justice safety valve act of 2013 made in china

The Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013 (H.R. 1695 in the House or S. 619 in the Senate) is a bill in the 113th United States Congress.minimum sentences under certain circumstances.

The bill amends the federal criminal US code of the United States title 18, Part II, Chapter 227, Subchapter A, Section 3553 Imposition of a Sentence. It aimed to authorize a federal court to impose a sentence below a statutory minimum if necessary to avoid violating federal provisions prescribing factors courts must consider in imposing a sentence. It requires the court to give parties notice of its intent to impose a lower sentence and to state in writing the factors requiring such a sentence.

On November 21, 2013, the United States Senate Judiciary Committee convened in a rescheduled Executive Business Meeting. The meeting was to discuss and possibly vote on moving forward with the Justice Safety Valve Act. Other related Acts include the S.1410, "The Smarter Sentencing Act of 2013" (Durbin, Lee, Leahy, Whitehouse) and

S.1675, Recidivism Reduction and Public Safety Act of 2013 (Whitehouse, Portman). The Justice Safety Valve Act became one of many new bills to address prison overcrowding and the soaring cost to the American taxpayers. A quorum was not present at the meeting and the Chairman had to postpone discussion and possible vote on the Justice Safety Valve Act. The bills were held over by the Senate Judiciary Committee through the end of 2013 and January 2014. The bills were worked on to merge the language of the Smarter Sentencing Act (H.R. 3382/S. 1410) and the Justice Safety Valve Act (H.R. 1695/S. 619) along with a new bill, S. 1783 the Federal Prison Reform Act of 2013, introduced by John Cornyn (R-TX).

The bill summary was written by the Congressional Research Service, a nonpartisan division of the Library of Congress. It reads, "Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013 - Amends the federal criminal code to authorize a federal court to impose a sentence below a statutory minimum if necessary to avoid violating federal provisions prescribing factors courts must consider in imposing a sentence. Requires the court to give the parties notice of its intent to impose a lower sentence and to state in writing the factors requiring such a sentence."

113th Congress (2013) (April 24, 2013). "H.R. 1695: Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013". Legislation. GovTrack.us. Retrieved October 26, 2013. Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013

(Washington, DC) – A major criminal justice reform bill introduced in the US Congress on June 25, 2015, could improve the fairness of federal prison sentencing and better protect the rights of prisoners, Human Rights Watch said today. The bill, the Safe, Accountable, Fair, Effective (SAFE) Justice Act, is sponsored by Representatives Jim Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin and Bobby Scott of Virginia.

“Federal prisons are filled beyond capacity with people serving grotesquely long sentences,” said Antonio Ginatta, US advocacy director at Human Rights Watch. “The SAFE Justice Act proposes thoughtful reforms that address some of the abuses of the ‘tough on crime’ era.”

The SAFE Justice Act proposes reforms throughout all stages of the criminal justice process, from pretrial detention to post-confinement probation. It embraces general criminal justice principles supported by Human Rights Watch, including, for example, eligibility for retroactive application of sentence reductions. Several sections of the bill specifically propose reforms that were analyzed in several recent Human Rights Watch reports:

The SAFE Justice Act would reform federal sentencing statutes to promote fairer results. It would modify mandatory minimum sentences so that they exclude people whose role in a drug trafficking offense is low-level or minimal. The bill also would give judges more discretion through “safety valves” to impose sentences on drug offenders shorter than those required by mandatory minimums. And it would narrow sentencing enhancements that currently can turn a 10-year sentence into a life sentence due to prior drug crimes. With these reforms, prosecutors would no longer be able to threaten disproportionately long and unfair sentences in federal drug cases, as Human Rights Watch documented in a 2013 report.

The bill would also make much needed changes to the federal compassionate release program. As Human Rights Watch reported in 2012, the US Bureau of Prisons has underused the compassionate release program, which allows for people in prison to be released for “extraordinary and compelling” reasons. The SAFE Justice Act would give people in prison the right to petition a court directly for compassionate release – without requiring Bureau of Prison approval as is currently the case – and allow for a prisoner to seek compassionate release in cases involving the death or incapacitation of their child’s primary caregiver.

The SAFE Justice Act would require the US Attorney General to provide training to federal correctional staff on how to better identify and respond to people with mental disabilities under their custody as well as on de-escalation techniques for their responses. This provision is consistent with a key recommendation from a recent Human Rights Watch report on use of force against inmates with mental disabilities.

The SAFE Justice Act is the outcome of the House Judiciary Committee’s task force on over-criminalization, chaired by Sensenbrenner, with Scott as its ranking member. Authorized in 2013, the task force assessed the massive growth of federal criminal offenses and the soaring federal prison population since the 1980s. Human Rights Watch submitted testimony to the task force addressing the issue of disproportionately long federal sentences.

The introduction of the SAFE Justice Act in the House of Representatives follows the introduction of several reform-minded bills in the Senate, including the Smarter Sentencing Act – which would cut the length of certain mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses in half – and the flawed CORRECTIONS Act, which, as introduced, fails to address mandatory minimum sentences and sentencing enhancements at all.

Congress should pass the SAFE Justice Act as well as additional reforms to bring federal sentencing in line with principles of proportionality, fairness, and respect for human dignity, Human Rights Watch said.

“The SAFE Justice Act is not a cure-all, but a smartly crafted bill that would better align the federal prison system with its human rights obligations,” Ginatta said. “It’s a promising vehicle for change.”

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Chairwoman Jackson Lee, Ranking Member Biggs, and members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to submit a statement for the record for this critical hearing. On behalf of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a coalition charged by its diverse membership of more than 220 national organizations to promote and protect civil and human rights in the United States, I write to underscore the critical need for sentencing reform and urge the Subcommittee and all of Congress to heed President Biden’s call for the end of mandatory minimums and other overly-punitive policies that undermine the very foundation of justice in our country.

Over the past five decades, U.S. criminal-legal policies have driven an increase in incarceration rates that is unprecedented in this country’s history and unmatched globally: the United States incarcerates more people than any other country in the world, with more than 2 million people currently incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails.[1] Over-criminalization and over-incarceration have devastating impacts on those ensnared in the criminal-legal system and on their families, do not produce any proportional increase in public safety, and disproportionately harm low-income communities and communities of color. In particular, mandatory minimum penalties are a key driver of the burgeoning prison population, and eliminating them is crucial to any sentencing reform legislation. The Leadership Conference is categorically opposed to mandatory minimums sentences, and urges Congress to take steps toward repairing the damage wrought by these penalties by ending blanket policies that do not allow for judicial discretion and promoting alternatives to arrest and incarceration.

