define safety valve theory price

The Supreme Court has reinforced the theory of the First Amendment as a "safety valve," reasoning that citizens who are free to to express displeasure against government through peaceful protest will be deterred from undertaking violent means. The boundary between what is peaceful and what is violent is not always clear. For example, in this 1965 photo, Alabama State College students participated in a non-violent protest for voter rights when deputies confronted them anyway, breaking up the gathering. (AP Photo/Perry Aycock, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Under the safety valve rationale, citizens are free to make statements concerning controversial societal issues to express their displeasure against government and its policies. In assuming this right, citizens will be deterred from undertaking violent means to draw attention to their causes.

The First Amendment, in safeguarding freedom of speech, religion, peaceable assembly, and a right to petition government, embodies the safety valve theory.

These and other decisions rest on the idea that it is better to allow members of the public to judge ideas for themselves and act accordingly than to have the government act as a censure. The Court has even shown support in cases concerning obscenity or speech that incites violent action. The safety valve theory suggests that such a policy is more likely to lead to civil peace than to civil disruption.

Justice Louis D. Brandeis recognized the potential for the First Amendment to serve as a safety valve in his concurring opinion in Whitney v. California (1927) when he wrote: “fear breeds repression; . . . repression breeds hate; . . . hate menaces stable government; . . . the path of safety lies in the opportunity to discuss freely supposed grievances and proposed remedies; and the fitting remedy for evil counsels is good ones.”

The safety valve theory was a theory about how to deal with unemployment which gave rise to the Homestead Act of 1862 in the United States. Given the concentration of immigrants (and population) on the Eastern coast, it was hypothesized that making free land available in the West would relieve the pressure for employment in the East. By analogy with steam pressure (= the need for work), the enactment of a free land law, it was believed, would act as a safety valve. This theory meant that if the East started filling up with immigrants, they could always go West until they reached a point where they could not move any farther.

A distinction has to be made between (1) the safety valve theory as an ideal and (2) the safety valve theory as embodied in the Homestead Act of 1862.

There is a dispute whether and to what extent the Homestead Act did or did not succeed as a safety valve in ameliorating the problem of unemployment in the East.

Hume’s involvement gave rise to a lot of conspiracies relating to origin of Congress. Controversy was created by W. C. Banerjee statement that Hume was acting under Lord Dufferin. R. P. Dutt analysed that the Congress was formed under a British viceroy to act as a safety valve against popular discontent. This theory originated from William Wedderburn ‘s biography of Hume published in 1913. He wrote that in 1878 Hume came across seven volumes of secret reports showing discontent among the lower classes and conspiracy to overthrow British rule. He met Lord Dufferin and they decided to form an organisation with educated Indians serving as a safety valve by opening up a communication between rulers and the ruled preventing mass revolution.

The imperialist historians discredited Congress as being a creation of the British. Marxist historians used it to build up a conspiracy theory. R. P. Dutt argued that Congress was born out of a conspiracy of the British to end any possibilities of an uprising and bourgeois leaders were a part of it. This conspiracy theory is discredited by opening of Dufferin s private papers revealed that no one in ruling circles took Humes predictions of chaos seriously as Sumit Sarkar points out. This was also proved wrong as there was no evidence found of the existence of the seven volumes of secret report in any archives of either India or London. Dufferin criticised Congress as representing only a microscopic minority and this statement shuns the safety valve conspiracy theory. Historians like Bipan Chandra have called the seven volume report a fiction.

Since 1935 there has been a growing suspicion among historians that the venerable theory of free land as a safety valve for industrial labor is dead. Out of respect for the departed one even the newer textbooks on American history have begun to maintain silence on the subject. For generations the hypothesis had such a remarkable vitality that a dwindling remnant of the old guard still profess that they observe some stirrings of life in the assumed cadaver. Consequently, it seems that the time has arrived for the reluctant pathologist to don his gas mask and, regardless of the memphitis, analyze the contents of the internal organs. Are the stirrings in the body an evidence of continued animation, or merely of gaseous and helminthic activity? Before the corpse is given a respectable burial this fact must be ascertained beyond any possible doubt.

There can be no question as to the venerable age of the decedent. Thomas Skidmore foretold him as early as 1829 in The Rights of Man to Property! George Henry Evans and his fellow agrarians of the 1840s labored often and long in eulogy of the virtues of the safety valve they were trying to bring into existence. The Working Man"s Advocate of July 6, 1844, demanded the realization of "the right of the people to the soil" and said:

Long before Frederick Jackson Turner tacitly admitted the validity of the theory,2 even the name "safety valve" had become a middle-class aphorism. The idea was so old and so generally

question. The Republican Party had so long made political capital of the Homestead Act and its feeble accomplishments that the benefit to the industrial laborer had become an axiom of American thought. Turner, himself, made only incidental use of the theory as a further illustration of his general philosophy concerning the West. Apparently he made no effort to examine the basis of the safety-valve assumption. Had he done so, no doubt the theory would have been declared dead forty or fifty years ago, and the present autopsy would have been made unnecessary. It was some of the followers of Turner who made a fetish of the assumption, but in recent years few if any have gone so far as to say that Eastern laborers in large numbers actually succeeded as homesteaders.

