dc power tong casing lawsuit price

DC Power Tong continues to set the standard in the casing and tubing service industry by offering superior service & innovative casing technology. To exceed our customersʼ expectations, DC Power Tong also provides hydro test trucks, pressure test units, and equipment and pipe wrangler rentals to ensure your project is completed safely and efficiently. At DC Power Tong, we treat your project as if it is our very own, and thatʼs what weʼre all about.

DC Power Tong has been providing power tong and casing services since 2012. We specialize in Casing and Tubing work primarily in the Bakken and surrounding areas. For all your casing or pressure test needs, contact us at DC Power Tong today!

(Hartford, CT) -- Attorney General William Tong today announced a $230 million multistate settlement with Mallinckrodt regarding allegations the company knowingly underpaid Medicaid rebates for its drug H.P. Acthar Gel. Connecticut is joined in the settlement by 49 other states, Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, and the federal government.

“Mallinckrodt raised its Acthar price and lied about the gel’s status as a ‘new drug’ to avoid paying millions of dollars in rebates to state Medicaid programs. Acting in coordination with our multistate partners and the federal government, we are now holding Mallinckrodt accountable for those false claims and forcing them to pay $230 million,” said Attorney General Tong.

This settlement results from a whistleblower lawsuit originally filed in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts. The federal government, twenty-six states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico intervened in the civil action in 2020. The settlement, which is based on Mallinckrodt’s financial condition, required final approval of the U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the District of Delaware, which approved the settlement on March 2, 2022.

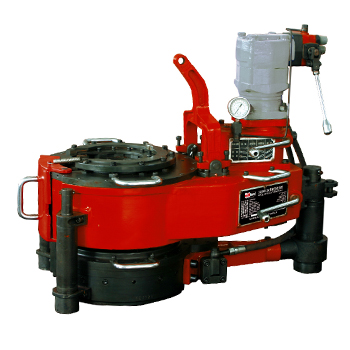

WILLISTON, N.D. – Heller Casing has been cited by the U.S. Department of Labor"s Occupational Safety and Health Administration for two general duty clause safety violations after a worker was fatally crushed Jan. 31 while installing casing pipe on an oil rig in McKenzie County. The incident occurred when the worker was struck by an improperly secured load that fell, causing fatal injuries.

"Heller Casing has a responsibility to protect oil rig workers from struck-by and other hazards in this dangerous industry," said Eric Brooks, OSHA"s area director in Bismarck. "No job should cost a person"s life because an employer failed to properly protect and train workers."

OSHA cited two serious violations directly related to the fatality that involved failing to protect workers from struck-by and crushing hazards by properly securing the hook used to suspend a load, which consisted of power tongs and accurately positioning the suspension cable. The power tongs allegedly became snagged on the traveling block as it was being elevated. The tongs loosened from the block after being elevated about 15 feet and fell on the victim.

Proposed fines total $14,000. Heller Casing has 15 business days from receipt of the citations to comply, request an informal conference with OSHA"s area director, or contest the citations and penalties before the independent Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission.

WILLISTON, N.D. – Heller Casing has been cited by the U.S. Department of Labor"s Occupational Safety and Health Administration for two general duty clause safety violations after a worker was fatally crushed Jan. 31 while installing casing pipe on an oil rig in McKenzie County. The incident occurred when the worker was struck by an improperly secured load that fell, causing fatal injuries.

"Heller Casing has a responsibility to protect oil rig workers from struck-by and other hazards in this dangerous industry," said Eric Brooks, OSHA"s area director in Bismarck. "No job should cost a person"s life because an employer failed to properly protect and train workers."

OSHA cited two serious violations directly related to the fatality that involved failing to protect workers from struck-by and crushing hazards by properly securing the hook used to suspend a load, which consisted of power tongs and accurately positioning the suspension cable. The power tongs allegedly became snagged on the traveling block as it was being elevated. The tongs loosened from the block after being elevated about 15 feet and fell on the victim.

Proposed fines total $14,000. Heller Casing has 15 business days from receipt of the citations to comply, request an informal conference with OSHA"s area director, or contest the citations and penalties before the independent Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission.

U.S. Bankruptcy Judge Robert Drain must approve the deal, which protects the Sacklers from civil lawsuits. Purdue requested a March 9 hearing for Drain to review the agreement.

Opioid overdose deaths soared to a record during the COVID-19 pandemic, including from the powerful synthetic painkiller fentanyl, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said.

Purdue filed for bankruptcy in 2019 in the face of thousands of lawsuits accusing it and members of the Sackler family of fueling the opioid epidemic through deceptive marketing of its highly addictive pain medicine.

Tong and the mediator urged Drain to allow victims of the opioid epidemic to address the court when the judge considers approving the settlement and to order the Sackler family members to attend.

SEC v. Gianluca Di Nardo, Corralero Holdings, Inc., Oscar Ronzoni, Paolo Busardo, Tatus Corp., and A-Round Investment SA (originally filed as SEC v. One or More Purchasers of Call Options for the Common Stock of DRS Technologies, Inc. and American Power Conversion Corp.)

October 2022 — New Jersey Attorney General Matthew Platkin filed a lawsuit against ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, BP, ConocoPhillips, and the American Petroleum Institute for the damage that their climate deception is causing to communities across the state.

September, 2020 — Delaware Attorney General Kathy Jennings filed a lawsuit against 31 fossil fuel companies “to hold them accountable for decades of deception about the role their products play in causing climate change, the harm that is causing in Delaware, and for the mounting costs of surviving those harms.”

September 2020 — The City of Charleston is suing 24 fossil fuel companies to hold them accountable for lying about climate change harms they knowingly caused — and to make them pay a fair share of the damage. Charleston’s was the first such lawsuit filed in the American South.

September 2020 — Hoboken, the coastal “Mile Square City,” is the first municipality to file a climate liability lawsuit in New Jersey. The city’s lawsuit argues that ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron, ConocoPhillips and the American Petroleum Institute’s climate deception violates the state’s consumer fraud statute and provides grounds for common law claims of public and private nuisance, trespass and negligence.

Attorney General William Tong is filing suit in Hartford Superior Court against ExxonMobil, considered the grandaddy of the companies now accused of knowing for decades their products contributed to the emissions that cause global warming and climate change, but hiding it from the public.

“ExxonMobil sold oil and gas, but it also sold lies about climate science. ExxonMobil knew that continuing to burn fossil fuels would have a significant impact on the environment, public health and our economy. Yet it chose to deceive the public,” Tong said.

Connecticut is suing under the Connecticut Unfair Trade Practices Act, the law the state used to make a similar successful claim against the tobacco industry. It alleges an ongoing, systematic campaign of lies and deception. The three-year statute of limitations for private actions under the law does not apply to the state government. That will allow the attorney general to access documents going back to the 1950s that some previous lawsuits may not have been able to use.