Since the mid-20th century, Congress has expanded its use of mandatory minimum penalties by broadening it to include different offenses and lengthening the mandatory minimum sentences.[2] The proliferation of the use of mandatory minimum sentences has fueled skyrocketing prison populations.[3] The federal prison population has increased from approximately 25,000 in FY1980 to nearly 152,894 today.[4] For each year between 1980 and 2013, federal prisons added almost 6,000 more inmates than the previous year.[5] As of 2016, 55% of the federal prison population was comprised of those who had been sentenced under a mandatory minimum provision.[6] While drops in prosecutions and in the severity of sentences for drug-related crime, as well as releases due to the COVID-19 pandemic, have led to a decline in the federal prison population in recent years, by and large these piecemeal changes are insufficient to reverse nearly forty years of explosive growth.[7] The Bureau of Prisons’ (BOP) budget has grown in tandem: the President’s FY22 budget request for BOP is $8 billion, which accounts for nearly a quarter of the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) entire budget.[8]

Draconian drug laws and their resulting enforcement are the source of much of this growth. Under the banner of the War on Drugs, the Reagan administration imposed particularly harsh mandatory minimum penalties for drug offenses under the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 and dedicated more than a billion dollars ($2.3 billion in today’s dollars) to law enforcement efforts to increase drug arrests. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (known colloquially as the 1994 Crime Bill) instituted a “three strikes” penalty that mandated a life sentence for anyone convicted of certain prior drug or violent felonies and incentivized states to adopt similar ‘tough-on-crime’ policies.[9] The “arrest-first” policies of the 1980s and ‘90s led to a surge in drug arrests, with a particularly large impact on cannabis arrests,[10] and an attendant use of long mandatory minimum sentences that caused the federal prison population to explode. The Urban Institute has found that increases in expected time served for drug offenses was the largest contributor to growth in the federal prison population between 1998 and 2010.[11] The Charles Colson Task Force on Federal Corrections, a Congressionally-mandated, bipartisan organization, attributes the growth both to the number of people admitted to prison for drug crimes as well as to the increased length of their sentences.[12] Currently, people convicted of drug offenses make up 46.3 percent of the BOP population.[13]

Yet, despite the dramatic uptick in incarceration, there is no indication that these sentences deter crime, protect public safety, or decrease drug use or trafficking. Increasing the severity of punishment has little impact on crime deterrence, and studies of federal drug laws show no significant relationship between drug imprisonment rates and drug use or recidivism.[14] The punishment-based approach to the War on Drugs, with its dramatic increase in the use of mandatory minimums — and corresponding increase in incarceration — has produced lasting harm in communities across the country while having little effect on actual drug use or crime. Unfortunately, the myth that punishment and harsh mandatory minimums will reduce drug use and crime persists in real and consequential ways: just this past April, Congress extended the temporary “class wide” emergency scheduling of fentanyl-related substances, which will exacerbate untenable federal sentencing trends and give rise to harsh mandatory minimum penalties for offenses involving fentanyl analogues.[15] Statistics about the growth in mass incarceration due to mandatory minimums, combined with data showing they have no positive effect on public safety, illustrate the harmful impact of these sentences on prison growth and the need to turn away from such antiquated “tough on crime” policies.

Mandatory minimums also eliminate judicial discretion, preventing judges from tailoring punishment to a particular defendant by taking into account an individual’s background and the circumstances of his or her offenses when determining his or her sentence. Mandatory minimums instead place more power in the hands of prosecutors and their charging decisions, which is particularly concerning given that prosecutors are more likely to charge Black people with a crime that carries a mandatory minimum than a White person.[16] Mass incarceration as a whole has had a markedly disproportionate impact on communities of color. Today, BOP reports that 38 percent of its current prison population is Black and 30.2 percent is Hispanic, an enormous disparity given that both groups represent only about one third of the nation’s population combined.[17] These disparities are also reflected in mandatory minimum penalties. In a 2017 review of mandatory minimum sentencing policies, the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that Black people in BOP custody were more likely to have been convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum penalty than any other group.[18] Hispanic and Black people accounted for a majority of those convicted with an offense carrying a drug mandatory minimum,[19] despite the fact that White and Black people use illicit substances at roughly the same rate, and Hispanic people use such substances at a lower rate.[20] The study also showed that Black people were the least likely to receive relief from mandatory minimum sentences compared to White and Hispanic people.[21] Finally, the review found racial disparities in convictions of a federal offense subject to a mandatory minimum penalty: 73.2 percent of Black people convicted of a federal offense received a mandatory minimum sentence, compared to 70 percent of White people and 46.9 percent of Hispanic people.[22] It is clear that mandatory minimums create stark racial disparities in federal sentencing.

Congress has made some progress toward addressing the harms of mandatory minimums. In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA), which reduced the disparities between the mandatory penalties for crack and powder cocaine from 100:1 to 18:1. Building on this legislation, the First Step Act of 2018 made necessary, though modest, improvements to the federal sentencing scheme by making the FSA retroactive and through expanding the federal safety valve, which permits a sentencing court to disregard minimum sentences for low-level, nonviolent defendants. Under this provision, judges have discretion to make a person eligible for the safety valve in cases where the seriousness of his or her record is over-represented, or it is unlikely he or she would commit other crimes. The law also reformed and reduced the unfair three-strike mandatory minimum sentence from life to 25 years. The First Step Act further eliminated 924(c) stacking, which had permitted consecutive sentences for gun charges stemming from a single incident committed during a drug crime or a crime of violence. Unfortunately, the law does not make most of its sentencing reforms retroactive, leaving thousands of people in prison. The First Step Implementation Act of 2021, which will soon go to the Senate floor for a vote, makes these key reforms retroactive and further expands the safety valve. Additionally, the House last year voted to address the collateral consequences of federal marijuana criminalization by passing the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act, which would, among provisions, provide for the expungement and resentencing of marijuana offenses. We urge you to support this year’s version of the MORE Act, H.R. 3617, in order to right the wrongs of decades of this criminalization.

Yet, these small, measured steps cannot adequately redress years of cruel and lengthy sentencing policies. To address fully the immense harms perpetrated by mandatory minimums and other sentencing practices, Congress must go beyond these incremental reforms and pass meaningful and expansive legislation that transforms the federal sentencing scheme. Such reform would reduce unnecessarily lengthy stays, enabling people to rebuild their lives, reducing the exorbitant costs of the prison system, and give redress to those serving unreasonably long sentences.

Mandatory minimum penalties have incurred devastating economic, societal, and human costs, destroying families and irreparably damaging communities of color. The penalties are lengthy, with almost no room for discretion or mercy. As one federal judge has declared, these are sentences that “no one – not even the prosecutors themselves – thinks are appropriate.”[23] President Biden has also recognized this destructive impact and has called for an end to federal mandatory minimum sentences and other harmful practices.[24] These sentences, and particularly those for drug offenses, have led to an explosion in the federal prison population with no attendant positive impact on crime deterrence or public safety. As we mark the 50th anniversary of the War on Drugs in 2021, we strongly urge Congress to take bold steps to address the damage wrought by mandatory minimum sentencing and transform our criminal-legal system into one that delivers true justice and equality.