The approach has been shifted. An early variation of the theme was that the West as a whole, if not free land alone, provided the safety valve.3 This, as will be seen, was no more valid than the original theory. Another idea, sometimes expressed but apparently not yet reduced to a reasoned hypothesis, is that land, in its widest definition (that is, total natural resources), constituted a safety valve. This is merely one way of begging the question by proposing a new one. Besides, it is easy to demonstrate that as new natural resources were discovered the world population multiplied to take advantage of them and that the old problems were quickly transplanted to a new locality. It can readily be shown that the monopolization of these resources prevented their widest social utilization and that the pressure of labor difficulties was no less intense in new communities than in the old. Witness the Coeur d"Alene strike in Idaho in the same year as the Homestead strike in Pennsylvania. But the natural-resources-safety-valve theory will require a thorough statement and exposition by one of its adherents before an examination can be made. The manufacture of such a hypothesis will be a tough problem, in view of the fact that, ever since the development of the factory system in America, labor unrest has resulted in violently explosive strikes rather than a

gentle pop-oft of steam through any supposed safety valve. The question will have to be answered: If any safety valve existed why did it not work? Since it did not work, how can it by any twist of the imagination be called a valve at all?

Another turn of the argument is a revival of the supposition of Carter Goodrich and Sol Davison (further expounded) that while no great number of industrial laborers became homesteaders, yet the safety valve existed, because it drained off the surplus of the Eastern farm population that otherwise would have gone to the cities for factory jobs. So, free land was a safety valve because it drew potential industrial labor to the West.4

Again, the question immediately arises: Why did this potential safety valve not work? Was it really a safety valve at all or was it merely a "whistle on a peanut roaster"? There can be no confusion of definitions involved. There is only one definition of the term: "An automatic escape or relief valve for a steam boiler, hydraulic system, etc." Under the catch-all "etc." one may just as well include "labor unrest." Obviously the safety valve is not for the benefit of the steam, water, or labor that escapes from the boiler, hydraulic system, or factory. It is to prevent the accumulation of pressure that might cause an explosion.

A safety valve is of use only when pressure reaches the danger point. This is where the trouble comes with the labor safety valve in all of its interpretations. It certainly was not working at the time of the Panic of 1837, or in the depression following the Panic of 1873, when over a million unemployed workmen paced the streets and knew that free lands were beyond their reach. It was rusted solid and immovable during the bloody railroad strikes of 1877 and the great labor upheaval of the 1880s. When the old-time Mississippi River steamboat captain "hung a nigger" on the arm of the safety valve when running a race, it can be positively asserted that his safety valve as such did not exist. This belief would doubtless be shared by the possible lone survivor picked maimed and scalded off a sycamore limb after the explosion.

fortunate laborers could and did take up land. But this seepage of steam which went on almost constantly did not prevent the pressure from rising when too much fuel was put under the boiler, and the seepage almost stopped entirely whenever the pressure got dangerously high. It was not till the 1830s, when the factory system in America began to bloom and the labor gangs were recruited for the building of canals and railroads, that any situation arose which would call for a safety valve. The shoemaker or carpenter of colonial days who turned to farming did not do so as a release from an ironclad wage system, as millions between 1830 and 1900 would have liked to do if they could. It was an era of slipshod economy and easy readjustment, where no great obstacle was put in the way of misfits. Even if one admits that a scarcity of free labor for hire was one of the minor reasons for the late development of a factory system, and that the choice of close and cheap land kept down the supply, yet a far greater reason was the scarcity of manufacturing capital. When the factory system began, it was easy to import shiploads of immigrant laborers. The same could have been done a generation or two earlier if there had been the demand.

But perhaps a more substantial argument is needed to answer so attractive a hypothesis as that of the potential safety valve. At first glance this new idea has some charm. Certainly the Western farms did not create their own population by spontaneous generation. If not Eastern industrial laborers, then undoubtedly Eastern farmers must have supplied the initial impulse, and each Eastern farmer who went west drained the Eastern potential labor market by one. But the question is: Did all the migration from East to West amount to enough to constitute a safety valve for Eastern labor? Did not the promise of free land, and such migration as actually occurred, simply lure million of Europeans to American shores, seeking farms or industrial jobs, the bulk of the newcomers remaining in the East to make possible a worse labor congestion than would have existed if everything west of the Mississippi River had been nonexistent The answer is so simple that it can be evolved from census data alone. The post mortem can now be held. If a sufficient domestic migration did take place with the desired results, then there was a safety valve, and there is no corpse of a theory to examine. If not, then the theory is dead and the body can be laid to rest.

