rongsheng refinery capacity pricelist

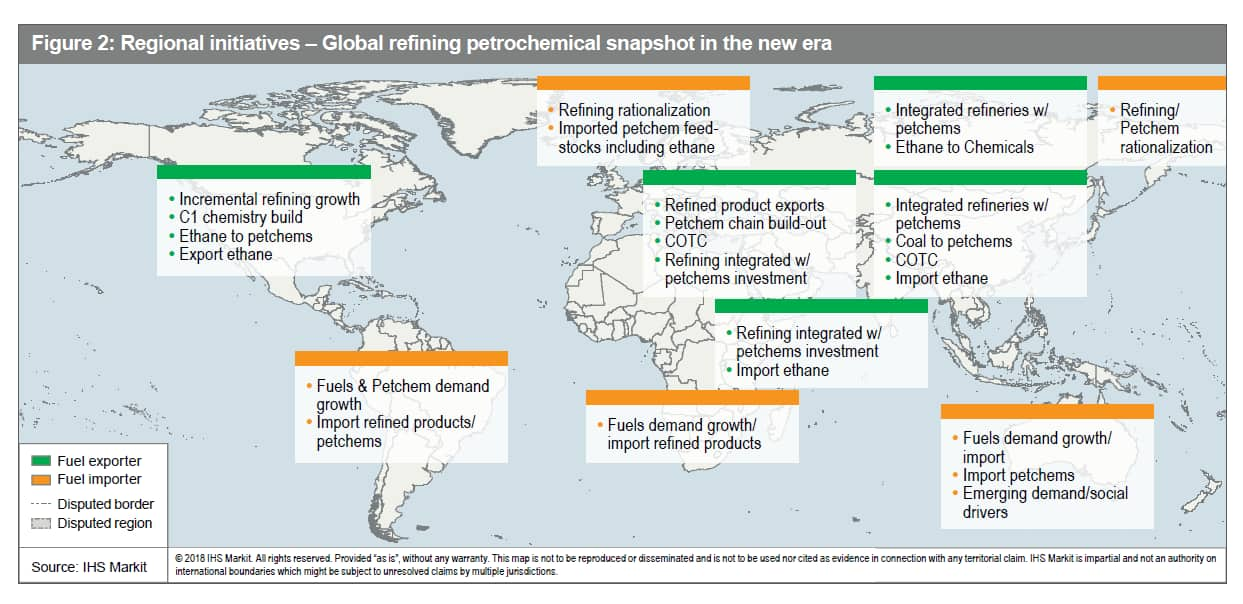

In Asia and the Middle East, at least nine refinery projects are beginning operations or are scheduled to come online before the end of 2023. At their current planned capacities, they will add 2.9 million barrels per day (b/d) of global refinery capacity once fully operational.

In the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) June 2022 Oil Market Report, the IEA expects net global refining capacity to expand by 1.0 million b/d in 2022 and by an additional 1.6 million b/d in 2023. Net capacity additions reflect total new capacity minus capacity that has closed.

The scheduled expansions follow a period of reduced global refining capacity. Net global capacity declined in 2021 for the first time in 30 years, according to the IEA. The new refinery projects would increase production of refined products, such as gasoline and diesel, and in turn, they might reduce the current high prices for these products.

China’s refinery capacity is scheduled to increase significantly this year. The Shenghong Petrochemical facility in Lianyungang has an estimated capacity of 320,000 b/d, and they report that trial crude oil-processing operations began in May 2022. In addition, PetroChina’s 400,000 b/d Jieyang refinery is expected to come online in the third quarter of 2022. A planned 400,000 b/d Phase II capacity expansion also began operations earlier this year at Zhejiang Petrochemical Corporation’s (ZPC) Rongsheng facility. More information on these expansions is available in our Country Analysis Executive Summary: China.

Outside of China, the 300,000 b/d Malaysian Pengerang refinery (also known as the RAPID refinery) restarted in May 2022 after a fire forced the refinery to shut down in March 2020. In India, the Visakha Refinery is undergoing a major expansion, scheduled to add 135,000 b/d by 2023.

New projects in the Middle East are also likely to be an important source of new refining capacity. The 400,000 b/d Jizan refinery in Saudi Arabia reportedly came online in late 2021 and began exporting petroleum products earlier this year. More recently, the 615,000 b/d Al Zour refinery in Kuwait—the largest in the country when it becomes fully operational—began initial operations earlier this year. A new 140,000 b/d refinery is scheduled to come online in Karbala, Iraq, this September, targeting fully operational status by 2023. A new 230,000 b/d refinery is set to come online in Duqm, Oman, likely in early 2023.

