first step act and safety valve made in china

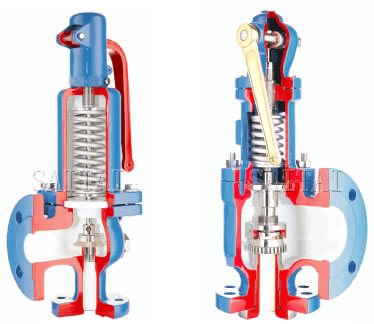

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

On behalf of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a coalition charged by its diverse membership of more than 220 national organizations to promote and protect civil and human rights in the United States, we write to express our support for the First Step Implementation Act of 2021 (S. 1014), the Prohibiting Punishment of Acquitted Conduct Act of 2021 (S. 601), and the COVID-19 Safer Detention Act of 2021 (S. 312). In total, these three bipartisan measures would bring about narrow, yet meaningful improvements to federal sentencing. While The Leadership Conference believes that further, and stronger, legislation is necessary to transform our nation’s untenable criminal-legal system, these bills are a welcome step in that direction. We urge you to support these bills and to oppose any amendments that substantially change these provisions.

The First Step Implementation Act of 2021 furthers the goals of the First Step Act of 2018 (FSA),[1] which markedly changed sentencing laws and curbed the number of individuals entering prison. Sentencing practices, such as federal mandatory minimum sentences, are the fundamental building blocks of our system’s use of unnecessarily harsh prison sentences that have fueled our crisis of mass incarceration. While the FSA made necessary advancements to the federal sentencing scheme, it represents only modest improvements to our system and did not implement retroactively key provisions — a necessary component of any federal sentencing legislation.

Accordingly, the First Step Implementation Act of 2021 corrects implementation and interpretation errors that contravene the spirit of the FSA — such as implementing retroactively key sentencing reforms. For instance, the legislation would make the FSA’s sentencing reforms retroactive to individuals who received enhanced mandatory minimum sentences for prior drug offenses and to individuals who received “stacked” mandatory minimum sentences; permit judges to expand the sentencing safety valve in federal drug cases if the court finds that the defendant’s criminal history score overrepresents their record’s seriousness or likelihood of recidivism; allow courts to reduce sentences for offenses committed by those under the age of 18 if the defendant has served at least 20 years; enable sealing or expungement of nonviolent juvenile delinquency adjudications and juvenile criminal records; and require the attorney general to establish procedures to ensure criminal records exchanged for employment purposes are accurate.

While we support the First Step Implementation Act, we also ask you to address other issues arising from the FSA through other mechanisms. In particular, we urge you to continue robust oversight over and investigations into the Bureau of Prisons’ (BOP) implementation of the use of the “Prisoner Assessment Tool Targeting Estimated Risk and Needs” (PATTERN). BOP continues to use PATTERN to make release decisions, even though experts have cautioned that it is scientifically unverified and built on historically biased data resulting in bias against Black people, Latino people, poor people, unhoused people, and people with mental illness.[2] In fact, a January 2021 report by the National Institute of Justice reveals that the Department of Justice was unable to revalidate PATTERN due to errors and inconsistencies — meaning the BOP is using an unvalidated risk-assessment tool to make life and death decisions during the global pandemic.[3] We urge the you to address this issue in several ways: by continuing vigorous and robust oversight to ensure BOP is meeting its commitments under the FSA, by advising BOP to halt the use of PATTERN until it is validated, and by introducing legislation to fix this unreliable and discriminatory assessment.

The Prohibiting Punishment of Acquitted Conduct Act of 2021 similarly makes meaningful improvements to sentencing laws. In particular, S. 601 would ensure that federal judges cannot consider acquitted or dismissed charges in their sentencing decisions. S. 601 would amend 18 U.S.C. §3661 to preclude federal courts from considering acquitted conduct at sentencing, except for the purposes of mitigating a sentence. While juries must convict based on the higher standard of “beyond a reasonable doubt,” current federal law permits judges to impose enhanced sentencing based on acquitted or dismissed charges under the less demanding standard of “preponderance of the evidence.” The consideration of such conduct in sentencing decisions compounds the trial penalty and can often lead to longer federal sentences, exacerbating mass incarceration and depriving defendants of basic due process. This legislation would correct an unjust facet of federal sentencing laws.

