boiler safety valve setting formula price

In order to ensure that the maximum allowable accumulation pressure of any system or apparatus protected by a safety valve is never exceeded, careful consideration of the safety valve’s position in the system has to be made. As there is such a wide range of applications, there is no absolute rule as to where the valve should be positioned and therefore, every application needs to be treated separately.

A common steam application for a safety valve is to protect process equipment supplied from a pressure reducing station. Two possible arrangements are shown in Figure 9.3.3.

The safety valve can be fitted within the pressure reducing station itself, that is, before the downstream stop valve, as in Figure 9.3.3 (a), or further downstream, nearer the apparatus as in Figure 9.3.3 (b). Fitting the safety valve before the downstream stop valve has the following advantages:

• The safety valve can be tested in-line by shutting down the downstream stop valve without the chance of downstream apparatus being over pressurised, should the safety valve fail under test.

• When setting the PRV under no-load conditions, the operation of the safety valve can be observed, as this condition is most likely to cause ‘simmer’. If this should occur, the PRV pressure can be adjusted to below the safety valve reseat pressure.

Indeed, a separate safety valve may have to be fitted on the inlet to each downstream piece of apparatus, when the PRV supplies several such pieces of apparatus.

• If supplying one piece of apparatus, which has a MAWP pressure less than the PRV supply pressure, the apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve, preferably close-coupled to its steam inlet connection.

• If a PRV is supplying more than one apparatus and the MAWP of any item is less than the PRV supply pressure, either the PRV station must be fitted with a safety valve set at the lowest possible MAWP of the connected apparatus, or each item of affected apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve.

• The safety valve must be located so that the pressure cannot accumulate in the apparatus viaanother route, for example, from a separate steam line or a bypass line.

It could be argued that every installation deserves special consideration when it comes to safety, but the following applications and situations are a little unusual and worth considering:

• Fire - Any pressure vessel should be protected from overpressure in the event of fire. Although a safety valve mounted for operational protection may also offer protection under fire conditions,such cases require special consideration, which is beyond the scope of this text.

• Exothermic applications - These must be fitted with a safety valve close-coupled to the apparatus steam inlet or the body direct. No alternative applies.

• Safety valves used as warning devices - Sometimes, safety valves are fitted to systems as warning devices. They are not required to relieve fault loads but to warn of pressures increasing above normal working pressures for operational reasons only. In these instances, safety valves are set at the warning pressure and only need to be of minimum size. If there is any danger of systems fitted with such a safety valve exceeding their maximum allowable working pressure, they must be protected by additional safety valves in the usual way.

In order to illustrate the importance of the positioning of a safety valve, consider an automatic pump trap (see Block 14) used to remove condensate from a heating vessel. The automatic pump trap (APT), incorporates a mechanical type pump, which uses the motive force of steam to pump the condensate through the return system. The position of the safety valve will depend on the MAWP of the APT and its required motive inlet pressure.

This arrangement is suitable if the pump-trap motive pressure is less than 1.6 bar g (safety valve set pressure of 2 bar g less 0.3 bar blowdown and a 0.1 bar shut-off margin). Since the MAWP of both the APT and the vessel are greater than the safety valve set pressure, a single safety valve would provide suitable protection for the system.

Here, two separate PRV stations are used each with its own safety valve. If the APT internals failed and steam at 4 bar g passed through the APT and into the vessel, safety valve ‘A’ would relieve this pressure and protect the vessel. Safety valve ‘B’ would not lift as the pressure in the APT is still acceptable and below its set pressure.

It should be noted that safety valve ‘A’ is positioned on the downstream side of the temperature control valve; this is done for both safety and operational reasons:

Operation - There is less chance of safety valve ‘A’ simmering during operation in this position,as the pressure is typically lower after the control valve than before it.

Also, note that if the MAWP of the pump-trap were greater than the pressure upstream of PRV ‘A’, it would be permissible to omit safety valve ‘B’ from the system, but safety valve ‘A’ must be sized to take into account the total fault flow through PRV ‘B’ as well as through PRV ‘A’.

A pharmaceutical factory has twelve jacketed pans on the same production floor, all rated with the same MAWP. Where would the safety valve be positioned?

