first step act 2018 safety valve pricelist

The Act requires the submission of several reports to review the BOP"s implementation of the law and assess the effects of the new risk and needs assessment system.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

As President Donald Trump signed the First Step Act1 into law on December 21, 2018,2 a group of my friends, all veteran criminal justice advocates, threw out alternative names for the legislation: the “Last Step Act,” the “Baby Step Act,” the “Stutter Step Act.” The dark mood even at a time of victory reflected a learned reality: criminal justice reform, even when desperately needed, moves at the pace of a line at the DMV.

It would seem that criminal law reform should be racing along at a breakneck pace, given these unusual alliances and the opportunities given the new Biden administration. News flash: it is not, either at the federal or state level.9 Here, I will try to describe the reasons for that languid pace and assess the impact of what President Lincoln called (in referring to military progress) “the slows.”10

Part I below will describe this lethargic pace of reform. It lies in stark contrast with the flashy dynamic that created the need for such reform: those swift surges in retributive impulses in which tough-on-crime measures pile one on top of the other. The harsh treatment for crack cocaine offenses, which ramped up quickly in the mid-1980s and has been very slowly undone for 30-some years, is the model for this tragic pattern. The attention to crack, however, masks a broad movement across criminal law in the same direction, spanning federal and state systems, and reflecting similar results. In addition to crack, I will take a look here at the bizarre and seemingly intractable placement of marijuana in Schedule I of the federal code and then turn to state examples of legislative lethargy in the face of clear injustice.

Finally, Part III will suggest a path to accelerate the process, by addressing each problem in turn. First, reformers must find a way to coordinate efforts rather than competing for resources and attention. I suggest the funding and formation of a meta-organization that can at least provide some focus and coordination to the dozens of disconnected advocacy groups searching for relevance. Politics is difficult, of course, but there are signs of hope emerging even now. Still, there needs to be a higher and more consistent profile for criminal justice reform, so that the rewards of supporting reform at least equal the political benefits of being “tough on crime.” At the same time, racial appeals need to be called out as such, and there must be an affirmative restructure of the policy apparatus to dilute the unique power of prosecutors to reify the status quo. Perhaps most importantly, reform proposals need to be marked by boldness, particularly in those narrow windows of time when change is most possible.

Despite consistent and principled criticism from across the political spectrum, incarceration rates in the United States have not responded in kind. Between 2007 and 2017, imprisonment went down, but only by 10%.12 (We are still sorting out the effects of the COVID pandemic on incarceration). Of that decline, only a fraction can be attributed to state or national policy and legislative changes at the state and federal level, since some of the decline is likely to have been caused by more reasonable charging and sentencing practices by local prosecutors and judges as they adjust to these same influences.

The 1986 crack law was just one of several developments building on one another in the 1980s to lay the groundwork for retributivism and over- incarceration in the federal system.15 It is, in retrospect, shocking to see the brief period in which so much harm was done. In 1984 alone, Congress managed to create a sentencing commission to formulate mandatory guidelines, 16 re-instate the federal death penalty, 17 eliminate parole prospectively,18 and amend the bail laws by creating broad presumptions of detention in drug trafficking and other cases.19 Then, 1986 brought the mandatory minimums of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act,20 and 1987 saw the arrival of the new, and remarkably harsh, mandatory sentencing guidelines.21 Finally, Congress piled on even more, passing the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988, which (among other provisions) applied the mandatory minimums in drug cases to co-conspirators.22

By that point, in 1995, everyone knew or should have known how wrong crack sentences were. In preparation for its own vote on equalizing crack and powder ratios, the Sentencing Commission produced a staff report examining the assumptions that underlay the original legislation. Among other things, the report set out a central dysfunction that powered the whole mess, concluding that “[d]espite the unprecedented level of public attention focused on crack cocaine, a substantial gap continues to exist between the anecdotal experiences that often prompt a call for action and the empirical knowledge on which to base sound policy.”36 In other words, the legislation was based on stories, not data. The report also exploded the myth of racial neutrality, revealing that Blacks and Hispanics accounted for 95.4% of crack convictions, while over half of crack users were white.37