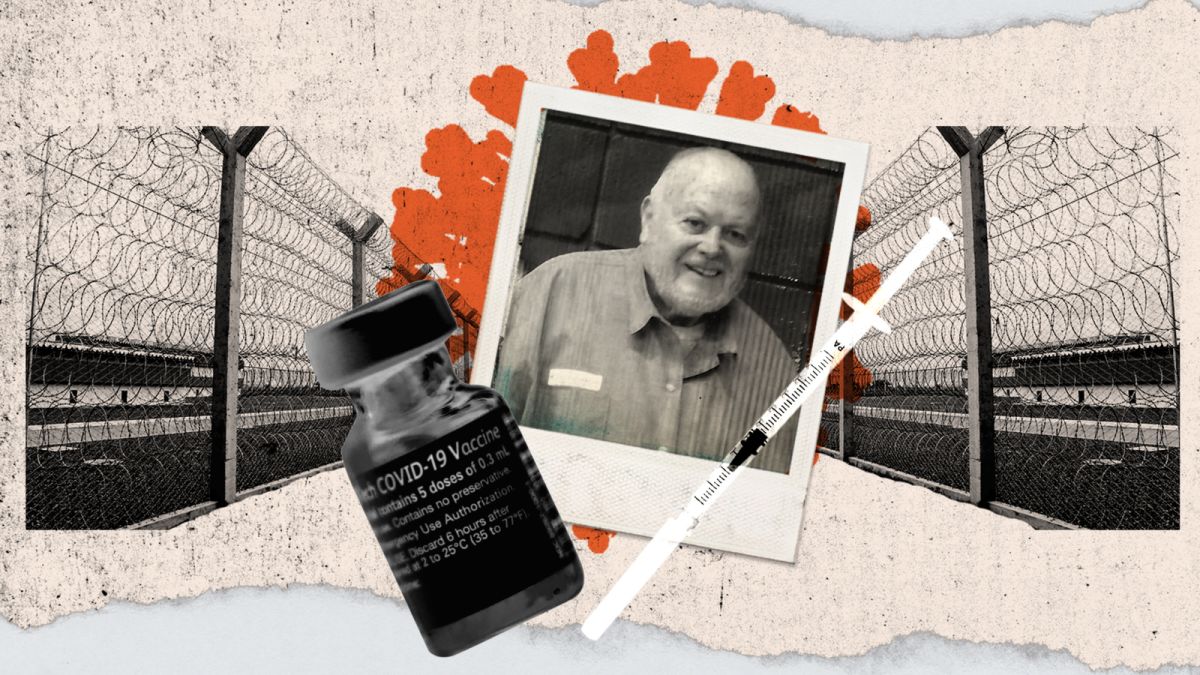

The COVID-19 Safer Detention Act of 2021 (S. 312) clarifies and expands the eligibility for the Elderly Home Detention Pilot Program introduced within the FSA. S. 312 ensures that eligibility decisions for the program are subject to judicial review and explicitly names COVID-19 vulnerability as a basis for compassionate release. S. 312 also shortens the judicial review waiting period for elderly home detention and compassionate release during the pandemic from 30 to 10 days. The COVID-19 virus has swept through federal prisons: as of September 10, 2021, more than 42,000 federally incarcerated individuals have contracted the coronavirus, and more than 250 federally incarcerated individuals, many of whom were over 60 years old, have died of the virus.[4] High rates of underlying health issues among incarcerated populations place many individuals in custody in high-risk categories that make them more susceptible to complications if they contract the virus.[5] This legislation provides for meaningful expansion of the pilot program and removes arbitrary benchmarks that ultimately endanger lives. Moreover, while this legislation is written within the context of the global health crisis, the pandemic has shown that release has not had a deleterious impact on public safety, and we encourage Congress to make permanent effective programs such as this even after the end of the pandemic.

These three bills represent meaningful improvements to address faults in the federal sentencing scheme and further fulfill the promise of the First Step Act. These bills will immediately save lives and curb the number of individuals forced into the criminal-legal system. We urge you to support these important bills. If you have any questions, please contact Sakira Cook, Senior Director of the Justice Reform Program, at [email protected].

[2] See Letter from the Leadership Conference for Civil and Human Rights to Attorney General Barr RE: The use of the PATTERN risk assessment in prioritizing release in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, available at https://civilrights.org/resource/letter-to-attorney-general-barr-re-the-use-of-the-pattern-risk-assessment-in-prioritizing-release-in-response-to-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

[3] Nat’l Inst. Of Justice. “2020 Review and Revalidation of the First Step Act Risk Assessment Tool.” Jan. 2021. Pg. 7. https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/256084.pdf.

[5] U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. “Special Report: Medical Problems of State and Federal Prisoners and Jail Inmates 2011-12.” Oct. 4, 2016. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mpsfpji1112.pdf

The Act represents a dramatically different and enlightened approach to fighting crime that is focused on rehabilitation, reintegration, and sentencing reduction, rather than the tough-on-crime, lock-them-up rhetoric of the past.

Perhaps the Act’s most far-reaching change to sentencing law is its expansion of the application of the Safety Valve—the provision of law that reduces a defendant’s offense level by two and allows judges to disregard an otherwise applicable mandatory minimum penalty if the defendant meets certain criteria. It is aimed at providing qualifying low-level, non-violent drug offenders a means of avoiding an otherwise draconian penalty. In fiscal year 2017, nearly one-third of all drug offenders were found eligible for the Safety Valve.

Until the Act, one of the criteria for the Safety Valve was that a defendant could not have more than a single criminal history point. This generally meant that a defendant with as little as a single prior misdemeanor conviction that resulted in a sentence of more than 60 days was precluded from receiving the Safety Valve.

Section 402 of the Act relaxes the criminal history point criterion to allow a defendant to have up to four criminal history points and still be eligible for the Safety Valve (provided all other criteria are met). Now, even a prior felony conviction would not per se render a defendant ineligible from receiving the Safety Valve so long as the prior felony did not result in a sentence of more than 13 months’ imprisonment.

Importantly, for purposes of the Safety Valve, prior sentences of 60 days or less, which generally result in one criminal history point, are never counted. However, any prior sentences of more than 13 months, or more than 60 days in the case of a violent offense, precludes application of the Safety Valve regardless of whether the criminal history points exceed four.

These changes to the Safety Valve criteria are not retroactive in any way, and only apply to convictions entered on or after the enactment of the Act. Despite this, it still is estimated that these changes to the Safety Valve will impact over 2,000 offenders annually.

Currently, defendants convicted of certain drug felonies are subject to a mandatory minimum 20 years’ imprisonment if they previously were convicted of a single drug felony. If they have two or more prior drug felonies, then the mandatory minimum becomes life imprisonment. Section 401 of the Act reduces these mandatory minimums to 15 years and 25 years respectively.

Section 401 expands the prior predicates to include serious violent felonies but limits any predicate offenses to either serious drug felonies or serious violent felonies. Furthermore, to qualify as a predicate, the defendant must have received more than 12 months’ imprisonment, and, with respect to drug offenses only, the sentence must have ended within 15 years of the commencement of the instant offense.

These amendments apply to any pending cases, except if sentencing already has occurred. Thus, they are not fully retroactive. Had they been made fully retroactive, it is estimated they would have reduced the sentences of just over 3,000 inmates. As it stands, these reduced mandatory minima are estimated to impact only 56 offenders annually.

Section 403 of the Act eliminates the so-called “stacking” of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A) penalties. Section 924(c) provides for various mandatory consecutive penalties for the possession, use, or discharge of a firearm during the commission of a felony violent or drug offense. However, for a “second or subsequent conviction” of 924(c), the mandatory consecutive penalty increases to 25 years.

Occasionally, the Government charges a defendant with multiple counts of 924(c), which results in each count being sentenced consecutive to each other as well as to the underlying predicate offense. For example, a defendant is charged with two counts of drug trafficking and two counts of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A)(i), which requires a consecutive 5 years’ imprisonment to the underlying offense for mere possession of a firearm during the commission of the drug offense. At sentencing, the Court imposes 40 months for the drug trafficking offenses. As a result of the first § 924(c)(1)(A)(i) conviction, the Court must impose a consecutive 60 months (5 years). But what about the second § 924(c)(1)(A)(i) conviction? In such situations, courts have been treating the second count as a “second or subsequent conviction.” As such, the 60-month consecutive sentence becomes a 300 month (25 years) consecutive sentence. In our hypothetical, then, the sentencing court would impose a total sentence of 400 months (40+60+300) inasmuch as the second 924(c) count was a “second or subsequent conviction.”

