first step act and safety valve price

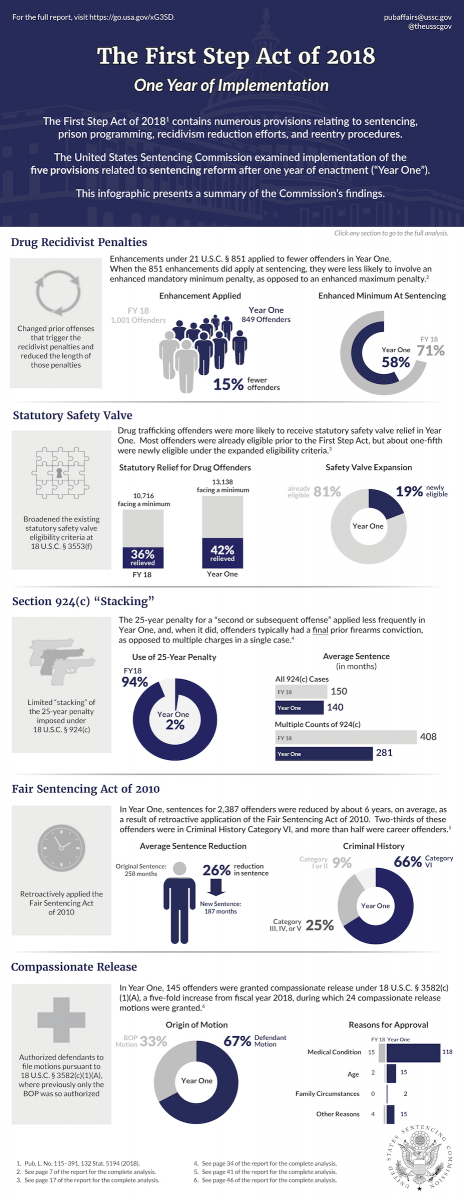

The Federal Safety Valve law permits a sentence in a drug conviction to go below the mandatory drug crime minimums for certain individuals that have a limited prior criminal history. This is a great benefit for those who want a second chance at life without sitting around incarcerated for many years. Prior to the First Step Act, if the defendant had more than one criminal history point, then they were ineligible for safety valve. The First Step Act changed this, now allowing for up to four prior criminal history points in certain circumstances.

The First Step Act now gives safety valve eligibility if: (1) the defendant does not have more than four prior criminal history points, excluding any points incurred from one point offenses; (2) a prior three point offense; and (3) a prior two point violent offense. This change drastically increased the amount of people who can minimize their mandatory sentence liability.

Understanding how safety valve works in light of the First Step Act is extremely important in how to incorporate these new laws into your case strategy. For example, given the increase in eligible defendants, it might be wise to do a plea if you have a favorable judge who will likely sentence to lesser time. Knowing these minute issues is very important and talking to a lawyer who is an experienced federal criminal defense attorney in southeast Michigan is what you should do. We are experienced federal criminal defense attorneys and would love to help you out. Contact us today.

More than a year after it was enacted in 2018, key parts of the law are working as promised, restoring a modicum of fairness to federal sentencing and helping to reduce the country’s unconscionably large federal prison population. But other parts are not, demonstrating the need for continued advocacy and more congressional oversight. The way the Justice Department has been handling prisoner releases during the coronavirus pandemic gives some insight into what’s going wrong.

President Trump has bragged about signing the law, which was the first criminal justice reform bill passed in nearly a decade. But simply signing it is not enough. He needs to see it through.

The First Step Act is the product of years of advocacy by people across the political spectrum. Indeed, a very similar bipartisan bill nearly passed in 2015, but was dragged down by election-year politics. The Trump administration began working on its own criminal justice bill in early 2018, and an initial deal was catalyzed by a core group of bipartisan legislators. It was then refined through a series of compromises and, once the Senate decided to pick up the bill, sailed through both houses of Congress with supermajority support.

The law we now know as the First Step Act accomplishes two discrete things, both aimed at making the federal justice system fairer and more focused on rehabilitation.

Its sentencing reformcomponents shorten federal prison sentences and give people additional chances to avoid mandatory minimum penalties by expanding a “safety valve” that allows a judge to impose a sentence lower than the statutory minimum in some cases. These parts of the First Step Act are almost automatic: once the act was signed, judges immediately began sentencing people to shorter prison terms in cases came before them. Similarly, people in federal prison for pre-2010 crack cocaine offenses immediately became eligible to apply for resentencing to a shorter prison term.

The law’s prison reformelements are designed to improve conditions in federal prison in two ways. One is by curbing inhumane practices, such as eliminating the use of restraints on pregnant women and encouraging placing people in prisons that are closer to their families. The other is by reorienting prisons around rehabilitation rather than punishment. That is no small task. Successfully expanding rehabilitative programming in federal prison will require significant follow-through from Congress and the Department of Justice. It’s no surprise, then, that these distinct parts of the act are functioning differently.

Before 2010, an offense involving 5 grams of crack cocaine, a form of the drug more common in the Black community, was punished as severely as one involving 500grams of powder. The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 changed that, reducing this 100:1 disparity to 18:1 — but only on a forward-going basis. People convicted under the now-outdated crack laws were stuck serving the very sentences that Congress had just repudiated.

The First Step Act fixed that by making the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive. According to the Justice Department, as of May, roughly 3,000 people serving outdated sentences for crack cocaine crimes had already been resentenced to shorter prison terms. Shortened or bypassed mandatory minimums mean that every year another estimated 2,000 people will receive prison sentences 20 percent shorter than they would have.

Another 3,100 people were released in July 2019, anywhere from a few days to a few months early, when the First Step Act’s “good time credit fix” went into effect. This simple change allowed people in federal prison to earn approximately an extra week off their sentence per year — and it applied retroactively, too. For some people it meant seeing their friends and family months earlier than expected.

