is safety valve snitching for sale

As every criminal defense lawyer knows, there are some very draconian minimum mandatory sentences in Federal criminal court. There are federal minimum mandatory sentences for certain drug offenses, firearm offenses, and for defendants who have certain convictions. There are two ways to break the minimum mandatory sentence, which then allows a judge to sentence you below the minimum mandatory. The first is called “substantial assistance.” Basically, if you snitch and the government wants your information, uses your information, and they determine that it was worthy of a sentence below the minimum mandatory, they can file a substantial assistant motion and if granted by the judge, the minimum mandatory would no longer apply. You can only get less than the minimum mandatory sentence if the prosecutor files the motion. If they decide not to file the motion, the judge must sentence you to the minimum mandatory sentence up to the maximum sentence. But what if you don’t want to snitch? What if you don’t have any information that the government is interested in? There is one more option that will allow the judge to sentence you below the minimum mandatory sentence: Safety Valve.

The “Safety Valve” provision is a provision of law codified in 18 United States Code §3553(f). It specifically allows a judge to sentence you below the minimum mandatory required by law. However, you must be eligible. There is also a two level reduction in the sentencing guidelines under United States Sentencing Guidelines §2D1.1(b)(17).

A common requirement that disqualifies people is the prior criminal record requirement. Basically, anything other than a minor one time conviction will disqualify you. However, old convictions may not count and some minor convictions also do not count. There is a whole section in federal sentencing guidelines manual that addresses which prior convictions count and how many points are assessed.

In order to get safety valve, you, through your criminal defense attorney, must contact the prosecuting attorney before your sentencing hearing, and tell them that you want to provide them with a statement. You must be willing to tell them everything you know about the offense, who else was involved, and you must be forthcoming and truthful. It will be up to the judge to determine whether you meet this requirement. You should not wait until the last minute either, as the prosecutor has no duty to take your statement within a short period of time before the sentencing hearing and the judge has no duty to continue your sentencing hearing to give you time to provide the government with a statement.

One difference between Safety Valve and Substantial Assistance is that there is no requirement for you to cooperate against anyone else. So, once your provide the information to the prosecutor, you should become eligible to seek safety valve at your sentencing, without having to cooperate against anyone else.

If you are not convicted under one of these statutes, there is no Safety Valve option. For example, Safety Valve is not an option for someone convicted under the Aggravated Identity Theft statute that carries a 2 year minimum mandatory sentence consecutive to any underlying sentence. Similarly, if you were convicted of similar conduct to those eligible for safety valve, but were convicted under a statute not listed above, you still would not be safety valve eligible. For example, if you were convicted fo possession with intent to distribute cocaine while aboard a vessel subject to United States jurisdiction in violation of 46 U.S.C. app. §1903(a), you would not be eligible for safety valve, even though someone convicted of the same conduct on land would be eligible.

After graduation, Mr. Lasnetski accepted a position as a prosecutor at the State Attorney’s Office in Jacksonville. During the next 6 1/2 years as a prosecutor, Mr. Lasnetski tried more than 50 criminal trials, including more than 40 felony trials. He was promoted in 2007 to Division Chief of the Repeat Offender Unit. Mr. Lasnetski was also a full time member of the Homicide Prosecution Team. In 2008, Mr. Lasnetski formed the Law Office of Lasnetski Gihon Law and began defending citizens in criminal court. He represents clients in both State and Federal criminal courts.

Safety Valve is a provision codified in 18 U.S.C. 3553(f), that applies to non-violent, cooperative defendants with minimal criminal record without a leadership enhancement convicted under several federal criminal statutes. Congress created Safety Valve in order to ensure that low-level participants of drug organizations were not disproportionately punished for their conduct.

Generally applying to drug crimes with a mandatory minimum, Safety Valve has two major benefits for individuals charged with those crimes. Specifically, the two benefits of Safety Valve are:

The first benefit of Safety Valve is the ability to receive a sentence below a mandatory minimum on certain types of drug cases. Some drug charges have a mandatory minimum i.e. 5 years, 10 years. That means even if the person’s guidelines are lower than the mandatory minimum and the judge wants the sentence the individual below the mandatory minimum, the judge is legally unable to do so because that would be an illegal plea. If the Court determines that the individual meets the requirements of Safety Valve under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), the Judge is able to sentence the individual to a term that is less than the mandatory minimum.

The second benefit of safety valve is a two-point reduction in total offense conduct. Since 2009, federal sentencing guidelines are discretionary rather than binding. With that being said, federal sentencing guidelines still act as the Judge’s starting point in determining what the appropriate sentence on a case is. The higher the total offense score, the higher is the corresponding suggested sentencing range. A two-level difference can make a difference in months if not years of the sentence. Each point counts toward ensuring the lowest possible sentence.

The Defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor of others in the offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in section 408 of the Controlled Substance Act, and

Not later than the time of the sentencing hearing, the defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

In order to establish eligibility for Safety Valve, the Defendant has the burden of proof to establish that s/he meets the five requirements by a preponderance of evidence. That is to say, the Defendant must prove by 51% that the Defendant meets all the requirements of eligibility. These five Safety Valve Requirements are explained in greater detail below.

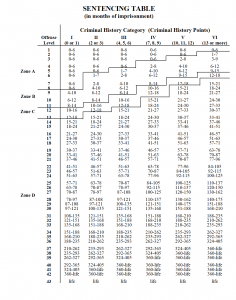

The first requirement of Safety Valve is that the individual has a limited criminal record. The U.S. Sentencing Guidelines assign a certain number of points to prior convictions. The more serious the crime, and the longer the sentence, the more corresponding criminal history points it carries.