Now, under the Act, to avoid such an absurd and draconian result, Congress has clarified that the 25-year mandatory consecutive penalty only applies “after a prior conviction under this subsection has become final.” Thus, the enhanced mandatory consecutive penalty no longer can be applied to multiple counts of 924(c) violations.

Finally, Section 404 of the Act makes the changes brought about by the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 fully retroactive. As the U.S. Sentencing Commission’s “2015 Report to Congress: Impact of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010,” explained: “The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (FSA), enacted August 3, 2010, reduced the statutory penalties for crack cocaine offenses to produce an 18-to-1 crack-to-powder drug quantity ratio. The FSA eliminated the mandatory minimum sentence for simple possession of crack cocaine and increased statutory fines. It also directed the Commission to amend the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines to account for specified aggravating and mitigating circumstances in drug trafficking offenses involving any drug type.”

While the Act now makes the FSA fully retroactive, those prisoners who already have sought a reduction under the FSA and either received one, or their application was otherwise adjudicated on the merits, are not eligible for a second bite at the apple. It is estimated that full retroactive application of the FSA will impact 2,660 offenders.

Reducing the severity and frequency of some draconian mandatory minimum penalties, increasing the applicability of the safety valve, and giving full retroactive effect to the FSA signals a more sane approach to sentencing, which will help address prison overpopulation, while ensuring scarce prison space is reserved only for the more dangerous offenders.

Alan Ellis, a past President of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers and Fulbright Award winner, is a criminal defense lawyer with offices in San Francisco and New York. A nationally recognized authority in the fields of federal plea bargaining, sentencing, prison matters, appeals, and Section 2255 motions, he can be reached at AELaw1@alanellis.com.

Mark H. Allenbaugh, co-founder of Sentencing Stats, LLC, is a nationally recognized expert on federal sentencing, law, policy, and practice. A former staff attorney for the U.S. Sentencing Commission, he is a co-editor of Sentencing, Sanctions, and Corrections: Federal and State Law, Policy, and Practice (2nd ed., Foundation Press, 2002). He can be reached at mark@sentencingstats.com.

Today’s endorsement of federal criminal justice reform legislation by President Trump is a modern-day “Nixon goes to China” moment. In fact, his tough rhetoric – from speaking out against “American carnage” to favoring the execution of drug dealers – just might have made him the best person to deliver reform of our harsh and counterproductive federal sentencing laws. With his support, the bipartisan compromise should pass quickly and overwhelmingly.

Politics aside, the compromise bill President Trump endorsed today will keep more families together, strengthen communities, and keep crime low. The bipartisan bill reforms some of the most punitive and unjust mandatory minimum sentencing laws and invests in proven rehabilitative programs.

FAMM endorses this smart approach. We realize that 94 percent of all prisoners are going to come home one day, and we should do everything we can to help them become productive, law-abiding members of our communities.

In May, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the FIRST STEP Act as a prison reform bill with no sentencing reforms included. Senate leaders recently introduced a new version of the bill, which includes four important sentencing reform provisions. These reforms would impact only federal, not state, sentencing laws. The Senate must now pass its updated version and send it back to the House of Representatives for approval before the president can sign the bill into law.

Earlier this month, FAMM launched the #WeNeed60 Campaign, aimed at garnering the 60 Senate votes needed to pass the FIRST STEP Act. Sen. Mitch McConnell said earlier this month that he would bring the bill to the floor for a vote if his whip count ensures the support of 60 senators. The #WeNeed60 campaign encourages affected families, former prisoners, and the public to press their senators to commit to voting in favor of the FIRST STEP Act. Thousands of families flooded the phone lines of congressional leaders urging the bill’s passing.

For the original House version of the bill, which contained only prison reform, FAMM pushed to include a number of provisions. These are outlined in the FAMM report “Using Time to Reduce Crime: Federal Prisoner Survey Results Show Ways to Reduce Recidivism,” including good-time credit, compassionate release reform, and the 500-mile rule.

FAMM then spearheaded a group letter signed by 40 formerly incarcerated criminal justice reform advocates, urging the Senate to pass the FIRST STEP Act.

In July, FAMM held a lobby day and rally at the nation’s capital. Hundreds of families and advocates spoke with their lawmakers about the importance of passing the FIRST STEP Act.

For nearly three decades, FAMM has united the voices of affected families, the formerly incarcerated, and a range of stakeholders and advocates to fight for a more fair and effective justice system. FAMM’s focus on ending a one-size-fits-all punishment structure has led to reforms to sentencing and prison policies in 6 states and is paving the way to programs that support rehabilitation for the 94% of all prisoners who will return to our neighborhoods one day.

is a national nonpartisan advocacy organization that promotes fair and effective criminal justice policies that safeguard taxpayer dollars and keep our communities safe. Founded in 1991, FAMM is helping transform America’s criminal justice system by uniting the voices of impacted families and individuals and elevating the issues all across the country.

Editor’s Note:Michael Cohen, the former personal attorney to former President Donald J. Trump, is a podcaster and vocal advocate for prison reform. E. Danya Perry, a former federal and state prosecutor, is a Trustee of the Vera Institute of Justice and a founding partner of Perry Guha LLP. Joshua Perry was General Counsel at the New Orleans Public Defenders and Special Counsel for Civil Rights to the Connecticut Attorney General. He is Of Counsel with Perry Guha, LLP. The views expressed in this commentary are their own. Read more opinion on CNN.

Thursday’s release of a new rule interpreting the act opened the door to community reintegration and family reunification for up to half of all the people in federal custody, according to data from the Department of Justice.

For a long time, under Donald Trump’s administration, the BOP seemed to slow-walk and even undercut the First Step Act’s reforms, resulting in a patchy and unjust application.

We know this personally. One of us (Danya Perry, along with the firm she co-founded, Perry Guha LLP) is a lawyer who took the BOP to court over its refusal to quickly and properly implement the First Step Act—and won. Another (Michael Cohen) was a federal inmate who took the BOP on by himself, making the same arguments that prevailed in Danya’s case—and lost.