Tong announced the lawsuit on a deck overlooking New Haven Harbor, a fuel tank farm across the water forming a backdrop. He was joined by officials in the administration of Gov. Ned Lamont, whom Tong says is “150%” in support.

Documents detailing Big Oil’s understanding of the industry’s role in climate change go back decades. They were first shown to exist in 2015 in stories by Inside Climate News and the Los Angeles Times. Tong said that his case “draws heavily from Exxon’s and Mobil’s own historical internal memos, which plainly convey the companies’ firm understanding of the connection between fossil fuel consumption and climate change.”

Tong and the head of his environmental unit, Matthew Levin, said the lawsuit was based on evidence already in the public record, but they declined to cite specific sources. Tong expects they are only “the top of the iceberg” and pre-trial discovery will uncover more evidence.

Since 2015, nearly two-dozen lawsuits have been filed by a few states and a number of counties and cities, with another dozen states — including Connecticut — supporting some of those suits. The most recent lawsuit was filed by Hoboken, N.J. earlier this month.

“We tried to think long and hard about what our best and most impactful contribution would be,” Tong said. “And what we settled on was a single defendant with a very simple claim: Exxon knew, and they lied.”

Tong’s interest in applying the big tobacco litigation blueprint to big oil and climate change was evident from his first months in office, when he told the CT Mirror that he was already thinking about it.

“There was no more powerful industry than tobacco,” he said. “If anybody thought a merry band of state attorneys general would fundamentally change the face of the worst public health crisis in the history of this nation as lawyered-up and well-resourced as they were, the prospects for success were pretty dim. And they did it.”

Connecticut and Delaware have joined a growing list of states, cities and counties that have filed climate change lawsuits against the fossil fuel industry, claiming oil and gas companies knew their products caused sea level rise and stronger hurricanes and willfully misled the public about those and other dangers related to global warming.

Connecticut’s lawsuit, filed Monday, named ExxonMobil as a sole defendant, while the lawsuit filed on Friday by Delaware named 31 fossil fuel companies and trade groups. They joinedMassachusetts, Rhode Island and Minnesota as states that have filed such litigation.

Former Vice President Joe Biden, who served 36 years as a senator from Delaware, cited the state’s lawsuit in aclimate change address on Monday to underscore the costs of global warming and the Trump Administration’s failure to address the issue. He called Trump, who was surveying the devastation of wildfires in California, a “climate arsonist.”

The coastal city of Charleston, South Carolina, also filed a climate lawsuit last week, joining close to 20 other cities and counties seeking to hold the fossil fuel industries liable for damages resulting from increased flooding and precipitation, droughts and intensifying storm surges, in addition to sea level rise and stronger hurricanes. The other cities include Baltimore, Oakland, San Francisco and Washington, D.C.

In Connecticut’s suit filed Monday, Attorney General William Tong sued Exxon for violating the state’s Unfair Trade Practices Act, which allows for wide-ranging claims of public and private nuisance, trespass, negligence and for violating its Consumer Fraud Act.

“ExxonMobil sold oil and gas, but it also sold lies about climate science,” Tong said when announcing the multi-billion dollar climate lawsuit against the company.

This spate of lawsuits comes after a series of recent rulings in similar cases that appear to give the advantage to states, counties and cities, legal scholars say.

The lawsuits also may send further tremors through the financial world that this summer has seenExxon dropped from the Dow Jones Industrial Average and a U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission report that concluded climate change threatens U.S. financial markets, those experts say.

Unlike the other climate lawsuits confronting the oil and gas industry that sweep up the world’s largest producers, the Connecticut lawsuit singles out Exxon as the sole defendant because the company’s deceptive record is well established, Tong said in an email interview.

“ExxonMobil is a leader in the industry and has been for decades,” Tong said. “We have evidence that shows that Exxon knew from its own scientists that climate change was occurring, made a deliberate decision to deceive consumers, and then successfully implemented that plan over the course of decades.

The climate lawsuits citean InsideClimate News series and a later Los Angeles Times story that revealed the extent of Exxon’s knowledge about the central role of fossil fuels in causing climate change as far back as the 1970s, based on research performed by its own scientists.

“ExxonMobil’s campaign of deception has contributed to myriad negative consequences in Connecticut, including but not limited to sea level rise, flooding, drought, increases in extreme temperatures and severe storms, decreases in air quality, contamination of drinking water, increases in spread of disease, and severe economic consequences,” Connecticut’slawsuit says.

The lawsuit seeks money to pay for defending against climate change threats, restitution for remediation costs already made, disgorgement of corporate profits, civil penalties and disclosure of all climate research.

Although the industry will no doubt put up a strenuous fight against these lawsuits, its chances of winning them have been diminished by a series of court rulings favorable to the plaintiffs, said Richard Frank, director of the California Environmental Law & Policy Center at the University of California, Davis School of Law.

Thefirst salvo in the legal war was fired in 2017 when Marin and San Mateo counties, near San Francisco, and the city of Imperial Beach, south of San Diego, filed climate lawsuits and drew national attention for daring to take on the powerful fossil fuel industry.

A ripple from the mounting number of lawsuits could be the further weakening of the oil industry’s standing in financial markets, said Pat Parenteau, a professor of environmental law at the Vermont Law School.

While the states, cities and counties, for the most part, want their lawsuits heard in state courts, the industry prefers the federal courts as a venue so that they can arguethe Clean Air Act and other federal laws preempt any claim under state law that carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels cause climate change and related property damage.

Delaware’s lawsuit against 31 fossil fuel entities and trade groups claims negligent failure to warn, trespass, public nuisance and multiple violations of Delaware’s Consumer Fraud Act. It seeks monetary damages to compensate the state and punish the companies, including $10,000 per violation of the Consumer Fraud Act.

“Defendants have known for decades that climate change impacts could be catastrophic, and that only a narrow window existed to take action before the consequences would be irreversible,” Democrat Kathy Jennings, the Delaware attorney general, says in the lawsuit

At the heart ofthe lawsuit is the matter of who will pay for the mounting financial, environmental and public health costs of the climate crisis, Jennings said during a news conference announcing the lawsuit.

The lawsuit further blasts the industry for falsely claiming through advertising campaigns … that their businesses are substantially invested in lower carbon technologies and renewable energy sources.

“In truth, each Fossil Fuel Defendant has invested minimally in renewable energy while continuing to expand its fossil fuel production … None of Fossil Fuel Defendants’ fossil fuel products are ‘green’ or ‘clean’ because they all continue to ultimately warm the planet,” according to the lawsuit.

