is safety valve snitching quotation

In federal cases, Congress not only defines what is a crime that can cost the accused both freedom and property, but it also passes statutes that control how federal judges are allowed to sentence those who have been convicted of federal drug crimes. For instance, federal judges must follow the United States Sentencing Guidelines when sentencing someone upon conviction of a federal crime. For more on sentencing guidelines and how they work, read our discussion in Federal Sentencing Guidelines: Conspiracy To Distribute Controlled Substance Cases.

Sometimes, Congress sets a bottom line on the number of years someone must spend behind bars upon conviction for a specific federal crime. The federal judge in these situations has no discretion: he or she must follow the Congressional mandate.

Of course, there are a tremendous number of federal laws that define federal drug crimes. For purposes of illustration, consider those federal drug crimes that come with either (1) a sentence of 10 years to life imprisonment or (2) those that come with a sentence of 5 to 40 years behind bars, both defined as the mandatory sentences to be given upon conviction for these defined federal drug crimes.

For reference, these refer to the statutory language of 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A) and 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B), which instruct the federal judge on how he or she shall sentence anyone convicted of the manufacture, distribution, or dispensing of a controlled substance (i.e., an illegal drug) or possession with intent to either of these things.

Key here: the judge is given the mandatory minimum number of years that the accused must spend behind bars by Congress via the federal statutory language. A federal judge cannot go below ten (10) years for a federal drug crime based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A). He or she cannot go below five (5) years for a federal drug crime conviction based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B).

Can’t there be any way to get around that set-in-stone bottom line? Yes. There is also a statutory exception which allows the federal judge to dip below that mandatory minimum number of years in some situations. It is called the “Safety Valve” defense.

The law, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), provides for an exception that allows the federal judge some leeway in drug crime convictions where he or she would otherwise be required to follow the mandatory minimum sentencing statute. This is the Safety Value statute. It states as follows:

(f)Limitation on Applicability of Statutory Minimums in Certain Cases.—Notwithstanding anyother provision of law, in the case of an offense under section 401, 404, or 406 of theControlled Substances Act(21 U.S.C. 841, 844, 846), section 1010 or 1013 of theControlled Substances Import and Export Act(21 U.S.C. 960, 963), or section 70503 or 70506 of title 46, the court shall impose a sentence pursuant to guidelines promulgated by the United States Sentencing Commission undersection 994 of title 28without regard to any statutory minimum sentence, if the court finds at sentencing, after the Government has been afforded the opportunity to make a recommendation, that—

(A)more than 4 criminal history points, excluding any criminal history points resulting from a 1-point offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines;

(4)the defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor of others in the offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in section 408 of theControlled Substances Act; and

(5)not later than the time of the sentencing hearing, the defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

Information disclosed by a defendant under this subsection may not be used to enhance the sentence of the defendant unless the information relates to aviolent offense.

The only way to allow for this exception to be applied in a federal sentencing hearing is for the defense to argue its application and to provide authenticated and admissible support for use of the Safety Valve.

How does the defense do this? It takes much more than referencing the exception to the general rule itself. The defense will have to demonstrate the convicted defendant meets the Safety Valve’s five (5) requirements.

Federal sentencing has its own reference manual that is used throughout the United States, called the United States Sentencing Guidelines (“USSG”). We have gone into detail about the USSG and its applications in earlier discussions; to learn more, read:

In short, the idea is that the USSG work to keep things fair for people being sentenced in federal courts no matter which state they are located. Someone convicted in Texas, for instance, should be able to receive the same or similar treatment in a federal sentencing hearing as someone in Alaska, Maine, or Hawaii.

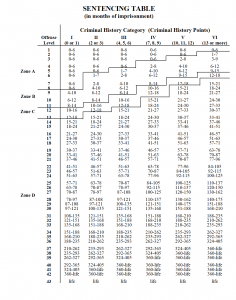

Part of how the Sentencing Guidelines work is by assessing “points.” Offenses are given points. The points tally into a score that is calculated according to the USSG.

Essentially, the accused can be charged with a three-point offense; a two-point offense; or a one-point offense. The number of points will depend on things like if it is a violent crime; violent crimes get more points than non-violent ones. The higher the overall number of points, and the ultimate total score, then the longer the sentence to be given under the USSG.

