first step act 2018 safety valve for sale

The Act represents a dramatically different and enlightened approach to fighting crime that is focused on rehabilitation, reintegration, and sentencing reduction, rather than the tough-on-crime, lock-them-up rhetoric of the past.

Perhaps the Act’s most far-reaching change to sentencing law is its expansion of the application of the Safety Valve—the provision of law that reduces a defendant’s offense level by two and allows judges to disregard an otherwise applicable mandatory minimum penalty if the defendant meets certain criteria. It is aimed at providing qualifying low-level, non-violent drug offenders a means of avoiding an otherwise draconian penalty. In fiscal year 2017, nearly one-third of all drug offenders were found eligible for the Safety Valve.

Until the Act, one of the criteria for the Safety Valve was that a defendant could not have more than a single criminal history point. This generally meant that a defendant with as little as a single prior misdemeanor conviction that resulted in a sentence of more than 60 days was precluded from receiving the Safety Valve.

Section 402 of the Act relaxes the criminal history point criterion to allow a defendant to have up to four criminal history points and still be eligible for the Safety Valve (provided all other criteria are met). Now, even a prior felony conviction would not per se render a defendant ineligible from receiving the Safety Valve so long as the prior felony did not result in a sentence of more than 13 months’ imprisonment.

Importantly, for purposes of the Safety Valve, prior sentences of 60 days or less, which generally result in one criminal history point, are never counted. However, any prior sentences of more than 13 months, or more than 60 days in the case of a violent offense, precludes application of the Safety Valve regardless of whether the criminal history points exceed four.

These changes to the Safety Valve criteria are not retroactive in any way, and only apply to convictions entered on or after the enactment of the Act. Despite this, it still is estimated that these changes to the Safety Valve will impact over 2,000 offenders annually.

Currently, defendants convicted of certain drug felonies are subject to a mandatory minimum 20 years’ imprisonment if they previously were convicted of a single drug felony. If they have two or more prior drug felonies, then the mandatory minimum becomes life imprisonment. Section 401 of the Act reduces these mandatory minimums to 15 years and 25 years respectively.

These amendments apply to any pending cases, except if sentencing already has occurred. Thus, they are not fully retroactive. Had they been made fully retroactive, it is estimated they would have reduced the sentences of just over 3,000 inmates. As it stands, these reduced mandatory minima are estimated to impact only 56 offenders annually.

Section 403 of the Act eliminates the so-called “stacking” of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A) penalties. Section 924(c) provides for various mandatory consecutive penalties for the possession, use, or discharge of a firearm during the commission of a felony violent or drug offense. However, for a “second or subsequent conviction” of 924(c), the mandatory consecutive penalty increases to 25 years.

Occasionally, the Government charges a defendant with multiple counts of 924(c), which results in each count being sentenced consecutive to each other as well as to the underlying predicate offense. For example, a defendant is charged with two counts of drug trafficking and two counts of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A)(i), which requires a consecutive 5 years’ imprisonment to the underlying offense for mere possession of a firearm during the commission of the drug offense. At sentencing, the Court imposes 40 months for the drug trafficking offenses. As a result of the first § 924(c)(1)(A)(i) conviction, the Court must impose a consecutive 60 months (5 years). But what about the second § 924(c)(1)(A)(i) conviction? In such situations, courts have been treating the second count as a “second or subsequent conviction.” As such, the 60-month consecutive sentence becomes a 300 month (25 years) consecutive sentence. In our hypothetical, then, the sentencing court would impose a total sentence of 400 months (40+60+300) inasmuch as the second 924(c) count was a “second or subsequent conviction.”

Now, under the Act, to avoid such an absurd and draconian result, Congress has clarified that the 25-year mandatory consecutive penalty only applies “after a prior conviction under this subsection has become final.” Thus, the enhanced mandatory consecutive penalty no longer can be applied to multiple counts of 924(c) violations.

Finally, Section 404 of the Act makes the changes brought about by the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 fully retroactive. As the U.S. Sentencing Commission’s “2015 Report to Congress: Impact of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010,” explained: “The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (FSA), enacted August 3, 2010, reduced the statutory penalties for crack cocaine offenses to produce an 18-to-1 crack-to-powder drug quantity ratio. The FSA eliminated the mandatory minimum sentence for simple possession of crack cocaine and increased statutory fines. It also directed the Commission to amend the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines to account for specified aggravating and mitigating circumstances in drug trafficking offenses involving any drug type.”

While the Act now makes the FSA fully retroactive, those prisoners who already have sought a reduction under the FSA and either received one, or their application was otherwise adjudicated on the merits, are not eligible for a second bite at the apple. It is estimated that full retroactive application of the FSA will impact 2,660 offenders.

Reducing the severity and frequency of some draconian mandatory minimum penalties, increasing the applicability of the safety valve, and giving full retroactive effect to the FSA signals a more sane approach to sentencing, which will help address prison overpopulation, while ensuring scarce prison space is reserved only for the more dangerous offenders.

Mark H. Allenbaugh, co-founder of Sentencing Stats, LLC, is a nationally recognized expert on federal sentencing, law, policy, and practice. A former staff attorney for the U.S. Sentencing Commission, he is a co-editor of Sentencing, Sanctions, and Corrections: Federal and State Law, Policy, and Practice (2nd ed., Foundation Press, 2002). He can be reached at mark@sentencingstats.com.

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

On December 21, 2018, President Trump signed into law the First Step Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-391). The act was the culmination of several years of congressional debate about what Congress might do to reduce the size of the federal prison population while also creating mechanisms to maintain public safety.

This report provides an overview of the provisions of the First Step Act. The act has three major components: (1) correctional reform via the establishment of a risk and needs assessment system at BOP, (2) sentencing reform that involved changes to penalties for some federal offenses, and (3) the reauthorization of the Second Chance Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-199). The act also contains a series of other criminal justice-related provisions that include, for example, changes to the way good time credits are calculated for federal prisoners, prohibiting the use of restraints on pregnant inmates, expanding the market for products made by the Federal Prison Industries, and requiring BOP to aid prisoners with obtaining identification before they are released.

