first step act 2018 safety valve brands

In December 2018, President Trump signed into law the First Step Act, which mostly involves prison reform, but also includes some sentencing reform provisions.

The key provision of the First Step Act that relates to sentencing reform concerns the “safety valve” provision of the federal drug trafficking laws. The safety valve allows a court to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum sentence for the crime, and to reduce the person’s offense level under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines by two points.

The First Step Act increases the availability of the safety valve by making it easier to meet the first requirement—little prior criminal history. Before the First Step Act, a person could have no more than one criminal history point. This generally means no more than one prior conviction in the last ten years for which the person received either probation or less than 60 days of prison time.

Section 402 of the First Step Act changes this. Now, a person is eligible for the safety valve if, in addition to meeting requirements 2-5 above, the defendant does not have:

This news has been published for the above source. Kiss PR Brand Story Press Release News Desk was not involved in the creation of this content. For any service, please contact https://story.kisspr.com.

Congress changed all of that in the First Step Act. In expanding the number of people covered by the safety valve, Congress wrote that a defendant now must only show that he or she “does not have… (A) more than 4 criminal history points… (B) a prior 3-point offense… and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense.”

The “safety valve” was one of the only sensible things to come out of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the bill championed by then-Senator Joe Biden that, a quarter-century later, has been used to brand him a mass-incarcerating racist. The safety valve was intended to let people convicted of drug offenses as first-timers avoid the crushing mandatory minimum sentences that Congress had imposed on just about all drug dealing.

Eric Lopez got caught smuggling meth across the border. Everyone agreed he qualified for the safety valve except for his criminal history. Eric had one prior 3-point offense, and the government argued that was enough to disqualify him. Eric argued that the First Step Actamendment to the “safety valve” meant he had to have all three predicates: more than 4 points, one 3-point prior, and one 2-point prior violent offense.

Last week, the 9th Circuit agreed. In a decision that dramatically expands the reach of the safety valve, the Circuit applied the rules of statutory construction and held that the First Step amendment was unambiguous. “Put another way, we hold that ‘and’ means ‘and.’”

“We recognize that § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language might be viewed as a considerable departure from the prior version of § 3553(f)(1), which barred any defendant from safety-valve relief if he or she had more than one criminal-history point under the Sentencing Guidelines… As a result, § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language could possibly result in more defendants receiving safety-valve relief than some in Congress anticipated… But sometimes Congress uses words that reach further than some members of Congress may have expected… We cannot ignore Congress’s plain and unambiguous language just because a statute might reach further than some in Congress expected… Section 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language, the Senate’s own legislative drafting manual, § 3553(f)(1)’s structure as a conjunctive negative proof, and the canon of consistent usage result in only one plausible reading of § 3553(f)(1)’s“and” here: “And” is conjunctive. If Congress meant § 3553(f)(1)’s “and” to mean “or,” it has the authority to amend the statute accordingly. We do not.”

Congress changed all of that in the First Step Act. In expanding the number of people covered by the safety valve, Congress wrote that a defendant now must only show that he or she “does not have… (A) more than 4 criminal history points… (B) a prior 3-point offense… and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense.”

The “safety valve” was one of the only sensible things to come out of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the bill championed by then-Senator Joe Biden that, a quarter-century later, has been used to brand him a mass-incarcerating racist. The safety valve was intended to let people convicted of drug offenses as first-timers avoid the crushing mandatory minimum sentences that Congress had imposed on just about all drug dealing.

Eric Lopez got caught smuggling meth across the border. Everyone agreed he qualified for the safety valve except for his criminal history. Eric had one prior 3-point offense, and the government argued that was enough to disqualify him. Eric argued that the First Step Actamendment to the “safety valve” meant he had to have all three predicates: more than 4 points, one 3-point prior, and one 2-point prior violent offense.

Last week, the 9th Circuit agreed. In a decision that dramatically expands the reach of the safety valve, the Circuit applied the rules of statutory construction and held that the First Step amendment was unambiguous. “Put another way, we hold that ‘and’ means ‘and.’”

“We recognize that § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language might be viewed as a considerable departure from the prior version of § 3553(f)(1), which barred any defendant from safety-valve relief if he or she had more than one criminal-history point under the Sentencing Guidelines… As a result, § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language could possibly result in more defendants receiving safety-valve relief than some in Congress anticipated… But sometimes Congress uses words that reach further than some members of Congress may have expected… We cannot ignore Congress’s plain and unambiguous language just because a statute might reach further than some in Congress expected… Section 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language, the Senate’s own legislative drafting manual, § 3553(f)(1)’s structure as a conjunctive negative proof, and the canon of consistent usage result in only one plausible reading of § 3553(f)(1)’s“and” here: “And” is conjunctive. If Congress meant § 3553(f)(1)’s “and” to mean “or,” it has the authority to amend the statute accordingly. We do not.”

On December 21, 2018, Congress passed and President Donald Trump signed into law the FIRST STEP Act of 2018 (FSA) the first comprehensive criminal justice reform law passed in over a decade. The Act, formally called the Formerly Incarcerated Reenter Society Transformed Safely Transitioning Every Person (FIRST STEP), was the culmination of several years of bipartisan Congressional debate to address how to reduce the size of the federal prison population, reduce recidivism rates (reoffending rates), and improve conditions in federal prisons while also creating mechanisms to maintain public safety (James, 2019). The FSA has three major components: 1) correctional reform by establishing a prisoner risk and needs assessment system at the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP); 2) federal sentencing reform through changes to penalties for some federal offenses specifically sentences for non-violent drug offenses; and 3) reauthorization of the Second Chance Act of 2007 which authorizes federal funding for state and federal reentry programs to help people leaving prison reenter their communities, so that they do not reoffend referred to as recidivism reduction programs (James, 2019). In addition the FSA includes other criminal justice-related provisions to improve conditions in federal prisons and the lives of prisoners and their families while incarcerated.

