the safety valve discharges automatically at the pressure of factory

Finding a quality driving school in can be a difficult and time consuming task. driving-schools.com comprehensive database of driving schools helps you pick one that’s right for you.

With a basically fully-charged air system (within the effective operating range for the compressor), turn off the engine, release all brakes, and let the system settle (air gauge needle stops moving). Time for 1 minute. The air pressure should not drop more than:

An overpressure event refers to any condition which would cause pressure in a vessel or system to increase beyond the specified design pressure or maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP).

Many electronic, pneumatic and hydraulic systems exist today to control fluid system variables, such as pressure, temperature and flow. Each of these systems requires a power source of some type, such as electricity or compressed air in order to operate. A pressure Relief Valve must be capable of operating at all times, especially during a period of power failure when system controls are nonfunctional. The sole source of power for the pressure Relief Valve, therefore, is the process fluid.

Once a condition occurs that causes the pressure in a system or vessel to increase to a dangerous level, the pressure Relief Valve may be the only device remaining to prevent a catastrophic failure. Since reliability is directly related to the complexity of the device, it is important that the design of the pressure Relief Valve be as simple as possible.

The pressure Relief Valve must open at a predetermined set pressure, flow a rated capacity at a specified overpressure, and close when the system pressure has returned to a safe level. Pressure Relief Valves must be designed with materials compatible with many process fluids from simple air and water to the most corrosive media. They must also be designed to operate in a consistently smooth and stable manner on a variety of fluids and fluid phases.

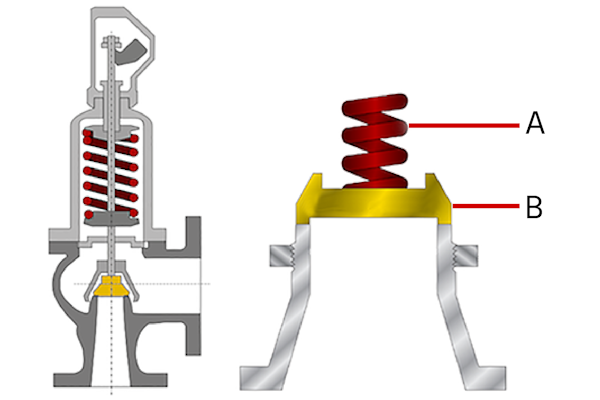

The basic spring loaded pressure Relief Valve has been developed to meet the need for a simple, reliable, system actuated device to provide overpressure protection.

The Valve consists of a Valve inlet or nozzle mounted on the pressurized system, a disc held against the nozzle to prevent flow under normal system operating conditions, a spring to hold the disc closed, and a body/Bonnet to contain the operating elements. The spring load is adjustable to vary the pressure at which the Valve will open.

When a pressure Relief Valve begins to lift, the spring force increases. Thus system pressure must increase if lift is to continue. For this reason pressure Relief Valves are allowed an overpressure allowance to reach full lift. This allowable overpressure is generally 10% for Valves on unfired systems. This margin is relatively small and some means must be provided to assist in the lift effort.

Most pressure Relief Valves, therefore, have a secondary control chamber or huddling chamber to enhance lift. As the disc begins to lift, fluid enters the control chamber exposing a larger area of the disc to system pressure.

This causes an incremental change in force which overcompensates for the increase in spring force and causes the Valve to open at a rapid rate. At the same time, the direction of the fluid flow is reversed and the momentum effect resulting from the change in flow direction further enhances lift. These effects combine to allow the Valve to achieve maximum lift and maximum flow within the allowable overpressure limits. Because of the larger disc area exposed to system pressure after the Valve achieves lift, the Valve will not close until system pressure has been reduced to some level below the set pressure. The design of the control chamber determines where the closing point will occur.

When superimposed back pressure is variable, a balanced bellows or balanced piston design is recommended. A typical balanced bellow is shown on the right. The bellows or piston is designed with an effective pressure area equal to the seat area of the disc. The Bonnet is vented to ensure that the pressure area of the bellows or piston will always be exposed to atmospheric pressure and to provide a telltale sign should the bellows or piston begin to leak. Variations in back pressure, therefore, will have no effect on set pressure. Back pressure may, however, affect flow.

A safety Valve is a pressure Relief Valve actuated by inlet static pressure and characterized by rapid opening or pop action. (It is normally used for steam and air services.)

A low-lift safety Valve is a safety Valve in which the disc lifts automatically such that the actual discharge area is determined by the position of the disc.

A full-lift safety Valve is a safety Valve in which the disc lifts automatically such that the actual discharge area is not determined by the position of the disc.

A Relief Valve is a pressure relief device actuated by inlet static pressure having a gradual lift generally proportional to the increase in pressure over opening pressure. It may be provided with an enclosed spring housing suitable for closed discharge system application and is primarily used for liquid service.

A safety Relief Valve is a pressure Relief Valve characterized by rapid opening or pop action, or by opening in proportion to the increase in pressure over the opening pressure, depending on the application and may be used either for liquid or compressible fluid.

A conventional safety Relief Valve is a pressure Relief Valve which has its spring housing vented to the discharge side of the Valve. The operational characteristics (opening pressure, closing pressure, and relieving capacity) are directly affected by changes of the back pressure on the Valve.

A balanced safety Relief Valve is a pressure Relief Valve which incorporates means of minimizing the effect of back pressure on the operational characteristics (opening pressure, closing pressure, and relieving capacity).

A pilotoperated pressure Relief Valve is a pressure Relief Valve in which the major relieving device is combined with and is controlled by a self-actuated auxiliary pressure Relief Valve.

A poweractuated pressure Relief Valve is a pressure Relief Valve in which the major relieving device is combined with and controlled by a device requiring an external source of energy.

A temperature-actuated pressure Relief Valve is a pressure Relief Valve which may be actuated by external or internal temperature or by pressure on the inlet side.

A vacuum Relief Valve is a pressure relief device designed to admit fluid to prevent an excessive internal vacuum; it is designed to reclose and prevent further flow of fluid after normal conditions have been restored.

