conventional safety valve free sample

In order to ensure that the maximum allowable accumulation pressure of any system or apparatus protected by a safety valve is never exceeded, careful consideration of the safety valve’s position in the system has to be made. As there is such a wide range of applications, there is no absolute rule as to where the valve should be positioned and therefore, every application needs to be treated separately.

A common steam application for a safety valve is to protect process equipment supplied from a pressure reducing station. Two possible arrangements are shown in Figure 9.3.3.

The safety valve can be fitted within the pressure reducing station itself, that is, before the downstream stop valve, as in Figure 9.3.3 (a), or further downstream, nearer the apparatus as in Figure 9.3.3 (b). Fitting the safety valve before the downstream stop valve has the following advantages:

• The safety valve can be tested in-line by shutting down the downstream stop valve without the chance of downstream apparatus being over pressurised, should the safety valve fail under test.

• When setting the PRV under no-load conditions, the operation of the safety valve can be observed, as this condition is most likely to cause ‘simmer’. If this should occur, the PRV pressure can be adjusted to below the safety valve reseat pressure.

Indeed, a separate safety valve may have to be fitted on the inlet to each downstream piece of apparatus, when the PRV supplies several such pieces of apparatus.

• If supplying one piece of apparatus, which has a MAWP pressure less than the PRV supply pressure, the apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve, preferably close-coupled to its steam inlet connection.

• If a PRV is supplying more than one apparatus and the MAWP of any item is less than the PRV supply pressure, either the PRV station must be fitted with a safety valve set at the lowest possible MAWP of the connected apparatus, or each item of affected apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve.

• The safety valve must be located so that the pressure cannot accumulate in the apparatus viaanother route, for example, from a separate steam line or a bypass line.

It could be argued that every installation deserves special consideration when it comes to safety, but the following applications and situations are a little unusual and worth considering:

• Fire - Any pressure vessel should be protected from overpressure in the event of fire. Although a safety valve mounted for operational protection may also offer protection under fire conditions,such cases require special consideration, which is beyond the scope of this text.

• Exothermic applications - These must be fitted with a safety valve close-coupled to the apparatus steam inlet or the body direct. No alternative applies.

• Safety valves used as warning devices - Sometimes, safety valves are fitted to systems as warning devices. They are not required to relieve fault loads but to warn of pressures increasing above normal working pressures for operational reasons only. In these instances, safety valves are set at the warning pressure and only need to be of minimum size. If there is any danger of systems fitted with such a safety valve exceeding their maximum allowable working pressure, they must be protected by additional safety valves in the usual way.

In order to illustrate the importance of the positioning of a safety valve, consider an automatic pump trap (see Block 14) used to remove condensate from a heating vessel. The automatic pump trap (APT), incorporates a mechanical type pump, which uses the motive force of steam to pump the condensate through the return system. The position of the safety valve will depend on the MAWP of the APT and its required motive inlet pressure.

This arrangement is suitable if the pump-trap motive pressure is less than 1.6 bar g (safety valve set pressure of 2 bar g less 0.3 bar blowdown and a 0.1 bar shut-off margin). Since the MAWP of both the APT and the vessel are greater than the safety valve set pressure, a single safety valve would provide suitable protection for the system.

Here, two separate PRV stations are used each with its own safety valve. If the APT internals failed and steam at 4 bar g passed through the APT and into the vessel, safety valve ‘A’ would relieve this pressure and protect the vessel. Safety valve ‘B’ would not lift as the pressure in the APT is still acceptable and below its set pressure.

It should be noted that safety valve ‘A’ is positioned on the downstream side of the temperature control valve; this is done for both safety and operational reasons:

Operation - There is less chance of safety valve ‘A’ simmering during operation in this position,as the pressure is typically lower after the control valve than before it.

Also, note that if the MAWP of the pump-trap were greater than the pressure upstream of PRV ‘A’, it would be permissible to omit safety valve ‘B’ from the system, but safety valve ‘A’ must be sized to take into account the total fault flow through PRV ‘B’ as well as through PRV ‘A’.

A pharmaceutical factory has twelve jacketed pans on the same production floor, all rated with the same MAWP. Where would the safety valve be positioned?