“These special-interest-promoted lawsuits designed to punish a few companies who lawfully deliver affordable, reliable and ever cleaner energy undermine real efforts to address the complex policy issues presented by global climate change,” Chevron spokesperson Sean Comey said in an email. “There is no evidence Chevron misled the public about climate change. Those claims are false.”

The Charleston lawsuit seeks to hold two dozen major oil and pipeline companies accountable for climate change damages to the city. The lawsuit claims their products and the spread of misinformation about fossil fuels have caused increasing and disastrous flooding.

“As a direct and proximate consequence of Defendants wrongful conduct described in this complaint, the environment in and around Charleston is changing, with devastating adverse impacts on the City and its residents,” according tothe lawsuit, which asserts six causes of action, including public and private nuisance, strict liability and negligent failure to warn, trespass and violations of South Carolina’s Unfair Trade Practices Act

The City has incurred significant costs on capital projects to address sea level rise, including rebuilding its aging Low Battery Seawall, installing check valves to prevent tidal intrusion on the City’s storm drain system and redesigning and retrofitting its floodwater drainage system to keep up with increased flooding caused by sea level rise, including by constructing more than 8,000 feet of new drainage tunnels, according to the lawsuit.

Says Charleston’s lawsuit: “The City seeks to ensure that the parties who have profited from externalizing the consequences and costs of dealing with global warming and its physical, environmental, social, and economic consequences, bear the costs of those impacts on Charleston, rather than the City, taxpayers, residents, or broader segments of the public.”