Taken together, these changes represent an important decrease in incarceration. One year after the First Step Act was signed, the federal prison population was around 5,000 people smaller, continuing several years of declines. It has continued to shrink amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

To be sure, there’s still a long way to go: the federal prison population remains sky-high. And the Department of Justice does not appear to be in complete lockstep with the White House’s celebration of the law. In some old crack cocaine cases, federal prosecutors are opposing resentencing motions or seeking to reincarcerate people who have just been released. Prosecutors in these cases argue that any motions for resentencing must also consider the (often higher) amount of the drug the applicant possessed according to presentence reports. Other technical disputes are also cropping up, with the Department of Justice often arguing for a narrow interpretation of the First Step Act.

When it comes to improving programming within federal prison, even more work remains to be done. Federal prisons offer some opportunities for people in prison to participate in services that either address their individual needs, or help prepare them for life after release. Drug treatment and drug education are two examples; others include ESL and educational classes.

The First Step Act calls for the Bureau of Prisons to significantly expand these opportunities. Within a few years, the BOP must have “evidence-based recidivism reduction programs and productive activities” available for allpeople in prison. That means vocational training, educational classes, and behavioral therapy (to name a few options recommended in the act) should be staffed and broadly available. Participating in these programs will in turn enable imprisoned people to earn “time credits” that they can put toward a transfer to prerelease custody — that is, a halfway house or even home confinement — theoretically allowing them to finish their sentence outside of a prison.

Rolling out this system as intended will be a challenge, however, in part because BOP programs are already understaffed and underfunded. Around 25 percent of people spending more than a year in federal prison have completed zeroprograms. A recent BOP budget document described a lengthy waiting list for basic literacy programs. And according to the Federal Defenders of New York, the true extent of the BOP’s programming shortfall isn’t even known, because the BOP won’t share information on programming availability or capacity. The bureau offered little insight into its existing capacity and needs at a pair of congressional oversight hearings last fall. Worse, a recent report from the First Step Act’s Independent Review Committee, made up of outside experts to advise and assist the government with implementing the law, casts doubt on the quality of the BOP’s existing programming.

The BOP’s lack of transparency also makes it hard to know how “time credits” are being awarded — and thus, whether the BOP is permitting people to make progress toward prerelease custody as Congress intended. The First Step Act provides that most imprisoned people may earn 10 to 15 days of “time credits” for every 30 days of “successful participation” in recidivism-reduction programming. But a recent report suggests the BOP will award a specific number of “hours” for each program. How many “hours” make up a “day,” for the purpose of awarding credits? This highly technical issue may appear trivial, but could significantly affect the reach of the First Step Act.

People with inside knowledge of the system point to other concerns, too. The law excludes some imprisoned people from earning credits based on the crime that led to their incarceration or their role in the offense, and some advocates report that the BOP has applied those exclusions broadly, disqualifying a much larger part of the imprisoned population than Congress intended. Advocates also have heard that program availability in prisons is much spottier than the BOP has suggested, rendering illusory the DOJ’s claim that people are already being assigned to programs and “productive activities” tailored to their needs.

While some progress is being made, all of these concerns point to a need for more congressional oversight — narrowly focused on the availability and capacity of “recidivism reduction” programming in the BOP.

Any expansion of programming also won’t be free. Knowing that, the First Step Act authorized $75 million per year for five years for implementation. But authorization is only the beginning of the budgeting process. Congress must also formally appropriate money to the BOP to fund the First Step Act for each year that it is authorized.

Thankfully, in December 2019, Congress passed and the president signed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, which included full funding for the First Step Act through the end of the current fiscal year. That makes up for a bumpy start: last year, Congress failed to appropriate anything at all, forcing the DOJ to use $75 million from elsewhere in its budget to cover the temporary shortfall.

While this new funding is good news, it still might not be enough. According to a member of the Independent Review Committee, full implementation may cost closer to $300 million. After factoring in “training, staffing, [and] building things like classrooms,” he says, $75 million simply may not be enough. But any more substantial funding seems unlikely to materialize: in a recent budget, the White House sought nearly $300 million to fund improvements related to the law, of which only $23 million was earmarked for programming.

In late March, the Justice Department appeared to finally acknowledge the need to transfer people in federal prison to home confinement to keep them safe from the coronavirus. But transfers have been slow, and a recent report from ProPublica shows one reason why.

The DOJ prioritized transfers for people deemed to pose a “minimum” risk of recidivism under a new system developed for the First Step Act. But that system, called “PATTERN,” has never been perfect, and appears to have been quietly revised to make it more difficult to reach a “minimum” score — and by extension, that much harder to win a transfer to home confinement. This revelation offers the latest example of how the First Step Act’s implementation has proceeded in fits and starts.

Before imprisoned people can use “time credits” they’ve earned from prison programming, two conditions must be met. First, if they’re seeking a transfer to a halfway house, there must be a bed available. That’s not a sure thing, especially after a round of budget cuts by the Trump administration. Second, an incarcerated person must demonstrate that their risk of committing a new crime is low, as calculated by PATTERN.

The process of developing that tool has not gone smoothly. The first version unveiled by the DOJ, in July 2019, appeared to use a method for calculating “risk” that overstated the actual risk of re-offending among formerly incarcerated people, exaggerated racial disparities, and gave people only marginal credit for completing education, counseling, and other programs while in prison. Taken together, the tool gave short shrift to the idea that people can change while in prison — the very premise of the First Step Act.

Early this year, the DOJ shared what seemed like good news: PATTERN, it said, had been improved to partially address some of the concerns raised by the Brennan Center and others. But the tool continued to use an overly broad definition of recidivism. And while the DOJ claimed it introduced changes to reduce racial disparities, it did not release data on the revised tool’s actual effect on racial disparities. As a result, imprisoned people, families, lawyers, and advocates were all concerned when the DOJ announced it would use PATTERN to help determine who would be transferred out of federal prison during the pandemic.

Those concerns were justified. It now seems that the BOP changed PATTERN more significantly than they initially disclosed to make it much harder to qualify as a “low” or “minimum” risk. (A DOJ report, released a week after ProPublica’s story, suggests that the impact of these changes was relatively small, but offers limited data, and — still — provides no analysis of racial disparities.) This change will certainly narrow the effect of the First Step Act. But more urgently, it seems likely to keep more people in federal prison, exposed to a heightened risk of catching a deadly disease.