One solution would be to install a safety valve on the inlet to each pan (Figure 9.3.6). In this instance, each safety valve would have to be sized to pass the entire load, in case the PRV failed open whilst the other eleven pans were shut down.

If additional apparatus with a lower MAWP than the pans (for example, a shell and tube heat exchanger) were to be included in the system, it would be necessary to fit an additional safety valve. This safety valve would be set to an appropriate lower set pressure and sized to pass the fault flow through the temperature control valve (see Figure 9.3.8).

A safety valve must always be sized and able to vent any source of steam so that the pressure within the protected apparatus cannot exceed the maximum allowable accumulated pressure (MAAP). This not only means that the valve has to be positioned correctly, but that it is also correctly set. The safety valve must then also be sized correctly, enabling it to pass the required amount of steam at the required pressure under all possible fault conditions.

Once the type of safety valve has been established, along with its set pressure and its position in the system, it is necessary to calculate the required discharge capacity of the valve. Once this is known, the required orifice area and nominal size can be determined using the manufacturer’s specifications.

In order to establish the maximum capacity required, the potential flow through all the relevant branches, upstream of the valve, need to be considered.

In applications where there is more than one possible flow path, the sizing of the safety valve becomes more complicated, as there may be a number of alternative methods of determining its size. Where more than one potential flow path exists, the following alternatives should be considered:

This choice is determined by the risk of two or more devices failing simultaneously. If there is the slightest chance that this may occur, the valve must be sized to allow the combined flows of the failed devices to be discharged. However, where the risk is negligible, cost advantages may dictate that the valve should only be sized on the highest fault flow. The choice of method ultimately lies with the company responsible for insuring the plant.

For example, consider the pressure vessel and automatic pump-trap (APT) system as shown in Figure 9.4.1. The unlikely situation is that both the APT and pressure reducing valve (PRV ‘A’) could fail simultaneously. The discharge capacity of safety valve ‘A’ would either be the fault load of the largest PRV, or alternatively, the combined fault load of both the APT and PRV ‘A’.

This document recommends that where multiple flow paths exist, any relevant safety valve should, at all times, be sized on the possibility that relevant upstream pressure control valves may fail simultaneously.

The supply pressure of this system (Figure 9.4.2) is limited by an upstream safety valve with a set pressure of 11.6 bar g. The fault flow through the PRV can be determined using the steam mass flow equation (Equation 3.21.2):

Once the fault load has been determined, it is usually sufficient to size the safety valve using the manufacturer’s capacity charts. A typical example of a capacity chart is shown in Figure 9.4.3. By knowing the required set pressure and discharge capacity, it is possible to select a suitable nominal size. In this example, the set pressure is 4 bar g and the fault flow is 953 kg/h. A DN32/50 safety valve is required with a capacity of 1 284 kg/h.

Coefficients of discharge are specific to any particular safety valve range and will be approved by the manufacturer. If the valve is independently approved, it is given a ‘certified coefficient of discharge’.

This figure is often derated by further multiplying it by a safety factor 0.9, to give a derated coefficient of discharge. Derated coefficient of discharge is termed Kdr= Kd x 0.9

Critical and sub-critical flow - the flow of gas or vapour through an orifice, such as the flow area of a safety valve, increases as the downstream pressure is decreased. This holds true until the critical pressure is reached, and critical flow is achieved. At this point, any further decrease in the downstream pressure will not result in any further increase in flow.

A relationship (called the critical pressure ratio) exists between the critical pressure and the actual relieving pressure, and, for gases flowing through safety valves, is shown by Equation 9.4.2.

Overpressure - Before sizing, the design overpressure of the valve must be established. It is not permitted to calculate the capacity of the valve at a lower overpressure than that at which the coefficient of discharge was established. It is however, permitted to use a higher overpressure (see Table 9.2.1, Module 9.2, for typical overpressure values). For DIN type full lift (Vollhub) valves, the design lift must be achieved at 5% overpressure, but for sizing purposes, an overpressure value of 10% may be used.

For liquid applications, the overpressure is 10% according to AD-Merkblatt A2, DIN 3320, TRD 421 and ASME, but for non-certified ASME valves, it is quite common for a figure of 25% to be used.