surplus of farm population developed and where did it settle between 1860 (just before the Homestead Act) and 1900 (by which date the last gasp of steam is admitted to have escaped from the safety valve)? Here close estimates must substitute for an actual count, for before 1920 the census did not distinguish between actual farm and nonfarm residence. But the census officials did gather and publish figures on the numbers of persons employed for gain in the different occupations, and, wherever comparisons can be made, it is noticeable that the ratio of farm workers to all other persons receiving incomes has always been relatively close to the ratio between total farm and nonfarm population. On this basis of calculation (the only one available and accurate enough for all ordinary needs), in forty years the farm population only expanded from 19,000,000 to 28,000,000, while the nonfarm element grew from somewhat over 12,000,000 to 48,000,000, or almost fourfold. Villages, towns, and cities gained about 18,000,000 above the average rate of growth for the Nation as a whole, while the farm increase lagged by the same amount below the average. These figures are derived from a careful analytical study of occupations, based on census reports, which shows the number of income receivers engaged in agriculture creeping from 6,287,000 to 10,699,000, while those in nonfarm occupations soared from 4,244,000 to 18,374,000.5

fraction of the increased population of the United States on such farms anywhere in the Nation, and hardly enough to consider in the West. This is not the way safety valves are constructed.

Here the potential-safety-valve advocates spoil their own argument. One of them stresses the great fecundity of Eastern farmers, "a dozen children being hardly exceptional."11 At only the average rate of breeding for the whole Nation, the 19,000,000 farm population of 1860, with their descendants and immigrant additions, would have numbered about 46,000,000 by 1900. But barely 60 percent of that number were on farms anywhere in the country at the later date, and only 7,000,000 could have been on farms owned by themselves or their families. If farmers were as philoprogenitive as just quoted, then by 1900 the number of persons

of farm ancestry must have been closer to 60,000,000 than 46,000,000, and the increase alone would amount to at least 40,000,000. But the growth of farm population was only 9,000,000, and, of these, little more than 2,000,000 could have been on farms owned by their families. If it could be assumed that all the augmentation in farm population had been by migrating native farmers, by 1900 there would have been 31,000,000 of farm background (as of 1860) residing in the villages, towns, and cities; 9,000,000 would have been on new farms or subdivisions of old ones; of these, nearly 7,000,000 would have been tenants or hired laborers and their families, depressing industrial labor by their threat of competition; and about 2,000,000 would have been on their own farms, whether "virgin soil" of the West or marginal tracts in the East. But it would be taking advantage of the opponent"s slip of the pen to trace this phantasy further. The law of averages is enough in itself to annihilate the safety valvers" contention. By the use of this conservative tool alone it will be realized that at least twenty farmers moved to town for each industrial laborer who moved to the land, and ten sons of farmers went to the city for each one who became the owner of a new farm anywhere in the Nation.

As to the farms west of the Mississippi River, it is well known that many of them were settled by aliens (witness the West North Central States with their large numbers of Scandinavians). Here is a theme that might well be expanded. The latest exponent of the potential-labor-safety-valve theory declares that "potential labor was drained out of the country, and to secure it for his fast expanding industrial enterprise, the manufacturer must import labor from Europe."14 Anyone must admit that a fraction of the surplus farm labor of the East went on new farms. But how does this additional immigrant stream into the cities affect the safety valve? The immigrants may not really have increased the industrial population. It has often been contended that, instead, the resulting competition restricted the native birth rate in equal proportion to the numbers of the newcomers. Apparently this must remain in the realm of speculation. Be this as it may, the immigrants, with their background of cheap living, acted as a drag on wages, thus making the lot of the city laborer all the harder. This is not the way that even a potential safety valve should work.

over a million, by 1900 those twenty-two States still had 6,000,000 of post-1860 immigrant stock. If the estimate for the increase of the pre-1860 element is too low, so, it can be countered, were the totals of the Census of 1900. Grandchildren were not counted, and mature immigrants of the 1860s could have had a lot of grandchildren by 1900. All the descendants of the pre-1860 immigrants were included in the estimate of 12,000,000 for the increase of the inhabitants of 1860, whereas all after the first descent are excluded from the post-1860 immigrant posterity. On the other hand let it be conceded that 12,000,000 by internal expansion and 6,000,000 by immigration, or 18,000,000 in all, is too much. This would leave only 3,000,000 of the West in 1900, or one-seventh of the total, accounted for by migration from the Eastern States. The calculator can afford to be generous. Subtract two million from the internal expansion and another million from the alien stock, and add these to the migrants from the Eastern States. Suppose, then, that 6,000,000 of the West"s population of 1900 was of pre-1860 Eastern United States origin, and three times that many foreigners and their children had come into the East to replace them. It all simmers down to the fact that the West acted as a lure to prospective European immigrants, either to take up lands, to occupy vacated city jobs, or to supply the demands of a growing industry. In any case the effect was just exactly the opposite of a safety valve, actual or potential.

