wire rope failure modes free sample

A failure analysis of a broken multi strand 71mm steel wire rope used in the main towing winch was carried out. The wire rope was failed during a bollard pull test. The wire rope was a new one and had failed during the first use. The wire rope was in IWRC/ RHO 6X41 constructions. Fig.1 shows the typical cross section of the wire rope. The failure investigation is performed by chemical and metallurgical examinations.

(ii) the uniformity and cleanliness of the microstructure of the rope steel and the effect of microstructure on crack initiation and propagation, and

1) Chemical analysis of steel wire rope is presented in Table 1. The analysis showed that it is made of high carbon steel corresponding to AISI 1074 grade, and galvanized with zinc to resist corrosion.

2) The microstructure observed under optical microscope and is shown in Figs. 2. It was typical of a drawn ferrite–pearlitic steel wire with heavily cold worked micro structure. Further examination of microstructure of the failed wires did not indicate any sign of metallurgical problems such as de- carburized layer, nonmetallic inclusions, or martensite formation. In addition, the wires were free from any sort of corrosion and pitting. Therefore, corrosion had no role in the failure of wires.

4) Table 3 represents the tensile values of the wire. The result indicates relatively less value comparing the metallographic results and the mill test certificate supplied by the Client. Figs. 3 showing Stress- Strain during tensile testing of the wire

The high hardness values, chemical composition, and the pearlitic structure of wires indicating that this is a type of extra extra improved plow steel (EEIPS) grade wire ropes. These types of wires have typically higher load-bearing capacity as compared with other grades. They are considered as heavy-duty wire ropes. The minimum tensile strength of EEIPS is 2160 N/mm2. (Ref. API Spec 9A)

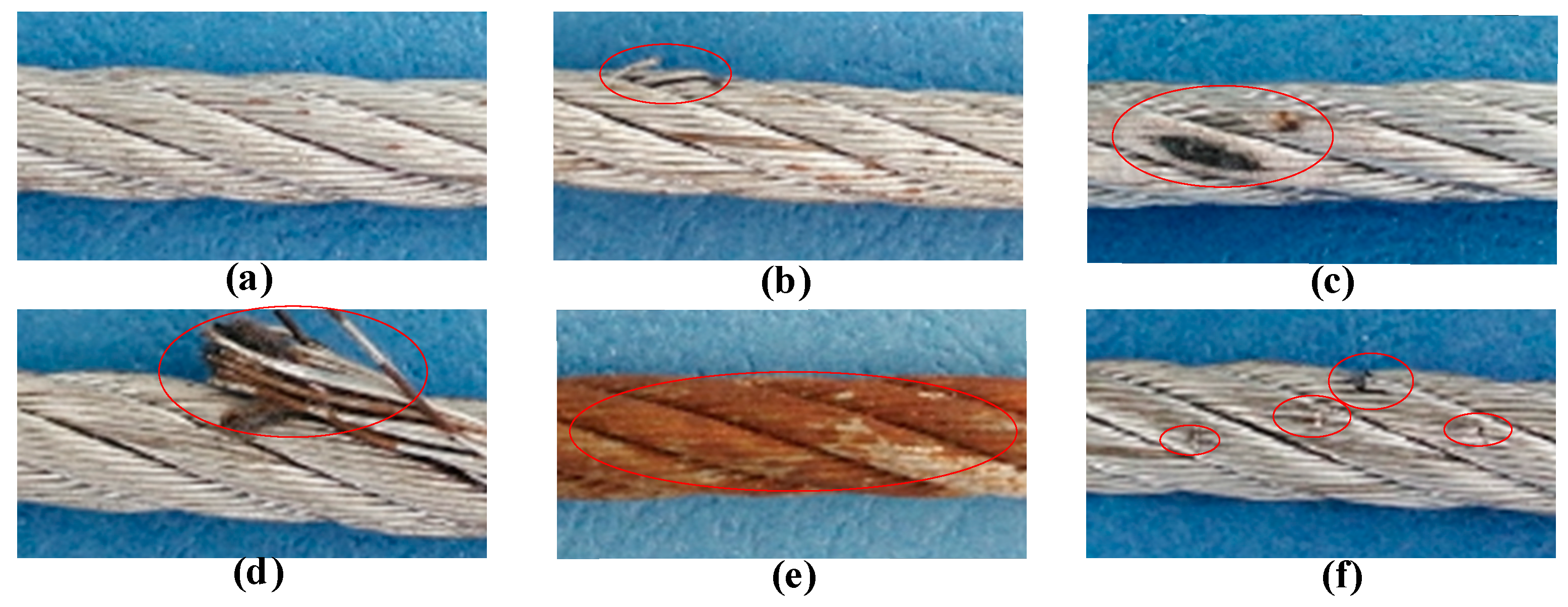

5) The fractured ends of group of wires were visually inspected. Majority of wires failed in shear, and the remaining had cup-and-cone fracture, some of which are shown in Fig. 4.