Trump has repeatedly claimed credit for passing the First Step Act. He did the same in a Super Bowl ad. Now his administration needs to do the hard work of ensuring that the law lives up to its promise.

A separate bipartisan bill, the First Step Act, S.3649, was introduced in the Senate on November 15. It includes an amended version of the recidivism reduction aspect of the bill, as well as a sentencing reform component. A

Executive Summary:The First Step Act aims to reduce recidivism by allowing low- or minimum-risk prisoners to earn time credits toward earlier transfer to prerelease custody such as a halfway house if they participate in certain recidivism-reducing programs while in prison. Prisoners guilty of some categories of offenses are automatically disqualified from this option. The bill also contains sentencing reforms that, among other things, reduce the enhanced mandatory minimum sentences for repeated drug-related offenses, while expanding the application of mandatory minimum sentences to include violent felons.

Requires the attorney general to review the Bureau of Prisons’ existing risk assessment system and develop a new system in consultation with a new Independent Review Committee. The new system will determine the recidivism risk of each new prisoner – minimum, low, medium, or high – assess the nature of their previous offenses, determine appropriate prison programming assignments, and determine when the prisoner can be transferred into prerelease custody or supervised release.

Requires that the new system also provide incentives and rewards such as increased phone and visitation privileges to prisoners who participate in recidivism-reducing programs.

Excludes prisoners from earning time credits if they are serving sentences for conviction of certain offenses, including: murder; terrorism; sexual exploitation of children; smuggling aliens into the U.S. with records of aggravated felonies; importing aliens for prostitution; assault of a law enforcement officer with a deadly weapon; domestic assault by a habitual offender; heroin or methamphetamine traffickers who are organizers, leaders, managers, and supervisors of the offense; and all fentanyl traffickers.

Requires the director of the BOP to ensure that every federal prison has a secure storage area for employees to store firearms and allow employees to carry concealed firearms on the premises of federal prisons outside of the secure perimeter.

Prohibits the use of restraints on pregnant prisoners in federal prisons. Exceptions are made in case of immediate flight risk; if the prisoner poses an immediate and serious threat of harm to herself or others; or if a health care professional determines restraints to be appropriate for the medical safety of the prisoner.

Reduces enhanced mandatory minimums for new cases involving prior drug felons. The three-strike mandatory penalty is reduced from life imprisonment to 25 years. The 20-year mandatory minimum for a second offense is reduced to 15 years.

Limits qualifying prior convictions to serious drug felonies occurring within 15 years and expands qualifying prior convictions to include serious violent felonies.

Broadens the “safety valve” allowing sentencing courts to consider a sentence below the statutory minimum for some non-violent, low-level drug offenders. Allows offenders to be considered under the safety valve with up to four criminal history points, excluding all one-point offenses, which are generally minor misdemeanors. Offenders with prior three-point felonies, which have sentences exceeding one year and one month, or two-point felonies, with sentences of 60 days or more, will not be eligible for the safety valve. Offenders must fully cooperate with law enforcement to be eligible for relief under the safety valve.

Clarifies that enhanced mandatory minimum sentences for use of a firearm during a crime of violence or a drug crime is limited to offenders who have been previously convicted and served a sentence for such an offense.

Allows prisoners to petition sentencing courts for a reduction in sentence consistent with the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced the disparity in sentencing between convictions involving crack and powder cocaine.

Directs BOP to place prisoners in facilities as close as practicable to their primary residence. Prohibits transferring higher-security designated prisoners to lower-security prisoners as a result of the bill.

Authorizes new markets for federal prison industries products and requires a GAO report on federal prison industries workplace conditions and products.

Restricts the use of juvenile solitary confinement for any reason other than as a temporary response to behavior that poses a serious and immediate risk of physical harm. Establishes maximum periods of solitary confinement for juveniles of three hours if they pose a serious and immediate risk of physical harm to others and 30 minutes if the juvenile only poses a risk to himself or herself.

CBO estimates the First Step Act would cost $352 million over 10 years, primarily as a result of former prisoners becoming eligible for federal programs such as Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security upon their release. However, CBO did not complete its estimate of the effect of the bill on spending subject to appropriation. CBO did score related

Over the years I have been retained by a few criminal defense clients after they had bad experience with a prior lawyer. The reasons for switching defense attorneys in midstream vary: sometimes it is concern over the lawyer’s competence, or concern that their case is not getting the attention it deserves, or even that they just don’t see eye to eye with their lawyer. One of the most common, and disturbing reasons though is that the client feels that their prior attorney ripped them off. These complaints generally involve “flat-fee” retainer agreements in which a lawyer and a client agree upon a fixed sum of money for the entire defense representation no matter whether it goes to trial or ends in a plea deal. I see cases all the time where a lawyer accepts a major felony case for a ridiculously low flat-fee just to land the client. Then, when it becomes obvious the case will require a lot of work, the attorney hits the client up for more money. I have even seen cases where the attorney threatens to withdraw from the case if the client does not come up with the additional funds. I call these “pump and dumps:” The lawyer pumps the client for a quick cash infusion and if the client balks, the lawyer tries to dump the client or the retainer agreement. When this happens, the client rightfully becomes upset and the situation quickly becomes untenable. What should a client do? They have (or should have) a written and enforceable fee agreement with the attorney. Then again, who wants a lawyer defending them from serious criminal charges when they claim they are being paid for their work? Defending clients charged with serious or complex felony cases in state and federal courts takes a great amount of work on the part of the criminal defense attorney, the client, and the defense team. These cases are expensive. To get an idea of how expensive, ask the attorney what their normal hourly fee is. The ask them how many hours they would expect to work in a case such as yours. What if it is a plea? What if it is a trial? If the lawyer’s retainer agreement sounds too good to be true, it probably is. The best thing a person can do when selecting a criminal defense attorney is to deal very clearly with this issue up-front. Hourly fee agreements will avoid the problem altogether. The attorney is paid only for the work performed. When negotiating an hourly fee agreement with a criminal defense attorney, be sure to ask the attorney to give a good faith estimate of the number of hours she or he thinks the case will consume depending on various outcomes like a plea agreement or a trial. If you are negotiating a flat-flee agreement make sure that both parties understand that regardless of how many hours the attorney must spend on the case, the fee agreement spells out the total amount to be paid in attorney fees. To protect both parties, flat fee agreements can be modified to suit the needs of each case. For example: The amount of the fee could be staggered to depend on at what stage of the proceedings the case is resolved: Pre-Indictment, with a plea agreement, after a trial etc. Regardless of the attorney and the fee structure you choose. I always recommend the potential client talk to as many knowledgeable and experienced criminal defense attorneys as the situation allows before settling on their pick. This will give the prospective client some idea of comparable fee agreements and rates. It will also allow both parties to get to know each other a little bit before signing up to work so closely together over so serious a matter. Switching attorneys in the middle of the case is sometimes unavoidable, but it is a situation best-avoided if possible.