Many Codes and Standards are published throughout the world which address the design and application of pressure Relief Valves. The most widely used and recognized of these is the ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code, commonly called the ASME Code.

Most Codes and Standards are voluntary, which means that they are available for use by manufacturers and users and may be written into purchasing and construction specifications. The ASME Code is unique in the United States and Canada, having been adopted by the majority of state and provincial legislatures and mandated by law.

The ASME Code provides rules for the design and construction of pressure vessels. Various sections of the Code cover fired vessels, nuclear vessels, unfired vessels and additional subjects, such as welding and nondestructive examination. Vessels manufactured in accordance with the ASME Code are required to have overpressure protection. The type and design of allowable overpressure protection devices is spelled out in detail in the Code.

The following definitions are taken from DIN 3320 but it should be noted that many of the terms and associated definitions used are universal and appear in many other standards. Where commonly used terms are not defined in DIN 3320 then ASME PTC25.3 has been used as the source of reference. This list is not exhaustive and is intended as a guide only; it should not be used in place of the relevant current issue standard..

is the gauge pressure at which the lift is sufficient to discharge the predetermined flowing capacity. It is equal to the set pressure plus opening pressure difference.

is the cross sectional area upstream or downstream of the body seat calculated from the minimum diameter which is used to calculate the flow capacity without any deduction for obstructions.

is the calculated mass flow from an orifice having a cross sectional area equal to the flow area of the safety Valve without regard to flow losses of the Valve.

the pressure at which a Valve is set on a test rig using a test fluid at ambient temperature. This test pressure includes corrections for service conditions e.g. backpressure or high temperatures.

is that portion of the measured relieving capacity permitted by the applicable code or regulation to be used as a basis for the application of a pressure relieving device.

is the value of increasing static inlet pressure of a pressure Relief Valve at which there is a measurable lift, or at which the discharge becomes continuous as determined by seeing, feeling or hearing.

is the maximum allowable working pressure plus the accumulation as established by reference to the applicable codes for operating or fire contingencies.

Because cleanliness is essential to the satisfactory operation and tightness of a safety Valve, precautions should be taken during storage to keep out all foreign materials. Inlet and outlet protectors should remain in place until the Valve is ready to be installed in the system. Take care to keep the Valve inlet absolutely clean. It is recommended that the Valve be stored indoors in the original shipping container away from dirt and other forms of contamination.

Safety Valves must be handled carefully and never subjected to shocks. Rough handling may alter the pressure setting, deform Valve parts and adversely affect seat tightness and Valve performance.

When it is necessary to use a hoist, the chain or sling should be placed around the Valve body and Bonnet in a manner that will insure that the Valve is in a vertical position to facilitate installation.

Many Valves are damaged when first placed in service because of failure to clean the connection properly when installed. Before installation, flange faces or threaded connections on both the Valve inlet and the vessel and/or line on which the Valve is mounted must be thoroughly cleaned of all dirt and foreign material.

Because foreign materials that pass into and through safety Valves can damage the Valve, the systems on which the Valves are tested and finally installed must also be inspected and cleaned. New systems in particular are prone to contain foreign objects that inadvertently get trapped during construction and will destroy the seating surface when the Valve opens. The system should be thoroughly cleaned before the safety Valve is installed.

The gaskets used must be dimensionally correct for the specific flanges. The inside diameters must fully clear the safety Valve inlet and outlet openings so that the gasket does not restrict flow.

For flanged Valves, draw down all connection studs or bolts evenly to avoid possible distortion of the Valve body. For threaded Valves, do not apply a wrench to the Valve body. Use the hex flats provided on the inlet bushing.

Safety Valves are intended to open and close within a narrow pressure range. Valve installations require accurate design both as to inlet and discharge piping. Refer to International, National and Industry Standards for guidelines.

The Valve should be mounted vertically in an upright position either directly on a nozzle from the pressure vessel or on a short connection fitting that provides a direct, unobstructed flow between the vessel and the Valve. Installing a safety Valve in other than this recommended position will adversely affect its operation.

Discharge piping should be simple and direct. A "broken" connection near the Valve outlet is preferred wherever possible. All discharge piping should be run as direct as is practicable to the point of final release for disposal. The Valve must discharge to a safe disposal area. Discharge piping must be drained properly to prevent the accumulation of liquids on the downstream side of the safety Valve.

The weight of the discharge piping should be carried by a separate support and be properly braced to withstand reactive thrust forces when the Valve relieves. The Valve should also be supported to withstand any swaying or system vibrations.

If the Valve is discharging into a pressurized system be sure the Valve is a "balanced" design. Pressure on the discharge of an "unbalanced" design will adversely affect the Valve performance and set pressure.

The Bonnets of balanced bellows safety Valves must always be vented to ensure proper functioning of the Valve and to provide a telltale in the event of a bellows failure. Do not plug these open vents. When the fluid is flammable, toxic or corrosive, the Bonnet vent should be piped to a safe location.

It is important to remember that a pressure Relief Valve is a safety device employed to protect pressure vessels or systems from catastrophic failure. With this in mind, the application of pressure Relief Valves should be assigned only to fully trained personnel and be in strict compliance with rules provided by the governing codes and standards.

A series of anomalies occurred in the boiler room that evening. The steel compression tank for the hydronic loop flooded, leaving no room for expansion. Water will expand at 3% of its volume when heated from room temperature to 180° F. When the burner fired, the expansion of the water increased the system pressure within the boiler. The malfunctioning operating control did not shut off the burner at the set point which caused the relief valve to open.

The brass relief valve discharge was installed with copper tubing piped solid to a 90° ell on the floor and the tubing further extended to the floor drain. The combination of hot water and steam from the boiler caused the discharge copper tubing to expand, using the relief valve as a fulcrum. The expansion of the copper discharge tubing pressing against the floor was enough to crack the brass relief valve, flooding the boiler room. The damage was not discovered until the next morning, several hours after the leak occurred. Thousands of dollars in damage was sustained and luckily no one was injured.

