frontier safety valve quotation

“But today the frontier is closed, the safety valve shut. Whatever metaphor one wants to use, the country has lived past the end of its myth. Where the frontier symbolized perennial rebirth, a culture in springtime, those eight prototypes in Otay Mesa loom like tombstones. After centuries of fleeing forward across the blood meridian, all the things that expansion was supposed to preserve have been destroyed, and all the things it was meant to destroy have been preserved. Instead of peace, there’s endless war. Instead of a critical, resilient, and progressive citizenry, a conspiratorial nihilism, rejecting reason and dreading change, has taken hold. Factionalism congealed and won a national election.”

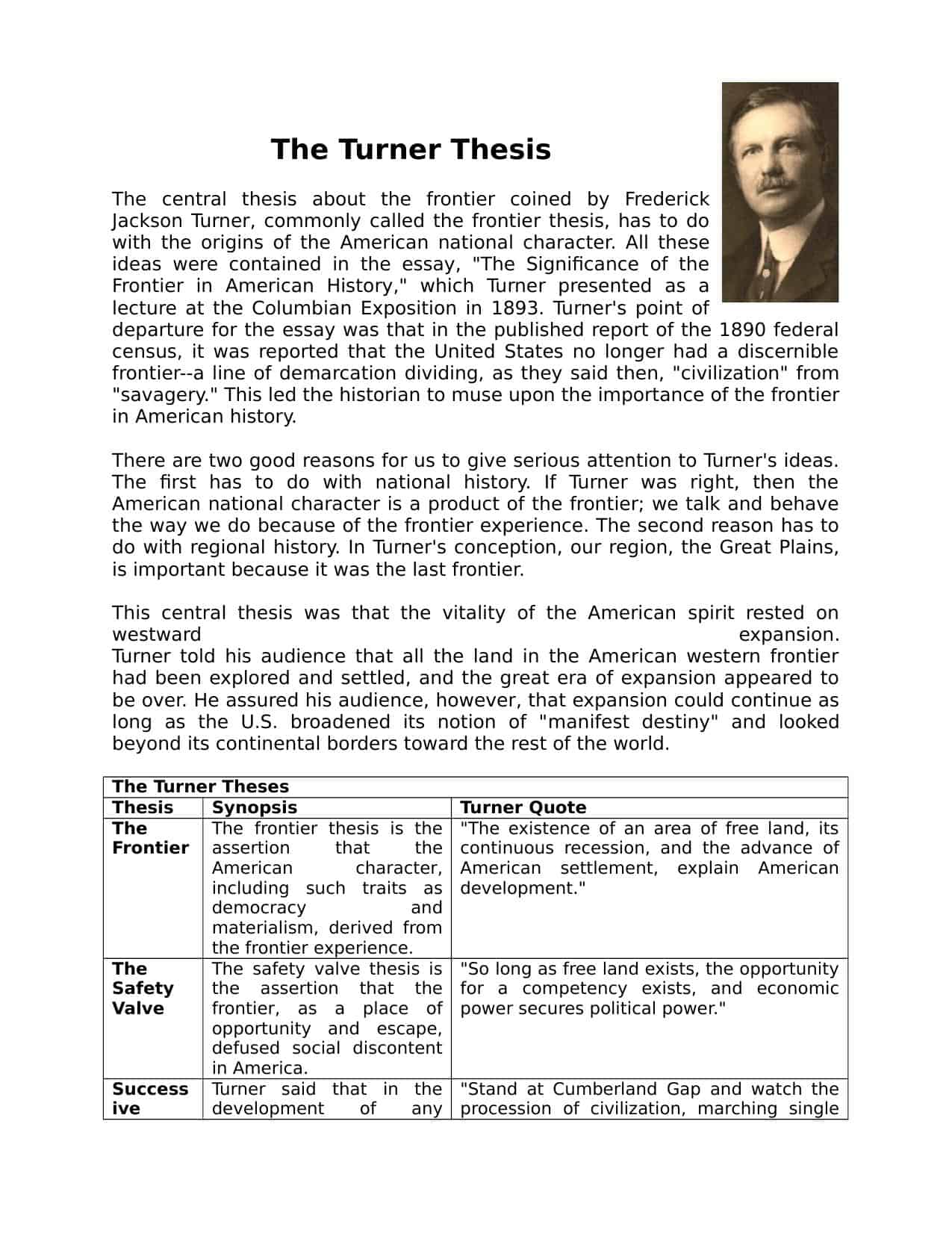

Woe to the AP U.S. History student who has never studied these words: “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.” That’s Frederick Jackson Turner’s highly influential “Frontier Thesis,” expounded in 1893, a favorite question on tests, and still of great interest to Greg Grandin as one of America’s most problematic guiding myths.

Turner suggested that our open frontier served as a benign safety valve. In “The End of the Myth,” Grandin observes that it instead allowed white Americans to push problems and problematic people (e.g. Native Americans) ever westward, over the Appalachians, past the Mississippi, over the Rockies and, on, eventually, to the Pacific. While Grandin spends most of his book examining the debates about and extensions of Turner’s notion, he offers a new thesis: that the frontier myth is now, in any case, dead, its prominence having been usurped by the mighty (and also misguided) myth of the Border Wall. One myth, of freedom and opportunity, is replaced by another, grim, notion: that of closure, and of whiteness that must be protected.