all somewhat, but there were several other States that approximated the worst conditions. The percentage in Nebraska was 35.5, in Kansas 33.9, in Iowa 33.6, in Missouri 30.6, and in South Dakota 21.9.18 But, also, slightly over 40 percent of all Western farm-income receivers were wage laborers.19 If these same ratios apply to total population on the farms, then well over 1,130,000 of the Eastern element in the West were wage laborers" families; more than 989,000 were on tenant holdings; and less than 707,000 occupied farms owned by themselves. This means that there was only one person on such a family possession for each twenty-five who left the farms of the Nation in the preceding forty years. But perhaps this number is a little too small. No doubt a good number of the hired laborers were also the sons of the owners. Also, though many of the wage workers in the West lived with their families in separate huts on the farms, another considerable number were single men (or detached from their families) who boarded with the owner. How much this situation affected the given figures is uncertain. But here is something more substantial. Only 65 percent of the farms, or less than 372,000 in all, were owner-operated. Here, then, is the number of those tracts of "virgin soil" taken up and kept -- one for each forty-eight persons who left their "ancestral acres" in the East, or possibly one family farm for each ten families. What a showing for the potential safety valve!

One point remains: Urban development in its relation to safety-valve theories. Between 1790 and 1860 the percentage of persons in cities of 8,000 or more inhabitants grew from 3.3 to 16.1; the number of such places from 6 to 141; and their population from 131,000 to 5,000,000. Over half of this growth took place after 1840. The city was already draining the country. But this was only the curtain raiser for the act to follow. In the next forty years the number of cities was multiplied to 547, their inhabitants to 25,000,000, and their percentage of the total population to 32.9. They had grown more than twice as fast as the Nation at large.20 The same rule applies to all municipalities of 2,500 and over, as their population expanded from 6,500,000 to 30,400,000.21 The cities may have bred pestilence, poverty, crime,

In each decade, the Far-Western regions were well below the national ratio of agricultural to town and city labor, and to 1890 they were far below. In 1870, outside the West South Central States and Iowa, the figure averaged 44.3 percent for seventeen Western States compared with 47.4 percent for the United States. In the next twenty years, when free land was presumed to be the greatest lure of the West, the towns gained on the farms till the latter included only 46.5 percent of the Western total in spite of the still preponderantly rural character of the West South Central division. Then in 1890, according to the legend, the gate to free land flew shut with a bang, and the urban-labor safety valve rusted tight forever. Yet, the increase in agricultural population in the next ten

years was nearly a fourth larger than the average for the preceding decades. Whereas the city had been draining labor from the farm before 1890, now that the theoretical safety valve was gone the Western farm was gaining on the Western city. Good land -- free, cheap, or at speculators" prices -- undoubtedly was more abundant before 1890 than afterward. Before that date, without cavil, this land had helped keep down rural discontent and unrest. A small percentage of surplus farmers and a few other discontented ones in periods of hard times, had been able to go west and take up new farms, but many times that number to had sought refuges, however tenuous, in the cities. Whether this cityward migration left the most intelligent and energetic or the duller and more indolent back on the farm is relatively immaterial so far as the release of pressure is concerned. Such evidence as has been uncovered shows no decided weight one way or the other.

This much is certain. The industrial labor troubles of the 1870s and 1880s, when this potential safety valve was supposed to be working, were among the most violent ever experienced in the Nation"s history. Steam escaped by explosion and not through a safety valve of free land. On the other hand, down to 1890 the flow of excess farmers to the industrial centers was incessant and accelerated. When hard times settled down on the farms of the Middle West, as in the 1870s, Grangers could organize, antimonopoly parties arise, and greenbackers flourish; but the pressure was eased largely by the flow of excess population to the towns. No doubt the migrants would have done better to stay at home and create an explosion. Instead, they went to town to add to the explosive force there. Farm agitation died down when a few reforms were secured, and the continued cityward movement retarded its revival.

However, after 1890 this release for rural discontent began to fail. The cities were approaching a static condition and were losing their attraction for farmers. This condition continued until between 1930 and 1940 there was virtually no net shift of population between town and country.25 In the 1890s when the city safety valve for rural discontent was beginning to fail, the baffled farmer was at bay. Drought in the farther West and congestion in the cities left him no direction to go. He must stay on his freehold or tenant farm and fight. Populism in the 1890s was not to be as easily diverted or sidetracked by feeble concessions as had been Grangerism in the 1870s. In the forty years after 1890, the farmers, balked increasingly in their cityward yearnings, began to take far greater risks than ever before in their efforts to conquer the arid regions. Four times as much land was homesteaded as in the preceding decades.26 Great things were accomplished in the way of irrigation and dry farming; but also great distress was encountered, great dust bowls were created, and great national problems of farm relief

