how does a pressure safety valve work manufacturer

Any system or vessel produces high levels of pressure, at times too much for the system to handle. However, there’s something that can ensure protection and consistent stable operation in overpressure events: high pressure relief valves.

In the event of an overpressure situation where the pressure of the system is above the regulator’s setpoint, these valves will vent gas or liquid away from the vessel or system to a safe location. This ensures consistently safe pressure levels and prevents damage and complete system failure. Once the vessel or system has normalized, the relief valves will close until they’re needed again.

High pressure relief valves are known to be one of the most reliable types of overpressure protection and present numerous benefits as well. For example, they don’t block normal flow through a line, and they don’t negatively affect regulators. On top of that, high pressure relief valves act as alarms during an overpressure event.

Safety valves tend to be used for more emergency situations. They operate similarly to high pressure valves, but they open instantly to their full capacity as soon as the system hits the set pressure of the valve.

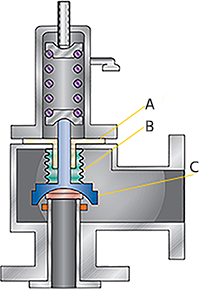

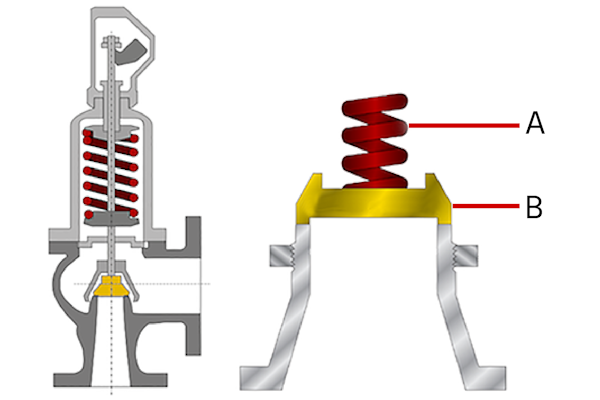

There are numerous types of high pressure relief valves. The most common are a spring-loaded pressure relief valve, a balanced bellows valve, and a balanced piston valve.

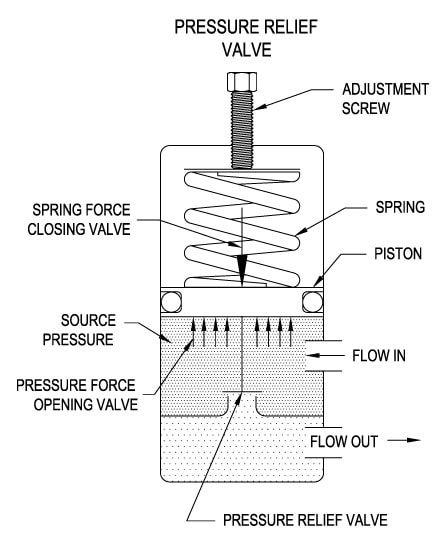

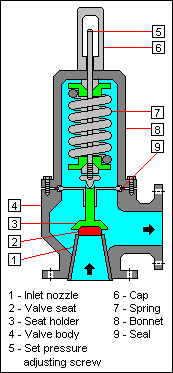

According to Wermac.org, the spring-loaded pressure relief valve is designed with a valve inlet or nozzle mounted on the pressurized system, a disc against the nozzle to prevent flow under normal system operating conditions, and a spring to hold the disc closed. This type of valve can also be adjusted to specific pressures.

Wermac.org also mentions that a balanced bellows valve and a balanced piston valve should be used when superimposed back pressure is variable. These valves include a pressure area equal to the seat area of the disc as well as a Bonnet that’s vented to keep the pressure area exposed to atmospheric pressure. This will also provide an easier way to detect leaks in the bellows or pistons.

Pressure relief valves (safety relief valves) are designed to open at a preset pressure and discharge fluid until pressure drops to acceptable levels. The development of the safety relief valve has an interesting history.

Denis Papin is credited by many sources as the originator of the first pressure relief valve (circa 1679) to prevent overpressure of his steam powered “digester”. His pressure relief design consisted of a weight suspended on a lever arm. When the force of the steam pressure acting on the valve exceeded the force of the weight acting through the lever arm the valve opened. Designs requiring a higher relief pressure setting required a longer lever arm and/or larger weights. This simple system worked however more space was needed and it coud be easily tampered with leading to a possible overpressure and explosion. Another disadvantage was premature opening of the valve if the device was subjected to bouncing movement.

Direct-acting deadweight pressure relief valves: Later to avoid the disadvantages of the lever arrangement, direct-acting deadweight pressure relief valves were installed on early steam locomotives. In this design, weights were applied directly to the top of the valve mechanism. To keep the size of the weights in a reasonable range, the valve size was often undersized resulting in a smaller vent opening than required. Often an explosion would occur as the steam pressure rose faster than the vent could release excess pressure. Bouncing movements also prematurely released pressure.

Direct acting spring valves: Timothy Hackworth is believed to be the first to use direct acting spring valves (circa 1828) on his locomotive engine called the Royal George. Timothy utilized an accordion arrangement of leaf springs, which would later be replaced with coil springs, to apply force to the valve. The spring force could be fine tuned by adjusting the nuts retaining the leaf springs.

Refinements to the direct acting spring relief valve design continued in subsequent years in response to the widespread use of steam boilers to provide heat and to power locomotives, river boats, and pumps. Steam boilers are less common today but the safety relief valve continues to be a critical component, in systems with pressure vessels, to protect against damage or catastrophic failure.

Each application has its own unique requirements but before we get into the selection process, let’s have a look at the operating principles of a typical direct acting pressure relief valve.

In operation, the pressure relief valve remains normally closed until pressures upstream reaches the desired set pressure. The valve will crack open when the set pressure is reached, and continue to open further, allowing more flow as over pressure increases. When upstream pressure falls a few psi below the set pressure, the valve will close again.

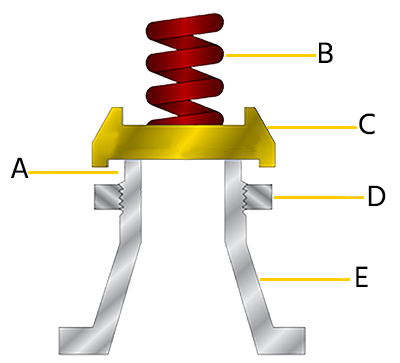

Most commonly, pressure relief valves employ a spring loaded “poppet” valve as a valve element. The poppet includes an elastomeric seal or, in some high pressure designs a thermoplastic seal, which is configured to make a seal on a valve seat. In operation, the spring and upstream pressure apply opposing forces on the valve. When the force of the upstream pressure exerts a greater force than the spring force, then the poppet moves away from the valve seat which allows fluid to pass through the outlet port. As the upstream pressure drops below the set point the valve then closes.