United States Court of Appeals FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT Argued October 8, 2020 Decided January 19, 2021 No. 19-1140 AMERICAN LUNG ASSOCIATION AND AMERICAN PUBLIC HEALTH ASSOCIATION, PETITIONERS v. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY AND ANDREW WHEELER, ADMINISTRATOR, RESPONDENTS AEP GENERATING COMPANY, ET AL., INTERVENORS Consolidated with 19-1165, 19-1166, 19-1173, 19-1175, 19-1176, 19-1177, 19-1179, 19-1185, 19-1186, 19-1187, 19-1188 On Petitions for Review of a Final Action of the Environmental Protection Agency Steven C. Wu, Deputy Solicitor General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of New York, argued the cause for the State and Municipal petitioners and intervenor Nevada. 2 With him on the briefs were Letitia James, Attorney General, Barbara D. Underwood, Solicitor General, Matthew W. Grieco, Assistant Solicitor General, Michael J. Myers, Senior Counsel, Andrew G. Frank, Assistant Attorney General of Counsel, Xavier Becerra, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of California, Robert W. Byrne, Senior Assistant Attorney General, David A. Zonana, Supervising Deputy Attorney General, Jonathan A. Wiener, M. Elaine Meckenstock, Timothy E. Sullivan, Elizabeth B. Rumsey, and Theodore A.B. McCombs, Deputy Attorneys General, William Tong, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Connecticut, Matthew I. Levine and Scott N. Koschwitz, Assistant Attorneys General, Kathleen Jennings, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Delaware, Valerie S. Edge, Deputy Attorney General, Philip J. Weiser, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Colorado, Eric R. Olson, Solicitor General, Robyn L. Wille, Senior Assistant Attorney General, Clare E. Connors, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Hawaii, William F. Cooper, Deputy Attorney General, Aaron M. Frey, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Maine, Laura E. Jensen, Assistant Attorney General, Brian E. Frosh, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Maryland, John B. Howard, Jr., Joshua M. Segal, and Steven J. Goldstein, Special Assistant Attorneys General, Maura Healey, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Melissa A. Hoffer and Christophe Courchesne, Assistant Attorneys General, Megan M. Herzog and David S. Frankel, Special Assistant Attorneys General, Dana Nessel, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Michigan, Gillian E. Wener, Assistant Attorney General, Keith Ellison, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Minnesota, Peter N. Surdo, Special Assistant Attorney 3 General, Aaron D. Ford, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Nevada, Heidi Parry Stern, Solicitor General, Gurbir S. Grewal, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of New Jersey, Lisa J. Morelli, Deputy Attorney General, Hector Balderas, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of New Mexico, Tania Maestas, Chief Deputy Attorney General, Joshua H. Stein, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of North Carolina, Asher Spiller, Assistant Attorney General, Ellen F. Rosenblum, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Oregon, Paul Garrahan, Attorney-in-Charge, Steve Novick, Special Assistant Attorney General, Josh Shapiro, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Ann R. Johnston, Senior Deputy Attorney General, Aimee D. Thomson, Deputy Attorney General, Peter F. Neronha, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Rhode Island, Gregory S. Schultz, Special Assistant Attorney General, Thomas J. Donovan, Jr., Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Vermont, Nicholas F. Persampieri, Assistant Attorney General, Mark Herring, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Virginia, Donald D. Anderson, Deputy Attorney General, Paul Kugelman, Jr., Senior Assistant Attorney General and Chief, Environmental Section, Caitlin Colleen Graham O=Dwyer, Assistant Attorney General, Robert W. Ferguson, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Washington, Christopher H. Reitz and Emily C. Nelson, Assistant Attorneys General, Joshua L. Kaul, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Wisconsin, Gabe Johnson-Karp, Assistant Attorney General, Karl A. Racine, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia, Loren L. AliKhan, Solicitor General, Tom Carr, City Attorney, Office of the City 4 Attorney for the City of Boulder, Debra S. Kalish, Senior Counsel, Mark A. Flessner, Corporation Counsel, Office of the Corporation Counsel for the City of Chicago, Benna Ruth Solomon, Deputy Corporation Counsel, Jared Policicchio, Supervising Assistant Corporation Counsel, Kristin M. Bronson, City Attorney, Office of the City Attorney for the City and County of Denver, Lindsay S. Carder and Edward J. Gorman, Assistant City Attorneys, Michael N. Feuer, City Attorney, Office of the City Attorney for the City of Los Angeles, Michael J. Bostrom, Assistant City Attorney, James E. Johnson, Corporation Counsel, New York City Law Department, Christopher G. King, Senior Counsel, Marcel S. Pratt, City Solicitor, City of Philadelphia Law Department, Scott J. Schwarz and Patrick K. O’Neill, Divisional Deputy City Solicitors, and Thomas F. Pepe, City Attorney, City of South Miami. Morgan A. Costello and Brian M. Lusignan, Assistant Attorneys General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of New York, Gavin G. McGabe, Deputy Attorney General, Anne Minard, Special Assistant Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of New Mexico, Cynthia M. Weisz, Assistant Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Maryland, entered appearances. Kevin Poloncarz argued the cause for Power Company Petitioners. With him on the briefs were Donald L. Ristow and Jake Levine. Mark W. DeLaquil argued the cause for Coal Industry Petitioners. With him on the briefs were Shay Dvoretzky, Charles T. Wehland, Jeffery D. Ubersax, Robert D. Cheren, and Andrew Grossman. 5 Theodore Hadzi-Antich argued the cause for Robinson Enterprises Petitioners. With him on the briefs were Robert Henneke and Ryan D. Walters. Sean H. Donahue and Michael J. Myers argued the causes for Public Health and Environmental Petitioners. On the briefs were Ann Brewster Weeks, James P. Duffy, Susannah L. Weaver, Joanne Spalding, Andres Restrepo, Vera Pardee, Clare Lakewood, Howard M. Crystal, Elizabeth Jones, Brittany E. Wright, Jon A. Mueller, David Doniger, Benjamin Longstreth, Melissa J. Lynch, Lucas May, Vickie L. Patton, Tomas Carbonell, Benjamin Levitan, Howard Learner, and Scott Strand. Alejandra Nunez entered an appearance. David M. Williamson argued the cause and filed the briefs for Biogenic Petitioners. Gene Grace, Jeff Dennis, and Rick Umoff were on the brief for petitioners American Wind Energy Association, et al. Theodore E. Lamm and Sean B. Hecht were on the brief for amicus curiae Thomas C. Jorling in support of petitioners. Gabriel Pacyniak, Brent Chapman, and Graciela Esquivel were on the brief for amici curiae the Coalition to Protect America=s National Parks and the National Parks Conservation Association in support of petitioners. Deborah A. Sivas and Matthew J. Sanders were on the brief for amici curiae Administrative Law Professors in support of petitioners. Hope M. Babcock was on the brief for amici curiae the American Thoracic Society, et al. in support of petitioners. 6 Richard L. Revesz and Jack Lienke were on the brief for amicus curiae the Institute for Policy Integrity at New York University School of Law in support of petitioners. Steph Tai was on the brief for amici curiae Climate Scientists in support of petitioners. Michael Burger and Collyn Peddie were on the brief for amici curiae the National League of Cities, et al. in support of petitioners. Keri R. Steffes was on the brief for amici curiae Faith Organizations in support of petitioners. Shaun A. Goho was on the brief for amici curiae Maximilian Auffhammer, et al. in support of petitioners. Ethan G. Shenkman and Stephen K. Wirth were on the brief for amici curiae Patagonia Works and Columbia Sportswear Company in support of petitioners. Mark Norman Templeton, Robert Adam Weinstock, Alexander Valdes, and Benjamin Nickerson were on the brief for amicus curiae Professor Michael Greenstone in support of petitioners. Nicole G. Berner and Renee M. Gerni were on the brief for amicus curiae the Service Employees International Union in support of petitioners. Elizabeth B. Wydra, and Brianne J. Gorod were on the brief for amici curiae Members of Congress in support of petitioners. 