These estimates do not necessarily include all ongoing refinery capacity expansions. Moreover, many of these projects have already been subject to major delays, and the possibility of partial starts or continued delays related to logistics, construction, labor, finances, political complications, or other factors may cause these projects to come online later than estimated. Although the potential for project complications and cancellations is always a significant risk, these projects could otherwise account for an increase of nearly 3.0 million b/d of new refining capacity by the end of 2023.

China"s private refiner Zhejiang Petroleum & Chemical is set to start trial runs at its second 200,000 b/d crude distillation unit at the 400,000 b/d phase 2 refinery by the end of March, a source with close knowledge about the matter told S&P Global Platts March 9.

"The company targets to commence the phase II project this year, and run both the two phases at above 100% of their capacity, which will lift crude demand in 2021," the source said.

ZPC cracked 23 million mt of crude in 2020, according the the source. Platts data showed that the utilization rate of its phase 1 refinery hit as high as 130% in a few months last year.

Started construction in the second half of 2019, units of the Yuan 82.9 billion ($12.74 billion) phase 2 refinery almost mirror those in phase 1, which has two CDUs of 200,000 b/d each. But phase 1 has one 1.4 million mt/year ethylene unit while phase 2 plans to double the capacity with two ethylene units.

ZPC currently holds about 6 million cu m (37.74 million barrels) in crude storage tanks, equivalent to 47 days of the two plants" consumption if they run at 100% capacity.

With the entire phase 2 project online, ZPC expects to lift its combined petrochemicals product yield to 71% from 65% for the phase 1 refinery, according to the source.

Zhejiang Petroleum, a joint venture between ZPC"s parent company Rongsheng Petrochemical and Zhejiang Energy Group, planned to build 700 gas stations in Zhejiang province by end-2022 as domestic retail outlets of ZPC.

Established in 2015, ZPC is a JV between textile companies Rongsheng Petrochemical, which owns 51%, Tongkun Group, at 20%, as well as chemicals company Juhua Group, also 20%. The rest 9% stake was reported to have transferred to Saudi Aramco from the Zhejiang provincial government. But there has been no update since the agreement was signed in October 2018.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that global refining capacity decreased by 730,000 barrels per day (b/d) in 2021—the first decline in global refining capacity in 30 years.

In the United States, refining capacity has decreased by about 1.1 million b/d since the start of 2020, contributing 184,000 b/d to the global decline in 2021. Global demand for refined products dropped substantially in 2020 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Less petroleum demand and the associated lower petroleum product prices encouraged refinery closures, reducing global refining capacity, particularly in the United States, Europe, and Japan. However, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) notes that a number of new refinery projects are set to come online during 2022 and 2023, increasing capacity.

As global demand for petroleum products returned closer to pre-pandemic levels through 2021 and early 2022, the loss of refinery capacity contributed to higher crack spreads—the difference between the price of a barrel of crude oil and the wholesale price of petroleum products—which serve as one indicator of the profitability of refining.

Associated sanctions on Russia—with more than 5 million b/d in crude oil processing capacity—disrupted exports of Russia’s refined products into the global market, and will likely continue to do so as import bans in the European Union and United Kingdom come into full force.

Constraints on global refinery capacity have been contributing to higher crack spreads in the first half of 2022, and they are likely to continue contributing to high crack spreads through at least the end of this year.

In its June 2022 Oil Market Report, the IEA expects net global refining capacity to expand by 1.0 million b/d in 2022 and by an additional 1.6 million b/d in 2023. New refining capacity growth includes several high-profile, high-capacity refinery projects underway, particularly in China and the Middle East, which could add more than 4.0 million b/d of new capacity over the next two years.

High-capacity refineries require access to reliable sources of crude oil inputs to maintain higher utilization and to a sufficiently large pool of potential customers to supply. Many of these new refineries are located in coastal areas and have easy access to export refined products that are not consumed domestically.

The most global refining capacity under development is in China. Chinese capacity is scheduled to increase significantly this year because of the start of at least two new refinery projects and a major refinery expansion.

The first new refinery is the private Shenghong Petrochemical facility in Lianyungang, which has an estimated capacity of 320,000 b/d and reported trial crude oil-processing operations beginning in May 2022.

The second new refinery is PetroChina’s 400,000 b/d Jieyang refinery, in the southern Guangdong province, which is expected to come online in the third quarter of 2022 (3Q22). A planned 400,000 b/d Phase II capacity expansion also began operations earlier in 2022 at Zhejiang Petrochemical Corporation’s (ZPC) Rongsheng facility.