Piston style designs are often used when higher relief pressures are required, when ruggedness is a concern or when the relief pressure does not have to be held to a tight tolerance. Piston designs tend to be more sluggish, compared to diaphragm designs due to friction from the piston seal. In low pressure applications, or when high accuracy is required, the diaphragm style is preferred. Diaphragm relief valves employ a thin disc shaped element which is used to sense pressure changes. They are usually made of an elastomer, however, thin convoluted metal is used in special applications. Diaphragms essentially eliminate the friction inherent with piston style designs. Additionally, for a particular relief valve size, it is often possible to provide a greater sensing area with a diaphragm design than would be feasible with a piston style design.

The reference force element is usually a mechanical spring. This spring exerts a force on the sensing element and acts to close the valve. Many pressure relief valves are designed with an adjustment which allows the user to adjust the relief pressure set-point by changing the force exerted by the reference spring.

What is the maximum flow rate that the application requires? How much does the flow rate vary? Porting configuration and effective orifices are also important considerations.

The chemical properties of the fluid should be considered before determining the best materials for your application. Each fluid will have its own unique characteristics so care must be taken to select the appropriate body and seal materials that will come in contact with the fluid. The parts of the pressure relief valve in contact with the fluid are known as the “wetted” components. If the fluid is flammable or hazardous in nature the pressure relief valve must be capable of discharging it safely.

In many high technology applications space is limited and weight is a factor. Some manufactures specialize in miniature components and should be consulted. Material selection, particularly the relief valve body components, will impact weight. Also carefully consider the port (thread) sizes, adjustment styles, and mounting options as these will influence size and weight.

In many high technology applications space is limited and weight is a factor. Some manufactures specialize in miniature components and should be consulted. Material selection, particularly the relief valve body components, will impact weight. Also carefully consider the port (thread) sizes, adjustment styles, and mounting options as these will influence size and weight.

A wide range of materials are available to handle various fluids and operating environments. Common pressure relief valve component materials include brass, plastic, and aluminum. Various grades of stainless steel (such as 303, 304, and 316) are available too. Springs used inside the relief valve are typically made of music wire (carbon steel) or stainless steel.

Brass is suited to most common applications and is usually economical. Aluminum is often specified when weight is a consideration. Plastic is considered when low cost is of primarily concern or a throw away item is required. Stainless Steels are often chosen for use with corrosive fluids, when cleanliness of the fluid is a consideration or when the operating temperatures will be high.

Equally important is the compatibility of the seal material with the fluid and with the operating temperature range. Buna-N is a typical seal material. Optional seals are offered by some manufacturers and these include: Fluorocarbon, EPDM, Silicone, and Perfluoroelastomer.

The materials selected for the pressure relief valve not only need to be compatible with the fluid but also must be able to function properly at the expected operating temperature. The primary concern is whether or not the elastomer chosen will function properly throughout the expected temperature range. Additionally, the operating temperature may affect flow capacity and/or the spring rate in extreme applications.

Beswick Engineering manufactures four styles of pressure relief valves to best suit your application. The RVD and RVD8 are diaphragm based pressure relief valves which are suited to lower relief pressures. The RV2 and BPR valves are piston based designs.

As soon as mankind was able to boil water to create steam, the necessity of the safety device became evident. As long as 2000 years ago, the Chinese were using cauldrons with hinged lids to allow (relatively) safer production of steam. At the beginning of the 14th century, chemists used conical plugs and later, compressed springs to act as safety devices on pressurised vessels.

Early in the 19th century, boiler explosions on ships and locomotives frequently resulted from faulty safety devices, which led to the development of the first safety relief valves.

In 1848, Charles Retchie invented the accumulation chamber, which increases the compression surface within the safety valve allowing it to open rapidly within a narrow overpressure margin.

Today, most steam users are compelled by local health and safety regulations to ensure that their plant and processes incorporate safety devices and precautions, which ensure that dangerous conditions are prevented.

The principle type of device used to prevent overpressure in plant is the safety or safety relief valve. The safety valve operates by releasing a volume of fluid from within the plant when a predetermined maximum pressure is reached, thereby reducing the excess pressure in a safe manner. As the safety valve may be the only remaining device to prevent catastrophic failure under overpressure conditions, it is important that any such device is capable of operating at all times and under all possible conditions.

Safety valves should be installed wherever the maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP) of a system or pressure-containing vessel is likely to be exceeded. In steam systems, safety valves are typically used for boiler overpressure protection and other applications such as downstream of pressure reducing controls. Although their primary role is for safety, safety valves are also used in process operations to prevent product damage due to excess pressure. Pressure excess can be generated in a number of different situations, including:

The terms ‘safety valve’ and ‘safety relief valve’ are generic terms to describe many varieties of pressure relief devices that are designed to prevent excessive internal fluid pressure build-up. A wide range of different valves is available for many different applications and performance criteria.

In most national standards, specific definitions are given for the terms associated with safety and safety relief valves. There are several notable differences between the terminology used in the USA and Europe. One of the most important differences is that a valve referred to as a ‘safety valve’ in Europe is referred to as a ‘safety relief valve’ or ‘pressure relief valve’ in the USA. In addition, the term ‘safety valve’ in the USA generally refers specifically to the full-lift type of safety valve used in Europe.

Pressure relief valve- A spring-loaded pressure relief valve which is designed to open to relieve excess pressure and to reclose and prevent the further flow of fluid after normal conditions have been restored. It is characterised by a rapid-opening ‘pop’ action or by opening in a manner generally proportional to the increase in pressure over the opening pressure. It may be used for either compressible or incompressible fluids, depending on design, adjustment, or application.

Safety valves are primarily used with compressible gases and in particular for steam and air services. However, they can also be used for process type applications where they may be needed to protect the plant or to prevent spoilage of the product being processed.

Relief valve - A pressure relief device actuated by inlet static pressure having a gradual lift generally proportional to the increase in pressure over opening pressure.

Relief valves are commonly used in liquid systems, especially for lower capacities and thermal expansion duty. They can also be used on pumped systems as pressure overspill devices.

Safety relief valve - A pressure relief valve characterised by rapid opening or pop action, or by opening in proportion to the increase in pressure over the opening pressure, depending on the application, and which may be used either for liquid or compressible fluid.

In general, the safety relief valve will perform as a safety valve when used in a compressible gas system, but it will open in proportion to the overpressure when used in liquid systems, as would a relief valve.