The First Step Act passed with rare bipartisan supermajorities and was signed into law by then-President Donald Trump on December 21, 2018. It enacted a suite of modest but meaningful reforms to the federal criminal legal system, where more than 157,000 people are in post-conviction custody. The Act’s reforms ranged from retroactively lowering racially discriminatory sentences for certain qualifying crack cocaine convictions to expanding a “safety valve” that allows some people convicted of drug offenses to be sentenced below the mandatory minimum.

And, importantly, the act set up the “Time Credit” program, allowing people in custody who have been convicted of nonviolent offenses to earn up to 15 days of credit for every 30 days of participation in recidivism reduction programs or “productive activities” like prison jobs. Time credits don’t shorten your sentence, but they can make youeligible for earlier transfer to a halfway house, home confinement or supervised release. That’s a big deal. BOP data shows that about half of all people in federal custody—tens of thousands of people—are eligible to earn those credits and get an early start on reintegration and family reunification.

One problem was that the act never defined how much programming a person in custody must complete in order to earn a “day” of participation. And it wasn’t 100% clear about when the Time Credit program actually was to begin.

The act left those things to the BOP—part of the Department of Justice—to work out. And the BOP’s first draft of a rule—known in administrative law lingo as a “proposed rule”—released on November 25, 2020 in the waning days of the Trump administration, seemed to set people up to fail.

The proposed rule required people in custody to complete eight full hours of programming in a day in order to earn a day’s worth of credit—even though, as the act’s bipartisan authors pointed out in a public letter, “BOP programs do not run for eight hours per day.” And it refused to give credit for programming completed before January 15, 2022—even though untold numbers of people in custody worked countless hours in response to the act’s promise.

And we did push back. In Goodman v. Ortiz, Perry Guha represented a client, who had earned enough Time Credit for immediate release, but whom the BOP refused to transfer to a halfway house or home confinement. A federal judge in the district of New Jerseygranted the petition and ordered the BOP to follow the act and give the petitioner the credit that he’d earned, which resulted in his release to a halfway house. Michael, meanwhile, was held in a different jurisdiction. And when he applied for relief from a different federal court, he didn’t get it—despite having qualified in the same way as Goodman. Those are the kinds of unequal, arbitrary results you get when the law isn’t clear or evenly applied.

But that won’t happen going forward. The Biden administration final rule, released last week, fixed both of those problems with the Trump administration’s first draft. And now, as the DOJ announced, thousands of people in custody will be eligible for release—including some who will be released “immediately.”

Goodman v. Ortiz helped to establish that Congress, in passing the act, intended the BOP to move quickly to give out Time Credits. And the BOP admirably, listened to the court’s ruling, citing Goodman in explaining why its new rule would grant credits for programming completed from December 18, 2018 onwards.

That’s only fair: When the First Step Act passed, a lot of people in custody began working hard for Time Credits. They should be given what they had been promised and what they had earned. We can’t ask people to pay a debt to society while society refuses to make good on its promises to them.

The BOP also listened to the voices of directly-impacted people and to the act’s bipartisan authorsin allowing up to 15 days of credit for every 30 day period of program participation—no matter how many hours per day the program runs. Again, that’s only fair. People in custody don’t decide how many hours of programming the BOP offers and they shouldn’t be penalized for the BOP’s programming decisions.

Let’s be clear: There is still a lot of work to be done. There are strong indicationsthat the BOP isnot offering enough high-quality programs to help support people in prison, particularly during the pandemic.

While unquestionably impactful, the act was indeed only a “first step” towards broader changes that are desperately needed to reduce our cruel and counterproductive overreliance on incarceration. And even this welcome development does not erase the needless suffering of too many people, while the BOP pushed back against inmates seeking time credit and initially proposeda rule that cut against Congress’ intent.

But, after years of frustration, this is an unmistakable win for incarcerated people and their families, for advocates and for a country that is still struggling to be rehabilitated from its chronic addiction to incarceration.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Alexandra George "21 is a double major in philosophy and political science. She conducts research withthePaper Prisons Initiativeand is a 2020-21 Hackworth Fellow at theMarkkula Center for Applied Ethics. Views are her own.

As of 2019, there were over1.5 million peopleincarcerated in state and federal prisons and jails in the United States. What is more, much of this population israpidly aging. The number of individuals serving life sentences who were between 55 years old and 65 years oldincreased by over 150%between 1993 and 2015. Clearly, many inmates will soon reach the end of their lives in prison. However, prisons areill-equipped to provide adequate palliative care. This combined with dying while incarceratedviolates inmates’ human dignity.

One solution to the above problem iscompassionate release, which is a series of state and federal policies that release inmates from prison due to “extraordinary and compelling” circumstances, including terminal illness, debilitating illness, and family emergencies. Compassionate release policies were first enacted at the federal level in 1984 as a part of theSentencing Reform Act(SRA). Lawmakers intended for the SRA to betough on crime, which translated to practices including theelimination of parolefor all federal prisoners who committed a federal offense on or after November 1, 1987. Congress recognized that this would lead to unfair sentences, so Congress created “safety valves” that courts could use to prevent unjust sentences. Compassionate release is one suchsafety valve.

Despite this, compassionate release is rarely granted. Between 1990 and 2000, only0.01%of the federal prison population were granted compassionate release annually. In fairness, Congress attempted to fix some of the administrative problems barring people from receiving compassionate release with theFirst Step Act of 2018. And these reforms were somewhat successful. In 2017, the year prior to Congress passing the First Step Act,twenty-four petitionswere granted. In 2019, the year after Congress passed the First Step Act,145 petitionswere granted. Nevertheless, compassionate release is still clearly a woefully underutilized tool.

Seeing the statistics about the infrequency with which compassionate release was granted inspired me to write apaperabout the ethics of compassionate release as a Hackworth Fellow. A key part of this paper looks at what ancient philosophers from across the globe might say about the ethics of compassionate release. First,Mencius, an ancient Chinese philosopher, would argue that granting compassionate release is ethical because we must extend our compassion as a society to suffering inmates in order to cultivate our innately good nature. Second,Indian and Tibetan Buddhist philosophers such asNāgārjunaargued that prisoners should be treated humanely, and that “those prisoners who are physically weak, and therefore pose less danger to society, should be released early.” Third, granting compassionate release is also ethical using anAristotelian common good approachbecause denying compassionate release denies people their fair share, which in turn creates a worse society. Thus, the approaches of Mencius, Indian and Tibetan Buddhism, and an Aristotelian notion of the common good yield the same conclusion: we need to grant compassionate release more than we currently are.