For a successful safety valve defense, the defense has to show that the total Criminal History Points are four (4) or less. If you have a maximum of four Criminal History points, you have met the first criteria for the safety valve.

Note: prior to the passage of the First Step Act, things were much harsher. If the defense had even two Criminal History Points, then the accused was ineligible for the safety valve. The First Step Act increased the number of points, or score, from one to four as the maximum allowed for application of the safety valve. For more on the First Step Act, see The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 1 of 2 and The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 2 of 2.

Looking at the Safety Valve statute ( 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)), the second step in achieving application of the safety valve defense involves the circumstances of the underlying criminal activity and whether or not it involved violence of threats or violence, or if the defendant possessed a firearm at the time.

It has been my experience that it is pretty common for there to be a firearm of some sort involved in a federal drug crime prosecution. Here, the impact of Texas being a part of the Fifth Judicial District for the United States Court of Appeals (“Fifth Circuit”) is important.

This is because this overseeing federal appeals court has looked at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and its definition of possession of a firearm, and come to a different conclusion that the definition given in the USSG.

Meanwhile, the Fifth Circuit has ruled that under the Safety Valve Statute, the standard for the government is much higher. According to their ruling, in order to be disqualified from application of the safety valve because of possession of a firearm, the defendant has to have been actually in possession of the firearm or in construction possession of it. See, US v. Wilson, 105 F.3d 219 (5th Cir. 1997).

Consider how this works in a federal drug crime conspiracy case. Under the USSG, a defendant can receive two (2) points (“enhancement”) for possession of a firearm even if they never had their hands on the gun. As long as a co-conspirator (co-defendant) did have possession of it, and that possession was foreseeable by the defendant, then the Sentencing Guidelines allow for a harsher sentence (more points).

The position of the Fifth Circuit looks upon this situation and determines that it is one thing for the defendant to have possession of the firearm, and another for there to be stretching things to cover constructive possession when he or she never really had the gun.

This is the example of the importance of effective criminal defense representation, where research reveals that it is easier to achieve a safety valve defense with a reference to case law. The Fifth Circuit allows a situation where someone can get two (2) points under the USSG (“enhancement”) and still be eligible for the safety valve defense.

The commentary to § 5C1.2(2) provides that “[c]onsistent with [U.S.S.G.] § 1B1.3 (Relevant Conduct),” the use of the term “defendant” in § 5C1.2(2) “limits the accountability of the defendant to his own conduct and conduct that he aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused.” See U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, comment. (n.4). This language mirrors § 1B1.3(a)(1)(A). Of import is the fact that this language omits the text of § 1B1.3(a)(1)(B) which provides that “relevant conduct” encompasses acts and omissions undertaken in a “jointly undertaken criminal activity,” e.g. a conspiracy.

Being bound by this commentary, we conclude that in determining a defendant’s eligibility for the safety valve, § 5C1.2(2) allows for consideration of only the defendant’s conduct, not the conduct of his co-conspirators. As it was Wilson’s co-conspirator, and not Wilson himself, who possessed the gun in the conspiracy,the district court erred in concluding that Wilson was ineligible to receive the benefit of § 5C1.2. Because application of § 5C1.2 is mandatory, see U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2 (providing that the court “shall” impose a sentencing without regard to the statutory minimum sentence if the defendant satisfies the provision’s criteria), we vacate Wilson’s sentence and remand for resentencing.

The defense must also be able to prove that the defendant’s role in the underlying criminal offense did not result in the death or bodily injury of someone else to achieve the safety valve defense under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In drug cases, this can mean more than some type of violent scenario. The mere type of drug or controlled substance involved can impact the success of this defense. Sometimes, the drugs themselves are the type that can cause severe harm or death. Several controlled substances can be lethal. In a federal drug case, there is a special definition for death resulting from the distribution of a controlled substance.

If the defense can prove with authenticated and admissible evidence that the defendant did not distribute a drug or controlled substance that ended up with someone’s death, or severe bodily injury, then the safety valve defense will be available to them.

Role adjustments happen when someone is alleged to be involved in a conspiracy, and they act in some type of position of responsibility. They can be a leader, or organizer, or somebody who supervises other people in the operations, all as defined in the USSG.