In federal cases, Congress not only defines what is a crime that can cost the accused both freedom and property, but it also passes statutes that control how federal judges are allowed to sentence those who have been convicted of federal drug crimes. For instance, federal judges must follow the United States Sentencing Guidelines when sentencing someone upon conviction of a federal crime. For more on sentencing guidelines and how they work, read our discussion in Federal Sentencing Guidelines: Conspiracy To Distribute Controlled Substance Cases.

Sometimes, Congress sets a bottom line on the number of years someone must spend behind bars upon conviction for a specific federal crime. The federal judge in these situations has no discretion: he or she must follow the Congressional mandate.

These are called “mandatory minimums” in sentencing. They are commonly applied in federal drug cases in here Texas and elsewhere across the country. For more detail, read Mandatory Minimum Penalties in Federal Sentencing.

Of course, there are a tremendous number of federal laws that define federal drug crimes. For purposes of illustration, consider those federal drug crimes that come with either (1) a sentence of 10 years to life imprisonment or (2) those that come with a sentence of 5 to 40 years behind bars, both defined as the mandatory sentences to be given upon conviction for these defined federal drug crimes.

For reference, these refer to the statutory language of 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A) and 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B), which instruct the federal judge on how he or she shall sentence anyone convicted of the manufacture, distribution, or dispensing of a controlled substance (i.e., an illegal drug) or possession with intent to either of these things.

Key here: the judge is given the mandatory minimum number of years that the accused must spend behind bars by Congress via the federal statutory language. A federal judge cannot go below ten (10) years for a federal drug crime based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(A). He or she cannot go below five (5) years for a federal drug crime conviction based upon 21 U.S.C. §841(b)(1)(B).

How do you know if you are charged with one of these federal drug crimes that come with a mandatory minimum sentence of either 5-to-40 years (a “b1B” case) or 10-to-life (a “b1A” case)? Read the language of your Indictment. It will specify the statute’s citation. If you do not have a copy of your Indictment, please feel free to contact my office and we can provide you a copy.

Can’t there be any way to get around that set-in-stone bottom line? Yes. There is also a statutory exception which allows the federal judge to dip below that mandatory minimum number of years in some situations. It is called the “Safety Valve” defense.

Congress has passed another law that provides for an exception to the instructions given to federal judges on the mandatory minimum sentences that must be given according to Congressional mandate.

The law, 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f), provides for an exception that allows the federal judge some leeway in drug crime convictions where he or she would otherwise be required to follow the mandatory minimum sentencing statute. This is the Safety Value statute. It states as follows:

(f)Limitation on Applicability of Statutory Minimums in Certain Cases.—Notwithstanding anyother provision of law, in the case of an offense under section 401, 404, or 406 of theControlled Substances Act(21 U.S.C. 841, 844, 846), section 1010 or 1013 of theControlled Substances Import and Export Act(21 U.S.C. 960, 963), or section 70503 or 70506 of title 46, the court shall impose a sentence pursuant to guidelines promulgated by the United States Sentencing Commission undersection 994 of title 28without regard to any statutory minimum sentence, if the court finds at sentencing, after the Government has been afforded the opportunity to make a recommendation, that—

(4)the defendant was not an organizer, leader, manager, or supervisor of others in the offense, as determined under the sentencing guidelines and was not engaged in a continuing criminal enterprise, as defined in section 408 of theControlled Substances Act; and

(5)not later than the time of the sentencing hearing, the defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

The only way to allow for this exception to be applied in a federal sentencing hearing is for the defense to argue its application and to provide authenticated and admissible support for use of the Safety Valve.

How does the defense do this? It takes much more than referencing the exception to the general rule itself. The defense will have to demonstrate the convicted defendant meets the Safety Valve’s five (5) requirements.

Federal sentencing has its own reference manual that is used throughout the United States, called the United States Sentencing Guidelines (“USSG”). We have gone into detail about the USSG and its applications in earlier discussions; to learn more, read:

Essentially, the accused can be charged with a three-point offense; a two-point offense; or a one-point offense. The number of points will depend on things like if it is a violent crime; violent crimes get more points than non-violent ones. The higher the overall number of points, and the ultimate total score, then the longer the sentence to be given under the USSG.

For a successful safety valve defense, the defense has to show that the total Criminal History Points are four (4) or less. If you have a maximum of four Criminal History points, you have met the first criteria for the safety valve.

Note: prior to the passage of the First Step Act, things were much harsher. If the defense had even two Criminal History Points, then the accused was ineligible for the safety valve. The First Step Act increased the number of points, or score, from one to four as the maximum allowed for application of the safety valve. For more on the First Step Act, see The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 1 of 2 and The First Step Act and Texas Criminal Defense in 2019: Part 2 of 2.

Looking at the Safety Valve statute ( 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f)), the second step in achieving application of the safety valve defense involves the circumstances of the underlying criminal activity and whether or not it involved violence of threats or violence, or if the defendant possessed a firearm at the time.

It has been my experience that it is pretty common for there to be a firearm of some sort involved in a federal drug crime prosecution. Here, the impact of Texas being a part of the Fifth Judicial District for the United States Court of Appeals (“Fifth Circuit”) is important.