[3] See, e.g., Samuels, Julie, & La Vigne, Nancy, & Thomson, Chelsea. “Next Steps in Federal Corrections Reform: Implementing and Building on the First Step Act.” Urban Institute. May 2019. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100230/next_steps_in_federal_corrections_reform_1.pdf; Travis, Jeremy, & Western, Bruce, & Redburn, Steve. “The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences.” Nat’l Research Council. 2014. Pg. 336. http://blogs.law.columbia.edu/praxis1313/files/2019/04/Chapter-13-NAS.pdf.

[4] “Statistics: Total Federal Inmates.” Federal Bureau of Prisons. Last updated June 10, 2021. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/population_statistics.jsp.

[6] “An Overview of Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System.” United States Sentencing Commission. Jul. 2017. Pg. 49. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/research-publications/2017/20170711_Mand-Min.pdf.

[9] “Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994: U.S. Dep’t of Justice Fact Sheet.” U.S. Dep’t of Justice. Oct. 24, 1994. https://www.ncjrs.gov/txtfiles/billfs.txt. The First Step Act of 2018 reduced this sentence to 25 years. Pub. L. No. 115-391 (2018).

[13] “Statistics: Inmate Offenses.” Federal Bureau of Prisons. Updated June 5, 2021. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp.

[16] Starr, Sonja B., and M. Marit Rehavi. “Racial Disparity in Federal Criminal Sentences.” University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. 2014. Pg. 1323. https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2413&context=articles.

[17] “Inmate Statistics.” Federal Bureau of Prisons. Updated June 5, 2021. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp. Hispanics make up 18.5% of the U.S. population, while Black people make up 13.4%. “United States QuickFacts.” U.S. Census Bureau. Last updated July 1, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219.

[18] “An Overview of Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System.” United States Sentencing Commission. Jul. 2017. Pg. 53. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/research-publications/2017/20170711_Mand-Min.pdf.

[19] “Mandatory Minimum Penalties for Drug Offenses in the Federal Criminal Justice System.” United States Sentencing Commission. Oct. 2017. Pg. 57. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/research-publications/2017/20170711_Mand-Min.pdf.

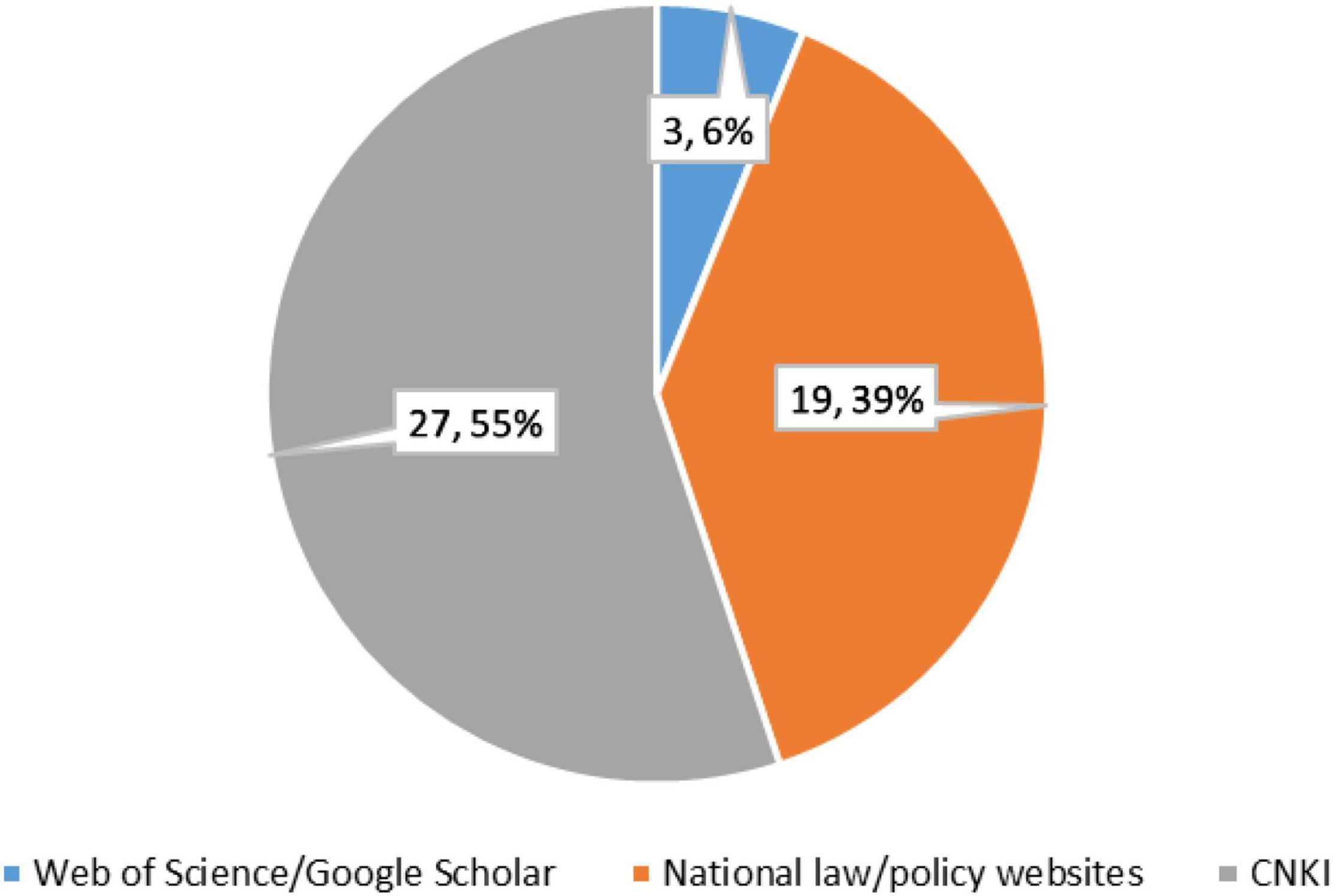

China’s spectacular economic growth has arguably been the most significant development in the twenty-first century thus far, with experts predicting a Chinese Century in which it will overtake the US as the world’s largest economy. Yet such growth, driven by exports and the consumption of China’s huge population, has far outstripped the protections in place for these consumers against bad practice and rogue traders, where China lags far behind developed countries, or, indeed, many developing countries around the world.

But growing dissatisfaction over levels of pollution in China could provide a much-needed opportunity to introduce new laws to help protect the rights of over a billion consumers in the world’s most populous country.

Between 1949 and 1979, ordinary people in China relied on the government to meet basic survival needs for food, clothing, and shelter. People could scarcely dream of consuming goods and services that went beyond basic necessities, let alone make claims regarding their consumer rights. Nowadays, thanks to Deng Xiaoping’s reform policies in the late 1970s and the policies that followed, the average citizen no longer struggles just to fulfill basic survival needs. Instead, they are increasingly attracted to luxury products, and many people can afford spacious houses and expensive cars.

The goal of Deng’s approach (known as ‘Socialism with Chinese Characteristics’) was to achieve rapid yet stable economic development. There were two crucial components of Deng’s reforms: achieving export-led growth and allowing some people to become rich. Deng used the term ‘Xiaokang society’ to offer a vision of Chinese society in which most people were moderately well off and belonged to the middle class. The export-led economy has dramatically shrunk the technological gap between China and developed countries and increased the size of the Chinese middle class.