One solution would be to install a safety valve on the inlet to each pan (Figure 9.3.6). In this instance, each safety valve would have to be sized to pass the entire load, in case the PRV failed open whilst the other eleven pans were shut down.

If additional apparatus with a lower MAWP than the pans (for example, a shell and tube heat exchanger) were to be included in the system, it would be necessary to fit an additional safety valve. This safety valve would be set to an appropriate lower set pressure and sized to pass the fault flow through the temperature control valve (see Figure 9.3.8).

A safety valve must always be sized and able to vent any source of steam so that the pressure within the protected apparatus cannot exceed the maximum allowable accumulated pressure (MAAP). This not only means that the valve has to be positioned correctly, but that it is also correctly set. The safety valve must then also be sized correctly, enabling it to pass the required amount of steam at the required pressure under all possible fault conditions.

Once the type of safety valve has been established, along with its set pressure and its position in the system, it is necessary to calculate the required discharge capacity of the valve. Once this is known, the required orifice area and nominal size can be determined using the manufacturer’s specifications.

In order to establish the maximum capacity required, the potential flow through all the relevant branches, upstream of the valve, need to be considered.

In applications where there is more than one possible flow path, the sizing of the safety valve becomes more complicated, as there may be a number of alternative methods of determining its size. Where more than one potential flow path exists, the following alternatives should be considered:

This choice is determined by the risk of two or more devices failing simultaneously. If there is the slightest chance that this may occur, the valve must be sized to allow the combined flows of the failed devices to be discharged. However, where the risk is negligible, cost advantages may dictate that the valve should only be sized on the highest fault flow. The choice of method ultimately lies with the company responsible for insuring the plant.

For example, consider the pressure vessel and automatic pump-trap (APT) system as shown in Figure 9.4.1. The unlikely situation is that both the APT and pressure reducing valve (PRV ‘A’) could fail simultaneously. The discharge capacity of safety valve ‘A’ would either be the fault load of the largest PRV, or alternatively, the combined fault load of both the APT and PRV ‘A’.

This document recommends that where multiple flow paths exist, any relevant safety valve should, at all times, be sized on the possibility that relevant upstream pressure control valves may fail simultaneously.

The supply pressure of this system (Figure 9.4.2) is limited by an upstream safety valve with a set pressure of 11.6 bar g. The fault flow through the PRV can be determined using the steam mass flow equation (Equation 3.21.2):

Once the fault load has been determined, it is usually sufficient to size the safety valve using the manufacturer’s capacity charts. A typical example of a capacity chart is shown in Figure 9.4.3. By knowing the required set pressure and discharge capacity, it is possible to select a suitable nominal size. In this example, the set pressure is 4 bar g and the fault flow is 953 kg/h. A DN32/50 safety valve is required with a capacity of 1 284 kg/h.

Coefficients of discharge are specific to any particular safety valve range and will be approved by the manufacturer. If the valve is independently approved, it is given a ‘certified coefficient of discharge’.

This figure is often derated by further multiplying it by a safety factor 0.9, to give a derated coefficient of discharge. Derated coefficient of discharge is termed Kdr= Kd x 0.9

Critical and sub-critical flow - the flow of gas or vapour through an orifice, such as the flow area of a safety valve, increases as the downstream pressure is decreased. This holds true until the critical pressure is reached, and critical flow is achieved. At this point, any further decrease in the downstream pressure will not result in any further increase in flow.

A relationship (called the critical pressure ratio) exists between the critical pressure and the actual relieving pressure, and, for gases flowing through safety valves, is shown by Equation 9.4.2.

Overpressure - Before sizing, the design overpressure of the valve must be established. It is not permitted to calculate the capacity of the valve at a lower overpressure than that at which the coefficient of discharge was established. It is however, permitted to use a higher overpressure (see Table 9.2.1, Module 9.2, for typical overpressure values). For DIN type full lift (Vollhub) valves, the design lift must be achieved at 5% overpressure, but for sizing purposes, an overpressure value of 10% may be used.

For liquid applications, the overpressure is 10% according to AD-Merkblatt A2, DIN 3320, TRD 421 and ASME, but for non-certified ASME valves, it is quite common for a figure of 25% to be used.