This is because this overseeing federal appeals court has looked at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) and its definition of possession of a firearm, and come to a different conclusion that the definition given in the USSG.

In the USSG, two points are given (“enhanced”) for possessing a firearm in furtherance of a federal drug trafficking offense. See, USSG §2D1.10, entitled Endangering Human Life While Illegally Manufacturing a Controlled Substance; Attempt or Conspiracy.

Meanwhile, the Fifth Circuit has ruled that under the Safety Valve Statute, the standard for the government is much higher. According to their ruling, in order to be disqualified from application of the safety valve because of possession of a firearm, the defendant has to have been actually in possession of the firearm or in construction possession of it. See, US v. Wilson, 105 F.3d 219 (5th Cir. 1997).

Consider how this works in a federal drug crime conspiracy case. Under the USSG, a defendant can receive two (2) points (“enhancement”) for possession of a firearm even if they never had their hands on the gun. As long as a co-conspirator (co-defendant) did have possession of it, and that possession was foreseeable by the defendant, then the Sentencing Guidelines allow for a harsher sentence (more points).

The position of the Fifth Circuit looks upon this situation and determines that it is one thing for the defendant to have possession of the firearm, and another for there to be stretching things to cover constructive possession when he or she never really had the gun.

This is the example of the importance of effective criminal defense representation, where research reveals that it is easier to achieve a safety valve defense with a reference to case law. The Fifth Circuit allows a situation where someone can get two (2) points under the USSG (“enhancement”) and still be eligible for the safety valve defense.

The commentary to § 5C1.2(2) provides that “[c]onsistent with [U.S.S.G.] § 1B1.3 (Relevant Conduct),” the use of the term “defendant” in § 5C1.2(2) “limits the accountability of the defendant to his own conduct and conduct that he aided or abetted, counseled, commanded, induced, procured, or willfully caused.” See U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2, comment. (n.4). This language mirrors § 1B1.3(a)(1)(A). Of import is the fact that this language omits the text of § 1B1.3(a)(1)(B) which provides that “relevant conduct” encompasses acts and omissions undertaken in a “jointly undertaken criminal activity,” e.g. a conspiracy.

Being bound by this commentary, we conclude that in determining a defendant’s eligibility for the safety valve, § 5C1.2(2) allows for consideration of only the defendant’s conduct, not the conduct of his co-conspirators. As it was Wilson’s co-conspirator, and not Wilson himself, who possessed the gun in the conspiracy,the district court erred in concluding that Wilson was ineligible to receive the benefit of § 5C1.2. Because application of § 5C1.2 is mandatory, see U.S.S.G. § 5C1.2 (providing that the court “shall” impose a sentencing without regard to the statutory minimum sentence if the defendant satisfies the provision’s criteria), we vacate Wilson’s sentence and remand for resentencing.

The defense must also be able to prove that the defendant’s role in the underlying criminal offense did not result in the death or bodily injury of someone else to achieve the safety valve defense under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f).

In drug cases, this can mean more than some type of violent scenario. The mere type of drug or controlled substance involved can impact the success of this defense. Sometimes, the drugs themselves are the type that can cause severe harm or death. Several controlled substances can be lethal. In a federal drug case, there is a special definition for death resulting from the distribution of a controlled substance.

If the defense can prove with authenticated and admissible evidence that the defendant did not distribute a drug or controlled substance that ended up with someone’s death, or severe bodily injury, then the safety valve defense will be available to them.

Role adjustments happen when someone is alleged to be involved in a conspiracy, and they act in some type of position of responsibility. They can be a leader, or organizer, or somebody who supervises other people in the operations, all as defined in the USSG.

If the defendant was deemed to meet one of these definitions, and had some kind of role involving responsibility or power in the illegal drug operations, then the USSG will add points (“enhance”) as a “role adjustment.”

If you are to achieve the safety valve defense, you cannot receive any “role adjustment” under the Sentencing Guidelines. This must be established to the court by your defense attorney at the sentencing.

Finally, under 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) the defense must show that the defendant has given a full and complete statement to the authorities. Specifically, the statute requires a showing that:

The defendant has truthfully provided to the Government all information and evidence the defendant has concerning the offense or offenses that were part of the same course of conduct or of a common scheme or plan, but the fact that the defendant has no relevant or useful other information to provide or that the Government is already aware of the information shall not preclude a determination by the court that the defendant has complied with this requirement.

I realize that for many people, this language brings with it the assumption that the defendant has to be a snitch in order to meet this requirement for the safety valve defense. This is not true.

With an experienced criminal defense lawyer, what it does mean is that the defendant has a meeting with the authorities with the goal of meeting the Safety Valve Statute requirements and no more.

The attorney can limit the scope of the meeting. He or she can make sure that law enforcement follows the rules for the meeting. The meeting is necessary for the defendant to achieve a safety valve defense, so there is no way to avoid a safety valve interview.

To get the sentence that is below the mandatory minimum sentence, the meeting is a must. However, it is not a free-for-all for the government where the defendant is ratting on other people.

I arranged for my client to have his safety valve meeting as well as establishing the other criteria needed for application of the Safety Valve statute. I was present at the meeting. There was no cooperation regarding the other defendants, and he did nothing more than the minimum to qualify for the defense. He was no snitch.

As a result, the safety valve was applied by the federal judge and my client achieved a safety valve application where he was sentenced to 8 years for distribution of meth: well below the 10 years of the mandatory minimums and the USSG calculation in his case of around 14 years.

Sadly, the same day that my client was sentenced, so were several of the co-conspirator defendants. I was aware that they were also eligible for the safety valve defense. However, the federal agent at the sentencing hearings that day told me that their lawyers never contact the government for a safety valve meeting.

They were never debriefed, so they could not meet the requirements for application of the safety value statute. The judge had no choice –they each had to be sentenced to the mandatory minimum sentences under the law.