More than 4 criminal history points, excluding any criminal history points resulting from a 1-point offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines;

The second requirement of Safety Valve is that the individual did not use violence, credible threats of violence or possess a firearm or other dangerous weapon. Importantly, an individual can be disqualified from Safety Valve based on the conduct of co-conspirators, if the Defendant “aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused” the co-conspirator’s violence or possession of a firearm or another dangerous weapon. Thus, use of violence or possession of a weapon by a co-defendant does not disqualify someone from Safety Valve, unless the individual somehow helped or instructed the co-defendant to engage in that conduct.

To be disqualified from Safety Valve, possession of a firearm or another dangerous weapon can either be actual possession or constructive possession. Actual possession involves the individual having the gun in their hand or on their person. Constructive possession means that the individual has control over the place or area where the gun was located. Importantly, the possession of a firearm or a dangerous weapon needs to be related to the drug crime, as the statute requires possession of same “in connection with the offense.” However, “in connection with the offense” is a relatively loose standard, in that presence of the firearm or dangerous instrument in the same location as the drugs is enough to disqualify someone from Safety Valve.

The third requirement of Safety Valve is that the offense conduct did not result in death or serious bodily injury to any person. Serious bodily injury for the purposes of Safety Valve is defined as “injury involving extreme physical pain or the protracted impairment of a function of a bodily member, organ, or mental faculty; or requiring medical intervention such as surgery, hospitalization, or physical rehabilitation.”

The fourth requirement of Safety Valve is that the Defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager or supervisor of others in the office. An individual will be disqualified from safety valve if s/he exercised any supervisory power or control over another participant. Individuals who receive an enhancement for an aggravating role under §3B1.1 are not eligible for safety valve. Similarly, in order to be eligible for Safety Valve, an individual does not need to receive a minor participant role reduction.

Isolated instances of asking someone else for help do not result in the aggravating role enhancement. As the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit has held in United States v. McGregor, 11 F.3d 1133, 1139 (2d Cir. 1993), aggravated role enhancement did not apply to “one isolated instance of a drug dealer husband asking his wife to assist him in a drug transaction.” Similarly, in United States v. Figueroa, 682 F.3d 694, 697-98 (7th Cir. 2012); the Seventh Circuit declined to apply a leadership enhancement for a one-time request from one drug dealer to another to cover him on a sale.

The fifth and final Safety Valve requirement is that the individual meet with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for a Safety Valve proffer. A Safety Valve proffer is different from a regular proffer in that in a safety valve proffer, the individual is only required to truthfully proffer about his or her own conduct.

In contrast, in a non-safety valve proffer, the individual is required to truthfully provide information about his or her own criminal conduct, as well as the criminal conduct of others. In order to meet this requirement, the individual must provide a full and complete disclosure about their own criminal conduct, not just the allegations that are charged in the offense. There is no required time as to when someone goes in for a safety valve proffer, except that it must take place sometime “before sentencing.”

Not all charges with mandatory minimums qualify for Safety Valve relief. Rather, the criminal charge must be enumerated in 18 U.S.C. 3553(f). The following criminal charges are eligible for Safety Valve:

Under the First Step Act, the eligibility for Safety Valve relief was expanded to more individuals. Specifically, The First Step Act, P.L. 115-391, broadened the safety valve to provide relief for:

Prior to the enactment of the First Step Act, individuals could have a maximum of 1 criminal history point in order to be eligible for Safety Valve relief. Similarly, individuals who were prosecuted for possession of drugs aboard a vessel under the Maritime Drug Enforcement Act, were not eligible for Safety Valve relief. After the passing of the First Step Act, individuals prosecuted under Maritime Drug Enforcement Act, specifically 46 U.S.C. 70503 or 46 U.S.C. 70506 are eligible for Safety Valve relief.

Safety Valve is an important component of plea negotiations on federal drug cases and should always be explored by experienced federal counsel. If you have questions regarding your Safety Valve eligibility, please contact us today to schedule your consultation.

Many federal criminal defense attorneys are not aware of the pitfalls of the federal safety valve provisions. Persons charged with federal drug crimes need to retain an experienced criminal attorney familiar with all aspects of federal criminal law. An inexperienced or unknowing lawyer can expose a client to catastrophic risks. Here is why.

As we are all keenly aware, the federal government’s “war on drugs” is ensnaring hundreds of people with little or no criminal records who are caught up, for a myriad of reasons, with the distribution of drugs. This can range from a person carrying cash for a friend to pay for an airline ticket, to delivering a package to another person in exchange for cash to pay the rent or feed a child. Because of very harsh federal sentencing laws, the smallest players in a drug ring often end up being the most harshly treated. Most of time this is because the leaders of drug operations very often end up cooperating against others – including those below them whose “loyalty” they often gained through fear and threats of harm. Oftentimes, those persons caught on the lowest rungs of a drug conspiracy find themselves with few alternatives because they do not have significant information to provide to federal prosecutors, who retain exclusive control over who gets cooperation departures under the federal sentencing guidelines. As a result, defendants with minor or minimal culpability in a drug operation frequently end up on the receiving end of prosecutions involving tremendously high sentencing guidelines and, more critically, large minimum mandatory sentences.

In many situations, the only relief from mandatory sentences for those with little or no criminal history is the so-called “safety valve.” Many lawyers talk about the safety valve, but very few understand what it is and what it truly entails. It is perhaps the most misunderstood and most difficult opportunity for relief from mandatory minimum sentences and the sentencing guidelines. Federal crimes lawyers who do not specialize in federal criminal defense work run the risk of harming their clients through misguided efforts to gain relief under the safety valve provision.