Although these projects are the most imminent new capacity expansions in China, the country is expected to continue increasing its refining and petrochemical processing capacity through a number of additional projects expected to come online by 2030.

Most noteworthy among these additional expansions are the 300,000 b/d Huajin and the 400,000 b/d Yulong refinery projects, which both have target start dates in 2024.

Outside of China, the 300,000 b/d Malaysian Pengerang refinery restarted in May 2022 after a fire forced the refinery to shut down in March 2020. The refinery’s return is likely to decrease petroleum product prices and increase supply, particularly in south and southeast Asian markets.

Substantial refinery capacity was also added in the Middle East during the past year. The 400,000 b/d Jizan refinery in Saudi Arabia reportedly came online in late 2021 and began exporting petroleum products earlier this year.

More recently, the 615,000 b/d Al Zour refinery in Kuwait—the largest in the country when it becomes fully operational—began initial operations earlier this year and the facility’s operators expect to increase production through the end of 2022.

A new 140,000 b/d refinery is scheduled to come online in Karbala, Iraq, this September, targeting to be fully operational by 2023. A new 230,000 b/d refinery operated by a joint venture between state-owned-firms OQ (of Oman) and Kuwait Petroleum International is set to come online in Duqm, Oman, likely in early 2023.

More than 2 million b/d of new refining capacity construction is expected to come online to support markets in the Indian Ocean basin in 2022. At the same time, a handful of major projects are also planned in the Atlantic basin.

The 650,000 b/d Dangote Industries refinery in Lagos, Nigeria, set to be the largest in the country when completed, may come online in late 2022 or 2023. The refinery would most likely meet Nigeria’s domestic petroleum product demand as well as demand in nearby African countries, and it would also reduce demand for gasoline and diesel imports into the region from Europe or the United States.

In Mexico, state-owned refiner Pemex has been building a 340,000 b/d refinery in Dos Bocas, which hosted an inauguration ceremony on 1 July, even though the refinery is still under construction and is unlikely to begin producing fuels until at least 2023.

TotalEnergies is planning to restart its 222,000 b/d Donges refinery along the Atlantic Coast of France in May 2022, after closing the facility in late 2020, and some reports indicate the facility has begun importing crude oil for processing.

In addition to major new refinery projects, other facilities are also moving forward with capacity expansions at existing refineries—particularly in India. HPCL’s Visakha Refinery is undergoing a major expansion, estimated at 135,000 b/d, which is scheduled to come online by 2023. A number of other similar expansions are underway in India that may come into effect in 2024 or later.

Although no projects to build new refineries in the United States are currently planned, major refinery expansions are underway at a handful of Gulf Coast refineries, most notably ExxonMobil’s Beaumont, Texas refinery, which plans to increase its capacity by 250,000 b/d by 2023.

Facilities along the Gulf Coast currently account for 54% of all US domestic refining capacity. They supply fuels for US domestic petroleum consumption, but they are also substantial exporters into the Atlantic basin market, particularly into Central and South America and also into Europe.

If the projects mentioned above were to come online according to their present timelines, global refinery capacity would increase by 2.3 million b/d in 2022 and by 2.1 million b/d in 2023.

EIA cautions that the estimate is not necessarily a complete list of ongoing refinery capacity expansions. Moreover, many of these projects have also already been subject to major delays, and the possibility of partial starts or continued delays related to logistics, construction, labor, finances, political complications, or other factors may cause these projects to come online later than currently estimated.