7 Jonas J. Monast was on the brief for amici curiae Energy Modelers in support of petitioners. Katherine Konschnik was on the brief for amici curiae Former Commissioners of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in support of petitioners. Michael Landis, Elizabeth S. Merritt, and Wyatt G. Sassman were on the brief for amici curiae Environment America and National Trust for Historic Preservation in support of petitioners. Cara A. Horowitz was on the brief for amici curiae Grid Experts in support of petitioners. Eric Alan Isaacson was on the brief for amici curiae U.S. Senators in support of petitioners. Jonathan D. Brightbill, Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice, and Meghan E. Greenfield and Benjamin Carlisle, Attorneys, argued the causes for respondents. With them on the brief was Jeffrey Bossert Clark, Assistant Attorney General. Lindsay S. See, Solicitor General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of West Virginia, argued the cause for State and Industry intervenors in support of respondents regarding Affordable Clean Energy Rule. With her on the brief were Patrick Morrisey, Attorney General, Thomas T. Lampman, Assistant Solicitors General, Thomas A. Lorenzen, Elizabeth B. Dawson, Rae Cronmiller, Kevin G. Clarkson, Attorney General at the time the brief was filed, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Alaska, Clyde Sniffen Jr., Attorney General, Leslie Rutledge, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Arkansas, Nicholas J. 8 Bronni, Solicitor General, Vincent M. Wagner, Deputy Solicitor General, Dylan L. Jacobs, Assistant Solicitor General, Steve Marshall, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Alabama, Edmund G. LaCour, Jr., Solicitor General, Christopher M. Carr, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Georgia, Andrew A. Pinson, Solicitor General, Derek Schmidt, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Kansas, Jeffrey A. Chanay, Chief Deputy Attorney General, Curtis T. Hill, Jr., Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General of Indiana, Thomas M. Fisher, Solicitor General, Andrew Beshear, Governor, Office of the Governor for the Commonwealth of Kentucky, S. Travis Mayo, Chief Deputy General Counsel, Taylor Payne, Deputy General Counsel, Joseph A. Newberg, Deputy General Counsel and Deputy Executive Director, Jeff Landry, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Louisiana, Elizabeth B. Murrill, Solicitor General, Harry J. Vorhoff, Assistant Attorney General, Eric S. Schmitt, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Missouri, D. John Sauer, Solicitor General, Julie Marie Blake, Deputy Solicitor General, Timothy C. Fox, Attorney General at the time the brief was filed, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Montana, Matthew T. Cochenour, Deputy Solicitor General, Wayne Stenehjem, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of North Dakota, Paul M. Seby, Special Assistant Attorney General, Douglas J. Peterson, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Nebraska, Justin D. Lavene, Assistant Attorney General, Dave Yost, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General of the State of Ohio, Benjamin M. Flowers, Solicitor General, Cameron F. Simmons, Principal Assistant Attorney General, Mike Hunter, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Oklahoma, Mithun Mansinghani, Solicitor General, Jason R. Ravnsborg, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney 9 General for the State of South Dakota, Steven R. Blair, Assistant Attorney General, Alan Wilson, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of South Carolina, James Emory Smith, Jr., Deputy Solicitor General, Ken Paxton, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Texas, Kyle D. Hawkins, Solicitor General, Sean Reyes, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Utah, Tyler R. Green, Solicitor General, Bridget Hill, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Wyoming, James Kaste, Deputy Attorney General, Todd E. Palmer, William D. Booth, Obianuju Okasi, Carroll W. McGuffey, III, Misha Tseytlin, C. Grady Moore, III, Julia Barber, F. William Brownell, Elbert Lin, Allison D. Wood, Scott A. Keller, Jeffrey H. Wood, Jeremy Evan Maltz, Steven P. Lehotsky, Michael B. Schon, Emily Church Schilling, Kristina R. Van Bockern, David M. Flannery, Kathy G. Beckett, Edward L. Kropp, Amy M. Smith, Janet J. Henry, Melissa Horne, Angela Jean Levin, Eugene M. Trisko, John A. Rego, Reed W. Sirak, Michael A. Zody, Jacob Santini, Robert D. Cheren, Mark W. DeLaquil, and Andrew M. Grossman. C. Frederick Beckner, III, James R. Bedell, Margaret C. Campbell, Erik D. Lange, and John D. Lazzaretti entered an appearance. James P. Duffy argued the cause for Public Health and Environmental Intervenors in support of respondents. With him on the brief were Ann Brewster Weeks, Sean H. Donahue, Susannah L. Weaver, Joanne Spalding, Andres Restrepo, Vera Pardee, Clare Lakewood, Elizabeth Jones, Brittany E. Wright, Jon A. Mueller, David Doniger, Benjamin Longstreth, Melissa J. Lynch, Lucas May, Vickie L. Patton, Tomas Carbonell, Benjamin Levitan, Howard Learner, and Scott Strand. Letitia James, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of New York, Michael J. Myers, Senior Counsel, Brian Lusignan, Assistant Attorney General of 10 Counsel, Barbara D. Underwood, Solicitor General, Steven C. Wu, Deputy Solicitor General, Matthew W. Grieco, Assistant Solicitor General, Xavier Becerra, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of California, Robert W. Byrne, Senior Assistant Attorney General, David A. Zonana, Supervising Deputy Attorney General, Jonathan A. Wiener, M. Elaine Meckenstock, Timothy E. Sullivan, Elizabeth B. Rumsey, and Theodore A.B. McCombs, Deputy Attorneys General, William Tong, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Connecticut, Matthew I. Levine and Scott N. Koschwitz, Assistant Attorneys General, Kathleen Jennings, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Delaware, Valerie S. Edge, Deputy Attorney General, Philip J. Weiser, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Colorado, Eric R. Olson, Solicitor General, Robyn L. Wille, Senior Assistant Attorney General, Clare E. Connors, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Hawaii, William F. Cooper, Deputy Attorney General, Aaron M. Frey, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Maine, Laura E. Jensen, Assistant Attorney General, Brian E. Frosh, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Maryland, John B. Howard, Jr., Joshua M. Segal, and Steven J. Goldstein, Special Assistant Attorneys General, Maura Healey, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Melissa A. Hoffer and Christophe Courchesne, Assistant Attorneys General, Megan M. Herzog and David S. Frankel, Special Assistant Attorneys General, Dana Nessel, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Michigan, Gillian E. Wener, Assistant Attorney General, Keith Ellison, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Minnesota, Peter N. Surdo, Special Assistant Attorney General, Aaron D. Ford, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Nevada, Heidi Parry Stern, Solicitor General, Gurbir 11 S. Grewal, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of New Jersey, Lisa J. Morelli, Deputy Attorney General, Hector Balderas, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of New Mexico, Tania Maestas, Chief Deputy Attorney General, Joshua H. Stein, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of North Carolina, Asher Spiller, Assistant Attorney General, Ellen F. Rosenblum, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Oregon, Paul Garrahan, Attorney-in-Charge, Steve Novick, Special Assistant Attorney General, Josh Shapiro, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Ann R. Johnston, Senior Deputy Attorney General, Aimee D. Thomson, Deputy Attorney General, Peter F. Neronha, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Rhode Island, Gregory S. Schultz, Special Assistant Attorney General, Thomas J. Donovan, Jr., Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Vermont, Nicholas F. Persampieri, Assistant Attorney General, Mark Herring, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Virginia, Donald D. Anderson, Deputy Attorney General, Paul Kugelman, Jr., Senior Assistant Attorney General and Chief, Environmental Section, Caitlin Colleen Graham O=Dwyer, Assistant Attorney General, Robert W. Ferguson, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Washington, Christopher H. Reitz and Emily C. Nelson, Assistant Attorneys General, Karl A. Racine, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the District of Columbia, Loren L. AliKhan, Solicitor General, Tom Carr, City Attorney, Office of the City Attorney for the City of