Paradoxically for a country built on a rejection of bourgeois values, the Chinese government has increasingly encouraged ordinary people to enjoy access to ‘modern’ products and to spend time shopping. Western visitors are often astonished by the scale of the modern shopping malls that have sprung up over the last two decades. According to The Economist magazine, half of the world’s new shopping malls are in China, which is also the world’s biggest e-commerce market.

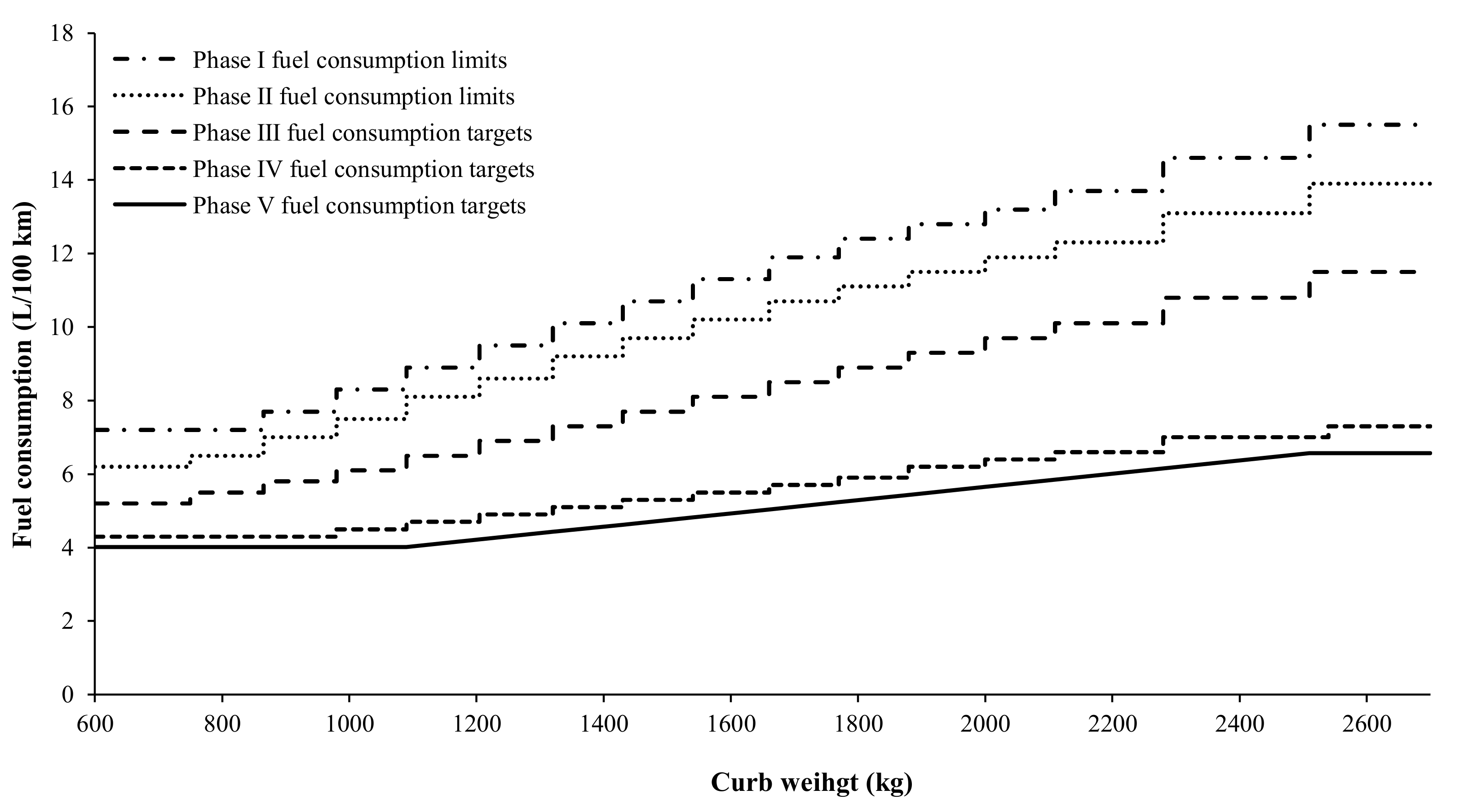

China’s policy to stimulate the market for consumer goods contrasts with the path taken by the Communist regime in the former Soviet Union, where the government suppressed popular access to Western products, which thus acquired an aura of ‘forbidden fruit’. The present Communist government of China has taken a strategic decision to improve access to products (both international and domestically produced) in the belief that it will make consumers satisfied, and, in view of the progress relative to the deprivations of past generations, less likely to press for political change. For example, in March 2014, the prime minister said that China should ‘fully tap the enormous consumption potential of more than a billion people’. Retail sales have been holding up well, with 11.6% growth in 2011, 12.1% in 2012, and 11.5% in 2013. (The Economist, China: Building the Dream, 19 April 2014).

The Communist government has taken a strategic decision to improve access to products in the belief that it will make consumers satisfied, and, in view of the progress relative to the deprivations of past generations, less likely to press for political change

There are limits, of course, to this ‘safety valve’ strategy, as fears over water quality, and, most conspicuously, air quality, raise questions about the viability of the new culture of the pursuit of affluence. It is predictable that concerns regarding these basic environmental necessities will be raised with greater urgency. Indeed, that has already happened with respect to the issue of air quality, and the government is set to conduct a major review of prices for the basic services of water and energy. So, while consumer preferences seem to be directed towards material goods such as cars and houses, pressure is increasing for this priority to change.

Although China’s ‘new rich’ have transformed the country into the biggest luxury goods market in the world, the vast majority of Chinese consumers want to avoid the problems that plague people in other developing nations — food adulteration, unsafe products, air and water pollution — while improving their access to basic goods and services.

The confidence of Chinese consumers in domestic products has been shaken by several food adulteration scandals, most notably the 2008 Chinese milk scandal in which milk powder adulterated with melamine affected an estimated 300,000 people. Six infants died from kidney stones and other kidney damage, and 60,000 babies were hospitalized. (The disbursement of the victims’ compensation fund remains a mystery.)

Little by little, health and safety breaches such as that seen in the milk scandal will undermine Chinese products and diminish consumer confidence. Citizens now have so much access to electronic media that it has become impossible for the government to suppress stories across the entire population of 1.35 billion people. Instead, it chose to tolerate, even to encourage, exposure of such scandals in the knowledge that people will come to know about them anyway, judging that the identification and prosecution of guilty parties will help to redirect the build-up of any resentment against the government itself.

Perhaps because the government cannot completely control informal dissemination of news by electronic media, it has tolerated free expression of critical points of view in relation to issues of consumer protection... up to a point, at least. At conferences and in academic institutions there can be remarkably frank criticisms of the status quo. At Wuhan University in March 2013, for example, many Chinese speakers were fiercely critical of financial institutions, including those controlled by the state. There is also vigorous debate within China regarding the country’s serious environmental problems. And government, in turn, is prepared to denounce failures of public administration. But direct criticism of government (as opposed to individual officials) is rare.