We recognize that granting compassionate release is often the ethical choice, especially considering that49 states, the District of Columbia, and thefederal governmentall have compassionate release policies. Despite recognizing the ethics of compassionate release, we continue to allow administrative challenges at thestateandfederallevel to prevent us from doing what we know is right. This is all the more concerning considering that it seems that the administrative challenges barring individuals from receiving compassionate release aresimple to fixrelative to the many great policy challenges lawmakers face.

As Bryan Stevenson wrote inJust Mercy, “simply punishing the broken--walking away from them or hiding them from sight--only ensures that they remain broken and we do, too. There is no wholeness outside of reciprocal humanity” (290). We are currently faced with a choice: what type of society do we want to be? Do we want to continue to treat compassionate release as a token ethical act, or do we want to make real change? Change is within reach, so long as we recognize and act on the “extraordinary and compelling” nature of compassion and reciprocal humanity.

"I’m a senior with a double major in philosophy and political science, born and raised in Los Angeles. As an aspiring lawyer, I enjoy studying the law, particularly as it intersects with politics and philosophy. I’m a member of the University Honors Program, the Communications Chair on the Honors Advisory Council, and president of the SCU Harry Potter Club. My hobbies include reading, contemplating philosophy, playing ukulele, and spending time with friends and family. My favorite role model is Ruth Bader Ginsburg."

After many months of negotiations between a Republican-controlled U.S. Congress and the Trump Administration, on December 21, 2018, the First Step Act of 2018 (FSA) was signed into law by President Trump.[1] While this legislation was named the “First Step Act” to signal that it was the first attempt at incremental change to the federal criminal justice system, that name is actually a misnomer and ignores several successful reforms that preceded the legislation’s passage.[2] The FSA was actually the next step of many previous steps that have resulted in reforms far more significant to the federal criminal justice system.

The United States has the highest rate of incarceration of any country in the world, and federal spending on incarceration in 2012 was estimated at $81 billion.[3] In 2013, the cost of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) accounted for nearly one-third of the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) discretionary budget.[4] Federal incarceration has become one of our nation’s biggest expenditures, swallowing the budget of federal law enforcement.[5] It costs more than $36,000 per year to house just one federal inmate,[6] almost four times the average yearly cost of tuition at a public university.

Well before Jared Kushner, President Trump’s son-in-law, joined with some conservative and progressive organizations and became interested in federal criminal justice reform, there were many criminal justice, civil rights, human rights, and faith-based activists who successfully advocated for justice reform, including sentencing reform, on the federal level over the past fifteen years. Early supporters of the FSA did not think that President Trump or the Republican Congress would support changes to sentencing laws, and were satisfied with including what they considered prison reform provisions or “back end” changes to the criminal justice system.[7] In addition, former U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions, the DOJ, and several members of Congress opposed including sentencing reforms.[8]

During the first six months after the law was enacted, almost all of the people who have benefited from the law benefited from the sentencing provisions that early supporters and former Attorney General Sessions were willing to sacrifice. However, many criminal justice, civil rights, and faith advocates, as well as members of Congress understood that no true changes to the federal system could happen without addressing the unjust sentencing laws that have contributed to the mass incarceration crisis in this country.[9]

Moreover, advocates and allies on the Hill knew what policies were driving federal incarceration and they were not the prison reform provisions in the FSA. Currently, forty-five percent of the people in federal prison are there for drug crimes. What was and is driving incarceration on the federal level are the long sentences associated with drug crimes and the increasing number of people being prosecuted for immigration crimes.[10] Thus, it is no surprise that the sentencing sections of the FSA, in the end, were the most important aspect of the bill, but were only added toward the end of the debate about federal reform.

The possibility of these efforts actually began under another Republican President, George W. Bush, who in his 2004 State of the Union speech said, “America is the land of second chance, and when the gates of the prison open, the path ahead should lead to a better life.”[11] This sentiment being expressed by a Republican President, a member of a party that has been known as the more “law and order” political party of the two major parties, created an opening to begin a conversation about criminal justice reform. Later that year, President Bush announced his Prisoner Re-Entry Initiative (PRI) designed to assist formerly incarcerated people in their efforts to return to their communities. PRI connected people returning from prison with faith-based and community organizations to assist them in finding work and prevent them from recidivating.[12] Ultimately, Congress passed legislation in 2008 called the Second Chance Act (SCA) that created funding for organizations around the country to help people coming home from prison by providing reentry services needed to transition back to their communities.[13] The concept for this federal funding was born out of President Bush’s PRI.

In 2005, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Brennan Center for Justice, and Break the Chains organizations published a groundbreaking report titled, Caught in the Net: The Impact of Drug Policies on Women and Families.[14] This report was one of the first publications to document the alarming rise of incarceration of women for drug offenses. In 2005, there were more than eight times as many women incarcerated in state and federal prisons and local jails as in 1980. The number of women imprisoned for drug-related crimes in state facilities increased by 888% between 1986 and 1999.[15] These numbers are important because more than forty-five percent of the people in federal prison are there for drug offenses, of which seven percent are women.

Almost simultaneously, federal advocates began to reinvigorate efforts to address one of the most notoriously discriminatory federal criminal laws, also known as the 100 to one crack to powder disparity. This law, enacted in 1986, punished people more harshly for selling crack cocaine than it did powder cocaine. Under the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, a person would receive at least a five-year mandatory minimum sentence for selling 500 grams of powder cocaine but would receive the same sentence for selling merely five grams of crack cocaine. More importantly, what was apparent at the time was that crack cocaine was used in African-American communities because it was more readily available due to the lower cost compared to powder cocaine. Powder cocaine was used more often by whites because they could afford to purchase the more expensive drug. In 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA 2010) which reduced the 100 to one disparity between crack and powder cocaine to eighteen to one and eliminated the five-year mandatory sentence for possession of crack cocaine.[16]

The recognition of the increasing number of women in federal prison has also been important to efforts to address the serious problems in the federal criminal justice system. The growing number of women in the system have been part of the catalyst for change. As of 2019, women make up more than seven percent (or more than 12,000)[17] of the BOP population compared to women consisting of 13,000 of the total state and federal prison population in 1980.[18] Since that time, the number of women in prison has increased by twice the rate of men incarcerated.[19] When women go to prison, their children and families are also symbolically incarcerated with them. Children are the collateral consequence of the increasing number of women in jails and prisons because their mother’s absence often leads to a breakdown of the family. Unfortunately, what often lands women in prison are their histories of physical and sexual abuse, high rates of HIV, and substance abuse problems.[20]

Between 2005 and 2019, a combination of legal, legislative, executive, and U.S. Sentencing Commission (Sentencing Commission) law and policy changes resulted in reforms that led to a decline in the federal prison population of more than 38,000 people.[21] At its height, the BOP held more than 219,000 people in federal prisons across the country. As of September 2019, those numbers have decreased to 177,251.[22] The reason for the significant decline is because these legal and policy changes were focused on revamping federal sentencing and retroactive application of changes. Similarly, the most impactful provision of the FSA has been retroactivity of the FSA 2010. The Sentencing Commission estimates that the expansion of the 1994 safety valve provision[23] will also have a significant effect for years to come.