It is critical to remember that there are only two ways to avoid minimum mandatory sentences upon conviction for a drug trafficking or drug conspiracy offense in federal court. One way is to cooperate with law enforcement and provide “substantial assistance” in the prosecution of others under section 5K1.1 of the guidelines. The other is to seek relief under the safety valve — Section 5C1.2 of the federal sentencing guidelines. (18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)) This section allows a judge to reduce federal sentencing guidelines and ignore mandatory minimum sentences in determining punishment for eligible defendants.

But while understanding the possible benefits of relief under the safety valve is easy, becoming eligible for the relief is more difficult and fraught with peril for the unwary defendant. In fact, a failed attempt to gain “safety valve” relief can have a tremendously negative impact on a federal criminal defendant.

Section 5C1.2 allows guideline reduction and relief from mandatory minimum sentences when 1) a defendant ‘s criminal history is one point or less under the guidelines, and 2) the defendant truthfully discloses before sentencing everything the defendant knows about his own actions and those who participated in the crime with him. While a defendant is not required to testify in court or become a cooperator, the section does requires that he sit down with federal agents and prosecutors and tell them everything he knows about the charged crime. While a defendant won’t be a witness against others in his case, he still must tell on them. Government agents can affirmatively use the defendant’s information against others in the case without any limitation.

For example, if the defendant tells agents that he stored drugs in his brother’s house, agents can use that information to get a search warrant and raid that house for evidence, even though the defendant would never want his brother to be harmed. Moreover, because the defendant would not be a “cooperator,” prosecutors would be free to name him in their search warrant applications and make no effort to hide the source of their information.

Talking to the government in the context of a safety valve interview can potentially expose the client to consequences worse than those faced by cooperating witnesses.

Next, the attorney has to be 100% certain that the client is telling everything he knows and is not holding back information about himself or others. This requires that attorney be sure of what the government knows in the case before allowing a client to meet for a safety valve interview. If the government thinks that the client is lying, they can make the safety valve process impossible by telling the court about their impressions. If the government can prove the client is lying, then a court is free to increase a client’s sentence for obstruction of justice. Even worse, a client may also lose guideline point reductions for accepting responsibility for the offense and become subject to harsh mandatory minimum sentences.

A defense attorney has to know what the evidence the government has before allowing his client to even think about the safety valve. Anything less can expose the client to catastrophic risk.

The bottom line is that defendants considering a “safety valve” reduction had better have counsel who is experienced in federal criminal law and the pitfalls of federal criminal statutes – even those designed to help defendants. Before becoming a defense attorney, I spent almost a decade prosecuting federal criminal cases in U.S. District Court in Maryland. If you have any questions, contact Federal defense attorney Andrew C. White at Silverman, Thompson, Slutkin & White. There is no situation with which we are not familiar.

Over the years I have been retained by a few criminal defense clients after they had bad experience with a prior lawyer. The reasons for switching defense attorneys in midstream vary: sometimes it is concern over the lawyer’s competence, or concern that their case is not getting the attention it deserves, or even that they just don’t see eye to eye with their lawyer. One of the most common, and disturbing reasons though is that the client feels that their prior attorney ripped them off. These complaints generally involve “flat-fee” retainer agreements in which a lawyer and a client agree upon a fixed sum of money for the entire defense representation no matter whether it goes to trial or ends in a plea deal. I see cases all the time where a lawyer accepts a major felony case for a ridiculously low flat-fee just to land the client. Then, when it becomes obvious the case will require a lot of work, the attorney hits the client up for more money. I have even seen cases where the attorney threatens to withdraw from the case if the client does not come up with the additional funds. I call these “pump and dumps:” The lawyer pumps the client for a quick cash infusion and if the client balks, the lawyer tries to dump the client or the retainer agreement. When this happens, the client rightfully becomes upset and the situation quickly becomes untenable. What should a client do? They have (or should have) a written and enforceable fee agreement with the attorney. Then again, who wants a lawyer defending them from serious criminal charges when they claim they are being paid for their work? Defending clients charged with serious or complex felony cases in state and federal courts takes a great amount of work on the part of the criminal defense attorney, the client, and the defense team. These cases are expensive. To get an idea of how expensive, ask the attorney what their normal hourly fee is. The ask them how many hours they would expect to work in a case such as yours. What if it is a plea? What if it is a trial? If the lawyer’s retainer agreement sounds too good to be true, it probably is. The best thing a person can do when selecting a criminal defense attorney is to deal very clearly with this issue up-front. Hourly fee agreements will avoid the problem altogether. The attorney is paid only for the work performed. When negotiating an hourly fee agreement with a criminal defense attorney, be sure to ask the attorney to give a good faith estimate of the number of hours she or he thinks the case will consume depending on various outcomes like a plea agreement or a trial. If you are negotiating a flat-flee agreement make sure that both parties understand that regardless of how many hours the attorney must spend on the case, the fee agreement spells out the total amount to be paid in attorney fees. To protect both parties, flat fee agreements can be modified to suit the needs of each case. For example: The amount of the fee could be staggered to depend on at what stage of the proceedings the case is resolved: Pre-Indictment, with a plea agreement, after a trial etc. Regardless of the attorney and the fee structure you choose. I always recommend the potential client talk to as many knowledgeable and experienced criminal defense attorneys as the situation allows before settling on their pick. This will give the prospective client some idea of comparable fee agreements and rates. It will also allow both parties to get to know each other a little bit before signing up to work so closely together over so serious a matter. Switching attorneys in the middle of the case is sometimes unavoidable, but it is a situation best-avoided if possible.