Each boiler requires some sort of pressure relieving device. They are referred to as either a safety, relief or safety relief valve. While these names are often thought of as interchangeable, there are subtle differences between them. According to the National Board of Boiler and Pressure Vessel Inspectors, the following are the definitions of each:

• Safety valve— This device is typically used for steam or vapor service. It operates automatically with a full-opening pop action and recloses when the pressure drops to a value consistent with the blowdown requirements prescribed by the applicable governing code or standard.

• Relief valve— This device is used for liquid service. It operates automatically by opening farther as the pressure increases beyond the initial opening pressure and recloses when the pressure drops below the opening pressure.

• Safety relief valve— This device includes the operating characteristics of both a safety valve and a relief valve and may be used in either application.

• Temperature and pressure safety relief valve— This device is typically used on potable water heaters. In addition to its pressure-relief function, it also includes a temperature-sensing element which causes the device to open at a predetermined temperature regardless of pressure. The set temperature on these devices is usually 210°.

• Relief valve piping— The boiler contractor installed a bushing on the outlet of the safety relief valve. Instead of 1 1/2-in. pipe, the installer used 3/4-in. pipe. When asked about it, he answered that he did not have any 1 1/2-in. pipe but had plenty of 3/4-in. pipe. I explained and then had to show the disbelieving contractor the code that states that the relief valve discharge piping has to be the same diameter as the relief valve outlet (see 2012 International Mechanical Code, 1006.6). By reducing the discharge pipe size, the relieving capacity of the safety valve may not be adequate to properly relieve the pressure inside the boiler, causing a dangerous situation.

The code also states that the discharge material shall be of rigid pipe that is approved for the temperature of the system. The inlet pipe size shall be full diameter of the pipe inlet for the relief valve. Some manufacturers suggest using black iron pipe rather than copper tubing. If using copper, it should have an air space that allows expansion should the relief valve open to avoid the accident that I referenced above. The discharge piping has to be supported and the weight of the piping should not be on the safety relief valve. Valves are not permitted in the inlet piping to or discharge piping from the relief valve. If you are using copper tubing on discharge piping, verify that there is room for expansion.

• Installation— Read the manufacturer’s installation manual as each may have different requirements. For instance, Conbraco requires that the discharge piping must terminate with a plain end and use a material that can handle temperatures of 375° or greater. This will preclude PVC or CPVC pipe for the discharge piping. The instruction manual for its model 12-14 steam relief valve stipulates that you cannot use a pipe wrench to install it. That would be good to know.

I once visited Boiler Utopia as the floor was clean and waxed. All the pipes were covered and exposed pipes were painted. There were large stickers detailing what was inside each pipe as well as directional arrows. Nothing was stacked next to the boilers. Yellow caution lines were painted on the floor around each boiler. I was in heaven. As I walked around the rear of the boiler, something clicked and triggered a warning bell. The discharge of the relief valve piping was about 6 in. from the floor but instead of a plain or angled cut end, the pipe had a threaded pipe cap on the termination. I asked the maintenance person about it and he said that the valve was leaking all over his newly waxed floor and this was the only way he could stop it. When I said that the discharge pipe should not have been threaded, he explained that it was not threaded and he had to take it to the local hardware store to thread it. I informed him that the cap had to be removed. We cut the pipe on an angle to prevent this.

• Steam boiler— Most manufacturers recommend a drip pan ell on the discharge of the steam boiler relief valve to eliminate the weight of the discharge piping on the relief valve. Some codes require the discharge to be vented outdoors.

• Testing— I will ask the attendees in my classes, “How often do you test the relief valves?” Most do not make eye contact and when I follow up with, “Why are they not tested?” I often hear that opening the relief valve will cause it to leak. I suggest that you refer to each manufacturer’s directions for testing. For instance, one will recommend once a year while another recommends twice a year. One manufacturer says, “Safety/relief valves should be operated only often enough to assure they are in good working order.” I am not sure what that even means. You want to also verify the proper test procedure as some will only want the relief valve tested when the boiler is at 75% of the rated pressure or higher of the relief valve.

There is a wide range of safety valves available to meet the many different applications and performance criteria demanded by different industries. Furthermore, national standards define many varying types of safety valve.

The ASME standard I and ASME standard VIII for boiler and pressure vessel applications and the ASME/ANSI PTC 25.3 standard for safety valves and relief valves provide the following definition. These standards set performance characteristics as well as defining the different types of safety valves that are used:

ASME I valve - A safety relief valve conforming to the requirements of Section I of the ASME pressure vessel code for boiler applications which will open within 3% overpressure and close within 4%. It will usually feature two blowdown rings, and is identified by a National Board ‘V’ stamp.

ASME VIII valve- A safety relief valve conforming to the requirements of Section VIII of the ASME pressure vessel code for pressure vessel applications which will open within 10% overpressure and close within 7%. Identified by a National Board ‘UV’ stamp.

Full bore safety valve - A safety valve having no protrusions in the bore, and wherein the valve lifts to an extent sufficient for the minimum area at any section, at or below the seat, to become the controlling orifice.

Conventional safety relief valve -The spring housing is vented to the discharge side, hence operational characteristics are directly affected by changes in the backpressure to the valve.

Balanced safety relief valve -A balanced valve incorporates a means of minimising the effect of backpressure on the operational characteristics of the valve.

Pilot operated pressure relief valve -The major relieving device is combined with, and is controlled by, a self-actuated auxiliary pressure relief device.

Power-actuated safety relief valve - A pressure relief valve in which the major pressure relieving device is combined with, and controlled by, a device requiring an external source of energy.

Standard safety valve - A valve which, following opening, reaches the degree of lift necessary for the mass flowrate to be discharged within a pressure rise of not more than 10%. (The valve is characterised by a pop type action and is sometimes known as high lift).

Full lift (Vollhub) safety valve -A safety valve which, after commencement of lift, opens rapidly within a 5% pressure rise up to the full lift as limited by the design. The amount of lift up to the rapid opening (proportional range) shall not be more than 20%.

Direct loaded safety valve -A safety valve in which the opening force underneath the valve disc is opposed by a closing force such as a spring or a weight.

Proportional safety valve - A safety valve which opens more or less steadily in relation to the increase in pressure. Sudden opening within a 10% lift range will not occur without pressure increase. Following opening within a pressure of not more than 10%, these safety valves achieve the lift necessary for the mass flow to be discharged.