On December 21, 2018, President Trump signed into law the First Step Act of 2018 (P.L. 115-391). The act was the culmination of several years of congressional debate about what Congress might do to reduce the size of the federal prison population while also creating mechanisms to maintain public safety.

Correctional and sentencing reform was an issue that drew interest from many Members of Congress. Some Members took it up for fiscal reasons; they were concerned that the increase in the Bureau of Prisons" (BOP) budget would take resources away from the Department of Justice"s (DOJ) other priorities. Other Members were interested in correctional reform due to concerns about the social consequences (e.g., the effects incarceration has on employment opportunities and the families of the incarcerated, or the normalizing of incarceration) of what some deem mass incarceration, or they wanted to roll back some of the tough on crime policy changes that Congress put in place during the 1980s and early 1990s.

This report provides an overview of the provisions of the First Step Act. The act has three major components: (1) correctional reform via the establishment of a risk and needs assessment system at BOP, (2) sentencing reform that involved changes to penalties for some federal offenses, and (3) the reauthorization of the Second Chance Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-199). The act also contains a series of other criminal justice-related provisions that include, for example, changes to the way good time credits are calculated for federal prisoners, prohibiting the use of restraints on pregnant inmates, expanding the market for products made by the Federal Prison Industries, and requiring BOP to aid prisoners with obtaining identification before they are released.

The correctional reform component of the First Step Act involves the development and implementation of a risk and needs assessment system (system) at BOP.

The act requires DOJ to develop the system to be used by BOP to assess the risk of recidivism of federal prisoners and assign prisoners to evidence-based recidivism reduction programsdetermine the risk of recidivism of each prisoner during the intake process and classify each prisoner as having a minimum, low, medium, or high risk;

determine the type and amount of recidivism reduction programming that is appropriate for each prisoner and assign each prisoner to programming based on the prisoner"s specific criminogenic needs;

reassign prisoners to appropriate recidivism reduction programs or productive activities based on their reassessed risk of recidivism to ensure that all prisoners have an opportunity to reduce their risk classification, that the programs address prisoners" criminogenic needs, and that all prisoners are able to successfully participate in such programs;

When developing the system, the Attorney General, with the assistance of the Independent Review Committee, is required toconduct a review of the existing risk and needs assessment systems;

conduct ongoing research and data analysis on (1) evidence-based recidivism reduction programs related to the use of risk and needs assessment, (2) the most effective and efficient uses of such programs, (3) which programs are the most effective at reducing recidivism, and the type, amount, and intensity of programming that most effectively reduces the risk of recidivism, and (4) products purchased by federal agencies that are manufactured overseas and could be manufactured by prisoners participating in a prison work program without reducing job opportunities for other workers in the United States;

annually review and validate the risk and needs assessment system, including an evaluation to ensure that assessments are based on dynamic risk factors (i.e., risk factors that can change); validate any tools that the system uses; and evaluate the recidivism rates among similarly classified prisoners to identify any unwarranted disparities, including disparities in such rates among similarly classified prisoners of different demographic groups, and make any changes to the system necessary to address any that are identified; and

direct BOP regarding (1) evidence-based recidivism reduction programs, (2) the ability for faith-based organizations to provide educational programs outside of religious courses, and (3) the addition of any new effective recidivism reduction programs that DOJ finds.

Under the act, the system is required to provide guidance on the type, amount, and intensity of recidivism reduction programming and productive activities to which each prisoner is assigned, including information on which programs prisoners should participate in based on their criminogenic needs and the ways that BOP can tailor programs to the specific criminogenic needs of each prisoner to reduce their risk of recidivism. The system is also required to provide guidance on how to group, to the extent practicable, prisoners with similar risk levels together in recidivism reduction programming and housing assignments.

The act requires BOP, when developing the system, to take steps to screen prisoners for dyslexia and to provide programs to treat prisoners who have it.

Within 180 days of DOJ releasing the system, BOP is required tocomplete the initial risk and needs assessment for each prisoner (including for prisoners who were incarcerated before the enactment of the First Step Act);

begin to expand the recidivism reduction programs and productive activities available at BOP facilities and add any new recidivism reduction programs and productive activities necessary to effectively implement the system; and

BOP is required to expand recidivism reduction programming and productive activities capacity so that all prisoners have an opportunity to participate in risk reduction programs within two years of BOP completing initial risk and needs assessments for all prisoners. During the two-year period when BOP is expanding recidivism reduction programs and productive activities, prisoners who are nearing their release date are given priority for placement in such programs.

BOP is required to provide all prisoners with the opportunity to participate in recidivism reduction programs that address their criminogenic needs or productive activities throughout their term of incarceration. High- and medium-risk prisoners are to have priority for placement in recidivism reduction programs, while the program focus for low-risk prisoners is on participation in productive activities.

Prisoners who successfully participate in recidivism reduction programming or productive activities are required to be reassessed not less than annually, and high- and medium-risk prisoners who have less than five years remaining until their projected release date are required to have more frequent reassessments. If the reassessment shows that a prisoner"s risk of recidivating or specific needs have changed, BOP is required to reassign the prisoner to recidivism reduction programs or productive activities consistent with those changes.

DOJ is required to develop and administer a training program for BOP employees on how to use the system. This training program must includeinitial training to educate employees on how to use the system in an appropriate and consistent manner,

To ensure that BOP is using the system in an appropriated and consistent manner, DOJ is required to monitor and assess how the system is used at BOP, including an annual audit of the system"s use.

The First Step Act requires the use of incentives and rewards for prisoners to participate in recidivism reduction programs, including the following:additional phone privileges, and if available, video conferencing privileges, of up to 30 minutes a day, and up to 510 minutes a month;

transfer to a facility closer to the prisoner"s release residence, subject to the availability of bedspace, the prisoner"s security designation, and the recommendation from the warden of the prison at which the prisoner is incarcerated at the time of making the request; and

additional incentives and rewards as determined by BOP, to include not less than two of the following: (1) increased commissary spending limits and product offerings, (2) greater email access, (3) consideration for transfer to preferred housing units; and (4) other incentives solicited from prisoners and determined appropriate by BOP.