The FSA requires the Department of Justice (DOJ) to develop a risk and needs assessment system to be used by BOP to assess the recidivism (the tendency of a convicted criminal to reoffend) of all federal prisoners and to place them in programs to reduce the risk. The FSA also provides essential sentencing reform by shortening mandatory minimum sentences for non-violent drug offenses. It eases a federal “three strikes” rule which currently imposes a life sentence for three or more convictions and instead issues a set 25-year sentence. Most consequentially, the FSA also expands the “safety valve” provision, which allows judges to sentence low-level, non-violent drug offenders with minor criminal histories to less than the required mandatory minimum for an offense (Grawert & Lau, 2019). The FSA also makes the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 retroactive. The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 helped reduce the sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offenses which primarily hurt racial minorities. In addition to sentencing reform, the FSA reauthorizes funds and expands grant programs to non-profits and community and faith-based organizations under the Second Chance Act to assist with prisoner reentry into society in an effort to reduce recidivism rates. Other prison reform elements are incorporated to improve prison conditions for incarcerated prisoners including eliminating inhumane treatments such as the use of restraints on pregnant women prisoners and solitary confinement; providing early release of elderly and terminally ill prisoners, and “good time credit,” small sentence reductions for good behavior (Grawert & Lau, 2019).

The FSA passed in response to demands to restore a meaningful degree of fairness to federal sentencing laws which were deemed unduly harsh and applied inconsistently and to reduce the extraordinarily large federal prison population which led to a mass incarceration crisis in the US. Also playing a central role in the increase of mass incarceration has been federal sentencing laws. In the past three decades the federal prison population has increased by more than 700 percent since 1980 and federal prison spending increasing by nearly 600 percent (Gotsch, 2019). This growth affects disproportionately minorities - Blacks, Latinos, and Native Americans - and low income communities resulting in disproportionate number of minorities in federal prisons. Federal mandatory sentencing laws also are the impetus for the surge of unnecessarily harsh prison sentences especially for those individuals convicted of non-violent crimes. More than two-thirds of federal prisoners are serving a life sentence for a non-violent crime (Gotsch, 2019). In addition, the US prison system was criticized for its high recidivism rate which sent many repeat offenders back to prison, representing a failure of the prison system to achieve its supposed goals of deterrence and rehabilitation as well as ensure public safety. Finally, public officials were reacting to increased publicity about the inhumane conditions and overcrowding in both federal and state prisons and sought to address these issues through criminal justice reform legislation.

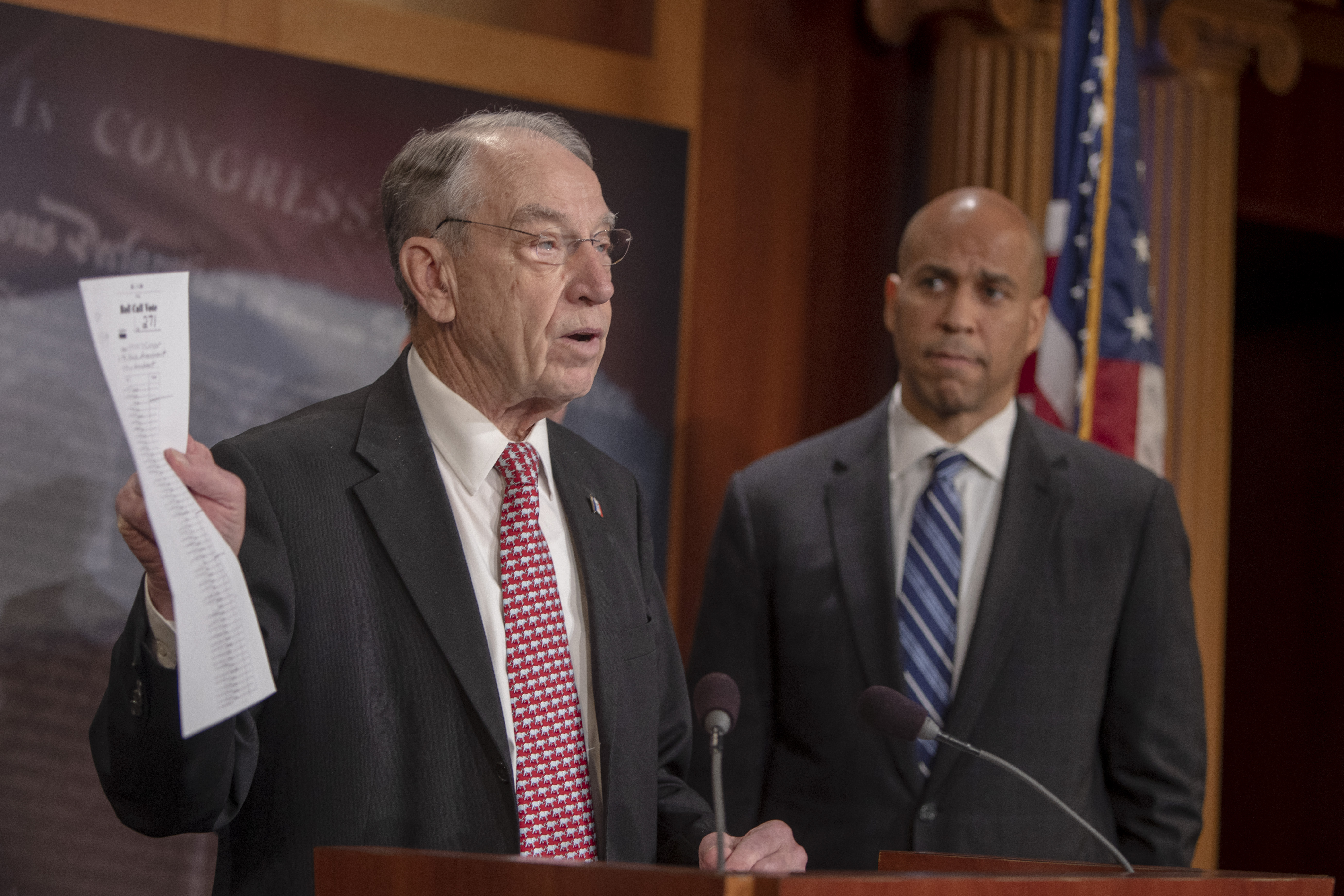

For years Congress had attempted to pass comprehensive criminal justice reform legislation but failed to gain bipartisan support. The only recent attempt at a comprehensive criminal justice reform bill was the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act (SRCA) introduced in 2015 by Senator Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) and Dick Durbin (D-Ill) which failed to pass in 2016. Other previous bills took a more incremental approach to changes in the criminal justice system, focusing more on minor incremental measures on sentencing reform and reducing recidivism rates. Congress tried to address specifically sentencing reform with the Smarter Sentencing Act of 2013 which failed to pass. Two other pieces of legislation which did become law were the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 which addressed inconsistencies in sentences for possession of crack vs powder cocaine and the Second Chance Act of 2007 whose purpose was to reduce recidivism, increase public safety, and assist states and communities to address the growing population of inmates returning to communities though help in four areas: jobs, housing, substance abuse/mental health treatment and families (James, 2019).