The correctional reform component of the First Step Act involves the development and implementation of a risk and needs assessment system (system) at BOP.

The act requires DOJ to develop the system to be used by BOP to assess the risk of recidivism of federal prisoners and assign prisoners to evidence-based recidivism reduction programsdetermine the risk of recidivism of each prisoner during the intake process and classify each prisoner as having a minimum, low, medium, or high risk;

reassign prisoners to appropriate recidivism reduction programs or productive activities based on their reassessed risk of recidivism to ensure that all prisoners have an opportunity to reduce their risk classification, that the programs address prisoners" criminogenic needs, and that all prisoners are able to successfully participate in such programs;

conduct ongoing research and data analysis on (1) evidence-based recidivism reduction programs related to the use of risk and needs assessment, (2) the most effective and efficient uses of such programs, (3) which programs are the most effective at reducing recidivism, and the type, amount, and intensity of programming that most effectively reduces the risk of recidivism, and (4) products purchased by federal agencies that are manufactured overseas and could be manufactured by prisoners participating in a prison work program without reducing job opportunities for other workers in the United States;

annually review and validate the risk and needs assessment system, including an evaluation to ensure that assessments are based on dynamic risk factors (i.e., risk factors that can change); validate any tools that the system uses; and evaluate the recidivism rates among similarly classified prisoners to identify any unwarranted disparities, including disparities in such rates among similarly classified prisoners of different demographic groups, and make any changes to the system necessary to address any that are identified; and

Under the act, the system is required to provide guidance on the type, amount, and intensity of recidivism reduction programming and productive activities to which each prisoner is assigned, including information on which programs prisoners should participate in based on their criminogenic needs and the ways that BOP can tailor programs to the specific criminogenic needs of each prisoner to reduce their risk of recidivism. The system is also required to provide guidance on how to group, to the extent practicable, prisoners with similar risk levels together in recidivism reduction programming and housing assignments.

The act requires BOP, when developing the system, to take steps to screen prisoners for dyslexia and to provide programs to treat prisoners who have it.

Within 180 days of DOJ releasing the system, BOP is required tocomplete the initial risk and needs assessment for each prisoner (including for prisoners who were incarcerated before the enactment of the First Step Act);

begin to expand the recidivism reduction programs and productive activities available at BOP facilities and add any new recidivism reduction programs and productive activities necessary to effectively implement the system; and

BOP is required to expand recidivism reduction programming and productive activities capacity so that all prisoners have an opportunity to participate in risk reduction programs within two years of BOP completing initial risk and needs assessments for all prisoners. During the two-year period when BOP is expanding recidivism reduction programs and productive activities, prisoners who are nearing their release date are given priority for placement in such programs.

BOP is required to provide all prisoners with the opportunity to participate in recidivism reduction programs that address their criminogenic needs or productive activities throughout their term of incarceration. High- and medium-risk prisoners are to have priority for placement in recidivism reduction programs, while the program focus for low-risk prisoners is on participation in productive activities.

Prisoners who successfully participate in recidivism reduction programming or productive activities are required to be reassessed not less than annually, and high- and medium-risk prisoners who have less than five years remaining until their projected release date are required to have more frequent reassessments. If the reassessment shows that a prisoner"s risk of recidivating or specific needs have changed, BOP is required to reassign the prisoner to recidivism reduction programs or productive activities consistent with those changes.

The First Step Act requires the use of incentives and rewards for prisoners to participate in recidivism reduction programs, including the following:additional phone privileges, and if available, video conferencing privileges, of up to 30 minutes a day, and up to 510 minutes a month;

Under the act, prisoners who successfully complete recidivism reduction programming are eligible to earn up to 10 days of time credits for every 30 days of program participation. Minimum and low-risk prisoners who successfully completed recidivism reduction or productive activities and whose assessed risk of recidivism has not increased over two consecutive assessments are eligible to earn up to an additional five days of time credits for every 30 days of successful participation. However, prisoners serving a sentence for a conviction of any one of multiple enumerated offenses are ineligible to earn additional time credits regardless of risk level, though these prisoners are eligible to earn the other incentives and rewards for program participation outlined above. Offenses that make prisoners ineligible to earn additional time credits can generally be categorized as violent, terrorism, espionage, human trafficking, sex and sexual exploitation, repeat felon in possession of firearm, certain fraud, or high-level drug offenses. Prisoners who are subject to a final order of removal under immigration law are ineligible for additional earned time credits provided by the First Step Act.

Prisoners cannot retroactively earn time credits for programs they completed prior to the enactment of the First Step Act, and they cannot earn time credits for programs completed while detained pending adjudication of their cases.

The act requires BOP to develop guidelines for reducing time credits prisoners earned under the system for violating institutional rules or the rules of recidivism reduction programs and productive activities. The guidelines must also include a description of a process for prisoners to earn back any time credits they lost due to misconduct.

the prisoner has been determined to be a minimum or low risk to recidivate based on his/her last two assessments, or has had a petition to be transferred to prerelease custody approved by the warden, after the warden"s determination that the prisoner (1) would not be a danger to society if transferred to prerelease custody, (2) has made a good faith effort to lower his/her recidivism risk through participation in recidivism reduction programs or productive activities, and (3) is unlikely to recidivate.

Prisoners who are placed on prerelease custody on home confinement are subject to a series of conditions. Per the act, prisoners on home confinement are required to have 24-hour electronic monitoring that enables the identification of their location and the time, and must remain in their residences, except togo to work or participate in job-seeking activities,

When monitoring adherence to the conditions of prerelease custody, BOP is required, to the extent practicable, to reduce the restrictiveness of those conditions for prisoners who demonstrate continued compliance with their conditions.

Two years after the enactment of the First Step Act, and each year thereafter for the next five years, DOJ is required to submit a report to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees and the House and Senate Subcommittees on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies (CJS) Appropriations that includes information onthe types and effectiveness of recidivism reduction programs and productive activities provided by BOP, including the capacity of each program and activity at each prison and any gaps or shortages in capacity of such programs and activities;

the recidivism rates of prisoners released from federal prison, based on the following criteria: (1) the primary offense of conviction; (2) the length of the sentence imposed and served; (3) the facility or facilities in which the prisoner"s sentence was served; (4) the type of recidivism reduction programming; (5) prisoners" assessed and reassessed risk of recidivism; and (6) the type of productive activities;

any budgetary savings that have resulted from the implementation of the act, and a strategy for investing those savings in other federal, state, and local law enforcement activities and expanding recidivism reduction programs and productive activities at BOP facilities.