Diaphragm safety valve -A direct loaded safety valve wherein linear moving and rotating elements and springs are protected against the effects of the fluid by a diaphragm

Bellows safety valve - A direct loaded safety valve wherein sliding and (partially or fully) rotating elements and springs are protected against the effects of the fluids by a bellows. The bellows may be of such a design that it compensates for influences of backpressure.

Controlled safety valve - Consists of a main valve and a control device. It also includes direct acting safety valves with supplementary loading in which, until the set pressure is reached, an additional force increases the closing force.

Safety valve - A safety valve which automatically, without the assistance of any energy other than that of the fluid concerned, discharges a quantity of the fluid so as to prevent a predetermined safe pressure being exceeded, and which is designed to re-close and prevent further flow of fluid after normal pressure conditions of service have been restored. Note; the valve can be characterised either by pop action (rapid opening) or by opening in proportion (not necessarily linear) to the increase in pressure over the set pressure.

Direct loaded safety valve -A safety valve in which the loading due to the fluid pressure underneath the valve disc is opposed only by a direct mechanical loading device such as a weight, lever and weight, or a spring.

Assisted safety valve -A safety valve which by means of a powered assistance mechanism, may additionally be lifted at a pressure lower than the set pressure and will, even in the event of a failure of the assistance mechanism, comply with all the requirements for safety valves given in the standard.

Supplementary loaded safety valve - A safety valve that has, until the pressure at the inlet to the safety valve reaches the set pressure, an additional force, which increases the sealing force.

Note; this additional force (supplementary load), which may be provided by means of an extraneous power source, is reliably released when the pressure at the inlet of the safety valve reaches the set pressure. The amount of supplementary loading is so arranged that if such supplementary loading is not released, the safety valve will attain its certified discharge capacity at a pressure not greater than 1.1 times the maximum allowable pressure of the equipment to be protected.

Pilot operated safety valve -A safety valve, the operation of which is initiated and controlled by the fluid discharged from a pilot valve, which is itself, a direct loaded safety valve subject to the requirement of the standard.

The common characteristic shared between the definitions of conventional safety valves in the different standards, is that their operational characteristics are affected by any backpressure in the discharge system. It is important to note that the total backpressure is generated from two components; superimposed backpressure and the built-up backpressure:

Subsequently, in a conventional safety valve, only the superimposed backpressure will affect the opening characteristic and set value, but the combined backpressure will alter the blowdown characteristic and re-seat value.

The ASME/ANSI standard makes the further classification that conventional valves have a spring housing that is vented to the discharge side of the valve. If the spring housing is vented to the atmosphere, any superimposed backpressure will still affect the operational characteristics. Thiscan be seen from Figure 9.2.1, which shows schematic diagrams of valves whose spring housings are vented to the discharge side of the valve and to the atmosphere.

By considering the forces acting on the disc (with area AD), it can be seen that the required opening force (equivalent to the product of inlet pressure (PV) and the nozzle area (AN)) is the sum of the spring force (FS) and the force due to the backpressure (PB) acting on the top and bottom of the disc. In the case of a spring housing vented to the discharge side of the valve (an ASME conventional safety relief valve, see Figure 9.2.1 (a)), the required opening force is:

In both cases, if a significant superimposed backpressure exists, its effects on the set pressure need to be considered when designing a safety valve system.

Once the valve starts to open, the effects of built-up backpressure also have to be taken into account. For a conventional safety valve with the spring housing vented to the discharge side of the valve, see Figure 9.2.1 (a), the effect of built-up backpressure can be determined by considering Equation 9.2.1 and by noting that once the valve starts to open, the inlet pressure is the sum of the set pressure, PS, and the overpressure, PO.

In both cases, if a significant superimposed backpressure exists, its effects on the set pressure need to be considered when designing a safety valve system.

Once the valve starts to open, the effects of built-up backpressure also have to be taken into account. For a conventional safety valve with the spring housing vented to the discharge side of the valve, see Figure 9.2.1 (a), the effect of built-up backpressure can be determined by considering Equation 9.2.1 and by noting that once the valve starts to open, the inlet pressure is the sum of the set pressure, PS, and the overpressure, PO.

Balanced safety valves are those that incorporate a means of eliminating the effects of backpressure. There are two basic designs that can be used to achieve this:

Although there are several variations of the piston valve, they generally consist of a piston type disc whose movement is constrained by a vented guide. The area of the top face of the piston, AP, and the nozzle seat area, AN, are designed to be equal. This means that the effective area of both the top and bottom surfaces of the disc exposed to the backpressure are equal, and therefore any additional forces are balanced. In addition, the spring bonnet is vented such that the top face of the piston is subjected to atmospheric pressure, as shown in Figure 9.2.2.

The bellows arrangement prevents backpressure acting on the upper side of the disc within the area of the bellows. The disc area extending beyond the bellows and the opposing disc area are equal, and so the forces acting on the disc are balanced, and the backpressure has little effect on the valve opening pressure.

Bellows failure is an important concern when using a bellows balanced safety valve, as this may affect the set pressure and capacity of the valve. It is important, therefore, that there is some mechanism for detecting any uncharacteristic fluid flow through the bellows vents. In addition, some bellows balanced safety valves include an auxiliary piston that is used to overcome the effects of backpressure in the case of bellows failure. This type of safety valve is usually only used on critical applications in the oil and petrochemical industries.

In addition to reducing the effects of backpressure, the bellows also serve to isolate the spindle guide and the spring from the process fluid, this is important when the fluid is corrosive.

Since balanced pressure relief valves are typically more expensive than their unbalanced counterparts, they are commonly only used where high pressure manifolds are unavoidable, or in critical applications where a very precise set pressure or blowdown is required.

This type of safety valve uses the flowing medium itself, through a pilot valve, to apply the closing force on the safety valve disc. The pilot valve is itself a small safety valve.

The diaphragm type is typically only available for low pressure applications and it produces a proportional type action, characteristic of relief valves used in liquid systems. They are therefore of little use in steam systems, consequently, they will not be considered in this text.