If you are to achieve the safety valve defense, you cannot receive any “role adjustment” under the Sentencing Guidelines. This must be established to the court by your defense attorney at the sentencing.

The defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

I realize that for many people, this language brings with it the assumption that the defendant has to be a snitch in order to meet this requirement for the safety valve defense. This is not true.

This law does not require a defendant to cooperate against other people in a conspiracy, be it friends or family members or anyone else. It does not force a defendant to turn over new or additional evidence to the police or prosecutors so the government can use it against other defendants. It does not mean the defendant has to cooperate with the government to help them go after unindicted co-conspirators, either.

With an experienced criminal defense lawyer, what it does mean is that the defendant has a meeting with the authorities with the goal of meeting the Safety Valve Statute requirements and no more.

The attorney can limit the scope of the meeting. He or she can make sure that law enforcement follows the rules for the meeting. The meeting is necessary for the defendant to achieve a safety valve defense, so there is no way to avoid a safety valve interview.

To get the sentence that is below the mandatory minimum sentence, the meeting is a must. However, it is not a free-for-all for the government where the defendant is ratting on other people.

One example involves a case where I represented a client before the federal district court in Corpus Christi, the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas. He was among several co-defendants charged in a conspiracy to distribute methamphetamine.

I arranged for my client to have his safety valve meeting as well as establishing the other criteria needed for application of the Safety Valve statute. I was present at the meeting. There was no cooperation regarding the other defendants, and he did nothing more than the minimum to qualify for the defense. He was no snitch.

As a result, the safety valve was applied by the federal judge and my client achieved a safety valve application where he was sentenced to 8 years for distribution of meth: well below the 10 years of the mandatory minimums and the USSG calculation in his case of around 14 years.

Sadly, the same day that my client was sentenced, so were several of the co-conspirator defendants. I was aware that they were also eligible for the safety valve defense. However, the federal agent at the sentencing hearings that day told me that their lawyers never contact the government for a safety valve meeting.

They were never debriefed, so they could not meet the requirements for application of the safety value statute. The judge had no choice –they each had to be sentenced to the mandatory minimum sentences under the law.

As every criminal defense lawyer knows, there are some very draconian minimum mandatory sentences in Federal criminal court. There are federal minimum mandatory sentences for certain drug offenses, firearm offenses, and for defendants who have certain convictions. There are two ways to break the minimum mandatory sentence, which then allows a judge to sentence you below the minimum mandatory. The first is called “substantial assistance.” Basically, if you snitch and the government wants your information, uses your information, and they determine that it was worthy of a sentence below the minimum mandatory, they can file a substantial assistant motion and if granted by the judge, the minimum mandatory would no longer apply. You can only get less than the minimum mandatory sentence if the prosecutor files the motion. If they decide not to file the motion, the judge must sentence you to the minimum mandatory sentence up to the maximum sentence. But what if you don’t want to snitch? What if you don’t have any information that the government is interested in? There is one more option that will allow the judge to sentence you below the minimum mandatory sentence: Safety Valve.

The “Safety Valve” provision is a provision of law codified in 18 United States Code §3553(f). It specifically allows a judge to sentence you below the minimum mandatory required by law. However, you must be eligible. There is also a two level reduction in the sentencing guidelines under United States Sentencing Guidelines §2D1.1(b)(17).

A common requirement that disqualifies people is the prior criminal record requirement. Basically, anything other than a minor one time conviction will disqualify you. However, old convictions may not count and some minor convictions also do not count. There is a whole section in federal sentencing guidelines manual that addresses which prior convictions count and how many points are assessed.

In order to get safety valve, you, through your criminal defense attorney, must contact the prosecuting attorney before your sentencing hearing, and tell them that you want to provide them with a statement. You must be willing to tell them everything you know about the offense, who else was involved, and you must be forthcoming and truthful. It will be up to the judge to determine whether you meet this requirement. You should not wait until the last minute either, as the prosecutor has no duty to take your statement within a short period of time before the sentencing hearing and the judge has no duty to continue your sentencing hearing to give you time to provide the government with a statement.