The Sentencing Commission, even after the failure of its equalization proposal in 1995, stayed on task in seeking a change that Congress would accept. In 1997, they tried again with the same conclusion, reiterating the 1995 report with a more modest reform proposal.39 In 2002, the Commission released another report on crack sentencing, with both more pointed factual conclusions and more modest policy proposals.40 This time, the Commission specifically found that the then-current penalties exaggerated the relative harmfulness of crack,41 that those penalties were too broad and usually were applied to lower-level offenders,42 that they were disproportional to those applied to other offenses,43 and that the ratio’s severity “mostly impacts minorities.”44 The 2002 report acknowledged that the data was in—and that the facts did not support the 100-to-1 ratio.45

Still, nothing happened. We knew for certain that the 100-to-1 ratio was racist. We knew it rested on disproven “facts,” such as the myth of crack- fueled “child predators.”46 We knew it did not meet the mandate of proportionality. And yet, nothing happened.

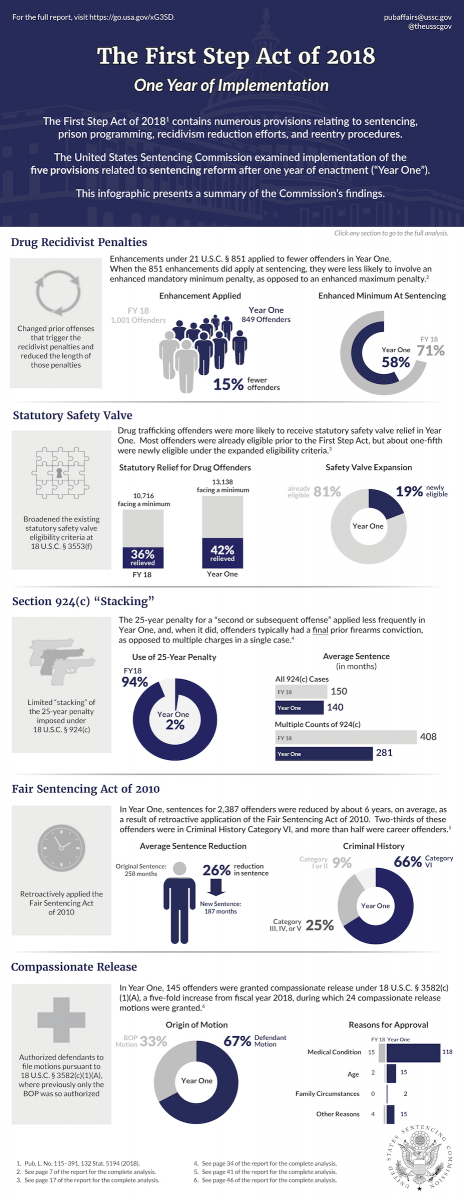

That crack widened in 2010, when Congress passed (and President Obama eagerly signed) the Fair Sentencing Act, which altered the weight thresholds for mandatory minimums applying to crack and powder to 18- to-1.49 This was a big change, but the good news was mitigated by two strange facts. First, instead of equalizing crack and powder sentences, an unusual new ratio was employed. The odd ratio of 18-to-1 was reportedly a compromise worked out between Senators Dick Durban and Jeff Sessions.50 The second unfortunate anomaly was that the reform was not made retroactive51—that is, it did not apply to those already sentenced, meaning that those already in prison would continue to suffer under a measure that had been rejected as too harsh.

The second anomaly—the failure to make this important change retroactive to those already sentenced—was not fixed until President Donald Trump signed the First Step Act in December of 2018.52 Thus, it took over eight years, six years of the Obama administration and two under Trump, to make this right. The other anomaly, the failure to equalize the sentencing of crack and powder cocaine, remains in both the statute and the sentencing guidelines as of July, 2021.