Two-phase flow - When sizing safety valves for boiling liquids (e.g. hot water) consideration must be given to vaporisation (flashing) during discharge. It is assumed that the medium is in liquid state when the safety valve is closed and that, when the safety valve opens, part of the liquid vaporises due to the drop in pressure through the safety valve. The resulting flow is referred to as two-phase flow.

The required flow area has to be calculated for the liquid and vapour components of the discharged fluid. The sum of these two areas is then used to select the appropriate orifice size from the chosen valve range. (see Example 9.4.3)

Many standards do not actually specify sizing formula for two-phase flow and recommend that the manufacturer be contacted directly for advice in these instances.

Chatter is devastating to the internals of a Boiler Safety Valve. However, there is an even more important reason to avoid chatter at all cost. Chatter prevents the Safety Valve from reaching or sustaining full lift. This results in the Boiler is not being protected from a catastrophic overpressure event. Chatter may be the result of several issues. The least likely is an inaccurately adjusted Safety Valve. More than likely, chatter is an issue of piping or installation. Inlet or outlet piping may be the culprit. Reduced Piping, too much length or too many bends (or some combination of those three) on the Inlet or the Outlet may result in Chatter. On some occasions, the Safety Valve is improperly sized resulting in chatter due to insufficient flow through the Safety Valve when it is called on to operate. In other words, the Safety Valve is oversized and there is enough pressure to cause the Safety Valve to lift, but not enough flow to keep it open. Bigger is not always better. All the issues referred to above result in pressure drop at the PRV Inlet, which causes chatter.

The only mentions of pressure drop in ASME Sec I, Power Boiler Code, are in PG-68.1 for Superheater Safety Valve Set Pressure calculation and in PG-68.4 for Reheater Outlet Safety Valve Set Pressure calculation. PG-72.1 is a requirement designed to ensure the Safety Valve does not chatter. Notice PG-72 has a title that refers to “Operation of Pressure Relief Valves.” It is referring to the Blowdown Ring Settings, not the inlet Pressure Drop due to piping losses.

In a related code, ASME Sec VIII-1, UG-135, INSTALLATION, in UG-135(b)(1) states, “The opening through all pipe, fittings, and nonreclosing pressure relief devices (if installed) between a pressure vessel and its pressure relief valve shall have at least the area of the pressure relief valve inlet . The characteristics of this upstream system shall be such that the pressure drop will not reduce the relieving capacity below that required or adversely affect the proper operation of the pressure relief valve.”

ASME Sec VIII-1, Non-Mandatory Appendix M, M-6 (a) states, “M-6 INLET PRESSURE DROP FOR HIGH LIFT, TOP-GUIDED SAFETY, SAFETY RELIEF, AND PILOT-OPERATED PRESSURE RELIEF VALVES IN COMPRESSIBLE FLUID SERVICE (a) The nominal pipe size of all piping, valves and fittings, and vessel components between a pressure vessel and its safety, safety relief, or pilot-operated pressure relief valves shall be at least as large as the nominal size of the device inlet, and the flow characteristics of the upstream system shall be such that the cumulative total of all nonrecoverable inlet losses shall not exceed 3% of the valve set pressure. The inlet pressure losses will be based on the valve nameplate capacity corrected for the characteristics of the flowing fluid.

Following the requirements for Safety Valve installation in ASME Code, Sec I, Power Boilers, will resolve the chatter issue without calculating pressure losses in piping. Refer to ASME Sec I, PG-71, “Mounting of Pressure Relief Valves.” The restrictions on size and length of piping should be sufficient to prevent chatter due to piping losses.

Regarding the least likely cause of chatter, i.e. Safety Valve adjustment, if the Upper Adjusting Ring (Guide Ring) is too high, the Safety Valve will pop, but will not remain open. It will reclose and immediately pop again resulting in chatter. This is due to the Upper Ring providing an "outer wall" to the Huddling Chamber to keep the Steam underneath the Disc long enough to achieve full lift. Setting the Upper Ring too high removes the "outer wall" of the Huddling Chamber resulting in chatter. Setting the Safety Valve in accordance with PG-73.5.2 (a), which states, “Pressure relief valves for steam service shall be tested with steam. The blowdown control elements of the pressure relief valve shall be set to the manufacturer"s specifications,” should eliminate the possibility of chatter due to an adjusting ring setting. It should be noted that the typical, ASME Sec VIII, Pressure Relief Valve, is a single ring design, Safety-Relief Valve. The Adjusting Ring Setting of the Single Ring Design, Safety-Relief Valve will not result in Chatter.