Perhaps because the government cannot completely control informal dissemination of news by electronic media, it has tolerated free expression of critical points of view in relation to issues of consumer protection... up to a point, at least.

Chinese consumers — taking for granted that they cannot collectively assert their rights to safety, education, redress, and a healthy environment — have largely employed individual strategies to address health and safety concerns. One strategy is to shun domestic products in favour of imported ones. Chinese consumers assume that consumer protections in developed countries function better than those in China, and therefore they are firmly convinced that the quality of products produced by developed countries is better than that of local products.

A second individual strategy is to lodge consumer complaints. Here, the role of theChinese Consumers’ Association (CCA), a large, quasi-governmental consumer organization with offices throughout China, is crucial. During 2013, CCA provided a significant public service by handling some quarter of a million cases. CCA’s 2013 annual summary reports that 92% of complaints were resolved. The result was 5 billion RMB (about $750 million) in refunds to consumers in 2012. While the complaint-resolution activities of CCA are impressive, it is important to point out that if a business does not cooperate with the CCA then it is extremely difficult for a case to be resolved. This results in a certain degree of cynicism among the public.

As a quasi-government institution, CCA is not only restrained by its institutional competences; it is also inhibited from activities that might damage the reputation of the government. CCA is supposed to be adequately funded by the State Administration for Industry & Commerce. However, CCA and its regional branches are constantly frustrated by insufficient funding necessary to organize teams of experts capable of lobbying for consumer rights.

Overall, the CCA’s complaint-handling activity does not amount to genuine consumer activism because CCA does not synthesize the complaints into policy themes nor mount campaigns for reform. Other than sporadic, localized consumer protests, the label of ‘activism’ is more accurately applied to the activities of environmental organizations, and it will be interesting to see to what extent consumer interests will move in that direction, for example, regarding water quality or measures to reduce pollution.

Domestically, there is relatively little collaboration as yet between ‘consumer activists’ and people pursuing other causes such as environmentalism. This may be because of the potential tensions between environmental and consumer organizations concerning the increased cost of consumer goods associated with measures to reduce pollution.

Paradoxically, the gravity of the environmental problems faced by China and the fact that incomes have risen so dramatically in recent years may lead to an acceptance by consumers of the need for corrective measures, even ones that increase prices. But assistance may need to be offered to the poorest in society to cope with the inevitable price rises. In any event, concerns over pollution in China are now so pressing as to make it highly likely that common cause between consumer and environmental activists will be made at some level in the near future.

Concerns over pollution in China are now so pressing as to make it highly likely that common cause between consumer and environmental activists will be made in the near future

Chinese consumer organizations are in touch with evolving international debates regarding consumer rights and consumer policy. CCA is a member of Consumers International, and the organization has easy access to influential consumer bodies in Hong Kong and Taiwan. However, CCA has few opportunities to develop the approaches adopted by these agencies into policy in China, as its terms of reference are restricted to dispute resolution.

A recent development of some significance is the provision for class action lawsuits under the recently enacted Consumer Protection Law, which came into force on 15 March 2014, or World Consumer Rights Day, known as san yao wu in China. For the moment, however, only government-affiliated consumer associations, such as CCA, are allowed to launch such lawsuits. The extent to which this change was brought about by ‘activism’ or by the damage inflicted on the government’s reputation by incidents such as food contamination is open to debate. The answer is probably that generalized discontent among the public rather than identifiable activists provided the impetus for change.

In sum, most activity on behalf of consumers in China cannot be described as ‘activism’ in the sense the term is used in most countries. Rather, the government controls most aspects of consumer affairs, restricting its activity to assistance in complaint resolution. The environmental challenges facing the country may change this situation. Environmental problems cannot be ignored or suppressed from the Chinese public, since they assault the senses in any big city. Consumer and environmental concerns are converging, and both suggest the need for citizen pressure for remedial action.

Chairwoman Jackson Lee, Ranking Member Biggs, and members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to submit a statement for the record for this critical hearing. On behalf of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, a coalition charged by its diverse membership of more than 220 national organizations to promote and protect civil and human rights in the United States, I write to underscore the critical need for sentencing reform and urge the Subcommittee and all of Congress to heed President Biden’s call for the end of mandatory minimums and other overly-punitive policies that undermine the very foundation of justice in our country.

Over the past five decades, U.S. criminal-legal policies have driven an increase in incarceration rates that is unprecedented in this country’s history and unmatched globally: the United States incarcerates more people than any other country in the world, with more than 2 million people currently incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails.[1] Over-criminalization and over-incarceration have devastating impacts on those ensnared in the criminal-legal system and on their families, do not produce any proportional increase in public safety, and disproportionately harm low-income communities and communities of color. In particular, mandatory minimum penalties are a key driver of the burgeoning prison population, and eliminating them is crucial to any sentencing reform legislation. The Leadership Conference is categorically opposed to mandatory minimums sentences, and urges Congress to take steps toward repairing the damage wrought by these penalties by ending blanket policies that do not allow for judicial discretion and promoting alternatives to arrest and incarceration.

Since the mid-20th century, Congress has expanded its use of mandatory minimum penalties by broadening it to include different offenses and lengthening the mandatory minimum sentences.[2] The proliferation of the use of mandatory minimum sentences has fueled skyrocketing prison populations.[3] The federal prison population has increased from approximately 25,000 in FY1980 to nearly 152,894 today.[4] For each year between 1980 and 2013, federal prisons added almost 6,000 more inmates than the previous year.[5] As of 2016, 55% of the federal prison population was comprised of those who had been sentenced under a mandatory minimum provision.[6] While drops in prosecutions and in the severity of sentences for drug-related crime, as well as releases due to the COVID-19 pandemic, have led to a decline in the federal prison population in recent years, by and large these piecemeal changes are insufficient to reverse nearly forty years of explosive growth.[7] The Bureau of Prisons’ (BOP) budget has grown in tandem: the President’s FY22 budget request for BOP is $8 billion, which accounts for nearly a quarter of the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) entire budget.[8]

Draconian drug laws and their resulting enforcement are the source of much of this growth. Under the banner of the War on Drugs, the Reagan administration imposed particularly harsh mandatory minimum penalties for drug offenses under the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 and dedicated more than a billion dollars ($2.3 billion in today’s dollars) to law enforcement efforts to increase drug arrests. The Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 (known colloquially as the 1994 Crime Bill) instituted a “three strikes” penalty that mandated a life sentence for anyone convicted of certain prior drug or violent felonies and incentivized states to adopt similar ‘tough-on-crime’ policies.[9] The “arrest-first” policies of the 1980s and ‘90s led to a surge in drug arrests, with a particularly large impact on cannabis arrests,[10] and an attendant use of long mandatory minimum sentences that caused the federal prison population to explode. The Urban Institute has found that increases in expected time served for drug offenses was the largest contributor to growth in the federal prison population between 1998 and 2010.[11] The Charles Colson Task Force on Federal Corrections, a Congressionally-mandated, bipartisan organization, attributes the growth both to the number of people admitted to prison for drug crimes as well as to the increased length of their sentences.[12] Currently, people convicted of drug offenses make up 46.3 percent of the BOP population.[13]

