ceremonies in Benson. We can"t confirm that"s Tong in the picture; we sent it to Tong by e-mail and, again, he has not replied.

JES Solar, founded in Korea in 2007, states in its lawsuit (see below) that Tong"s "presence and purported involvement" in Matinee Energy influenced JES" decision to advance $1.6 million to Matinee.

The money was supposed to give JES a partial ownership in what Matinee claimed would be a $160 million solar project. In reality, the lawsuit states, Matinee "lacked sufficient funds" to build the plant at all.

Matinee officials including Chin Kim and Paul Jeong led JES Solar to believe that JP Morgan Chase was on board to lend Matinee the capital it needed. At Matinee"s October 2011 ceremony in a patch of desert in Benson, Chin introduced Tong Soo Chung as "Matinee"s official agent for the Asia region."

At the ceremony, Chin "sobbed and hugged ... Tong and engaged in other theatrics to express their enthusiasm and gratitude for the solar plant project," the lawsuit states.

It makes sense that someone with Tong"s credentials might be be involved with Matinee -- after all, the company at one point had signed contracts with Hyundai Heavy, the world"s largest shipbuilder, and KEPCO KDN, Korea"s national IT company, for Arizona solar projects. Those deals, as our previous story explained, are now dead.

After Matinee began making excuses in November 2011 for its failure to secure the JP Morgan financing, JES began investigating Matinee, the lawsuit says. JES soon came upon our August 2010 article about Matinee Energy, which referenced Matinee Energy"s connection to a gold-mining scam from the 1980s. No doubt, it would have been better to find that article before making the decision to give Matinee $1.6 million.

We"ll keep you posted on how that lawsuit progresses. It"s actually the second suit against Matinee in as many months. On July 31, Chinese solar-panel maker Lightway sued Matinee for $4.4 million in federal court in New Jersey.

8613371530291

8613371530291