Pressure relief valves are used to protect equipment from excessive overpressure. Properly sized relief valves will provide the required protection, while also avoiding issues with excessive flow rates, including: possible valve damage, impaired performance, undersized discharge piping and effluent handling systems, and higher costs.

Many scenarios can result in an increased vessel pressure, and each scenario may result in a different valve size. It is generally recommended to perform multiple case studies to find the most conservative sizing. Some typical cases include:

In any of these scenarios, the pressure will increase until a predetermined relief pressure is reached, at which point the relief pressure valve will open, decreasing the pressure after the turnaround time. The first step in sizing a Relief Valve in ProMax is to determine which scenario you are interested in modeling.

The Relief Valve Sizing in ProMax is performed as a stream analysis. Any stream in ProMax may have one or more Relief Valve Sizing Analyses added, so multiple cases can be studied in a single stream if desired.

There are many different standards for Relief Valve Sizing, each applying different assumptions, thus giving different results. For instance, API 520, one of the most cited standards, assumes both a mechanical and thermodynamic equilibrium, and constant phase properties during relief. Alternatively, the EN ISA 4126 standard accounts for thermodynamic non-equilibrium. ProMax currently supports six different sets of Relief Valve Sizing Standards:

Next, an appropriate relief type must be selected, as sizing depends on the type of relief device selected. The operation of conventional spring-loaded pressure relief valve is based on a force balance: the spring-load is preset to apply a force opposite in amount to the pressure force exerted by the fluid on the other side when it is at the set pressure. When the fluid pressure exceeds the set pressure, the pressure force overcomes the spring force, and the valve opens. Any back pressure (downstream pressure) is additive to the spring force; if this back pressure varies, then the pressure at which the valve opens will vary. Bellows are used to maintain a constant relief pressure despite back pressure variations. Rupture disc relief valves do not reclose after activation; preference should usually be given to reclosing relief devices for both safety and reliability. The most common valve types include:

Balanced Bellows- spring loaded pressure relief valve that incorporates a bellows for minimizing the effect of back pressure on the operational characteristics of the valve.

Pilot Operated- a pressure relief valve in which the major relieving device or main valve is combined with and controlled by a self-actuated auxiliary pressure relief valve (pilot).

The Relief Temperature is determined by which pressure relief scenario you have chosen to model, and should be the temperature of the fluid at the time that the valve is expected to open. ProMax assumes that the Relief Temperature will be the current stream temperature, however, if your particular scenario requires that this be adjusted, it can be overwritten directly in the analysis dialog.

The Over Pressure is usually expressed as a percentage of the Set Pressure. For spring-operated relief valves, a small amount of leakage occurs at 92-95% of theSet Pressure, and sufficient Over Pressure is necessary to achieve full lift. ASME-certified relief valves are required to reach full-rated capacity at 10% or less overpressure.

Once you’ve determined your emergency scenario, and specified the relieving conditions and flowrate, and the appropriate standard, ProMax will calculate the Effective Discharge Area. This value is used to select the appropriately sized Pressure Relief Valve.

Although an orifice is often used to describe the minimum flow area constricted in the valve, the geometry and relief area calculations are more appropriately modeled based on an ideal (isentropic) nozzle. The expression for the mass flux (Gn) in an ideal nozzle is obtained directly from Bernoulli’s equation in the nozzle:

This type of flow is often encountered at metering devices in chemical processing and in relief valve sizing applications where both non-condensable and condensable (flashing) components

This term is an estimation used in sizing pressure relief valves for two-phase liquid/vapor applications when the system has less than 0.1 wt% H2, a nominal boiling range less than 150°F, and

As such, there are multiple methods of approximating the latent heat, and the Relief Valve Sizing analysis follows the methodology of the standards. For example, the API 520 standard defines “latent heat” as

A safety valve is a valve that acts as a fail-safe. An example of safety valve is a pressure relief valve (PRV), which automatically releases a substance from a boiler, pressure vessel, or other system, when the pressure or temperature exceeds preset limits. Pilot-operated relief valves are a specialized type of pressure safety valve. A leak tight, lower cost, single emergency use option would be a rupture disk.