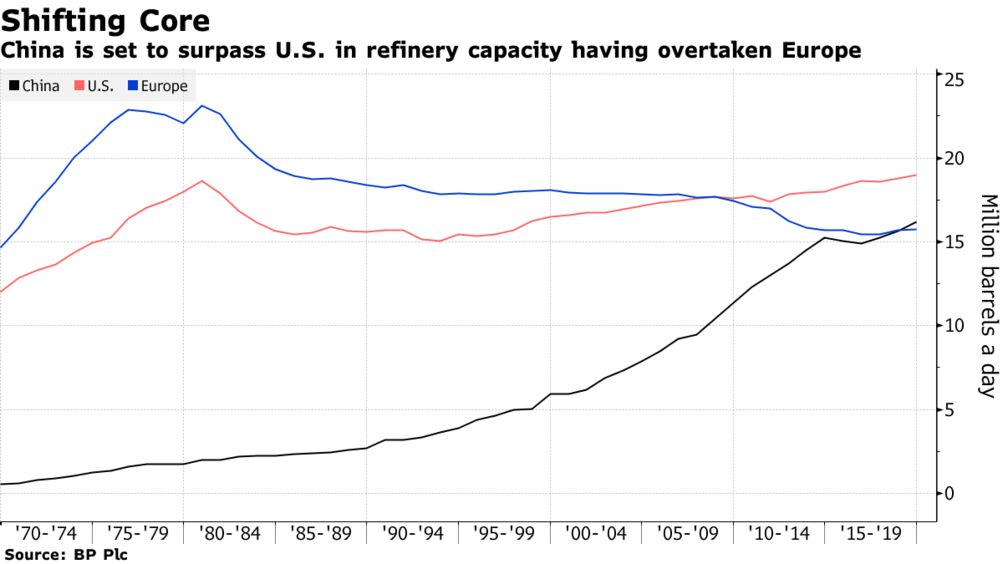

This year, China is expected to overtake the United States as the world’s largest oil refining country.[1] Although China’s bloated and fragmented crude oil refining sector has undergone major changes over the past decade, it remains saddled with overcapacity.[2]

Privately owned unaffiliated refineries, known as “teapots,”[3] mainly clustered in Shandong province, have been at the center of Beijing’s longtime struggle to rein in surplus refining capacity and, more recently, to cut carbon emissions. A year ago, Beijing launched its latest attempt to shutter outdated and inefficient teapots — an effort that coincides with the emergence of a new generation of independent players that are building and operating fully integrated mega-petrochemical complexes.[4]

China’s “teapot” refineries[5] play a significant role in refining oil and account for a fifth of Chinese crude imports.[6] Historically, teapots conducted most of their business with China’s major state-owned companies, buying crude oil from and selling much of their output to them after processing it into gasoline and diesel. Though operating in the shadows of China’s giant national oil companies (NOCs),[7] teapots served as valuable swing producers — their surplus capacity called on in times of tight markets.

Four years later, the NDRC adopted a different approach, awarding licenses and quotas to teapot refiners to import crude oil and granting approval to export refined products in exchange for reducing excess capacity, either upgrading or removing outdated facilities, and building oil storage facilities.[10] But this partial liberalization of the refining sector did not go exactly according to plan. Swelling with new sources of feedstock that catapulted China into the position of the world’s largest oil importer, teapots increased their production of refined fuels and, benefiting from greater processing flexibility and low labor costs undercut larger state rivals and doubled their market share.[11]

Meanwhile, as teapots expanded their operations, they took on massive debt, flouted environmental rules, and exploited taxation loopholes.[12] Of the refineries that managed to meet targets to cut capacity, some did so by double counting or reporting reductions in units that had been idled.[13] And when, reversing course, Beijing revoked the export quotas allotted to teapots and mandated that products be sold via state-owned companies, it trapped their output in China, contributing to the domestic fuel glut.

2021 marked the start of the central government’s latest effort to consolidate and tighten supervision over the refining sector and to cap China’s overall refining capacity.[14] Besides imposing a hefty tax on imports of blending fuels, Beijing has instituted stricter tax and environmental enforcement[15] measures including: performing refinery audits and inspections;[16] conducting investigations of alleged irregular activities such as tax evasion and illegal resale of crude oil imports;[17] and imposing tighter quotas for oil product exports as China’s decarbonization efforts advance.[18]

The politics surrounding this new class of greenfield mega-refineries is important, as is their geographical distribution. Beijing’s reform strategy is focused on reducing the country’s petrochemical imports and growing its high value-added chemical business while capping crude processing capacity. The push by Beijing in this direction has been conducive to the development of privately-led mega refining and petrochemical projects, which local officials have welcomed and staunchly supported.[20]