Generalization alone does not establish a thesis, but already there is a substantial body of facts to support an argument for the city safety valve for rural discontent. Nevertheless old stereotypes of thought die hard. Quite often they expire only with their devotees. It has been proved time after time that since 1880, at least, the old idea of the agricultural ladder has worked in reverse. Instead of tenancy being a ladder up which workers could climb to farm ownership, in reality the freeholder more often climbed down the ladder to tenancy. Yet there are people in abundance who still nourish the illusion that their old friend remains alive. There is no reason for assuming that in the present instance the truth will be any more welcome than it has proved to be in the past. There never was a free-land or even a Western safety valve for industrial labor. There never was one even of the potential sort. So far did such a valve fail to exist that the exact opposite is seen. The rapid growth of industry and commerce in the cities provided a release from surplus farm population. The safety valve that actually existed worked in entirely the opposite direction from the one so often extolled. Perhaps the growth of urban economy also, on occasion, was rapid and smooth enough to absorb most of the growing population without explosive effect. Once the people concentrated in the cities, there was no safety valve whatever that could prevent violent eruptions in depression periods. Of this, the die-hards also will remain unconvinced. The persons who mournfully sing that "The old gray mare, she ain"t what she used to be" seldom are ready to admit that she never did amount to much.

The post mortem on the theory of a free-land safety valve for industrial labor is at an end. For a century it was fed on nothing more sustaining than unsupported rationalization. Its ethereal body was able to survive on this slender nourishment as long as the supply lasted. But when the food was diluted to a "potential" consistency, it was no longer strong enough to maintain life. Death came from inanition. The body may now be sealed in its coffin and laid to rest. Let those who will consult the spirit rappers to bring forth its ghost.

Some people have proposed a “safety valve” to control the costs of a cap-and-trade policy to fight global warming. This post explains what a safety valve is, and why it provides only an illusion of cost management.

The “safety valve” or “escape hatch” is meant to address this. It specifies that when prices reach a predetermined dollar value, businesses no longer have to rely on the established supply of allowances available in the market. Instead, the federal government makes new allowances available for sale at a specified price – potentially in an unlimited quantity.

There are two problems with this approach:A safety valve destroys the cap. The hard limit on emissions is the cornerstone of a cap-and-trade policy. Without a solid cap, we can’t be sure our emissions will go down enough to avoid the worst consequences of global warming. A safety valve gives the illusion that we are controlling emissions while allowing more greenhouse gas pollution into the atmosphere.

A safety valve limits the economic opportunity of those who develop cleaner technology. Higher permit prices signal the market to invest more in innovative low-carbon technologies – happy news if you’re in the business of inventing and selling ways to cut pollution. A safety valve would sharply curtail incentive for innovation. This drives up costs in the long run, and discourages the development of the clean technology we need.

A safety valve seriously undermines the main advantages of a cap. Its ability to control costs is an illusion, it lets more pollution into the atmosphere, and discourages entrepreneurs from investing in pollution-cutting technology.