One difference between Safety Valve and Substantial Assistance is that there is no requirement for you to cooperate against anyone else. So, once your provide the information to the prosecutor, you should become eligible to seek safety valve at your sentencing, without having to cooperate against anyone else.

If you are not convicted under one of these statutes, there is no Safety Valve option. For example, Safety Valve is not an option for someone convicted under the Aggravated Identity Theft statute that carries a 2 year minimum mandatory sentence consecutive to any underlying sentence. Similarly, if you were convicted of similar conduct to those eligible for safety valve, but were convicted under a statute not listed above, you still would not be safety valve eligible. For example, if you were convicted fo possession with intent to distribute cocaine while aboard a vessel subject to United States jurisdiction in violation of 46 U.S.C. app. §1903(a), you would not be eligible for safety valve, even though someone convicted of the same conduct on land would be eligible.

After graduation, Mr. Lasnetski accepted a position as a prosecutor at the State Attorney’s Office in Jacksonville. During the next 6 1/2 years as a prosecutor, Mr. Lasnetski tried more than 50 criminal trials, including more than 40 felony trials. He was promoted in 2007 to Division Chief of the Repeat Offender Unit. Mr. Lasnetski was also a full time member of the Homicide Prosecution Team. In 2008, Mr. Lasnetski formed the Law Office of Lasnetski Gihon Law and began defending citizens in criminal court. He represents clients in both State and Federal criminal courts.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Many federal criminal defense attorneys are not aware of the pitfalls of the federal safety valve provisions. Persons charged with federal drug crimes need to retain an experienced criminal attorney familiar with all aspects of federal criminal law. An inexperienced or unknowing lawyer can expose a client to catastrophic risks. Here is why.

As we are all keenly aware, the federal government’s “war on drugs” is ensnaring hundreds of people with little or no criminal records who are caught up, for a myriad of reasons, with the distribution of drugs. This can range from a person carrying cash for a friend to pay for an airline ticket, to delivering a package to another person in exchange for cash to pay the rent or feed a child. Because of very harsh federal sentencing laws, the smallest players in a drug ring often end up being the most harshly treated. Most of time this is because the leaders of drug operations very often end up cooperating against others – including those below them whose “loyalty” they often gained through fear and threats of harm. Oftentimes, those persons caught on the lowest rungs of a drug conspiracy find themselves with few alternatives because they do not have significant information to provide to federal prosecutors, who retain exclusive control over who gets cooperation departures under the federal sentencing guidelines. As a result, defendants with minor or minimal culpability in a drug operation frequently end up on the receiving end of prosecutions involving tremendously high sentencing guidelines and, more critically, large minimum mandatory sentences.

In many situations, the only relief from mandatory sentences for those with little or no criminal history is the so-called “safety valve.” Many lawyers talk about the safety valve, but very few understand what it is and what it truly entails. It is perhaps the most misunderstood and most difficult opportunity for relief from mandatory minimum sentences and the sentencing guidelines. Federal crimes lawyers who do not specialize in federal criminal defense work run the risk of harming their clients through misguided efforts to gain relief under the safety valve provision.

It is critical to remember that there are only two ways to avoid minimum mandatory sentences upon conviction for a drug trafficking or drug conspiracy offense in federal court. One way is to cooperate with law enforcement and provide “substantial assistance” in the prosecution of others under section 5K1.1 of the guidelines. The other is to seek relief under the safety valve — Section 5C1.2 of the federal sentencing guidelines. (18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)) This section allows a judge to reduce federal sentencing guidelines and ignore mandatory minimum sentences in determining punishment for eligible defendants.

But while understanding the possible benefits of relief under the safety valve is easy, becoming eligible for the relief is more difficult and fraught with peril for the unwary defendant. In fact, a failed attempt to gain “safety valve” relief can have a tremendously negative impact on a federal criminal defendant.

Section 5C1.2 allows guideline reduction and relief from mandatory minimum sentences when 1) a defendant ‘s criminal history is one point or less under the guidelines, and 2) the defendant truthfully discloses before sentencing everything the defendant knows about his own actions and those who participated in the crime with him. While a defendant is not required to testify in court or become a cooperator, the section does requires that he sit down with federal agents and prosecutors and tell them everything he knows about the charged crime. While a defendant won’t be a witness against others in his case, he still must tell on them. Government agents can affirmatively use the defendant’s information against others in the case without any limitation.