In 1970, Congress tried to create order in narcotics control by organizing problematic53 drugs into five progressively less harmful “schedules” that were defined by three key metrics:54 whether or not the substance has an accepted medical use, potential for abuse, and safety of use under medical supervision if there is an accepted medical use.55 Thus, drugs with a supposed “high potential for abuse,”56 with “no currently accepted medical use”57 and “a lack of accepted safety for use . . . under medical supervision”58 are categorized in Schedule I.59 Conversely, Schedule V includes drugs that have a “low potential for abuse,” relative to those in other schedules,60 a “currently accepted medical use,”61 and “limited physical dependence or psychological dependence” relative to other drugs.

While the federal government sat on its hands, state governments began to act on their own. Leading the way, in 1996 California legalized marijuana for medical purposes through a ballot initiative and was soon followed by five other states (Alaska, Arizona, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington) in 1998.74 The way in which the people spoke in those states—declaring explicitly that marijuana did have medical uses—drove a stake through the heart of the stated rationale for placing marijuana in Schedule I. In the ensuing years, of course, the acceptance of medical marijuana reached the overwhelming majority of Americans. As of 2019, only four states (Idaho, Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota) barred all forms of marijuana and its active ingredient under state law,75 while eleven states and the District of Columbia had legalized marijuana for non-medical recreational use.76

The failure of the Obama administration to make this obvious move is especially perplexing. Keeping marijuana on the top schedule had broad impacts, not the least of which was that it hindered research into the effectiveness of the medical marijuana that was flowing through the state systems.78 Even with a President and Attorney General who held themselves out as progressives and had the power to change the scheduling without the involvement of Congress, nothing happened—the Controlled Substance Act and its nonsensical categorization of marijuana remained in place eight

Even as the federal system struggled to right the most basic wrongs, similar movements were proceeding in the states. While some of the state reforms have been significant, they are limited in significant ways that reflect the difficulty of reversing the harsh-on-crime policy ratchet. In the end, state-wide measures may prove to be less significant than the national movement to elect progressive District and County Attorneys,82 a project that wisely does an end-run around the lethargy of legislatures in enacting reform by going straight to the broad discretion in the hands of prosecutors. The quick and significant success of this initiative is to be applauded, but it also establishes a stark contrast with the slow pace of policy change at the state and national level. It is fair to say that these local actions are at least in part a product of our broader failures and the frustration this produces.

California has been a relative success story, as a series of reform measures (combined with other factors) has reduced incarceration from about 171,000 in 200683 to around 115,000 people locked up at the start of 2019.84 The changes in California were propelled by a number of forces, with finances being a primary incentive. At its peak in 2006, a system designed to house about 85,000 people was stuffed with about double that number,85 meaning that the state had to either spend a lot of money building prisons or reduce the prison population. When he took office in 2004, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger immediately faced a crisis, forcing him to release prisoners even as he opened a new prison.86

A second driving force came later in that decade, in the form of a federal mandate. In 2009, a three-judge panel, later affirmed by the Supreme Court,87 decried California’s prison overcrowding and required a reduction of at least 40,000 prisoners.88 California had no choice but to act.

Beyond Schwarzenegger’s reflexive reactions, a series of reforms have made a lasting difference. These have included a 2011 law that shifted many inmates from state prisons to county jails89 (thus putting a financial burden on the political unit—the county—that makes charging decisions)90 and the implementation of Proposition 47 in 2014, which reduced some property and drug crimes from felonies to misdemeanors.91

Unfortunately, though, a familiar political dynamic kicked in. Two law enforcement groups, the Florida Sheriffs Association and the Florida Prosecuting Attorneys Association, pushed back.102 Their claim was that the changes would be unfair to victims and that the reforms would increase crime at a time when crime was declining. As the Sheriffs Association put it, “Allowing criminals to serve only a fraction of their sentence sends the clear message that criminals are more important than victims and that victims’ rights do not matter. A major reason we enjoy a low crime rate today is because criminals are serving the time deserved and not getting a ‘get out of jail free’ card.”103