Safety valves were first developed for use on steam boilers during the Industrial Revolution. Early boilers operating without them were prone to explosion unless carefully operated.

Vacuum safety valves (or combined pressure/vacuum safety valves) are used to prevent a tank from collapsing while it is being emptied, or when cold rinse water is used after hot CIP (clean-in-place) or SIP (sterilization-in-place) procedures. When sizing a vacuum safety valve, the calculation method is not defined in any norm, particularly in the hot CIP / cold water scenario, but some manufacturers

The earliest and simplest safety valve was used on a 1679 steam digester and utilized a weight to retain the steam pressure (this design is still commonly used on pressure cookers); however, these were easily tampered with or accidentally released. On the Stockton and Darlington Railway, the safety valve tended to go off when the engine hit a bump in the track. A valve less sensitive to sudden accelerations used a spring to contain the steam pressure, but these (based on a Salter spring balance) could still be screwed down to increase the pressure beyond design limits. This dangerous practice was sometimes used to marginally increase the performance of a steam engine. In 1856, John Ramsbottom invented a tamper-proof spring safety valve that became universal on railways. The Ramsbottom valve consisted of two plug-type valves connected to each other by a spring-laden pivoting arm, with one valve element on either side of the pivot. Any adjustment made to one of valves in an attempt to increase its operating pressure would cause the other valve to be lifted off its seat, regardless of how the adjustment was attempted. The pivot point on the arm was not symmetrically between the valves, so any tightening of the spring would cause one of the valves to lift. Only by removing and disassembling the entire valve assembly could its operating pressure be adjusted, making impromptu "tying down" of the valve by locomotive crews in search of more power impossible. The pivoting arm was commonly extended into a handle shape and fed back into the locomotive cab, allowing crews to "rock" both valves off their seats to confirm they were set and operating correctly.

Safety valves also evolved to protect equipment such as pressure vessels (fired or not) and heat exchangers. The term safety valve should be limited to compressible fluid applications (gas, vapour, or steam).

For liquid-packed vessels, thermal relief valves are generally characterized by the relatively small size of the valve necessary to provide protection from excess pressure caused by thermal expansion. In this case a small valve is adequate because most liquids are nearly incompressible, and so a relatively small amount of fluid discharged through the relief valve will produce a substantial reduction in pressure.

Flow protection is characterized by safety valves that are considerably larger than those mounted for thermal protection. They are generally sized for use in situations where significant quantities of gas or high volumes of liquid must be quickly discharged in order to protect the integrity of the vessel or pipeline. This protection can alternatively be achieved by installing a high integrity pressure protection system (HIPPS).

In the petroleum refining, petrochemical, chemical manufacturing, natural gas processing, power generation, food, drinks, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals industries, the term safety valve is associated with the terms pressure relief valve (PRV), pressure safety valve (PSV) and relief valve.

The generic term is Pressure relief valve (PRV) or pressure safety valve (PSV). PRVs and PSVs are not the same thing, despite what many people think; the difference is that PSVs have a manual lever to open the valve in case of emergency.

Relief valve (RV): an automatic system that is actuated by the static pressure in a liquid-filled vessel. It specifically opens proportionally with increasing pressure

Pilot-operated safety relief valve (POSRV): an automatic system that relieves on remote command from a pilot, to which the static pressure (from equipment to protect) is connected

Low pressure safety valve (LPSV): an automatic system that relieves static pressure on a gas. Used when the difference between the vessel pressure and the ambient atmospheric pressure is small.

Vacuum pressure safety valve (VPSV): an automatic system that relieves static pressure on a gas. Used when the pressure difference between the vessel pressure and the ambient pressure is small, negative and near to atmospheric pressure.

Low and vacuum pressure safety valve (LVPSV): an automatic system that relieves static pressure on a gas. Used when the pressure difference is small, negative or positive and near to atmospheric pressure.

In most countries, industries are legally required to protect pressure vessels and other equipment by using relief valves. Also, in most countries, equipment design codes such as those provided by the ASME, API and other organizations like ISO (ISO 4126) must be complied with. These codes include design standards for relief valves and schedules for periodic inspection and testing after valves have been removed by the company engineer.