In federal cases, Congress not only defines what is a crime that can cost the accused both freedom and property, but it also passes statutes that control how federal judges are allowed to sentence those who have been convicted of federal drug crimes. For instance, federal judges must follow the United States Sentencing Guidelines when sentencing someone upon conviction of a federal crime. For more on sentencing guidelines and how they work, read our discussion in Federal Sentencing Guidelines: Conspiracy To Distribute Controlled Substance Cases.

Sometimes, Congress sets a bottom line on the number of years someone must spend behind bars upon conviction for a specific federal crime. The federal judge in these situations has no discretion: he or she must follow the Congressional mandate.

Of course, there are a tremendous number of federal laws that define federal drug crimes. For purposes of illustration, consider those federal drug crimes that come with either (1) a sentence of 10 years to life imprisonment or (2) those that come with a sentence of 5 to 40 years behind bars, both defined as the mandatory sentences to be given upon conviction for these defined federal drug crimes.

For reference, these refer to the statutory language of 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A) and 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B), which instruct the federal judge on how he or she shall sentence anyone convicted of the manufacture, distribution, or dispensing of a controlled substance (i.e., an illegal drug) or possession with intent to either of these things.

Key here: the judge is given the mandatory minimum number of years that the accused must spend behind bars by Congress via the federal statutory language. A federal judge cannot go below ten (10) years for a federal drug crime based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A). He or she cannot go below five (5) years for a federal drug crime conviction based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B).

Can’t there be any way to get around that set-in-stone bottom line? Yes. There is also a statutory exception which allows the federal judge to dip below that mandatory minimum number of years in some situations. It is called the “Safety Valve” defense.

The law, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), provides for an exception that allows the federal judge some leeway in drug crime convictions where he or she would otherwise be required to follow the mandatory minimum sentencing statute. This is the Safety Value statute. It states as follows:

(f)Limitation on Applicability of Statutory Minimums in Certain Cases.—Notwithstanding anyother provision of law, in the case of an offense under section 401, 404, or 406 of theControlled Substances Act(21 U.S.C. 841, 844, 846), section 1010 or 1013 of theControlled Substances Import and Export Act(21 U.S.C. 960, 963), or section 70503 or 70506 of title 46, the court shall impose a sentence pursuant to guidelines promulgated by the United States Sentencing Commission undersection 994 of title 28without regard to any statutory minimum sentence, if the court finds at sentencing, after the Government has been afforded the opportunity to make a recommendation, that—

(A)more than 4 criminal history points, excluding any criminal history points resulting from a 1-point offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines;

(4)the defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor of others in the offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in section 408 of theControlled Substances Act; and

(5)not later than the time of the sentencing hearing, the defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

Information disclosed by a defendant under this subsection may not be used to enhance the sentence of the defendant unless the information relates to aviolent offense.

The only way to allow for this exception to be applied in a federal sentencing hearing is for the defense to argue its application and to provide authenticated and admissible support for use of the Safety Valve.

How does the defense do this? It takes much more than referencing the exception to the general rule itself. The defense will have to demonstrate the convicted defendant meets the Safety Valve’s five (5) requirements.

Federal sentencing has its own reference manual that is used throughout the United States, called the United States Sentencing Guidelines (“USSG”). We have gone into detail about the USSG and its applications in earlier discussions; to learn more, read:

In short, the idea is that the USSG work to keep things fair for people being sentenced in federal courts no matter which state they are located. Someone convicted in Texas, for instance, should be able to receive the same or similar treatment in a federal sentencing hearing as someone in Alaska, Maine, or Hawaii.

Part of how the Sentencing Guidelines work is by assessing “points.” Offenses are given points. The points tally into a score that is calculated according to the USSG.

Essentially, the accused can be charged with a three-point offense; a two-point offense; or a one-point offense. The number of points will depend on things like if it is a violent crime; violent crimes get more points than non-violent ones. The higher the overall number of points, and the ultimate total score, then the longer the sentence to be given under the USSG.

For a successful safety valve defense, the defense has to show that the total Criminal History Points are four (4) or less. If you have a maximum of four Criminal History points, you have met the first criteria for the safety valve.

Note: prior to the passage of the First Step Act, things were much harsher. If the defense had even two Criminal History Points, then the accused was ineligible for the safety valve. The First Step Act increased the number of points, or score, from one to four as the maximum allowed for application of the safety valve. For more on the First Step Act, see The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 1 of 2 and The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 2 of 2.

Looking at the Safety Valve statute ( 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)), the second step in achieving application of the safety valve defense involves the circumstances of the underlying criminal activity and whether or not it involved violence of threats or violence, or if the defendant possessed a firearm at the time.

It has been my experience that it is pretty common for there to be a firearm of some sort involved in a federal drug crime prosecution. Here, the impact of Texas being a part of the Fifth Judicial District for the United States Court of Appeals (“Fifth Circuit”) is important.

This is because this overseeing federal appeals court has looked at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and its definition of possession of a firearm, and come to a different conclusion that the definition given in the USSG.

Meanwhile, the Fifth Circuit has ruled that under the Safety Valve Statute, the standard for the government is much higher. According to their ruling, in order to be disqualified from application of the safety valve because of possession of a firearm, the defendant has to have been actually in possession of the firearm or in construction possession of it. See, US v. Wilson, 105 F.3d 219 (5th Cir. 1997).