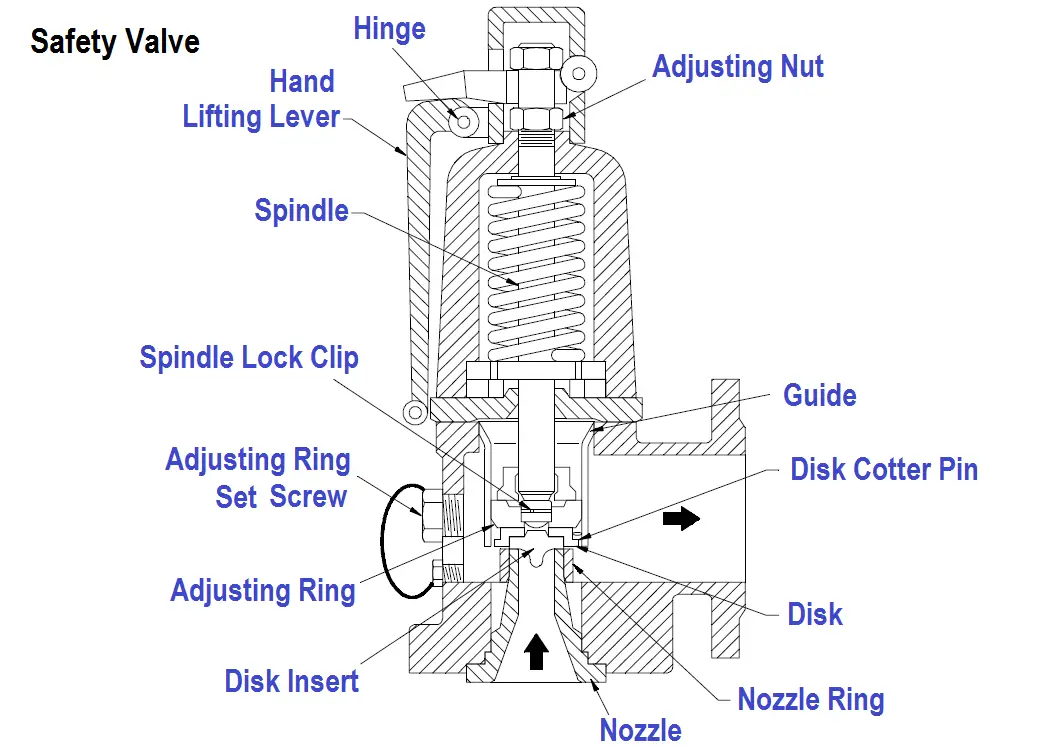

In order to ensure that the maximum allowable accumulation pressure of any system or apparatus protected by a safety valve is never exceeded, careful consideration of the safety valve’s position in the system has to be made. As there is such a wide range of applications, there is no absolute rule as to where the valve should be positioned and therefore, every application needs to be treated separately.

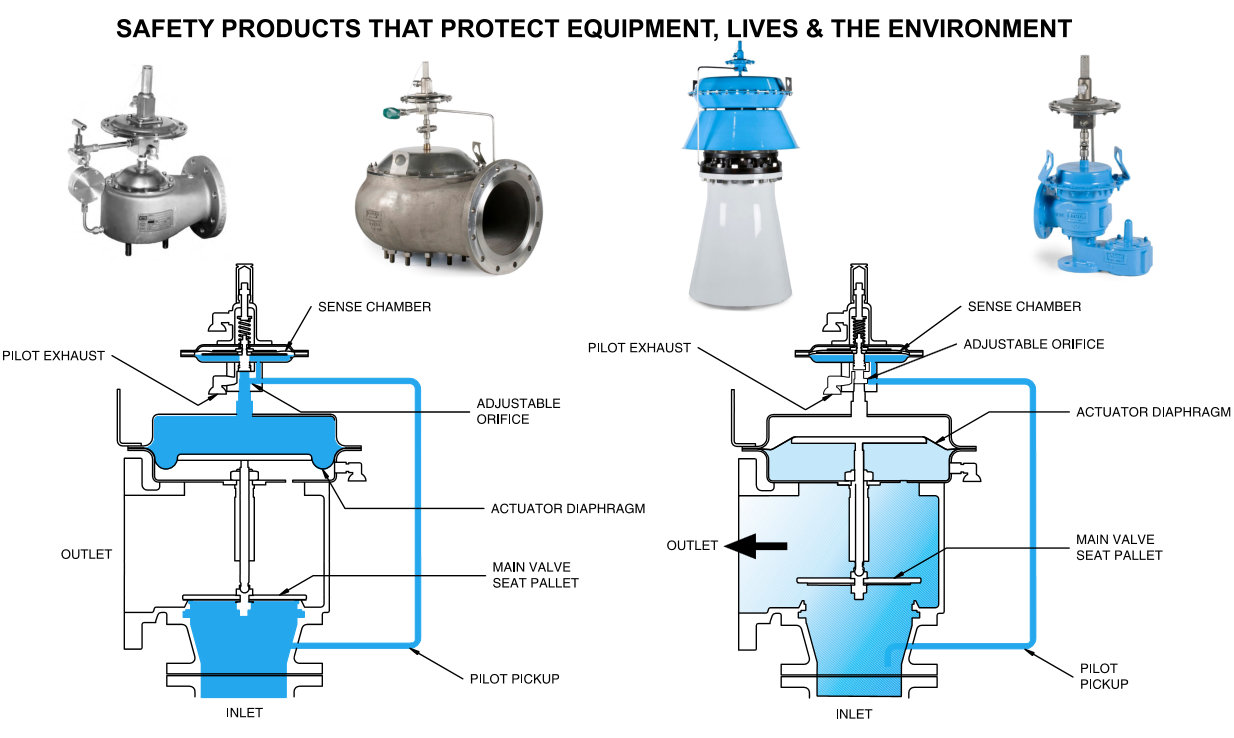

A common steam application for a safety valve is to protect process equipment supplied from a pressure reducing station. Two possible arrangements are shown in Figure 9.3.3.

The safety valve can be fitted within the pressure reducing station itself, that is, before the downstream stop valve, as in Figure 9.3.3 (a), or further downstream, nearer the apparatus as in Figure 9.3.3 (b). Fitting the safety valve before the downstream stop valve has the following advantages:

• The safety valve can be tested in-line by shutting down the downstream stop valve without the chance of downstream apparatus being over pressurised, should the safety valve fail under test.

• When setting the PRV under no-load conditions, the operation of the safety valve can be observed, as this condition is most likely to cause ‘simmer’. If this should occur, the PRV pressure can be adjusted to below the safety valve reseat pressure.