The FIRST STEP Act itself also was the product of years of advocacy by people across the political spectrum and was catalyzed eventually by a core group of bipartisan legislators led by Senators Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) (Chair, of the Senate Judiciary Committee), Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) (co-sponsor and a strong criminal justice reform advocate), Cory Booker (D-NJ), and Mike Lee ([R-UT) and Representatives Doug Collin (R-GA) and Hakeem Jefferies (D-NY) in the House. Backed by the White House, the FIRST STEP Act was also supported by an unlikely coalition of conservative and progressive civil rights and criminal justice non-profits including the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Sentencing Project, Brenner Center for Justice, the Koch brothers–backed Right on Crime, American Conservative Union, and over 100 other civil rights organizations, law enforcement groups, prisoners’ and prisoner families right groups such as Families Against Mandatory Minimums. Other key stakeholders involved in the debate over FSA or impacted directly by it include the Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Prisons, law enforcement, prosecutors, judges, prison and sentencing reform organizations, the prisoners and their families. It should be noted that Jared Kushner (President Trump’s son-in-law), whose father was sent to prison for illegal campaign contributions, tax evasion, and witness tampering, was a pivotal influence in getting President Trump’s support for the legislation.

Stakeholders had various motivations for supporting the FSA. Initially introduced to improve conditions in federal prisons and expand recidivism programs for prisoners, FSA aimed to reduce the high rates of recidivism and insufficient opportunities for prisoner rehabilitation and reintegration into society which affects overall public safety (Gill, 2018). Its purpose expanded when lead authors Senator Grassley and Senator Durbin and other key Congressional leaders eventually included provisions to correct flaws in the federal sentencing system which caused racial disparity in sentencing. They also wanted to address the high cost to taxpayers ($80 billion per year) on the federal prison population (Gotsch, 2019). For Congressional leaders, FSA restores fairness and justice to a prison system overwhelmed by mass incarceration and provides a means to reduce prison costs (Grawert & Lau, 2019).

For conservative stakeholders of the FSA, criminal justice reform is based on a moral belief to help offenders to turn their lives around. They also believe it was necessary for public safety. Also, rehabilitation and redemption is a core motivation for conservatives on this issue (Gill, 2018). Further, conservative organizations are disturbed at the high cost to maintain the federal prison population and argue that it is inefficient to continue to spend a large portion of taxpayer dollars on incarcerating a large number of people (Gill, 2018). Finally, conservatives believe that the government should have greater accountability in reducing prison rates.

For liberal stakeholders, criminal justice reform is a question of individual civil rights, fairness in sentencing, and equal protection under the law as federal statutes are applied to minorities, particularly Blacks and Latinos. They believe the criminal system, particularly the application of federal sentences discriminate against minority and low income offenders leading to a disproportionate number of these individuals being arrested and sent to prison. Blacks are more likely to be arrested for the same activities as Whites, and more likely to be prosecuted, convicted and sentenced to longer terms. When the FSA was being debated, their input focused on reforms to sentencing laws - mandatory minimum sentences, drug offender sentences, reductions in excessively harsh or unreasonable sentences which disproportionately affect minorities and low income individuals (Grawert & Lau, 2019).

The FIRST STEP Act (FSA) has been a law for almost 2 years and is in various stages of implementation. To analyze the FSA within the context of the four approaches to public administration and assess the implications of each – traditional managerial approach, new public management approach, political approach, and legal approach - requires reviewing implementation of the FSA based on the different value systems of each approach. Applying the approaches also helps determine whether the FSA is being properly executed and the extent the policy is achieving its objectives through the implementation process and achieving the desired outcomes (Rosenbloom, Kravchuk. & Clerkin, 2009). In evaluating the FSA, different elements of each approach can be observed in its implementation but two approaches, political and legal approach are most prevalent.

Traditional management approach focuses on efficiency and economy in management. The organizational structure, establishing clear goals and objectives with considerable attention given to the problems related to the functioning of an organization like delegation, coordination, and control, and bureaucratic structure exist to maximize effectiveness, efficiency and economy (Fry & Raadschelders, 2014). The values of the traditional management approach to public administration are the least applicable to the implementation of the FSA but still can be observed in three areas: clear policy objectives (reduce the size of the federal prison population, reduce recidivism rates and improve conditions in federal prisons while ensuring public safety); a degree of hierarchical structure in implementation (Congress-DOJ-BOP- individual prisons); the use of comparisons with professional standards to establish benchmarks and well-defined process measures for at least one of its key correctional reform components – the Risks and Assessment Program; and efforts by the DOJ in particular to make implementation cost-effective and efficient. Where it does deviate in the traditional managerial approach is the complexity of the FSA creates more complex administration of its provisions as it involves not only DOJ and BOP which coordinate to implement the correctional reforms but also the federal court system which implements the sentencing reform measures. However, the DOJ has centralized, where it can, many facets of its implementation to provide “efficient and effective implementation” (Barr, 2019).

By Congressional intent, DOJ is the primary department determining how implementation process proceeds and provides oversight for the FSA’s several correctional reforms within the objectives established by Congress. For the sake of efficiency and effectiveness, however, DOJ delegates down to those entities with specialized functions – the BOP and courts. The BOP answers directly to DOJ throughout the process and is accountable to DOJ for BOP decisions and actions and achieving correctional reform objectives (James, 2019). DOJ also continues to provide guidelines on sentencing reforms activities in the federal courts as it seeks to impose a narrow interpretation of sentencing reform provisions of the FSA, particularly those related to prisoners who apply to BOP for lower sentences (Gotsch, 2019).

One of the most important roles DOJ plays is developing and implementing the Risk and Needs Assessment Program, the mainstay of the correctional reforms of the FSA and where rehabilitation and recidivism reduction objectives are established by Congress. The FSA requires DOJ to develop the system to be used by BOP to assess the risk of recidivism of federal prisoners and assign prisoners to evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities to reduce this risk (Skeem & Monahan, 2020). The Risks and Assessment Program eventually implemented, called PATTERN, drew extensively on the professional standards of the rehabilitative services, psychological, and social behavior communities to develop measures throughout the risk and needs assessment process to achieve accurate assessments of prisoners (Skeem & Monahan, 2020).