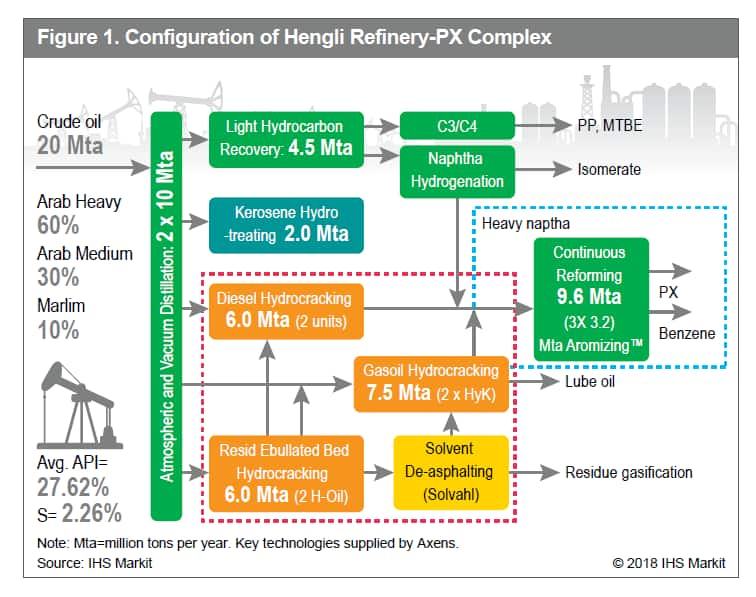

Yet, of the three most recent major additions to China’s greenfield refinery landscape, none are in Shandong province, home to a little over half the country’s independent refining capacity. Hengli’s Changxing integrated petrochemical complex is situated in Liaoning, Zhejiang’s (ZPC) Zhoushan facility in Zhejiang, and Shenghong’s Lianyungang plant in Jiangsu.[21]

As China’s independent oil refining hub, Shandong is the bellwether for the rationalization of the country’s refinery sector. Over the years, Shandong’s teapots benefited from favorable policies such as access to cheap land and support from a local government that grew reliant on the industry for jobs and contributions to economic growth.[22] For this reason, Shandong officials had resisted strictly implementing Beijing’s directives to cull teapot refiners and turned a blind eye to practices that ensured their survival.

But with the start-up of advanced liquids-to-chemicals complexes in neighboring provinces, Shandong’s competitiveness has diminished.[23] And with pressure mounting to find new drivers for the provincial economy, Shandong officials have put in play a plan aimed at shuttering smaller capacity plants and thus clearing the way for a large-scale private sector-led refining and petrochemical complex on Yulong Island, whose construction is well underway.[24] They have also been developing compensation and worker relocation packages to cushion the impact of planned plant closures, while obtaining letters of guarantee from independent refiners pledging that they will neither resell their crude import quotas nor try to purchase such allocations.[25]

To be sure, the number of Shandong’s independent refiners is shrinking and their composition within the province and across the country is changing — with some smaller-scale units facing closure and others (e.g., Shandong Haike Group, Shandong Shouguang Luqing Petrochemical Corp, and Shandong Chambroad Group) pursuing efforts to diversify their sources of revenue by moving up the value chain. But make no mistake: China’s teapots still account for a third of China’s total refining capacity and a fifth of the country’s crude oil imports. They continue to employ creative defensive measures in the face of government and market pressures, have partnered with state-owned companies, and are deeply integrated with crucial industries downstream.[26] They are consummate survivors in a key sector that continues to evolve — and they remain too important to be driven out of the domestic market or allowed to fail.

In 2016, during the period of frenzied post-licensing crude oil importing by Chinese independents, Saudi Arabia began targeting teapots on the spot market, as did Kuwait. Iran also joined the fray, with the National Iranian Oil Company (NIOC) operating through an independent trader Trafigura to sell cargoes to Chinese independents.[27] Since then, the coming online of major new greenfield refineries such as Rongsheng ZPC and Hengli Changxing, and Shenghong, which are designed to operate using medium-sour crude, have led Middle East producers to pursue long-term supply contracts with private Chinese refiners. In 2021, the combined share of crude shipments from Saudi Arabia, UAE, Oman, and Kuwait to China’s independent refiners accounted for 32.5%, an increase of more than 8% over the previous year.[28] This is a trend that Beijing seems intent on supporting, as some bigger, more sophisticated private refiners whose business strategy aligns with President Xi’s vision have started to receive tax benefits or permissions to import larger volumes of crude directly from major producers such as Saudi Arabia.[29]

The shift in Saudi Aramco’s market strategy to focus on customer diversification has paid off in the form of valuable supply relationships with Chinese independents. And Aramco’s efforts to expand its presence in the Chinese refining market and lock in demand have dovetailed neatly with the development of China’s new greenfield refineries.[30] Over the past several years, Aramco has collaborated with both state-owned and independent refiners to develop integrated liquids-to-chemicals complexes in China. In 2018, following on the heels of an oil supply agreement, Aramco purchased a 9% stake in ZPC’s Zhoushan integrated refinery. In March of this year, Saudi Aramco and its joint venture partners, NORINCO Group and Panjin Sincen, made a final investment decision (FID) to develop a major liquids-to-chemicals facility in northeast China.[31] Also in March, Aramco and state-owned Sinopec agreed to conduct a feasibility study aimed at assessing capacity expansion of the Fujian Refining and Petrochemical Co. Ltd.’s integrated refining and chemical production complex.[32]

BEIJING, Aug 14 (Reuters) - Rongsheng Petrochemical , the listed arm of a major shareholder in one of China’s biggest private oil refineries, expects demand for energy and chemical products to return to normal in the country in the second half of this year.