Indeed, a separate safety valve may have to be fitted on the inlet to each downstream piece of apparatus, when the PRV supplies several such pieces of apparatus.

• If supplying one piece of apparatus, which has a MAWP pressure less than the PRV supply pressure, the apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve, preferably close-coupled to its steam inlet connection.

• If a PRV is supplying more than one apparatus and the MAWP of any item is less than the PRV supply pressure, either the PRV station must be fitted with a safety valve set at the lowest possible MAWP of the connected apparatus, or each item of affected apparatus must be fitted with a safety valve.

• The safety valve must be located so that the pressure cannot accumulate in the apparatus viaanother route, for example, from a separate steam line or a bypass line.

It could be argued that every installation deserves special consideration when it comes to safety, but the following applications and situations are a little unusual and worth considering:

• Fire - Any pressure vessel should be protected from overpressure in the event of fire. Although a safety valve mounted for operational protection may also offer protection under fire conditions,such cases require special consideration, which is beyond the scope of this text.

• Exothermic applications - These must be fitted with a safety valve close-coupled to the apparatus steam inlet or the body direct. No alternative applies.

• Safety valves used as warning devices - Sometimes, safety valves are fitted to systems as warning devices. They are not required to relieve fault loads but to warn of pressures increasing above normal working pressures for operational reasons only. In these instances, safety valves are set at the warning pressure and only need to be of minimum size. If there is any danger of systems fitted with such a safety valve exceeding their maximum allowable working pressure, they must be protected by additional safety valves in the usual way.

In order to illustrate the importance of the positioning of a safety valve, consider an automatic pump trap (see Block 14) used to remove condensate from a heating vessel. The automatic pump trap (APT), incorporates a mechanical type pump, which uses the motive force of steam to pump the condensate through the return system. The position of the safety valve will depend on the MAWP of the APT and its required motive inlet pressure.

This arrangement is suitable if the pump-trap motive pressure is less than 1.6 bar g (safety valve set pressure of 2 bar g less 0.3 bar blowdown and a 0.1 bar shut-off margin). Since the MAWP of both the APT and the vessel are greater than the safety valve set pressure, a single safety valve would provide suitable protection for the system.

Here, two separate PRV stations are used each with its own safety valve. If the APT internals failed and steam at 4 bar g passed through the APT and into the vessel, safety valve ‘A’ would relieve this pressure and protect the vessel. Safety valve ‘B’ would not lift as the pressure in the APT is still acceptable and below its set pressure.

It should be noted that safety valve ‘A’ is positioned on the downstream side of the temperature control valve; this is done for both safety and operational reasons:

Operation - There is less chance of safety valve ‘A’ simmering during operation in this position,as the pressure is typically lower after the control valve than before it.

Also, note that if the MAWP of the pump-trap were greater than the pressure upstream of PRV ‘A’, it would be permissible to omit safety valve ‘B’ from the system, but safety valve ‘A’ must be sized to take into account the total fault flow through PRV ‘B’ as well as through PRV ‘A’.

A pharmaceutical factory has twelve jacketed pans on the same production floor, all rated with the same MAWP. Where would the safety valve be positioned?

One solution would be to install a safety valve on the inlet to each pan (Figure 9.3.6). In this instance, each safety valve would have to be sized to pass the entire load, in case the PRV failed open whilst the other eleven pans were shut down.

If additional apparatus with a lower MAWP than the pans (for example, a shell and tube heat exchanger) were to be included in the system, it would be necessary to fit an additional safety valve. This safety valve would be set to an appropriate lower set pressure and sized to pass the fault flow through the temperature control valve (see Figure 9.3.8).

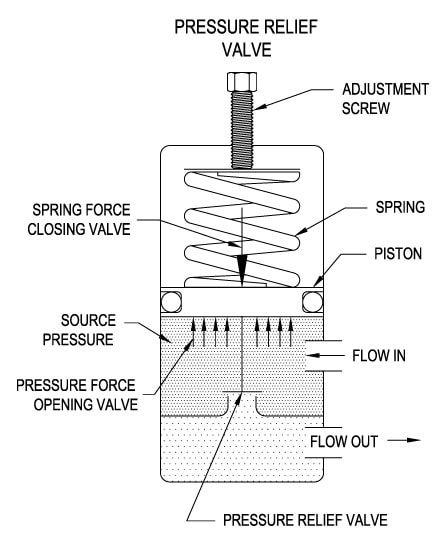

Discovering the safety device used in most industry for pressure flow control, pressure relief valve it’s called. It’s an equipment that must be found in the industry to control an over-pressurized vessel.

So, a pressure relief valve is a safety device designed to secure a pressurized system during an overpressure occurrence during operation. The system is widely available today as an electronic, pneumatic and hydraulic system. The various types serve the same purpose in different applications and are called pressure relief valve, relief valve or safety valve.

