wire rope capacity formula quotation

While it is virtually impossible to calculate the precise length of wire rope that can be spooled on a reel or drum, the following provides a sufficiently close approximation.

* This formula is based on uniform rope winding on the reel. It will not give correct results if the winding is non-uniform. The formula also assumes that there will be the same number of wraps in each layer. While this is not strictly correct, there is no appreciable error in the result unless the traverse of the reel is quite small relative to the flange diameter (“H”).

** The values given for “K” factors take normal rope oversize into account. Clearance (“x”) should be about 2 inches unless rope-end fittings require more.

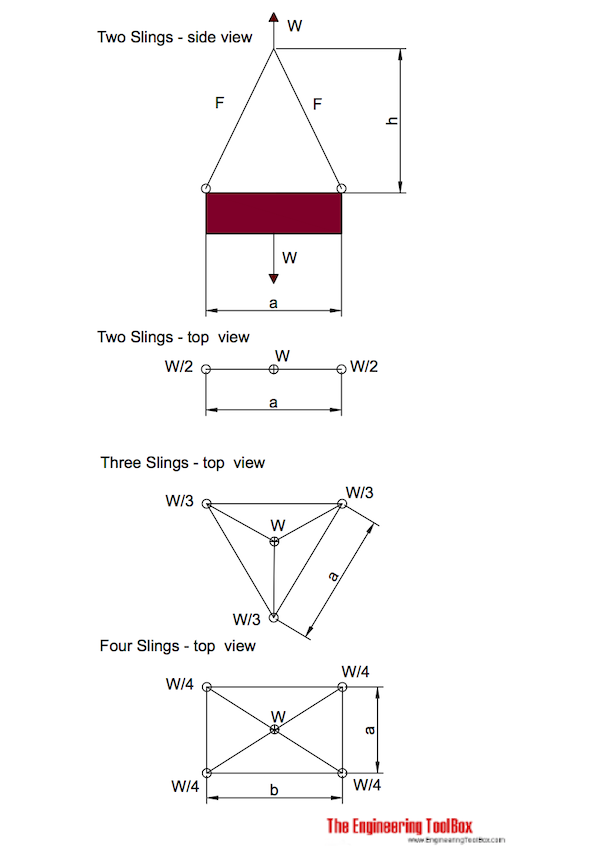

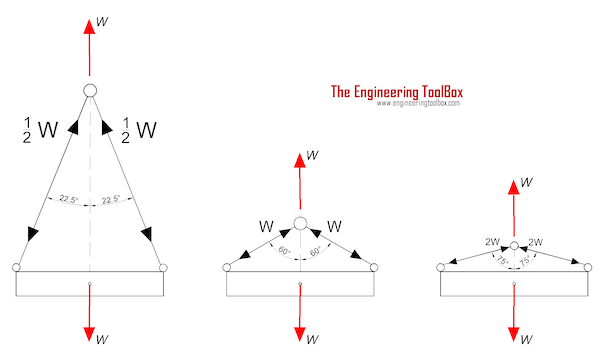

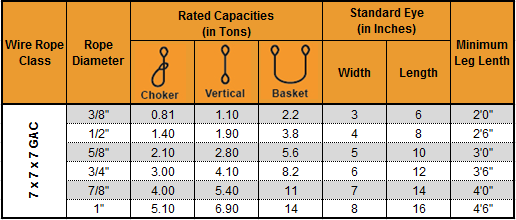

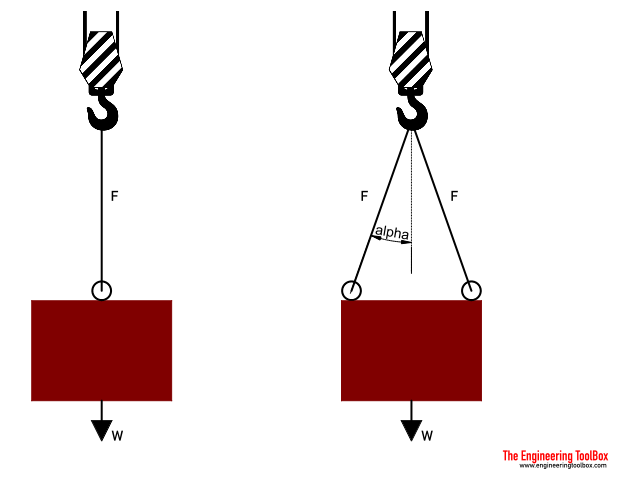

If you are performing calculations involving the load of bridles and basket hitches, it’s important to use a wire rope sling capacity chart and also remember that as a reduction in the horizontal angle of the sling occurs the load imposed upon each leg increases. With bridles consisting of three or more legs, the horizontal angle is measured in the same manner as it is for horizontal sling angles consisting of two legged hitches. Different angles may result if a bridle consists of different leg lengths. The load supported by each leg must be determined based on the location of the center of gravity of the lift in the position of the slings.