Yet, despite the dramatic uptick in incarceration, there is no indication that these sentences deter crime, protect public safety, or decrease drug use or trafficking. Increasing the severity of punishment has little impact on crime deterrence, and studies of federal drug laws show no significant relationship between drug imprisonment rates and drug use or recidivism.[14] The punishment-based approach to the War on Drugs, with its dramatic increase in the use of mandatory minimums — and corresponding increase in incarceration — has produced lasting harm in communities across the country while having little effect on actual drug use or crime. Unfortunately, the myth that punishment and harsh mandatory minimums will reduce drug use and crime persists in real and consequential ways: just this past April, Congress extended the temporary “class wide” emergency scheduling of fentanyl-related substances, which will exacerbate untenable federal sentencing trends and give rise to harsh mandatory minimum penalties for offenses involving fentanyl analogues.[15] Statistics about the growth in mass incarceration due to mandatory minimums, combined with data showing they have no positive effect on public safety, illustrate the harmful impact of these sentences on prison growth and the need to turn away from such antiquated “tough on crime” policies.

Mandatory minimums also eliminate judicial discretion, preventing judges from tailoring punishment to a particular defendant by taking into account an individual’s background and the circumstances of his or her offenses when determining his or her sentence. Mandatory minimums instead place more power in the hands of prosecutors and their charging decisions, which is particularly concerning given that prosecutors are more likely to charge Black people with a crime that carries a mandatory minimum than a White person.[16] Mass incarceration as a whole has had a markedly disproportionate impact on communities of color. Today, BOP reports that 38 percent of its current prison population is Black and 30.2 percent is Hispanic, an enormous disparity given that both groups represent only about one third of the nation’s population combined.[17] These disparities are also reflected in mandatory minimum penalties. In a 2017 review of mandatory minimum sentencing policies, the U.S. Sentencing Commission found that Black people in BOP custody were more likely to have been convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum penalty than any other group.[18] Hispanic and Black people accounted for a majority of those convicted with an offense carrying a drug mandatory minimum,[19] despite the fact that White and Black people use illicit substances at roughly the same rate, and Hispanic people use such substances at a lower rate.[20] The study also showed that Black people were the least likely to receive relief from mandatory minimum sentences compared to White and Hispanic people.[21] Finally, the review found racial disparities in convictions of a federal offense subject to a mandatory minimum penalty: 73.2 percent of Black people convicted of a federal offense received a mandatory minimum sentence, compared to 70 percent of White people and 46.9 percent of Hispanic people.[22] It is clear that mandatory minimums create stark racial disparities in federal sentencing.

Congress has made some progress toward addressing the harms of mandatory minimums. In 2010, Congress passed the Fair Sentencing Act (FSA), which reduced the disparities between the mandatory penalties for crack and powder cocaine from 100:1 to 18:1. Building on this legislation, the First Step Act of 2018 made necessary, though modest, improvements to the federal sentencing scheme by making the FSA retroactive and through expanding the federal safety valve, which permits a sentencing court to disregard minimum sentences for low-level, nonviolent defendants. Under this provision, judges have discretion to make a person eligible for the safety valve in cases where the seriousness of his or her record is over-represented, or it is unlikely he or she would commit other crimes. The law also reformed and reduced the unfair three-strike mandatory minimum sentence from life to 25 years. The First Step Act further eliminated 924(c) stacking, which had permitted consecutive sentences for gun charges stemming from a single incident committed during a drug crime or a crime of violence. Unfortunately, the law does not make most of its sentencing reforms retroactive, leaving thousands of people in prison. The First Step Implementation Act of 2021, which will soon go to the Senate floor for a vote, makes these key reforms retroactive and further expands the safety valve. Additionally, the House last year voted to address the collateral consequences of federal marijuana criminalization by passing the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement (MORE) Act, which would, among provisions, provide for the expungement and resentencing of marijuana offenses. We urge you to support this year’s version of the MORE Act, H.R. 3617, in order to right the wrongs of decades of this criminalization.

Yet, these small, measured steps cannot adequately redress years of cruel and lengthy sentencing policies. To address fully the immense harms perpetrated by mandatory minimums and other sentencing practices, Congress must go beyond these incremental reforms and pass meaningful and expansive legislation that transforms the federal sentencing scheme. Such reform would reduce unnecessarily lengthy stays, enabling people to rebuild their lives, reducing the exorbitant costs of the prison system, and give redress to those serving unreasonably long sentences.

Mandatory minimum penalties have incurred devastating economic, societal, and human costs, destroying families and irreparably damaging communities of color. The penalties are lengthy, with almost no room for discretion or mercy. As one federal judge has declared, these are sentences that “no one – not even the prosecutors themselves – thinks are appropriate.”[23] President Biden has also recognized this destructive impact and has called for an end to federal mandatory minimum sentences and other harmful practices.[24] These sentences, and particularly those for drug offenses, have led to an explosion in the federal prison population with no attendant positive impact on crime deterrence or public safety. As we mark the 50th anniversary of the War on Drugs in 2021, we strongly urge Congress to take bold steps to address the damage wrought by mandatory minimum sentencing and transform our criminal-legal system into one that delivers true justice and equality.

[3] See, e.g., Samuels, Julie, & La Vigne, Nancy, & Thomson, Chelsea. “Next Steps in Federal Corrections Reform: Implementing and Building on the First Step Act.” Urban Institute. May 2019. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/100230/next_steps_in_federal_corrections_reform_1.pdf; Travis, Jeremy, & Western, Bruce, & Redburn, Steve. “The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences.” Nat’l Research Council. 2014. Pg. 336. http://blogs.law.columbia.edu/praxis1313/files/2019/04/Chapter-13-NAS.pdf.

[4] “Statistics: Total Federal Inmates.” Federal Bureau of Prisons. Last updated June 10, 2021. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/population_statistics.jsp.

[6] “An Overview of Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System.” United States Sentencing Commission. Jul. 2017. Pg. 49. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/research-publications/2017/20170711_Mand-Min.pdf.

[9] “Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994: U.S. Dep’t of Justice Fact Sheet.” U.S. Dep’t of Justice. Oct. 24, 1994. https://www.ncjrs.gov/txtfiles/billfs.txt. The First Step Act of 2018 reduced this sentence to 25 years. Pub. L. No. 115-391 (2018).

[13] “Statistics: Inmate Offenses.” Federal Bureau of Prisons. Updated June 5, 2021. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_offenses.jsp.

[16] Starr, Sonja B., and M. Marit Rehavi. “Racial Disparity in Federal Criminal Sentences.” University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. 2014. Pg. 1323. https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2413&context=articles.