Rongsheng expects to start trial operations of the second phase of the refining project, adding another 400,000 bpd of refining capacity and 1.4 million tonnes of ethylene production capacity in the fourth quarter of 2020.

“We expect the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on energy and chemicals to have basically faded in spite of the possibility of new waves of outbreak,” said Quan Weiying, board secretary of Rongsheng, in response to Reuters questions in an online briefing.

But Li Shuirong, president of Rongsheng, told the briefing that it was still in the process of applying for an export quota and would adjust production based on market demand. (Reporting by Muyu Xu and Chen Aizhu; Editing by Jacqueline Wong)

Saudi Aramco today signed three Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) aimed at expanding its downstream presence in the Zhejiang province, one of the most developed regions in China. The company aims to acquire a 9% stake in Zhejiang Petrochemical’s 800,000 barrels per day integrated refinery and petrochemical complex, located in the city of Zhoushan.

The first agreement was signed with the Zhoushan government to acquire its 9% stake in the project. The second agreement was signed with Rongsheng Petrochemical, Juhua Group, and Tongkun Group, who are the other shareholders of Zhejiang Petrochemical. Saudi Aramco’s involvement in the project will come with a long-term crude supply agreement and the ability to utilize Zhejiang Petrochemical’s large crude oil storage facility to serve its customers in the Asian region.

Phase I of the project will include a newly built 400,000 barrels per day refinery with a 1.4 mmtpa ethylene cracker unit, and a 5.2 mmtpa Aromatics unit. Phase II will see a 400,000 barrels per day refinery expansion, which will include deeper chemical integration than Phase I.

In China, the biggest of these is Rongsheng Petrochemical Co.’s plant on Zhoushan island, near Ningbo. The 800,000 barrel-a-day operation opened in 2019 and will reach full capacity before year-end. An Indian Oil Corp.-led group is planning a gigantic 1.2 million barrels a day oil-to-chemicals complex on the country’s west coast. Saudi Aramco, as part of its strategy to invest downstream in Asia, has or plans to take a stake in both projects.