Some of these reforms took place years before the “First Step” Act or bills that preceded it[24] were even thought of, but it is important to understand how these and other policy changes laid the foundation for a “First Step” Act to become law. Furthermore, early supporters of the “First Step” Act cannot rewrite history with the title of a bill. In the end, this legislation was an example of incremental change to the federal criminal justice system, but it was not the first example, nor the most significant. In order for history to reflect an accurate picture of how reforms to the federal criminal justice system have successfully unfolded over the past decade or more, this Article will detail the actual first steps that led to a political environment in Washington where criminal justice reform could be considered, and ultimately enacted in 2018.

Mandatory minimum penalties are criminal penalties requiring, upon conviction of a crime, the imposition of a specified minimum term of imprisonment.[25] The Boggs Act, which provided mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses, was passed in 1951.[26] In 1951, Congress began to enact additional mandatory minimum penalties for more federal crimes.[27] Congress passed the Narcotics Control Act in 1956, which increased these mandatory minimum sentences to five years for a first offense and ten years for each subsequent drug offense.[28]

Since then, mandatory minimum sentences have proliferated in every state and federal criminal code. In 1969, Nixon called for drastic changes to federal drug control laws. In 1970, Congress responded with the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, supported by both Republicans and Democrats, which eliminated all mandatory minimum drug sentences except for individuals who participated in large-scale ongoing drug operations. Nixon signed the Act on October 27, 1970.[29]

Ironically, the next year, Nixon declared a “war on drugs” and increased the presence of federal agencies charged with drug enforcement and supported bills with mandatory sentences.[30] John Ehrlichman, an aide to Nixon, more recently has admitted that the “war on drugs” was actually a war on black people:

You want to know what this was really all about. The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.[31]

Mandatory minimum sentences for federal drug offenses emerged again after the death of Len Bias. In 1986, University of Maryland basketball star Len Bias died of a drug overdose just days after the Boston Celtics picked him in the NBA draft.[32] After the reemergence of mandatory sentences in federal law in the 1980s, many observers began to see the same problems that lead to the repeal of drug mandatory minimums in 1970. Mandatory sentences prohibit judges from reducing an individual’s sentence based on mitigating factors such as circumstances of the case or a person’s role, motivation, or likelihood of repeating the crime. Treating similar defendants differently and different defendants the same is unfair. Also, it is ineffective at reducing criminal behavior because mandatory sentences do not take into account the many factors prosecutors consider when deciding if they will charge the minimum sentence.[33]

Mandatory minimum sentences take discretion away from judges and give it to prosecutors who use the threat of these lengthy sentences to frustrate individuals asserting their constitutional right to trial. The threat of long sentences, particularly at the federal level, puts immense pressure on people to plead guilty to crimes and waive their right to trial.[34] Only three percent of individuals charged with federal drug crimes go to trial.[35] Human Rights Watch believes this historically low rate of trials reflects an unbalanced and unhealthy criminal justice system.

Contrary to popular belief, mandatory minimum sentencing laws are neither mandatory nor do they impose minimum sentences. Some have said that the combination of unjust sentences and a dangerous combination of unencumbered prosecutorial power has created what is known as the “trial penalty.”[36] The trial penalty is when people who exercise their right to trial receive higher sentences than those who plead guilty. True mandatory sentencing laws would result in everyone arrested for the same crime receiving the same sentence if convicted. But in reality, mandatory sentences simply transfer the discretion that a judge should have to impose an individualized sentence based on relevant factors, such as a defendant’s role in the crime, criminal history, and likelihood of reoffending, and give that discretion to prosecutors.

Prosecutors have control over sentencing under mandatory sentencing laws because they have unreviewable authority to decide what charges to pursue. In prosecutors’ hands, the minimum transforms from a certain and severe sanction to a tool for prosecutors to incentivize behavior and make judgment calls. Often prosecutors use their charging power to cut deals, secure testimony against other individuals, and force guilty pleas in cases where the evidence is weak. They also have the authority to not charge people with mandatory sentences when they think that it would be too severe a sentence.

A prosecutor need never disclose her reasons for bringing or dropping a charge. Judges, on the other hand, must disclose their reasons for sentencing in the written public court record, and aggravating factors can be contested by the defendant.[37] A defendant faced with a plea deal of 1.5 years or a risk of twenty years imprisonment if he goes to trial is likely to choose the former, no matter how weak the evidence. Individuals who choose to exercise their constitutional rights and go to trial are often sentenced not only for their misconduct, but also for declining to take the plea deal on the prosecutor’s terms.[38] The threat of mandatory minimum penalties may cause defendants to give false information,[39] to plead guilty to charges of which they may actually be innocent,[40] or to forfeit a strong defense.[41]

Federal mandatory minimum laws and some state laws afford defendants relief from the mandatory minimum in exchange for information helpful to prosecutors. People charged with low-level crimes and charged with mandatory minimums—drug couriers, addicts, or those on the periphery of the drug trade, such as spouses—often have no information to give to prosecutors for a sentence reduction. Finally, it is extremely expensive to incarcerate people under mandatory sentences. By putting all discretion in the hands of prosecutors who have a professional interest in securing as many convictions as possible, mandatory minimums ensure that public policy concerns about cost, racial disparities, and whether a particular sentence results in public safety are not a priority.[42] The decision regarding what level of incarceration will serve public safety is best left in the hands of judges, who have more of an incentive to balance public safety needs against the facts of an individual case.