Safety valve- A valve which automatically, without the assistance of any energy other than that of the fluid concerned, discharges a quantity of the fluid so as to prevent a predetermined safe pressure being exceeded, and which is designed to re-close and prevent further flow of fluid after normal pressure conditions of service have been restored.

A little product education can make you look super smart to customers, which usually means more orders for everything you sell. Here’s a few things to keep in mind about safety valves, so your customers will think you’re a genius.

A safety valve is required on anything that has pressure on it. It can be a boiler (high- or low-pressure), a compressor, heat exchanger, economizer, any pressure vessel, deaerator tank, sterilizer, after a reducing valve, etc.

There are four main types of safety valves: conventional, bellows, pilot-operated, and temperature and pressure. For this column, we will deal with conventional valves.

A safety valve is a simple but delicate device. It’s just two pieces of metal squeezed together by a spring. It is passive because it just sits there waiting for system pressure to rise. If everything else in the system works correctly, then the safety valve will never go off.

A safety valve is NOT 100% tight up to the set pressure. This is VERY important. A safety valve functions a little like a tea kettle. As the temperature rises in the kettle, it starts to hiss and spit when the water is almost at a boil. A safety valve functions the same way but with pressure not temperature. The set pressure must be at least 10% above the operating pressure or 5 psig, whichever is greater. So, if a system is operating at 25 psig, then the minimum set pressure of the safety valve would be 30 psig.

Most valve manufacturers prefer a 10 psig differential just so the customer has fewer problems. If a valve is positioned after a reducing valve, find out the max pressure that the equipment downstream can handle. If it can handle 40 psig, then set the valve at 40. If the customer is operating at 100 psig, then 110 would be the minimum. If the max pressure in this case is 150, then set it at 150. The equipment is still protected and they won’t have as many problems with the safety valve.

Here’s another reason the safety valve is set higher than the operating pressure: When it relieves, it needs room to shut off. This is called BLOWDOWN. In a steam and air valve there is at least one if not two adjusting rings to help control blowdown. They are adjusted to shut the valve off when the pressure subsides to 6% below the set pressure. There are variations to 6% but for our purposes it is good enough. So, if you operate a boiler at 100 psig and you set the safety valve at 105, it will probably leak. But if it didn’t, the blowdown would be set at 99, and the valve would never shut off because the operating pressure would be greater than the blowdown.

All safety valves that are on steam or air are required by code to have a test lever. It can be a plain open lever or a completely enclosed packed lever.

Safety valves are sized by flow rate not by pipe size. If a customer wants a 12″ safety valve, ask them the flow rate and the pressure setting. It will probably turn out that they need an 8×10 instead of a 12×16. Safety valves are not like gate valves. If you have a 12″ line, you put in a 12″ gate valve. If safety valves are sized too large, they will not function correctly. They will chatter and beat themselves to death.

Safety valves need to be selected for the worst possible scenario. If you are sizing a pressure reducing station that has 150 psig steam being reduced to 10 psig, you need a safety valve that is rated for 150 psig even though it is set at 15. You can’t put a 15 psig low-pressure boiler valve after the reducing valve because the body of the valve must to be able to handle the 150 psig of steam in case the reducing valve fails.

The seating surface in a safety valve is surprisingly small. In a 3×4 valve, the seating surface is 1/8″ wide and 5″ around. All it takes is one pop with a piece of debris going through and it can leak. Here’s an example: Folgers had a plant in downtown Kansas City that had a 6×8 DISCONTINUED Consolidated 1411Q set at 15 psig. The valve was probably 70 years old. We repaired it, but it leaked when plant maintenance put it back on. It was after a reducing valve, and I asked him if he played with the reducing valve and brought the pressure up to pop the safety valve. He said no, but I didn’t believe him. I told him the valve didn’t leak when it left our shop and to send it back.

When it came back, I laid it down on the outlet flange and looked up the inlet. There was a 12″ welding rod with the tip stuck between the seat and the disc. That rod was from the original construction and didn’t get blown out properly and just now it got set free. The maintenance guy didn’t believe me and came over and saw it for himself (this was before cell phones when you could take a picture).

If there is a problem with a safety valve, 99% of the time it is not the safety valve or the company that set it. There may be other reasons that the pressure is rising in the system before the safety valve. Some ethanol plants have a problem on starting up their boilers. The valves are set at 150 and they operate at 120 but at startup the pressure gets away from them and there is a spike, which creates enough pressure to cause a leak until things get under control.

If your customer is complaining that the valve is leaking, ask questions before a replacement is sent out. What is the operating pressure below the safety valve? If it is too close to the set pressure then they have to lower their operating pressure or raise the set pressure on the safety valve.

Is the valve installed in a vertical position? If it is on a 45-degree angle, horizontal, or upside down then it needs to be corrected. I have heard of two valves that were upside down in my 47 years. One was on a steam tractor and the other one was on a high-pressure compressor station in the New Mexico desert. He bought a 1/4″ valve set at 5,000 psig. On the outlet side, he left the end cap in the outlet and put a pin hole in it so he could hear if it was leaking or not. He hit the switch and when it got up to 3,500 psig the end cap came flying out like a missile past his nose. I told him to turn that sucker in the right direction and he shouldn’t have any problems. I never heard from him so I guess it worked.

If the set pressure is correct, and the valve is vertical, ask if the outlet piping is supported by something other than the safety valve. If they don’t have pipe hangers or a wall or something to keep the stress off the safety valve, it will leak.

There was a plant in Springfield, Mo. that couldn’t start up because a 2″ valve was leaking on a tank. It was set at 750 psig, and the factory replaced it 5 times. We are not going to replace any valves until certain questions are answered. I was called to solve the problem. The operating pressure was 450 so that wasn’t the problem. It was in a vertical position so we moved on to the piping. You could tell the guy was on his cell phone when I asked if there was any piping on the outlet. He said while looking at the installation that he had a 2″ line coming out into a 2×3 connection going up a story into a 3×4 connection and going up another story. I asked him if there was any support for this mess, and he hung up the phone. He didn’t say thank you, goodbye, or send me a Christmas present.

Pipe dope is another problem child. Make sure your contractors ease off on the pipe dope. That is enough for today, class. Thank you for your patience. And thank you for your business.

The Pressure Safety Valve Inspection article provides you information about inspection of pressure safety valve and pressure safety valve test in manufacturing shop as well as in operational plants.

Your pressure safety valve is a direct spring-loaded pressure-relief valve that is opened by the static pressure upstream of the valve and characterized by rapid opening or pop action.