The piston type valve consists of a main valve, which uses a piston shaped closing device (or obturator), and an external pilot valve. Figure 9.2.4 shows a diagram of a typical piston type, pilot operated safety valve.

The piston and seating arrangement incorporated in the main valve is designed so that the bottom area of the piston, exposed to the inlet fluid, is less than the area of the top of the piston. As both ends of the piston are exposed to the fluid at the same pressure, this means that under normal system operating conditions, the closing force, resulting from the larger top area, is greater than the inlet force. The resultant downward force therefore holds the piston firmly on its seat.

If the inlet pressure were to rise, the net closing force on the piston also increases, ensuring that a tight shut-off is continually maintained. However, when the inlet pressure reaches the set pressure, the pilot valve will pop open to release the fluid pressure above the piston. With much less fluid pressure acting on the upper surface of the piston, the inlet pressure generates a net upwards force and the piston will leave its seat. This causes the main valve to pop open, allowing the process fluid to be discharged.

When the inlet pressure has been sufficiently reduced, the pilot valve will reclose, preventing the further release of fluid from the top of the piston, thereby re-establishing the net downward force, and causing the piston to reseat.

Pilot operated safety valves offer good overpressure and blowdown performance (a blowdown of 2% is attainable). For this reason, they are used where a narrow margin is required between the set pressure and the system operating pressure. Pilot operated valves are also available in much larger sizes, making them the preferred type of safety valve for larger capacities.

One of the main concerns with pilot operated safety valves is that the small bore, pilot connecting pipes are susceptible to blockage by foreign matter, or due to the collection of condensate in these pipes. This can lead to the failure of the valve, either in the open or closed position, depending on where the blockage occurs.

The terms full lift, high lift and low lift refer to the amount of travel the disc undergoes as it moves from its closed position to the position required to produce the certified discharge capacity, and how this affects the discharge capacity of the valve.

A full lift safety valve is one in which the disc lifts sufficiently, so that the curtain area no longer influences the discharge area. The discharge area, and therefore the capacity of the valve are subsequently determined by the bore area. This occurs when the disc lifts a distance of at least a quarter of the bore diameter. A full lift conventional safety valve is often the best choice for general steam applications.

The disc of a high lift safety valve lifts a distance of at least 1/12th of the bore diameter. This means that the curtain area, and ultimately the position of the disc, determines the discharge area. The discharge capacities of high lift valves tend to be significantly lower than those of full lift valves, and for a given discharge capacity, it is usually possible to select a full lift valve that has a nominal size several times smaller than a corresponding high lift valve, which usually incurs cost advantages.Furthermore, high lift valves tend to be used on compressible fluids where their action is more proportional.

In low lift valves, the disc only lifts a distance of 1/24th of the bore diameter. The discharge area is determined entirely by the position of the disc, and since the disc only lifts a small amount, the capacities tend to be much lower than those of full or high lift valves.

Except when safety valves are discharging, the only parts that are wetted by the process fluid are the inlet tract (nozzle) and the disc. Since safety valves operate infrequently under normal conditions, all other components can be manufactured from standard materials for most applications. There are however several exceptions, in which case, special materials have to be used, these include:

Cast steel -Commonly used on higher pressure valves (up to 40 bar g). Process type valves are usually made from a cast steel body with an austenitic full nozzle type construction.

For all safety valves, it is important that moving parts, particularly the spindle and guides are made from materials that will not easily degrade or corrode. As seats and discs are constantly in contact with the process fluid, they must be able to resist the effects of erosion and corrosion.

For process applications, austenitic stainless steel is commonly used for seats and discs; sometimes they are ‘stellite faced’ for increased durability. For extremely corrosive fluids, nozzles, discs and seats are made from special alloys such as ‘monel’ or ‘hastelloy’.

The spring is a critical element of the safety valve and must provide reliable performance within the required parameters. Standard safety valves will typically use carbon steel for moderate temperatures. Tungsten steel is used for higher temperature, non-corrosive applications, and stainless steel is used for corrosive or clean steam duty. For sour gas and high temperature applications, often special materials such as monel, hastelloy and ‘inconel’ are used.

A key option is the type of seating material used. Metal-to-metal seats, commonly made from stainless steel, are normally used for high temperature applications such as steam. Alternatively, resilient discs can be fixed to either or both of the seating surfaces where tighter shut-off is required, typically for gas or liquid applications. These inserts can be made from a number of different materials, but Viton, nitrile or EPDM are the most common. Soft seal inserts are not generally recommended for steam use.

Standard safety valves are generally fitted with an easing lever, which enables the valve to be lifted manually in order to ensure that it is operational at pressures in excess of 75% of set pressure. This is usually done as part of routine safety checks, or during maintenance to prevent seizing. The fitting of a lever is usually a requirement of national standards and insurance companies for steam and hot water applications. For example, the ASME Boiler and Pressure Vessel Code states that pressure relief valves must be fitted with a lever if they are to be used on air, water over 60°C, and steam.

A standard or open lever is the simplest type of lever available. It is typically used on applications where a small amount of leakage of the fluid to the atmosphere is acceptable, such as on steam and air systems, (see Figure 9.2.5 (a)).

Where it is not acceptable for the media to escape, a packed lever must be used. This uses a packed gland seal to ensure that the fluid is contained within the cap, (see Figure 9.2.5 (b)).

For service where a lever is not required, a cap can be used to simply protect the adjustment screw. If used in conjunction with a gasket, it can be used to prevent emissions to the atmosphere, (see Figure 9.2.6).

A test gag (Figure 9.2.7) may be used to prevent the valve from opening at the set pressure during hydraulic testing when commissioning a system. Once tested, the gag screw is removed and replaced with a short blanking plug before the valve is placed in service.

The amount of fluid depends on the particular design of safety valve. If emission of this fluid into the atmosphere is acceptable, the spring housing may be vented to the atmosphere – an open bonnet. This is usually advantageous when the safety valve is used on high temperature fluids or for boiler applications as, otherwise, high temperatures can relax the spring, altering the set pressure of the valve. However, using an open bonnet exposes the valve spring and internals to environmental conditions, which can lead to damage and corrosion of the spring.