Even with those relatively small numbers, a concern for costs and fairness drove bipartisan support for Senate Bill 91 (SB 91), which was signed into law in July of 2016.111 Like other proposed reforms, SB 91 was styled as a “justice reinvestment act,” which intended to use data to target lesser imprisonment for some offenders and then use the savings from averted prison costs to reduce recidivism.112 The resulting legislation relied on studies from groups including the Pew Research Center and created four broad changes in Alaska’s criminal practice: (1) pretrial practices were changed to incorporate data-driven outcomes; (2) sentencing practices were altered to focus long sentences away from low-level nonviolent offenders; (3) re-entry, parole, and probation practices were reformed to enhance the chances of success for returning citizens; and (4) oversight and accountability features were added to the system as a whole.113

In 2018, Mike Dunleavy ran for governor and promised a full repeal of SB 91’s reforms.121 On July 8, 2019, the newly-elected Governor Dunleavy first announced a “war on criminals”122 and then made good on his promise to get rid of the reforms, signing the repeal of SB 91123 in a ceremony held in an airplane hangar.124 At the time of the repeal, no plan was in place to account for the costs of imprisoning more people due to the repeal. Despite showing signs of success, criminal law reform in Alaska was gone almost before it arrived.

There certainly is no single cause of our languid reforms, and no proven way to measure and quantify those causes. Some inputs, though, are likely involved, and I discuss three of them here. First, the nature of the contemporary two-party political system in the United States probably has something to do with it. Too often, politicians are rewarded for playing to fear, and there is no easier go-to for fearmongering than crime. Within that context, race cannot be ignored as a historical and continuing tool of fear- mongers. The stay-the-course influence of prosecutors also plays a primary role in both state and federal political systems, working to stymie reforms that would take away their power. Second, even as the group of advocates for criminal justice has grown, they have become fractured and atomized, limiting their effectiveness. Finally, there is a certain allure to an incrementalism that allows us to claim victories despite the slow pace of change. Some might argue that it is the most likely path to success in the end, and that incremental changes necessarily take time to implement and even more time before the benefits are realized. However, incrementalism masks its price and exaggerates success by frequently creating cause for celebration, and the banquets and awards obscure the darker reality of a largely unchanged system.

In the United States, policy is filtered through politics, and that aspect of democracy has proven to be a brake on reform. It is not the basic mechanizations of democracy that are at fault, of course—the ability of people to choose their representatives can serve to create or solve problems equally—but a distorted dialogue that is fueled by fear and at times has been employed by members of both parties. A corporate mainstream news media, click-bait social media, and fearmongering politicians have turned the mechanics of democracy against the better angels of our policy debates, all of which is exacerbated by the absence from the debate of those most impacted by these policy decisions: people in prison.

“You know, Mark,” one skeptic of my work once told me, “the crack- dealer demographic is a very small voting bloc.” It was a bad joke, but it hits at a core truth: those most directly affected by over-incarceration are the people in our society least able to affect policy through democratic means because those in prison are almost always denied the ability to vote.125 In fact, there is no other policy area where American citizens targeted by a government policy are so directly prohibited from addressing that policy through the ballot box. This makes criminal justice unique.126 In the debate over social security, for example, activists can marshal the voting power of millions of social security recipients.127 No such ability exists for those who argue against over-sentencing.128

Two fundamental and immutable truths drive media coverage—both in the mainstream and in social media—towards exaggerating the effects of crime. First, news media covers what does happen (that is, crime occurring) rather than what does not happen (crime not occurring). Second, all media sources are fundamentally outlets for storytelling, and that favors anecdotes over data.