In the 1970s, observers of the American judicial system were increasingly concerned with the widespread disparity in sentencing. Judges, with very broad discretion, imposed widely varying sentences for the same offenses. The enactment of the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 (SRA)[43] was Congress’s response to the growing inequality in federal sentences.[44] The SRA’s objectives were to increase certainty and fairness in the federal sentencing system and to reduce unwarranted disparity among individuals with similar records who were found guilty of similar crimes. The legislation created the Sentencing Commission, an independent expert panel given the responsibilities of producing federal sentencing guidelines and monitoring the application of the guidelines.[45]

As enacted, the SRA codified a framework for a determinate sentencing scheme under federal law.[46] Supporters of the SRA wanted to reduce unwarranted disparity among defendants having similar records or guilty of similar conduct. They also wanted to increase certainty and fairness of sentencing. The drafter of the SRA, Kenneth Feinberg, said himself that the primary motivating factor was the concern over sentencing disparities.[47] Parole in the federal system was abolished entirely, and to provide the certainty and fairness that SRA proponents sought, sentences were to be based upon “articulate grounds.”[48] Courts were directed to “‘impose a sentence sufficient, but not greater than necessary, to comply with the purposes (of sentencing).’”[49] The statute enumerated four purposes of sentencing: (1) punishment, (2) deterrence, (3) incapacitation, and (4) rehabilitation.[50] However, the statutory text of the SRA provides no clear statement as to how these four purposes were to be reconciled with each other.

Not long after the passage of the SRA, Congress began to enact new mandatory minimum sentences.[51] From 1984 to 1990, Congress passed a number of mandatory minimums primarily aimed at drugs and violent crime.[52] Lawmakers argued that enacting mandatory penalties would deter crime by creating fixed and lengthy prison terms.[53] Less than ten years after passing many of the mandatory penalties, members of Congress familiar with criminal justice issues began to realize that these sentences were inconsistent with the objectives of the SRA.[54]

After the enactment of the SRA, the most infamous mandatory minimum law passed by Congress was the penalty relating to crack cocaine. Cocaine had long been illegal in America, and, as later happened with crack, powder cocaine’s prohibition had always carried a racial component.[55] Crack was a new method of packaging the drug, produced by heating a mixture of powder cocaine (cocaine hydrochloride), baking soda (sodium bicarbonate), and water. The chemical interaction between these ingredients creates what is commonly known as “crack”—a hard material similar to a rock.[56] Applying a hot flame will vaporize crack, and, through smoking, cocaine vapor can be inhaled into the lungs and can very quickly enter the bloodstream and go to the brain.

Between 1984 and 1985, crack began to appear in urban areas such as New York, Miami, and Los Angeles. The availability of small quantities of crack cocaine at an inexpensive price revolutionized inner-city drug markets.[57] By 1986, crack was widely available in large U.S. cities and was relatively inexpensive. For fifty dollars to $100, a person could buy powder cocaine in gram or half gram quantities. For five dollars to twenty dollars, however, a person could buy a small vial of crack that included a few crack rocks. Along with the new drug market that crack created in cities across America came dramatic claims about the effects of the drug.

In June 1986, the country was shocked by the death of University of Maryland basketball star Len Bias in the midst of crack cocaine’s emergence in the drug culture. Bias, who was African American, died of a drug and alcohol overdose three days after being drafted by the Boston Celtics. Many in the media and public assumed that Bias died of a crack overdose.[58] Motivated in large part by the notion that the infiltration of crack cocaine was devastating America’s inner cities and by Bias’ death, Congress quickly passed the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act (ADAA). Many in Congress believed that the existing sentences for drug crimes were inadequate to deal with the dangers of this new drug based on the enormous fear of crack. Although it was later revealed that Bias actually died of a powder cocaine overdose,[59] Congress had already passed the harsh, discriminatory crack cocaine law by the time the truth about Bias’ death was discovered.

Congress did not provide a clear record of the reasons for the sentencing disparity between minor crack infractions and serious powder offenses even though Congress intended to combat the crack cocaine “epidemic” through this legislation.[60] The Senate conducted only a single hearing on the 100 to one ratio, which only lasted a few hours and few hearings were held in the House on the enhanced penalties for crack offenses.[61] As a consequence of the ADAA’s expedited schedule, there was no committee report to document Congress’ intent in passing the ADAA or to analyze the legislation. The abbreviated legislative history of the ADAA does not provide a single consistently cited rationale for the crack powder penalty structure.

During consideration of an earlier version of the bill, the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Crime issued a report determining that the mandatory minimum sentencing framework would ensure that the DOJ directed its “most intense focus” on “major traffickers” and “serious traffickers.”[62] After consulting with Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) agents and prosecutors, the Subcommittee set the high penalties for major traffickers at a level of 100 grams of crack to 5000 grams of powder cocaine—a fifty to one disparity.[63] As the ADAA advanced through Congress, the Senate, citing the harmfulness of the drug, increased the penalty for crack.[64] The legislative history does not explain why Congress rejected or accepted any one ratio in particular beyond showing that different ratios were considered.[65]

What little legislative history that does exist suggests that members of Congress believed that crack was more addictive than powder cocaine[66] and that it caused crime.[67] It also indicates members of Congress thought that crack cocaine caused psychosis and death, and that young people were particularly prone to becoming addicted to it,[68] as well as that crack’s low cost and ease of manufacture would lead to even more widespread use. Based on what ultimately turned out to be myths, Congress decided to punish crack more severely than powder.

The rapid increase in the use of crack between 1984 and 1986 created many myths about the effects of the drug in popular culture. These myths were often used to justify treating crack cocaine differently from powder cocaine. For example, crack was thought to be so much more addictive than powder cocaine that it was “instantly” addictive. It was said to cause violent behavior, destroy the maternal instinct leading to the abandonment of children, be a unique danger to developing fetuses, and cause a generation of so-called “crack babies” that would plague the nation’s cities for their lifetimes. Such dramatic claims were widely repeated in the news media. As a result of the enormous fear of crack, many in Congress said that the existing sentences for drug violations were inadequate to deal with the dangers of this new drug. [69]

Two years later, drug-related crimes were still on the rise. In response, Congress intensified its war against crack cocaine by passing the Omnibus Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1988.[70] The 1988 Act created a five-year mandatory minimum and twenty-year maximum sentence for simple possession of five grams or more of crack cocaine.[71] The maximum penalty for simple possession of any amount of powder cocaine or any other drug remained at no more than one year in prison.