Grandin — a Yale historian whose previous books, including his Pulitzer Prize finalist “Fordlandia: The Rise and Fall of Henry Ford’s Forgotten Jungle City” (2009), have mostly featured Latin America — fortunately excels in both history and English. In “The End of the Myth,” for which he was awarded this year’s Pulitzer for nonfiction, he focuses on sociolinguistic analysis of our unruly national myths, those suggested by words such as “frontier,” “border,” “freedom” and “wall.” The book is a subtle but highly readable analysis of these metaphors in American thought and actions from Colonial days to this moment. Because it was published in 2019, it is pre-pandemic in scope — but it feels just as sad and timely as this morning’s death counts, both those from COVID-19 and those from racial injustice.

Like any good historian-poet, Grandin creates spiritual through-lines that pull his readers inexorably along the path of America’s westward expansion, making us take responsibility for bloody events we may never have learned about but certainly should have. And he finally sets us down, chastened, to hear this evening’s breaking news, featuring Donald Trump. Grandin suggests Trump has co-opted the Frontier but transmogrified it into the Wall. In Grandin’s words, “The frontier was, ultimately, a mirage, an ideological relic of a now-exhausted universalism. … All could benefit; all could rise and share in the earth’s riches. The wall, in contrast, is a monument to disenchantment, to a kind of brutal geopolitical realism: racism was never transcended; there’s not enough to go around; the global economy will have winners and losers; not all can sit at the table; and government policies should be organized around accepting these truths.” To soften the sting of that truth, however, Trump encourages, in Grandin’s words, “a petulant hedonism that forbids nothing and restrains nothing.”

Knowing where Grandin will lead us by no means saps the strength of his narrative. The power of the frontier metaphor was not exhausted by the settling of our lower-48 states, the process he expounds upon in such fine detail. The metaphor has been used for, in his words, “other arenas of expansion, to markets, war, culture, technology, science, the psyche, and politics.” JFK famously used the metaphor for America’s conquest of space. But some of our wisest Americans, such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whom Grandin quotes, have also questioned the “frontier ideal,” saying it “fed into multiple reinforcing pathologies: into racism, a violent masculinity, and moralism that celebrates the rich and punishes the poor.”

While appreciating Americans’ much-touted love of freedom as symbolized by the open frontier, Grandin definitely pursues the negative tenor of King’s observation with more vigor. Grandin never hesitates to point out villainy, and his opinion of our various presidents reveals his and their predilections. He is none too fond of the slave-holding Virginians, Washington, Jefferson, Madison and Monroe, but Andrew Jackson’s support for slavery, plus his perfidious and bloodthirsty treatment of Native Americans and Mexicans, attracts his explicit condemnation. Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt also rate very low with Grandin, both being condemned, as well, for racism. He even cites a statement by Teddy Roosevelt blaming the supposed raping of white women by black men for the South’s plague of lynching. (Such rapes, as historians have documented, rarely, if ever, occurred.) Also on Grandin’s bad list are Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, earlier Southern border-watchers. Two of the few presidents he seems to admire are John Quincy Adams, who disagreed with Jacksonian plundering of frontier assets, and FDR, whose New Deal was a positive “inversion” (Grandin’s term) of Turner’s Frontier Thesis. (It turns out Turner was FDR’s professor at Harvard.)

Grandin shares some shocking anecdotes sensitive Americans may long to forget. In his analysis of the “safety valve” metaphor, he carefully traces the actual device’s invention and use on various 19th century steam engines. What I will remember is this dire detail: “During Mississippi boat races, slaves were made to sit on the safety valve to build steam.” Deadly explosions were common. Other unexpected but memorable sights along Grandin’s narrative path include his account of a fondness for the Confederate flag not only among the South’s veterans but also vets of later wars with Mexico, Spain, the Axis powers and Korea. The Confederate flag was even flown by some U.S. soldiers in Vietnam. Equally ominous are Grandin’s accounts of white supremacism among our southern border patrol officers, beginning long before border interdictions were even formalized.

For Grandin, as mentioned, Trumpism represents the apotheosis of the frontier ideal, its transformation of America into a walled fortress for hoarding Caucasian treasures. But the strength of Grandin’s book is its sophisticated analysis of the light and darkness always implicit in the original myth itself. The frontier has always meant hope and freedom for some, abuse and even death for others. There is a similar tension inherent in America’s very concept of freedom. We insist on individual rights such as, in Grandin’s words, the rights “to have, to bear, to move, to assemble, to believe, to possess.” But social rights such as “to receive health care, education, and welfare” also exist, despite some people’s insistence that they are, to use his word, “perverse.”

In 1893 a young historian addressed the American Historical Association, which was meeting at the Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Frederick Jackson Turner presented his thesis, "The Significance of the Frontier in American History." He began by quoting from the Census of 1890:

"Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier of settlement, but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line."

Turner concluded his thesis, "The frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history." As if to confirm Turner, the Columbian Exposition displayed a small log cabin as an artifact.

Turner argued that the frontier had made the United States unique. Due to hardship, residents were forced to become resourceful and self-reliant. They developed strength and "rugged individualism," which in turn fostered the development of democracy. Turner paid no attention to women or the plight of Native Americans.

In many respects, Turner was reflecting the views of his generation. Americans generally thought of the frontier as a primeval wilderness, where men could live close to nature and be purified of civilization"s corruption. Many thought of the West as a social safety valve, where the poor could start a new life instead of succumbing to urban problems in large cities.

8613371530291

8613371530291