Boulder, Debra S. Kalish, Senior Counsel, Mark A. Flessner, Corporation Counsel, Office of the Corporation Counsel for the City of Chicago, Benna Ruth Solomon, Deputy Corporation Counsel, Jared Policicchio, Supervising Assistant Corporation Counsel, Kristin M. Bronson, City Attorney, Office of the City 12 Attorney for the City and County of Denver, Lindsay S. Carder and Edward J. Gorman, Assistant City Attorneys, Michael N. Feuer, City Attorney, Office of the City Attorney for the City of Los Angeles, Michael J. Bostrom, Assistant City Attorney, James E. Johnson, Corporation Counsel, New York City Law Department, Christopher G. King, Senior Counsel, Marcel S. Pratt, City Solicitor, City of Philadelphia Law Department, Scott J. Schwarz and Patrick K. O’Neill, Divisional Deputy City Solicitors, and Thomas F. Pepe, City Attorney, City of South Miami were on the brief for the State and Municipal Intervenors in support of respondents. Jeremiah Langston, Assistant Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Montana, Stephen C. Meredith, Solicitor, Office of the Attorney General for the Commonwealth of Kentucky, Margaret I. Olson, Assistant Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of North Dakota, and Erik E. Petersen, Assistant Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Wyoming, and Robert A. Wolf entered appearances. Patrick Morrisey, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of West Virginia, Lindsay S. See, Solicitor General, Thomas T. Lampman, Assistant Solicitor General, Scott A. Keller, Jeffrey H. Wood, Jeremy Evan Maltz, Steven P. Lehotsky, Michael B. Schon, Thomas A. Lorenzen, Elizabeth B. Dawson, Rae Cronmiller, Steve Marshall, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Alabama, Edmund G. LaCour, Jr., Solicitor General, Kevin G. Clarkson, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Alaska at the time the brief was filed, Clyde Sniffen, Jr., Attorney General, Leslie Rutledge, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Arkansas, Nicholas J. Bronni, Solicitor General, Vincent M. Wagner, Deputy Solicitor General, Dylan L. Jacobs, Assistant Solicitor General, Christopher M. Carr, Attorney General, 13 Office of the Attorney General for the State of Georgia, Andrew A. Pinson, Solicitor General, Derek Schmidt, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Kansas, Jeffrey A. Chanay, Chief Deputy Attorney General, Curtis T. Hill, Jr., Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General of Indiana, Thomas M. Fisher, Solicitor General, Andrew Beshear, Governor, Office of the Governor for the Commonwealth of Kentucky, S. Travis Mayo, Chief Deputy General Counsel, Taylor Payne, Deputy General Counsel, Joseph A. Newberg, Deputy General Counsel and Deputy Executive Director, Jeff Landry, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Louisiana, Elizabeth B. Murrill, Solicitor General, Harry J. Vorhoff, Assistant Attorney General, Eric S. Schmitt, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Missouri, D. John Sauer, Solicitor General, Julie Marie Blake, Deputy Solicitor General, Timothy C. Fox, Attorney General at the time the brief was filed, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Montana, Matthew T. Cochenour, Deputy Solicitor General, Wayne Stenehjem, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of North Dakota, Paul M. Seby, Special Assistant Attorney General, Douglas J. Peterson, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Nebraska, Justin D. Lavene, Assistant Attorney General, Dave Yost, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General of the State of Ohio, Benjamin M. Flowers, Solicitor General, Cameron F. Simmons, Principal Assistant Attorney General, Mike Hunter, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Oklahoma, Mithun Mansinghani, Solicitor General, Jason R. Ravnsborg, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of South Dakota, Steven R. Blair, Assistant Attorney General, Alan Wilson, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of South Carolina, James Emory Smith, Jr., Deputy Solicitor General, Ken Paxton, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for 14 the State of Texas, Kyle D. Hawkins, Solicitor General, Sean Reyes, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Utah, Tyler R. Green, Solicitor General, Bridget Hill, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of Wyoming, James Kaste, Deputy Attorney General, Todd E. Palmer, William D. Booth, Obianuju Okasi, Carroll W. McGuffey, III, Misha Tseytlin, C. Grady Moore, III, Julia Barber, F. William Brownell, Elbert Lin, Allison D. Wood, Emily Church Schilling, Kristina R. Van Bockern, David M. Flannery, Kathy G. Beckett, Edward L. Kropp, Amy M. Smith, Janet J. Henry, Melissa Horne, Angela Jean Levin, Eugene M. Trisko, John A. Rego, Reed W. Sirak, Michael A. Zody, Jacob Santini, Robert D. Cheren, Mark W. DeLaquil, and Andrew M. Grossman were on the brief for State and Industry Intervenors in support of respondents regarding Clean Power Plan Repeal. Wayne Stenehjem, Attorney General, Office of the Attorney General for the State of North Dakota, and Paul M. Seby, Special Assistant Attorney General, were on the brief for intervenor State of North Dakota in support of the respondents. Jerry Stouck entered an appearance. Thomas J. Ward, Megan H. Berge, and Jared R. Wigginton were on the brief for amicus curiae National Association of Builders in support of respondents. Before: MILLETT , PILLARD , and WALKER, Circuit Judges. Opinion for the Court filed PER CURIAM. Opinion concurring in part, concurring in the judgment in part, and dissenting in part filed by Circuit Judge WALKER. 15 TABLE OF C ONTENTS I. Background .........................................................................17 A. The Clean Air Act ..........................................................17 B. Electricity and Climate Change .....................................21 1. Electricity.....................................................................21 2. Climate Change and the Federal Government ..........24 C. The Clean Power Plan ....................................................29 D. The ACE Rule ................................................................32 1. Repeal of the Clean Power Plan .................................32 2. Best System of Emission Reduction ..........................33 3. Degree of Emission Limitation Achievable ..............36 4. Implementing Regulations..........................................38 E. Petitions for Review .......................................................38 F. Jurisdiction and Standard of Review .............................39 II. Section 7411 .......................................................................40 A. Statutory Context............................................................40 1. Text ..............................................................................46 2. Statutory History, Structure, and Purpose .................59 3. Compliance Measures .................................................71 B. The Major Questions Doctrine ......................................74 1. The EPA’s Regulatory Mandate ................................75 2. Best System of Emission Reduction ..........................80 C. Federalism .......................................................................92 III. The EPA’s Authority to Regulate Carbon Dioxide Emissions Under Section 7411 ..............................................98 A. The Coal Petitioners’ Challenges ..................................98 1. Endangerment Finding................................................99 2. Section 7411 and Section 7412’s Parallel Operation...................................................... 111 B. The Robinson Petitioners’ Challenges ....................... 132 IV. Amendments to the Implementing Regulations ...... 138 V. Vacatur and Remand .................................................... 146 VI. Conclusion ..................................................................... 147 16 As the Supreme Court recognized nearly fourteen years ago, climate change has been called “the most pressing environmental challenge of our time.” Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. 497, 505 (2007) (formatting modified). Soon thereafter, the United States government determined that greenhouse gas emissions are polluting our atmosphere and causing significant and harmful effects on the human environment. Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings for Greenhouse Gases Under Section 202(a) of the Clean Air Act (2009 Endangerment Finding), 74 Fed. Reg. 66,496, 66,497–66,499 (Dec. 15, 2009). And both Republican and Democratic administrations have agreed: Power plants burning fossil fuels like coal “are far and away” the largest stationary source of greenhouse gases and, indeed, their role in greenhouse gas emissions “dwarf[s] other categories[.]” EPA Br. 169; see also Standards of Performance for Greenhouse Gas Emissions from New, Modified, and Reconstructed Stationary Sources: Electric Utility Generating Units (New Source Rule), 80 Fed. Reg. 64,510, 64,522 (Oct. 23, 2015) (fossil-fuel-fired power plants are “by far the largest emitters” of greenhouse gases). The question in this case is whether the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) acted lawfully in adopting the 2019 Affordable Clean Energy Rule (ACE Rule), 84 Fed. Reg. 32,520 (July 8, 2019), as a means of regulating power plants’ emissions of greenhouse gases. It did not. Although the EPA has the legal authority to adopt rules regulating those emissions, the central operative terms of the ACE Rule and the repeal of its predecessor rule, the Clean Power Plan, 80 Fed. Reg. 64,662 (Oct. 23, 2015), hinged on a fundamental misconstruction of Section 7411(d) of the Clean Air Act. In addition, the ACE Rule’s amendment of the regulatory framework to slow the process for reduction of emissions is arbitrary and capricious. For those reasons, the ACE Rule is 17 vacated, and the record is remanded to the EPA for further proceedings consistent with this opinion. I. BACKGROUND A. T HE C LEAN AIR ACT In 1963, Congress passed the Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7401 et seq., “to protect and enhance the quality of the Nation’s air resources so as to promote the public health and welfare and the productive capacity of its population[,]” id. § 7401(b)(1). Animating the Act was Congress’ finding that “growth in the amount and complexity of air pollution brought about by urbanization, industrial development, and the increasing use of motor vehicles[] has resulted in mounting dangers to the public health and welfare[.]” Id. § 7401(a)(2). Section 111 of the Clean Air Act, which was added in 1970 and codified at 42 U.S.C. § 7411, directs the EPA to regulate any new and existing stationary sources of air pollutants that “cause[], or contribute[] significantly to, air pollution” and that “may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.” 42 U.S.C. § 7411(b)(1)(A); see id. § 7411(d), (f) (providing that the EPA Administrator “shall” regulate existing and new sources of air pollution). A “stationary source” is a source of air pollution that cannot move, such as a power plant. See id. § 7411(a)(3) (defining “stationary source” as “any building, structure, facility, or installation which emits or may emit any air pollutant[]”). An example of a common nonstationary source of air pollution is a gas-powered motor vehicle. See Utility Air Regulatory Group v. EPA (UARG), 573 U.S. 302, 308 (2014). Within 90 days of the enactment of Section 7411, the EPA Administrator was to promulgate a list of stationary source categories that “cause[], or contribute[] significantly to, air 18 pollution[.]” 42 U.S.C. § 7411(b)(1)(A). In 1971, the Administrator included fossil-fuel-fired steam-generating power plants on that list. Air Pollution Prevention and Control: List of Categories of Stationary Sources, 36 Fed. Reg. 5,931 (March 31, 1971); see also New Source Rule, 80 Fed. Reg. at 64,527–64,528. Today’s power plants fall in that same category. ACE Rule, 84 Fed. Reg. at 32,557 n.250. Once a stationary source category is listed, the Administrator must promulgate federal “standards of performance” for all newly constructed sources in the category. 42 U.S.C. § 7411(b)(1)(B). The Act defines a “standard of performance” as a standard for emissions of air pollutants which reflects the degree of emission limitation achievable through the application of the best system of emission reduction which (taking into account the cost of achieving such reduction and any nonair quality health and environmental impact and energy requirements) the Administrator determines has been adequately demonstrated. Id. § 7411(a)(1). Once such a new source regulation is promulgated, the Administrator also must issue emission guidelines for alreadyexisting stationary sources within that same source category. 42 U.S.C. § 7411(d)(1)(A)(ii); see also American Elec. Power Co., Inc. v. Connecticut (AEP), 564 U.S. 410, 424 (2011). While the new source standards are promulgated and enforced entirely by the EPA, the Clean Air Act prescribes a process of cooperative federalism for the regulation of existing sources. Under that structure, the statute delineates three distinct regulatory steps involving three sets of actors—the 19 EPA, the States, and regulated industry—each of which has a flexible role in choosing how to comply. See 42 U.S.C. § 7411(a)(1), (d). This allows each State to work with the stationary sources within its jurisdiction to devise a plan for meeting the federally promulgated quantitative guideline for emissions. See id. § 7411(d). The process starts with the EPA first applying its expertise to determine “the degree of emission limitation achievable through the application of the best system of emission reduction” that “has been adequately demonstrated.” 42 U.S.C. § 7411(a)(1); see 40 C.F.R. § 60.22a. That system must “tak[e] into account the cost of achieving such reduction and any nonair quality health and environmental impact and energy requirements[.]” 42 U.S.C. § 7411(a)(1). Once the Administrator identifies the best system of emission reduction, she then determines the amount of emission reduction that existing sources should be able to achieve based on the application of that system and adopts corresponding emission guidelines. Id.; see also, e.g., ACE Rule, 84 Fed. Reg. at 32,523; Clean Power Plan, 80 Fed. Reg. at 64,719. Each State then submits to the EPA a plan that (i) establishes standards of performance for that State’s existing stationary sources’ air pollutants (excepting pollutants already subject to separate federal emissions standards), and (ii) “provides for the implementation and enforcement of such standards of performance[]” by the State. 42 U.S.C. § 7411(d)(1); see 40 C.F.R. § 60.23a. The standards of performance must “reflect[]” the emission targets that the EPA has determined are achievable. 42 U.S.C. § 7411(a)(1). In this context, a state standard need not adopt the best system identified by the EPA to “reflect[]” it. Id.; see 40 C.F.R. § 60.24a(c). Instead, the Clean Air Act affords States significant flexibility in designing and enforcing standards that 20 employ other approaches so long as they meet the emission guidelines prescribed by the Agency. If a State fails to submit a satisfactory plan, the EPA may prescribe a plan for that State. 42 U.S.C. § 7411(d)(2)(A); see 40 C.F.R. § 60.27a(c)-(e). Similarly, if the State submits a plan but fails to enforce it, the EPA itself may enforce the plan’s terms. Id. § 7411(d)(2)(B). The third and final set of relevant actors are the regulated entities themselves, to which, under the Act, the States may afford leeway in crafting compliance measures. See Clean Power Plan, 80 Fed. Reg. at 64,666; ACE Rule, 84 Fed. Reg. at 32,555. The EPA has exercised its authority under Section 7411 over the years to set emission limitations for different types of air pollution from various categories of existing sources. See 42 Fed. Reg. 12,022 (March 1, 1977) (fluorides from phosphate fertilizer plants); 42 Fed. Reg. 55,796 (Oct. 18, 1977) (acid mist from sulfuric acid plants); 44 Fed. Reg. 29,828 (May 22, 1979) (total reduced sulfur from kraft pulp plants); 45 Fed. Reg. 26,294 (April 17, 1980) (fluorides from primary aluminum plants); 60 Fed. Reg. 65,387 (Dec. 19, 1995) (various pollutants from municipal waste combustors); 61 Fed. Reg. 9905 (March 12, 1996) (landfill gases from municipal solid waste landfills); 70 Fed. Reg. 28,606 (May 18, 2005) (mercury from coal-fired power plants). The Clean Air Act is a comprehensive statute that includes a variety of regulatory programs for tackling air pollution in addition to Section 7411. Regulated parties may be subject to one or more programs. As relevant here, the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) provisions, 42 U.S.C. §§ 7408–7410, govern the levels of specified air pollutants that may be present in the atmosphere to protect air quality and the 21 public health and welfare. The Hazardous Air Pollutants program, id. § 7412, directs the EPA to establish strict emission limitations for the most dangerous air pollutants emitted from major sources. Section 7411’s cooperative federalism program for existing sources operates as a gap-filler, requiring the EPA to regulate harmful emissions not controlled under those other two programs. Id. § 7411(d)(1)(i). B. E LECTRICITY AND CLIMATE CHANGE 1. Electricity Electricity powers the world. Chances are that you are reading this opinion on a device that consumes electricity. Yet two distinct characteristics of electricity make its production and delivery in the massive quantities demanded by consumers an exceptionally complex process. First, unlike most products, electricity is a perfectly fungible commodity. Grid Experts Amicus Br. 6. A watt of electricity is a watt of electricity, no matter who makes it, how they make it, or where it is purchased. Second, at least as of now, this highly demanded product cannot be effectively stored at scale after it is created. Paul L. Joskow, Creating a Smarter U.S. Electricity Grid, 26 J. ECON. PERSP. 