At Kennedy Wire Rope & Sling Co., Inc., we provide high quality wire rope sling components and can help you determine the capacity of your wire rope sling arrangement.

By making an adjustment to the rated capacity of a choker hitch degrees with the body of the sling used in the choke, the rated capacity is reduced. Choker rated capacity tables indicate this reduction. The angle the choke must also be considered when determining reductions in rated capacity.

The standard choke angle is about 135 degrees when a load is hanging free. However, using a choker hitch to lift internal load can produce a significant bend at the choke. It’s important to reduce a hitches rated capacity when it is used at an angle smaller than 120 degrees. As is evident from a wire rope sling capacity chart, the rated capacity of a wire rope sling must be adjusted when using a choker hitch to turn, shifts, or control the load. The rated capacity must also be adjusted when, in a multi-leg lift, the pull is against the choke.

Using choker hitches at angles of 135° or greater is not recommended due to the instability produced with this arrangement. In addition to consulting with a wire rope sling capacity chart, considerable care should also be taken to ensure that the choke angle is determined and applied as accurately as possible.

Rope strength is a misunderstood metric. One boater will talk about tensile strength, while the other will talk about working load. Both of these are important measurements, and it’s worth learning how to measure and understand them. Each of these measurements has different uses, and here we’re going to give a brief overview of what’s what. Here’s all you need to know about rope strength.

Each type of line, natural fiber, synthetic and wire rope, have different breaking strengths and safe working loads. Natural breaking strength of manila line is the standard against which other lines are compared. Synthetic lines have been assigned “comparison factors” against which they are compared to manila line. The basic breaking strength factor for manila line is found by multiplying the square of the circumference of the line by 900 lbs.

When you purchase line you will buy it by its diameter. However, for purposes of the USCG license exams, all lines must be measured by circumference. To convert use the following formula.

As an example, if you had a piece of ½” manila line and wanted to find the breaking strength, you would first calculate the circumference. (.5 X 3.14 = 1.57) Then using the formula above:

To calculate the breaking strength of synthetic lines you need to add one more factor. As mentioned above, a comparison factor has been developed to compare the breaking strength of synthetics over manila. Since synthetics are stronger than manila an additional multiplication step is added to the formula above.

Using the example above, letÂ’s find the breaking strength of a piece of ½” nylon line. First, convert the diameter to the circumference as we did above and then write the formula including the extra comparison factor step.

Just being able to calculate breaking strength doesn’t give one a safety margin. The breaking strength formula was developed on the average breaking strength of a new line under laboratory conditions. Without straining the line until it parts, you don’t know if that particular piece of line was above average or below average. For more information, we have discussed the safe working load of ropes made of different materials in this article here.

It’s very important to understand the fundamental differences between the tensile strength of a rope, and a rope’s working load. Both terms refer to rope strength but they’re not the same measurement.

A rope’s tensile strength is the measure of a brand-new rope’s breaking point tested under strict laboratory-controlled conditions. These tests are done by incrementally increasing the load that a rope is expected to carry, until the rope breaks. Rather than adding weight to a line, the test is performed by wrapping the rope around two capstans that slowly turn the rope, adding increasing tension until the rope fails. This test will be repeated on numerous ropes, and an average will be taken. Note that all of these tests will use the ASTM test method D-6268.

The average number will be quoted as the rope’s tensile strength. However, a manufacturer may also test a rope’s minimum tensile strength. This number is often used instead. A rope’s minimum tensile strength is calculated in the same way, but it takes the average strength rating and reduces it by 20%.

A rope’s working load is a different measurement altogether. It’s determined by taking the tensile strength rating and dividing it accordingly, making a figure that’s more in-line with an appropriate maximum load, taking factors such as construction, weave, and rope longevity into the mix as well. A large number of variables will determine the maximum working load of a rope, including the age and condition of the rope too. It’s a complicated equation (as demonstrated above) and if math isn’t your strong point, it’s best left to professionals.