Today, the food, drinks, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals industries call for hygienic safety valves, fully drainable and Cleanable-In-Place. Most are made of stainless steel; the hygienic norms are mainly 3A in the USA and EHEDG in Europe.

The first safety valve was invented by Denis Papin for his steam digester, an early pressure cooker rather than an engine.steelyard" lever a smaller weight was required, also the pressure could easily be regulated by sliding the same weight back and forth along the lever arm. Papin retained the same design for his 1707 steam pump.Greenwich in 1803, one of Trevithick"s high-pressure stationary engines exploded when the boy trained to operate the engine left it to catch eels in the river, without first releasing the safety valve from its working load.

Although the lever safety valve was convenient, it was too sensitive to the motion of a steam locomotive. Early steam locomotives therefore used a simpler arrangement of weights stacked directly upon the valve. This required a smaller valve area, so as to keep the weight manageable, which sometimes proved inadequate to vent the pressure of an unattended boiler, leading to explosions. An even greater hazard was the ease with which such a valve could be tied down, so as to increase the pressure and thus power of the engine, at further risk of explosion.

Although deadweight safety valves had a short lifetime on steam locomotives, they remained in use on stationary boilers for as long as steam power remained.

Weighted valves were sensitive to bouncing from the rough riding of early locomotives. One solution was to use a lightweight spring rather than a weight. This was the invention of Timothy Hackworth on his leaf springs.

These direct-acting spring valves could be adjusted by tightening the nuts retaining the spring. To avoid tampering, they were often shrouded in tall brass casings which also vented the steam away from the locomotive crew.

The Salter coil spring spring balance for weighing, was first made in Britain by around 1770.spring steels to make a powerful but compact spring in one piece. Once again by using the lever mechanism, such a spring balance could be applied to the considerable force of a boiler safety valve.

The spring balance valve also acted as a pressure gauge. This was useful as previous pressure gauges were unwieldy mercury manometers and the Bourdon gauge had yet to be invented.

Paired valves were often adjusted to slightly different pressures too, a small valve as a control measure and the lockable valve made larger and permanently set to a higher pressure, as a safeguard.Sinclair for the Eastern Counties Railway in 1859, had the valve spring with pressure scale behind the dome, facing the cab, and the locked valve ahead of the dome, out of reach of interference.

In 1855, John Ramsbottom, later locomotive superintendent of the LNWR, described a new form of safety valve intended to improve reliability and especially to be tamper-resistant. A pair of plug valves were used, held down by a common spring-loaded lever between them with a single central spring. This lever was characteristically extended rearwards, often reaching into the cab on early locomotives. Rather than discouraging the use of the spring lever by the fireman, Ramsbottom"s valve encouraged this. Rocking the lever freed up the valves alternately and checked that neither was sticking in its seat.

A drawback to the Ramsbottom type was its complexity. Poor maintenance or mis-assembly of the linkage between the spring and the valves could lead to a valve that no longer opened correctly under pressure. The valves could be held against their seats and fail to open or, even worse, to allow the valve to open but insufficiently to vent steam at an adequate rate and so not being an obvious and noticeable fault.Rhymney Railway, even though the boiler was almost new, at only eight months old.

Naylor valves were introduced around 1866. A bellcrank arrangement reduced the strain (percentage extension) of the spring, thus maintaining a more constant force.L&Y & NER.

All of the preceding safety valve designs opened gradually and had a tendency to leak a "feather" of steam as they approached "blowing-off", even though this was below the pressure. When they opened they also did so partially at first and didn"t vent steam quickly until the boiler was well over pressure.

The quick-opening "pop" valve was a solution to this. Their construction was simple: the existing circular plug valve was changed to an inverted "top hat" shape, with an enlarged upper diameter. They fitted into a stepped seat of two matching diameters. When closed, the steam pressure acted only on the crown of the top hat, and was balanced by the spring force. Once the valve opened a little, steam could pass the lower seat and began to act on the larger brim. This greater area overwhelmed the spring force and the valve flew completely open with a "pop". Escaping steam on this larger diameter also held the valve open until pressure had dropped below that at which it originally opened, providing hysteresis.