Two-phase flow - When sizing safety valves for boiling liquids (e.g. hot water) consideration must be given to vaporisation (flashing) during discharge. It is assumed that the medium is in liquid state when the safety valve is closed and that, when the safety valve opens, part of the liquid vaporises due to the drop in pressure through the safety valve. The resulting flow is referred to as two-phase flow.

The required flow area has to be calculated for the liquid and vapour components of the discharged fluid. The sum of these two areas is then used to select the appropriate orifice size from the chosen valve range. (see Example 9.4.3)

The primary purpose of a safety valve is to protect life, property and the environment. Safety valves are designed to open and release excess pressure from vessels or equipment and then close again.

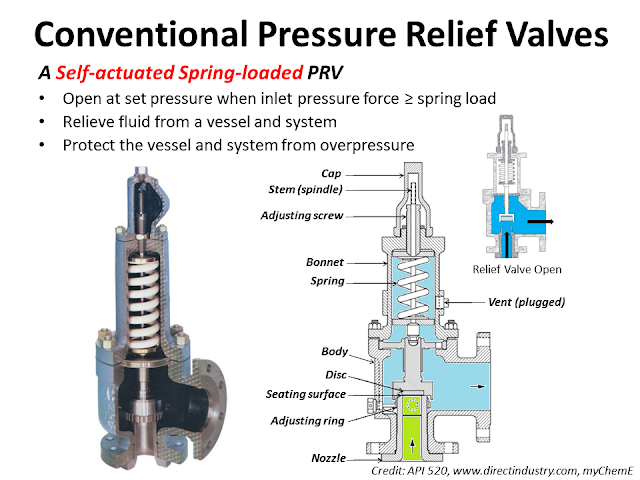

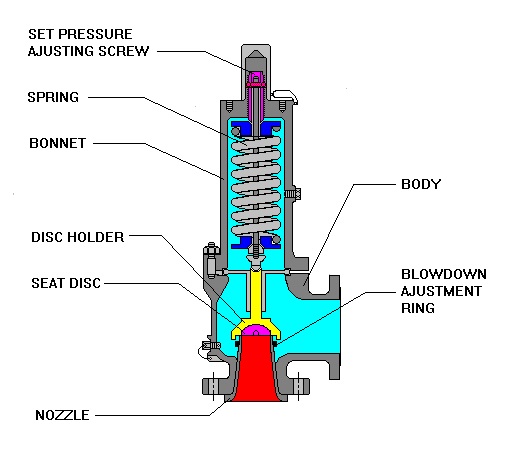

The function of safety valves differs depending on the load or main type of the valve. The main types of safety valves are spring-loaded, weight-loaded and controlled safety valves.

Regardless of the type or load, safety valves are set to a specific set pressure at which the medium is discharged in a controlled manner, thus preventing overpressure of the equipment. In dependence of several parameters such as the contained medium, the set pressure is individual for each safety application.

A little product education can make you look super smart to customers, which usually means more orders for everything you sell. Here’s a few things to keep in mind about safety valves, so your customers will think you’re a genius.

A safety valve is required on anything that has pressure on it. It can be a boiler (high- or low-pressure), a compressor, heat exchanger, economizer, any pressure vessel, deaerator tank, sterilizer, after a reducing valve, etc.

There are four main types of safety valves: conventional, bellows, pilot-operated, and temperature and pressure. For this column, we will deal with conventional valves.

A safety valve is a simple but delicate device. It’s just two pieces of metal squeezed together by a spring. It is passive because it just sits there waiting for system pressure to rise. If everything else in the system works correctly, then the safety valve will never go off.

A safety valve is NOT 100% tight up to the set pressure. This is VERY important. A safety valve functions a little like a tea kettle. As the temperature rises in the kettle, it starts to hiss and spit when the water is almost at a boil. A safety valve functions the same way but with pressure not temperature. The set pressure must be at least 10% above the operating pressure or 5 psig, whichever is greater. So, if a system is operating at 25 psig, then the minimum set pressure of the safety valve would be 30 psig.