However, if you want to make an educated guess at the recommended working load of a rope, it usually falls between 15% and 25% of the line’s tensile strength rating. It’s a lotlower than you’d think. There are some exceptions, and different construction methods yield different results. For example, a Nylon rope braided with certain fibers may have a stronger working load than a rope twisted out of natural fibers.

For safety purposes, always refer to the information issued by your rope’s manufacturer, and pay close attention to the working load and don’t exceed it. Safety first! Always.

If you’re a regular sailor, climber, or arborist, or just have a keen interest in knot-tying, be warned! Every knot that you tie will reduce your rope’s overall tensile strength. Some knots aren’t particularly damaging, while others can be devastating. A good rule of thumb is to accept the fact that a tied knot will reduce your rope’s tensile strength by around 50%. That’s an extreme figure, sure, but when it comes to hauling critical loads, why take chances?

Knots are unavoidable: they’re useful, practical, and strong. Splices are the same. They both degrade a rope’s strength. They do this because a slight distortion of a rope will cause certain parts of the rope (namely the outer strands) to carry more weight than others (the inner strand). In some cases, the outer strands end up carrying all the weight while the inner strands carry none of it! This isn’t ideal, as you can imagine.

Some knots cause certain fibers to become compressed, and others stretched. When combined together, all of these issues can have a substantial effect on a rope’s ability to carry loads.

Naturally, it’s not always as drastic as strength loss of 50% or more. Some knots aren’t that damaging, some loads aren’t significant enough to cause stress, and some rope materials, such as polypropylene, Dyneema, and other modern fibers, are more resilient than others. Just keep in mind that any knots or splices will reduce your rope’s operations life span. And that’s before we talk about other factors such as the weather or your rope care regime…

Rated load based on pin diameter no larger than one half the natural eye length or not less than the nominal sling diameter. Basket hitch capacity based on minimum D/d ratio of 25/1. For choker hitch, the angle of choke shall be 120 degrees or greater. For sling angles other than those shown, use the rated load for the next lower angle or a qualified person shall calculate the rated load. Horizontal sling angles of less than 30 degrees are not recommended. The capacity of a bridle at a 30 degree horizontal is same as single vertical leg.

There will always be a loss of sling capacity whenever a sling bends around another object. The D/d Ratio aids in determining the sling’s capacity reduction, allowing you to make corrections before continuing a lift.

Specific to polyester round slings, it varies among manufacturers, but usually, they recommend minimum hardware diameters to protect the inner core yarns. The illustration above provides an example of minimum shackle size requirements when using round slings. Bear in mind that round slings are more negatively affected by users bunching up the sling and not allowing the yarns to spread out properly and disperse the load when in a choker configuration.

Using choker hitches may save headroom; however, even following manufacturer-specified hardware diameter, the sling’s rated capacity reduces to 75% of the listed vertical rating. Failing to understand this relationship often results in overloading the sling.

While all slings lose capacity when they are bent beyond a certain point, basket hitch ratings are based on a minimum diameter and the capacity must be reduced when the sling’s D/d falls below the minimum D/d ratio. Keep in mind, a true basket is one in which the legs of the sling remain at a 90-degree vertical angle.

In the rental business, we often see rigging equipment damaged due to sling capacity reduction being ignored or miscalculated. Often, the equipment is damaged beyond repair, leading to unsafe rigging practices and additional repair or replacement costs for our customers. This is why it’s imperative to understand and abide by D/d Ratio specifications.

In any cable or wire rope application, stretch may be a concern. There are two forms of stretch in cable and wire rope: Structural Stretch and Elastic Stretch.

Structural stretch is the lengthening of the lay in the construction of cable and wire rope as the individual wires adjust under load. Structural stretch in Loos and Company products is less than 1% of the total cable length. This form of stretch can be completely removed by applying a cable or wire rope prestretching operation prior to shipment.

Elastic stretch is the actual physical elongation of the individual wires under load. The elastic stretch can be calculated by using the following formula*:

Sheaves facilitate the smooth and safe operation of overhead crane hoists. Damaged sheaves can wear ropes prematurely and cause other dangerous hazards, such as binding wire rope. Konecranes technicians are trained to identify and correct problems with sheaves and other parts of hoisting equipment.