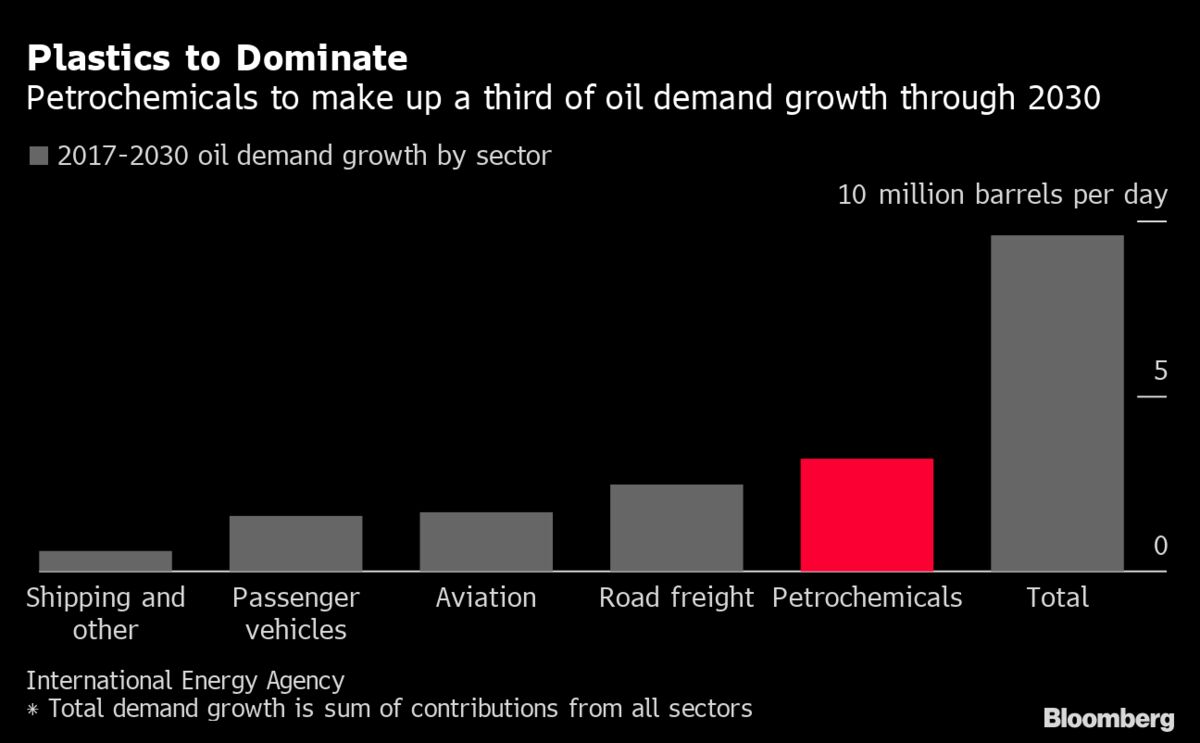

All told, more than half of the refining capacity that comes on stream from 2019 to 2027 will be added in Asia and around 70% to 80% of this will be plastics-focused, according to industry consultant Wood Mackenzie Ltd. Petrochemicals will account for more than a third of global oil demand growth to 2030 and nearly half through 2050, the International Energy Agency predicts.

“It doesn’t make sense now to operate a standalone refinery or a standalone petrochemicals plant for that matter,” said Sushant Gupta, research director for Asia Pacific refining at WoodMac. Smaller facilities will find the new environment challenging, while there’s also a risk of over-capacity, he said.

The big new projects combined with low oil prices will potentially lead to refinery closures in developed markets over 2021 and 2022, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said in a note last month. Some 1.2 million barrels a day of Chinese independent refining capacity will shut down over the next few years, while simpler plants in Japan and Australia will also be stressed, according to Gupta.

The new refineries will lead to a glut of capacity in China, according to Michal Meidan, the director of the China Energy Programme at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. This is partly due to the coronavirus damping global growth expectations and also as efforts to limit single-use plastics increase, she said.

There are still plenty of integrated refineries in the pipeline, however. The Zhoushan plant may be expanded to 1.2 million barrels a day and there are more facilities planned at Shenghong, Yantai and Caofeidian. China will add about 1.6 million barrels a day of integrated capacity by 2025, WoodMac said.

In addition to what Indian Oil is planning, Reliance Industries Ltd. has invested about $20 billion in recent years to double its petrochemicals production capacity and make refining more efficient. Chairman Mukesh Ambani told shareholders last month that the company had proprietary technology to convert gasoline and diesel into the building blocks to produce plastics.

Rongsheng Petrochemical (brand value up 43% to US$2.3 billion) achieved very strong growth this year, rising two places in the chemicals ranking and jumpingfrom 10th to 8th place amongst global chemicals brands. The Chinese brand owns various globally significant facilities, including an integrated refining-petrochemical complex with the refining capacity of 40 million tons per annum.

WASHINGTON – Yesterday, Representatives Raja Krishnamoorthi (IL-08), Abigail Spanberger (VA-07), and Sharice Davids (KS-03) introduced a resolution urging President Biden to use the Defense Production Act to expand short-term oil refinery capacity to eliminate the refining bottleneck that is currently contributing to high gas prices. While historic fuel prices have been primarily driven by high crude oil prices, the most recent spike in gas prices is in large part a product of a lack of refining capacity as oil demand has returned to pre-pandemic levels but global refining capacity has declined by 3,000,000 barrels per day and U.S. capacity alone has declined by 1,000,000 barrels per day. This shortage of oil refining capacity is the result of an unprecedented wave of refinery closures as demand for fuel plummeted during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, despite the current record gas prices and near historic profits, oil companies have shown little interest in restarting refineries that were shuttered during the pandemic. This follows Congressman Krishnamoorthi’s June 2nd letter to President Biden urging him to use the Defense Production Act in the same manner.

While the White House issued letters to the industry yesterday pressing for increased production, the new legislation urges the President to take additional action, stating “in order to ensure sufficient refining capacity to reduce fuel prices and prevent fuel shortages in the near term, the President should use authorities granted him by the Defense Production Act of 1950 to provide targeted technical and financial assistance to restart certain idled refineries for a limited time.” The resolution’s focus on a short-term increase in capacity is to address the current price spike facing consumers while also avoiding long-term impacts on the climate, noting “a long-term expansion of oil production beyond prepandemic levels could put us on a path to climate catastrophe, but restarting idled American oil refineries for a limited time could reduce gas prices and cool inflationary pressures without endangering our climate goals.”