These valves coincided with a change in firing behaviour. Rather than demonstrating their virility by always showing a feather at the valve, firemen now tried to avoid noisy blowing off, especially around stations or under the large roof of a major station. This was mostly at the behest of stationmasters, but firemen also realised that any blowing off through a pop valve wasted several pounds of boiler pressure; estimated at 20 psi lost and 16 lbs or more of shovelled coal.

Pop valves derived from Adams"s patent design of 1873, with an extended lip. R. L. Ross"s valves were patented in 1902 and 1904. They were more popular in America at first, but widespread from the 1920s on.

Although showy polished brass covers over safety valves had been a feature of steam locomotives since Stephenson"s day, the only railway to maintain this tradition into the era of pop valves was the GWR, with their distinctive tapered brass safety valve bonnets and copper-capped chimneys.

Developments in high-pressure water-tube boilers for marine use placed more demands on safety valves. Valves of greater capacity were required, to vent safely the high steam-generating capacity of these large boilers.Naylor valve) became more critical.distilled feedwater and also a scouring of the valve seats, leading to wear.

High-lift safety valves are direct-loaded spring types, although the spring does not bear directly on the valve, but on a guide-rod valve stem. The valve is beneath the base of the stem, the spring rests on a flange some height above this. The increased space between the valve itself and the spring seat allows the valve to lift higher, further clear of the seat. This gives a steam flow through the valve equivalent to a valve one and a half or twice as large (depending on detail design).

The Cockburn Improved High Lift design has similar features to the Ross pop type. The exhaust steam is partially trapped on its way out and acts on the base of the spring seat, increasing the lift force on the valve and holding the valve further open.

To optimise the flow through a given diameter of valve, the full-bore design is used. This has a servo action, where steam through a narrow control passage is allowed through if it passes a small control valve. This steam is then not exhausted, but is passed to a piston that is used to open the main valve.

There are safety valves known as PSV"s and can be connected to pressure gauges (usually with a 1/2" BSP fitting). These allow a resistance of pressure to be applied to limit the pressure forced on the gauge tube, resulting in prevention of over pressurisation. the matter that has been injected into the gauge, if over pressurised, will be diverted through a pipe in the safety valve, and shall be driven away from the gauge.

There is a wide range of safety valves having many different applications and performance criteria in different areas. In addition, national standards are set for many kinds of safety valves.

Safety valves are required on water heaters, where they prevent disaster in certain configurations in the event that a thermostat should fail. Such a valve is sometimes referred to as a "T&P valve" (Temperature and Pressure valve). There are still occasional, spectacular failures of older water heaters that lack this equipment. Houses can be leveled by the force of the blast.

Pressure cookers usually have two safety valves to prevent explosions. On older designs, one is a nozzle upon which a weight sits. The other is a sealed rubber grommet which is ejected in a controlled explosion if the first valve gets blocked. On newer generation pressure cookers, if the steam vent gets blocked, a safety spring will eject excess pressure and if that fails, the gasket will expand and release excess pressure downwards between the lid and the pan. Also, newer generation pressure cookers have a safety interlock which locks the lid when internal pressure exceeds atmospheric pressure, to prevent accidents from a sudden release of very hot steam, food and liquid, which would happen if the lid were to be removed when the pan is still slightly pressurised inside (however, the lid will be very hard or impossible to open when the pot is still pressurised).

Safety valves or pressure relief valves are pressure regulating devices that are responsible for expelling excess pressure from the system when the maximum pressure levels for which they have been designed are exceeded, usually due to a

Safety valves perform their function when the pressure of the system where the fluid is contained, becomes higher than the maximum set pressure of the valve previously adjusted. When the system pressure is higher than the valve’s set

pressure, this opens, releasing the excess pressure to the atmosphere or to containment tanks, depending on the toxicity of the fluid. After releasing the excess, the valve closes again and the system pressure returns to normal.

To ensure total safety of personnel and installation, make sure that the valves have passed all safety tests and meet the requirements of the system where they are to be installed. All our valves are supplied with certificates of materials, cas-

What is the difference between the instantaneous full opening safety valve AIT (PSV) and the normal opening relief valve AN or progressive opening relief valve AP (PRV)?

The Pressure Safety Valve (PSV) opens instantaneously and fully upon reaching the set pressure for which it is designed, expelling the excess pressure from the system immediately. They are optimised for use with steam or gases.