New Public Management (NPM) promotes a shift from the traditional management approach of bureaucratic administration to business-like professional management. Key themes are decentralization of decision-making, identifying and setting targets and continual monitoring of performance with such tools as audits. It also uses decentralized service delivery using third parties such as non-profits and the private sector (Fry & Raadschelders, 2014). Elements of the NPM approach also are part of the FSA implementation process in two specific areas: decentralizing sentencing reform decision-making - the courts in their judicial role - and the use of third parties to provide public services - non-profits are leading rehabilitative services, job training, and education programs required by the FSA. It is in these two areas, where an important degree of decentralization occurs to allow for greater efficiency although primary control remains with the DOJ. It is also where the NPM concepts of “steering” and “rowing” are evident. NPM prefers “steering” rather than “rowing” as government is best at providing directives and guidance (steering) whereas non-profits are more adept at providing the actual public services (rowing) (Denhardt & Denhardt, 2000). The DOJ is providing directives to both the courts and the non-profits in their work under the FSA provisions but it is these separate entities providing the actual legal and public services.

The courts are responsible for reviewing and ruling on cases of prisoners who are eligible for reduced sentences/no sentences under the sentencing reforms in the FSA. These reforms are related to the retroactivity of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, changes in the mandatory minimum sentences laws for non-violent drug offenders, and expanding the “safety value” which allows judges the discretion to provide less than mandatory sentences for certain drug offenders. Although no target number is established for the courts to release prisoners or not sentence offenders, one of the FSA objectives is for the courts to help reduce the number of prisoners in the prison system in order to reduce mass incarceration (James, 2019).

To implement the FSA’s rehabilitation and re-entry programs, the DOJ and BOP are working with non-profits with the expertise to provide these programs directly to the prisoners rather than provide the service themselves. DOJ is awarding FSA implementation grants to community- and faith-based non-profit organizations specializing in the aforementioned areas. Reauthorization of the Second Chance Act of 2007, a part of the FSA, establishes several grants to non-profits for these purposes including Grants for Family-Based Substance Abuse Treatment, Grant Program to Evaluate and Improve Educational Methods at Prisons, Jails, and Juvenile Facilities, Careers Training Demonstration Grants, and the Community-Based Mentoring and Transitional Service Grants to Nonprofit Organizations Program. The success of non-profits is evaluated based on their performance to reach stated DOJ and BOP targets to reduce the recidivism rates of the newly-released prisoners (James, 2019).

Once passed, implementation of FSA continues to involve examples of collaboration with stakeholders and government agencies, a degree of devolution of authority, and use of implementation networks. As intended by Congress, when developing and evaluating the prisoner Risks and Assessment Program, the DOJ has collaborated with, among others, the BOP, the Office of the US Courts, the National Institute of Corrections, the National Institute of Justice, the FAS Independent Review Committee as well as receiving input from psychological experts and practitioners in the field of recidivism and prisoner rehabilitation, and civil rights and prison reform advocacy organizations (Barr, 2019). To implement the FSA’s rehabilitation and re-entry programs the DOJ and BOP are working with community and faith-based non-profits with the expertise to provide programs focusing on job training, housing, and health directly to the prisoners funding them as well as similar state and local government programs.

Although more a practical necessity than devolution of authority from the DOJ and collaboration, the individual courts are reviewing and ruling on cases of prisoners who are eligible for reduced/no sentences under the sentencing reforms in the FSA. These reforms are related to changes in the minimum sentences laws for non-violent drug offenders, and expanding the “safety value” which allows judges the discretion to provide less than mandatory sentences for certain drug offenders. The work of the courts in this area is essential in addressing the issues of fairness and equity for the minority and low income communities the FSA was intended to assist.

The last approach to analyze FSA against is the legal approach to public administration. The legal approach to public administration embodies four values: Constitutional integrity, procedural due process, individual rights, and equal protection as well as equity and fairness (Rosenbloom, Kravchuk. & Clerkin, 2009). In the legal approach to public administration, public administrators should adopt due process while performing their tasks, protect individual rights, and be fair when resolving conflicts between government and the individual (Christiansen, Goerdel & Nicholson-Crotty, 2011). This approach is less concerned about public administration management efficiency and economy in policies but more about the impact laws and policies have on individual constitutional rights and matters of equity and fairness.

FSA was created in response to flaws in the criminal justice system, particularly sentencing laws created by Congress and administrative policies and practices of the DOJ and BOP and how they are applied to criminal offenders and prisoners. In addition, prisoner treatment, prison conditions while incarcerated, and prisoner rehabilitation are FSA provisions addressing the failings of interactions between BOP officials and prisoners and their families. How these laws are created and implemented involves issues of Constitutional integrity, procedural due process, individual rights, and equal protection, equity and fairness for criminal offenders and prisoners. In the legal approach, the FSA is considered a good policy if it in accordance with these constitutional values.

Under the Constitution and confirmed by the courts (Wolff v. McDonnell, 418 U.S. 539, 555–56 (Supreme Court, 1974)), prisoners still have constitutional rights which must be respected by prison administrators (Legal Information Institute, 2020). The FSA is ensuring the DOJ and BOP are protecting the individual rights of offenders and prisoners while incarcerated by requiring reasonable treatment, decent prison conditions, and improved rehabilitation opportunities required under the Eighth Amendment – preventing cruel and unusual punishments. Further, changes in sentencing laws such as those related to the retroactivity of the Fair Sentencing Act provision (applying drug sentences fairly and equitably) and revisions to severe mandatory minimum sentences are protected rights under the Eighth Amendment - imposing unduly harsh penalties on criminal offenders - and the Fourteenth Amendment – equal protection of the laws and procedural due process. The Eighth Amendment restrains the government"s ability to cause harm to individuals, whether economically through an excessive bail or fine, or physically through incarceration; the Fourteenth Amendment ensures government follows accepted legal procedures before it deprives a person of his life, liberty or property (Legal Information Institute, 2020). The prisoners’ rights under these amendments are being protected with their interactions with officials in the federal court system under FSA.