Within two years of the enactment of the First Step Act, the Independent Review Committee is required to submit a report to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees and the House and Senate CJS Appropriations Subcommittees that includesa list of all offenses that make prisoners ineligible for earned time credits under the system, and the number of prisoners excluded for each offense by age, race, and sex;

the number of prisoners ineligible for earned time credits under the system who did not participate in recidivism reduction programming or productive activities by age, race, and sex; and

whether BOP is offering the type, amount, and intensity of recidivism reduction programs and productive activities that allow prisoners to earn the maximum amount of additional time credits for which they are eligible;

The First Step Act authorizes $75 million per fiscal year from FY2019 to FY2023 for DOJ to establish and implement the system; 80% of this funding is to be directed to BOP for implementation.

The First Step Act makes several changes to federal sentencing law. The act reduced the mandatory minimum sentences for certain drug offenses, expanded the scope of the safety valve, eliminated the stacking provision, and made the provisions of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-220) retroactive.

The act adjusts the mandatory minimum sentences for certain drug traffickers with prior drug convictions. The act reduces the 20-year mandatory minimum (applicable where the offender has one prior qualifying conviction) to a 15-year mandatory minimum and reduces the life sentence mandatory minimum (applicable where the offender has two or more prior qualifying convictions) to a 25-year mandatory minimum.serious drug felonyserious violent felonyfelony drug offense.

The act makes drug offenders with minor criminal records eligible for the safety valve provision, which previously applied only to offenders with virtually spotless criminal records.

The act eliminates stacking by providing that the 25-year mandatory minimum for a "second or subsequent" conviction for use of a firearm in furtherance of a drug trafficking crime or a violent crime applies only where the offender has a prior conviction for use of a firearm that is already final.

The First Step Act authorizes courts to apply retroactively the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which increased the threshold quantities of crack cocaine sufficient to trigger mandatory minimum sentences, by resentencing qualified prisoners as if the Fair Sentencing Act had been in effect at the time of their offenses.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act of 2018 (Title V of the First Step Act) reauthorizes many of the grant programs that were initially authorized by the Second Chance Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-199). The Second Chance Reauthorization Act also reauthorized a BOP pilot program to provide early release to elderly prisoners.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amends the authorization for the Adult and Juvenile State and Local Offender Demonstration Program so grants can be awarded to states, local governments, territories, or Indian tribes, or any combination thereof, in partnership with interested persons (including federal correctional officials), service providers, and nonprofit organizations, for the strategic planning and implementation of reentry programs. The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amended the authorization for this program to allow grants to be used for reentry courts and promoting employment opportunities consistent with a transitional jobs strategy in addition to the purposes for which grants could already be awarded.

The act also amended the Second Chance Act authorizing legislation for the program to allow DOJ to award both planning and implementation grants. DOJ is required to develop a procedure to allow applicants to submit a single grant application when applying for both planning and implementation grants.

providing a plan for analyzing the barriers (e.g., statutory, regulatory, rules-based, or practice-based) to reentry for ex-offenders in the applicants" communities;

Under the amended program, applicants for implementation grants would be required to develop a strategic reentry plan that contains measurable three-year performance outcomes. Applicants would be required to develop a feasible goal for reducing recidivism using baseline data collected through the partnership with the local evaluator. Applicants are required to use, to the extent practicable, random assignment and controlled studies, or rigorous quasi-experimental studies with matched comparison groups, to determine the effectiveness of the program.

As authorized by the Second Chance Act, grantees under the Adult and Juvenile State and Local Offender Demonstration program are required to submit annual reports to DOJ that identify the specific progress made toward achieving their strategic performance outcomes, which they are required to submit as a part of their reentry strategic plans. Data on performance measures only need to be submitted by grantees that receive an implementation grant. The act repeals some performance outcomes (i.e., increased housing opportunities, reduction in substance abuse, and increased participation in substance abuse and mental health services) and adds the following outcomes:increased number of staff trained to administer reentry services;

The act allows applicants for implementation grants to include a cost-benefit analysis as a performance measure under their required reentry strategic plan.

The Second Chance Act authorized DOJ to make grants to states, local governments, and Indian tribes to develop, implement, and expand the use of family-based substance abuse treatment programs as an alternative to incarceration for parents who were convicted of nonviolent drug offenses and to provide prison-based family treatment programs for incarcerated parents of minor children.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amends the authorization for the program to allow grants to be awarded to nonprofit organizations and requires DOJ to give priority consideration to nonprofit organizations that demonstrate a relationship with state and local criminal justice agencies, including the judiciary and prosecutorial agencies or local correctional agencies.

The Second Chance Act authorized a grant program to evaluate and improve academic and vocational education in prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities. This program authorizes DOJ to make grants to states, units of local government, territories, Indian tribes, and other public and private entities to identify and implement best practices related to the provision of academic and vocational education in prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities. Grantees are required to submit reports within 90 days of the end of the final fiscal year of a grant detailing the progress they have made, and to allow DOJ to evaluate improved academic and vocational education methods carried out with grants provided under this program.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amends the authorizing legislation for this program to require DOJ to identify and publish best practices relating to academic and vocational education for offenders in prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities. In identifying best practices, the evaluations conducted under this program must be considered.