Most valve manufacturers prefer a 10 psig differential just so the customer has fewer problems. If a valve is positioned after a reducing valve, find out the max pressure that the equipment downstream can handle. If it can handle 40 psig, then set the valve at 40. If the customer is operating at 100 psig, then 110 would be the minimum. If the max pressure in this case is 150, then set it at 150. The equipment is still protected and they won’t have as many problems with the safety valve.

Here’s another reason the safety valve is set higher than the operating pressure: When it relieves, it needs room to shut off. This is called BLOWDOWN. In a steam and air valve there is at least one if not two adjusting rings to help control blowdown. They are adjusted to shut the valve off when the pressure subsides to 6% below the set pressure. There are variations to 6% but for our purposes it is good enough. So, if you operate a boiler at 100 psig and you set the safety valve at 105, it will probably leak. But if it didn’t, the blowdown would be set at 99, and the valve would never shut off because the operating pressure would be greater than the blowdown.

All safety valves that are on steam or air are required by code to have a test lever. It can be a plain open lever or a completely enclosed packed lever.

Safety valves are sized by flow rate not by pipe size. If a customer wants a 12″ safety valve, ask them the flow rate and the pressure setting. It will probably turn out that they need an 8×10 instead of a 12×16. Safety valves are not like gate valves. If you have a 12″ line, you put in a 12″ gate valve. If safety valves are sized too large, they will not function correctly. They will chatter and beat themselves to death.

Safety valves need to be selected for the worst possible scenario. If you are sizing a pressure reducing station that has 150 psig steam being reduced to 10 psig, you need a safety valve that is rated for 150 psig even though it is set at 15. You can’t put a 15 psig low-pressure boiler valve after the reducing valve because the body of the valve must to be able to handle the 150 psig of steam in case the reducing valve fails.

The seating surface in a safety valve is surprisingly small. In a 3×4 valve, the seating surface is 1/8″ wide and 5″ around. All it takes is one pop with a piece of debris going through and it can leak. Here’s an example: Folgers had a plant in downtown Kansas City that had a 6×8 DISCONTINUED Consolidated 1411Q set at 15 psig. The valve was probably 70 years old. We repaired it, but it leaked when plant maintenance put it back on. It was after a reducing valve, and I asked him if he played with the reducing valve and brought the pressure up to pop the safety valve. He said no, but I didn’t believe him. I told him the valve didn’t leak when it left our shop and to send it back.

If there is a problem with a safety valve, 99% of the time it is not the safety valve or the company that set it. There may be other reasons that the pressure is rising in the system before the safety valve. Some ethanol plants have a problem on starting up their boilers. The valves are set at 150 and they operate at 120 but at startup the pressure gets away from them and there is a spike, which creates enough pressure to cause a leak until things get under control.

If your customer is complaining that the valve is leaking, ask questions before a replacement is sent out. What is the operating pressure below the safety valve? If it is too close to the set pressure then they have to lower their operating pressure or raise the set pressure on the safety valve.

Is the valve installed in a vertical position? If it is on a 45-degree angle, horizontal, or upside down then it needs to be corrected. I have heard of two valves that were upside down in my 47 years. One was on a steam tractor and the other one was on a high-pressure compressor station in the New Mexico desert. He bought a 1/4″ valve set at 5,000 psig. On the outlet side, he left the end cap in the outlet and put a pin hole in it so he could hear if it was leaking or not. He hit the switch and when it got up to 3,500 psig the end cap came flying out like a missile past his nose. I told him to turn that sucker in the right direction and he shouldn’t have any problems. I never heard from him so I guess it worked.

If the set pressure is correct, and the valve is vertical, ask if the outlet piping is supported by something other than the safety valve. If they don’t have pipe hangers or a wall or something to keep the stress off the safety valve, it will leak.

There was a plant in Springfield, Mo. that couldn’t start up because a 2″ valve was leaking on a tank. It was set at 750 psig, and the factory replaced it 5 times. We are not going to replace any valves until certain questions are answered. I was called to solve the problem. The operating pressure was 450 so that wasn’t the problem. It was in a vertical position so we moved on to the piping. You could tell the guy was on his cell phone when I asked if there was any piping on the outlet. He said while looking at the installation that he had a 2″ line coming out into a 2×3 connection going up a story into a 3×4 connection and going up another story. I asked him if there was any support for this mess, and he hung up the phone. He didn’t say thank you, goodbye, or send me a Christmas present.