Consider how this works in a federal drug crime conspiracy case. Under the USSG, a defendant can receive two (2) points (“enhancement”) for possession of a firearm even if they never had their hands on the gun. As long as a co-conspirator (co-defendant) did have possession of it, and that possession was foreseeable by the defendant, then the Sentencing Guidelines allow for a harsher sentence (more points).

The position of the Fifth Circuit looks upon this situation and determines that it is one thing for the defendant to have possession of the firearm, and another for there to be stretching things to cover constructive possession when he or she never really had the gun.

This is the example of the importance of effective criminal defense representation, where research reveals that it is easier to achieve a safety valve defense with a reference to case law. The Fifth Circuit allows a situation where someone can get two (2) points under the USSG (“enhancement”) and still be eligible for the safety valve defense.

The commentary to § 5C1.2(2) provides that “[c]onsistent with [U.S.S.G.] § 1B1.3 (Relevant Conduct),” the use of the term “defendant” in § 5C1.2(2) “limits the accountability of the defendant to his own conduct and conduct that he aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused.” See U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, comment. (n.4). This language mirrors § 1B1.3(a)(1)(A). Of import is the fact that this language omits the text of § 1B1.3(a)(1)(B) which provides that “relevant conduct” encompasses acts and omissions undertaken in a “jointly undertaken criminal activity,” e.g. a conspiracy.

Being bound by this commentary, we conclude that in determining a defendant’s eligibility for the safety valve, § 5C1.2(2) allows for consideration of only the defendant’s conduct, not the conduct of his co-conspirators. As it was Wilson’s co-conspirator, and not Wilson himself, who possessed the gun in the conspiracy,the district court erred in concluding that Wilson was ineligible to receive the benefit of § 5C1.2. Because application of § 5C1.2 is mandatory, see U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2 (providing that the court “shall” impose a sentencing without regard to the statutory minimum sentence if the defendant satisfies the provision’s criteria), we vacate Wilson’s sentence and remand for resentencing.

The defense must also be able to prove that the defendant’s role in the underlying criminal offense did not result in the death or bodily injury of someone else to achieve the safety valve defense under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In drug cases, this can mean more than some type of violent scenario. The mere type of drug or controlled substance involved can impact the success of this defense. Sometimes, the drugs themselves are the type that can cause severe harm or death. Several controlled substances can be lethal. In a federal drug case, there is a special definition for death resulting from the distribution of a controlled substance.

If the defense can prove with authenticated and admissible evidence that the defendant did not distribute a drug or controlled substance that ended up with someone’s death, or severe bodily injury, then the safety valve defense will be available to them.

Role adjustments happen when someone is alleged to be involved in a conspiracy, and they act in some type of position of responsibility. They can be a leader, or organizer, or somebody who supervises other people in the operations, all as defined in the USSG.

If you are to achieve the safety valve defense, you cannot receive any “role adjustment” under the Sentencing Guidelines. This must be established to the court by your defense attorney at the sentencing.

The defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

I realize that for many people, this language brings with it the assumption that the defendant has to be a snitch in order to meet this requirement for the safety valve defense. This is not true.

This law does not require a defendant to cooperate against other people in a conspiracy, be it friends or family members or anyone else. It does not force a defendant to turn over new or additional evidence to the police or prosecutors so the government can use it against other defendants. It does not mean the defendant has to cooperate with the government to help them go after unindicted co-conspirators, either.

With an experienced criminal defense lawyer, what it does mean is that the defendant has a meeting with the authorities with the goal of meeting the Safety Valve Statute requirements and no more.

The attorney can limit the scope of the meeting. He or she can make sure that law enforcement follows the rules for the meeting. The meeting is necessary for the defendant to achieve a safety valve defense, so there is no way to avoid a safety valve interview.

To get the sentence that is below the mandatory minimum sentence, the meeting is a must. However, it is not a free-for-all for the government where the defendant is ratting on other people.

One example involves a case where I represented a client before the federal district court in Corpus Christi, the United States District Court for the Southern District of Texas. He was among several co-defendants charged in a conspiracy to distribute methamphetamine.

I arranged for my client to have his safety valve meeting as well as establishing the other criteria needed for application of the Safety Valve statute. I was present at the meeting. There was no cooperation regarding the other defendants, and he did nothing more than the minimum to qualify for the defense. He was no snitch.

As a result, the safety valve was applied by the federal judge and my client achieved a safety valve application where he was sentenced to 8 years for distribution of meth: well below the 10 years of the mandatory minimums and the USSG calculation in his case of around 14 years.

Sadly, the same day that my client was sentenced, so were several of the co-conspirator defendants. I was aware that they were also eligible for the safety valve defense. However, the federal agent at the sentencing hearings that day told me that their lawyers never contact the government for a safety valve meeting.

They were never debriefed, so they could not meet the requirements for application of the safety value statute. The judge had no choice –they each had to be sentenced to the mandatory minimum sentences under the law.

Proposed in March 2013, the Justice Safety Valve Act would allow federal judges to hand down sentences below current mandatory minimums if: The mandatory minimum sentence would not accomplish the goal that a sentence be sufficient, but not greater than necessary

The factors the judged considered in arriving at the lower sentence are put in writing and must be based on the language is based on the language of 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a)

This proposed updated safety valve would apply to any federal conviction that has been prescribed a mandatory minimum sentence. As written, it would not apply retroactively; inmates already serving a mandatory minimum sentence would not be allowed to request a lesser sentence or re-sentencing based on the Act. It would only apply to federal sentencing; North Carolina would have to enact its own legislation to change state mandatory minimum sentencing.