When the static inlet pressure reaches the set pressure, it will increase the pressure upstream of the disk and overcome the spring force on the disk.

Your construction code for pressure safety valve is API Standard 526 and covers the minimum requirements for design, materials, fabrication, inspection, testing, and commissioning.

These are:API Recommended Practice 520 for Sizing and SelectionAPI Recommended practice 521 Guideline for Pressure Relieving and Depressing SystemsAPI Recommended Practice 527 Seat Tightness of Pressure Relief Valves

For example in the state of Minnesota the ASME Code application and stamping for pressure vessel and boiler is mandatory which “U” and “S” symbols are designated for stamping on the nameplate.

For example if there is pressure vessel need to be installed in the state of Minnesota then the pressure vessel nameplate shall be U stamped and pressure vessel safety valve shall be UV stamped.

National Board Inspection Code (NBIC) have own certification scheme for pressure safety valves and using NB symbol. The NBIC code book for this certification is NB 18.

National Board Inspection Code is assisting ASME organization for ASME UV symbol certification by providing ASME designee in manufactures auditing program.

There are some other standards and codes which are used in pressure safety valve such as:ASME PTC 25 for pressure relief devices which majorly is used for assessment of testing facility and apparatus for safety valvesBS EN ISO 4126-1, 4126-2 and 4126-3 which is construction standard similar to API STD 526.

This API RP 527 might be used in conjunction of API RP 576 as testing procedure for seat tightness testing of pressure safety valve for periodical servicing and inspection.

These are only important points or summery of points for pressure safety valve in-service inspection and should not be assumed as pressure safety valve inspection procedure.

Pressure safety valve inspection procedure is comprehensive document which need to cover inspection methods to be employed, equipment and material to be used, qualification of inspection personnel involved and the sequence of the inspection activities as minimum.

You may use following content as summery of points for Pressure Safety Valve Inspection in operational plantDetermination pressure safety valve inspection interval based API STD 510 and API RP 576 requirementsInspection of inlet and outlet piping after pressure safety valve removal for any foulingInspection of pressure safety valve charge and discharge nozzles for possible deposit and corrosion productsTaking care for proper handling of pressure safety valves from unit to the valve shop. The detail of handling and transportation instruction is provided in API RP 576.Controlling of seals for being intact when the valves arrived to the valve shop.Making as received POP test and recording the relieving pressure.

If the POP pressure is higher than the set pressure the test need to be repeated and if in the second effort it was near to the set pressure it is because of deposit.If in the second effort it was not opened near to the set pressure either it was set wrongly or it was changed during the operationIf the pressure safety valve was not opened in 150% of set pressure it should be considered as stuck shut.If the pressure safety valve was opened below the set pressure the spring is weakenedMaking external visual inspection on pressure safety valve after POP test. The test need contain following item as minimum;the flanges for pitting and roughness

Making body wall thickness measurementDismantling of pressure safety valve if the result of as received POP test was not satisfactoryMaking detail and comprehensive visual and dimensional inspection on the dismantled valve parts (after cleaning)Making special attention to the dismantled valves seating surfaces inspection e.g. disk and seat for roughness, wear and damage which might cause valve leakage in serviceReplacing the damaged parts in dismantled valves based manufacture recommendation and API RP 576 requirementsMaking precise setting of the pressure safety valve after reassembly based manufacture recommendation or NB-18 requirements

Making at least two POP test after setting and making sure the deviation from set pressure is not more than 2 psi for valves with set pressure equal or less than 70 psi or 3% for valves with set pressure higher than 70 psiMaking valve tightness test for leakage purpose after approval of the setting pressure and POP tests. The test method and acceptance criteria must be according to the API RP 576.The API RP 527 also can be used for pressure safety valve tightness test.Recording and maintaining the inspection and testing results.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Pressure relief devices are used to provide a means of venting excess pressure which could rupture a boiler or pressure vessel. A pressure relief device is the last line of defense for safety. If all other safety devices or operating controls fail, the pressure relief device must be capable of venting excess pressure.

There are many types of pressure relief devices available for use in the boiler and pressure vessel industry. This inspector guide will address the most common devices found on boilers and pressure vessels. Virtually all jurisdictions require a pressure relief device to be manufactured and certified in accordance with the ASME BPV Code in addition to being capacity-certified by the National Board.

Safety Valve – This device is typically used for steam or vapor service. It operates automatically with a full-opening pop action and recloses when the pressure drops to a value consistent with the blowdown requirements prescribed by the applicable governing code or standard.

Relief Valve – This device is typically used for liquid service. It operates automatically by opening farther as the pressure increases beyond the initial opening pressure and recloses when the pressure drops below the opening pressure.

Safety Relief Valve – This device includes the operating characteristics of both a safety valve and a relief valve and may be used in either application.

Temperature and Pressure Safety Relief Valve – This device is typically used on potable water heaters. In addition to its pressure-relief function, it also includes a temperature-sensing element which causes the device to open at a predetermined temperature regardless of pressure. The set temperature on these devices is usually 210°F.

Rupture Disk– This device is classified as nonreclosing since the disk is destroyed upon actuation. This type of device may be found in use with a pressure vessel where a spring-loaded pressure relief device is inappropriate due to the operating conditions or environment.

The inlet piping connected to the device must not be smaller in diameter than the inlet opening of the device. An inlet pipe that is smaller than the device inlet opening could alter the operating characteristics for which the device was designed.

The discharge piping connected to the device must be no smaller than the discharge opening of the device. A discharge pipe that is smaller than the device discharge opening could cause pressure to develop on the discharge side of the device while operating.

Multiple devices discharging into a discharge manifold or header is a common practice. The discharge manifold or header must be sized so the cross-sectional area is equal to or greater than the sum of the discharge cross-sectional areas of all the devices connected to the discharge manifold or header. Failing this requirement, the devices would be subjected to pressure on the discharge side of the device while operating. Even a small amount of pressure here could adversely affect the operation of the device.

Constant leakage of the device can cause a build-up of scale or other solids around the discharge opening. This build-up can prevent the device from operating as designed.

Discharge piping connected to the device must be supported so as not to impart any loadings on the body of the device. These loadings could affect or prevent the proper operation of the device including proper reclosure after operating.

Some devices, especially on larger boilers, may have a discharge pipe arrangement which incorporates provisions for expansion as the boiler heats up or cools down. These expansion provisions must allow the full range of movement required to prevent loads being applied to the device body.

Drain holes in the device body and discharge piping, when applicable, must be open to allow drainage of liquids from over the device disk on spring loaded valves. Any liquid allowed to remain on top of the device disk can adversely affect the operating characteristics of the device.