In contrast, the normally or progressively opening Pressure Relief Valve (PRV) opens gradually as the system pressure rises above the set pressure of the valve above its setting. They are optimised to work with liquids.

At VYC Industrial we are specialists in the design and manufacture of all types of safety valves. We have a wide range of safety valves to cover all the needs of the sector.

The Mod. 496 EN safety valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The Mod. 495 EN pressure relief valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The relief valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open, at the fi rst proportional to the pressure increase, and after instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open, at the fi rst proportional to the pressure increase, and after instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open, at the fi rst proportional to the pressure increase, and after instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open proportional to the pressure increase.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open proportional to the pressure increase.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

The valve works as an automatic pressure releasing regulator activated by the static pressure existing at the entrance to the valve and is characterized by its ability to open instantly and totally.

They are used in places such as power, chemical and petrochemical plants to discharge safety valves, control valves, etc. in pressure lines and equipment that convey compressible substances such as steam, air, carbon dioxide, helium, methane, nitrogen, oxygen and other gases.

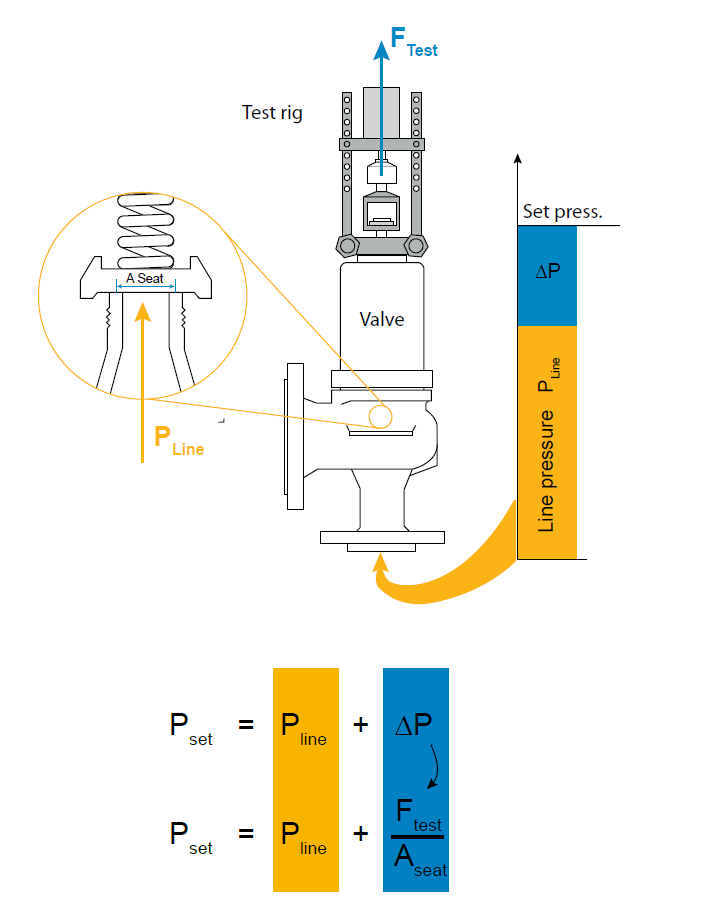

Test bench for regular inspections and setting and resetting safety valves. Ideal for distributors, maintenance companies or with in-house maintenance. It allows safety valves to be adjusted, tested and/or checked to the test pressure (setting) Pe wile cold (simulating service conditions), matching the opening pressure Ps and the closing pressure Pc, in accordance with the standard regulations.

Controlled safety pressure relief system CSPRS valves are mainly used where conventional direct-loaded spring action valves cannot guarantee the opening and closing margins that certain specifi c conditions of service demand.

The objective is to help the closure by means of pressure so that the valve remains completely watertight until reaching the set pressure and/or to activate the opening with pressure.

Increase the operating pressure of the system up to 99.9% of the set pressure.The control safety pressure relief system CSPRS device can be used with any safety valve available in the market and in particular, with models VYC Mod. 485, 486, 494, 495 and 496.

Relief valves are designed to open at a preset pressure (or temperature) level and relieve the system when it has exceeded the desired level. The valve"s relief of elevated liquid, gas, or steam pressures prevents damage to the system. We offer a wide selection of relief valves for any application.

8613371530291

8613371530291