When the fluid must be completely contained by the safety valve (and the discharge system), it is necessary to use a closed bonnet, which is not vented to the atmosphere. This type of spring enclosure is almost universally used for small screwed valves and, it is becoming increasingly common on many valve ranges since, particularly on steam, discharge of the fluid could be hazardous to personnel.

Some safety valves, most commonly those used for water applications, incorporate a flexible diaphragm or bellows to isolate the safety valve spring and upper chamber from the process fluid, (see Figure 9.2.9).

An elastomer bellows or diaphragm is commonly used in hot water or heating applications, whereas a stainless steel one would be used on process applications employing hazardous fluids.

As soon as mankind was able to boil water to create steam, the necessity of the safety device became evident. As long as 2000 years ago, the Chinese were using cauldrons with hinged lids to allow (relatively) safer production of steam. At the beginning of the 14th century, chemists used conical plugs and later, compressed springs to act as safety devices on pressurised vessels.

Early in the 19th century, boiler explosions on ships and locomotives frequently resulted from faulty safety devices, which led to the development of the first safety relief valves.

In 1848, Charles Retchie invented the accumulation chamber, which increases the compression surface within the safety valve allowing it to open rapidly within a narrow overpressure margin.

Today, most steam users are compelled by local health and safety regulations to ensure that their plant and processes incorporate safety devices and precautions, which ensure that dangerous conditions are prevented.

The principle type of device used to prevent overpressure in plant is the safety or safety relief valve. The safety valve operates by releasing a volume of fluid from within the plant when a predetermined maximum pressure is reached, thereby reducing the excess pressure in a safe manner. As the safety valve may be the only remaining device to prevent catastrophic failure under overpressure conditions, it is important that any such device is capable of operating at all times and under all possible conditions.

Safety valves should be installed wherever the maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP) of a system or pressure-containing vessel is likely to be exceeded. In steam systems, safety valves are typically used for boiler overpressure protection and other applications such as downstream of pressure reducing controls. Although their primary role is for safety, safety valves are also used in process operations to prevent product damage due to excess pressure. Pressure excess can be generated in a number of different situations, including:

The terms ‘safety valve’ and ‘safety relief valve’ are generic terms to describe many varieties of pressure relief devices that are designed to prevent excessive internal fluid pressure build-up. A wide range of different valves is available for many different applications and performance criteria.

In most national standards, specific definitions are given for the terms associated with safety and safety relief valves. There are several notable differences between the terminology used in the USA and Europe. One of the most important differences is that a valve referred to as a ‘safety valve’ in Europe is referred to as a ‘safety relief valve’ or ‘pressure relief valve’ in the USA. In addition, the term ‘safety valve’ in the USA generally refers specifically to the full-lift type of safety valve used in Europe.

Pressure relief valve- A spring-loaded pressure relief valve which is designed to open to relieve excess pressure and to reclose and prevent the further flow of fluid after normal conditions have been restored. It is characterised by a rapid-opening ‘pop’ action or by opening in a manner generally proportional to the increase in pressure over the opening pressure. It may be used for either compressible or incompressible fluids, depending on design, adjustment, or application.

Safety valves are primarily used with compressible gases and in particular for steam and air services. However, they can also be used for process type applications where they may be needed to protect the plant or to prevent spoilage of the product being processed.

Relief valve - A pressure relief device actuated by inlet static pressure having a gradual lift generally proportional to the increase in pressure over opening pressure.

Relief valves are commonly used in liquid systems, especially for lower capacities and thermal expansion duty. They can also be used on pumped systems as pressure overspill devices.

Safety relief valve - A pressure relief valve characterised by rapid opening or pop action, or by opening in proportion to the increase in pressure over the opening pressure, depending on the application, and which may be used either for liquid or compressible fluid.

In general, the safety relief valve will perform as a safety valve when used in a compressible gas system, but it will open in proportion to the overpressure when used in liquid systems, as would a relief valve.

Safety valve- A valve which automatically, without the assistance of any energy other than that of the fluid concerned, discharges a quantity of the fluid so as to prevent a predetermined safe pressure being exceeded, and which is designed to re-close and prevent further flow of fluid after normal pressure conditions of service have been restored.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

When selecting spring loaded safety valves, an accurate knowledge and consideration of the specific operating conditions are vital to ensure that these devices work reliably. As optimal resource use becomes an increasingly relevant criterion, plant owners focus particular attention on components that can be depended on absolutely – even at their physical limits.

In the design of a safety valve, the existence of a backpressure must be considered in addition to the usual parameters for dimensioning. In this present report, the function of a safety valve is intended to be shown when a constant superimposed backpressure is present in the discharge and thus acts against the direction of opening of the safety valve.

A spring loaded safety valve is a valve which allows a defined amount of fluid to be discharged automatically – unaided by any form of energy other than the medium itself – in order to prevent a predetermined safe pressure from being exceeded. It is designed in such a way that it closes as soon as normal conditions are restored, so that no more fluid exits [2, p. 4]. As the final protective device in the technical system, it plays a special role and must be depended on to work absolutely reliably. Careful design and sizing by the systems engineer as well as expert execution of the entire installation are essential for proper functioning. As far as the safety valve itself is concerned, it is important that the spring(s) and disc (closure component) can perform their work (lift) undisturbed. If this is not the case, in other words if the required lift is restricted, impeded or blocked, delayed actuation, flutter and reduced performance could be the outcome – in short, operation outside the limits allowed by the regulations. The safety and reliability of the installation as a whole would be jeopardised. All safety valves approved under European or American regulations are subject to strict standards and component monitoring procedures. The safety valves manufactured by ARI-Armaturen are approved, for example, to DIN EN ISO 4126 [5] and ASME VIII Div. 1 [7].

In other words, the valve opens if the pressure and hence the force underneath the disc in the pressure vessel is greater than the force which presses the disc against the seat (nozzle). A basic distinction is made here between two different types of actuation, namely sudden (rapid opening) and almost continuous (but not necessarily linear opening) [2, p. 4].