Most jurisdictional requirements state the device must be "piped to a point of safe discharge." This must be accomplished while keeping the run of discharge piping as short as possible. Most jurisdictions also limit the number of 90 degree elbows that may be installed in the discharge piping. Too long of a run and multiple elbows can adversely affect the operation of the device.

While inspecting a boiler or pressure vessel, the inspector will also be evaluating the pressure relief device(s) installed on, or associated with, the equipment. The inspector should:

Compare the device nameplate set pressure with the boiler or pressure vessel maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP) and ensure the device set pressure does not exceed the MAWP. A device with a set pressure less than MAWP is acceptable. If multiple devices are used, at least one must have a set pressure equal to or less than the MAWP. The ASME Code should be reviewed for other conditions relating to the use of multiple devices.

Ensure the device still has the device manufacturer"s seals intact. These seals can be in the form of wire through a drilled hole with a soft metal button, such as lead, crimped on the wire, or removable parts may be stake punched or crimped to inhibit accidental movement. Any evidence of the seal mechanism being broken or destroyed could indicate tampering. If this is found, the inspector should require replacement of the device or repair by a qualified organization.

Instruct the owner or owner"s representative to lift the test lever, if so equipped, on spring-loaded devices. ASME BPV Code Section IV devices can have the test levers lifted without pressure in the boiler. All other devices must have at least 75% of the device set pressure under the device disk prior to lifting the test lever. If the device is found to be stuck in a closed position, the equipment should be immediately removed from service until such time the device can be replaced or repaired.

Lifting the test lever of a spring-loaded device may not be practical in all cases when inspecting pressure vessels. The contents of the vessel may be hazardous. In these cases, the vessel owner/user should have a testing procedure in place which will ensure documented inspection and testing of the device at regular intervals.

The small pressure relief devices found on many air compressor vessels have a ring inserted through a drilled hole on the end of the device stem. These are tested by pulling the stem straight out and then releasing. The discharge openings in this type of device are holes drilled around the periphery of the device. These holes often get filled with oily dust and grit which can cause eye damage when the device is tested. A rag, loosely wrapped around the device when testing, can help prevent personal injury from the dust and grit.

Additional information to aid inspections of pressure relief devices, including installation requirements, can be found in the following publications and sources:

Pressure valves regulatethe flow of gas through a pipeline by opening or closing in response to changes in the pressure of the gas, air, water, or steam flowing through the pipe. Pressure valves are commonly used on natural gas systems, propane systems, and other types of gas systems.

A pressure valve regulates the flow of gas through pipelines by opening or closing in accordance with changes in the pressure of gas flowing through the pipe, thereby maintaining a constant pressure within the pipeline.

Pressure valves work by using a spring-loaded diaphragm or electrical actuator to open or close the valve in the pipeline. As the pressure inside the pipeline rises, the diaphragm moves away from the valve seat, allowing more gas to pass through. Conversely, as the pressure falls, the diaphragms move toward the valve seat, restricting the flow of gas.

Testing a pressure valve should be done before installing it into a system. If there are leaks in the pipe, the valve will not work properly. To test a pressure valve, use a leak detector to check for leaks in the pipe. Then, turn off the main supply line and connect a gauge to the valve. Turn the valve on slowly until the pressure reaches the desired level. Once the pressure has reached the desired level, turn the valve off and wait for the pressure to drop back down to normal levels.

Pressure valve control is used in many applications, but they’re mainly found in all pneumatic and hydraulic systems. Pressure valve control has a wide range of functions that can be used to maintain a set pressure level in a part of a control loop or to keep system pressures below a desired limit.

There are many different types of pressure valve control in the industry, such as pressure relief valves, pressure reducing valves, pressure safety valves, counterbalance valves, unloading valves, and sequencing valves. Most of these pressure valves are typically closed valves, but pressure reducing valves are commonly open valves. It’s important for most of these valves to have restrictions so that the required pressure control can be achieved.

The flow must be consistent at all times in certain applications. Injuries or deaths can be caused by variations in the flow of gases. That’s why pressure control valves are so important in the processing loop.

Pressure relief valves are used to keep the pneumatic and hydraulic systems under the desired pressure value. Based on the different installation positions, pressure relief valves have different functions as below. The downstream pressure should be reduced to a constant level whenever it goes over a threshold.

A pressure relief valve is usually made of three parts: a ball/diaphragm, a spring-loaded mechanism, and a valve nozzle. A spring-loaded mechanism is placed in the valve’s housing, which is used to close the orifice. The pressure relief valve’s spring-loaded mechanism can be adjusted to change the pressure on the spring mechanism. If you want to increase the set pressure limit, just simply increase the pressure on the valve spring-load mechanism directly. If you want to decrease the set pressure limit, only decrease the pressure on the spring-load mechanism directly. A relief valve set-pressure can be specified by the manufacturer if there is no adjustability. When the set pressure is reached, the pressure overcomes the spring pressure and pushes the ball or diaphragm back opening the orifice and releasing the excess pressure. Depending on the media, it is either released into the atmosphere or discharged into it. It is possible to return to a tank or pumping circuit with compressed air.

There are two types of PRVs used in industry, one is the direct-acting pressure reducing valves, and the other type is pilot operated pressure reducing valves. The pressure reducing valves use globe type or angle type valve bodies. Most of the time, the main type of valve used in water systems is the direct acting valve, which consists of a globe-type body with a spring-loaded, heat-resistant diaphragm connected to the outlet of the valve that acts upon a spring. This spring holds a pre-set tension on the PRVs seat that’s installed with a pressure equalizing mechanism for precise water pressure control.

Pressure reducing valves are widely used in water conditions, such as in buildings, industrial plants, water treatment plants, homes, and so on. It will automatically reduce the water pressure from the main supply, in case to lower the water pressure to the destination and more sensible pressure for equipment.

Sequence valves are widely used in hydraulic systems, and are a type of pressure valve. Sequence valves are similar to pressure relief valves, but are used to control a set of pressure-related operating sequences. The main function of a sequence valve is to divert the flow in a predetermined sequence, and its construction is very similar to a pressure relief valve, which is a pressure actuated valve, usually a closed valve.

The sequence valve works on the principle that the valve plug will be moved when the main system pressure exceeds the spring setting. As a result, the outlet of the sequence valve will remain closed until the upstream pressure rises to a predetermined value, and then the valve will open, allowing air to transfer from the inlet to the outlet. Sequence valves are primarily used to force two actuators to operate in sequence. One nice feature of the sequence valve is that the valve has a separate drain connection to the spring chamber, under normal operating conditions, high pressures may occur at the output port. When the pressure rises above its limit, the pressure sequence valve will allow flow to occur in another part of the system. The pressure sequence valve is installed in a pneumatic control and its switching operation requires a specific pressure.