With respect to implications based on each of the approaches to public administration for FSA, the FSA exhibits primarily the political and legal approaches in its policy-making process and implementation. The FSA was passed in response to serious flaws in the criminal justice system which adversely affected equity and fairness and the constitutional rights of prisoners under sentencing laws, their treatment and conditions while incarcerated, and their ability to be rehabilitated and reenter society. The participation of a coalition of public stakeholders and their collaboration with each other and Congressional leaders demonstrates the representative nature of the FSA policy making process. Finally, implementation networks are prevalent as an essential part of carrying out provisions of the FSA from interagency and private sector collaborations to the involvement of non-profits in providing rehabilitation programs. The FSA also is influenced by the legal approach to public administration through its efforts to ensure the constitutional rights of criminal offenders and prisoners are protected in their interactions with prison officials while incarcerated and the court system when being sentenced. Specifically rights protected under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments dealing with equal protection, procedural due process, and cruel and unusual punishment are addressed in the implementation of the FSA. Based on these two approaches to public administration the FSA could be considered “good” policy. In reality, it’s too soon to tell.

Barr, W. (2019, July). The First Step Act of 2018: Risk and needs assessment system. U.S. Department of Justice Office of the Attorney General. https://nij.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh171/files/media/document/the-first-step-act-of-2018-risk-and-needs-assessment-system_1.pdf.

Gill, M. (2018, December). Threading the needle: The FIRST STEP Act, sentencing reform, and the future of criminal justice reform advocacy. Federal Sentencing Reporter. 31(2). https://doi.org/10.1525/fsr.2018.31.2.107.

Gotsch, K. (2019, December 17). One year after the First Step Act: Mixed outcomes Sentencing Project. https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/one-year-after-the-first-step-act/.

Grawert, A. (2020, June 23). What Is the First Step Act — And what’s happening with it? Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/what-first-step-act-and-whats-happening-it.

Grawert, A. & Lau, T. (2019, January 4). How the First Step Act became law — and what happens next. Brennan Center for Justice. https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/how-first-step-act-became-law-and-what-happens-next.

O’Toole, L. (1997, January-February). Treating networks seriously: Practical and research-based agendas in public administration. Public Administration Review. 57(1). https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/stable/976691?sid=primo&origin= crossref&seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Skeem, J. & Monahan, J. (2020). Lost in translation: “Risks,” “needs,” and “evidence” in implementing the First Step Act . Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 38(3).

United States Sentencing Commission August. (2020) The First Step Act of 2018: First year of implementation. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/research-publications/2020/20200831_First-Step-Report.pdf.

On behalf of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, we write to urge you to vote YES on cloture for S. 756, the FIRST STEP Act, and NO on all amendments. This legislation is a next step towards desperately needed federal criminal justice reform, but for all its benefits, much more needs to be done. The inclusion of concrete sentencing reforms in the new and improved Senate version of the FIRST STEP Act is a modest improvement, but many people will be left in prison to serve long draconian sentences because some provisions of the legislation are not retroactive. The revised FIRST STEP Act, however, is not without problems. The bill continues to exclude individuals from benefiting from some provisions based solely on their prior offenses, namely citizenship and immigration status, as well as certain prior drug convictions and their “risk score” as determined by a discriminatory risk assessment system. While these concerns remain a priority for our organizations and we will advocate for improvements in the future, ultimately the improvements to the federal sentencing scheme will have a net positive impact on the lives of some of the people harmed by our broken justice system and we urge you to vote YES on cloture and vote NO on all amendments to the bill. The ACLU and The Leadership Conference will include your votes on our updated voting scorecards for the 115th Congress.

While the dollar amounts are astounding, the toll that our U.S. criminal justice policies have taken on black and brown communities across the nation goes far beyond the enormous amount of money that is spent. This country’s extraordinary incarceration rates impose much greater costs than simply the fiscal expenditures necessary to incarcerate over 20 percent of the world’s prisoners. The true costs of this country’s addiction to incarceration must be measured in human lives and particularly the generations of young black and Latino men who serve long prison sentences and are lost to their families and communities. The Senate version of the FIRST STEP Act makes some modest improvements to the current federal system.

I. Sentencing Reform Changes to House-passed FIRST STEP Act–Sentencing reform is the key to slowing down the flow of people going into our prisons. This makes sentencing reform pivotal to addressing mass incarceration, prison overcrowding, and the exorbitant costs of incarceration. As a result of our coalition’s advocacy, the new FIRST STEP Act added some important sentencing reform provisions from SRCA, which will aid us in tackling these issues on the federal level.[x] These important changes in federal law will result in fewer people being subjected to harsh mandatory minimums.

Expands the Existing Safety Valve. The revised bill expands eligibility for the existing safety valve under 18 U.S.C 3553(f)[xi] from one to four criminal history points if a person does not have prior 2-point convictions for crimes of violence or drug trafficking offenses and prior 3-point convictions. Under the expanded safety valve, judges will have discretion to make a person eligible for the safety valve in cases where the seriousness of his or her criminal history is over-represented, or it is unlikely he or she would commit other crimes. This crucial expansion of the safety valve will reduce sentences for an estimated 2,100 people per year.[xii]

Retroactive Application of Fair Sentencing Act (FSA). The new version of FIRST STEP Act would retroactively apply the statutory changes of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (FSA), which reduced the disparity in sentence lengths between crack and powder cocaine. This change in the law will allow people who were sentenced under the harsh and discriminatory 100 to 1 crack to powder cocaine ratio to be resentenced under the 2010 law.[xiii] This long overdue improvement would allow over 2,600 people the chance to be resentenced.[xiv]

Reforms the Unfair Two-Strikes and Three-Strikes Laws. The new version of FIRST STEP would reduce the impact of certain mandatory minimums. It would reduce the mandatory life sentence for a third drug felony to a mandatory minimum sentence of 25 years and reduce the 20-year mandatory minimum for a second drug felony to 15 years.

II. Prison Reform Changes to House-passed FIRST STEP Act, H.R. 3356–The revised bill also made some strides in improving some of the problematic prison reform provisions. The new bill strengthened oversight over the new risk assessment system, limited the discretion of the attorney general, and increased funding for prison programming, among other things. The bill now does the following:

Permits Early Community Release and Loosens Restrictions on Home Confinement.The House-passed FIRST STEP Act limited the use of earned credits to time in prerelease custody (halfway house or home confinement). The revised bill would expand the use of earned credits to supervised release in the community. The bill also would permit individuals in home confinement to participate in family-related activities that facilitate the prisoner’s successful reentry.

Reauthorizes Second Chance Act. The revised bill reauthorizes the Second Chance Act, which provides federal funding for drug treatment, vocational training, and other reentry and recidivism programming.