Depending on the type of system, the power source could be electricity or compressed air for operation. Since its purpose is to control the pressure so that life and properties can be safe. A pressure relief valve must be capable to serve for a long period of time and capable of operating at all times. And a professional operator with experience must be in charge to ensure proper working as there is no room for error.

Today we’ll be looking at the definition, functions, applications, working, types, components, considerations, benefits and limitations of a pressure relief valve.

A pressure relief valve or relief valve is a special type of safety valve system used to control or limit the pressure in a system. It can be manually or automatically controlled from a pressurized vessel or piping system. The pressurized fluid or gas is discharged to a reservoir or atmosphere to relieve pressure in excess of the maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP).

The primary purpose of a pressure relief valve is to protect pressure vessels or system from catastrophic failure. Catastrophic failure could be disastrous during an overpressure event, could either be liquid or gaseous.

This device is widely used in petrochemical, petroleum refining, chemical manufacturing industries. Industries where natural gas processing occurs and power generation, as well as water supply industries, also make good use of pressure relief valve. Though it’s generally known as relief valve depending on its field of application it can be called pressure relief valve (PRV), pressure safety valve (PSV), or safety valve. You should note the design and operation of these valves are slightly different.

The working of a relief valve is quite complex but can be easily understood. It consists of ball, poppet or spool opposed by a spring which is placed into a cavity or ported body. A hydraulic system is often used to limit fluid pressure in the part of the circuit they are installed.

The poppet is in the form of a disc or cone shape object that is mounted within an opposite machine seat. If the part is forced closed by spring pressure, very low leakage will be providing. The spool is a cylindrical, machined steel rod with metering grooves or notches that’s also stopped by spring pressure. It leaks more than a poppet valve but offers superior metering effects.

In the working of a relief valve, excessive pressurized fluid is provided from an open path to a tank with the purpose of reducing work port pressure. As soon as the fluid pressure begins to rise, the force is applied to the bottom of the spool or poppet. This allows the valve to open modestly at first, bleeding little fluid as required to maintain the downstream pressure. But if the downstream pressure continues to rise, the force acting upon the poppet or spool will be pushing it further towards the spring until the point spring force is balanced by the hydraulic force.

The pressure rise is as a result of load pressure combination, backpressure, and energy required to flow through the valve itself. The initial fluid force overcomes the seated force of the spring by the help of the cracking pressure. As the valve flows more fluid to the tank, the rate of pressure rise is safe because the forces of the pressurized fluid counteract the compression rate of the spring. If the valve is nearly fully open, pressure rise increases again as the valve bottom opens due to the flow forces.

As the operation or backpressure decreases, the valve begins to close. This is done at differing rates than the opening. The difference between the opening and closing curve is called its hysteresis, it’s indicative and instruction of the quality of its construction. This is because higher quality valves with advanced construction allow lower pressure rise with better hysteresis.

the conventional spring-loaded types of relief valve that contained the bonnet, spring, and guide in the released fluids. Its relief pressure backpressure decreases the set pressure if the bonnet is vented to the atmosphere. But, if the bonnet is vented internally to the outlet, the relief-system backpressure increases the set pressure.

The pilot-operated valve is controlled by an auxiliary pressure pilot. The resistance force on the piston in the main valve is achieved by the pressure during the operation through an orifice. The net seating force on the piston actually rises as the process pressure nears the set point.

a safety valve is a pressure relief valve that works by inlet static pressure and design to rapidly open with a pop action. It is widely used for air and stream services. A safety valve is available in two forms:

Full-lift safety valve: in this safety valve the disc is also automatically lifted but the actual charge area is not determined by the position of the disc.

A relief valve is a pressure relief device design with an inlet static pressure for its working. It has a gradual lift generally proportional to the increase in pressure over opening pressure. It’s suitable for close discharge system as it is enclosed in a spring housing.

A safety relief valve is a pressure relief valve characterized by its rapid opening or pop action. Also known for its opening in proportion to the increase in pressure over the opening pressure base on its application. Safety relief valves are used either for liquid or compressible fluid. The common type is the conventional and balanced safety relief valve which were earlier explained.

A power actuated pressure relief valve contained a relieving device that is joined with and controlled by a device requiring an external source of energy.

A vacuum relief valve is a pressure relief device that admits fluid to prevent an excessive internal vacuum. It’s designed to reclose so as to prevent further flow of fluid after normal conditions have been restored.

Selecting appropriate relief devices to handle the imposed loads. Several components must be put into consideration. Parts like set pressure, backpressure, dual relief valve, multiple relief valves must suit the capacity of the relieving device.

In conclusion, a pressure relief valve is a safety device used in the industrial world to save lives and properties. We saw the various types and components of pressure relief valve, how it works and also selection consideration.

8613371530291

8613371530291