[17] “Inmate Statistics.” Federal Bureau of Prisons. Updated June 5, 2021. https://www.bop.gov/about/statistics/statistics_inmate_race.jsp. Hispanics make up 18.5% of the U.S. population, while Black people make up 13.4%. “United States QuickFacts.” U.S. Census Bureau. Last updated July 1, 2019. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219.

[18] “An Overview of Mandatory Minimum Penalties in the Federal Criminal Justice System.” United States Sentencing Commission. Jul. 2017. Pg. 53. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/research-publications/2017/20170711_Mand-Min.pdf.

[19] “Mandatory Minimum Penalties for Drug Offenses in the Federal Criminal Justice System.” United States Sentencing Commission. Oct. 2017. Pg. 57. https://www.ussc.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/research-and-publications/research-publications/2017/20170711_Mand-Min.pdf.

This website is using a security service to protect itself from online attacks. The action you just performed triggered the security solution. There are several actions that could trigger this block including submitting a certain word or phrase, a SQL command or malformed data.

Is justice best served by having legislatures assign fixed penalties to each crime? Or should legislatures leave judges more or less free to tailor sentences to the aggravating and mitigating facts of each criminal case within a defined range?

The proliferation in recent decades of mandatory minimum penalties for federal crimes, along with the tremendous increase in the prison population, has forced those concerned with criminal justice in America to reconsider this age-old question. The Supreme Court of the United States has upheld lengthy mandatory terms of imprisonment over the challenge that they violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishments.[1] The question remains, however, whether mandatory minimums are sound criminal justice policy.

Today, public officials on both sides of the aisle support amending the federal mandatory minimum sentencing laws. Two bills with bipartisan support are currently under consideration. Senators Patrick Leahy (D–VT) and Rand Paul (R–KY) have introduced the Justice Safety Valve Act of 2013,[2] which would apply to all federal mandatory minimums. Senators Dick Durbin (D–IL) and Mike Lee (R–UT) have introduced the Smarter Sentencing Act, which would apply to federal mandatory minimums for only drug offenses.[3]

In what follows, this paper will explain how mandatory minimums emerged in the modern era, summarize the policy arguments for and against mandatory minimums, and evaluate both the Justice Safety Valve Act and the Smarter Sentencing Act. The bottom line is this: Each proposal might be a valuable step forward in criminal justice policy, but it is difficult to predict the precise impact that each one would have. This much, however, appears likely: The Smarter Sentencing Act is narrowly tailored to address one of the most pressing problems with mandatory minimums: severe sentences for relatively minor drug possession crimes.[4]

For most of the 19th and 20th centuries, federal trial judges had virtually unlimited sentencing discretion.[5] In the 1960s and 1970s, influential members of the legal establishment criticized that practice,[6] concluding that that unrestrained discretion gave rise to well-documented sentencing disparities in factually similar cases.[7] Over time, that scholarship paved the way for Congress to modify the federal sentencing process through the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984.[8] That law did not withdraw all sentencing discretion from district courts; it did, however, establish the United States Sentencing Commission and directed it to promulgate Sentencing Guidelines that would regulate and channel the discretion that remained.[9]

Congress also decided to eliminate the courts’ discretion to exercise leniency in some instances by requiring courts to impose a mandatory minimum sentence for certain types of crimes. For example, Congress enacted the Armed Career Criminal Act[10] in 1984 as part of the same law that included the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984.[11] The Armed Career Criminal Act demands that a district court sentence to a minimum 15-year term of imprisonment anyone who is convicted of being a felon in possession of a firearm if he has three prior convictions for “a violent felony or a serious drug offense.”[12] Two years later, concerned by the emergence of a new form of cocaine colloquially known as “crack,” Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986,[13] which imposes mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment for violations of the federal controlled substances laws.[14]

Congress could have allowed the U.S. Sentencing Commission to devise appropriate punishment for those offenses, at least as an initial matter. Instead, Congress forged ahead and preempted the commission by decreeing that offenders should serve defined mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment when convicted of those crimes.[15]

District courts may depart downward from those mandatory minimum sentences only in limited circumstances. For example, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 has two exceptions to the mandatory minimum sentencing requirement. The first occurs if a defendant cooperates with the government and the government files a motion for a downward departure from the statutory minimum.[16] Absent such a motion, the district court cannot reduce a defendant’s sentence based on that exception.[17] The second exception involves the so-called safety valve that allows judges to avoid applying mandatory minimums, even absent substantial assistance.[18] The safety valve, however, has a limited scope: It applies only to sentences imposed for nonviolent drug offenses[19] where the offender meets specific criteria relating to criminal history, violence, lack of injury to others, and leadership.[20] Otherwise, a district court must impose the sentence fixed by the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. With regard to the Armed Career Criminal Act, no federal law authorizes a district court to impose a term of imprisonment less than the one required by that statute.

The Armed Career Criminal Act and the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 are the two principal modern federal statutes requiring mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment—but they are by no means the only ones. Mandatory minimums have proliferated and have increased in severity. Since 1991, the number of mandatory minimums has more than doubled.[21] Entirely new types of offenses have become subject to mandatory minimums, from child pornography to identity theft.[22] During that period, the percentage of offenders convicted of violating a statute carrying a mandatory minimum of 10 years increased from 34.4 percent to 40.7 percent.[23]

There are powerful arguments on each side of this debate. The next two sections summarize the arguments pro and con on mandatory minimum sentences as each side of that debate would make its case.[24]

The Assault on Mandatory Minimum Sentences.Mandatory minimum sentences have not eliminated sentencing disparities because they have not eliminated sentencing discretion; they have merely shifted that discretion from judges to prosecutors.[25] Judges may have to impose whatever punishment the law requires, but prosecutors are under no comparable obligation to charge a defendant with violating a law carrying a mandatory minimum penalty.[26] As a practical matter, prosecutors have unreviewable discretion over what charges to bring, including whether to charge a violation of a law with a mandatory minimum sentence, and over whether to engage in plea bargaining, including whether to trade away a count that includes such a law. Moreover, even if a prosecutor brings such charges against a defendant, the prosecutor has unreviewable discretion whether to ask the district court to reduce a defendant’s sentence due to his “substantial assistance” to the government.[27]

What is more, critics say, unbridled prosecutorial discretion is a greater evil than unlimited judicial discretion. Prosecutors are not trained at sentencing and do not exercise discretion in a transparent way.[28] Critics also claim that prosecutors, who stand to gain professionally from successful convictions under mandatory minimums, do not have sufficient incentive to exercise their discretion responsibly.[29]

Indeed, nowhere else in the criminal justice system does the law vest authority in one party to a dispute to decide what should be the appropriate remedy. That decision always rests in the hands of a jury, which must make whatever findings are necessary for a punishment to be imposed, or the judge, who must enter the judgment of conviction that authorizes the correctional system to punish the now-convicted defendant.[30]