Under the act, prisoners who successfully complete recidivism reduction programming are eligible to earn up to 10 days of time credits for every 30 days of program participation. Minimum and low-risk prisoners who successfully completed recidivism reduction or productive activities and whose assessed risk of recidivism has not increased over two consecutive assessments are eligible to earn up to an additional five days of time credits for every 30 days of successful participation. However, prisoners serving a sentence for a conviction of any one of multiple enumerated offenses are ineligible to earn additional time credits regardless of risk level, though these prisoners are eligible to earn the other incentives and rewards for program participation outlined above. Offenses that make prisoners ineligible to earn additional time credits can generally be categorized as violent, terrorism, espionage, human trafficking, sex and sexual exploitation, repeat felon in possession of firearm, certain fraud, or high-level drug offenses. Prisoners who are subject to a final order of removal under immigration law are ineligible for additional earned time credits provided by the First Step Act.

Prisoners cannot retroactively earn time credits for programs they completed prior to the enactment of the First Step Act, and they cannot earn time credits for programs completed while detained pending adjudication of their cases.

The act requires BOP to develop guidelines for reducing time credits prisoners earned under the system for violating institutional rules or the rules of recidivism reduction programs and productive activities. The guidelines must also include a description of a process for prisoners to earn back any time credits they lost due to misconduct.

the remainder of his/her imposed term of imprisonment has been computed under applicable law (e.g., any good time credits the prisoner has earned have been credited to his/her sentence); and

the prisoner has been determined to be a minimum or low risk to recidivate based on his/her last two assessments, or has had a petition to be transferred to prerelease custody approved by the warden, after the warden"s determination that the prisoner (1) would not be a danger to society if transferred to prerelease custody, (2) has made a good faith effort to lower his/her recidivism risk through participation in recidivism reduction programs or productive activities, and (3) is unlikely to recidivate.

A prisoner who is required to serve a period of supervised release after his/her term of incarceration and has earned time credits equivalent to the time remaining on his/her prison sentence can be transferred directly to supervised release if the prisoner"s latest reassessment shows that he/she is a minimum or low risk to recidivate.

Prisoners who are placed on prerelease custody on home confinement are subject to a series of conditions. Per the act, prisoners on home confinement are required to have 24-hour electronic monitoring that enables the identification of their location and the time, and must remain in their residences, except togo to work or participate in job-seeking activities,

When monitoring adherence to the conditions of prerelease custody, BOP is required, to the extent practicable, to reduce the restrictiveness of those conditions for prisoners who demonstrate continued compliance with their conditions.

If a prisoner violates the conditions of prerelease custody, BOP is authorized to place more conditions on the prisoner, or revoke prerelease custody and require the prisoner to serve the remainder of the sentence in prison. If the violation is nontechnical

Two years after the enactment of the First Step Act, and each year thereafter for the next five years, DOJ is required to submit a report to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees and the House and Senate Subcommittees on Commerce, Justice, Science, and Related Agencies (CJS) Appropriations that includes information onthe types and effectiveness of recidivism reduction programs and productive activities provided by BOP, including the capacity of each program and activity at each prison and any gaps or shortages in capacity of such programs and activities;

the recidivism rates of prisoners released from federal prison, based on the following criteria: (1) the primary offense of conviction; (2) the length of the sentence imposed and served; (3) the facility or facilities in which the prisoner"s sentence was served; (4) the type of recidivism reduction programming; (5) prisoners" assessed and reassessed risk of recidivism; and (6) the type of productive activities;

the status of prison work programs offered by BOP, including a strategy to expanding prison work opportunities for prisoners without reducing job opportunities for nonincarcerated U.S. workers; and

any budgetary savings that have resulted from the implementation of the act, and a strategy for investing those savings in other federal, state, and local law enforcement activities and expanding recidivism reduction programs and productive activities at BOP facilities.

Within two years of the enactment of the First Step Act, the Independent Review Committee is required to submit a report to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees and the House and Senate CJS Appropriations Subcommittees that includesa list of all offenses that make prisoners ineligible for earned time credits under the system, and the number of prisoners excluded for each offense by age, race, and sex;

the criminal history categories of prisoners ineligible to receive earned time credits under the system, and the number of prisoners excluded for each category by age, race, and sex;

the number of prisoners ineligible for earned time credits under the system who did not participate in recidivism reduction programming or productive activities by age, race, and sex; and

any recommendations for modifications to the list of offenses that make prisoners ineligible to earn time credits and any other recommendations regarding recidivism reduction.

Within two years of BOP implementing the system, and every two years thereafter, the Government Accountability Office is required to audit how the system is being used at BOP facilities. The audit must include an analysis of the following:whether prisoners are being assessed under the system with the required frequency;

whether BOP is offering the type, amount, and intensity of recidivism reduction programs and productive activities that allow prisoners to earn the maximum amount of additional time credits for which they are eligible;

The First Step Act authorizes $75 million per fiscal year from FY2019 to FY2023 for DOJ to establish and implement the system; 80% of this funding is to be directed to BOP for implementation.

The First Step Act makes several changes to federal sentencing law. The act reduced the mandatory minimum sentences for certain drug offenses, expanded the scope of the safety valve, eliminated the stacking provision, and made the provisions of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-220) retroactive.

The act adjusts the mandatory minimum sentences for certain drug traffickers with prior drug convictions. The act reduces the 20-year mandatory minimum (applicable where the offender has one prior qualifying conviction) to a 15-year mandatory minimum and reduces the life sentence mandatory minimum (applicable where the offender has two or more prior qualifying convictions) to a 25-year mandatory minimum.serious drug felonyserious violent felonyfelony drug offense.

The act makes drug offenders with minor criminal records eligible for the safety valve provision, which previously applied only to offenders with virtually spotless criminal records.

The act eliminates stacking by providing that the 25-year mandatory minimum for a "second or subsequent" conviction for use of a firearm in furtherance of a drug trafficking crime or a violent crime applies only where the offender has a prior conviction for use of a firearm that is already final.