29, 31–33 (2012).1 Instead, electricity must 1 Change in storage capacity is picking up speed. See generally Richard L. Revesz & Burcin Unel, Managing the Future of the Electricity Grid: Energy Storage and Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 42 HARV. ENV’T L. REV. 139, 140–141 (2018) (describing ongoing declines in cost of storage); LAZARD, LAZARD’S LEVELIZED COST OF STORAGE ANALYSIS—VERSION 6.0 (2020) (noting “storage costs have declined across most use cases and technologies, particularly for shorter-duration applications, in part driven by evolving preferences in the industry”). Nevertheless, the grid’s production capacity still far exceeds its present storage capacity. Univ. of Mich. 22 constantly be produced, and is almost instantaneously consumed. See Clean Power Plan, 80 Fed. Reg. at 64,677, 64,692; Grid Experts Amicus Br. 8. Those unique attributes led to the creation of the American electrical grid. 2 The grid has been called the “supreme engineering achievement of the 20th century,” MASS. INST. OF TECH., THE FUTURE OF THE ELECTRIC GRID 1 (2011) (formatting modified), and it is an exceptionally complex, interconnected system. “[A]ny electricity that enters the grid immediately becomes a part of a vast pool of energy that is constantly moving[.]” New York v. FERC, 535 U.S. 1, 7 (2002). That means that units of electricity as delivered to the user are identical, no matter their source. On the grid, there is no coal-generated electricity or renewable-generated electricity; there is just electricity. See Clean Power Plan, 80 Fed. Reg. at 64,692; Grid Experts Amicus Br. 7–8. Also, because storing electricity for any length of time remains technically challenging and often costly, the components of the grid must operate as a perfectly calibrated machine to deliver the amount of electricity that all consumers across the United States need at the moment they need it. Grid Experts Amicus Ctr. for Sustainable Sys., U.S. GRID ENERGY STORAGE (Sept. 2020), http://css.umich.edu/sites/default/files/US%20Grid%20Energy%20 Storage_CSS15-17_e2020.pdf (last visited Jan. 11, 2021) (United States has 1,100 gigawatts of installed generation capacity and just 23 gigawatts of storage capacity). 2 Technically, “grids.” There are three regional grids in the contiguous United States: Eastern, Western, and Texas. Grid Experts Amicus Br. 9; see also United States Dep’t of Energy, North American Electric Reliability Corporation Interconnections, https://www.energy.gov/oe/downloads/north-american-electricreliability-corporation-interconnections (last visited Jan. 11, 2021). 23 Br. 8, 10–11; see also 80 Fed. Reg. at 64,677. “If [someone] in Atlanta on the Georgia [leg of the] system turns on a light, every generator on Florida’s system almost instantly is caused to produce some quantity of additional electric energy which serves to maintain the balance in the interconnected system[.]” Federal Power Comm’n v. Florida Power & Light Co., 404 U.S. 453, 460 (1972) (citation omitted). “Like orchestra conductors signaling entrances and cut-offs, grid operators use automated systems to signal particular generators to dispatch more or less power to the grid as needed over the course of the day, thus ensuring that power pooled on the grid rises and falls to meet changing demand.” Grid Experts Amicus Br. 11. Most generators of electricity on the American grid create power by burning fossil fuels like coal, oil, and natural gas. See United States Energy Information Administration (EIA), Frequently Asked Questions: What Is U.S. Electricity Generation by Energy Source? (Nov. 2, 2020), https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=427&t=3 (last visited Jan. 11, 2021) (fossil fuels represented 62.6 percent of electricity generation in 2019). Some of those power plants take a fossil fuel (usually coal) and burn it in a water boiler to make steam. Other power plants take a different fossil fuel (usually natural gas), mix it with highly compressed air, and ignite it to release a combination of super-hot gases. Either way, that steam or superheated mixture is piped into giant turbines that catch the gases and rotate at extreme speeds. Those turbines turn generators, which spin magnets within wire coils to produce electricity. EIA, Electricity Explained (Nov. 9, 2020), https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/ electricity/how-electricity-is-generated.php (last visited Jan 11, 2021). 24 2. Climate Change and the Federal Government Electrical power has become virtually as indispensable to modern life as air itself. But electricity generation has come into conflict with air quality in ways that threaten human health and well-being when power generated by burning fossil fuels emits carbon dioxide and other polluting greenhouse gases into the air. Since the late 1970s, the federal government has focused “serious attention” on the effects of carbon dioxide pollution on the climate. Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. at 507. In 1978, Congress adopted the National Climate Program Act, Pub. L. No. 95-367, 92 Stat. 601, which directed the President to study and devise an appropriate response to “man-induced climate processes and their implications[,]” id. § 3; see Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. at 507–508. In response, the National Academy of Sciences’ National Research Council reported “no reason to doubt that climate changes will result” if “carbon dioxide continues to increase,” and “[a] wait-andsee policy may mean waiting until it is too late.” Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. at 508 (quoting CLIMATE RESEARCH BOARD , CARBON D IOXIDE & CLIMATE: A SCIENTIFIC ASSESSMENT, at viii (1979)). In 1987, Congress passed the Global Climate Protection Act, which found that “manmade pollution[,]” including “the release of carbon dioxide, * * * may be producing a long-term and substantial increase in the average temperature on Earth[.]” Pub. L. No. 100-204, Title XI, §1102(1), 101 Stat. 1407, 1408 (codified at 15 U.S.C. § 2901 note). The Climate Protection Act directed the EPA to formulate a “coordinated national policy on global climate change.” Id. § 1103(b), 101 Stat. at 1408; see Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. at 508. 25 It was not until the Supreme Court’s 2007 decision in Massachusetts v. EPA, however, that the Court confirmed that carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions constituted “air pollutant[s]” covered by the Clean Air Act. See 549 U.S. at 528. The Supreme Court explained that the Clean Air Act’s “sweeping definition of ‘air pollutant’ includes ‘any air pollution agent or combination of such agents, including any physical, chemical . . . substance or matter which is emitted into or otherwise enters the ambient air[.]’” Id. at 528–529 (quoting 42 U.S.C. § 7602(g)). The Act, the Supreme Court held, “is unambiguous” in that regard. Id. at 529. “On its face, the definition embraces all airborne compounds of whatever stripe, and underscores that intent through the repeated use of the word ‘any.’” Id. And “[c]arbon dioxide” and other common greenhouse gases are “without a doubt” chemical substances that are “emitted into . . . the ambient air.” Id. (quoting 42 U.S.C. § 7602(g)). Given that statutory command, the Supreme Court ruled that the EPA “can avoid taking further action” to regulate such pollution “only if it determines that greenhouse gases do not contribute to climate change” or offers some reasonable explanation for not resolving that question. Massachusetts v. EPA, 549 U.S. at 533. Taking up the mantle, the EPA in 2009 found “compelling[]” evidence that emissions of greenhouse gases are polluting the atmosphere and are endangering human health and welfare by causing significant damage to the environment. 2009 Endangerment Finding, 74 Fed. Reg. at 66,497; see id. (“[T]he Administrator finds that greenhouse gases in

8613371530291

8613371530291