For example, if the defendant tells agents that he stored drugs in his brother’s house, agents can use that information to get a search warrant and raid that house for evidence, even though the defendant would never want his brother to be harmed. Moreover, because the defendant would not be a “cooperator,” prosecutors would be free to name him in their search warrant applications and make no effort to hide the source of their information.

Talking to the government in the context of a safety valve interview can potentially expose the client to consequences worse than those faced by cooperating witnesses.

Next, the attorney has to be 100% certain that the client is telling everything he knows and is not holding back information about himself or others. This requires that attorney be sure of what the government knows in the case before allowing a client to meet for a safety valve interview. If the government thinks that the client is lying, they can make the safety valve process impossible by telling the court about their impressions. If the government can prove the client is lying, then a court is free to increase a client’s sentence for obstruction of justice. Even worse, a client may also lose guideline point reductions for accepting responsibility for the offense and become subject to harsh mandatory minimum sentences.

A defense attorney has to know what the evidence the government has before allowing his client to even think about the safety valve. Anything less can expose the client to catastrophic risk.

The bottom line is that defendants considering a “safety valve” reduction had better have counsel who is experienced in federal criminal law and the pitfalls of federal criminal statutes – even those designed to help defendants. Before becoming a defense attorney, I spent almost a decade prosecuting federal criminal cases in U.S. District Court in Maryland. If you have any questions, contact Federal defense attorney Andrew C. White at Silverman, Thompson, Slutkin & White. There is no situation with which we are not familiar.

The safety valve is a provision in the Sentencing Reform Act and the United States Federal Sentencing Guidelines that authorizes a sentence below the statutory minimum for certain nonviolent, non-managerial drug offenders with little or no criminal history.FIRST STEP Act was signed into law in December 2018, which expanded the safety valve to include offenders with up to four criminal history points, excluding 1-point offenses, such as minor misdemeanors.

Commission, 2012 Federal Sentencing Statistics. http://www.ussc.gov/Data_and_Statistics/Federal_Sentencing_Statistics/State_District_Circuit/2012/index.cfm

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Cooperation affects a remarkable number of federal sentences. For fiscal year 2017, the U.S. Sentencing Commission reported that federal prosecutors sought cooperation reduced sentences for 7,128 defendants — 10.8 percent of all federal criminal defendants sentenced.

Federal prosecutors have long used cooperators to help prove crimes. While the cooperation continues, it needs to be secret in order to avoid alerting wrongdoers who are still being investigated but not yet charged. So judges seal from public view cooperation that has not been completed. The need for that type of secrecy generally ends when the cooperation ends, in most cases at the time the cooperator is sentenced.

When mandatory guidelines and mandatory minimum sentences arrived in the late 20th century, federal defendants gained a new incentive to cooperate: Only a prosecution motion based upon a defendant’s “substantial assistance” (a “5K1.1” motion to those in the know) could generate a sentence below the guideline range or below an otherwise mandatory sentencing floor created by statute.

In 2001, the United States Judicial Conference (the federal judiciary’s policy-setting body) made the statement-of-reasons portion of a judge’s sentencing document publicly unavailable after the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) reported “an emerging problem of inmates pressuring other inmates for copies of their presentence reports and statements of reasons to learn if they are informants.”

In a 2015 high-profile Texas case, United States v. McCraney, federal prosecutors were pressed to justify their request that cooperation documents remain sealed despite a journalist’s request to see them. Prosecutors called as witnesses a supervisory intelligence officer for the Bureau of Prisons, a special investigator at a Federal Correctional Complex, and an assistant United States attorney, possessing a combined 64 years of experience with cooperating defendants. Their testimony was explosive. For several hours these officials described to a federal judge “specific cases in which disclosure of the identity of an informant, and even disclosure that an inmate had relayed any information at all to prison officials, resulted in retaliation in the form of realistic and believable threats of violence, actual violence, and death.”

That same year, the Federal Judicial Center surveyed federal district judges, United States Attorneys’ Offices, federal defenders, court-appointed defense counsel, and chief probation and pretrial services officers about harm to cooperators. The survey, published in 2016, revealed that cooperating defendants “were most likely to be harmed or threatened when in some type of custody,” that “court documents or court proceedings [were frequently] the source for identifying cooperators,” that concerns about harm or its threat “affected the willingness” of defendants and others to cooperate, and that it was “a significant problem.”