While these revisions to the bill were critical to garnering our support, we must acknowledge that some of the more concerning aspects of the House-passed version of the FIRST STEP Act remain.

III. Outstanding Concerns Regarding the FIRST STEP Act –The bill continues to exclude too many people from earning time credits, including those convicted of immigration-related offenses. It does not retroactively apply its sentencing reform provisions to people convicted of anything other than crack convictions, continues to allow for-profit companies to benefit off of incarceration, fails to address parole for juveniles serving life sentences in federal prison, and expands electronic monitoring.

Fails to Include Retroactivity for Enhanced Mandatory Minimum Sentences for Prior Drug Offenses &. 924(c) “stacking.”The bill does not include retroactivity for its sentencing reforms besides the long-awaited retroactivity for the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010. This minimizes the overall impact substantially. Retroactivity is a vital part of any meaningful sentencing reform. Not only does it ensure that the changes we make to our criminal justice system benefit the people most impacted by it, but it’s also one of the essential policy changes to reduce mass incarceration. The federal prison population has fallen by over 38,000[xvi] since 2013 thanks in large part to retroactive application of sentencing guidelines approved by the U.S. Sentencing Commission.[xvii] More than 3,000 people will be left in prison without retroactive application of the “three strikes” law and the change to the 924 (c) provisions in the FIRST STEP Act.[xviii]

Excludes Too Many Federal Prisoners from New Earned Time Credits. The bill continues to exclude many federal prisoners from earning time credits and excludes many federal prisoners from being able to “cash in” the credits they earn. The long list of exclusions in the bill sweep in, for example, those convicted of certain immigration offenses and drug offenses.[xix] Because immigration and drug offenses account for 53.3 percent of the total federal prison population, many people could be excluded from utilizing the time credits they earned after completing programming.[xx] The continued exclusion of immigrants from the many benefits of the bill simply based on immigration status is deeply troubling. The Senate version of FIRST STEP maintains a categorical exclusion of people convicted of certain immigration offenses from earning time credits under the bill. The new version of the bill also bars individuals from using the time credits they have earned if they have a final order of removal. More than 12,000 people are currently in federal prison for immigration offenses and are disproportionately people of color.[xxi] Thus, a very large number of people in federal prison would not reap the benefits proposed in this bill and a disproportionate number of those excluded would be people of color. Denying early-release credits to certain people also reduces their incentive to complete the rehabilitative programs and contradicts the goal of increasing public safety. Any reforms enacted by Congress should impact a significant number of people in federal prison and reduce racial disparities or they will have little effect on the fiscal and human costs of incarceration.

Allows Private Prison Companies to Profit. The bill also maintains concerning provisions that could privatize government functions and allow the Attorney General excessive discretion. FIRST STEP provides that in order to expand programming, BOP shall enter into partnerships with private organizations and companies under policies developed by the Attorney General, “subject to appropriations.” This could result in the further privatization of what should be public functions and would allow private entities to unduly profit from incarceration.

Fails to Include Parole for Juveniles, Sealing and Expungement. Under SRCA, judges would have discretion to reduce juvenile life without parole sentences after 20 years. It would also permit some juveniles to seal or expunge non-violent convictions from their record. The FIRST STEP Act does not address these important bipartisan provisions.

The ACLU and The Leadership Conference oppose the Cotton-Kennedy amendments to the FIRST STEP Act, and all other amendments. The Cotton-Kennedy amendment #4109 (Div. I, II, and III) serves no other purpose but to undermine the bipartisan support for the revised FIRST STEP Act and ultimately attempts to kill the bill. Division 1 of amendment #4109 to mandate victim notification and publicizing rearrests data sounds innocuous, but is unnecessary under current law, would risk retraumatizing victims, violates privacy standards, and compromises the reentry process. Division 2 of amendment #4109 would burden prison wardens with the responsibility for victim notifications of release and solicit and review victims’ statements prior to a person’s transition to community corrections. Again, this additional responsibility is burdensome for a system already overtaxed and current law permits victims to receive notifications of release if they so choose.

Finally, Division 3 of amendment #4109 creates a new list of unnecessary exclusions to the earned-time credit program – there are already a number of exclusions, and any additions further weaken the bill’s impact. The core of the prison reform bill promoted by conservatives rests on the theory that the new risk and needs assessment system in the bill will effectively determine those individuals who have successfully reduced their recidivism “risk,” are classified as minimum or low risk to public safety, and are thus eligible to use their earned time credits toward early release to community corrections. In our view, if you support the risk and needs assessment system, which is a core piece of the bill, then you should oppose any additional exclusions based solely on the type of offense. A vote in favor of any of these amendments is ultimately a vote against the bill, and we will score your votes in our updated scorecards for the 115th Congress.V. Conclusion

Bringing fairness and dignity to our justice system is one of the most important civil and human rights issues of our time. The revised version of the FIRST STEP Act is a modest, but important move towards achieving some meaningful reform to the criminal legal system. While the bill continues to have its problems, and we will fight to address those in the future, it does include concrete sentencing reforms that would impact people’s lives. For these reasons, the we urge you to vote YES on cloture and vote NO on all amendments to the bill.

Ultimately, the First Step Act is not the end– it is just the next in a series of efforts over the past 10 years to achieve important federal criminal justice reform. Congress must take many more steps to undo the harms of the tough on crime policies of the 80’s and 90’s – to create a system that is just and equitable, significantly reduces the number of people unnecessarily entering the system, eliminates racial disparities, and creates opportunities for second chances.

If you have any additional questions, please feel free to contact Jesselyn McCurdy, Deputy Director, ACLU Washington Legislative Office, at [email protected] or (202) 675-2307 or Sakira Cook, Program Director, Justice Reform, The Leadership Conference, at [email protected] or (202) 263-2894.

[ii] See Roy Walmsley, World Prison Project, World Prison Population List, 12th Edition (June 11, 2018), http://www.prisonstudies.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/wppl_12.pdf.

[v] SeeFederal Bureau of Prisons, Statistics, Population Statistics.Last updated Dec. 13, 2018, https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/population_statistics.jsp.

[vi] SeeFederal Bureau of Prisons, Statistics, Offenses.Last updated Nov. 24, 2018, https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp.

[vii] See Tracy Kyckelhahn, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Justice Expenditure and Employment Extracts, 2012,Preliminary Tbl. 1 (2015), https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=5239 (showing FY 2012 state and federal corrections expenditure was $80,791,046,000).