Sheaves carrying ropes which can be momentarily unloaded shall be provided with close-fitting guards or other suitable devices to guide the rope back into the groove when the load is applied again.

The sheaves in the bottom block shall be equipped with close-fitting guards that will prevent ropes from becoming fouled when the block is lying on the ground with ropes loose.

In using hoisting ropes, the crane manufacturer"s recommendation shall be followed. The rated load divided by the number of parts of rope shall not exceed 20 percent of the nominal breaking strength of the rope.

Rope clips attached with U-bolts shall have the U-bolts on the dead or short end of the rope. Spacing and number of all types of clips shall be in accordance with the clip manufacturer"s recommendation. Clips shall be drop-forged steel in all sizes manufactured commercially. When a newly installed rope has been in operation for an hour, all nuts on the clip bolts shall be retightened.

Wherever exposed to temperatures, at which fiber cores would be damaged, rope having an independent wirerope or wire-strand core, or other temperature-damage resistant core shall be used.

Replacement rope shall be the same size, grade, and construction as the original rope furnished by the crane manufacturer, unless otherwise recommended by a wire rope manufacturer due to actual working condition requirements.

Konecranes wire rope inspections can help crane users extend the life of hoist ropes. Ropes, sheaves and other reeving system components are inspected for compliance with crane standards, and to determine if they have flaws that could hinder safe operation. Contact us today to schedule an assessment.

In stricter senses, the term wire rope refers to a diameter larger than 9.5 mm (3⁄8 in), with smaller gauges designated cable or cords.wrought iron wires were used, but today steel is the main material used for wire ropes.

Historically, wire rope evolved from wrought iron chains, which had a record of mechanical failure. While flaws in chain links or solid steel bars can lead to catastrophic failure, flaws in the wires making up a steel cable are less critical as the other wires easily take up the load. While friction between the individual wires and strands causes wear over the life of the rope, it also helps to compensate for minor failures in the short run.

Wire ropes were developed starting with mining hoist applications in the 1830s. Wire ropes are used dynamically for lifting and hoisting in cranes and elevators, and for transmission of mechanical power. Wire rope is also used to transmit force in mechanisms, such as a Bowden cable or the control surfaces of an airplane connected to levers and pedals in the cockpit. Only aircraft cables have WSC (wire strand core). Also, aircraft cables are available in smaller diameters than wire rope. For example, aircraft cables are available in 1.2 mm (3⁄64 in) diameter while most wire ropes begin at a 6.4 mm (1⁄4 in) diameter.suspension bridges or as guy wires to support towers. An aerial tramway relies on wire rope to support and move cargo overhead.

Modern wire rope was invented by the German mining engineer Wilhelm Albert in the years between 1831 and 1834 for use in mining in the Harz Mountains in Clausthal, Lower Saxony, Germany.chains, such as had been used before.

Wilhelm Albert"s first ropes consisted of three strands consisting of four wires each. In 1840, Scotsman Robert Stirling Newall improved the process further.John A. Roebling, starting in 1841suspension bridge building. Roebling introduced a number of innovations in the design, materials and manufacture of wire rope. Ever with an ear to technology developments in mining and railroading, Josiah White and Erskine Hazard, principal ownersLehigh Coal & Navigation Company (LC&N Co.) — as they had with the first blast furnaces in the Lehigh Valley — built a Wire Rope factory in Mauch Chunk,Pennsylvania in 1848, which provided lift cables for the Ashley Planes project, then the back track planes of the Summit Hill & Mauch Chunk Railroad, improving its attractiveness as a premier tourism destination, and vastly improving the throughput of the coal capacity since return of cars dropped from nearly four hours to less than 20 minutes. The decades were witness to a burgeoning increase in deep shaft mining in both Europe and North America as surface mineral deposits were exhausted and miners had to chase layers along inclined layers. The era was early in railroad development and steam engines lacked sufficient tractive effort to climb steep slopes, so incline plane railways were common. This pushed development of cable hoists rapidly in the United States as surface deposits in the Anthracite Coal Region north and south dove deeper every year, and even the rich deposits in the Panther Creek Valley required LC&N Co. to drive their first shafts into lower slopes beginning Lansford and its Schuylkill County twin-town Coaldale.