Furthermore, they contend, mandatory minimum sentences do not reduce crime. As University of Minnesota Law Professor Michael Tonry has concluded, “the weight of the evidence clearly shows that enactment of mandatory penalties has either no demonstrable marginal deterrent effects or short-term effects that rapidly waste away.”[31] Nor is it clear that mandatory minimum sentences reduce crime through incapacitation. In many drug operations, if a low-level offender is incapacitated, another may quickly take his place through what is known as the “replacement effect.”[32] In drug cases, mandatory minimum sentences are also often insensitive to factors that could make incapacitation more effective, such as prior criminal history.[33]

In theory, mandatory minimum sentences enable the government to “move up the chain” of large drug operations by using the assistance of convicted lower-level offenders against senior offenders. The government can reward an offender’s cooperation by moving in district court for a reduction of the offender’s term of imprisonment below whatever term is required by law.[34] In reality, however, critics argue that the value of that leverage is overstated. The rate of cooperation in cases involving mandatory minimums is comparable to the average rate in all federal cases.[35]

Further, only certain defendants in cases involving organized crime—those who are closest to the top of the pyramid—will be able to render substantial assistance.[36] The result is that sentencing reductions go to serious offenders rather than to small-scale underlings. The practice of affording sentence concessions to defendants who assist the government is entrenched in American law, but the quantity-driven drug mandatory minimums are uniquely problematic because they can render each low-level co-conspirator responsible for the same quantity of drugs as the kingpin.[37]

Statutes imposing mandatory minimum sentences result in arbitrary and severe punishments that undermine the public’s faith in America’s criminal justice system. Consider the effect of those provisions in the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. Drug offenses, which make up a significant proportion of mandatory minimums, can give rise to arbitrary, severe punishments.[38] The difference between a drug quantity that triggers a mandatory minimum and one that does not will often produce a “cliff effect.”[39] While someone with 0.9 gram of LSD might not spend much time incarcerated, another fraction of a gram will result in five years behind bars.

In fact, it is easy to find examples of unduly harsh mandatory minimums for drug offenses. A financially desperate single mother of four with no criminal history was paid $100 by a complete stranger to mail a package that, unbeknownst to her, contained 232 grams of crack cocaine. For that act alone, she received a sentence of 10 years in prison even though the sentencing judge felt that this punishment was completely unjust and irrational.[40]

In some cases, mandatory minimums have been perceived as being so disproportionate to a person’s culpability that the offender has altogether escaped punishment. Florida Judge Richard Tombrink “nullified” the 25-year mandatory sentence of a man who possessed (without an intent to distribute) hydrocodone pills.[41] Juries also have the power to nullify by acquitting someone they would otherwise have convicted if not for the disproportionately harsh sentence. Although defendants cannot demand that the trial judge explicitly instruct the jury that it has the power to nullify, in mandatory contexts, a judge troubled by the length of the sentence a defendant must receive for a conviction can allow the jury to learn what those penalties are in the hope that the jury exercises this power sua sponte.[42]

Finally, critics maintain that mandatory minimum sentences are not cost-effective. The certainty of arrest, prosecution, conviction, and punishment has a greater deterrent effect than the severity of punishment. If a one-year sentence for a crime has the same deterrent effect as a five-year sentence, the additional four years of imprisonment inflict unnecessary pain on the offender being incarcerated and, to borrow from economics, impose a “dead weight” loss on society. Mandatory minimum sentences, therefore, waste scarce criminal justice resources.

The Defense of Mandatory Minimums.On the other hand, a number of parties defend the use of mandatory minimum terms of imprisonment. They argue that mandatory minimum sentences reflect a societal judgment that certain offenses demand a specified minimum sanction and thereby ensure that anyone who commits such a crime cannot avoid a just punishment.

A nation of more than 300 million people will necessarily have a tremendous diversity of views as to the heinousness of the conduct proscribed by today’s penal codes, and a bench with hundreds of federal district court judges will reflect that diversity. The decision as to what penalty should be imposed on a category of offenders requires consideration of the range of penological justifications for punishment, such as retribution, deterrence, incapacitation, education, and rehabilitation. Legislatures are better positioned than judges to make those types of judgments,[43] and Americans trust legislatures with the authority to make the moral and empirical decisions about how severely forbidden conduct should be sanctioned. Accordingly, having Congress specify the minimum penalty for a specific crime or category of offenses is entirely consistent with the proper functioning of the legislature in the criminal justice processes.

Mandatory minimum sentences eliminate the dishonesty that characterized sentencing for the majority of the 20th century. For most of that period, Congress vested district courts with complete discretion to select the appropriate period of confinement for an offender while also granting parole officials the authority to decide precisely whether and when to release an inmate before the completion of his sentence.

That division of authority created the inaccurate impression that the public action of the judge at sentencing fixed the offender’s punishment while actually leaving that decision to the judgment of parole officials who act outside of the view of the public. At the same time, Congress could escape responsibility for making the moral judgments necessary to decide exactly how much punishment should be inflicted upon an individual by passing that responsibility off to parties who are not politically accountable for their actions. The entire process reflected dishonesty and generated cynicism, which corrodes the professional and public respect necessary for the criminal justice system to be deemed a morally defensible exercise of governmental power.

Mandatory minimum sentences also address two widely acknowledged problems with the criminal justice system: sentencing disparity and unduly lenient sentences. Mandatory minimums guarantee that sentences are uniform throughout the federal system and ensure that individuals are punished commensurate with their moral culpability by hitching the sentence to the crime, not the person.[44]

In fact, the need to use mandatory minimums as a means of addressing sentencing variances has become more pressing in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2005 decision in United States v. Booker.[45] Booker excised provisions of the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 that had made the Sentencing Guidelines binding upon federal judges.[46] The result, unfortunately, has been a return to the type of inconsistency that existed before that statute became law. According to the Department of Justice, Bookerhas precipitated a return to unbridled judicial discretion: “[For] offenses for which there are no mandatory minimums, sentencing decisions have become largely unconstrained.”[47] Booker therefore threatens to resurrect the sentencing disparities that, 30 years ago, prompted Congress to enact the Sentencing Reform Act. Mandatory minimum sentences may be the only way to eliminate that disparity today.

Mandatory minimum sentences also prevent crime because certain and severe punishment inevitably will have a deterrent effect.[48] Locking up offenders also incapacitates them for the term of their imprisonment and thereby protects the public.[49] In fact, where the chance of detection is low, as it is in the case of most drug offenses, reliance on fixed, lengthy prison sentences is preferable to a discretionary sentencing structure because mandatory sentences enable communities to conserve scarce enforcement resources without losing any deterrent benefit.[50]

Finally, the available evidence supports those conclusions. The 1990s witnessed a significant drop in crime across all categories of offenses,[51] and the mandatory minimum sentences adopted in the 1980s contributed to that decline.[52]

Moreover, mandatory minimums are an important law enforcement tool. They supply the police and prosecutors with the leverage necessary to secure the cooperation and testimony of low-level offenders against their more senior confederates.[53] The evidence shows that mandatory minimums, together with the Sentencing Guidelines promulgated by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, have

8613371530291

8613371530291