[xi] A “safety valve” is an exception to mandatory minimum sentencing laws. A safety valve allows a judge to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum term if certain conditions are met. Safety valves can be broad or narrow, applying to many or few crimes (e.g., drug crimes only) or types of offenders (e.g., nonviolent offenders). See 18 U.S.C. 3553(f) (2010)

[xii] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

[xiii] Although the ACLU supported the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, we would ultimate support a change in law that would treat crack and powder cocaine equally; 1 to 1 ratio.

[xiv] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

[xvi] SeeFederal Bureau of Prisons, Statistics, Population Statistics. Last Updated Dec. 13, 2018, https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/population_statistics.jsp.

[xviii] SeeLetter from Glenn Schmitt, Dir. of Res. and Data, U.S. Sentencing Commission, to Janani Shakaran, Pol’y Analyst, Congressional Budget Office, regarding the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2017, United States Sentencing Commission (March 19, 2018), https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/prison-and-sentencing-impact-assessments/March_2018_Impact_Analysis_for_CBO.pdf.

[xx] SeeFederal Bureau of Prisons, Statistics, Offenses.Last updated Nov. 24, 2018, https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp.

[xxi]SeeFederal Bureau of Prisons, Statistics, Offenses. Last Updated Nov. 24, 2018, https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp; E. Ann Carson, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2016 (2018), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p16.pdf.

Near the end of August, a series of pivotal meetings were held at the White House between criminal justice advocates and stakeholders from the administration and the Senate, Trump, and Attorney General Jeff Sessions. That Thursday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) committed to conducting a formal whip count of the prison and sentencing reform package after the midterm elections. Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) called the meetings “a huge step forward in getting a bill passed that will help keep communities safe and make our criminal justice system more fair.”

The sentencing reforms proposed to be added to FIRST STEP are, frankly, quite modest. A compilation of the most minor provisions from SRCA, the provisions would address 924(c) stacking charges, reform 841/851 sentencing enhancements for prior offenses, expand the existing federal safety valve for mandatory minimum sentencing, and apply the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 retroactively.

Addressing stacking charges under 18 U.S.C. 924(c) is the least controversial of the proposed changes, simply ensuring that it is applied only to true recidivists. This would prevent first-time, nonviolent offenders such as Weldon Angelos from being unjustly sentenced to 55 years in prison for, in Weldon’s case, three separate sales of small quantities of marijuana.

Similarly met with limited controversy is a tailored fix to the sentencing enhancements under 21 U.S.C. 841 and 851. Currently applicable to all former felony drug offenders, the fix would modify and focus sentencing enhancements to serious drug felons and expand them to serious violent felons. This narrow fix will enhance public safety as dangerous individuals are no longer left on the streets while individuals who are significantly lower safety threats are incarcerated.

Expanding the existing federal safety valve is commonsense policy. The proposed expansion would open up the option of a safety valve to those qualifying individuals with up to four criminal history points instead of only one, excluding anybody with a single three-point offense. Conservative states like Georgia and Mississippi have implemented safety valves.

The simple fact is that we appoint judges to exercise their legal expertise and issue sentences that fit the crime a defendant is found guilty of. Modest expansions of the safety valve allow judges to practice their expertise in applying the law to serve justice in the most fair way.

Finally, retroactively applying the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 would allow individuals sentenced under the reactionarily-enacted 100-to-1 crack cocaine versus powder cocaine disparity to appeal their cases for a reduced sentence under the compromised 18-to-1 disparity passed with unanimous support in 2010.

As the U.S. Sentencing Commission determined, those who received retroactively reduced sentences under the 2010 law have an identical rate of recidivism to those who did not. This modification gives justice to those suffering from exceedingly long sentences and saves taxpayer dollars with no negative effect on public safety.

The goal of justice reform is to enhance public safety in commonsense ways that save taxpayer dollars and improve communities by ensuring those who return to them after incarceration are fully rehabilitated. The work that reform senators and others have done to advance these policies is commendable.

The House has spoken its support for the FIRST STEP Act, as have stakeholders across the political spectrum. With a deal on the table that strikes such a precise balance and a positive message from Leader McConnell to move the package, conservatives now have their turn to act on good policy.

The First Step Act was inspired by reforms in states like Texas, which, since its 2007 shift away from building more prisons and toward community-based supervision and treatment, has cut crime 40 percent while reducing incarceration by 34 percent. As the “first step” moniker implies, there is still unfinished business at the federal level.

We can start by making retroactive the drug sentencing reform provisions in the First Step Act. Doing so could benefit 4,000 people. These provisions were hardly radical. One reduced mandatory life without parole for a third felony drug offense to 25 years and dropped the 20-year mandatory minimum for a second felony drug offense to 15 years. The First Step Act also expanded the safety valve that allows a court to impose a prison sentence slightly below the mandatory minimum in cases involving low-level drug offenses by those with little criminal history, but this was also only prospective.

The case for retroactivity is even stronger following a U.S. Sentencing Commission study in July demonstrating that reducing time served for drug offenses does not increase recidivism.

Action should also be taken to streamline federal probation. The average federal probation term is 41 months, but a two-year term is slightly more effective than a three-year term for reducing recidivism.

Since 2007, many states have adopted earned-time policies that provide an incentive for exemplary conduct while on community supervision. Results from Missouri show this lowered caseloads while preserving public safety. Additionally, 7 in 10 revocations from federal probation occur due to technical violations, such as missed meetings or positive drug tests. States, including South Carolina, have seen positive results from recent policies to reduce such revocations through graduated sanctions. A survey of federal judges found they want more discretion to use alternatives to revocation in responding to positive drug tests, suggesting a need for Congress to act.

Action is also needed on record sealing and certificates of rehabilitation. The bipartisan Clean Slate Act would seal the records of a low-level federal drug possession offense after two years if the person has not reoffended. This legislation would help someone found with a joint in an airport or national park when they seek employment and housing.

Such initiatives often involve partnerships between law enforcement and credible messengers. These include people who were formerly incarcerated, often gang members, before turning their lives around, positioning them to help others avoid the same mistakes. After implementing such a model in 2012, known as Ceasefire, Oakland, Calif., cut its shootings in half by 2018.

These programs wisely target resources and interventions to the very small percentage of the population statistically most likely to shoot someone or be shot, and provide these individuals with positive pathways, such as connections to employment and mentoring. At the same time, they build trust between communities and law enforcement, and unequivocally communicate that acts of violence will be prosecuted.