The German engineering firm of Adolf Bleichert & Co. was founded in 1874 and began to build bicable aerial tramways for mining in the Ruhr Valley. With important patents, and dozens of working systems in Europe, Bleichert dominated the global industry, later licensing its designs and manufacturing techniques to Trenton Iron Works, New Jersey, USA which built systems across America. Adolf Bleichert & Co. went on to build hundreds of aerial tramways around the world: from Alaska to Argentina, Australia and Spitsbergen. The Bleichert company also built hundreds of aerial tramways for both the Imperial German Army and the Wehrmacht.

In the last half of the 19th century, wire rope systems were used as a means of transmitting mechanical powercable cars. Wire rope systems cost one-tenth as much and had lower friction losses than line shafts. Because of these advantages, wire rope systems were used to transmit power for a distance of a few miles or kilometers.

Steel wires for wire ropes are normally made of non-alloy carbon steel with a carbon content of 0.4 to 0.95%. The very high strength of the rope wires enables wire ropes to support large tensile forces and to run over sheaves with relatively small diameters.

In the mostly used parallel lay strands, the lay length of all the wire layers is equal and the wires of any two superimposed layers are parallel, resulting in linear contact. The wire of the outer layer is supported by two wires of the inner layer. These wires are neighbors along the whole length of the strand. Parallel lay strands are made in one operation. The endurance of wire ropes with this kind of strand is always much greater than of those (seldom used) with cross lay strands. Parallel lay strands with two wire layers have the construction Filler, Seale or Warrington.

In principle, spiral ropes are round strands as they have an assembly of layers of wires laid helically over a centre with at least one layer of wires being laid in the opposite direction to that of the outer layer. Spiral ropes can be dimensioned in such a way that they are non-rotating which means that under tension the rope torque is nearly zero. The open spiral rope consists only of round wires. The half-locked coil rope and the full-locked coil rope always have a centre made of round wires. The locked coil ropes have one or more outer layers of profile wires. They have the advantage that their construction prevents the penetration of dirt and water to a greater extent and it also protects them from loss of lubricant. In addition, they have one further very important advantage as the ends of a broken outer wire cannot leave the rope if it has the proper dimensions.

Stranded ropes are an assembly of several strands laid helically in one or more layers around a core. This core can be one of three types. The first is a fiber core, made up of synthetic material or natural fibers like sisal. Synthetic fibers are stronger and more uniform but cannot absorb much lubricant. Natural fibers can absorb up to 15% of their weight in lubricant and so protect the inner wires much better from corrosion than synthetic fibers do. Fiber cores are the most flexible and elastic, but have the downside of getting crushed easily. The second type, wire strand core, is made up of one additional strand of wire, and is typically used for suspension. The third type is independent wire rope core (IWRC), which is the most durable in all types of environments.ordinary lay rope if the lay direction of the wires in the outer strands is in the opposite direction to the lay of the outer strands themselves. If both the wires in the outer strands and the outer strands themselves have the same lay direction, the rope is called a lang lay rope (from Dutch langslag contrary to kruisslag,Regular lay means the individual wires were wrapped around the centers in one direction and the strands were wrapped around the core in the opposite direction.

Multi-strand ropes are all more or less resistant to rotation and have at least two layers of strands laid helically around a centre. The direction of the outer strands is opposite to that of the underlying strand layers. Ropes with three strand layers can be nearly non-rotating. Ropes with two strand layers are mostly only low-rotating.

Stationary ropes, stay ropes (spiral ropes, mostly full-locked) have to carry tensile forces and are therefore mainly loaded by static and fluctuating tensile stresses. Ropes used for suspension are often called cables.

Track ropes (full locked ropes) have to act as rails for the rollers of cabins or other loads in aerial ropeways and cable cranes. In contrast to running ropes, track ropes do not take on the curvature of the rollers. Under the roller force, a so-called free bending radius of the rope occurs. This radius increases (and the bending stresses decrease) with the tensile force and decreases with the roller force.

Wire rope slings (stranded ropes) are used to harness various kinds of goods. These slings are stressed by the tensile forces but first of all by bending stresses when bent over the more or less sharp edges of the goods.

Technical regulations apply to the design of rope drives for cranes, elevators, rope ways and mining installations. Factors that are considered in design include:

Donandt force (yielding tensile force for a given bending diameter ratio D/d) - strict limit. The nominal rope tensile force S must be smaller than the Donandt force SD1.