On the first dynamic, it is simply within the nature of the press that they will report on events rather than non-events. ‘Crack epidemic strikes’ or ‘opioid crisis consumes community’ is a headline, while ‘no drug crisis, really,’ will not be as interesting. A good example of this involves methamphetamine. For years, informal meth labs plagued much of America, and the problem was widely reported, often with a focus on the very real dangers of the labs themselves.129 The labs were full of toxic chemicals, which endangered current and future occupants.130 The labs often exploded.131 And the human cost of obtaining materials (often by theft) and running the labs—even apart from the meth use itself—was a big problem, particularly in rural areas. One report from 2002 described a teenage boy who burned down his grandmother’s house, two men who climbed over a razor-wire fence into a rail yard to steal a tanker car of ammonia gas, and a father who walked away from his small children, leaving them crawling around in a house full of acidic chemicals strong enough to burn through the floor joists.132

Surprisingly, the impact of media stories and images can be even more important in forming negative impressions than actual lived experiences. As Rachel Barkow has pointed out, there is no statistically significant relationship between punitive beliefs and having been a victim of crime, but there is a significant relationship between those beliefs and watching a lot of crime stories on television.141 In other words, real-life experiences do not strongly affect the way we feel about criminal justice, but the media’s interpretation of what is going on—often in communities other than our own—does affect our policy outlooks.

One example of this dynamic was a primary driver of the excessive crack sentences that federal law demanded for far too long. Like any story of narcotics use, crack was used by addicts and non-addicts alike, and not everyone who used crack ended up a tragedy.142 Moreover, as even the United States Sentencing Commission came to realize, crack’s active ingredient was simply powder cocaine.143 Yet, media depictions of crack used charged language and racially-loaded images to describe crack dealers: “thugs,”144 “crack whores,”145 and “super-predators.”146 The result was predictable: people concluded that the evil of crack supported the most draconian of sentences, slowing rational reform.

Certainly, Trump did not create the tactic of fear-mongering over crime (though his ability to do so at a time of record-low crime is relatively unique). President George H.W. Bush was particularly fond of this technique, as demonstrated by a bizarre display in 1989. Planning for a televised speech, Bush had federal agents manufacture a crack sale across the street from the White House, and then waved the resulting baggie of crack at the cameras as he warned of the dire portents of the crack “epidemic.”149

What we do know is that black Americans are no more likely to use or sell illegal drugs than whites155 but are disproportionately arrested and convicted for narcotics crimes.156 Beyond the simple moral wrong in that kind of differential racial outcome, the fact that drug defendants are so often black also allows racial appeals to work—that is, the prevalence of blacks among the selected group of named and shamed “criminals” reifies the skewed racial views of whites, who conclude incorrectly that black people are more prone to crime.

Moreover, when white citizens are led to perceive that drug crimes are largely committed by non-whites, they likely conclude that the human costs (imprisonment and other punishments) of the War on Drugs will be borne by people unlike them, and that this is rational. To put it more bluntly, the idea that narcotics are a “black” problem inures other citizens to the broader interests of justice and the need for reform, since the pain exacted by the current system will be extracted from an “other.”

A few years ago, Rachel Barkow and I raised a hypothetical: imagine that a newly-elected president makes a stunning announcement on the first day of her term—that she is turning criminal law matters over to the Federal Defenders’ Office based on the extensive knowledge that the Defenders have in the field.157 Her primary advisor on criminal justice issues would be the Chief Defender in Washington D.C., and experts from the Defenders’ offices would speak for the administration before the Sentencing Commission and Congress. Pending legislation or guideline amendments would be supported only if the Defenders were on board, and they would also be put in charge of federal prisons, forensic labs, and the clemency process.158

On the White House website, the Obama administration laid out a compelling case for reform, asserting that “meaningful sentencing reform, steps to reduce repeat offenders, and support for law enforcement are crucial to improving public safety, reducing runaway incarceration costs, and making our criminal justice system more fair.”161 Obama’s commitment seemed to be more than symbolic. When he visited those incarcerated in an Oklahoma federal prison, he seemed genuinely chastened by what he saw and reflected “there but for the grace of God.”162 He took a group of clemency recipients to lunch at Busboys and Poets,163 a Washington D.C. restaurant, which presents itself as a hub for social change.164 He even crafted a pro-reform law review article for the Harvard Law Review at the end of his second term.165

Though Attorneys General can have some sway on reform issues, states lack a centralized prosecution hub like the Department of Justice; instead, prosecution is taken up in most states by District or County Attorneys who run for office.169 These local prosecutors, though, often oppose reform both when they run for office and when they interact with the legislature.170

Notably, this critique of state prosecutors as a force against reform must account for the growing number of elected prosecutors who came to office expressly as reformers.173 It is no longer fair to assume that an elected prosecutor is an opponent of reform. The progressive prosecutor movement is new enough that it is too early to measure its effect beyond new policies within each new prosecutor’s own jurisdiction (though certainly those internal reforms are important), but over time the impact may be significant.