In 2012, there were 219,000 inmates being held in federal institutions run by the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP). In 1980, there were only 25,000. Approximately one-quarter of the Justice Department’s budget is spent on corrections. Over 10,000 people received federal mandatory minimum sentences in 2010.

In addition to these statistics, the application of mandatory minimum sentences leads to absurdly long sentences being imposed, at great taxpayer expense, on non-violent individuals. The organization Families Against Mandatory Minimums (FAMM) details how mandatory minimums have resulted in substantial – and unfair – punishments for low-level crimes, including these two examples: Weldon Angelos: Mr. Angelos was sentenced to 55 years in prison after making several small drug sales to a government informant. Several weapons were found in his home and the informant reported seeing a weapon in Mr. Angelos’ possession during at least two buys. He was charged with several counts of possessing a gun during a drug trafficking offense, leading to the substantial sentence, despite having no major criminal record, dealing only in small amounts of weed, and never using a weapon during the course of a drug transaction.

John Hise: Mr. Hise was sentenced to 10 years on a drug conspiracy charge. He had sold red phosphorous to a friend who was involved in meth manufacturing. Mr. Hise stopped aiding his friend, but not before authorities had caught on. He was convicted and sentenced to 10 years despite police finding no evidence of red phosphorous in his home during a search. Mr. Hise was ineligible for the current safety valve law because of a possession and DUI offense already on his record.

The use of mandatory minimums that allow little discretion for judges to depart to a lower sentence have contributed to the growing prison population and expense of housing those arbitrarily required to spend years in prison. There is certainly room for improvement. Expanding this safety valve to all mandatory minimum sentences would reduce the long-term prison population while still ensuring that the goals of sentencing are met.

The first question a federal judge must consider in deciding whether or not he or she will sentence a person convicted of a federal offense below the mandatory minimum under the proposed Act is whether the mandatory minimum sentence would over punish that person. In other words, would the mandatory minimum put the person in prison for longer than is necessary to meet the goals of sentencing?

The proposed Act would ensure that the goals of sentencing return to the forefront of determining an appropriate prison term rather than substituting the judgment of Congress for that of the presiding judge during the sentencing phase of the federal criminal process.

There are currently just under 200 mandatory minimum sentences for federal crimes on the books, but only federal drug offenses are subject to an existing sentencing safety valve. The actual text of the existing sentencing safety valve can be found at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In order for a federal judge to apply the existing safety valve to sentencing for a federal drug crime, he or she must make the following findings: No one was injured during the commission of the drug offense

These criteria are strict and minimize the number of people who could be saved from lengthy, arbitrary prison sentences. The legal possession of a gun during the commission of a drug crime has been used to deny the application of the safety valve as has prior criminal history that included only misdemeanor or petty offenses. In effect, the current safety valve legislation allows only about one-quarter of those sentenced on federal drug offenses to take advantage of the deviation from mandatory minimums each year.

Another exception to mandatory minimum sentencing, substantial assistance, is often unavailable to low-level drug offenders. Often those who are tasked with transporting or selling drugs, or who are considered mules, have little if any information about the actual drug ring itself. These people are then not eligible for a reduced sentence below a mandatory minimum because they have no information to provide prosecutors; they are incapable of providing substantial assistance.

Identical versions of the Act were introduced in the House and Senate, H.R. 1695 and S. 619. Both have been referred to the committee for review. The proposed Safety Valve Act would expand the application of the safety valve beyond drug crimes and would allow judges to ensure that sentencing goals are met while not over-punishing individuals and overcrowding the nation’s prison system.

However, the Safety Valve Act is no substitute for an experienced federal defense lawyer on the side of anyone facing federal charges; it is not a get out of jail card. If a judge deviates below mandatory minimums in sentencing, he or she would still be required to apply the federal sentencing guidelines in determining an appropriate sentence.

This informational article about the proposed Justice Safety Valve Act is provided by the attorneys of Roberts Law Group, PLLC, a criminal defense law firm dedicated to the rights of those accused of a crime throughout North Carolina. To learn more about the firm, please like us on Facebook; follow us on Twitter or Google+ to get the latest updates on safety and criminal defense matters in North Carolina. For a free consultation with a Charlotte defense lawyer from Roberts Law Group, please call contact our law firm online.

In this case, our client was charged with First Degree Murder in connection with a “drive-by” shooting that occurred in Charlotte, NC. The State’s evidence included GPS ankle monitoring data linking our client was at the scene of the crime and evidence that our client confessed to an inmate while in jail. Nonetheless, we convinced a jury to unanimously find our client Not Guilty. He was released from jail the same day.

Our client was charged with First Degree for the shooting death related to alleged breaking and entering. The State’s evidence included a co-defendant alleging that our client was the shooter. After conducting a thorough investigation with the use of a private investigator, we persuaded the State to dismiss entirely the case against our client.

After conducting an investigation and communicating with the prosecutor about the facts and circumstances indicating that our client acted in self-defense, the case was dismissed and deemed a justifiable homicide.

Our client was charged with the First Degree Murder of a young lady by drug overdose. After investigating the decedent’s background and hiring a preeminent expert toxicologist to fight the State’s theory of death, we were able to negotiate this case down from Life in prison to 5 years in prison, with credit for time served.

Our client was charged with First Degree Murder related to a “drug deal gone bad.” After engaging the services of a private investigator and noting issues with the State’s case, we were able to negotiate a plea for our client that avoided a Life sentence and required him to serve only 12 years.

Imagine this scenario: Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents bust a small-time drug dealer for, let’s say, nickel-and-diming in heroin. They take him to booking, run his fingerprints and discover this is his third arrest. As a multiple offender facing a long stretch in prison and with a public defender at his side, the suspect offers a deal.