Whereas the operational behaviour of spring loaded safety valves with a built-up backpres-sure has already been the object of a detailed study in [1], this paper examines their operational behaviour with a preset, constant superimposed backpressure and a cold differential test pressure (CDTP) setting (Figure 1). Plant planners and owners are particularly interested in answers to the following two questions:

What effect does a constant superimposed backpressure have on the safety valve’s functionality (opening pressure difference, closing pressure difference), performance and leakproofness and to what extent does a cold differential test pressure setting influence the valve’s functional characteristic?

In the context of safety valves, we differentiate between built-up backpressure and superimposed backpressure. Amongst other things, the existence of backpressure is conditional on the use of a metal bellow. The built-up backpressure is the excess pressure in the outlet pipe of the safety valve which is built up during the blow-off phase (opening) and is therefore variable. The superimposed backpressure is the excess pressure which is already present in the outlet pipe of the safety valve before the blow-off phase begins. It can be either constant or variable (Figure 2).

This additional force must be taken into account when setting the compression spring, which requires correspondingly less preload [6, p. 17]. The safety valve will otherwise be actuated at too high a pressure, namely at the sum of equation (3).

The procedure described in section background is the norm when sizing and setting American safety valves to API/ASME [6, p. 25]; it is referred to as the „CDTP setting“:

According to the European regulatory framework provided by DIN EN ISO 4126 [2, p. 5], the CDTP may include a correction for backpres-sure and temperature. Extensive measurements to determine this have been carried out on an air dynamometer at ARI-Armaturen (refer to section results).

The backpressure can be compensated by installing a metal bellows (Figure 3). The optimal effect is achieved if the mean bellows diameter corresponds as closely as possible to the mean seat diameter of the safety valve. A bellows is always required if the superimposed backpressure FBPsuperimposed is variable because a variable backpressure will otherwise cause the set pressure to change constantly.

The operational behaviour must be assessed using the parameters described in the recognised standards [2, 3]. The backpressure ratio, which determines whether critical or subcritical operating conditions apply, is crucial here. Critical operation means that if the pressure behind the valve seat drops further, the mass flow no longer increases [3, p. 7]. Under subcritical flow conditions, therefore, the term must be multiplied by the correction factor Kb in order to calculate the theoretical mass flow. According to [3, p. 8 and 23], Kb can be either calculated or read off, it has a direct influence on the determination of the coefficient of discharge Kd (or Kdr) [3, p. 7ff].

The safety valve has been adjusted to the stated pressure (Definition: Initial Audible). Then the constant backpressure was increased and accounted for as a percentage of each explains the measured values. To reduce the time for rebuild on an adjustment of the valve (clamping bolt) and thus the CDTP correction has been omitted. Additionally, it was kept almost nearly constant through the use of an automatic control valve in the discharge line of the backpressure to the set value. The influence of built-up backpressure was negligible. The results are accordingly plotted in section results (extract 5 bar), based on equation (3) and the set pressure should correspond to the sum of Fspringforce + FBPsuperimposed. Three measurements were performed for each setting; the mean value in each case was taken as a basis for the results shown in figure 5 to 8.

The safety valve responds within the allowed limits, thus despite the presence of constant superimposed backpressure and a setting according to (3) correctly, the general function characteristic of the response is not adversely affected. Despite the constant superimposed backpressure, the valve reaches its full stroke. In the version without metal bellows, the opening pressure difference increases linearly to the backpressure ratio (Figure 6), but is within the specified range, with metal bellows it is almost constant despite increasing backpressure ratio (Figure 8). A constant backpressure and the resulting adjustment according to (4) affects the working behaviour of the safety valve in particular to the effect that the blowdown changed (it decreases linearly to the backpressure ratio (Figure 8)). This means there is a risk that the safety valve with increasing backpressure ratio or a higher opening pressure after the response no longer closes reliably and has a permanent, „creeping“ leakage. In the design and sizing of safety valves with constant backpressure of the concrete application and the operating conditions are therefore always taken into account. For this purpose, the respective manufacturer should be contacted in particular to take into account the operating limits and changing operating parameters in the selection and interpretation.

The effects of exceeding safe pressure levels in an unprotected pressure vessel or system, can have catastrophic effects on both plant and personnel. Safety relief valves should be used to protect any pressurised system from the effects of exceeding its design pressure limit.

A safety relief valve is designed to automatically discharge gas, vapour or liquid from any pressure containing system, preventing a predetermined safe pressure being exceeded, and protecting plant and personnel.

A valve which automatically discharges gases and vapours so as to prevent a predetermined safe pressure being exceeded. It is characterised by a rapid full opening action and is used for steam, gases or vapour service.

A valve which automatically discharges fluid, usually liquid, when a predetermined upstream pressure is exceeded. The term is commonly used for pressure relieving valves in which the lift is proportional to the increase in pressure above the set pressure.

A valve which will automatically discharge gases, vapours or liquids, to prevent a predetermined safe pressure being exceeded. It is characterised by a rapid opening action.

The Bailey 707 Safety Relief Valve encompasses a top guided design, combining an unobstructed seat bore with high lift capability. This bronze bodied valve can be supplied with a resilient or metal trim with a choice of screwed and flanged connections.

The Bailey 707 is certified to BS EN 4126 Part 1 (BS6759 pt 1:2:3) and is suitable for duty on air/gas, steam/hot water (above 100ºC) and process liquid.

Test levers are available for inline safety checking, alternatively a sealed dome can be supplied for service conditions requiring a pressure tight seal on the discharge side, eg. liquid service with enclosed discharge.

Positive reseating is achieved with freely pivoting EPDM discs for gas, hot water and other liquid duties up to 150°C. Optional Aflas soft seats increase the range to 200°C. Precision lapped stainless steel trim gives positive re-seating for steam duty at higher temperatures. Fitted with a test lever for inline safety checking, or alternatively with a sealed dome for service conditions requiring a pressure tight seal on the discharge side, eg. liquid service.