The Second Chance Act authorized DOJ to make grants to states, units of local government, territories, and Indian tribes to provide technology career training for prisoners. Grants could be awarded for programs that establish technology careers training programs for inmates in a prison, jail, or juvenile detention facility.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act expanded the scope of the program to allow grant funds to be used to provide any career training to those who are soon to be released and during transition and reentry into the community. The act makes nonprofit organizations an eligible applicant under the program. Under the legislation, grants funds could be used to provide subsidized employment if it is a part of a career training program. The act also requires DOJ to give priority consideration to any application for a grant thatprovides an assessment of local demand for employees in the geographic area to which offenders are likely to return,

The Second Chance Act authorized DOJ to make grants to states, units of local governments, territories, and Indian tribes in order to improve drug treatment programs in prisons and reduce the post-prison use of alcohol and other drugs by long-term users under correctional supervision. Grants may be used to continue or improve existing drug treatment programs, develop and implement programs for long-term users, provide addiction recovery support services, or establish medication assisted treatment (MAT) services as part of any drug treatment program offered to prisoners.

The Second Chance Act authorized DOJ to make grants to nonprofit organizations and Indian tribes to provide mentoring and other transitional services for offenders being released into the community. Funds could be used for mentoring programs in prisons or jails and during reentry, programs providing transition services during reentry, and programs providing training for mentors on the criminal justice system and victims issues.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amends the authorization for the program to pivot the focus toward providing community-based transitional services to former inmates returning to the community. Reflecting the change in focus, the reauthorization changed the name of the program to "Community-based Mentoring and Transitional Services Grants to Nonprofit Organizations." The act specifies the transitional services that can be provided to returning inmates under the program, including educational, literacy, vocational, and the transitional jobs strategy; substance abuse treatment and services; coordinated supervision and services for offenders, including physical health care and comprehensive housing and mental health care; family services; and validated assessment tools to assess the risk factors of returning prisoners.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act reauthorized and expanded the scope of a pilot program initially authorized under the Second Chance Act that allowed BOP to place certain elderly nonviolent offenders on home confinement to serve the remainder of their sentences. BOP was authorized to conduct this pilot program at one facility for FY2009 and FY2010. An offender eligible to be released through the program had to meet the following requirements:at least 65 years old;

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act reestablishes the pilot program and allows BOP to operate it at multiple facilities from FY2019 to FY2023. The act also modifies the eligibility criteria for elderly offenders so that any offenders who are at least 60 year old and have served two-thirds of their sentences can be placed on home confinement.

The act also expands the program so that terminally ill offenders can be placed on home confinement. Eligibility criteria for home confinement for terminally ill offenders under the pilot program is the same as that for elderly offenders, except that terminally ill offenders of any age and who have served any portion of their sentences, even life sentences, are eligible for home confinement. Terminally ill prisoners are those who are deemed by a BOP medical doctor to need care at a nursing home, intermediate care facility, or assisted living facility, or those who have been diagnosed with a terminal illness.

The Second Chance Act authorized appropriations for a series of reentry-related research projects, including the following:a study by the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) identifying the number and characteristics of children with incarcerated parents and their likelihood of engaging in criminal activity;

studies by BJS to determine the characteristics of individuals who return to prison, jail, or a juvenile facility (including which individuals pose the highest risk to the community);

collecting data and developing best practices concerning the communication and coordination between state corrections and child welfare agencies, to ensure the safety and support of children of incarcerated parents.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act reauthorizes appropriations for these research projects at $5 million for each fiscal year from FY2019 to FY2023.

Within five years of the enactment of the Second Chance Reauthorization Act, NIJ is required to evaluate grants used by DOJ to support reentry and recidivism reduction programs at the state, local, tribal, and federal levels. Specifically, NIJ is required to evaluate the following:whether the programs are cost-effective, including the extent to which the programs improved reentry outcomes;

NIJ is required to identify outcome measures, including employment, housing, education, and public safety, that are the goals of programs authorized by the Second Chance Act and metrics for measuring whether those programs achieved the intended results. As a condition of receiving funding under programs authorized by the Second Chance Act, grantees are required to collect and report data to DOJ related to those metrics.

NIJ is required to make data collected during evaluations of Second Chance Act programs publicly available in a manner that protects the confidentiality of program participants and is consistent with applicable law. NIJ is also required to make the final evaluation reports publicly available.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act requires BOP to develop policies for wardens of prisons and community-based facilities to enter into recidivism-reducing partnerships with nonprofit and other private organizations, including faith-based and community-based organizations to deliver recidivism reduction programming.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act repealed the authorization for the State, Tribal, and Local Reentry Courts program (Section 111 of the Second Chance Act), the Responsible Reintegration of Offenders program (Section 212), and the Study on the Effectiveness of Depot Naltrexone for Heroin Addiction program (Section 244).

In addition to correctional and sentencing reform and reauthorizing the Second Chance Act, the First Step Act contained a series of other criminal justice-related provisions.

The act amended 18 U.S.C. Section 3624(b) so that federal prisoners can earn up to 54 days of good time credit for every year of their imposed sentence rather than for every year of their sentenced served. Prior to the amendment, BOP interpreted the good time credit provision in Section 3624(b) to mean that prisoners are eligible to earn 54 days of good time credit for every year they serve. For example, this means that an offender who was sentenced to 10 years in prison and earned the maximum good time credits each year could be released after serving eight years and 260 days, having earned 54 days of good time credit for each year of the sentence served, but in effect, only 47 days of good time credit for every year of the imposed sentence.

The act requires BOP to provide a secure storage area outside of the secure perimeter of a correctional institution for qualified law enforcement officers employed by BOP to store firearms or allow this class of employees to store firearms in their personal vehicles in lockboxes approved by BOP. The act also requires BOP, notwithstanding any other provision of law, to allow these same employees to carry concealed firearms on prison grounds but outside of the secure perimeter of the correctional institution.

The act prohibits BOP or the U.S. Marshals Service (USMS) from using restraints on pregnant inmates in their custody. The prohibition on the use of restraints begins on the date that pregnancy is confirmed by a healthcare professional. The restriction ends when the inmate completes postpartum recovery.

The prohibition on the use of restraints does not apply if the inmate is determined to be an immediate and credible flight risk or poses an immediate and serious threat of harm to herself or others that cannot be reasonably prevented by other means, or a healthcare professional determines that the use of restraints is appropriate for the medical safety of the inmate. Only the least restrictive restraints necessary to prevent escape or harm can be used. The exception to the use of restraints does not permit BOP or USMS to use them around the ankles, legs, or waist of an inmate; restrain an inmate"s hands behind her back; use four-point restraints; or attach an inmate to another inmate. Upon the request of a healthcare professional, correctional officials or deputy marshals shall refrain from using restraints on an inmate or shall remove restraints used on an inmate.