In other realms of advocacy, people know who the leaders are. In support of gun rights, it is (for now)176 the National Rifle Association (NRA).177 In the field of protection of older Americans, it is the American Association of Retired Persons (now known just as AARP).178 Trade groups have combined lobbying groups like the Auto Alliance.179 Even within the realm of criminal law (as already discussed here) the DOJ acts as an advocate.180 The benefits of clear leadership in a field of advocacy are plain: such behemoths can leverage a wealth of experience, established relationships, and money to either pursue or retard change.

Within the area of criminal justice reform, there is no such behemoth. Instead, there is a broad diversity of non-profits, which compete for talent, financial support, pro bono help from law firms, and access to power.181 As a result, it is rare that advocates are well-aligned in their goals and methods, and there is significant overlap of effort by unaffiliated groups. In the face of effective, unified opposition by prosecutors, it should not be surprising that reform groups struggle to get traction.

A continuing challenge for this loose but large band of advocates is to remain sensitive to the voices and interests of crime victims and the interests of crime control. This is not because crime victims are necessarily the enemies of reform—in fact, a significant number of crime victims support reforms, even those that would shorten sentences,200 and some crime victims have taken a leadership role in reform efforts.201

The larger challenge is that unless crime control and victims are taken seriously, allegations that reformers value incarcerated people over crime victims and public safety will hit home. Certainly, many groups have been conscientious about emphasizing the legitimate ability to reduce incarceration and crime at the same time.202

Advocates for reform face a conundrum. They can seek broad systemic changes, which are a low-percentage shot but pay off big if they succeed, or they can focus their efforts on smaller, incremental changes that offer a better chance for victories along the way. A problem with incrementalism, of course, is that inevitably some injustices remain on the table for years or decades even as things get nominally better. For example, consider the incremental approach to the reform of crack laws:203 first came court rulings that allowed for some discretion by judges to ignore the harsh guidelines.204 Next came the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced the disparity in sentencing between crack and powder cocaine but did not eliminate it or make the changes in the law retroactive.205 Then, nearly ten years later, the First Step Act finally made those changes retroactive, but did not close the disparity.206 The cost of this incremental approach to fixing an obvious problem was years of unnecessary incarceration for thousands of people. But, of course, it also allowed for the release of thousands of people from prison,207 each with their own story of redemption.208 As Families Against Mandatory Minimums founder Julie Stewart put it in describing her group’s support of the Fair Sentencing Act, “Since 1995, when Congress killed the reform of the crack sentencing guidelines, nearly 75,000 people have received federal crack cocaine sentences. We will not allow another 75,000 to be sentenced at the current unjustifiable levels . . . I won’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”209

There is another factor that promotes a limited ambition when it comes to the reduction of America’s prison population: the distinction between violent and non-violent offenders.212 It is much more politically palatable to seek reduced sentences for non-violent offenders,213 but to achieve ambitious goals such as cutting the prison population in half we would have to reach into the pool of those convicted of violent offenses to realize success.214

Because of the nature of federal jurisdiction, relatively few federal prisoners are there for violent offenses.215 The federal system, though, is only a small (but significant) fraction of the incarceration system in the United States.216 In the state systems, where most of the action is, 55% of those locked up are there on charges of violent crime.217 That means that if we are to reach the commonly-proposed goal of cutting incarceration by 50%,218 we are going to have to consider cutting sentences for those who have committed violent crimes. That does not seem to be something that even progressive Democrats have much of a taste for right now,219 and even the editorial board of the relatively liberal Washington Post opposed a D.C. proposal to lower sentences for some young violent offenders.220

If over-sentencing in the United States is wrong (and it is), then there is an imperative to fix that grave mistake immediately. The cost of not doing so is nothing less than life and freedom, two of the things that Americans hold most dear. Incremental successes do impact lives, but they also leave behind too many for it to be a principled process.