The lead agent and his partner glance at each other. Here it is: a chance to nail the slippery kingpin who runs a multi-million dollar heroin ring that covers three states, but who has somehow managed to elude capture again and again. Never mind that coincidentally their case-closure rate will skyrocket, making them look good. There is a brief pause as the lead agent again glances at his partner, then back at our suspect.

You might think so, and you’d be right. But in the daily trenches of law enforcement, this scenario is not as far-fetched as it appears. In fact, wheeling and dealing is more of a way of life than many police officers and prosecutors care to openly admit. It is, quite simply, the practice of using snitches to obtain convictions. [See: PLN, June 2010, p.1; Feb. 2006, p.28].

But wait, you say. What about the old saying, “snitches get stitches?” Don’t rats end up at the bottom of the nearest river? If that’s true, then the river bottom is a very crowded place.

Nationwide, court records indicate that 25% of offenders sent to federal prison for drug-related crimes provided information to prosecutors in exchange for shorter sentences. In some jurisdictions, like Idaho, Colorado and the Eastern District of Kentucky, more than half did. Sometimes these sentence reductions can amount to 50% or more, according to the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

Given that incentive, it’s inevitable that some prisoners would find a way to profit from such a dysfunctional system. According to a 2012 USA Today investigation that examined hundreds of thousands of court cases, “snitching has become so commonplace that in the past five years at least 48,895 federal convicts – one out of every eight – had their prison sentences reduced in exchange for helping government investigators....”

Citizens who live their lives happily ignorant of the criminal justice system are unaware that it is a closed loop, starting at the top. Judges, many of whom are former prosecutors and who draw their paychecks from the same government that pays the police and prosecution, are generally hesitant to cast doubt on the legitimacy of their brethren’s crime-fighting methods. Further, judge-made case law over the years has upheld the right of the police to use almost any tactic to solve crimes, including lying and the use of informants.

As a result, prosecutors at both the state and federal levels face few checks upon their power. Knowing that jurors fear crime and seek safer neighborhoods, U.S. Attorneys and their local district attorney counterparts gather information to use as evidence in criminal cases from whomever they can, including prisoners seeking to shorten their sentences.

The incarcerated – and the people who guard them – know there are few secrets in jail or prison. People talk about everything, including their cases. The more canny and opportunistic prisoners realize from first-hand experience that prosecutors “pay” well with sentence reductions for information on someone they have insufficient evidence to convict.

To the naïve or uninitiated, law enforcement, in its battle against crime, should be able to use every tool at its disposal. If that means relying on testimony from one criminal to convict another, so be it. Except in the most obvious cases of prosecutorial overreach, juries hold their collective noses and vote guilty, ignoring misgivings about the source of the incriminating “proof” or the motives of the jailhouse snitch who takes the stand against a defendant.

However, the USA Today investigation that examined the culture of snitching questioned the usefulness of such testimony and cast doubt on whether it serves the ends of justice.

Justice, in its purest form, relies on truth – but within the snitching community, truth is a rare commodity and can be the first casualty in a system that seems more interested in obtaining convictions than dispensing justice. Prosecutors eager to close a case often reward criminals with sentence reductions for inaccurate, manufactured or questionable “evidence” or testimony against another offender.

The case of federal prisoner Marcus Watkins is one example of the unintended consequences of the institutionalized culture of snitching. According to USA Today, “For a fee, [Watkins] and his associates on the outside sold ... information about other criminals that they could turn around and offer up to federal agents in hopes of shaving years off their prison sentences.”

Watkins’ case is not the only one of its kind, but certainly one of the most documented. His outside associates collected and offered to sell information about the drug trade to fellow prisoners at the Atlanta City Detention Center, most of whom had the money, and incentive, to pay for it. And they were not the only customers; according to Watkins, “the biggest buyer of information is the government.” Only the currency was different. “They pay in years,” Watkins said, claiming that federal agents he spoke with “knew money’s been changing hands. They basically authorized all of this.”

Robert McBurney, a former federal prosecutor from Atlanta, called it “a pernicious situation that sadly, undid some good works,” but FBI agent Mile Brosas testified under oath that agents acted “just based on the names that Mr. Watkins gave us.” At the time Watkins provided the information and names referred to by Brosas, he had already been behind bars for some time. Therefore, the logical assumption would have been that he was receiving his information from outside the prison – though that did not deter the prosecutors who relied on that information in other criminal cases.

The court was not amused. The then-chief judge of the federal district court in Atlanta, Judge Julie E. Carnes, decried the “abominable situation” of such information peddling, stating she was “appalled that it’s going on to the level it appears to be going on.”

And Watkins’ case is clearly not an isolated example. As noted by Professor Tim Saviello at the John Marshall Law School in Chicago, “People are willing to pay $20,000 or $30,000 to get a piece of information. That tells you how valuable it is.”

The pressure to snitch is overwhelming. Suspects accused of federal crimes almost always accept plea bargains. Those who don’t are generally convicted at trial, and the lengthier sentences they typically receive for refusing to plead guilty are known as the “trial penalty.” For someone in such a position, who may be facing a mandatory minimum prison term of 10 to 20 years, informing on fellow criminals is their only chance at leniency.

The fact remains that most prisoners serving time for drug offenses are not major players in the drug trade. In 1995, the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that only 11% of federal drug trafficking defendants were major traffickers; the rest were lower-level offenders. Even “safety-valve” modifications to the mandatory minimum sentencing guidelines did little to reduce the explosion in the number of prisoners convicted of drug crimes. Such offenders are under pressure to offer “substantial assistance” to the government, often in the form of information about other drug dealers, as a means of obtaining sentencing relief. During the past five years, fully one-third of drug traffickers sentenced in federal court received sentence reductions for providing “substantial assistance.”