If restraints are used on a pregnant inmate, the correctional official or deputy marshal who used the restraints is required to submit a report within 30 days to BOP or USMS, and the healthcare provider responsible for the inmate"s health and safety, that describes the facts and circumstances surrounding the use of the restraints, including the reason(s) for using them; the details of their use, including the type of restraint and length of time they were used; and any observable physical effects on the prisoner.

The act amends 18 U.S.C. Section 3621(b) to require BOP to house prisoners in facilities as close to their primary residence as possible, and to the extent practicable, within 500 driving miles, subject to a series of considerations. When making decisions about where to house a prisoner, BOP must consider bedspace availability, the prisoner"s security designation, the prisoner"s programmatic needs, the prisoner"s mental and medical health needs, any request made by the prisoner related to faith-based needs, recommendations of the sentencing court, and other security concerns. BOP is also required, subject to these considerations and a prisoner"s preference for staying at his/her current facility or being transferred, to transfer a prisoner to a facility closer to his/her primary residence even if the prisoner is currently housed at a facility within 500 driving miles.

The act amends 18 U.S.C. Section 3624(c)(2) to require BOP, to the extent practicable, to place prisoners with lower risk levels and lower needs on home confinement for the maximum amount of time permitted under this paragraph. Under Section 3624(c)(2), BOP is authorized to place prisoners in prerelease custody on home confinement for 10% of the term of imprisonment or six months, whichever is shorter.

The act amends 18 U.S.C. Section 3582(c) regarding when a court can modify a term of imprisonment once it is imposed. Under Section 3582(c)(1)(A), a court, upon a petition from BOP, can reduce a prisoner"s sentence and impose a term of probation or supervised release, with or without conditions, equal to the amount of time remaining on the prisoner"s sentence if the court finds that "extraordinary and compelling reasons warrant such a reduction," or the prisoner is at least 70 years of age, the prisoner has served at least 30 years of his/her sentence, and a determination has been made by BOP that the prisoner is not a danger to the safety of any other person or the community. This is sometimes referred to as compassionate release. The amendments made by the act allow the court to reduce a prisoner"s sentence under Section 3582(c)(1)(A) upon a petition from BOP or the prisoner if the prisoner has fully exhausted all administrative rights to appeal a failure by BOP to bring a motion on the prisoner"s behalf or upon a lapse of 30 days from the receipt of such a request by the warden of the prisoner"s facility, whichever is earlier.

The act also requires BOP within 72 hours of a prisoner being diagnosed with a terminal illness to notify the prisoner"s attorney, partner, and family about the diagnosis and inform them of their option to submit a petition for compassionate release on the prisoner"s behalf. Within seven days, BOP is required to provide the prisoner"s partner and family with an opportunity to visit. BOP is also required to provide assistance to the prisoner with drafting and submitting a petition for compassionate release if such assistance is requested by the prisoner or the prisoner"s attorney, partner, or family. BOP is required to process requests for compassionate release within 14 days.

The act also requires BOP to submit annual reports to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees that provides data on how BOP is processing applications for compassionate release.

The act amends the authorization for the federal prisoner reentry initiative (34 U.S.C. Section 60541(b)) to require BOP to assist prisoners and offenders who were sentenced to a period of community confinement

The act also amends 18 U.S.C. Section 4042(a) to require BOP to establish prerelease planning procedures to help prisoners apply for federal and state benefits and obtain identification, including a social security card, driver"s license or other official photo identification, and birth certificate. BOP is required to help prisoners secure these benefits, subject to any limitations in law, prior to being released. The act also amends Section 4042(a) to require prerelease planning to include any individuals who only served a sentence of community confinement.

The act authorizes the Federal Prison Industries (FPI, also known by its trade name, UNICOR) to sell products to public entities for use in correctional facilities, disaster relief, or emergency response; to the District of Columbia government; and to nonprofit organizations.

The act also requires BOP to set aside 15% of the wages paid to prisoners with FPI work assignments in a fund that will be payable to the prisoner upon release to aid with the cost of transitioning back into the community.

The act requires BOP to provide training to correctional officers and other BOP employees (including correctional officers and employees of facilities that contract with BOP to house prisoners) on how to de-escalate encounters between a law enforcement officer or an officer or employee of BOP and a civilian or a prisoner, and how to identify and appropriately respond to incidents that involve people with mental illness or other cognitive deficits.

Within 90 days of enactment of the act, BOP is required to submit a report to the House and Senate Judiciary and Appropriations Committees that assesses the availability of, and the capacity of BOP to provide, evidence-based treatment to prisoners with opioid and heroin abuse problems, including MAT, where appropriate. As a part of the report, BOP is required to provide a plan to expand access to evidence-based treatment for prisoners with heroin and opioid abuse problems, including MAT, where appropriate. After submitting the report, BOP is required to execute the plan it outlines in the report.

The act places a similar requirement on the Administrative Office of the United States Courts (AOUSC) regarding evidence-based treatment for opioid and heroin abuse for prisoners serving a term of supervised release. AOUSC has 120 days after enactment to submit its report to the House and Senate Judiciary and Appropriations Committees.

The act requires BOP to establish two pilot programs that are to run for five years in at least 20 facilities. The first is a mentoring program that is to pair youth with volunteer mentors from faith-based or community organizations.

The act requires BJS to expand data collected under its National Prisoner Statistics program to include 26 new data elements related to federal prisoners. Some of the data the act requires BJS to collect include the following:the number of prisoners who are veterans;

the number of prisoners enrolled in recidivism reduction programs and productive activities at each BOP facility, broken down by risk level and by program, and the number of those enrolled prisoners who successfully completed each program.

Starting one year after the enactment of the act, BJS is required to submit an annual report to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees for a period of seven years that contains the data specified in the act.

The act requires BOP to provide tampons and sanitary napkins that meet industry standards to prisoners for free and in a quantity that meets the healthcare needs of each prisoner.