First, we must do a better job as advocates. We should sometimes be willing to be followers and seek out a unifying message. This will require a new role for one or more of the big funders in the area: turning away from creating dozens of new organizations, and turning towards coordinating and growing the ones that we have. In so doing, we need to strengthen our message by including plans to keep crime low and respect the victims of crime.

One way to move towards this goal would involve creating a meta- organization that could direct resources, talent, and connections to existing organizations and help to coordinate their activities. It is unrealistic (and possibly wrongheaded) to think that such a meta-organization would or should control or usurp the independence of existing groups, but a step towards some kind of coordination would be welcome.

Fortunately, two men have the ability to do this: Charles Koch223 and George Soros. Despite very different political philosophies, Koch224 and Soros225 have both been very active in funding and promoting criminal justice reform, and have had some funding or training role in the establishment and success of many of the advocacy groups in the field.226

The pitch to Koch and Soros is simple: Fund a standing organization to lead this fight. Then funnel money to individual groups through that standing organization and begin to coordinate goals and activities. It will free those groups from constant fund-raising and competition with one another and allow for efficiency and effectiveness at a national level.228 Over time, too, specialization will evolve among the groups both in the goals they address and the constituents they serve. The governing board of the meta- organization can have representatives from these constituent organizations, and the larger body can create active roles for academics and individuals who are deeply invested in this fight including (importantly) those who have been incarcerated themselves.

To accelerate reform, it will be necessary to take the costs of crime seriously. The political pushback against reform, at its best and most valuable, comes from those who argue in the interests of crime victims and those who may be victimized. Their concerns for public safety must be taken seriously. To do that, we must offer something more than just lower sentences, but other ways to control crime, even (and perhaps especially) when crime rates are low. This can and should include proven plans to lower recidivism, including the promotion of education within prisons. It also can and should address root causes of crime, including poverty, as well. But beyond those important points, it must either assign a different role to law enforcement or argue for a reduced role for the police.

For example, in the narcotics field, there are options for addressing drug use other than broad legalization and a war on drugs, the two poles that are sometimes presented as our only options. One would be to attack the cash flow of the illegal narcotics trade rather than the labor of that industry, by forfeiting cash flow as it heads back to the source point of the trafficking.229 Such a tactic would make the business fail, driving up prices of illegal narcotics as supply shrank (at least temporarily).230

To remedy this, advocates must demand that candidates stake out positions on important criminal justice issues, lobby media outlets to question those candidates about criminal law, and press our own questions when we have the chance. It is crucial that advocates take their messages to those who will have the power to enact change at the time they are most likely to listen—when they are campaigning. Yes, that may mean going to Iowa,242 but to avoid this kind of engagement is to court irrelevance.

In 1988, George H.W. Bush was elected president over Democrat Michael Dukakis either because of or despite a racist appeal that became a legend. A group affiliated with his campaign, the National Security Political Action Committee, created an ad titled “Weekend Pass” that featured Willie Horton, an inmate who received a weekend furlough while Dukakis was governor of Massachusetts and used that opportunity to commit rape.243 Though the Bush campaign did not produce the ad itself, Bush campaign chairman Lee Atwater had said that “if we can make Willie Horton a household name, we will win the election.”244 The advertisement itself depicts a mug shot of Horton, a black man, as it describes the crimes he committed while on furlough.245

Few of us are good at admitting we were wrong.251 Prosecutors are particularly bad at it;252 criminal justice reforms almost always contain an implied but inherent criticism of what prosecutors have done. Too often prosecutors react to reform efforts by staunchly defending the power they have accumulated.253