A long-term strategy must include increased crude oil production from countries we can count on as well as ample refining capacity (Read more on the role of U.S. refiners in the global market here).

Shoring up U.S. refining capacityThe United States has the most complex and economic refining industry in the world, but we are losing capacity while the rest of the world is building. We have less refining capacity today than we did just a few years ago. At the beginning of 2020, U.S. refineries were capable of processing 18.976 million barrels of crude oil every day (BPD). In 2022, our capacity is nearly 900,000 BPD less. We’ve permanently shuttered some facilities and are converting others away from gasoline and diesel production to smaller volumes of renewable fuels. With every barrel of refining capacity we’re losing, Asia is building—and then some. Policies like the Renewable Fuel Standard that make it more expensive to manufacture gasoline and diesel in the United States, and regulatory moves to phase out internal combustion engine vehicles are hampering the strength of America’s liquid fuel industries.

(Reuters) Chinese conglomerate Zhejiang Rongsheng Holding Group plans to double capacity of a joint venture refining project to 800 Mbpd in 2020, two years after the first phase starts up, senior company officials said Thursday.

The project, a venture among private companies led by Rongsheng, is planning to start up the 400 Mbpd first phase in 2018, aiming to meet the group"s requirements for petrochemical feedstocks.

The Delaware City refinery has a throughput capacity of 180,000 bpd and a Nelson complexity rating of 13.6. As a result of its configuration and petroleum refinery processing units, Delaware City has the capability to process a diverse heavy slate of crudes with a high concentration of high sulfur crudes making it one of the largest and most complex refineries on the East Coast.

The refinery is located on a 5,000-acre site on the Delaware River, with the ability to accept crude by rail or waterborne cargoes. It possesses an extensive distribution network of pipelines, barges and tankers, truck and rail for the distribution of its refined products.

The Paulsboro refinery is located on approximately 950 acres on the Delaware River in Paulsboro, New Jersey, just south of Philadelphia and approximately 30 miles North of the Delaware City refinery.

The Paulsboro refinery works in combination with the Delaware City refinery to process a wide variety of crude oils. The East Coast refining system produces a variety of finished products including gasoline, heating oil and aviation jet fuel. Paulsboro specifically manufactures Group I lubricant base oils and is the largest producer of Asphalt on the East Coast.

The Toledo refinery has a throughput capacity of approximately 180,000 bpd and a Nelson complexity rating of 11.0. Toledo processes a slate of light, sweet crudes from Canada, the Mid-continent, the Bakken region and the U.S. Gulf Coast. Toledo produces a high volume of finished products including gasoline and ultra-low sulfur diesel, in addition to a variety of high-value petrochemicals including nonene, xylene, tetramer and toluene.

The Toledo petroleum refinery is located on a 282-acre site near Toledo, Ohio, 60 miles south of Detroit. Major units at the Toledo refinery include an FCC unit, a hydrocracker, an alkylation unit and an UDEX unit. Crude is delivered to, and finished products are exported from, the Toledo refinery primarily through a network of pipelines.

The Chalmette Refinery, located outside of New Orleans, Louisiana, is a 185,000 barrel per day, dual-train coking refinery with a Nelson Complexity of 13.0 and is capable of processing both light and heavy crude oil. The facility is strategically positioned on the Gulf Coast with strong logistics connectivity that offers flexible raw material sourcing and product distribution opportunities, including the potential to export products.

The Chalmette refinery processes a variety of crude oils and predominantly produces gasoline, distillates and specialty chemicals. The refinery distributes its products locally and exports to domestic and international markets through pipeline and maritime assets.

The Torrance refinery is located in Torrance, California, and processes a blend of primarily heavy and medium crudes to produce a high-value product slate. The Torrance refinery has a nameplate crude capacity of 166,000 barrels per day with a Nelson Complexity index of 13.8.

The Martinez refinery is PBF Energy’s most recent acquisition. The 157,000 barrel-per-day, dual-coking refinery is located on an 860-acre site in the City of Martinez, 30 miles northeast of San Francisco, California. The refinery is a high-conversion facility with a Nelson Complexity Index of 16.1, making it one of the most complex refineries in the United States. The facility is strategically positioned in Northern California and provides for operating and other synergies with PBF’s Torrance refinery located in Southern California. In addition to refining assets, the transaction includes a number of high-quality onsite logistics assets including a deep-water marine facility, product distribution terminals and refinery crude and product storage facilities with approximately 8.8 million barrels of shell capacity.

8613371530291

8613371530291