Counterbalance valves are used to handle loads that are over-limited and to safely suspend loads, these valves commonly work with hydraulic cylinders. This type of valve can also be used with hydraulic motors and is then commonly referred to as a brake valve. Both counterbalance valves and pilot-operated check valves can be used to lock the fluid in the cylinder to prevent drift. However, pilot-operated check valves cannot control over-running loads. A counterbalance valve should be used when uncontrolled motion may occur with an overrunning load.

The pressure safety valve is one of the most critical automatic safety devices in a pressure system, and in many cases is the last line of defense for safety. The important function of a pressure safety valve is overpressure protection, so ensure that the pressure safety valve can operate properly in any situation. Pressure safety valves are mainly used in pressurized vessels or equipment to protect the environment, property safety, and life safety in the event of an overpressure event. A pressure safety valve opens and releases excess pressure in a vessel or equipment, and closes again when normal conditions are restored and prevents the further release of fluid.

A safety valve is a valve that acts as a fail-safe. An example of safety valve is a pressure relief valve (PRV), which automatically releases a substance from a boiler, pressure vessel, or other system, when the pressure or temperature exceeds preset limits. Pilot-operated relief valves are a specialized type of pressure safety valve. A leak tight, lower cost, single emergency use option would be a rupture disk.

Safety valves were first developed for use on steam boilers during the Industrial Revolution. Early boilers operating without them were prone to explosion unless carefully operated.

Vacuum safety valves (or combined pressure/vacuum safety valves) are used to prevent a tank from collapsing while it is being emptied, or when cold rinse water is used after hot CIP (clean-in-place) or SIP (sterilization-in-place) procedures. When sizing a vacuum safety valve, the calculation method is not defined in any norm, particularly in the hot CIP / cold water scenario, but some manufacturers

The earliest and simplest safety valve was used on a 1679 steam digester and utilized a weight to retain the steam pressure (this design is still commonly used on pressure cookers); however, these were easily tampered with or accidentally released. On the Stockton and Darlington Railway, the safety valve tended to go off when the engine hit a bump in the track. A valve less sensitive to sudden accelerations used a spring to contain the steam pressure, but these (based on a Salter spring balance) could still be screwed down to increase the pressure beyond design limits. This dangerous practice was sometimes used to marginally increase the performance of a steam engine. In 1856, John Ramsbottom invented a tamper-proof spring safety valve that became universal on railways. The Ramsbottom valve consisted of two plug-type valves connected to each other by a spring-laden pivoting arm, with one valve element on either side of the pivot. Any adjustment made to one of valves in an attempt to increase its operating pressure would cause the other valve to be lifted off its seat, regardless of how the adjustment was attempted. The pivot point on the arm was not symmetrically between the valves, so any tightening of the spring would cause one of the valves to lift. Only by removing and disassembling the entire valve assembly could its operating pressure be adjusted, making impromptu "tying down" of the valve by locomotive crews in search of more power impossible. The pivoting arm was commonly extended into a handle shape and fed back into the locomotive cab, allowing crews to "rock" both valves off their seats to confirm they were set and operating correctly.

Safety valves also evolved to protect equipment such as pressure vessels (fired or not) and heat exchangers. The term safety valve should be limited to compressible fluid applications (gas, vapour, or steam).

For liquid-packed vessels, thermal relief valves are generally characterized by the relatively small size of the valve necessary to provide protection from excess pressure caused by thermal expansion. In this case a small valve is adequate because most liquids are nearly incompressible, and so a relatively small amount of fluid discharged through the relief valve will produce a substantial reduction in pressure.

Flow protection is characterized by safety valves that are considerably larger than those mounted for thermal protection. They are generally sized for use in situations where significant quantities of gas or high volumes of liquid must be quickly discharged in order to protect the integrity of the vessel or pipeline. This protection can alternatively be achieved by installing a high integrity pressure protection system (HIPPS).

In the petroleum refining, petrochemical, chemical manufacturing, natural gas processing, power generation, food, drinks, cosmetics and pharmaceuticals industries, the term safety valve is associated with the terms pressure relief valve (PRV), pressure safety valve (PSV) and relief valve.

The generic term is Pressure relief valve (PRV) or pressure safety valve (PSV). PRVs and PSVs are not the same thing, despite what many people think; the difference is that PSVs have a manual lever to open the valve in case of emergency.

Relief valve (RV): an automatic system that is actuated by the static pressure in a liquid-filled vessel. It specifically opens proportionally with increasing pressure

Pilot-operated safety relief valve (POSRV): an automatic system that relieves on remote command from a pilot, to which the static pressure (from equipment to protect) is connected

Low pressure safety valve (LPSV): an automatic system that relieves static pressure on a gas. Used when the difference between the vessel pressure and the ambient atmospheric pressure is small.

Vacuum pressure safety valve (VPSV): an automatic system that relieves static pressure on a gas. Used when the pressure difference between the vessel pressure and the ambient pressure is small, negative and near to atmospheric pressure.

Low and vacuum pressure safety valve (LVPSV): an automatic system that relieves static pressure on a gas. Used when the pressure difference is small, negative or positive and near to atmospheric pressure.

In most countries, industries are legally required to protect pressure vessels and other equipment by using relief valves. Also, in most countries, equipment design codes such as those provided by the ASME, API and other organizations like ISO (ISO 4126) must be complied with. These codes include design standards for relief valves and schedules for periodic inspection and testing after valves have been removed by the company engineer.

Today, the food, drinks, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals industries call for hygienic safety valves, fully drainable and Cleanable-In-Place. Most are made of stainless steel; the hygienic norms are mainly 3A in the USA and EHEDG in Europe.

The first safety valve was invented by Denis Papin for his steam digester, an early pressure cooker rather than an engine.steelyard" lever a smaller weight was required, also the pressure could easily be regulated by sliding the same weight back and forth along the lever arm. Papin retained the same design for his 1707 steam pump.Greenwich in 1803, one of Trevithick"s high-pressure stationary engines exploded when the boy trained to operate the engine left it to catch eels in the river, without first releasing the safety valve from its working load.

Although the lever safety valve was convenient, it was too sensitive to the motion of a steam locomotive. Early steam locomotives therefore used a simpler arrangement of weights stacked directly upon the valve. This required a smaller valve area, so as to keep the weight manageable, which sometimes proved inadequate to vent the pressure of an unattended boiler, leading to explosions. An even greater hazard was the ease with which such a valve could be tied down, so as to increase the pressure and thus power of the engine, at further risk of explosion.