Following the survey, the conference’s Committee on Court Administration and Case Management (CACM) determined that further action, including formal rulemaking, was necessary to protect cooperators. But the federal rulemaking process is time-consuming.

But the proposal was controversial. So the director of the federal courts’ Administrative Office appointed the Task Force on Protecting Cooperators, “charged with taking a broad look at this issue and recommending actions by all entities concerned, including the Bureau of Prisons, the Criminal Division of the Department of Justice, the U.S. Marshals Service, and United States Attorneys.”

Meanwhile, in response to increasing requests from prisoners and third parties for court documents — including transcripts — to reveal whether a prisoner has cooperated,

In summary, today’s federal sentencing landscape includes courts where the courtroom is physically closed for any cooperation discussion; courts where the courtroom is not closed but any cooperation discussion occurs out of public hearing in chambers or at a private sidebar (some judges hold a pro forma sidebar even where there is no cooperation so that observers cannot infer cooperation from the sidebar); courts where everything is done in open court without sidebars; courts where the lawyers submit cooperation details under seal but the judge announces the sentencing rationale in open court; courts where transcripts of some or all of the above are sealed; courts where virtually nothing is sealed; courts where docket entries are structured so that outsiders cannot determine whether a defendant has cooperated; and other variations. Pity the journalist or citizen who seeks to know with certainty what happened at a particular federal sentencing.

In its unpublished interim report some months ago, the Task Force on Protecting Cooperators focused its first recommendations on corrective activity by the Bureau of Prisons, because that is where the problem of violence primarily lies; as a result, the director of the federal courts’ Administrative Office made a number of proposals to BOP in a letter that is not yet public.

This would mark a return to some of the earlier practical obscurity of court files and would be somewhat analogous to the treatment of social security and immigration civil cases under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 5.2(c). Lawyers, however, would have remote access to all the plea and sentencing folders so that they could see how defendants are treated in similar cases and make proportionality arguments for their own clients.

The answer, I say, is, “No.” Transparency is paramount to the federal judicial role. England’s notorious 17th-century Star Chamber discredited the respectability of secret judicial proceedings forever.

The U.S. Sentencing Commission recognizes that Congress requires “[t]he sentencing judge [to] state the reasons for reducing a sentence” for substantial assistance, but it asserts that a “court may elect to provide its reasons to the defendant in camera and in writing under seal for the safety of the defendant or to avoid disclosure of an ongoing investigation.”

We cannot be confident that sealed sidebars or chambers conferences will even solve the prison retaliation issue. It is impossible to eliminate all cooperation information because there are so many other available sources — for example, cooperation implications drawn from recurrent delays in sentencing a particular defendant; a reduced charge in a conspiracy; general or specific knowledge among co-defendants, their families, and associates; materials about a witness that a statute

Some have suggested that it is acceptable to hide the role of cooperation in individual sentences as long as the Sentencing Commission makes aggregate data available.

Now I do not mean to suggest that the specifics of cooperation or the existence of ongoing cooperation always need to be disclosed. That information appears in materials the lawyers file or things they say to the judge. If there is a strong countervailing interest, federal appellate cases permit some sealing of such materials for a limited time on a case-by-case basis.

Let me be clear: No federal judge wants to be responsible for the death or assault of a sentenced defendant who cooperated. The judge has determined the offender’s punishment, and it does not include violence in prison. But the judge’s role is limited. The judge cannot determine the facility BOP will select for a particular defendant and the resulting risks. The judge cannot disguise the nature of the crime of conviction — for example, a crime like child molesting that might provoke violence against the offender in prison. The judge cannot ensure the adequacy of prison medical care. These and other consequences are all outside the federal judiciary’s role. What the judge can do — must do — is preserve the American public’s trust in the integrity and transparency of the federal judicial system. Americans are entitled to know the role cooperation plays in federal criminal law and sentencing. If the threat of violence deters some defendants from cooperating, then the Justice Department must deal with that consequence in evaluating how it prosecutes cases, or find the resources and the way to help BOP do its job of making prisoners, including cooperating prisoners, safe.