The act requires the Attorney General to coordinate with the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, the Secretaries of Labor, Education, Health and Human Services, Veterans Affairs, and Agriculture, and the heads of other relevant federal agencies, as well as interested persons, service providers, nonprofit organizations, and state, tribal, and local governments, on federal reentry policies, programs, and activities, with an emphasis on evidence-based practices and the elimination of duplication of services.

The Attorney General, in consultation with the secretaries specified in the act, is required to submit a report to Congress within two years of the enactment of the act that summarizes the achievements of the coordination, and includes recommendations for Congress on how to further reduce barriers to successful reentry.

The act prohibits juvenile facilities from using room confinement for discipline, punishment, retaliation, or any reason other than as a temporary response to a covered juvenile"s behavior that poses a serious and immediate risk of physical harm to any individual.

Juvenile facilities are required to try to use less restrictive techniques, such as talking with the juvenile in an attempt to de-escalate the situation or allowing a mental health professional to talk to the juvenile, before placing the juvenile in room confinement. If the less restrictive techniques do not work and the juvenile is placed in room confinement, the staff of the juvenile facility is required to tell the juvenile why he/she is being placed in room confinement. Staff are also required to inform the juvenile that he/she will be released from room confinement as soon as he/she regains self-control and no longer poses a threat of physical harm to himself/herself or others. If a juvenile who poses a threat of harm to others does not sufficiently regain self-control, staff must inform the juvenile that he/she will be released within three hours of being placed in room confinement, or in the case of a juvenile who poses a threat of harm to himself/herself, that he/she will be released within 30 minutes of being placed in room confinement. If after the maximum period of confinement allowed the juvenile continues to pose a threat of physical harm to himself/herself or others, the juvenile is to be transferred to another juvenile facility or another location in the current facility where services can be provided to him/her. If a qualified mental health professional believes that the level of crisis services available to the juvenile are not adequate, the staff at the juvenile facility is to transfer the juvenile to a facility that can provide adequate services. The act prohibits juvenile facilities from using consecutive periods of room confinement on juveniles.

In December 2018, President Trump signed into law the First Step Act, which mostly involves prison reform, but also includes some sentencing reform provisions.

The key provision of the First Step Act that relates to sentencing reform concerns the “safety valve” provision of the federal drug trafficking laws. The safety valve allows a court to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum sentence for the crime, and to reduce the person’s offense level under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines by two points.

The First Step Act increases the availability of the safety valve by making it easier to meet the first requirement—little prior criminal history. Before the First Step Act, a person could have no more than one criminal history point. This generally means no more than one prior conviction in the last ten years for which the person received either probation or less than 60 days of prison time.

Section 402 of the First Step Act changes this. Now, a person is eligible for the safety valve if, in addition to meeting requirements 2-5 above, the defendant does not have:

This news has been published for the above source. Kiss PR Brand Story Press Release News Desk was not involved in the creation of this content. For any service, please contact https://story.kisspr.com.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8233847/653535250.jpg)

In December 2018, President Trump signed into law the First Step Act, which mostly involves prison reform, but also includes some sentencing reform provisions.

The key provision of the First Step Act that relates to sentencing reform concerns the “safety valve” provision of the federal drug trafficking laws. The safety valve allows a court to sentence a person below the mandatory minimum sentence for the crime, and to reduce the person’s offense level under the Federal Sentencing Guidelines by two points.

The First Step Act increases the availability of the safety valve by making it easier to meet the first requirement—little prior criminal history. Before the First Step Act, a person could have no more than one criminal history point. This generally means no more than one prior conviction in the last ten years for which the person received either probation or less than 60 days of prison time.

Section 402 of the First Step Act changes this. Now, a person is eligible for the safety valve if, in addition to meeting requirements 2-5 above, the defendant does not have:

This news has been published for the above source. Kiss PR Brand Story Press Release News Desk was not involved in the creation of this content. For any service, please contact https://story.kisspr.com.

The Act requires the submission of several reports to review the BOP"s implementation of the law and assess the effects of the new risk and needs assessment system.