Although deadweight safety valves had a short lifetime on steam locomotives, they remained in use on stationary boilers for as long as steam power remained.

Weighted valves were sensitive to bouncing from the rough riding of early locomotives. One solution was to use a lightweight spring rather than a weight. This was the invention of Timothy Hackworth on his leaf springs.

These direct-acting spring valves could be adjusted by tightening the nuts retaining the spring. To avoid tampering, they were often shrouded in tall brass casings which also vented the steam away from the locomotive crew.

The Salter coil spring spring balance for weighing, was first made in Britain by around 1770.spring steels to make a powerful but compact spring in one piece. Once again by using the lever mechanism, such a spring balance could be applied to the considerable force of a boiler safety valve.

The spring balance valve also acted as a pressure gauge. This was useful as previous pressure gauges were unwieldy mercury manometers and the Bourdon gauge had yet to be invented.

Paired valves were often adjusted to slightly different pressures too, a small valve as a control measure and the lockable valve made larger and permanently set to a higher pressure, as a safeguard.Sinclair for the Eastern Counties Railway in 1859, had the valve spring with pressure scale behind the dome, facing the cab, and the locked valve ahead of the dome, out of reach of interference.

In 1855, John Ramsbottom, later locomotive superintendent of the LNWR, described a new form of safety valve intended to improve reliability and especially to be tamper-resistant. A pair of plug valves were used, held down by a common spring-loaded lever between them with a single central spring. This lever was characteristically extended rearwards, often reaching into the cab on early locomotives. Rather than discouraging the use of the spring lever by the fireman, Ramsbottom"s valve encouraged this. Rocking the lever freed up the valves alternately and checked that neither was sticking in its seat.

A drawback to the Ramsbottom type was its complexity. Poor maintenance or mis-assembly of the linkage between the spring and the valves could lead to a valve that no longer opened correctly under pressure. The valves could be held against their seats and fail to open or, even worse, to allow the valve to open but insufficiently to vent steam at an adequate rate and so not being an obvious and noticeable fault.Rhymney Railway, even though the boiler was almost new, at only eight months old.

Naylor valves were introduced around 1866. A bellcrank arrangement reduced the strain (percentage extension) of the spring, thus maintaining a more constant force.L&Y & NER.

All of the preceding safety valve designs opened gradually and had a tendency to leak a "feather" of steam as they approached "blowing-off", even though this was below the pressure. When they opened they also did so partially at first and didn"t vent steam quickly until the boiler was well over pressure.

The quick-opening "pop" valve was a solution to this. Their construction was simple: the existing circular plug valve was changed to an inverted "top hat" shape, with an enlarged upper diameter. They fitted into a stepped seat of two matching diameters. When closed, the steam pressure acted only on the crown of the top hat, and was balanced by the spring force. Once the valve opened a little, steam could pass the lower seat and began to act on the larger brim. This greater area overwhelmed the spring force and the valve flew completely open with a "pop". Escaping steam on this larger diameter also held the valve open until pressure had dropped below that at which it originally opened, providing hysteresis.

These valves coincided with a change in firing behaviour. Rather than demonstrating their virility by always showing a feather at the valve, firemen now tried to avoid noisy blowing off, especially around stations or under the large roof of a major station. This was mostly at the behest of stationmasters, but firemen also realised that any blowing off through a pop valve wasted several pounds of boiler pressure; estimated at 20 psi lost and 16 lbs or more of shovelled coal.

Pop valves derived from Adams"s patent design of 1873, with an extended lip. R. L. Ross"s valves were patented in 1902 and 1904. They were more popular in America at first, but widespread from the 1920s on.

Although showy polished brass covers over safety valves had been a feature of steam locomotives since Stephenson"s day, the only railway to maintain this tradition into the era of pop valves was the GWR, with their distinctive tapered brass safety valve bonnets and copper-capped chimneys.

Developments in high-pressure water-tube boilers for marine use placed more demands on safety valves. Valves of greater capacity were required, to vent safely the high steam-generating capacity of these large boilers.Naylor valve) became more critical.distilled feedwater and also a scouring of the valve seats, leading to wear.

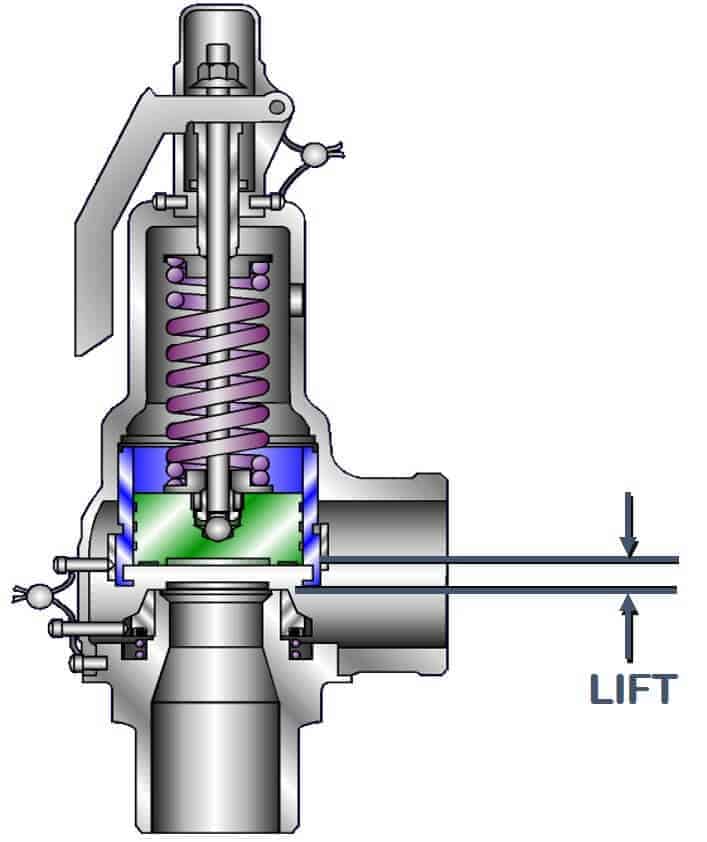

High-lift safety valves are direct-loaded spring types, although the spring does not bear directly on the valve, but on a guide-rod valve stem. The valve is beneath the base of the stem, the spring rests on a flange some height above this. The increased space between the valve itself and the spring seat allows the valve to lift higher, further clear of the seat. This gives a steam flow through the valve equivalent to a valve one and a half or twice as large (depending on detail design).