At the end of the day, encouraging or discouraging cooperation is not the business of federal judges. That is the executive branch’s role. Judges constitute an independent branch of government with distinctive responsibilities. Our charge is to sentence convicted defendants fairly, based on all the facts and circumstances and the law, and to explain as clearly as possible to the public, the defendants, and the victims how we reach the sentence we pronounce. As some of us say, a sentencing proceeding is a community morality play where society’s values are publicly applied and affirmed. We should not let the violence of prisoners — even a violence that BOP apparently cannot control — drive federal sentencing underground.

See Robert J. Conrad, Jr. & Katy L. Clements, The Vanishing Criminal Jury Trial: From Trial Judges to Sentencing Judges, 86 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 99 (2018).

Since Booker v. United States, 543 U.S. 220 (2005), the national percentage has ranged between 14.7% and 10.8%. U.S. Sentencing Commission, 2005 Sourcebook of Federal Sentencing Statistics 292-93; U.S. Sentencing Commission, 2017 Sourcebook of Federal Sentencing Statistics S-53 tbl.N. Fed. R. Crim. P. 35(b) also allows for a reduced sentence for substantial assistance after sentencing, upon a government motion filed within one year of the sentence. The numbers and percentages are larger if postsentencing motions for cooperation under Rule 35(b) are included. The Sentencing Commission reported that adding them to 5K1.1s for fiscal 2010 increased the percentage from 11.5% to 13.0%. U.S. Sentencing Commission, The Use of Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 35(b) 8 (2016).

At the other extreme, for Washington Western it is 2.6%; for Virginia Eastern, 3.1%. U.S. Sentencing Commission, 2017 Sourcebook of Federal Sentencing Statistics 264, 267.

The government makes such a motion only where the cooperation results in “substantial assistance in the investigation or prosecution of another person who has committed an offense,” and the decision to make the motion is entirely discretionary with the government. Guideline 5K1.1. In a variant sentence, judges may give credit for cooperation that did not yield other convictions. I have been unable to locate Sentencing Commission data that isolate this factor.

Alternatively for certain narcotics crimes, defendants who truthfully tell the prosecution all they know about offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or a common scheme or plan and meet certain other criteria can obtain a sentence below the statutory minimum as well as a two-level decrease in total offense level whether or not the information is useful. Guideline 5C1.2 (colloquially known as the safety valve). The number of drug cases where defendants qualify for the safety valve — 6,198 cases nationally, U.S. Sentencing Commission, 2017 Sourcebook of Federal Sentencing Statistics 115 tbl.44) — approaches the number of 5K1.l motions (7,128). To my knowledge, application of 5C1.2 has not been the subject of attention concerning “cooperation.”

From the Administrative Office of the United States Court on Policy Change Restricting Routine Public Disclosure of the Statement of Reasons and Revised Forms for Judgments in a Criminal Case (AO245B-AO245I), Aug. 13, 2001.

Caren Myers Morrison, Privacy, Accountability, & the Cooperating Defendant: Towards a New Role for Internet Access to Court Records, 62 Vand. L. Rev. 921, 957-58 (2009), describes the website’s operation in 2009.

Mem. from Committee on Court Administration and Case Management, Committee on Criminal Law, & the Defender Services Committee to Article III Judges, Sept. 17, 2014 (noting that, “[d]ue to increased access to criminal case filings, there is a growing concern that cooperation information found in these files is being used to threaten or harm cooperating individuals, particularly those who are incarcerated”).

With at least seven stages of formal comment and review, “it usually takes two to three years for a suggestion to be enacted as a rule.” James C. Duff, The Federal Rules of Practice and Procedure, Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

Mem. from Committee on Court Administration and Case Management of the Judicial Conference of the United States, June 30, 2016 (providing interim guidance to district court judges).

Mem. from the Administrative Office of the United States Courts Regarding the Formation of the Task Force on Protecting Cooperators, Feb. 10, 2017. The Task Force consists of judges from the Criminal Rules Committee, the Criminal Law Committee, and CACM, along with advisory participants from the Department of Justice, the Bureau of Prisons, the Federal Public Defenders, and a Clerk of Court.