Drug conspiracy laws enacted in 1988 also contributed to the influx of federal drug offenders, allowing the government to win convictions for what prisoners often term “ghost drugs,” by swearing that any information provided was about a suspect who was part of the snitch’s drug ring. Unfortunately, such a system can snare innocent bystanders – defendants who become the victims of lies told by their codefendants who have figured out how to manipulate the sentencing laws in order to reduce their own prison terms.

One of the most egregious examples of misuse of the justice system by both police and prosecutors occurred in Louisiana, where the Colomb family suffered years of prosecution, imprisonment and economic disaster that began with a minor drug possession charge against the teenaged son of Ann Colomb, the family matriarch. According to court filings, prosecutors claimed that Colomb and her sons, living on a mostly black street in a white section of the town of Church Point, Louisiana, ran a $70 million drug operation.

The trouble started when two of Colomb’s sons, Sammie and Edward, pleaded no contest to felony possession and received probation. Church Point, like many southern towns, suffered from documented racial tensions, heightened by the fact that another Colomb son, Danny, dated a white woman. According to Rodney Baum, the Colomb family lawyer, “They took a bunch of unrelated police harassments of these people over 10 years, coupled it with a parade of jailhouse snitches.... It was ridiculous.” The federal prosecutor, U.S. Attorney Bret Grayson, used more than 30 imprisoned informants to compile his evidence of a drug conspiracy.

As the case neared trial, U.S. District Court Judge Tucker Melancon began having misgivings and sought to bar many of the informants from testifying. The case, despite being already weakened by a lack of hard evidence and the fact that Colomb family members had continued to work construction and oilfield jobs while supposedly netting millions in the illicit drug trade, moved forward. The jury convicted the family in 2006 and they went to prison.

Then another convicted federal prisoner, Quinn Alex, in a letter to his former prosecutor, revealed the scope and details of a snitching-for-hire scheme at the Federal Correctional Institution in Three Rivers, Texas, the source of the information used by U.S. Attorney Grayson in the Colomb case. A motion for a new trial soon followed, and Judge Melancon vacated the convictions and freed the family.

The Colombs were “fortunate,” as they were released from prison and justice prevailed. But under any definition of justice they shouldn’t have been convicted in the first place, and the case vividly demonstrated the unintended consequences of the snitching industry that is firmly entrenched in the U.S. justice system. Ann Colomb expressed it best: “What happened to us should never happen to anyone. It breaks my heart....”

But the real victim is justice itself, in the form of wrongful convictions, official corruption, public deception and the weakened legitimacy of the criminal justice system in the eyes of the public. The use of snitches has become so prevalent that the practice and its damaging effects are the subject of a book, Snitching: Criminal Informants and the Erosion of American Justice, by Alexandra Natapoff, published in April 2011.

Under such scrutiny the practice of snitching, spurred by harsh sentencing laws and win-at-any-cost prosecutors, might gradually fade. Snitching has already faced a backlash due to a controversial DVD series called “Stop Snitching,” created by Ronnie Thomas, a Baltimore resident also known as Skinny Suge. The first video was released in 2004 and a sequel followed in 2007; Baltimore police have called the DVDs a form of witness intimidation.

Suge is now serving a 19-year federal prison term. In an ironic twist of fate, his 14-year-old son, Najee Thomas, was murdered in April 2014, shot in the head as he sat inside his home in the Cherry Hill section of Baltimore. Police have not said whether Najee’s death was related to his father’s violent past, but blame the DVDs for a declining case-closure rate. They say the “Stop Snitching” videos have created an increasing unwillingness by members of the public to come forward with crime tips.

Perhaps a TV crime drama might not be the best setting for a discussion of the culture of snitching in our nation’s criminal justice system. A more appropriate venue might be a game show – for example, “Let’s Make a Deal.”

Commission, 2012 Federal Sentencing Statistics. http://www.ussc.gov/Data_and_Statistics/Federal_Sentencing_Statistics/State_District_Circuit/2012/index.cfm

A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). They do not repeal or eliminate mandatory minimum sentences. However, safety valves save taxpayers money because they allow courts to give shorter, more appropriate prison sentences to offenders who pose less of a public safety threat. This saves our scarce taxpayer dollars and prison beds for those who are most deserving of the mandatory minimum term and present the biggest danger to society.

The Problem:Under current federal law, there is only one safety valve, and it applies only to first-time, nonviolent drug offenders whose cases did not involve guns. FAMM was instrumental in the passage of this safety valve, in 1994. Since then, more than 95,000 nonviolent drug offenders have received fairer sentences because of it, saving taxpayers billions. But it is a very narrow exception: in FY 2015, only 13 percent of all drug offenders qualified for the exception.

Mere presence of even a lawfully purchased and registered gun in a person’s home or car is enough to disqualify a nonviolent drug offender from the safety valve,

Even very minor prior infractions (e.g., careless driving) that resulted in no prison time can disqualify an otherwise worthy low-level drug offender from the safety valve, and

Other federal mandatory minimum sentences for other types of crimes – notably, gun possession offenses – are often excessive and apply to low-level offenders who could serve less time in prison, at lower costs to taxpayers, without endangering the public.

The Solution:Create a broader safety valve that applies to all mandatory minimum sentences, and expand the existing drug safety valve to cover more low-level offenders.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

8613371530291

8613371530291