In the years after the enactment of the ADAA, many of the myths associated with crack cocaine have been dispelled. In 1996, a study published by the Journal of American Medical Association found that the physiological and psychoactive effects of cocaine are similar regardless of whether it is in the form of powder or crack.[72] In addition, the media stories that appeared in the late 1980s of crack-addicted mothers giving birth to “crack babies” are now considered greatly exaggerated.[73]

In the 1990s, federal sentencing policy for cocaine and crack offenses came under extensive scrutiny. These concerns led Congress in the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (1994 Crime Bill) to direct the Sentencing Commission to submit a report and recommendations to Congress on cocaine sentences.[74] On February 28, 1995, the Sentencing Commission unanimously recommended that changes be made to the cocaine sentencing structure including a reduction in the 100 to one ratio.[75] On May 1, 1995, the Sentencing Commission submitted to Congress proposed legislation and amendments to its sentencing guidelines, which would have equalized the penalties between crack and powder cocaine possession and distribution at the level of powder cocaine, and provided sentencing enhancements for violence or other harms.[76] On October 30, 1995, Congress rejected the proposed amendment to the sentencing guidelines and directed the Sentencing Commission to make further recommendations regarding the powder and crack cocaine statutes and guidelines that did not advocate parity.[77] For the first time in the guidelines’ history, Congress and the President rejected a guideline amendment approved by the Sentencing Commission.[78] Congress explicitly directed the Sentencing Commission that “the sentence imposed for trafficking in a quantity of crack cocaine should generally exceed the sentence imposed for trafficking in a like quantity of powder cocaine.”[79]

In response to this directive, in April 1997, the Sentencing Commission issued a second report again urging the elimination of the 100 to one ratio. The Sentencing Commission indicated that it was “firmly and unanimously in agreement that the current penalty differential for federal powder and crack cocaine cases should be reduced by changing the quantity levels that trigger mandatory minimum penalties for both powder and crack cocaine.”[80] Therefore, the Sentencing Commission recommended that Congress reduce the current 500-gram trigger for the five-year mandatory minimum sentence in powder cocaine offenses to a level between 125 and 375 grams and that it increase the five-gram trigger in crack cocaine offenses to between twenty-five and seventy-five grams.[81] The Clinton Administration also publicly supported reducing the ratio to ten to one.[82] Nevertheless, despite the Sentencing Commission’s recommendations, Congress made no changes to the sentencing structure.

Again in 2002, the Sentencing Commission examined the disparity. The Sentencing Commission had hearings with a wide range of experts, who overwhelmingly concluded that there is no valid scientific or medical distinction between powder and crack cocaine.[83] Among those experts was Dr. Glen Hanson, then Acting Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, who testified before the Sentencing Commission, stating that, in terms of pharmacological effects, crack cocaine is no more harmful than powder cocaine. Dr. Alfred Blumstein, Professor of Urban Systems and Operations Research at Carnegie Mellon University, indicated that it would be more rational to use sentencing enhancements to punish individuals who use violence, regardless of the drug type, rather than to base sentencing disparities on the chemical itself. Such enhancements should also account for a person’s role in the drug trade. He also noted that the 100 to one drug quantity disparity suggests racial discrimination.[84]

After the 2002 hearings, the Sentencing Commission issued a new report on crack and powder cocaine disparities and once again found that the 100 to one ratio between the drugs was unjustified.[85] The Sentencing Commission made the following findings: (1) the current penalties exaggerate the relative harmfulness of crack cocaine, (2) the current penalties sweep too broadly and apply most often to lower level offenders, (3) the current quantity-based penalties overstate the seriousness of most crack cocaine offenses and fail to provide adequate proportionality, and (4) the current penalties’ severity mostly impacts minorities.[86]

The Sentencing Commission recommended a three-pronged approach for revising the sentencing policy, based on their findings, which would: (1) increase the threshold quantity to trigger a five-year mandatory minimum for crack offenses to at least twenty-five grams and a ten year mandatory minimum for 250 grams (and repeal the mandatory minimum for simple possession of crack cocaine), (2) provide for sentencing enhancements, and (3) maintain the mandatory minimum thresholds for powder at their current levels.[87] Recommending a twenty to one ratio, the Sentencing Commission made clear that it again “firmly and unanimously” believed the ratio to be unjustified.[88]

Despite three commission reports and over twenty years of demonstrated evidence to the contrary, it took Congress until 2010 to address the crack cocaine disparity.

Federal judges for many years lamented over mandatory sentences including the nature of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines (Guidelines) that were created by the Sentencing Commission as a result of the SRA. Not only did federal judges protest the Guidelines, but several Supreme Court Justices also objected to the lack of discretion judges had as a result of mandatory sentences and the Guidelines. Former Associate Justice Anthony Kennedy declared: “I’m against mandatory sentences. They take away judicial discretion to serve the four goals of sentencing. American sentences are 8 times longer than their equivalents in Europe.”[89]

Stephen Breyer, a current Supreme Court Justice, stated that: “[i]n 1994 Congress enacted a ‘safety-valve’ permitting relief from mandatory minimums for certain non-violent, first-time drug offenders. This, in my view, is a small, tentative step in the right direction. A more complete solution would be to abolish mandatory minimums altogether.”[90]

[these] mandatory minimum sentences are perhaps a good example of the law of unintended consequences. There is a respectable body of opinion which believes that these mandatory minimums impose unduly harsh punishment for first-time offenders. . . . [M]andatory minimums have also led to an inordinate increase in the prison population and will require huge expenditures to build new prison space . . . .[91]

In 2004, the Blakely v. Washington[92] decision laid the groundwork for the Court to address mandatory federal sentencing guidelines. Blakely pleaded guilty to the kidnapping of his estranged wife which under Washington state law would have resulted in a maximum sentence of fifty-three months. The judge in the case sentenced Blakely to ninety months because he had acted with “deliberate cruelty.”[93] The Court held an “exceptional” sentence increase under state law, based on the judge’s finding and not a jury’s, violated his Sixth Amendment right to trial by jury.[94] The Court ruled that, based on its decision in Apprendi v. New Jersey,[95] facts increasing the penalty for a crime beyond the prescribed statutory maximum

8613371530291

8613371530291