Operational characteristics of this pressure relief valve are directly affected by back pressure changes. For conventional safety relief valve, only the superimposed back pressure affects the opening characteristic and set pressure value, but the combined back pressure (superimposed backpressure plus built up backpressure) affects the blowdown characteristic and re-seat pressure value. A conventional pressure relief valve is not used when the built-up backpressure is greater than 10% of the set pressure at 10% overpressure. A higher maximum allowable built-up backpressure may be used for overpressure greater than 10%.

Advantages of conventional relief valves are reliability and versatility. These relief valves are most reliable when sized properly and can be used in a wide range of services.

Disadvantage of these relief valves is the effect of backpressure on the relieving pressure of valve and hence pressure accumulation in the protected equipment. Also for high built up backpressure values generated by higher pressure loss in the relief valve discharge line, chattering can occur in these relief valves.

Effect of back pressure on the operational characteristics of the valve is minimized by incorporating bellows. The bellows encircle an area equal to the inlet orifice area. This area is maintained free from the effect of back pressure from the discharge side of the relief valve. The space enclosed by bellows is freely vented to air. Thus the opposing pressure on the inlet fluid is generated by the spring alone without contribution from any sort of backpressure. For these relief valves allowable back pressure is 10 - 50% of the set pressure.

Advantage of using balanced bellows relief valves is no effect of back pressure on the relieving pressure and pressure accumulation. The spring is isolated from discharge fluid from the bellows, hence risk of corrosion mitigated. These relief valves get special consideration when there is high combined backpressure on the relief valve.

In pilot operated setup, main relief is combined with and controlled by a smaller self actuated pilot valve. This relief valve valve uses the process fluid itself, circulated through a pilot valve, to apply the closing force on the safety valve disc. The pilot valve is itself a small safety valve with a spring. The main valve does not have a spring but is controlled by the process fluid from pilot valve. This arrangement allows operation of pilot operated valves with a very narrow margin between set pressure of the relief valve and operating pressure of the protected equipment. Hence these relief valves are particularly used for services where relief valve inlet line pressure drop is high (typically higher than 3% of set point) or when back pressure is high. Allowable back pressure is typically more than 50% of the set pressure.

Disadvantage of using pilot operated relief valves can be blockage of the pilot valve inlet outlet tubing by foreign matter such as hydrate, ice, wax etc.

When selecting a pressure relief valve (PRV) for any application, many factors need to be taken into consideration. One of the most important — and least well understood — is back pressure. This article explains what back pressure is and how it affects the performance of PRVs.

Superimposed back pressure. Superimposed pressure is the pressure in the discharge header before the pressure relief valve opens. Depending on the system, superimposed back pressure can be constant or variable.

Back pressure can significantly affect a valve’s performance by reducing both its set pressure and its capacity. Too much back pressure can result in chatter (rapid opening and closing), which can damage the valve.

For conventional relief valves, back pressure reduces set pressure directly on a one-to-one basis. For example, a valve with a set point at 100 psig that is subjected to 10 psig of back pressure will not reach set point until the system pressure reaches 110 psig. In this example, if the set point is not adjusted to compensate for the back pressure, this can mean that valves are operating at a level that is higher than their maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP).

The effect of back pressure on valve capacity is much more significant. Typically, high back pressure can decrease the PRV’s capacity by approximately 50%.

For balanced bellows relief valves, the bellows mitigate the effects of back pressure up to a certain point. These valves are generally not affected unless the back pressure exceeds 30 or 35% of set pressure. The tradeoff is that they can fail at higher pressures.

Back pressure needs to be accounted for when sizing a PRV. In general, back pressure should notexceed 10% of the set pressure, especially for conventional relief valves.

The key to handling back pressure is to take it into consideration when sizing and selecting your valves. If you know that the back pressure in your system will be higher than the recommended limits, you may need to select a larger valve.

Don’t risk damage to your valves or other equipment caused by too much back pressure. Contact us for assistance selecting the right valve for your application.

8613371530291

8613371530291