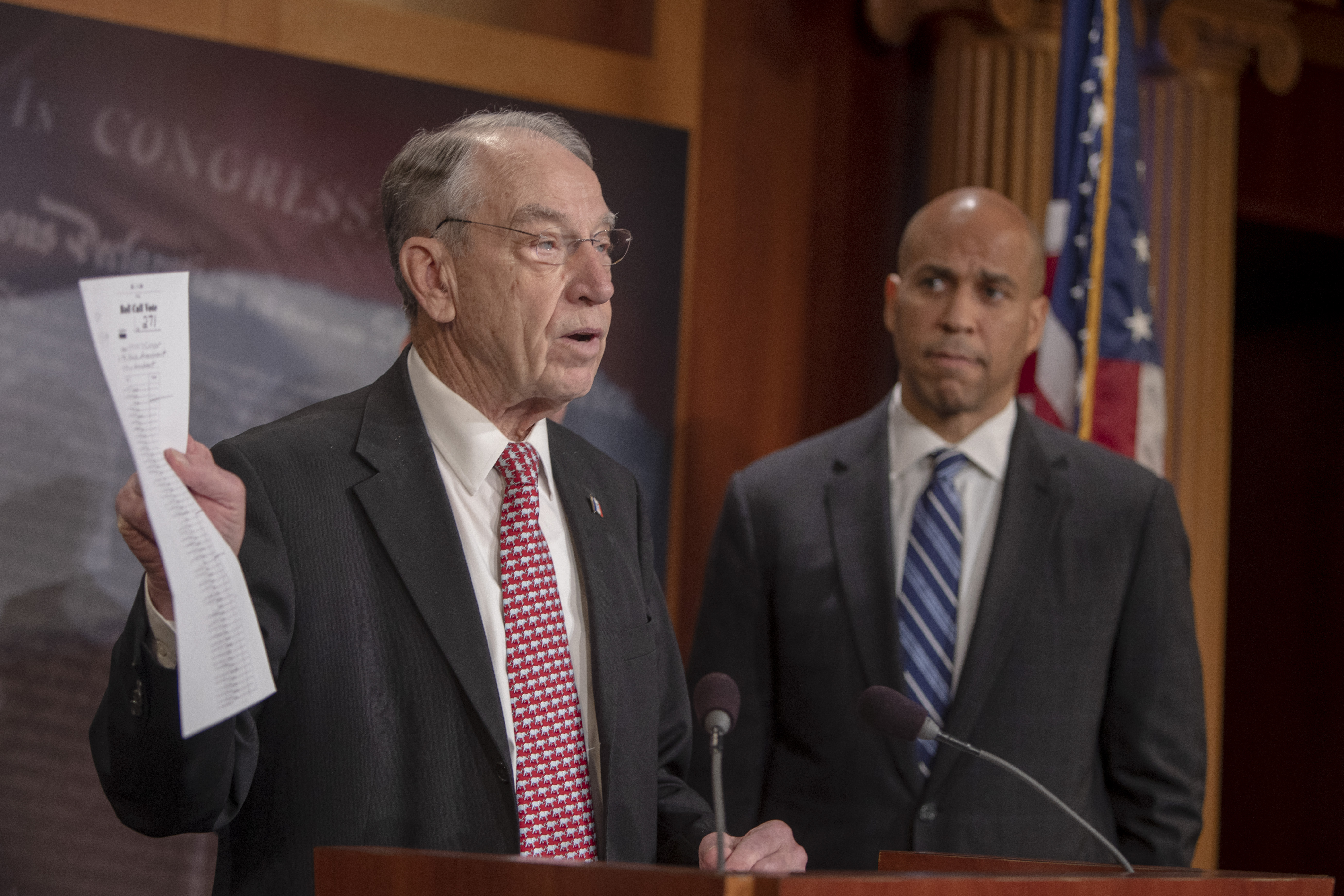

“This legislation reformed sentencing laws that have wrongly and disproportionately harmed the African-American community,” Trump said. “The First Step Act gives nonviolent offenders the chance to reenter society as productive, law-abiding citizens. Now, states across the country are following our lead. America is a nation that believes in redemption.”

The First Step Act, which passed with overwhelming support from Republicans and Democrats, takes modest steps to alter the federal criminal justice system and ease very punitive prison sentences at the federal level. It affects only the federal system — which, with about 181,000 imprisoned people, holds a small but significant fraction of the US jail and prison population of 2.1 million.

The legislation went through a lot of changes compared to when it was first introduced last year, when a version of it passed the Republican-controlled House of Representatives. Back then, the legislation made no effort to cut the length of prison sentences on the front end, although it did take some steps to encourage rehabilitation programs in prison that inmates could use, in effect, to reduce how long they’re in prison. But Senate Democrats and other reformers took issue with the legislation’s limited scope and managed to add changes that will ease prison sentences, at least mildly.

That doesn’t mean the law skated by without opposition. Some Senate Republicans, led by Sen. Tom Cotton of Arkansas, took issue with the mild reforms in the First Step Act, even as Republican senators like Chuck Grassley (IA) and Lindsey Graham (SC) came on board.

But the First Step Act ultimately passed with huge support in both the House and Senate, becoming the most significant criminal justice reform law at the federal level in years.

The law makes retroactive the reforms enacted by the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced the disparity between crack cocaine and powder cocaine sentences at the federal level. This will affect nearly 2,600 federal inmates, according to the Marshall Project.

The law takes several steps to ease mandatory minimum sentences under federal law. It expands the “safety valve” that judges can use to avoid handing down mandatory minimum sentences. It eases a “three strikes” rule so people with three or more convictions, including for drug offenses, automatically get 25 years instead of life, among other changes. It restricts the current practice of stacking gun charges against drug offenders to add possibly decades to prison sentences. All of these changes will lead to shorter prison sentences in the future.

The law increases “good time credits” that inmates can earn. Inmates who avoid a disciplinary record can currently get credits of up to 47 days per year incarcerated. The law increases the cap to 54, allowing well-behaved inmates to cut their prison sentences by an additional week for each year they’re incarcerated. The change applies retroactively, which will allow some prisoners — as many as 4,000, according to supporters — to qualify for an earlier release fairly soon (although there have been some problems securing early release so far, thanks to how the legislation was written).

But algorithms can perpetuate racial and class disparities that are already deeply embedded in the criminal justice system. For instance, an algorithm that excludes someone from earning credits due to previous criminal history may overlook that black and poor people are more likely to be incarcerated for crimes even when they’re not more likely to actually commit those crimes. So although the law puts checks on the algorithm, it’s turned into a controversial portion of the law — even among criminal justice reformers.

Nothing in the legislation is that groundbreaking, particularly compared to the state-level reforms that have passed in recent years, from reduced prison sentences across the board to the defelonization of drug offenses to marijuana legalization. That’s one reason the law is dubbed a “first step.” Still, it’s a step — the kind that Congress hasn’t taken in years, as it’s debated criminal justice reform but failed to follow through.

For example, Cotton argued that “productive activities” are defined so vaguely in the bill that federal inmates could earn early release by watching TV or doing other leisurely activities.

Cotton also claimed that some high-level offenders would be eligible for early release under the First Step Act, because it didn’t exclude, for example, someone convicted of threatening to assault, kidnap, or murder a judge from earning time credits.

But Jessica Jackson Sloan, the national director and co-founder of the criminal justice reform group #Cut50, argued that this misunderstood how the law is applied in reality: Someone convicted of threatening to kidnap a judge would also be convicted on kidnapping charges more generally — and those general charges would lead to exclusion under the First Step Act.

Still, the opposition from some Republicans, including Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX), was enough to make McConnell skeptical of allowing a vote on the First Step Act. So when those senators demanded minor tweaks to the bill, supporters complied — adding, among other changes, some restrictions to judges’ use of the “safety valve” and several more exclusions to earned time credits, including for some drug and violent offenders. The tweaks were enough to get the First Step Act through the finish line.

Another huge review of the research, released in 2017 by David Roodman of the Open Philanthropy Project, found that releasing people from prison earlier doesn’t lead to more crime, and that holding people in prison longer may actually increase crime.