The wire ropes are stressed by fluctuating forces, by wear, by corrosion and in seldom cases by extreme forces. The rope life is finite and the safety is only ensured by inspection for the detection of wire breaks on a reference rope length, of cross-section loss, as well as other failures so that the wire rope can be replaced before a dangerous situation occurs. Installations should be designed to facilitate the inspection of the wire ropes.

Lifting installations for passenger transportation require that a combination of several methods should be used to prevent a car from plunging downwards. Elevators must have redundant bearing ropes and a safety gear. Ropeways and mine hoistings must be permanently supervised by a responsible manager and the rope must be inspected by a magnetic method capable of detecting inner wire breaks.

The end of a wire rope tends to fray readily, and cannot be easily connected to plant and equipment. There are different ways of securing the ends of wire ropes to prevent fraying. The common and useful type of end fitting for a wire rope is to turn the end back to form a loop. The loose end is then fixed back on the wire rope. Termination efficiencies vary from about 70% for a Flemish eye alone; to nearly 90% for a Flemish eye and splice; to 100% for potted ends and swagings.

When the wire rope is terminated with a loop, there is a risk that it will bend too tightly, especially when the loop is connected to a device that concentrates the load on a relatively small area. A thimble can be installed inside the loop to preserve the natural shape of the loop, and protect the cable from pinching and abrading on the inside of the loop. The use of thimbles in loops is industry best practice. The thimble prevents the load from coming into direct contact with the wires.

A wire rope clip, sometimes called a clamp, is used to fix the loose end of the loop back to the wire rope. It usually consists of a U-bolt, a forged saddle, and two nuts. The two layers of wire rope are placed in the U-bolt. The saddle is then fitted to the bolt over the ropes (the saddle includes two holes to fit to the U-bolt). The nuts secure the arrangement in place. Two or more clips are usually used to terminate a wire rope depending on the diameter. As many as eight may be needed for a 2 in (50.8 mm) diameter rope.

The mnemonic "never saddle a dead horse" means that when installing clips, the saddle portion of the assembly is placed on the load-bearing or "live" side, not on the non-load-bearing or "dead" side of the cable. This is to protect the live or stress-bearing end of the rope against crushing and abuse. The flat bearing seat and extended prongs of the body are designed to protect the rope and are always placed against the live end.

An eye splice may be used to terminate the loose end of a wire rope when forming a loop. The strands of the end of a wire rope are unwound a certain distance, then bent around so that the end of the unwrapped length forms an eye. The unwrapped strands are then plaited back into the wire rope, forming the loop, or an eye, called an eye splice.

A Flemish eye, or Dutch Splice, involves unwrapping three strands (the strands need to be next to each other, not alternates) of the wire and keeping them off to one side. The remaining strands are bent around, until the end of the wire meets the "V" where the unwrapping finished, to form the eye. The strands kept to one side are now re-wrapped by wrapping from the end of the wire back to the "V" of the eye. These strands are effectively rewrapped along the wire in the opposite direction to their original lay. When this type of rope splice is used specifically on wire rope, it is called a "Molly Hogan", and, by some, a "Dutch" eye instead of a "Flemish" eye.

Swaging is a method of wire rope termination that refers to the installation technique. The purpose of swaging wire rope fittings is to connect two wire rope ends together, or to otherwise terminate one end of wire rope to something else. A mechanical or hydraulic swager is used to compress and deform the fitting, creating a permanent connection. Threaded studs, ferrules, sockets, and sleeves are examples of different swaged terminations.

A wedge socket termination is useful when the fitting needs to be replaced frequently. For example, if the end of a wire rope is in a high-wear region, the rope may be periodically trimmed, requiring the termination hardware to be removed and reapplied. An example of this is on the ends of the drag ropes on a dragline. The end loop of the wire rope enters a tapered opening in the socket, wrapped around a separate component called the wedge. The arrangement is knocked in place, and load gradually eased onto the rope. As the load increases on the wire rope, the wedge become more secure, gripping the rope tighter.

Poured sockets are used to make a high strength, permanent termination; they are created by inserting the wire rope into the narrow end of a conical cavity which is oriented in-line with the intended direction of strain. The individual wires are splayed out inside the cone or "capel", and the cone is then filled with molten lead-antimony-tin (Pb80Sb15Sn5) solder or "white metal capping",zincpolyester resin compound.

Donald Sayenga. "Modern History of Wire Rope". History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy (atlantic-cable.com). Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

8613371530291

8613371530291