Fractographs of broken wires in the form of cup and cone and shear are shown in Fig. 5 and Fig.6. Tensile overload fracture occurs when the axial load exceeds the breaking strength of the wires. This type of fracture usually appears in ductile manner, either in the form of cup and cone or in shear mode. In the former case, there is a reduction at the fracture which is called necking, whereas in the case of the latter, fracture surface is inclined at 45degree to the wire axis. In both cases, ductile dimple formations are clearly observed and confirm the tensile overloading of wires.

Every wire rope failure will be accompanied by a certain number of tensile over load breaks. The fact that tensile overload wire breaks can be found therefore necessarily mean that the rope failed because of an overload. The rope might have been weakened by fatigue breaks. The remaining wires were then no longer able to support the load, leading to tensile overload failures of these remaining wires.

Only if the metallic area of the tensile overload breaks and shear breaks combined is much higher than 50% of the wire rope’s metallic cross section is it likely that the rope failed because of an overload.

Shear breaks are caused by axial loads combined with perpendicular compression of the wire. Their break surface is inclined at about 45degree to the wire axis. The wire will fail in shear at a lower axial load than the pure tensile over load.

If a steel wire rope breaks as a consequence of jumping a layer or being wedged in, a majority of wires will exhibit the typical 45degree break surface.

In the instant case the wire rope was failed at 100 Ton or even less. As the breaking load of the wire rope is 353 Tons, there is no reason for a tensile over load breaks in an axial direction and that too considering the fact that the wire rope was failed during a bollard pull test. Fig. 7 shows the maximum stress generations in the wire rope at 100 Ton under normal bollard pull test. More over the metallurgical investigation is also not suggesting for any factors that fostering an axial overload failure.

The failure of the wire rope was studied in detail. In order to investigate the problem metallurgical and mechanical post failure analyses were performed. The wire rope was made of AISI 1074 grade steel, and it was a type of EEIPS. The microstructure was composed of severely deformed and elongated ferrite–pearlite, and no other phase formation or nonmetallic inclusions could be detected. The morphologies of fractured surfaces indicated that the wires were mainly failed in shear mode and few in tensile mode. Owing to galvanized coating, the wires were free from corrosion.

The tensile strength of the wire material is less than the required value. The required tensile strength of EEIPS is 2160 N/mm2 and the obtained value is 2059 N/mm2. But this factor is not a reason for the current failure of the wire rope. The said point is substantiated by the following:

It is concluded that the wire rope was failed due to shear breaks. Shear breaks were caused by high axial loads combined with perpendicular compression of the wire. It is worthwhile to note that the rope was failed in its first usage. The shear break is linked to the lapses during the installation/ spooling of the wire rope.

b) Lack of pretension of lower rope layers during spooling. In the absence of proper pretension the upper layers might be pulled in between the lower layers during loading.

c) Under high tension, the rope tends to be as round as possible. With no load, a rope can be deformed and flattened much easily. Highly tensioned upper layers will therefore severely damage loose (and therefore vulnerable) lower layers.

Unfortunately, many phone calls into ITI Field Services begins this way, “We have had an incident with a wire rope and we believe the rope failed. How do we determine the cause of failure?”

Fortunately, the calls come in because wire rope users want to determine cause of failure in an effort to improve their crane, rigging and lifting activities.

A wire rope distributor received a hoist rope and sockets from a rubber-tired gantry. The rope and sockets were returned by the customer who believed the rope and sockets failed. The distributor hired ITI Field Services to conduct an analysis on the rope and sockets to determine the cause of the failure and to produce written documentation.

Based on the findings of the examination, fatigue-type breaks in the wires indicated that the wire rope lost significant strength due to vibration. There was no indication that the rope was overloaded. The poured sockets showed no evidence of abnormalities in the pouring method, wire zinc bonding length or the materials used in the speltering process. The conclusion of the inspection is that rope failed due to fatigue.

Wire rope examination is just one of the many services that is offered by ITI Field Services. ITI has some of the most highly-regarded subject-matter experts in the crane and rigging industry with experience in performance evaluations, litigation, accident investigations, manual development and critical lift planning reviews.

This article focuses on the mechanisms and common causes of failure of metal components in lifting equipment in the following three categories: cranes and bridges, particularly those for outdoor and other low-temperature service; attachments used for direct lifting, such as hooks, chains, wire rope, slings, beams, bales, and trunnions; and built-in members such as shafts, gears, and drums.

8613371530291

8613371530291