The 716T is the ultimate solution to hot water system protection, it protects unvented hot water systems, against both excess pressure and excess temperature. Increasing pressure is sensed by the spring, which automatically opens the relief valve at the pre-set pressure and the integral probe independently monitors increases in temperature, safely opening the relief valve between 90°C and 95°C.

The temperature probes are designed to have a smooth surface free from crevices, to reduce mineral build-up, and are white powder coated to minimise galvanic action within the heater.

The 716T has a bronze body, Dzr brass internals and silicone seat in accordance with potable water code requirements. A soft seat provides leak tight operation. The spring and spring chamber are protected from the hot water by the EPDM diaphragm, reducing corrosion and increasing life in service.

The 746 Safety Relief Valve incorporates a freely pivoting disc, which ensures correct alignment with the nozzle. The combination of top guiding,unobstructed seat bore and full lift capability ensures the highest possible discharge rate thus maximum plant protection.

The 746 safety relief valve is available in both conventional and balanced bellows types, and features a special disc style for liquid application, which enhances valve performance.

The ‘conventional’ arrangement is suitable for applications where the built up pressure will not exceed 5%. The conventional valve can also be used in systems where the superimposed backpressure is at a constant level (up to 80%).

The ‘balanced bellows’ arrangement is for applications where several safety relief valves discharge into a common discharge manifold, or in any circumstances where a variable back pressure can occur, up to a maximum of 40%.

The 756 Safety Valve combines a top piston guided valve and an unobstructed seat bore with a full lift capability, giving maximum discharge capacity. The design incorporates an adjustable blowdown ring and meets all the requirements of BS6759 Part 1.

A freely pivoting disc and precision lapped stainless steel trim gives positive re-seating for steam duty. As standard the 756 is fitted with a test lever for inline testing. Ideally suited to applications on steam boilers and pipelines where blowdown tolerances are critical.

The 766 Safety Valve is a double spring high lift valve with high discharge capacity. The top guided piston design incorporates an adjustable blowdown ring and meets all the requirements of BS6759 Part 1.

A freely pivoting disc and precision lapped stainless steel trim gives positive re-seating for steam duty. Fitted as standard with test lever for inline testing.Ideally suited to applications on steam boilers and pipelines where blowdown tolerances are critical.

The 776 Safety Relief Valve is designed for cryogenic duty down to -196°C. The valve combines a full lift design and top guided construction with an unobstructed seat bore to provide maximum discharge capacity. Positive sealing is achieved through a freely pivoted disc with Kel F (PCTFE) soft seat technology.

This spring operated liquid relief valve has a cartridge type assembly which can be withdrawn from the body without disturbing the spring setting and hence relieving pressure. This allows the seating surfaces to be cleaned without the need to reset the valve. The 480 is a bronze relief valve, the 485 is also bronze with a renewable stainless steel seat and disc, while the 490 is all stainless steel.

Typically for use on positive displacement pumps, for relief or bypass duties. The spring cartridge assembly can be supplied separately for use as an integral pump bypass relief valve.

The type 616D is a spring operated high capacity safety valve for low-pressure air applications. It is designed to deliver precise relieving and re-seating pressures while the protected open discharge gives downward flow. The non-stick seating surfaces give positive shut-off and freedom from sticking, whilst the mixture of aluminium and gunmetal make it light but

A relief system is an emergency system for discharging gas during abnormal conditions, by manual or controlled means or by an automatic pressure relief valve from a pressurized vessel or piping system, to the atmosphere to relieve pressures in excess of the maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP).

A scrubbing vessel should be provided for liquid separation if liquid hydrocarbons are anticipated. The relief-system outlet may be either vented or flared. If designed properly, vent or flare emergency-relief systems from pressure vessels may be combined.

Some facilities include systems for depressuring pressure vessels in the event of an emergency shutdown. The depressuring-system control valves may be arranged to discharge into the vent, flare, or relief systems. The possibility of freezing and hydrate formation during high-pressure releases to the atmosphere should be considered.

Defining reasonable total relief loads for the combined relief header or disposal system and designing an appropriate disposal system with minimum adverse impact to personnel safety, plant-process system integrity, and the environment.

These considerations are interrelated in such a way that makes it impossible to establish a procedural guideline that would be valid for most cases. The design of one portion of a relief system must be considered in light of its effects on the relief system.

There are a number of industry codes, standards, and recommended practices that provide guidance in the sizing, selection, and installation of relief devices and systems. The American Soc. of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) Pressure Vessel Code, Sec. VIII, Division 1, paragraph UG-127, lists the relief-valve code requirements.RP 520, Part 1, provides an overview of the types of relief devices, causes of overpressure, relief-load determination, and procedures for selecting and sizing relief devices.RP 520, Part 2, provides guidance on the installation of relief devices,RP 521 provides guidance on the selection and design of disposal systems.

The most common causes of overpressure in upstream operations are blocked discharge, gas blowby, and fire. When the worst-case relief load is caused by a control valve failing to open (blocked discharge), the relief device should be sized with full-sized trim in the control valve, even if the actual valve has reduced trim. When the worst-case relief load is caused by gas blowby, the relief device should be sized with full-sized trim in the smallest valve in the liquid-outlet line, even if the actual valve has reduced trim. Many vessels are insulated for energy savings. Thermal insulation limits the heat absorption from fire exposure as long as it is intact. It is essential that effective weather protection be provided so that insulation will not be removed by high-velocity fire-hose streams.

Conventional spring loaded. In the conventional spring-loaded valve (Fig. 1), the bonnet, spring, and guide are exposed to the released fluids. If the bonnet is vented to the atmosphere, relief-system backpressure decreases the set pressure. If the bonnet is vented internally to the outlet, relief-system backpressure increases the set pressure. The conventional spring-loaded valve is used in noncorrosive services and where backpressure is less than 10% of the set point.

Balanced spring-loaded. The balanced spring-loaded valve incorporates a means to protect the bonnet, spring, and guide from the released fluids and minimizes the effects of backpressure. The disk area vented to the atmosphere is exactly equal to the disk area exposed to backpressure. These valves can be used in corrosive or dirty service and with variable backpressure.

Pilot operated. The pilot-operated valve is com

8613371530291

8613371530291