The First Step Act authorizes courts to apply retroactively the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which increased the threshold quantities of crack cocaine sufficient to trigger mandatory minimum sentences, by resentencing qualified prisoners as if the Fair Sentencing Act had been in effect at the time of their offenses.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act of 2018 (Title V of the First Step Act) reauthorizes many of the grant programs that were initially authorized by the Second Chance Act of 2007 (P.L. 110-199). The Second Chance Reauthorization Act also reauthorized a BOP pilot program to provide early release to elderly prisoners.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amends the authorization for the Adult and Juvenile State and Local Offender Demonstration Program so grants can be awarded to states, local governments, territories, or Indian tribes, or any combination thereof, in partnership with interested persons (including federal correctional officials), service providers, and nonprofit organizations, for the strategic planning and implementation of reentry programs. The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amended the authorization for this program to allow grants to be used for reentry courts and promoting employment opportunities consistent with a transitional jobs strategy in addition to the purposes for which grants could already be awarded.

The act also amended the Second Chance Act authorizing legislation for the program to allow DOJ to award both planning and implementation grants. DOJ is required to develop a procedure to allow applicants to submit a single grant application when applying for both planning and implementation grants.

Under the amended program, DOJ is authorized to award up to $75,000 for planning grants and is prohibited from awarding more than $1 million in planning and implementation grants to any single entity. The program period for planning grants is limited to one year and implementation grants are limited to two years. DOJ is also required to make every effort to ensure the equitable geographic distribution of grants, taking into account the needs of underserved populations, including tribal and rural communities.

discussing the role of federal and state corrections, community corrections, juvenile justice systems, and tribal and local jail systems in ensuring the successful reentry of ex-offenders into the applicants" communities;

providing evidence of collaboration with state, local, and tribal agencies overseeing health, housing, child welfare, education, substance abuse, victim services, employment agencies, and local law enforcement agencies;

providing a plan for analyzing the barriers (e.g., statutory, regulatory, rules-based, or practice-based) to reentry for ex-offenders in the applicants" communities;

DOJ is also required to give priority consideration to applications for implementation grants that focus on areas with a disproportionate population of returning prisoners, received input from stakeholders and coordinated with prisoners families, demonstrate effective case assessment and management, review the process by which violation of community supervision are adjudicated, provide for an independent evaluation of reentry programs, target moderate and high-risk returning prisoners, and target returning prisoners with histories of homelessness, substance abuse, or mental illness.

Under the amended program, applicants for implementation grants would be required to develop a strategic reentry plan that contains measurable three-year performance outcomes. Applicants would be required to develop a feasible goal for reducing recidivism using baseline data collected through the partnership with the local evaluator. Applicants are required to use, to the extent practicable, random assignment and controlled studies, or rigorous quasi-experimental studies with matched comparison groups, to determine the effectiveness of the program.

As authorized by the Second Chance Act, grantees under the Adult and Juvenile State and Local Offender Demonstration program are required to submit annual reports to DOJ that identify the specific progress made toward achieving their strategic performance outcomes, which they are required to submit as a part of their reentry strategic plans. Data on performance measures only need to be submitted by grantees that receive an implementation grant. The act repeals some performance outcomes (i.e., increased housing opportunities, reduction in substance abuse, and increased participation in substance abuse and mental health services) and adds the following outcomes:increased number of staff trained to administer reentry services;

The act allows applicants for implementation grants to include a cost-benefit analysis as a performance measure under their required reentry strategic plan.

The Second Chance Act authorized DOJ to make grants to states, local governments, and Indian tribes to develop, implement, and expand the use of family-based substance abuse treatment programs as an alternative to incarceration for parents who were convicted of nonviolent drug offenses and to provide prison-based family treatment programs for incarcerated parents of minor children.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amends the authorization for the program to allow grants to be awarded to nonprofit organizations and requires DOJ to give priority consideration to nonprofit organizations that demonstrate a relationship with state and local criminal justice agencies, including the judiciary and prosecutorial agencies or local correctional agencies.

The Second Chance Act authorized a grant program to evaluate and improve academic and vocational education in prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities. This program authorizes DOJ to make grants to states, units of local government, territories, Indian tribes, and other public and private entities to identify and implement best practices related to the provision of academic and vocational education in prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities. Grantees are required to submit reports within 90 days of the end of the final fiscal year of a grant detailing the progress they have made, and to allow DOJ to evaluate improved academic and vocational education methods carried out with grants provided under this program.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amends the authorizing legislation for this program to require DOJ to identify and publish best practices relating to academic and vocational education for offenders in prisons, jails, and juvenile facilities. In identifying best practices, the evaluations conducted under this program must be considered.

The Second Chance Act authorized DOJ to make grants to states, units of local government, territories, and Indian tribes to provide technology career training for prisoners. Grants could be awarded for programs that establish technology careers training programs for inmates in a prison, jail, or juvenile detention facility.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act expanded the scope of the program to allow grant funds to be used to provide any career training to those who are soon to be released and during transition and reentry into the community. The act makes nonprofit organizations an eligible applicant under the program. Under the legislation, grants funds could be used to provide subsidized employment if it is a part of a career training program. The act also requires DOJ to give priority consideration to any application for a grant thatprovides an assessment of local demand for employees in the geographic area to which offenders are likely to return,

The Second Chance Act authorized DOJ to make grants to states, units of local governments, territories, and Indian tribes in order to improve drug treatment programs in prisons and reduce the post-prison use of alcohol and other drugs by long-term users under correctional supervision. Grants may be used to continue or improve existing drug treatment programs, develop and implement programs for long-term users, provide addiction recovery support services, or establish medication assisted treatment (MAT) services as part of any drug treatment program offered to prisoners.

The Second Chance Act authorized DOJ to make grants to nonprofit organizations and Indian tribes to provide mentoring and other transitional services for offenders being released into the community. Funds could be used for mentoring programs in prisons or jails and during reentry, programs providing transition services during reentry, and programs providing training for mentors on the criminal justice system and victims issues.

The Second Chance Reauthorization Act amends the authorization for the program to pivot the focus toward providing community-based transitional services to former inmates r

8613371530291

8613371530291