Criminal justice policy deeply impacts lives and liberties. It is too important to be the province of any one political party or candidate. Regardless of what this election holds, we all benefit if our leaders take the next steps toward a federal system that balances the need for incarceration in some cases with the goals of promoting second chances and preventing crime.

After many months of negotiations between a Republican-controlled U.S. Congress and the Trump Administration, on December 21, 2018, the First Step Act of 2018 (FSA) was signed into law by President Trump.[1] While this legislation was named the “First Step Act” to signal that it was the first attempt at incremental change to the federal criminal justice system, that name is actually a misnomer and ignores several successful reforms that preceded the legislation’s passage.[2] The FSA was actually the next step of many previous steps that have resulted in reforms far more significant to the federal criminal justice system.

Well before Jared Kushner, President Trump’s son-in-law, joined with some conservative and progressive organizations and became interested in federal criminal justice reform, there were many criminal justice, civil rights, human rights, and faith-based activists who successfully advocated for justice reform, including sentencing reform, on the federal level over the past fifteen years. Early supporters of the FSA did not think that President Trump or the Republican Congress would support changes to sentencing laws, and were satisfied with including what they considered prison reform provisions or “back end” changes to the criminal justice system.[7] In addition, former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, the DOJ, and several members of Congress opposed including sentencing reforms.[8]

During the first six months after the law was enacted, almost all of the people who have benefited from the law benefited from the sentencing provisions that early supporters and former Attorney General Sessions were willing to sacrifice. However, many criminal justice, civil rights, and faith advocates, as well as members of Congress understood that no true changes to the federal system could happen without addressing the unjust sentencing laws that have contributed to the mass incarceration crisis in this country.[9]

The possibility of these efforts actually began under another Republican President, George W. Bush, who in his 2004 State of the Union speech said, “America is the land of second chance, and when the gates of the prison open, the path ahead should lead to a better life.”[11] This sentiment being expressed by a Republican President, a member of a party that has been known as the more “law and order” political party of the two major parties, created an opening to begin a conversation about criminal justice reform. Later that year, President Bush announced his Prisoner Re-Entry Initiative (PRI) designed to assist formerly incarcerated people in their efforts to return to their communities. PRI connected people returning from prison with faith-based and community organizations to assist them in finding work and prevent them from recidivating.[12] Ultimately, Congress passed legislation in 2008 called the Second Chance Act (SCA) that created funding for organizations around the country to help people coming home from prison by providing reentry services needed to transition back to their communities.[13] The concept for this federal funding was born out of President Bush’s PRI.

In 2005, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Brennan Center for Justice, and Break the Chains organizations published a groundbreaking report titled, Caught in the Net: The Impact of Drug Policies on Women and Families.[14] This report was one of the first publications to document the alarming rise of incarceration of women for drug offenses. In 2005, there were more than eight times as many women incarcerated in state and federal prisons and local jails as in 1980. The number of women imprisoned for drug-related crimes in state facilities increased by 888% between 1986 and 1999.[15] These numbers are important because more than forty-five percent of the people in federal prison are there for drug offenses, of which seven percent are women.

Almost simultaneously, federal advocates began to reinvigorate efforts to address one of the most notoriously discriminatory federal criminal laws, also known as the 100 to one crack to powder disparity. This law, enacted in 1986, punished people more harshly for selling crack cocaine than it did powder cocaine. Under the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, a person would receive at least a five-year mandatory minimum sentence for selling 500 grams of powder cocaine but would receive the same sentence for selling merely five grams of crack cocaine. More importantly, what was apparent at the time was that crack cocaine was used in African-American communities because it was more readily available due to the lower cost compared to powder cocaine. Powder cocaine was used more often by whites because they could afford to purchase the more expensive drug. In 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA 2010) which reduced the 100 to one disparity between crack and powder cocaine to eighteen to one and eliminated the five-year mandatory sentence for possession of crack cocaine.[16]

Between 2005 and 2019, a combination of legal, legislative, executive, and U.S. Sentencing Commission (Sentencing Commission) law and policy changes resulted in reforms that led to a decline in the federal prison population of more than 38,000 people.[21] At its height, the BOP held more than 219,000 people in federal prisons across the country. As of September 2019, those numbers have decreased to 177,251.[22] The reason for the significant decline is because these legal and policy changes were focused on revamping federal sentencing and retroactive application of changes. Similarly, the most impactful provision of the FSA has been retroactivity of the FSA 2010. The Sentencing Commission estimates that the expansion of the 1994 safety valve provision[23] will also have a significant effect for years to come.

Some of these reforms took place years before the “First Step” Act or bills that preceded it[24] were even thought of, but it is important to understand how these and other policy changes laid the foundation for a “First Step” Act to become law. Furthermore, early supporters of the “First Step” Act cannot rewrite history with the title of a bill. In the end, this legislation was an example of incremental change to the federal criminal justice system, but it was not the first example, nor the most significant. In order for history to reflect an accurate picture of how reforms to the federal criminal justice system have successfully unfolded over the past decade or more, this Article will detail the actual first steps that led to a political environment in Washington where criminal justice reform could be considered, and ultimately enacted in 2018.

Mandatory minimum penalties are criminal penalties requiring, upon conviction of a crime, the imposition of a specified minimum term of imprisonment.[25] The Boggs Act, which provided mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses, was passed in 1951.[26] In 1951, Congress began to enact additional mandatory minimum penalties for more federal crimes.[27] Congress passed the Narcotics Control Act in 1956, which increased these mandatory minimum sentences to five years for a first offense and ten years for each subsequent drug offense.[28]

Since then, mandatory minimum sentences have proliferated in every state and federal criminal code. In 1969, Nixon called for drastic changes to federal drug control laws. In 1970, Congress responded with the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, supported by both Republicans and Democrats, which eliminated all mandatory minimum drug sentences except for individuals who participated in large-scale ongoing drug operations. Nixon signed the Act on October 27, 1970.[29]

Ironically, the next year, Nixon declared a “war on drugs” and increased the presence of federal agencies charged with drug enforcement and supported bills with mandatory sentences.[30] John Ehrlichman, an aide to Nixon, more recently has admitted that the “war on drugs” was actually a war on black people:

Mandatory minimum sentences for federal drug offenses emerged again after the death of Len Bias. In 1986, University of Maryland basketball star Len Bias died of a drug overdose just days after the Boston Celtics picked

8613371530291

8613371530291