Advisory Committee on Criminal Rules, April 17, 2017 Minutes 4 (“The BOP working group report describes widespread attempts by inmates to determine if someone newly designated to a particular facility has been a cooperator. In many places a newly arriving inmate is asked for ‘his papers’ (whatever documents the inmate has, such as a PSR, sentencing minutes, judgment and commitment order, transcripts, etc.). If the inmate says he doesn’t have his papers, he is told to get them. As a result, inmates ask people outside the prison, often their relatives, to get their papers. There have also been an increasing number of requests by inmates asking the district courts to send their papers to them in prison.”). Accord United States v. McCraney, 99 F. Supp. 3d 651, 656 (E.D. Tex. 2015) (citing BOP Supervisory Intelligence Officer testimony that “inmates often write to friends and family members who are not incarcerated and ask them to research other inmates on LexisNexis, Google, or Pacer to determine whether they provided substantial assistance to the Government.”).

Secrecy is the Star Chamber’s abiding reputation, although historians point out that its secrecy was in fact limited. Daniel L. Vande Zande, Coercive Power and the Demise of the Star Chamber, 50 Am. J. Legal Hist. 326 (2010).

Rita, 551 U.S. at 357–58. In the criminal trial context, Chief Justice Burger quoted Jeremy Bentham: “Without publicity, all other checks are insufficient; in comparison of publicity, all other checks are of small account.” Richmond Newspapers, Inc. v. Virginia, 448 U.S. 555, 569 (1980) (quoting Jeremy Bentham, Rationale of Judicial Evidence 524 (1827)).

Model Penal Code § 10.01(4) cmt. e (Am. Law Inst. 1962). As the Second Circuit said in United States v. Amodeo, 71 F.3d 1044, 1048 (2d Cir. 1995): “Without monitoring . . . the public could have no confidence in the conscientiousness, reasonableness, or honesty of judicial proceedings. Such monitoring is not possible without access to testimony and documents that are used in the performance of Article III functions.” (Amodeo was not a sentencing case.)

Ironically, the commission itself says the “advisory guideline system continues to assure transparency by requiring that sentences be based on articulated reasons stated in open court that are subject to appellate review.” USSG Ch. 1, Pt. A, intro. comment.

Interpreting § 3553(c), the Second Circuit has found it improper to sentence in the judge’s robing room. United States v. Alcantara, 396 F.3d 189, 206 (2d Cir. 2005) (“It is clear that ‘open court’ as used in these rules refers to a courtroom to which the public has access.”). See also United States v. Molina, 356 F. 3d 269, 277 (2d Cir. 2004) (one of Congress’s goals in § 3553(c) was “to enable the public to learn why [the] defendant received a particular sentence”). Justice Department policy is also against courtroom closure, requiring 60-day recurrent review of sealing. 28 CFR § 50.9. See also S. Attorneys’ Manual 9-5.150.

For many courtrooms these days, there are neither journalists nor public court-watchers in attendance; thus sealing the transcript effectively forecloses public access.

It is reported that prisoners quickly become adept at figuring out what various docketing devices, such as skipped numbers or missing documents, are designed to hide or disguise.

Supreme Court and circuit court cases recognize a presumptive common law right of public access to judicial documents and a qualified First Amendment right of access to criminal proceedings. See, e.g., Press-Enterprise Co. v. Superior Court, 478 U.S. 1 (1986) (transcript of preliminary hearing); Press-Enterprise Co. v. Superior Court, 464 U.S. 501 (1984) (state court criminal jury selection proceedings); United States v. Kravetz, 706 F.3d 47, 57, 59 (1st Cir. 2013) (sentencing memoranda and letters to a judge). But where the lawyers are in agreement and media are not interested, there is no challenge to courtroom closure or seal.

It is not my purpose here to challenge the use of cooperation in criminal prosecutions. But it is not an unmitigated blessing. See, e.g., Alexandra Natapoff, Criminal Informants and the Erosion of American Justice (2009) (especially chapter 4); Miriam Heckler Baer, Cooperation’s Cost, 88 Wash. U. L. Rev. 903 (2011). The public needs to be informed of cooperation’s role in federal criminal prosecution not just in the abstract but in the specifics.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

8613371530291

8613371530291