Maintaining the top officials of the nation’s prosecutorial office as the only advisors to the president on criminal justice reform is ludicrous—the conflict is obvious.256 Two fixes to the problem are easily available, and can be created by the president through executive order. The first would be to create a single advisor position, similar to the role that the United States Trade Representative plays as an advisor outside of the Department of Commerce,257 or the National Security Advisor fulfills outside of the national intelligence agencies.258 Notably, at least one Democratic candidate for president in 2020—former prosecutor Senator Amy Klobuchar—embraced this idea.259

With either model, it would also allow for a new beginning and capabilities, including establishment of a data hub for metrics such as successful re-entry in support of a mission to promote public safety in the least costly way.262 At the very least, the DOJ’s chokehold on reform would finally be broken.

Finally, we must be bold in what we ask for, particularly in those periods in which reform seems most possible. Between 2009 and 2011, the first two years of the Obama administration, there was a tremendous and lost opportunity.268 Despite a motivated president (Obama) and Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress, the only significant advance in the field of criminal law through legislation was the tepid (yet important) Fair Sentencing Act, that reduced some crack sentences prospectively.269 Other legislative priorities—most prominently, the Affordable Care Act—took priority while time slipped away.270 We should have insisted on more.

We must also be more savvy about what we ask for. Too often, advocates seek the most obvious thing—for example, a reduction in the number of incarcerated people through sentencing reform. While that is important, seeking that kind of legislation is not the only thing we should be pursuing. To enact long-term change, we must also challenge decision structures and move to re-examine the very definitions of crimes.

Good and great work is being done in the field of criminal law. The First Step Act has improved thousands of lives, saved taxpayer money, and offers a bipartisan template for success. But if that is all we hope for, we are leaving far too much on the table when the stakes are measured in lives and freedom. This is not a time for brutal timidity, and it never was.

A unanimous Supreme Court last week held that people convicted of certain low-level crack cocaine offenses are not eligible for resentencing under the First Step Act, a sentencing reform bill passed in 2018 with bipartisan support that was meant to provide retroactive relief to those serving sentences for crack-cocaine offenses. According to the court, the result turned on a legislative omission — one that Congress can and must correct immediately in the interest of justice.

When the racially disparate impacts of the crack-powder sentences became apparent, the Congressional Black Caucus and criminal justice reform advocates began to call for eliminating the disparity. Bills to do so were introduced nearly every year from 1993 to 2009. In 2010, Congress finally addressed the problem — but merely reduced, and did not eliminate, the disparity. That bill, the Fair Sentencing Act, was not retroactive and the First Step Act was meant to make it so. As Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) stated during congressional hearings on the First Step Act, “Under the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, 21 U.S.C. § 841, thousands of people —‘90 percent [of them] African Americans, 96 percent [of them] Black and Latino’ — received harsh crack-cocaine sentences.”

Tarahrick Terry sought to be resentenced under the First Step Act, but the Supreme Court held that the plain language of the act rendered it inapplicable to his case. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, concurring in the unanimous decision, urged Congress to pass legislation to close the gap in the First Step Act that left Terry ineligible for resentencing.

Lawmakers should have made the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive in 2010. Eight years later, in trying to correct that error, they inadvertently left a loophole that continues to deny relief to some people. We urge Congress to pass the EQUAL Act introduced by Booker, to end the disparity. Congress should follow the Supreme Court’s direction without delay — it can and must fix this law.

The Senate voted 87-12in favor of the bill known as the First Step Act. The passage of the bill by the chamber is a significant victory for advocates on the left and the right, who have pressed for Congress to take action to lower the prison population.

For a while, it was unclear whether Trump would back measures to cut down on lengthy sentences. His first attorney general, Jeff Sessions, was staunchly opposed to the move.

This change would not be retroactive, so it would not help people already in prison serving life sentences under the three-strike rule. Some opponents of the bill have argued it does not go far enough to help people already affected by these laws.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

8613371530291

8613371530291