Even the First Step Act’s most ardent supporters acknowledge that it will have a fairly small impact on the size of the federal prison system and particularly the national landscape. The law may let thousands of federal inmates out early, but, as Stanford drug policy expert Keith Humphreys noted in the Washington Post, more than 1,700 people are released from prison every day already — so the First Step Act in one sense only equates to adding a few more days of typical releases to the year.

While the federal government can incentivize states to adopt specific criminal justice policies, studies show that previous efforts, such as the 1994 federal crime law, had little to no impact. By and large, it seems local municipalities and states will only embrace federal incentives on criminal justice issues if they actually want to adopt the policies being encouraged.

Criminal justice reform, then, is going to fall largely to municipalities and states, and a law that might slightly cut incarceration on the federal level isn’t going to have a very big effect. (To this end, many cities and states are actually way ahead of the federal government when it comes to criminal justice reform, with many passing the kinds of sentencing reforms that the federal system has struggled to enact.)

That’s not to downplay the work of criminal justice reformers who are trying to reduce the size and burden of what amounts to a fairly large prison system at the federal level. But to understand the First Step Act, it’s important to put its full impact on mass incarceration in the broader national context.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62704719/1094199730.jpg.1545184116.jpg)

Congress changed all of that in the First Step Act. In expanding the number of people covered by the safety valve, Congress wrote that a defendant now must only show that he or she “does not have… (A) more than 4 criminal history points… (B) a prior 3-point offense… and (C) a prior 2-point violent offense.”

The “safety valve” was one of the only sensible things to come out of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the bill championed by then-Senator Joe Biden that, a quarter-century later, has been used to brand him a mass-incarcerating racist. The safety valve was intended to let people convicted of drug offenses as first-timers avoid the crushing mandatory minimum sentences that Congress had imposed on just about all drug dealing.

Eric Lopez got caught smuggling meth across the border. Everyone agreed he qualified for the safety valve except for his criminal history. Eric had one prior 3-point offense, and the government argued that was enough to disqualify him. Eric argued that the First Step Actamendment to the “safety valve” meant he had to have all three predicates: more than 4 points, one 3-point prior, and one 2-point prior violent offense.

Last week, the 9th Circuit agreed. In a decision that dramatically expands the reach of the safety valve, the Circuit applied the rules of statutory construction and held that the First Step amendment was unambiguous. “Put another way, we hold that ‘and’ means ‘and.’”

“We recognize that § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language might be viewed as a considerable departure from the prior version of § 3553(f)(1), which barred any defendant from safety-valve relief if he or she had more than one criminal-history point under the Sentencing Guidelines… As a result, § 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language could possibly result in more defendants receiving safety-valve relief than some in Congress anticipated… But sometimes Congress uses words that reach further than some members of Congress may have expected… We cannot ignore Congress’s plain and unambiguous language just because a statute might reach further than some in Congress expected… Section 3553(f)(1)’s plain and unambiguous language, the Senate’s own legislative drafting manual, § 3553(f)(1)’s structure as a conjunctive negative proof, and the canon of consistent usage result in only one plausible reading of § 3553(f)(1)’s“and” here: “And” is conjunctive. If Congress meant § 3553(f)(1)’s “and” to mean “or,” it has the authority to amend the statute accordingly. We do not.”

A little-known fact is that the US has only 5% of the world’s population, but 25% of the world’s inmates. The extremely high incarceration rate creates daily challenges all over the country, and our lawmakers are very aware that something needs to be done about it. In alignment with that, Congress passed the First Step Act in December 2018 as part of a larger federal prison reform plan. The First Step Act provides:

While this law affects only federal inmates (as opposed to those in state or county prisons), it sets a precedent for states to enact similar legislation to ease their own overcrowded and difficult prison situations.

Good conduct credits: Inmates who demonstrate ethical conduct and strict adherence to prison regulations are granted “good conduct credits” by the prison, each of which earns one day off their sentence. The maximum credits in federal prisons under the First Step Act are 54 in one year.

Halfway Houses (residential rehabilitation centers): Facilities that house low-risk inmates or those nearing the end of their sentences, allowing them limited freedom and extended participation in educational and job-seeking activities to help reintegrate them into society.

While many of the benefits provided by the First Step Act occur as a matter of course, such as reduced sentences, some benefits are discretionary – meaning you need to apply and get approved. Scenarios in which benefits may be requested include:

Petitioning for and receiving early release is best done with the help of a Los Angeles writs and appeals lawyer who has intimate and extensive knowledge of the First Step Act and other associated laws. At Werksman Jackson & Quinn LLP, our attorneys have decades of experience helping inmates accomplish an early release and improvements of their conditions, so contact us today.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

The First Step Act 2018 Bill Summary: On December 21, 2018, the President signed into law The First Step Act 2018, a bipartisan effort to reform the federal criminal justice system. The Law Office of Brandon Sample has assembled this detailed analysis of the First Step Act 2018 to help the public understand the ins and outs of the bill. If you are looking for a quick answer to your questions about the First Step Act, we suggest you revisit our prior articles.

We want to be crystal clear about our position: the First Step Act 2018 is not perfect by any stretch of the imagination. There will be thousands of inmates who are largely ineligible to benefit from many of the reforms contained in this law. But the legislation is, by its name, a FIRST STEP.

Since The First Step Act 2018 is broken out into six separate titles, we will break down the bill using that same organization. We are going to change it up and start from the end and work our way back towards Title I of the bill. If you would like to print a copy of this article for your loved one in prison, you may do so at this link: Law Office of Brandon Sample First Step Analysis.

The First Step Act works to address family separation caused by imprisonment. Under the Section 601 of the bill, the BOP will now be required to “place the prisoner in a facility as close as practicable to the prisoner’s primary residence,” and to the extent possible within 500 driving miles of the inmate’s home.

However, the First Step Act still provides some caveats to the “place inmates no further than 500 miles from home” rule. Placement of an inmate will still be subject to that inmate’s “security designation,” medical needs, bed availability and other security concerns of the BOP.

“Security designation,” is just a different way of saying whether an inmate is eligible to go to a medium security, low security, or high security prison based on factors

8613371530291

8613371530291