The Cockburn Improved High Lift design has similar features to the Ross pop type. The exhaust steam is partially trapped on its way out and acts on the base of the spring seat, increasing the lift force on the valve and holding the valve further open.

To optimise the flow through a given diameter of valve, the full-bore design is used. This has a servo action, where steam through a narrow control passage is allowed through if it passes a small control valve. This steam is then not exhausted, but is passed to a piston that is used to open the main valve.

There are safety valves known as PSV"s and can be connected to pressure gauges (usually with a 1/2" BSP fitting). These allow a resistance of pressure to be applied to limit the pressure forced on the gauge tube, resulting in prevention of over pressurisation. the matter that has been injected into the gauge, if over pressurised, will be diverted through a pipe in the safety valve, and shall be driven away from the gauge.

There is a wide range of safety valves having many different applications and performance criteria in different areas. In addition, national standards are set for many kinds of safety valves.

Safety valves are required on water heaters, where they prevent disaster in certain configurations in the event that a thermostat should fail. Such a valve is sometimes referred to as a "T&P valve" (Temperature and Pressure valve). There are still occasional, spectacular failures of older water heaters that lack this equipment. Houses can be leveled by the force of the blast.

Pressure cookers are cooking pots with a pressure-proof lid. Cooking at pressure allows the temperature to rise above the normal boiling point of water (100 degrees Celsius at sea level), which speeds up the cooking and makes it more thorough.

Pressure cookers usually have two safety valves to prevent explosions. On older designs, one is a nozzle upon which a weight sits. The other is a sealed rubber grommet which is ejected in a controlled explosion if the first valve gets blocked. On newer generation pressure cookers, if the steam vent gets blocked, a safety spring will eject excess pressure and if that fails, the gasket will expand and release excess pressure downwards between the lid and the pan. Also, newer generation pressure cookers have a safety interlock which locks the lid when internal pressure exceeds atmospheric pressure, to prevent accidents from a sudden release of very hot steam, food and liquid, which would happen if the lid were to be removed when the pan is still slightly pressurised inside (however, the lid will be very hard or impossible to open when the pot is still pressurised).

These figures are based on two measurements, a drop from 225 psi to 205 psi for an LNER Class V2 in 1952 and a smaller drop of 10 psi estimated in 1953 as 16 lbs of coal.

"Trial of HMS Rattler and Alecto". April 1845. The very lowest pressure exhibited "when the screw was out of the water" (as the opponents of the principle term it) was 34 lb, ranging up to 60 lb., on Salter"s balance.

An overpressure event refers to any condition which would cause pressure in a vessel or system to increase beyond the specified design pressure or maximum allowable working pressure (MAWP).

Many electronic, pneumatic and hydraulic systems exist today to control fluid system variables, such as pressure, temperature and flow. Each of these systems requires a power source of some type, such as electricity or compressed air in order to operate. A pressure Relief Valve must be capable of operating at all times, especially during a period of power failure when system controls are nonfunctional. The sole source of power for the pressure Relief Valve, therefore, is the process fluid.

Once a condition occurs that causes the pressure in a system or vessel to increase to a dangerous level, the pressure Relief Valve may be the only device remaining to prevent a catastrophic failure. Since reliability is directly related to the complexity of the device, it is important that the design of the pressure Relief Valve be as simple as possible.

The pressure Relief Valve must open at a predetermined set pressure, flow a rated capacity at a specified overpressure, and close when the system pressure has returned to a safe level. Pressure Relief Valves must be designed with materials compatible with many process fluids from simple air and water to the most corrosive media. They must also be designed to operate in a consistently smooth and stable manner on a variety of fluids and fluid phases.

The basic spring loaded pressure Relief Valve has been developed to meet the need for a simple, reliable, system actuated device to provide overpressure protection.

The Valve consists of a Valve inlet or nozzle mounted on the pressurized system, a disc held against the nozzle to prevent flow under normal system operating conditions, a spring to hold the disc closed, and a body/Bonnet to contain the operating elements. The spring load is adjustable to vary the pressure at which the Valve will open.

When a pressure Relief Valve begins to lift, the spring force increases. Thus system pressure must increase if lift is to continue. For this reason pressure Relief Valves are allowed an overpressure allowance to reach full lift. This allowable overpressure is generally 10% for Valves on unfired systems. This margin is relatively small and some means must be provided to assist in the lift effort.

Most pressure Relief Valves, therefore, have a secondary control chamber or huddling chamber to enhance lift. As the disc begins to lift, fluid enters the control chamber exposing a larger area of the disc to system pressure.

This causes an incremental change in force which overcompensates for the increase in spring force and causes the Valve to open at a rapid rate. At the same time, the direction of the fluid flow is reversed and the momentum effect resulting from the change in flow direction further enhances lift. These effects combine to allow the Valve to achieve maximum lift and maximum flow within the allowable overpressure limits. Because of the larger disc area exposed to system pressure after the Valve achieves lift, the Valve will not close until system pressure has been reduced to some level below the set pressure. The design of the control chamber determines where the closing point will occur.

When superimposed back pressure is variable, a balanced bellows or balanced piston design is recommended. A typical balanced bellow is shown on the right. The bellows or piston is designed with an effective pressure area equal to the seat area of the disc. The Bonnet is vented to ensure that the pressure area of the bellows or piston will always be exposed to atmospheric pressure and to provide a telltale sign should the bellows or piston begin to leak. Variations in back pressure, therefore, will have no effect on set pressure. Back pressure may, however, affect flow.

A safety Valve is a pressure Relief Valve actuated by inlet static pressure and characterized by rapid opening or pop action. (It is normally used for steam and air services.)

A low-lift safety Valve is a safety Valve in which the disc lifts automatically such that the actual discharge area is determined by the position of the disc.

A full-lift safety Valve is a safety Valve in which the disc lifts automatically such that the actual discharge area is not determined by the position of the disc.

A Relief Valve is a pressure relief device actuated by inlet static pressure having a gradual lift generally proportional to the increase in pressure over opening pressure. It may be provided with an enclosed spring housing suitable for closed discharge system application and is primarily used for liquid service.

A safety Relief Valve is a pressure Relief Valve characterized by rapid opening or pop action, or by opening in proportion to the increase in pressure over the opening pressure, depending on the application and may be used either for liquid or compressible fluid.

A conventional safety Relief Valve is a pressure Relief Valve which has its spring housing vented to the discharge side of the Valve. The operational characteristics (opening pressure, closing pressure, and relieving capacity) are directly affected by changes of the back pressure on the Valve.

A b

8613371530291

8613371530291